ICT-Supported Design Thinking Workshop Program: A Case Study of

Encouraging Social Lean-In for High School Students in Japan

Dunya Donna Chen, Jiayi Lu and Keiko Okawa

Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University, Yokohama, Japan

Keywords:

Constructionism, Nonformal Learning, ICT, Design Thinking Process, Social Lean-In.

Abstract:

Since 2015, an ICT-supported workshop program based on the constructionism approach has been imple-

mented at Fujimikaoga High School for Girls (FHS) in Japan. Keio University Graduate School of Media

Design students from diverse cultural backgrounds facilitates the nonformal learning experience. The pro-

gram employs a design thinking process (DTP) and ICT tools to enhance active collaborative learning and

intercultural interactions. Over 800 students have participated, demonstrating gains in critical thinking, in-

vestigation, feedback articulation, and iteration of their own views. This paper details the program’s concept,

process, qualitative findings, key elements of success, and challenges during implementation.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Contextual Progression

The notion of globalization is often discussed with re-

spect to its commercial, cultural, and societal aspects

(Ritzer and Dean, 2019). The progression in tech-

nological infrastructure amplified the overall smart-

phone adoption rate in Japan (Tateno et al., 2019).

This affluence in accessibility has facilitated more op-

portunities for interpersonal communication and ex-

posure to diverse cultures. Specifically, the social fea-

tures on platforms enable these connections, allowing

youngsters today to participate actively (Lehdonvirta

and R

¨

as

¨

anen, 2011).

While youngsters engage digitally, they may in-

evitably encounter discussions about worldwide mat-

ters and challenges, ones in Japan included (Lehdon-

virta and R

¨

as

¨

anen, 2011). Online and offline interac-

tions necessitate cultural sensitivity, competence, and

respectful communication (Parkinson, 2009; Cush-

ner, 2015; Nastasi, 2017).

To develop these crucial skills, the Programme

of International Student Assessment (PISA) recom-

mends promoting global competence through the cul-

tivation of critical thinking and intercultural appreci-

ation in discussing, analyzing, and taking action to-

ward global subjects (OECD, 2018). Such skills are

crucial for constructing a harmonious multicultural

community in the long run (OECD, 2018; Tichnor-

Wagner and Manise, 2019). Various initiatives world-

wide aimed at promoting global competence among

high school students exist (Tsang et al., 2020), al-

though, in Asia, they typically take the form of short-

term competitions rather than long-term program in-

tegration in support of the school curriculum.

1.2 Use of ICT: Pre and During

COVID-19

In 2022, a study found that prior to the COVID-

19 pandemic, Information and Communication Tech-

nologies (ICT) use in secondary school classrooms

in Japan varied across the country (Iwabuchi et al.,

2022). The hesitation in using ICT tools in Japan’s

classrooms was also reflected in the findings from a

2013 study, as well as the country’s low ranking in

the OECD’s report, which indicates a reliance on tra-

ditional methods of instruction (OECD, 2020; Kusano

et al., 2013). During this period, ICT was largely per-

ceived as a stand-alone subject with limited integra-

tion into the overall education process.

During COVID-19, educators in Japan had to ex-

ploit assorted digital services obtainable to continue

teaching (Kang, 2021), resulting in increased ICT tool

adoption among both educators and learners (Kang,

2021). However, ICT primarily served as a means of

communication during this period in Japan, replacing

physical presence (Kang, 2021). E-mail and Zoom

were frequently used alternatives for communication

between teachers and students, but the formal educa-

Chen, D., Lu, J. and Okawa, K.

ICT-Supported Design Thinking Workshop Program: A Case Study of Encouraging Social Lean-In for High School Students in Japan.

DOI: 10.5220/0011969300003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 2, pages 527-534

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

527

tion approach remained unchanged (Barry and Kane-

matsu, 2020; Kuromiya et al., 2022). Interestingly,

studies suggest that teachers and parents in Japan still

favor physical learning environments rather than in-

tegrating digital tools into their practice (Akabayashi

et al., 2023; Ikeda, 2022).

1.3 Motivation

The progress of technology and ease of information

access has enabled learning to evolve beyond tradi-

tional physical settings. These context conditions led

to the creation of a proposed program that aims to ex-

plore the viability of a structured nonformal tutorial

environment to foster peer learning while studying the

influence of ICT tools on students’ relationships, mo-

tivation to learn, and knowledge acquisition.

1.4 Structure of Discussion

To provide clear visibility of the process for the pro-

gram, the following discussion will be divided into

three main parts: 1) Section 2 primarily discusses the

overall foundation of the program. 2) Section 3 con-

centrates on the deliberate use of the Design Thinking

Process for implementation. 3) Section 4 discusses

using ICT tools to enable peer learning and intercul-

tural, multicultural, and cross-team interactions.

2 PROGRAM FOUNDATION

2.1 Aims and Structure

Formal learning is demarcated as obligatory with the

aim of attaining accreditation, vastly composed by

the lecturer under an educational establishment within

the scheme (Eshach, 2007; Cedefop, 2014). Specif-

ically, Japan’s secondary education addressing stu-

dents’ needs for global competence is primarily mo-

tivated by schooling in a formal education approach

(Davidson and Liu, 2020). Under this method, topics

were often taught in textbook-directed methods and

concluded as the lecture was completed, as the con-

tent was delivered and expectantly obtained by the

students.

Conversely, nonformal learning is typically run

by a chaperon, systematically prearranged in accor-

dance with learning objectives, and participants at-

tend voluntarily, deprived of assessments, nor ob-

tainment of accreditation (Hamadache, 1991). Stud-

ies suggest that nonformal learning practices enable

students to gain problem-solving skills, build self-

confidence through reflecting on experiences, and

proactively seek knowledge (Dib, 1988). The nonfor-

mal learning in this program is defined by the OECD

as learning through a program that does not involve

evaluation or certification (OECD, 2005).

Arguably, learning can arise in various settings

through diverse methodologies when new informa-

tion is presented and connected to existing knowledge

schemes (Saunders and Wong, 2020). The proposed

program aims to provide supplementary scaffolding

for student-centered learning experiences in a non-

formal setting, promoting active reflection, creativity,

and meaning-making through experiences. As illus-

trated in Figure 1, the proposed structure does not aim

to modify the current formal approach in Japan’s sec-

ondary education, but rather to enable students to de-

velop global competence skills through offline experi-

ences and broaden their contact with diverse cultures

through ICT tools.

Figure 1: Proposed Structure of the Program.

2.2 Nonformal Learning

Constructionism is based on the idea that individuals

learn best when actively constructing understanding

and meaning, rather than passively receiving informa-

tion (Harel and Papert, 1991). Rather than committal

to memorization, Figure 2 illustrates the supporting

theories used in the proposed program.

Figure 2: Supporting Theories for the Proposed Program.

The program is partly constructed based on

Lev Vygotsky’s concept of constructing knowledge

through socialization (Vygotsky and Cole, 2018;

Pass, 2004). Facilitators, local community members,

high school teachers, and student peers all play a role

in the communication and learning process. Through

social interaction, students create their own interpre-

tations of the material and integrate them with exist-

ing schemas (Gallagher and Reid, 2002).

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

528

Incorporating a social constructivist learning the-

ory in the proposed program has numerous benefits,

including the ability for students to identify areas of

interest, foster creativity, and collaborate with peers to

appreciate diverse perspectives (Vygotsky and Cole,

2018). This approach also inspires active reflection

and discovery, enhancing the creation of knowledge

(Alam, 2022; Ali, 2019). Moreover, the social con-

structivist method provides workshop facilitators with

a degree of autonomy, allowing them to tailor the ses-

sions to the needs and level of understanding of dif-

ferent participants (Vygotsky and Cole, 2018).

Jean Piaget’s learning theory of constructivism

supports the second half of the grounding philosophy

for the proposed program (Pass, 2004). Reflecting on

one’s own practices is a critical aspect of adapting and

integrating new information (Pass, 2004). This re-

flection procedure encourages exploration and active

learning (Gallagher and Reid, 2002).

2.3 Creating the Environment

The proposed program intends to foster students’ so-

cial lean-in and promote global competence devel-

opment by creating a learning environment that in-

tegrates social context with exposure to global is-

sues. This approach aligns with the idea that global

competence is often enhanced within a social context

through proactive engagement with real-world global

issues (OECD, 2018).

To motivate social lean-in, the program has been

designed to shift students from passive knowledge

receivers to active learners and enhance their global

competence through nonformal learning opportuni-

ties. It utilizes the Design Thinking Process (DTP)

(Friis Dam and Yu Siang, 2020) to facilitate students’

awareness of a specific topic of interest, apprecia-

tion of diverse perspectives, and proactive problem-

solving (Rao et al., 2022) As 21st-century students

are naturally inclined to be technology-savvy, digital

resources have become an intuitive form of learning

outside of school (Saykili, 2019). Incorporating ICT

tools in the program, therefore, provides an efficient

way to transmit, store, create, share, and exchange in-

formation and ideas (Saykili, 2019).

3 IMPLEMENT VIA DTP

The study focuses on exploring the potential of utiliz-

ing the nonformal learning environment and dynamic

interaction between ICT tools and DTP framework

for promoting the acquisition of global competence

and social lean-in among students.

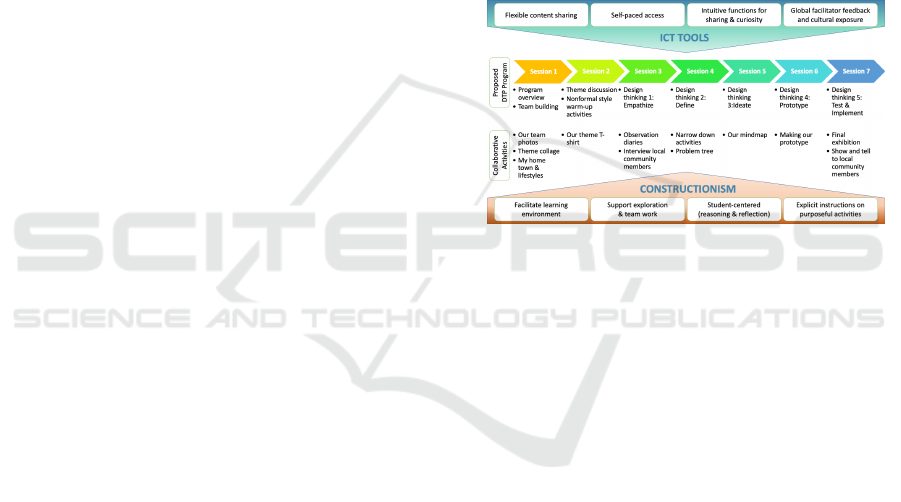

Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 3, the pro-

gram is grounded on constructionism values and aims

to provide a nonformal learning setting that utilizes

ICT to support global competence development. De-

sign thinking practices are employed as a guide to en-

able students to actively perceive, discover, and ana-

lyze their local communities. The ICT tools’ innate

characteristics brought a many-to-many communica-

tion platform that further supports the construction of

peer learning (Pfister, 2011). Collaborative learning,

which is an operative means to benefit the learning

progression and increase the learning involvement for

learners (Topping, 2005), is possible under the peer

learning theory. Through this setting, students can es-

tablish connections with local community members

and actively interact with the facilitator community.

Figure 3: Relationships among the Proposed Program, Con-

structionism, and ICT Tools.

In addition, Self-Determination Theory supports

using a continuum and interactive structure to fulfill

the inner needs for competence, connection, and au-

tonomy, as well as social interpersonal communica-

tion, all of which can enhance knowledge construc-

tion and motivation to learn (Flannery, 2017; Parr

and Townsend, 2002). The proposed program takes

this into account by providing room for individual

decision-making and ownership while utilizing ICT

tools for cooperative learning and peer assessment

(Jacobs and Ivone, 2020; Pinheiro and Sim

˜

oes, 2012).

These aspects further enhance student engagement

and broaden their perspectives as they share their dis-

coveries.

3.1 Collaboration with Fujimigaoka

High School (FHS)

Since 2015, the proposed program has been annually

implemented outside of regular class hours at FHS, an

all-girls secondary education institution in Japan that

aims to “nurture young ladies with a global mindset”

(FHS, 2015). The proposed program, which has an

average of 100 tenth-grade participants each year, is

incorporated into the compulsory course “Basic Sus-

ICT-Supported Design Thinking Workshop Program: A Case Study of Encouraging Social Lean-In for High School Students in Japan

529

tainability”, as part of FHS’s designation as a “Su-

per Global High School” (FHS, 2015) by the Japanese

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and

Technology.

Facilitated by the Global Education project team

at Keio University Graduate School of Media Design,

the program features an average of 1 to 1.7 facilitator-

to-group ratio, allowing for more thorough discus-

sions and improved relational connections between

students and facilitators. The project team com-

prises postgraduate students from at least 15 countries

across Asia, Europe, North America, South America,

and the Middle East, offering high school students the

opportunity to interact with facilitators from diverse

cultural backgrounds.

3.2 Frequency of Implementation

The proposed ICT-supported workshop program was

conducted at FHS in Japan, typically once a month

from June to January of the following year. The in-

tervals between workshops allowed students to gain

practical experience through hands-on learning in the

field.

3.3 Specifics of the Proposed Program

The workshop comprises eight sessions that use DTP

as a framework for facilitation. The first two ses-

sions aim to orient students to the program and project

theme while fostering group bonding. The remain-

ing six sessions guide students to explore, examine,

ideate, and create solutions for a community of their

choice, based on project themes such as global econ-

omy, sustainable development, climate action, and

gender equality. The following discussion will focus

on the third session and beyond, where DTP is uti-

lized.

3.3.1 Design with Culture in Mind

FHS students, who have not previously participated

in non-formal learning, may initially expect detailed,

step-by-step instructions from the facilitators. To

challenge this mindset and facilitate the transition to

non-formal learning, the program’s third and fourth

session focuses on DTP’s “empathize and define”

stage.

3.3.2 DTP Phase 1: Empathize and Define

The “empathize and define” phase comprises two

workshop sessions that aim to raise students’ aware-

ness of their community through practical experi-

ences such as keeping an observation diary, conduct-

ing interviews, and reflecting on community issues

and situations. Figure 3 illustrates 4 main activities

designed for team members to interact with each other

and international facilitators, providing opportunities

to apply their learning even beyond the workshop ses-

sions.

In 2016, the proposed program built upon the for-

mal classroom learning of the global economy by

providing students with practical experiences in field

research and observation, data collection, and pro-

cess analysis related to locally-made goods for the

global market. This hands-on approach encouraged

active exploration and critical thinking, moving stu-

dents away from traditional passive learning methods.

By utilizing the discovery learning concept, the pro-

gram attempts to develop self-sufficient learners who

determine the linkage among diverse evidence, per-

ceptions, and theories rather than relying on straight-

forward teaching (Clark, 2018).

3.3.3 DTP Phase 2: Ideate and Feedback

This phase, depicted in Figure 3, consists of two

workshop sessions with main activities that aim to

unify information obtained from previous sessions,

establish arguments, articulate individual sentiments,

and stimulate deliberations toward common goals.

The implementation of this phase has shown that

culture is a crucial factor influencing student partici-

pation. The local culture of valuing conformity, social

expectations of obedience, and females being agree-

able can act as barriers to learning. Therefore, the

proposal was modified to address these cultural char-

acteristics, challenging students’ comfort zone by re-

quiring them to articulate criticism with reasoning and

express individual views. Often, tutors tend to simply

encourage students to speak up, but the proposed pro-

gram goes further by creating a safe environment for

sharing and conversing. Observations indicate facili-

tators’ determination to generate such an environment

is a significant first step.

The mindmap technique was used during the ses-

sions to ideate solutions and understand the intercon-

nection of stakeholders and its multifaceted nature

in a topic. Facilitators mediate and encourage pro-

ductive exchanges among peers and constructive re-

flection. Post-session, students refine their ideation

based on peer feedback, which would gain practice

in problem-solving, decision-making, and communi-

cation, providing experiences that are not typically

found in traditional formal schooling.

Such problem-based and case-based learning per-

mit students to practice their knowledge in real-life

circumstances, encouraging advanced cognition ca-

pacity (PCTL, 2021; CITL, 2021). This exercise

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

530

in striving under challenging situations facilitates a

growth mindset (Dweck, 2016), and community inter-

action enables students to expand their understanding

of self-identity and personal values.

3.3.4 DTP Phase 3: Prototype and Testing

Aligned with global competence thinking, the final

phase of the program encourages students to take ac-

tion and showcase their creations through a year-end

exhibition. Preparing and exhibiting the work allows

students to take ownership. Building upon the expe-

rience in phase 2, the final exhibition challenges stu-

dents to interact among team members and consider

and construct the meaning of their proposed solutions.

Here the area of learning comes from considering the

impact of proposed solutions for the target commu-

nity.

During this phase, facilitators focus on ensuring

the freedom of exploration in prototyping and learn-

ing through trial and error whilst maintaining motiva-

tion. The reflection on experiences enables students

to gain awareness of the total experience. Based on

the feedback from students, it is noticeable that this

final process also enables students to gain a sense

of control and confidence as well as bonding among

the members. According to McClelland’s theory of

needs (Osemeke and Adegboyega, 2017), this oppor-

tunity to demonstrate competence satisfies the need

for achievement and becomes one of the motivators

which further ignites students’ learning behavior.

4 ICT’s CONTRIBUTION

ICT tools are selected for their ability to transmit,

store, share, and exchange information, thoughts, and

communication, supporting the collaborative learning

process (Pinto and Leite, 2020). Additionally, using

ICT allows students to learn at their own pace. The

discussion below is structured around the three pri-

mary contributions of ICT tools. The specific func-

tions, values, and observations for the use of ICT in

the proposed program are summarized in Table 1.

4.1 Co-Creation Within Team

Observations from the implemented sessions show

that ICT tools such as Google Slides, Jamboard,

Padlet, Miro, and Zoom supported group work and

co-creation processes within each team. These tools

were chosen to shift students’ attention from large

group peer pressure and conformity culture, providing

each team with a secluded platform that helps them

stay focused on small group discussions while having

enough flexibility to share information among mem-

bers. Online ICT tools provide options for learning

pace and communication in preferred formats.

Feedback received from students indicates that

they appreciated the interactions among team mem-

bers, particularly for data analysis and logic flow or-

ganization to create their project proposal. Students

also noticed the flexibility of ICT platforms, and their

ease of use supported them in proactively exploring

other functions during the co-creation process, pro-

viding them with a sense of autonomy. Observations

of student behavior during sessions show that they

were more willing to take the initiative to communi-

cate without probing from facilitators.

4.2 Large-Scale Discussion

Given the large number of participants each year,

challenges related to visibility on the progress of in-

dividual groups and large-scale participant discus-

sion were anticipated. To address these challenges,

tools such as Mentimeter, Padlet, and Miro were em-

ployed. Data confirmed that these tools enabled stu-

dents to have wider visibility into the work of their

peers upon initial completion of work within each

team, which further stimulates their interest in other

groups’ progress and discussion among and within

their team members. Increased cross-team interac-

tions were also observed, as well as the ability to

discuss, appreciate, comment, and share the work

of other teams within their own group. From the

perspective of Self-Determination Theory (Flannery,

2017), the nonformal learning setting and ICT tools

offer fertile ground for autonomy. The exhibition

at the end of the program offers an opportunity to

demonstrate students’ competence, and peer social in-

teractions throughout the program contribute towards

the relatedness. By fulfilling the need for autonomy,

competence, and relatedness, the proposed program

helps foster students’ intrinsic motivation to learn.

4.3 Intercultural Interactions

In addition to cross-team interactions, the mediation

of ICT tools was particularly pronounced when travel

was limited due to COVID-19. Facilitators were sit-

uated around the globe in their home counties while

participants were in Japan. Zoom enabled commu-

nication to be established in various formats regard-

less of geographical boundaries. For example, in DTP

phase one, Zoom’s live audio-visual images allowed

both facilitators and students to share their local com-

munity environment and lifestyle. During these inter-

ICT-Supported Design Thinking Workshop Program: A Case Study of Encouraging Social Lean-In for High School Students in Japan

531

Table 1: Functions and Value of ICT Tools Used in the Proposed Program.

Tools

Functions

Tex t Tran smi ss ion Image Transmission Audi o-v is ual Transmiss io n Data Storag e Interpersonal Communication

Visi bi lity of other Gro ups'

Work

Mass Communication

Val ue Co nt ri bu tion to t he

Program

Offered commu nicati on

channel

Offered mult isen sory

stimulation

Offered mult isen sory

stimulation

Ensu red conti nu ous 2 4/7/3 65

access for self-paced learning

Encourag ed wi thin-team and

cross-team discussions

& Connected students with

facilitators worldwide

Provided opportunities for

peer learning

Allo wed i ndivi dual s to be

heard and seen by all attendees

Observ at io n Evi dences

Students actively participated

in discussions on Zoom and

Padlet

Students took

photos/screenshots of slides

and used mood boards for

projects

Students showed active

comprehension by taking

notes, nodding heads, and

asking relevant questions

Students accessed and checked

resources uploaded on Padlet

after sessions

Students collaborated on

projects using Canva, Google

Slides, and Jamboard

Students commented and

interacted with each other's

work o n Padlet and Mi ro

Students expressed individual

opinions using MentiMeter

during online sessions

Zoom √ X √ X √ X √

Canva X X X √ X X X

Padlet √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Goog le Sli des √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Miro √ √ √ √ √ √ √

MentiMeter √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Jamboard √ √ √ √ √ √ √

actions, students can non-formally become aware of

the cultural differences as facilitators visually show

and tell their physical settings and introduce local

lifestyles. Meanwhile, tools such as Mentimeter gave

students a unique experience as they voice out indi-

vidual thoughts anonymously, which was a unique ex-

perience in a collectivist and conformist cultural con-

text.

Insights from these experiences were organized

and documented using Jamboard, Padlets, and Miro,

which facilitated internal deliberation as students pro-

gressed to the second phase of the DTP process. Here,

facilitators oversaw the development of the investiga-

tion, engaged students in text conversations to reflect

on experiences, and challenged their presumptions,

thus developing their cultural metacognition (Chua

et al., 2012). This process allowed students to com-

bine newfound insights with pre-existing thinking and

creatively address community issues.

Students gain support on the content of work, en-

counter interpersonal and intercultural connections,

and problem-solving skills. With these experiences,

students learned the diversity in perspectives and how

culture shapes one’s value system and beliefs, further

influencing behavior. This new interaction, feedback,

and support experience, from a social learning pro-

cess perspective, acts as a motivator for learners to

continue to take proactive actions and overcome the

fear of failure and attempt to step out of their current

comfort zone of formal learning style.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Insights from Student Feedback

Table 2 presents qualitative responses from student

surveys that provide valuable insights into students’

learning experiences and workshop design. These

responses indicate that participants have developed

self-awareness and critical thinking abilities, become

more invested in community issues, and demonstrated

motivation to propose and take action towards ad-

dressing these issues, showcasing social lean-in. Fur-

thermore, the process of learning to ”lean in” has been

found to cultivate a growth mindset. The positive con-

versation during the program further motivated stu-

dents, who were provided with an open and safe en-

vironment to express their views, provide peer re-

sponses, and share knowledge. Facilitators could also

exchange views with students outside planned times

and restricted physical sites.

Qualitative feedback also indicated first-hand in-

volvement in this program promotes understanding

of diverse perspectives where students recognize the

importance of mental flexibility and respecting dis-

similar views when approaching and examining situa-

tions. In addition, the program provided a foundation

for a flipped classroom experience with the support

of ICT tools, offering access to educational resources

outside of workshop sessions and facilitating individ-

ualized support during the workshop sessions. As a

result, students engaged more in activities and discus-

sions during session hours and proactively explored

learning materials outside of the workshop.

5.2 Key Elements of Success

The proposed program’s implementation has revealed

several key elements of success. First is the collab-

oration and support from the high school where the

program was held. As change is a rather challenging

topic culturally (Saito, 2018), having an open-minded

institution agree to this partnership was essential for

the program’s successful implementation. The school

provided access and acted as a strong liaison with

smooth communication and commitment throughout

the years of study.

Additionally, facilitators’ dedication, extra time in

pre-session training, open discussion, and preparation

contributed significantly to the program’s success.

The open and honest sharing of experiences, both suc-

cesses and challenges, further bonds the facilitators

and allows best practices to be quickly learned and

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

532

Table 2: Students’ Learnings.

Themes Examples

Increased awareness of self within the community

“The most important thing I learned today was to think about social issues as my own.”

“I learned that it is important to find social issues starting from myself.”

Developed ability to critically evaluate information, articulate and refine own

ideas, and form well-reasoned opinions

“There were many times when I could not express my opinions, but I did my best to participate

actively. I was able to share my opinions with everyone.”

“By asking people questions, you can learn things you wouldn’t have thought of on your own.”

Greater understanding and recognition of the causes of certain community issues

“The most important thing I learned today was to think deeply about causes.”

“The problems that are happening today are caused by many different things.”

Motivation to take action toward community issues

“I would like to have the opportunity to freely express my thoughts and thoughts about our

current situation and the environment through illustrations.”

Cultivation of a growth mindset th rough th e p rocess o f learning to “lean-in” “I learned that it is important to continue to take on challenges.”

Gained broader perspectives

“I found that expressing daily problems in writing and pictures helps me to think about solutions

at the same time.”

Willingness to engag e with and learn fro m diverse perspectives

“The most important thing I learned today was to expand my inspiration by listening to different

people’s opinions.”

“Different people have different opinions on the same issue, so it is necessary to take into

account the other person’s ideas.”

Individual

Level

Interpersonal

Level

adapted to unique facilitator-student circumstances.

The qualitative feedback suggests that well-prepared

and adequately trained facilitators can adapt to diverse

learning needs, improving student learning outcomes.

Furthermore, a broad enough topic that is rele-

vant to students’ formal learning and their local con-

text also contributes to the success of implementation.

Having a wider topic allows students to explore in

a nonformal learning environment, and context rele-

vancy further motivates students to lean in.

However, challenges were encountered during the

implementation, including but not limited to aspects

such as varying levels of student engagement, limita-

tions in terms of time and resources, which had an

impact on the consistency and sustainability of the

workshop, and the struggle in time to allow students

to learn at their own pace.

Future work includes making the workshop more

relevant to current learning methods, using digital

tools, and connecting with local community members

and stakeholders. Quantitative studies across differ-

ent locations and regions will help gain a deeper un-

derstanding of the workshop’s impact.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the 800+ students and

teachers of FHS, as well as colleague facilitators, for

their support and participation in the workshop activi-

ties over the past eight years. Their contributions were

crucial to the success of the program.

REFERENCES

Akabayashi, H., Taguchi, S., and Zvedelikova, M. (2023).

Access to and demand for online school education

during the covid-19 pandemic in japan. International

Journal of Educational Development, 96:102687.

Alam, A. (2022). Mapping a sustainable future through

conceptualization of transformative learning frame-

work, education for sustainable development, critical

reflection, and responsible citizenship: an exploration

of pedagogies for twenty-first century learning. ECS

Transactions, 107(1):9827.

Ali, S. S. (2019). Problem based learning: A student-

centered approach. English language teaching,

12(5):73–78.

Barry, D. M. and Kanematsu, H. (2020). Teaching during

the covid-19 pandemic. Online Submission.

Cedefop (2014). Terminology of European education and

training policy A selection of 130 key terms. Second

edition. Cedefop Information Series. Luxembourg:

Publications Office.

Chua, R. Y., Morris, M. W., and Mor, S. (2012). Collaborat-

ing across cultures: Cultural metacognition and affect-

based trust in creative collaboration. Organizational

behavior and human decision processes, 118(2):116–

131.

CITL (2021). Problem-based learning (pbl). Accessed on:

Jan 18, 2023.

Clark, K. R. (2018). Learning theories: constructivism.

Cushner, K. (2015). The challenge of nurturing intercul-

tural competence in young people. The International

Schools Journal, 34(2):8.

Davidson, R. and Liu, Y. (2020). Reaching the world out-

side: cultural representation and perceptions of global

citizenship in japanese elementary school english text-

books. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 33(1):32–

49.

Dib, C. Z. (1988). Formal, non-formal and informal edu-

cation: concepts/applicability. In AIP conference pro-

ceedings, volume 173, pages 300–315. American In-

stitute of Physics.

Dweck, C. (2016). What having a “growth mindset” actu-

ally means. Harvard Business Review, 13(2):2–5.

Eshach, H. (2007). Bridging in-school and out-of-school

learning: formal. Non-Formal, and.

FHS (2015). Super global high school(sgh). Last accessed

6 March 2023.

Flannery, M. (2017). Self-determination theory: Intrinsic

motivation and behavioral change. In Oncology nurs-

ing f

´

orum, volume 44.

Friis Dam, R. and Yu Siang, T. (2020). Design thinking: A

quick overview.

Gallagher, J. M. and Reid, D. K. (2002). The learning the-

ory of Piaget and Inhelder. iUniverse.

Hamadache, A. (1991). Non-formal education: A defini-

tion of the concept and some examples. Prospects,

21(1):111–24.

ICT-Supported Design Thinking Workshop Program: A Case Study of Encouraging Social Lean-In for High School Students in Japan

533

Harel, I. E. and Papert, S. E. (1991). Constructionism.

Ablex Publishing.

Ikeda, O. (2022). The reality of online education by the

busiest japanese teachers in public primary and junior

high schools under covid19 in japan. In 2nd Inter-

national Conference on Social Science, Humanity and

Public Health (ICOSHIP 2021), pages 40–45. Atlantis

Press.

Iwabuchi, K., Hodama, K., Onishi, Y., Miyazaki, S., Nakae,

S., and Suzuki, K. H. (2022). Covid-19 and education

on the front lines in japan: What caused learning dis-

parities and how did the government and schools take

initiative? In Primary and Secondary Education Dur-

ing Covid-19, pages 125–151. Springer, Cham.

Jacobs, G. M. and Ivone, F. M. (2020). Infusing cooperative

learning in distance education. TESL-EJ, 24(1):n1.

Kang, B. (2021). How the covid-19 pandemic is reshap-

ing the education service. The Future of Service Post-

COVID-19 Pandemic, Volume 1, pages 15–36.

Kuromiya, H., Majumdar, R., Miyabe, G., and Ogata,

H. (2022). E-book-based learning activity during

covid-19: engagement behaviors and perceptions of

japanese junior-high school students. Research and

Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 17(1):1–

15.

Kusano, K., Frederiksen, S., Jones, L., Kobayashi, M.,

Mukoyama, Y., Yamagishi, T., Sadaki, K., and

Ishizuka, H. (2013). The effects of ict environment on

teachers’ attitudes and technology integration in japan

and the us. Journal of Information Technology Edu-

cation: Innovations in Practice, 12(1):29–43.

Lehdonvirta, V. and R

¨

as

¨

anen, P. (2011). How do young

people identify with online and offline peer groups? a

comparison between uk, spain and japan. Journal of

Youth Studies, 14(1):91–108.

Nastasi, B. K. (2017). Cultural competence for global re-

search and development: Implications for school and

educational psychology.

OECD (2005). The role of the national qualifications sys-

tem in promoting lifelong learning: Report from the-

matic group 2—standards and quality assurance in

qualifications with special reference to the recognition

of non-formal and informal learning.

OECD (2018). PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical

Framework: Global Competence. Accessed on: Jan

18, 2023.

OECD (2020). Strengthening online learning when schools

are closed: The role of families and teachers in sup-

porting students during the COVID-19 crisis. OECD

Publishing.

Osemeke, M. and Adegboyega, S. (2017). Critical review

and comparism between maslow, herzberg and mc-

clelland’s theory of needs. Funai journal of account-

ing, business and finance, 1(1):161–173.

Parkinson, A. (2009). The rationale for developing global

competence. Online Journal for Global Engineering

Education, 4(2):2.

Parr, J. M. and Townsend, M. A. (2002). Environments,

processes, and mechanisms in peer learning. Inter-

national journal of educational research, 37(5):403–

423.

Pass, S. (2004). Parallel paths to constructivism: Jean Pi-

aget and Lev Vygotsky. IAP.

PCTL (2021). Strategies for teaching: Case-based learning.

Accessed on: Jan 18, 2023.

Pfister, D. S. (2011). Networked expertise in the era of

many-to-many communication: On wikipedia and in-

vention. Social Epistemology, 25(3):217–231.

Pinheiro, M. M. and Sim

˜

oes, D. (2012). Constructing

knowledge: An experience of active and collabora-

tive learning in ict classrooms. Procedia-Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 64:392–401.

Pinto, M. and Leite, C. (2020). Digital technologies in sup-

port of students learning in higher education: litera-

ture review. Digital Education Review, (37):343–360.

Rao, H., Puranam, P., and Singh, J. (2022). Does design

thinking training increase creativity? results from a

field experiment with middle-school students. Inno-

vation, 24(2):315–332.

Ritzer, G. and Dean, P. (2019). Globalization: the essen-

tials. John Wiley & Sons.

Saito, S. (2018). Japan at the summit: Its role in the West-

ern Alliance and in Asian Pacific co-operation. Rout-

ledge.

Saunders, L. and Wong, M. A. (2020). Instruction in li-

braries and information centers: An introduction.

Saykili, A. (2019). Higher education in the digital age: The

impact of digital connective technologies. Journal of

Educational Technology and Online Learning, 2(1):1–

15.

Tateno, M., Teo, A. R., Ukai, W., Kanazawa, J., Katsuki,

R., Kubo, H., and Kato, T. A. (2019). Internet ad-

diction, smartphone addiction, and hikikomori trait in

japanese young adult: social isolation and social net-

work. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10:455.

Tichnor-Wagner, A. and Manise, J. (2019). Globally

competent educational leadership: A framework for

leading schools in a diverse, interconnected world.

Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development and Longview Foundation.

Topping, K. J. (2005). Trends in peer learning. Educational

psychology, 25(6):631–645.

Tsang, K. K., To, H. K., and Chan, R. K. (2020). Nurtur-

ing the global competence of high school students in

shenzhen: The impact of school-based global learn-

ing education, knowledge, and family income. KEDI

Journal of Educational Policy, 17(2).

Vygotsky, L. and Cole, M. (2018). Lev vygotsky: learn-

ing and social constructivism. Learning Theories for

Early Years Practice, 58.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

534