Exploring Situational Leadership Using Critical Incident Technique

in the Times of COVID-19

Tshidi Machaba

1a

, Melani Prinsloo

1b

, Malcolm Ferguson

1c

and Pedro Ribeiro

2d

1

Henley Business School Africa, University of Reading, Cnr of Milcliff and Witkoppen Roads,

Paulshof, Sandton, 2191, South Africa

2

ALGORITMI Research Center, University of Minho, Campus de Azurem, 4800-058 Guimarães, Portugal

Keywords: Leadership, Project Management, Success, Agility, Crisis.

Abstract: The success of any project is a direct function of project leadership. Projects undertaken in a changing

environment require project managers who can adapt their leadership style on demand. This study focuses on

the impact of situational leadership in times of crisis, specifically during the period of the COVID-19

pandemic. The methodology used was the critical incident technique, carried out through interviews with

project managers and the analysis of 128 incidents described by respondents. It was found that 78% of the

project managers used more than one type of leadership and 82% used the directive type. Based on this

research, it was possible to develop a set of rules for effective leadership in troubled situations.

1 INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought different and

complex challenges for companies. The need for

rapid change, agility, and sustainability are closely

linked to projects and new ways of managing

projects. Leadership is important in the success of any

project (Lategan and Fore, 2015). A successful leader

motivates and inspires the team, manages conflicts,

and makes the right decisions to ensure the success of

projects.

Situational leadership is a leadership model that

suggests leaders should adapt their leadership style to

maximise team performance by considering the

demands of the situation. The model, initially

presented by Hersey and Blanchard (1969), suggests

four styles of situational leadership: directing,

coaching, supporting, and delegating.

This study aims to address the following research

question: what types of situational leadership helped

to manage projects successfully during the COVID-

19 pandemic? The Critical Incident Technique (CIT)

was considered the most appropriate method for this

study, as it allows details to be gathered about specific

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3973-5074

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6836-6285

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0044-3517

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3538-9282

events that occurred during a project. Eighteen

interviews were conducted with project managers in

South African companies that developed projects in

the areas of health and information technologies. In

total, 128 incidents were collected and analysed.

The next sections present the work performed and

the main results obtained. In section 2, based on a

literature review, the main concepts of CIT,

situational leadership, and project success are briefly

presented. In section 3, the research methodology is

presented, detailing the sample selection, the profile

of the respondents, and the protocol used in the

interviews. The main results are presented in section

4 describing the types of situational leadership used

by the interviewed project managers and discussing

the main findings. Finally, the last section provides an

overall analysis and summarises the main results.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

This study analyses the impact of situational

leadership on project success using CIT. This section

98

Machaba, T., Prinsloo, M., Ferguson, M. and Ribeiro, P.

Exploring Situational Leadership Using Critical Incident Technique in the Times of COVID-19.

DOI: 10.5220/0011974200003494

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2023), pages 98-106

ISBN: 978-989-758-646-0; ISSN: 2184-5891

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

describes the main concepts about CIT and situational

leadership. Moreover, a brief background on the field

of project management is presented.

2.1 Situational Leadership

The general idea of situational leadership is that there

is no single leadership style that adequately addresses

the needs of an organisation, but rather that leaders

must adapt their style to match the specific context or

situation.

The Hersey and Blanchard (1982) situational

leadership theory is based on the premise that one

must consider the characteristics of the leader and

followers as well as the situation to determine the

most appropriate form of leadership. The model

suggests that there are four primary leadership styles:

telling, selling, participating, and delegating.

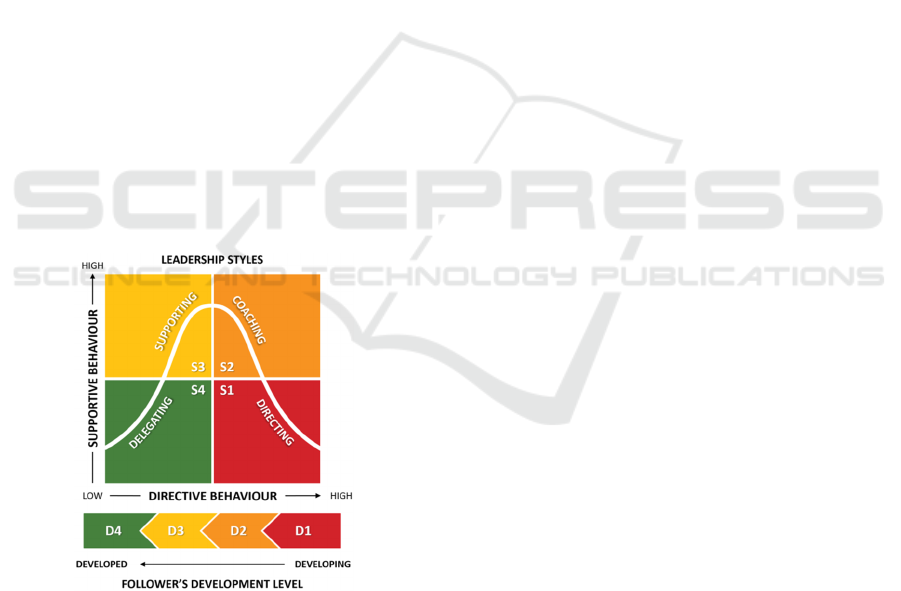

Blanchard revised the situational leadership

model and published an updated version as

Situational Leadership II (SLII) in the book,

Leadership and the one minute manager (Blanchard

et al. (1986). The model posits that, in selecting their

leadership type, team leaders will consider the degree

of direction they need to give their members versus

the level of support they should offer. Accordingly,

the SLII model has two dimensions – directive

behaviour and supportive behaviour – as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Situational Leadership II model (Blanchard et al.,

1986).

The model includes four basic types of leadership,

derived by combining the two dimensions mentioned:

1. Directing (S1): leaders provide more direction

than support to team members.

2. Coaching (S2): leaders provide high levels of

direction and support to team members.

3. Supporting (S3): leaders provide more support

than direction to team members.

4. Delegating (S4): leaders provide limited

direction and support to team members.

The model also indicates that the shift from S1

(directing) to S4 (delegating) aligns to the

development level of those being led, where D1

denotes a developing team member and D4 denotes a

developed team leader. Development level refers to

the extent to which a person has mastered the skills

necessary for the task at hand and has developed a

positive attitude towards the task. This development

level range with two dimensions of competence and

commitment replaces the performance readiness

range with dimensions of ability and willingness of

the original model. The reasoning is that competence

is perceived as something that can be developed,

whereas ability is seen as natural ability. Equally,

commitment may simply diminish over time, rather

than suggesting a lack of willingness, which is seen

as stubborn resistance in many countries (Blanchard

et al., 1993).

A more recent study tested three basic

assumptions of the SLII model, namely that the

model’s four leadership styles are both received and

required by followers; and that where followers

reported a fit between the style they needed and the

style they received, they demonstrated better

performance (Zigarmi and Roberts, 2017). Their

study highlighted the importance of both the initiating

structure and consideration dimensions of the SLII

model in various combinations. Three of the four

leadership styles of the SLII framework were reported

as frequently received, with minimal reports of high

directive-low supportive leadership. That said, all

four of the leadership styles were reported as needed.

This study also found that follower-reported fit

between one’s needed and received leadership style

at work resulted in more favourable scores on nine of

the 10 employee outcomes, compared to follower-

reported misfit. This indicates that leaders must adapt

their styles to their followers’ needs for optimal

performance.

2.2 Critical Incident Technique

Over the past decade, there has been an increasing

interest in people’s subjective impressions of life –

whether work-related, service and product

experiences or personal endeavours. The stories

people tell give researchers and practitioners insight

into how people make sense of the environment in

which they operate. This has helped researchers and

participants to learn, reflect, and improve the outcome

Exploring Situational Leadership Using Critical Incident Technique in the Times of COVID-19

99

of their efforts. Within the context of leadership

studies, specifically situational leadership, the field

benefits from research techniques that highlight the

subjectivity of experience, the layers of meaning

attached to leader and non-leader actions, and the

experiences most characteristic of general

organisational life (Bott and Tourish, 2016).

CIT has been used in a multitude of settings and

industries (Swanson et al., 2021; Ruiz et al. 2016)

doing just that – exploring subjective experiences to

help solve real problems (Davis, 2006). It is ideally

suited to uncover and unpack these experiences using

a systematic approach to obtain rich, qualitative

information about significant incidents from first-

hand experience. In this case, situational leadership in

technology and health projects was explored over the

COVID-19 pandemic timeline (January 2020 to

December 2021) by asking research participants to

describe how their behaviour, actions, or an

occurrence positively or negatively impacted a

specified project outcome.

CIT is a tool used to gather and analyse

information on behaviours that impact performance

by uncovering the skills, attitudes, knowledge, and

values at play. Flanagan (1954) listed the five CIT

steps to follow to secure these outcomes, namely to:

1. Ascertain the general aims of the activity being

studied;

2. Make plans and set specifications;

3. Collect the data;

4. Analyse the data; and

5. Interpret the data and report the results.

CIT is frequently used to collect data based on

observations reported from memory. This is usually

satisfactory when the incidents are recent and the

observers made detailed observations and evaluations

at the time of the incident.

To mitigate the risk of poor recall, which could

negatively impact the quality of the responses and the

interview time, it is suggested that researchers email

the interview guide to the participants one week in

advance (Bott and Tourish, 2016) and ask them to

think about critical incidents to discuss. Incidents can

also be restricted to those that occurred in the past

year, although this may be problematic in cases where

many incidents need to be collected.

However, in this study, the focus on the

COVID-19 time frame is sufficiently recent and, in

some ways, distinct due to the pandemic’s impact on

human lives and on the businesses they work in.

Variations in context are critical as they are likely

to lead to different results and thus implications.

Therefore, the importance of probing questions to

uncover any intricacies in the fact-finding stage of the

interview must be emphasised. Damoah (2018) and

Mol et al. (2017) contended that the dearth of studies

on Africa implies a current lack of understanding of

pertinent management issues, and have called upon

management scholars worldwide to examine the

extent to which Africa can influence existing theories.

2.3 Project Management

Projects are designed to fulfil the strategic needs of an

organisation, such as market demand, customer

requests, technological advances, legal requirements,

social needs, and crisis handling (Anantatmula,

2020). According to Gardiner (2017) a project is a

temporary effort that exists, is unique, takes shape

through progressive elaboration of processes and

standards, and is mostly defined by the complexity,

size, and scope. Minelli (2020) attested that a project

is a temporary effort to create a unique product,

service, or a result, and has a definite start and end.

The project management knowledge areas consist

of integration, scope, time cost, quality, human

resources, communication, risk, procurement, and

stakeholder management (Demirkesen and Ozorhon,

2017). Project management is the application of

processes, methods, skills, knowledge, and

experience to achieve specific project objectives

according to the project acceptance criteria within

agreed parameters (Kerzner, 2018).

Different authors attest that an event is deemed a

project if it meets the following criteria:

• Defined start and end dates;

• Defined objectives and desired results; and

• Budget and scope.

Although there might be more or fewer criteria in

a project, there is a consensus that the above are

instrumental to the definition of a project.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research aimed to explore the impact of

situational leadership in times of crisis, specifically

the COVID-19 pandemic between January 2020 and

December 2021. The focus was on critical incidents

that impacted commercial projects undertaken by

companies through medical or technological

advancements.

The interpretive and exploratory nature of this

study favoured a qualitative approach. CIT was

identified as a suitable method, as it allows for the

emergence, rather than the imposition, of a collection

of incidents based on salient and memorable

respondent experiences (Tuuli and Rowlinson, 2010).

FEMIB 2023 - 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

100

The practicality of CIT in project management

research has been demonstrated in several studies

(Haussner et al., 2016; Kaulio, 2008; Varajão et al.,

2014) and its appropriateness for this study was

further underscored by its demonstrated reliability,

validity, and practicality. Therefore, CIT was used in

this study for the following reasons (Ramseook-

Munhurrun, 2016):

• Positive and negative critical incidents could be

identified, allowing researchers to examine the

incidents most significant to the problem being

studied.

• Being inductive in nature, hypotheses were not

needed, allowing the development of concepts

and theories.

• Since the critical incidents are personal

experiences, new research evidence related to the

phenomena studied could be generated.

• Project managers could use the information

derived from the CIT for project improvements.

• The CIT research approach is important for

evaluating respondents’ attitudes from various

projects and settings.

Inductively designed critical incident interviews

were conducted to explore the behaviours and actions

of project leaders and team members to identify

alternative influences arising from other

organisational actors and contextual factors (Bott and

Tourish, 2016). Since context is crucial in research,

the choice of the empirical context was deemed

appropriate, given the scant attention being paid to

research in Africa (Damoah, 2018). Consequently,

semi-structured critical incident interviews were used

to collect behavioural data from 18 participants from

17 South African organisations working on

technology and/or health interventions during the

pandemic.

3.1 Sample Selection

Based on its success in previous CIT studies, a

convenience sampling approach was adopted to select

participants (Gremler, 2004). Participants included

project sponsors, project managers, project team

members, engineers, designers, and analysts working

on commercial technology- or health-related projects

that addressed COVID-19 challenges. This diversity

of respondents was to ensure that incidents collected

were comprehensive in their coverage of the varied

perspectives represented in project settings

(Flanagan, 1954).

Sample size in CIT studies is determined by the

number of critical incidents, rather than the number

of interviews required to achieve adequate coverage

of the subject of study, as well as the complexity of

the problem under investigation (Tuuli and

Rowlinson, 2010). Flanagan (1954) suggested that “if

the activity or job being defined is relatively simple,

it may be satisfactory to collect only 50 incidents. On

the other hand, some types of complex activities

appear to require several thousand incidents for an

adequate statement of requirements.” Flanagan added

that the investigator needs to be cognisant of

saturation, where the addition of further participants

reveals few new critical incident behaviours.

Overall, 18 interviews were conducted, each

lasting on average one hour. Interviews were

recorded and respondents’ demographic information

captured with their consent. Respondents were

requested to recall specific incidents related to the

project in their own words. Probes were used to

ensure detailed descriptions. To generate the

incidents, respondents were asked to describe the

positive or negative critical incident that contributed

significantly to the outcome of the project. In total,

128 incidents were collected. CIT allowed

respondents to “speak for themselves”, providing an

authentic understanding of critical incidents and

insights related to the success of the project under

COVID-19 conditions.

Analysis was done by examining the text for

narrative structures to identify insights that emerged

from the data. Working in teams, the analysts

categorised the critical incidents related to situational

leadership impacting project success, in the process

also validating the categories (Butterfield et al. 2005).

3.2 Profile of Respondents

Eighteen project managers and project sponsors from

the technology and health sectors were interviewed

via online platforms (i.e., Zoom and Microsoft

Teams). The interviews were recorded digitally and

transcribed. Majority of respondents were from the

technology sector (82%), only three worked in health

(18%).

During the interviews, respondents shared a

project they completed between January 2020 and

December 2021 and recalled the critical incidents in

the project’s life cycle. The projects were diverse in

nature and included establishing a command centre,

helping private hospitals navigate the challenges and

opportunities posed by COVID-19, delivering

733 000 laptops to learners registered at technical and

vocational colleges, offering innovative technology

solutions to large manufacturing and retail banking

companies, and shifting a call centre to agents’

homes. Two of the projects were in companies that

Exploring Situational Leadership Using Critical Incident Technique in the Times of COVID-19

101

were on the brink of closure at the onset of COVID-

19 and managed to become sustainable businesses

during the pandemic. The diversity of projects

together with the precarious financial positions of

some of the companies strengthened the data set and

contributed to its reliability.

3.3 Interview Protocol Development

As emphasised in section 2, a clear definition of a

critical incident, within the context of the study, is

important to ensure that participants do not

necessarily see it as a crisis and/or a negative event.

For the purpose of this study, a critical incident is a

decision and/or action undertaken by a project team

member (or a person not directly involved in the

project) that contributed significantly to the project

outcome in terms of:

• Efficiency measured as duration, cost, or

resources required;

• Contribution to business sustainability; and/or

• Impact on participants, beneficiaries, or other

stakeholders.

The research team carefully considered whether

the interview guide should specify the identification

of both positive and negative incidents. If not, it was

more likely that respondents would recall negative

incidents (Davis, 2006), which have longer-lasting

and more intense consequences. After a thorough

review of literature, it was decided to request both

positive and negative incidents for this study to reveal

a commonly experienced range of challenges and

situations, as well as diverse themes that may vary

across different contexts. The question that was posed

– describe the positive/negative critical incident

(decision/action that contributed significantly to the

outcome of the project) – does not presume that all

(or any) leadership behaviours will be relevant, as the

research design does not deductively consider

behaviours prescribed by a particular leadership

theory at its onset.

To find a balance between clarity and dialogue,

without invoking unnecessary response bias, the

probes listed below were used in the study. They were

designed to minimise structure in the interview

process and ensure that the discussion was driven by

what the respondents felt was important.

• What could have made the action more effective?

• Which aspect of the project outcome was most

affected? Please explain why you think so.

• What was the project role of the person who took

the unplanned action you described?

• In what way do you believe the critical incident

contributed to the project outcome?

• What were the negative/positive effects of the

critical incident on the project outcome?

• What could the person have done differently to

have a more positive effect on the project

outcome?

• What do you believe equipped the person to

make this contribution (rank in order of

importance)?

4 ANALYSIS AND REPORTING

This section presents the critical incidents identified

from 18 transcripts of interviews conducted with

project sponsors and project managers of 17 different

companies. A total of 128 incidents were reported.

This analysis is presented in two sections: 1) types of

situational leadership employed by project managers

and 2) discussion of findings.

4.1 Types of Situational Leadership

Used by Project Managers

For the purpose of this study, each critical incident

was categorised according to the four basic types of

situational leadership (i.e., directing, coaching,

supporting, and delegating). In most of the projects

considered (82%), more than one type of situational

leadership was used to achieve success (Table 1).

Two of the three projects in the health sector used a

combination of three types of situational leadership to

deliver on their goals, while a third (33%) of

technology projects used three types of situational

leadership.

Table 1: Number of situational leadership (SL) types used

to deliver projects.

Sector

One

type of

SL

Two

types of

SL

Three

types of

SL

Four

types of

SL

Health 0 1 2 0

Technology 3 5 5 1

Total 3 6 7 1

% 18% 35% 41% 6%

The technology company that blended all four

types of situational leadership delivered a unique

project to clients. Historically, the company provided

only electronic components to its clients. During the

pandemic, for the first time, the company offered its

clients a full technology solution, both hardware and

software, to vertically integrate its parts into a

complete solution for clients. To accomplish this, the

company rolled out a multidisciplinary team. Prior to

FEMIB 2023 - 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

102

COVID-19, the company was put up for sale because

it was seen as a commodities business and, at the

onset of the pandemic, it had to retrench staff to

remain competitive. The remaining employees were

given ongoing training to ensure a full understanding

of all aspects of the business to enable growth. The

team was supported to keep employees engaged

throughout the project by implementing various

virtual social activities, such as “virtual cook-offs”.

The outcome of the situational leadership was that

clients now saw the company as a partner in the

growth and development of their businesses.

Importantly for the company, it has not only remained

in business, but is now also able to offer a unique

service to its clients, with multiple growth

opportunities.

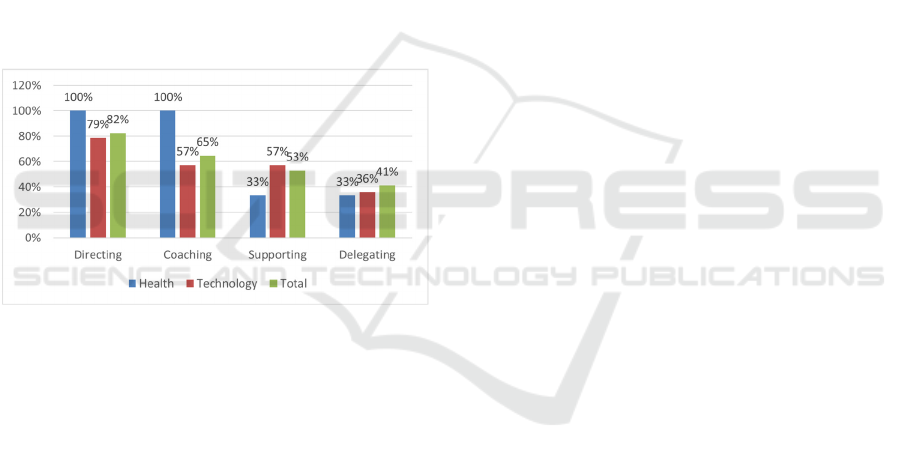

Four in five (82%) project managers used the

directing type of situational leadership to deliver their

respective projects. This was followed by coaching

(65%), supporting (53%), and delegating (41%), as

illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Types of situational leadership by sector.

The critical incidents related to directing (S1)

comprised decisions to continue to offer services

during the various iterations of COVID-19

lockdowns. This was accomplished by a multitude of

decisions and activities, namely:

• Going online and allowing and enabling their

employees to work remotely;

• Offering new services and products relevant to

the pandemic conditions;

• Creating new structures to mitigate the impact of

COVID-19;

• Adapting traditional project management

methodology by reducing the planning phase;

• Increasing the frequency of risk assessment

meetings; and

• Extending the duration of status meetings to

allow for learning and bonding, and breaking

down tasks into smaller outputs to demonstrate

delivery and keep team members connected.

Coaching (S2), as another situational leadership

style, was used by two-thirds of project managers to

provide their employees with emotional support and

help them remain connected during COVID-19. The

critical incidences included:

• Providing training;

• Conducting regular online risk assessment

meetings complemented by longer routine

project status meetings;

• Sharing information continuously; and

• Providing frameworks for operations in the time

of COVID-19.

Other areas of coaching allowed branches to

formulate standard operating procedures related to

their unique contexts. These comprised:

• Transferring skills to partner organisations;

• Helping clients consider organisational cultures

in how they deliver products and services;

• Assisting employees to be heard during online

meetings; and

• Trusting employees to work remotely.

Half the projects used the supporting (S3)

capability of situational leadership. The critical

incidences in this category included:

• Drawing on the company’s physical and

intellectual resources;

• Increasing the frequency of reporting back to

project team members;

• Helping team members remain connected while

working remotely, creating virtual social events;

• Employing counsellors to help employees cope

with COVID-19 and working remotely;

• Building trust amongst team members; and

• Understanding the cultural diversity of

employees, and ensuring that meetings were

“intentional and impactful”.

The delegating (S4) situational leadership

capability was used mainly by project managers who

had to deliver on large and complex tasks through

multidisciplinary teams. While many of these projects

used traditional project management methodology,

during COVID-19, they adapted these to meeting

more often for short risk assessment updates,

reducing the size and time of incremental outcomes,

and using more time for progress meetings to share

learnings and facilitating connectedness. As such, the

critical incidences were:

• Meeting daily to assess risk;

• Providing clear instructions or standard

operating procedures;

• Authorising team leaders to take final decisions;

and

• Trusting team members.

Exploring Situational Leadership Using Critical Incident Technique in the Times of COVID-19

103

Of the three companies that did not use the

directing situational leadership capability, one

applied only the delegating capability, one employed

only coaching, and one practised both coaching and

supporting. The project that used the delegating

situational leadership was steeped in this practice. It

was a project of a company with offices across the

globe and offered services in diverse country

jurisdictions through multidisciplinary teams

resourced with members from the different offices.

Consequently, the COVID-19 lockdown reduced the

company’s face-to-face interactions with its clients,

but had limited impact on the teams. Nonetheless,

they did make changes, which included meeting more

frequently online. The company delivered its projects

earlier than planned.

4.2 Discussion of Findings

At the onset of COVID-19 lockdowns, project

managers had to make decisions quickly to ensure all

their business functions continued to operate, offered

new services and products in response to the

exigencies of the pandemic, protected their revenue

streams, prevented closure of their businesses, and

safeguarded their employees’ well-being.

Consequently, the directing situational leadership

capability was used by majority of project managers.

Those who did not use the directing capability were

technology companies that had historically worked

with teams dispersed across offices and countries.

These companies had experience working remotely

and focused on improving their coaching and

delegation situational leadership capabilities.

Nonetheless, working remotely brought to the

fore the importance of enabling and supporting

employees during the pandemic and helping their

respective clients to enhance their business

performance. As such, project managers combined

directing with coaching, supporting, and delegating

capabilities. The coaching capability was frequently

utilised because it allowed project managers to build

trust by increasing their employees’ technical and

emotional capabilities. Furthermore, supporting

situational leadership capabilities were used to help

employees remain connected during a pandemic

when everyone was feeling isolated and dealing with

illness, loss of family members, and the fear of job

loss.

The COVID-19 pandemic appeared to have

served as a catalyst to not only consider remote

working as an option, but it underscored the

companies’ soft skills, especially their culture and

their employees’ emotional well-being. A notable

finding was the adaptation of traditional project

management methodologies to respond to the

COVID-19 pandemic. Project managers recognised

that to successfully deliver on projects with their team

members working remotely and limited face-to-face

interaction with their clients, they had to frequently

provide evidence of progress. Additionally, they

recognised that there were too many variables at play,

which increased risk and uncertainty daily.

Consequently, they made five changes to the

traditional project management methodology,

namely:

• Reducing the planning time so that clients would

feel the “heightened” sense of urgency towards

the critical delivery;

• Emphasising “incremental delivery” where they

further broke down outputs into smaller pieces of

work that could be used to frequently report on

progress;

• Conducting frequent risk assessment meetings

where many of the projects met daily for a few

minutes to “clock in” and get a quick assessment

of team members’ progress and emotional well-

being, and to identify and mitigate any new risks.

• Running longer project status meetings to

include learning and feedback opportunities,

which helped keep their team members

connected; and

• Offering many virtual social opportunities for

team members and clients to remain connected

and ensure their emotional well-being.

While COVID-19 amplified time and resources,

project managers took this as a given and believed

that the criteria of success on their projects were user

satisfaction, business and commercial performance,

and quality performance. These latter criteria were

considered critical in ensuring that their businesses

were sustainable. Analogously, project success

factors were expanded to include building trust,

collaborating, and ongoing communication with

internal and external stakeholders.

The study confirmed that situational leadership

offers a useful model for understanding leadership in

project management due to its contingency-based

assumption. COVID-19 offered not only a means to

test this assumption, but to also examine the model’s

veracity. In this study, project managers’ decisions

were not only shaped by the exigencies of the

pandemic, but also by the level of development or

maturity of their teams and clients and the complexity

of the projects as described above. COVID-19

underscored the significance of trust and

connectedness amongst team members and between

the project team and the client as project success

FEMIB 2023 - 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

104

factors. Project managers, who recognised these

enabling factors, combined directing with coaching

under the situational leadership types. The coaching

situational leadership type allowed project managers

to build trust and keep both internal and external

stakeholders connected.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Project managers used a combination of situational

leadership types during COVID-19 to accommodate

the many unknown variables affecting their projects

and the related uncertainties in a changing

environment. They made directive decisions at

executive level, including working remotely to ensure

that business functions continued. Concomitantly, to

ensure success, project managers applied the

coaching situational leadership capability to ensure

their employees were empowered and remained

connected.

Ultimately, company leaders trusted employees to

work remotely because they had no alternative under

the strict national lockdown. This led to a distributed

working model applied at an unprecedented scale

worldwide and with great success. This distributed

workforce would have been impossible without

technologies and many technologies were developed

or refined to facilitate the shift. Equally, the increased

reliance on technology required an intentional

emphasis on human connection and the success

stories point to leadership that was able to harness and

weather the COVID-19 pandemic.

While it is tempting to conclude that remote

working should become the new norm beyond the

lifting of COVID-19 restrictions, it is important to

bear in mind the unique context in which the remote

working model succeeded. Perhaps the most

significant aspect of the COVID-19 context was the

fact that, just as managers were sceptical of trusting

their teams to take accountability without

supervision, employees were understandably anxious

about being retrenched and eager to demonstrate their

value to their organisations.

The situational leadership model points to a need

for agility and responsiveness on the part of leaders,

so there is a need to adopt a situational work model

that accommodates varying combinations of office-

based and remote working. Perhaps the most valuable

lesson from our collective COVID-19 experience is

that human beings are, at our best, agile, resilient, and

inclusive, and, at our worst, stubborn, fickle, and

dictatorial.

The results obtained suffer from some limitations

resulting mainly from the difficulties in collecting

more detailed data from the projects. It should also be

noted that it would be important to interview

participants other than project managers. The lack of

information about leadership styles before COVID is

also a limitation of the study. As future work it is

intended to continue the investigation in order to:

obtain in a reliable way the relationship between the

leadership styles and the results (positive or

negative); study how the leadership styles coexist /

evolve during a project; understand in a quantitative

way which are the impacts of the leadership styles on

the success criteria.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Participants in the Latin American Council of

Management Schools (CLADEA) Project

Management Research Group focusing on the

‘impact of situational leadership in times of crisis on

project outcome’.

- This work has been supported by FCT – Fundação

para a Ciência e Tecnologia within the R&D units

Project Scope: UIDB/00319/2020.

REFERENCES

Anantatmula, V.S., 2020. Project Management Concepts.

In Operations Management-Emerging Trend in the

Digital Era. IntechOpen.

Blanchard, K. H. (n.d.). Situational Leadership II: A

dynamic model for managers and subordinates.

Executive Excellence [Preprint].

Blanchard, K. H., Zigarmi, P., & Zigarmi, D. (1986).

Leadership and the one minute manager. Collins.

Blanchard, K. H., Zigarmi, D., & Nelson, R. B. (1993).

Situational Leadership

®

after 25 years: A retrospective.

Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 1(1),

21–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179199300100104.

Bott, G., & Tourish, D. (2016). The critical incident

technique reappraised: Using critical incidents to

illuminate organizational practices and build theory.

Qualitative Research in Organizations and

Management, 11(4), 276–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/

QROM-01-2016-1351.

Butterfield, L. D., Borgen, W. A., Amundson, N. E., &

Maglio, A.-S. T. (2005). Fifty years of the critical

incident technique: 1954-2004 and beyond. Qualitative

Research, 5(4), 475-497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468

794105056924.

Damoah, O. B. O. (2018). A critical incident analysis of the

export behaviour of SMEs: Evidence from an emerging

market. Critical Perspectives on International

Exploring Situational Leadership Using Critical Incident Technique in the Times of COVID-19

105

Business, 14(2/3), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1108/

cpoib-11-2016-0061.

Davis, P. J. (2006). Critical incident technique: A learning

intervention for organizational problem solving.

Development and Learning in Organizations, 20(2),

13–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777280610645877.

Demirkesen, Sevilay, and Beliz Ozorhon. (2017). "Impact

of integration management on construction project

management performance." International Journal of

Project Management 35, no. 8 (2017): 1639-1654.

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique.

Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327–357. https://doi.org/

10.1037/h0061470.

Gardiner, P., 2017. Project management: A strategic

planning approach. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Gremler, D.,D. (2004) The Critical Incident Technique in

Service Research. Journal of Service Research, Vol 7,

No. 1, Aug (65-89).

Haussner, D., Maemura, Y., & Matous, P. (2016).

Exploring critical incidents in international

construction projects [Conference presentation]. 7th

Civil Engineering Conference in the Asian Region

(CECAR), Waikiki, Oahu, Hawaii.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Life cycle theory of

leadership. Training & Development Journal, 23(5),

26–34.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1982). Management of

organizational behavior: Utilizing human resources

(4th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Lategan, T., & Fore, S. (2015). The impact of leadership

styles on project success: Case of a telecommunications

company. Journal of Governance & Regulation, 4(3),

48–56. https://doi.org/10.22495/jgr_v4_i3_p4.

Kaulio, M. A. (2008). Project leadership in multi-project

settings: Findings from a critical incident study,

International Journal of Project Management, 26(4),

338–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.06.0

05.

Kerzner, H. (2018). Project management best practices:

Achieving global excellence. John Wiley & Sons.

Minelli, P. (2020). Improved methods for managing

megaprojects (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts

Institute of Technology).

Mol, M. J., Stadler, C., & Ariño, A. (2017). Africa: The new

frontier for global strategy scholars. Global Strategy

Journal, 7(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1146.

Ramseook-Munhurrun, P. (2016). A critical incident

technique investigation of customers’ waiting

experiences in service encounters. Journal of Service

Theory and Practice, 26(3). https://doi.org/10.1108/

JSTP-12-2014-0284.

Ruiz, C. E., Hamlin, R. G., & Carioni, A. (2016).

Behavioural determinants of perceived managerial and

leadership effectiveness in Argentina. Human Resource

Development International

, 19(4), 267–288.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2016.1147778.

Swanson, S. R., Davis, J. C., Gonzalez-Fuentes, M., &

Robertson, K. R. (2021). In these unprecedented times:

A critical incidents technique examination of student

perceptions of satisfying and dissatisfying learning

experiences. Marketing Education Review, 31(3), 209–

225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2021.1952082.

Tuuli, M. M., & Rowlinson, S. (2010). What empowers

individual and teams in project settings? A critical

incident analysis. Engineering Construction and

Architectural Management, 17(1), 9–20.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09699981011011285.

Varajão, J., Dominguez, C., Ribeiro, P., & Paiva, A. (2014).

Critical success aspects in project management:

similarities and differences between the construction

and the software industry. Tehnički Vjesnik – Technical

Gazette, 21(3), 583–589.

Zigarmi, D., & Roberts, T. P. (2017). A test of three basic

assumptions of Situational Leadership

®

II Model and

their implications for HRD practitioners. European

Journal of Training and Development, 41(3), 241–260.

https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-05-2016-0035.

FEMIB 2023 - 5th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

106