Easierphone: Participative Development of a Senior-Friendly

Smartphone Application

Sarah Speck

1a

, Cora Pauli

1b

, Cornelia Ursprung

1c

, Robert Huber

2

,

Katja Antonia Rießenberger

3d

and Sabina Misoch

1e

1

Institute for Ageing Research, University of Applied Sciences of Eastern Switzerland, Rosenbergstrasse 59,

9001 St.Gallen, Switzerland

2

Pappy GmbH, Flüelastrasse 6, 8048 Zurich, Switzerland

3

Bavarian Research Center for Digital Health and Social Care, Kempten University of Applied Sciences,

Albert-Einstein-Straße 6, 87437 Kempten, Germany

sabina.misoch@ost.ch

Keywords: Ageing, AI, Digital Divide, Digitalization, Older Adults, Smartphone Use, Smartphone Application.

Abstract: Ageing and digitalization are two major developments of the 21st century. Particularly, smartphone ownership

increased to about over 80 % globally. Meanwhile, smartphones also gained great popularity among older

adults, nonetheless, many still show fear of contact. The multi-national project Easierphone aims at

empowering older adults and other vulnerable persons to effectively use smartphones. A senior-friendly app,

Easierphone, simplifies smartphones while replacing the common android interface with an easier-to-use one.

In addition, the Easierphone app enables two smartphones to be connected remotely to facilitate virtual

assistance. A participative design is applied to conduct tests with older adults in three different pilots, in three

different countries. Semi-structured interviews, try-out of the app, individual follow-up discussions and co-

creation workshops are conducted to collect data. The Easierphone app to date is received positively by

potential end-users. Many of the diverse functionalities of the app could be improved with feedback from test

participants. The development process is an iterative one, in between each pilot, to achieve best possible

adjustments to the app. The preliminary results indicate that fear of contact still prevails, nonetheless. The

simplified interface seems to provide a basis for older adults to use their smartphones with more confidence.

1 INTRODUCTION

Growing numbers of older adults in society and the

parallel progress of digitalization represent two major

global developments of the 21st century. Today, the

proportion of older people is increasing fast and there

are already more people aged 60 years and older than

children younger than five (UNDESA, 2022). At the

same time, the smartphone ownership per person

increased globally to more than 83% in emerging

economies, and over 94% in advanced economies

(Pew Research Center, 2019). These two

developments are the frontrunners in Western

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9076-4121

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7925-6073

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7796-2759

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7960-9625

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0791-4991

European countries. In the age group of 55-64 years,

an average of 60% of European Union citizens used

smartphones for private purposes. Among older

adults aged 65-74 years, usage was found to account

for about 40% (Eurostat, 2018).

In Switzerland, high use of information

communication technology (ICT) was found among

older adults (Seifert et al., 2021). A total of 69% of

older adults above 65 years are using smartphones,

and the majority of them regularly (Seifert et al.,

2020). However, far less older adults over 85 years

use smartphones regularly (25%). These numbers

highlight a so-called digital divide. It is a difference

Speck, S., Pauli, C., Ursprung, C., Huber, R., Rießenberger, K. and Misoch, S.

Easierphone: Participative Development of a Senior-Friendly Smartphone Application.

DOI: 10.5220/0011974400003476

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2023), pages 199-207

ISBN: 978-989-758-645-3; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

199

in access and use of ICT among different age groups

(Francis et al., 2019). The gap exists even within the

different age groups of older adults, which once more

underlines how heterogenous this population group of

older adults is. The “grey digital divide” describes the

fact that older-old adults use ICT far less compared to

younger-old adults (Friemel, 2016; Neves & Vetere,

2019; Seifert et al., 2020).

The Covid-19 pandemic played an important role

in use of digital devices and acceleration of their

development, while at the same time showing the

importance of not leaving anyone behind. During this

time many groups were marginalized due to, e.g.,

isolation, lack of mobility, and limited social

network. Especially older adults were affected,

making them more vulnerable in our society (Seifert

& Charness, 2022). To approach this societal

challenge, older adults are being moved more into the

focus of digitalization. Additionally, the discourse

has shifted towards “what is possible” and is looking

at older adults’ digital competences rather than their

deficits. Reisdorf and Rhinesmith (2020) encourage

finding ways to alleviate the so-called digital divide

and the accompanying age-related inequalities. It

must be ensured that all citizens are included in this

progress of digitalization, particularly older adults.

Our EU research project titled Easierphone starts

precisely at this point and aims to facilitate access to

digital opportunities and the possibilities offered by

smartphones for older adults. The Easierphone app is

especially developed for a less tech-savvy target

group. The project aims to simplify smartphone usage

for mainly older adults but as well for other

vulnerable people. In doing so, the app intends to

replace the common android interface with an easier-

to-use one (e.g., bigger font, better overview,

contrast), that is uniquely adaptable to the end-user’s

respective abilities. In addition, the Easierphone app

enables two smartphones to be connected remotely to

facilitate virtual assistance in the use of smartphones

(tandem). Here, the older adult’s smartphone screen

gets mirrored on the assistant´s device screen. This

assistance can be provided by close family members,

trusted neighbours, or (in)formal caregivers. A

machine learning algorithm is currently under

development, aimed to detect changes in the older

adult´s smartphone usage to determine the well-being

of the older person by analysing smartphone usage

patterns and geolocation data.

2 FOSTERING DIGITAL

INCLUSION THROUGH A

SENIOR-FRIENDLY DESIGN

ICTs such as smartphones play an important role as

older adults strive for an independent and self-

determined life in their own homes, while still

wanting to feel safe and socially connected (Hedtke-

Becker et al., 2012; Marek & Rantz, 2000; Pani-

Harreman et al., 2021). These ICTs were proven to

provide access to social resources and to enhance

seniors’ quality of life (Francis et al., 2019).

Generally, smartphones are becoming the primary

access point for social interactions, information, and

services in our society (Castells, 2011; Seifert &

Rössel, 2019). Hence, to sustain a self-determined life

nowadays, older adults are increasingly confronted

with the demands of digitalization (Seifert et al.,

2021), particularly smartphones. Being able to use

smartphone functionalities has the potential to

considerably lower older adults' vulnerability and

increase their social connectedness to family, peers,

and formal support networks (Fernández-Ardèvol et

al., 2019). However, many senior users are unable to

fully utilize modern smartphones due to their

complexity (Awan et al., 2021).

Possessing a smartphone does not necessarily

equate to actually using the device. Older adults may

find it difficult to use modern smartphones. For the

heterogeneous group of older adults, however, classic

"senior phones" are not a satisfactory alternative. The

distinctive design, which greatly differs from a

conventional smartphone, as well as the reduction of

functionalities to mainly provide assistance

functionalities (e.g., emergency calls, localization)

can have a patronizing, stigmatizing, and

discriminating effect (Unterstell, 2007). At the same

time, the label "senior phone" evokes resistance from

an older user group as they do not perceive

themselves as a homogeneous group and do not want

to be addressed as “old” or “seniors” (Rößing, 2007).

The attitude of older adults towards digital

services is mainly predicted by their interest in

technology, as well as knowledge, and willingness to

use it (Seifert & Charness, 2022; Siren & Knudsen,

2017). Some older adults are limited in their use due

to health issues and face barriers (e.g., complexity,

accessibility, security concerns, high effort to learn

new technology, or cognitive decline) which can

further limit their access (Darvishy et al., 2021;

Seifert et al., 2020; Seifert et al., 2021). A digital

divide between the young and old generation does not

only exist for the use of smartphones, but as well

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

200

regarding digital literacy in general (i.e., access to,

and understanding of information from smartphones;

Wang et al., 2011). Digital literacy is especially

relevant for the use of services enabling a self-

determined life, such as e-health services, e-

government, or gathering of information (Tsai et al.,

2017). The lower digital literacy among older adults

can be a problem, as smartphones have evolved to

becoming the main enabler of social communication,

and other instrumental tasks required to fully

participate and function in modern society (Blažič &

Blažič, 2020). Various factors such as personal

characteristics (e.g., age, health, gender), socio-

economic and facilitating conditions (e.g., education,

expectations of social network), engagement with

ICT and digital literacy, as well as smartphone-

related beliefs and attitudes have been found to

predict older adults’ smartphone acceptance (Chen,

K. & Chan, A. H., 2014; Guo et al., 2013; Ma et al.,

2016; Petrovčič et al., 2018; Piper et al., 2016; Xue et

al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2013).

With these challenges in mind, the Easierphone

app is not only trying to simplify a smartphone’s

surface for easier handling, but to find and provide a

way for older adults to keep up with the times, for

example, by having a fashionable smartphone without

being stigmatized for using a clumsy “senior phone”.

Further, older adults should also benefit from the

various apps and functionalities that modern

smartphones entail. The Easierphone app aims to

address the challenges older adults face when using

their smartphones in daily life, to facilitate the usage

of fashionable devices and dispel some older adults'

fears in using modern digital devices. Further, the

project intends to provide an opportunity for older

adults to keep in touch with their friends and family

more easily, and simultaneously to get support for

their smartphone usage most easy.

1

Pappy GmbH (project initiator), University of Geneva,

and University of Applied Sciences of Eastern

Switzerland (IAF)

2

Almende, MOB Drechtsteden B.V. Internos

3

ASM - Market Research and Analysis Center

4

The development of the Easierphone app is based on the

ethical guidelines of the European Assisted Active Living

3 RESEARCH DESIGN AND

APPLIED METHODS

3.1 Easierphone: A Multi-National

Project

Easierphone is a research project embedded within

the European Assisted Active Living (AAL) funding

programme which aims to create better quality of life

for older adults, fostering cooperation between

research and industry. The duration of the entire

project spans 30 months, starting in April 2021 and is

expected to finish September 2023. The project

consists of six project partners from Switzerland

1

, the

Netherlands

2

, and Poland

3

. Easierphone is not only

designed for older adults, but also with older adults

by using participatory design methods.

To ensure good progress in developing the app, it

is tested continuously during three sequential project

phases (pilot 1, 2 and 3) in usability tests with

potential end-users (seniors, relatives). In pilot 1, the

assistance functionality for tandem use was neither

developed nor used. Pilot 1 aimed to get familiar with

the app and to collect general information about

smartphone use and challenges in daily life of older

adults. Pilot 2 mainly tests the assistance functionality

of Easierphone, a tandem functionality which is used

together with an assisting person. In addition, an

artificial intelligence module (AI module, which

consists of activity tracking, i.e., pedometer and daily

routes taken) is planned to be integrated. Here,

questions regarding privacy, data protection and

ethics (as seen from the perspective of the

participants) are of central interest

4

, as transparency

is of utmost relevance for end-users of Easierphone.

During the testing, we meticulously explain to

participants what the app tracks, how the tracking can

be turned off, and how the participants themselves

have control over various functionalities.

For this position paper, we focus on the cases of

pilot 1 and 2 in Switzerland. Each team involved in

end-user testing is responsible for their own data

collection in its respective country. So far, the team

of the Institute for Ageing Research (IAF) has

completed pilot 1 and is currently in the process of

pilot 2. In each pilot, the IAF team execute interviews

(AAL) funding programme. From an ethical point of

view, the use of new technologies is acceptable if they do

not conflict with the integrity interests of the users, e.g.,

do not restrict self-determination and safety, and the

dignity of the users is preserved (Remmers (2019)).

Easierphone: Participative Development of a Senior-Friendly Smartphone Application

201

with three individual participants and seven tandems

5

,

resulting in a total of 30 tests in Switzerland. The

individual participant, as well as the main participant

of the tandem must be at least 65 years old. The age

of the tandem assistantsis less relevant. Most

participants who were selected for testing are people

who do not feel confident using their smartphones.

The end-user tests include a try-out of the already

implemented and developed functionalities of the

current version of Easierphone.

3.2 Applied Methods

Data collection is based on semi-structured guideline

interviews, testing the app in real life conditions with

the support of the researchers, follow-up discussions

in between the different sessions, and consecutive co-

creation workshops. Each pilot includes interviews

along with a try-out of the app. A full pilot’s

procedure follows this process: Each field test is

based on three dates with face-to-face interviews

(Misoch, 2019). In the case of Easierphone, the first

meeting with the participant(s) intends to install the

app together with the researchers on the participants’

private smartphones. A first impression of the app is

surveyed and additional information about the

participants’ general smartphone use is collected.

During the tests, participants are asked what

additional functionalities could be useful for them to

implement. The project’s approach is based on a user-

centred design (Tullis & Albert, 2013), where the app

is being tested in a real-life setting over several weeks

to allow the participants the opportunity to get to

know the app and to assess it comprehensively in an

everyday setting. This enables a deeper insight into

their actual user needs. In addition to assessing user

needs (e.g., which functionalities of the application

were used, and which ones were missing), the focus

lies on questions of usability (e.g., what problems

arise during use), as well as acceptance (e.g., which

framework conditions are central to acceptance).

The second meeting focuses on the challenges that

came up in between the first and second testing

regarding usability and further needs from the user

concerning the app. In the third meeting, testing

focuses again on questions regarding usability,

pending needs, as well as opinions on the AI modules.

As the study aims to gain a broader understanding

of older adults’ smartphone use, the researchers were

taking side notes on specific observations of

smartphone usage or challenges that came up during

5

A tandem composes an older adult and her/his adult child,

grandchild, other relatives or trustworthy friends and

neighbours.

testing (e.g., language and font size settings).

Alongside the interviews, paper and pen journaling

(done by participants) to write down challenges or

questions while using the app in absence of the

researchers was applied. The diary entries or

questions of the participants were then discussed in

the following meetings. Drawing on the experience

already gained, the feedbacks from participants, and

lessons learned from previous pilots, the app can be

further developed by programmers according to

specific needs and suggestions for improvement.

All interviews are audio recorded. For pilot 1, the

interviews conducted were protocolized and

anonymized by IAF staff. For the ongoing pilot 2, the

interviews are fully transcribed and anonymized with

the support of student assistants at IAF. Afterwards,

all text data are translated to English by IAF staff and

shared with the entire Easierphone project team to

ensure transparency of information. The coding,

categorization and prioritization are done in an

iterative technology development process where the

IAF and Pappy GmbH are working together.

To enrich the collected data from the interviews,

co-creation workshops are held following each pilot

with volunteer participants. In the co-creation

sessions selected issues from the tests are discussed

in more detail to improve future developments of the

Easierphone app. The inclusion of potential end-users

in a participative manner along the process, creates a

more tangible project for all sides, participants,

caretakers, as well as researchers, and developers

(Greenhalgh et al., 2016).

4 PRELIMINARY FINDINGS

This section first describes the results from pilot 1,

starting with end-users’ fears and concerns, followed

by the main findings of pilot 1. Next, preliminary

findings from pilot 2 are outlined. In preparation for

improvement of the app, the interview protocols

(containing the most relevant issues to discuss) of

each pilot are transferred to a table. Potential

solutions for the problems that came up during the

tests are then suggested by programmers and Pappy

GmbH. These issues are divided into the following

main categories: i) General Issues, ii) On-boarding,

iii) Phone & Contacts, iv) Messages, v) Camera &

Images, vi) Web & Alarm Clock & Magnifier, vii)

Emergency, viii) Settings, ix) 3

rd

party apps, and x)

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

202

Purchase. A few examples of these categories and

issues are shown under 4.2.

4.1 End-Users’ Fears and Concerns

The great heterogeneity among the participants

mirrors their habits and skills in handling their

smartphones. This also applies to other apps they use:

While some use their smartphone only for calls, one

person of the sample even uses it for e-banking. In

general, smartphones are mainly used for

communication and information search, in some

cases for purchasing tickets for public transport.

Among the participants, communication is an

important driver for buying and using a smartphone.

Further, security concerns appeared to be an

important topic for the participants. Most participants

say that they always carry their smartphone with them

when they are outdoors, so they can notify someone

in case of an emergency.

The following list summarizes the most common

fears and concerns that crystallized from the

interviews:

Multitude of preinstalled apps are confusing

users, or make it difficult to orientate and find

relevant apps;

Issues with or lack of knowledge on how to

personalize the home screen, or arranging apps

as needed (sometimes due to fear of accidentally

deleting relevant apps);

Difficulty downloading and installing apps;

Difficulty sending pictures from the gallery;

Issues with differing logic of various apps (e.g.,

sending a message via e-mail app, compared to

WhatsApp, or SMS app);

Lack of practice with functionalities or rarely

used apps;

Fear of deleting important content or impairing

the functioning of the device (e.g., due to

clicking the wrong button), hindering trial and

error use of the smartphone or apps;

Inexperienced and insecure users are

overwhelmed by constant changes in digital

products;

Feeling like a burden and therefore holding back

on asking social contacts for help.

4.2 Main Findings and Suggested

Adjustments from Pilot 1

Most of our participants liked the fact that the

Easierphone home screen is much clearer and easier

to read compared to the standard home screen of their

Android smartphone. They particularly favoured the

appearance of the icons arranged one below the other.

The size of the icons and the larger font in general

were also found to be positive. After the installation

of the Easierphone app, "Contacts", "Phone" and

"SMS" functionalities were automatically

synchronized, i.e., all corresponding content was

imported into Easierphone. This was rated very

positively by our participants. The opportunity to

have an emergency functionality was considered very

important.

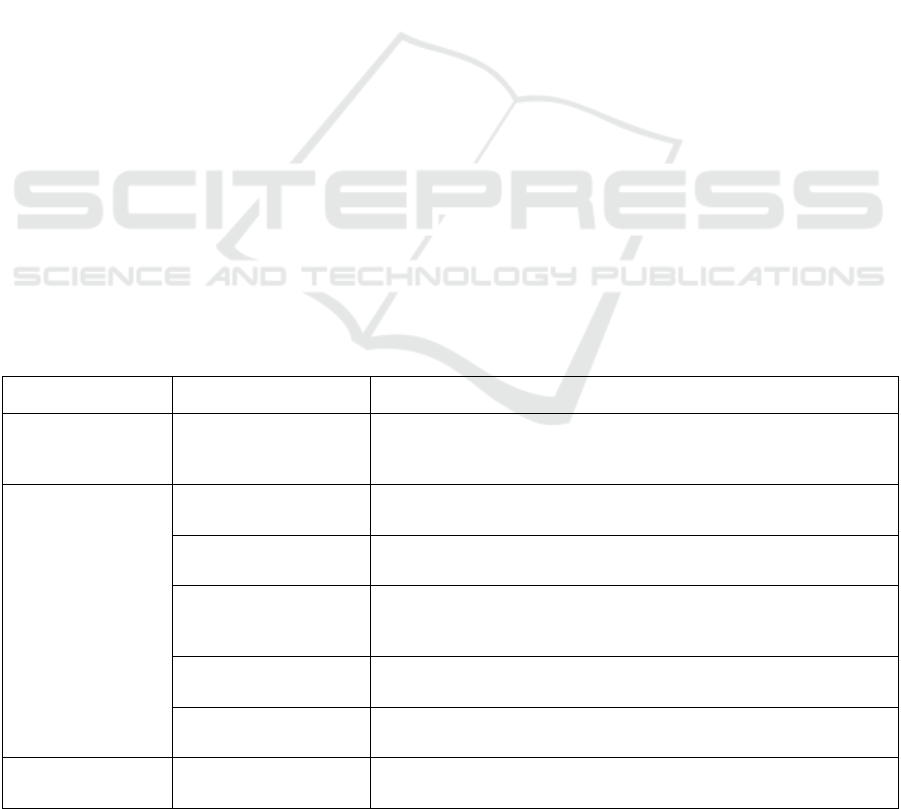

Table 1: Extract of the Table of Categories and Related Issues from Pilot 1.

Category Issue Issue description

General issues

Contact app icon

In the case of the “Contacts” tile, one participant would rather have a

symbol that looks like the usual contact apps (e.g., icon with a head

instead of icon with an address book)

Phone & contacts

Difficult to delete

contact

It is unclear how to delete a contact due to the scrolling.

Accept phone call

Participants are used to tap the button instead of “swipe” motion to

accept a call

Accept phone call

Participants prefer a bigger icon size for the phone call receiver.

Participants are used to the colours red and green instead of the ones

used in the app

Contact same as phone

Some participants were confused that a Contact and a Phone icon

exist, as they thought it was the same thing

Updating contacts

outside of Easierphone

Participants noticed that updating contacts in the original contact app

outside of Easierphone it is not synchronized

Settings

Contact app naming

The "Contacts" tile naming (instead of e.g., “Address Book”) was

confusing for some participants

Easierphone: Participative Development of a Senior-Friendly Smartphone Application

203

Based on these feedbacks and inputs from the

participants, Pappy GmbH created a table based on

the raw data, which was then used as a foundation to

prioritize the issues and aligned all with the entire

team. A few issues have already been implemented in

the new version of the Easierphone app for testing in

pilot 2. Two examples of issues that have been

improved after the first testing are: a) WhatsApp, the

most frequently used app by the participants, is now

already integrated in Easierphone by default and does

not have to be added manually, and b) emergency

calls can now be triggered with one click. In the first

version, the emergency call required several clicks

which was considered too cumbersome by the

participants.

Referring to the main categories under section 4,

a few are illustrated in table 1. The main categories

were further subdivided into subcategories

concerning specific issues. For example, the category

of iii) Phone & Contacts was further split into, e.g.,

“accept phone call”, “contact same as phone” to

crystallize the problem and describe it more precisely

(see column “Issue description” of table 1). The

summarizing and categorizing of the diverse issues

helped to gain an overview and to find solutions to

improve the app.

4.3 Preliminary Findings from Pilot 2

As in pilot 1, participants like the idea, that navigation

on the smartphone is simplified by Easierphone app

as all significant apps are merged into one app and are

shown below each other on the Easierphone home

screen. Some were very pleased that they can see all

their apps sorted alphabetically when clicking on the

functionality “open other apps”. Most of the

participants are not aware that they could arrange

apps on their usual home screen to find them easier,

and that the alphabetically ordered list of all their apps

could be accessed via system settings anyway.

Through the testing process, participants

discovered new possibilities how they can use their

smartphones. This further shows the importance of an

initial instruction of the app (via a researcher, or

guided instruction by the app itself). At first glance,

most participants regard the app as easy to use, but

they still need instructions for all basic steps. Some

participants mentioned that the Easierphone app

would be most helpful for “newbies” who are only

starting to use a smartphone. If usage patterns with

the conventional home screen and conventional apps

are already present, the switch to Easierphone may be

irritating to some extent (e.g., because icons may look

different).

The meaning and use behind an integrated AI

module (providing a pedometer, recording mobility

patterns and apps being used) was not yet clear to

most the participants who have been interviewed so

far. However, we found that a few participants

already use a fitness tracker or a smartwatch (which

were not connected to their smartphones).

Explanation for this was, they would benefit more

from a tracking system they wear on the body while

being at home because their smartphones are placed

on a table or shelf, not tracking or recording anything.

The app installation process is largely determined

by the Android system requirements. Here,

Easierphone attempts to make the process as simple

as possible while complying to Android guidelines

(e.g., asking for various permissions directly on the

device). Our participants agreed to give all

permissions, but some were irritated by the quantity

of permissions they had to give during the installation

process. Asked about their feelings regarding online

privacy, most of them reply they have nothing to hide

anyway. Some participants reported that they

generally do not read the terms of use or privacy

settings in the digital world carefully. Nonetheless,

they still agree to them, so they are able to use an app

or a digital service. Another reason mentioned, was

that they are unwilling to invest too much time in

reading the terms of use, even though they think, they

should read the terms of use carefully.

5 DISCUSSION AND OUTLOOK

This study sets out to empower older adults to

effectively use a smartphone through a simple, clear

home screen and easy-to-use app for Android

smartphones. With the Easierphone app, the main

user can be remotely supported with the tandem

functionality which is simultaneously installed and

used by a family member, trusted friend, or

neighbour. Easierphone is conceived as an open and

expandable platform with the primary user’s screen

mirrored on the secondary user's device in the tandem

function.

So far, pilot 1 is completed and pilot 2 underway

with data collection. For an interim conclusion we can

state that Easierphone app is appealing to older

adults, providing an easy-to-use surface on their

smartphones. Overall, it was possible to get very

critical, detailed and thus helpful feedback from the

test participants in pilot 1. It was possible to integrate

many of their wishes and improvement inputs in the

further development of following versions of the app.

Simplifying smartphone usage and offering support

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

204

(remotely via a tandem option) was identified to be a

clear need of the participants.

Overall, participants appreciated the idea of a

simplification of using their smartphones very much.

The field tests over longer time periods shed light on

many interesting usability topics raised by the

participants. Nonetheless, the heterogeneity of the

participants in our study with a relatively small

sample size (N = 30) is high. There is great diversity

in usage habits and skills in handling smartphones.

While some of them try to solve problems by

themselves and as independently as possible, others

were found to be highly dependent on assistance

(tandem) and showed little self-confidence in

handling their devices. When it comes to support and

help with smartphone use, family, friends, and stores

of telecommunications providers play an important

role for older adults. Within this continuous

development the voices of older people must be heard

to understand their needs and overcome usability and

accessibility barriers. This inclusion refers to the goal

of overcoming the digital divide (Wang et al., 2011).

A clear limitation of this study is the relatively

small sample size (N = 30). Nonetheless, the aim of

the tests is not at all to be representative but mainly to

test through the app with end-users, find bugs in the

current versions of the app and to include further

wishes expressed by the participants. Unfortunately,

apart from Swiss-German participants, no potential

participants from another language region of

Switzerland were included. We strive for a balanced

participation of men and women, however, in pilot 1

only two men could be recruited as main testers of

Easierphone. In the current pilot 2, gender

distribution at this point of time is about fifty-fifty.

Furthermore, according to the socio-demographic

data, most of the participants are of higher

economical and educational background, as is often

the case with older adults volunteering to participate

in studies in general.

Another observation made by the IAF team is the

lack of well-established accessibility guidelines,

which could have been used already in the early

design stages of the Easierphone app. A range of

accessibility guidelines have been developed to

address the needs of vulnerable users (e.g., Web

Content Accessibility Guidelines; W3C, 2005)

Recommendations have been developed also for

smartphones and mobile apps (e.g., Darvishy et al.,

2021; Darvishy & Hutter, 2017). We believe these

should be considered in future development and

improvements of the Easierphone app to make it

more accessible, and attractive to end-users.

Regarding the issue of privacy and data

protection, participants conveyed feelings of

ambiguity. Participants showed a differentiation of

what they think they should (read terms of use

carefully) and what they actually do (just accept to

continue). This is an interesting observation we could

make during the tests and can be subsumed as privacy

paradox (Zeissig et al., 2017): Users know regarding

privacy they should be careful in the digital world, but

they resign to complexity of it and choose the easy

way The privacy paradox will be more thoroughly

examined in pilot 2 and 3. Currently it is being

discussed in the Easierphone project team if a

hardware solution (smartphones with Easierphone

pre-installed) might be a simpler way to set up and

bypass terms of use for an end-user as all permissions

could be set up by the programmers. However, this

option was not (yet) implemented for the current

project.

Continued efforts are made by the Easierphone

project team to make smartphones more accessible to

older adults and other vulnerable people in our

society. As soon as Easierphone app finds a more

widespread use, a quantitative survey to further

improve the app could be conducted. Nonetheless, the

great heterogeneity of end-users needs to be kept in

mind for further development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the European AAL Programme for funding

this research project. We could not have undertaken

this journey without the older participants and their

tandem partners, whom we would like to extend our

sincere thanks for their openness, interest, and

valuable time in all interviews. Special thanks go to

Jana Friebe and Claudio Capaul for their transcription

work during pilot 2.

REFERENCES

Awan, M., Ali, S., Ali, M., Abrar, M. F., Ullah, H., & Khan,

D. (2021). Usability Barriers for Elderly Users in

Smartphone App Usage: An Analytical Hierarchical

Process-Based Prioritization. Scientific Programming,

2021, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2780257

Blažič, B. J., & Blažič, A. J. (2020). Overcoming the digital

divide with a modern approach to learning digital skills

for the elderly adults. Education and Information

Technologies, 25(1), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s10639-019-09961-9

Easierphone: Participative Development of a Senior-Friendly Smartphone Application

205

Castells, M. (2011). The rise of the network society (2. ed.

with a new preface, [reprint]. The information age /

Manuel Castells: Vol. 1. Wiley-Blackwell.

Chen, K., & Chan, A. H. S [Alan Hoi Shou] (2014).

Gerontechnology acceptance by elderly Hong Kong

Chinese: A senior technology acceptance model

(STAM). Ergonomics, 57(5), 635–652. https://doi.org/

10.1080/00140139.2014.895855

Chen, K., & Chan, A. H. (2014). Predictors of

gerontechnology acceptance by older Hong Kong

Chinese. Technovation, 34(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.technovation.2013.09.010

Darvishy, A., & Hutter, H.P. (2017). Recommendations

for Age-Appropriate Mobile Application Design.

Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 242,

676–686.

Darvishy, A., Hutter, H.P., & Seifert, A. (2021).

Altersgerechte digitale Kanäle. Springer Fachmedien

Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-35501-2

Eurostat. (2018). Trust, security and privacy - smartphones

(2018). https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/3tx8cgjiik

8rsmro4igorw?locale=en

Fernández-Ardèvol, M., Rosales, A., Loos, E., Peine, A.,

Beneito-Montagut, R., Blanche, D., Fischer, B., Katz,

S., & Östlund, B. (2019). Methodological Strategies to

Understand Smartphone Practices for Social

Connectedness in Later Life. In J. Zhou & G. Salvendy

(Eds.), Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Human

Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Social Media,

Games and Assistive Environments (Vol. 11593, pp.

46–64). Springer International Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22015-0_4

Francis, J., Ball, C., Kadylak, T., & Cotten, S. R. (2019).

Aging in the Digital Age: Conceptualizing Technology

Adoption and Digital Inequalities. In B. B. Neves & F.

Vetere (Eds.), Ageing and Digital Technology (pp. 35–

49). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-

981-13-3693-5_3

Friemel, T. N. (2016). The digital divide has grown old:

Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New

Media & Society, 18(2), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.11

77/1461444814538648

Greenhalgh, T., Jackson, C., Shaw, S., & Janamian, T.

(2016). Achieving Research Impact Through Co-

creation in Community-Based Health Services:

Literature Review and Case Study. The Milbank

Quarterly, 94(2), 392–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/14

68-0009.12197

Guo, X., Sun, Y., Wang, N., Peng, Z., & Yan, Z. (2013).

The dark side of elderly acceptance of preventive

mobile health services in China. Electronic Markets,

23(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-012-

0112-4

Hedtke-Becker, A., Hoevels, R., Otto, U., Stumpp, G., &

Beck, S. (2012). Zu Hause wohnen wollen bis zuletzt.

In S. Pohlmann (Ed.),

Altern mit Zukunft (pp. 141–176).

VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.

1007/978-3-531-19418-9_6

Ma, Q., Chan, A. H. S [Alan H. S.], & Chen, K. (2016).

Personal and other factors affecting acceptance of

smartphone technology by older Chinese adults.

Applied Ergonomics, 54, 62–71. https://doi.org/10.10

16/j.apergo.2015.11.015

Marek, K. D., & Rantz, M. J. (2000). Aging in Place: A

New Model for Long-Term Care. Nursing

Administration Quarterly, 24(3), 1–11.

Misoch, S. (2019). Qualitative Interviews. De Gruyter.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110545982

Neves, B. B., & Vetere, F. (Eds.). (2019). Ageing and

Digital Technology. Springer Singapore.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3693-5

Pani-Harreman, K. E., Bours, G. J. J. W., Zander, I.,

Kempen, G. I. J. M., & van Duren, J. M. A. (2021).

Definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in

place’: a scoping review. Ageing and Society, 41(9),

2026–2059. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X2000

0094

Petrovčič, A., Slavec, A., & Dolničar, V. (2018). The Ten

Shades of Silver: Segmentation of Older Adults in the

Mobile Phone Market. International Journal of

Human–Computer Interaction, 34(9), 845–860.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2017.1399328

Pew Research Center. (2019). Smartphone Ownership Is

Growing Rapidly Around the World, but Not Always

Equally. https://www.pewglobal.org/wp-content/up

loads/sites/2/2019/02/Pew-Research-Center_Global-

Technology-Use-2018_2019-02-05.pdf

Piper, A. M., Garcia, R. C., & Brewer, R. N. (2016).

Understanding the Challenges and Opportunities of

Smart Mobile Devices among the Oldest Old.

International Journal of Mobile Human Computer

Interaction, 8(2), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.4018/

IJMHCI.2016040105

Reisdorf, B., & Rhinesmith, C. (2020). Digital Inclusion as

a Core Component of Social Inclusion. Social Inclusion,

2, 132–137.

Remmers, H. (2019). Pflege und Technik. Stand der

Diskussion und zentrale ethische Fragen. Ethik in Der

Medizin, 31(4), 407–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00

481-019-00545-2

Rößing, A. (2007). Senioren als Zielgruppe des Handels:

Status Quo und Perspektiven für ein demographisch

wachsendes Segment (1. Auflage). Wirtschaft.

Diplom.de.

Seifert, A., Ackermann, T. P., & Schelling, H. R. (2020).

Digitale Senioren 2020: Nutzung von Informations-

und Kommunikationstechnologien durch Personen ab

65 Jahren in der Schweiz. Universität Zürich; Pro

Senectute Schweiz.

Seifert, A., & Charness, N. (2022). Digital transformation

of everyday lives of older Swiss adults: Use of and

attitudes toward current and future digital services.

European Journal of Ageing, 19(3), 729–739.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00677-9

Seifert, A., Martin, M., & Perrig-Chiello, P. (2021).

Bildungs- und Lernbedürfnisse im Alter: Bericht zur

nationalen Befragungsstudie in der Schweiz.

Schweizerischer Verband der Seniorenuniversitäten

(U3).

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

206

Seifert, A., & Rössel, J. (2019). Digital Participation. In D.

Gu & M. E. Dupre (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Gerontology

and Population Aging (pp. 1–5). Springer International

Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69892-

2_1017-1

Siren, A., & Knudsen, S. G. (2017). Older Adults and

Emerging Digital Service Delivery: A Mixed Methods

Study on Information and Communications

Technology Use, Skills, and Attitudes. Journal of

Aging & Social Policy, 29(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/

10.1080/08959420.2016.1187036

Tsai, H.Y. S., Shillair, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2017). Social

Support and "Playing Around": An Examination of

How Older Adults Acquire Digital Literacy With

Tablet Computers. Journal of Applied Gerontology :

The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological

Society, 36(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/073346

4815609440

Tullis, T., & Albert, B. (2013). Measuring the user

experience: Collecting, analyzing, and presenting

usability metrics (Second edition). Elsevier/Morgan

Kaufmann.

UNDESA. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022:

Summary of Results. New York.

Unterstell, R. (2007). Die neuen Alten kommen. Forschung,

32(3), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/fors.200790024

W3C. (2005). Introduction to Web Accessibility. Web

Accessibility Initiative (WAI). https://www.w3.org/

WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-intro

Wang, F., Lockee, B. B., & Burton, J. K. (2011). Computer

Game-Based Learning: Perceptions and Experiences of

Senior Chinese Adults. Journal of Educational

Technology Systems, 40(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/

10.2190/ET.40.1.e

Xue, L., Yen, C. C., Chang, L., Chan, H. C., Tai, B. C., Tan,

S. B., Duh, H. B. L., & Choolani, M. (2012). An

exploratory study of ageing women's perception on

access to health informatics via a mobile phone-based

intervention. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 81(9), 637–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.ijmedinf.2012.04.008

Zeissig, E.M., Lidynia, C., Vervier, L., Gadeib, A., &

Ziefle, M. (2017). Online Privacy Perceptions of Older

Adults. In J. Zhou & G. Salvendy (Eds.), Lecture Notes

in Computer Science. Human Aspects of IT for the Aged

Population. Applications, Services and Contexts (Vol.

10298, pp. 181–200). Springer International Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58536-9_16

Zhou, J., Rau, P.L. P., & Salvendy, G. (2013). A

Qualitative Study of Older Adults’ Acceptance of New

Functions on Smart Phones and Tablets. In D.

Hutchison, T. Kanade, J. Kittler, J. M. Kleinberg, F.

Mattern, J. C. Mitchell, M. Naor, O. Nierstrasz, C.

Pandu Rangan, B. Steffen, M. Sudan, D. Terzopoulos,

D. Tygar, M. Y. Vardi, G. Weikum, & P. L. P. Rau

(Eds.), Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cross-

Cultural Design. Methods, Practice, and Case Studies

(Vol. 8023, pp. 525–534). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39143-9_59

Easierphone: Participative Development of a Senior-Friendly Smartphone Application

207