L2 Vocabulary Learning Benefits from Skill-Based Learner Models

Josh Ring, Frank Leon

´

e and Ton Dijkstra

Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Keywords:

CALL, L2 Vocabulary Learning, Learner Modeling.

Abstract:

Psycholinguistic research has established that words interact within the mental lexicon during both processing

and learning. In spite of this, many Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) systems treat second

language (L2) vocabulary learning as the memorization of “vocabulary facts”, and employ spaced-repetition

algorithms designed to optimize the formation and maintenance of individual memory traces. The Knowledge-

Learning-Instruction (KLI) framework provides guidelines as to what kind of knowledge components involve

which learning processes, and how they are best taught. We reconsider the position of L2 vocabulary learning

in the KLI framework, in light of extensive evidence of interaction and transfer effects in L2 vocabulary

learning. We argue that L2 vocabulary learning involves the acquisition of generalisable skills. We further

validate this claim with evidence from research into novel approaches to L2 vocabulary teaching. These novel

approaches align with the instructional recommendations made by the KLI framework for teaching complex

rules, not facts, yet they yield significant improvements in L2 vocabulary acquisition. Finally, on the basis

of these findings, we advocate for the use of skill-based learner models in order to optimize L2 vocabulary

learning in CALL applications.

1 INTRODUCTION

Learning a new word is a complex affair involving

diverse cognitive processes; we focus here specifi-

cally on L2 vocabulary learning. We assume that the

semantic form of the word is already established in

the learner’s mind, and we refer to L2 vocabulary

learning as the process by which an association is

made from the established semantic and phonologi-

cal/orthographic forms of a native (L1) word, to the

novel phonological/orthographic form of the corre-

sponding L2 word.

The primary goals of the present work are 1) to

demonstrate that L2 vocabulary learning involves the

acquisition of generalisable skills; and 2) to advo-

cate for the use of skill-based models of L2 vocab-

ulary learning in computer-assisted language learning

(CALL) applications.

The past decade has seen a marked rise in both the

supply of and the demand for CALL applications both

inside and outside the classroom. A key advantage of

CALL applications is their ability to track learners’

progress and present the appropriate material at the

appropriate time. This adaptive behaviour is driven by

a learner model, which infers a learner’s knowledge

state on the basis of their interactions with the CALL

application. In the following, we distinguish between

memory-based and skill-based learner models.

1.1 Memory vs. Skill-Based Models of

L2 Vocabulary Learning

Memory-based learner models are underpinned by

decades of research, from the forgetting curves first

reported by (Ebbinghaus, 1913), to the oft-replicated

spacing and testing effects (Cepeda et al., 2006;

Karpicke, 2017). In perhaps the most widely ac-

cepted mathematical model of these effects, (Pavlik

and Anderson, 2005) used the exponential decay of

memories in the ACT-R cognitive modelling frame-

work to simulate the (un)successful acquisition of L2

Japanese vocabulary by L1 English speakers. (Pavlik

and Anderson, 2008) subsequently used this learner

model to derive an algorithm which adapts the pre-

sentation schedule of L1↔L2 word pairs so as to

optimize the formation and maintenance of individ-

ual memory traces, accelerating learning and improv-

ing retention. Such spaced repetition algorithms have

since been successfully integrated into CALL sys-

tems, where they are used to adapt the order of vocab-

ulary items based on learners’ performance, yielding

meaningful improvements in L2 vocabulary learning

322

Ring, J., Leoné, F. and Dijkstra, T.

L2 Vocabulary Learning Benefits from Skill-Based Learner Models.

DOI: 10.5220/0011981800003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 1, pages 322-329

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

(Belardi et al., 2021).

Skill-based models, in contrast, assume that learn-

ers acquire a compendium of latent skills. Different

tasks involve different (sets of) skills, and a learner’s

performance depends on the degree of overlap be-

tween the skills they possess and the skills involved

in the task. The theoretical basis for these models

is provided by the Knowledge-Learning-Instruction

(KLI) framework, which we return to later. Some au-

thors argue that skill-based learner models are unsuit-

able for modeling L2 vocabulary learning (Pel

´

anek,

2017; Choffin et al., 2019). The rationale is that L2

vocabulary learning involves the memorization of in-

dependent “vocabulary facts”, rather than the acquisi-

tion and application of generalisable skills. This is in

spite of considerable evidence that learners generalize

familiar sound and spelling patterns to novel vocabu-

lary.

In the following, we briefly summarize the KLI

framework, and how it relates to L2 vocabulary learn-

ing. In Section 2, we present substantial evidence

from psycholinguistics research that learner’s transfer

knowledge from known to novel vocabulary. In Sec-

tion 3, we argue that learning involves the acquisition

of generalisable skills, and relies on more complex

learning processes than simple fact memorization. We

present evidence from the literature that the instruc-

tional methods recommended by the KLI framework

for stimulating these complex learning processes are

effective for L2 vocabulary instruction, and we ex-

plore the implications of these instructional methods

for CALL-based vocabulary instruction.

1.2 The Knowledge-Learning-

Instruction Framework

We present a brief overview of the main elements

of the KLI framework in the following, focussing

on those elements that are relevant to our argument.

Then, we critically examine where L2 vocabulary

learning is positioned in the framework. For an in-

depth treatment of the KLI framework, the interested

reader is referred to (Koedinger et al., 2012).

1.2.1 Knowledge Components

The KLI framework defines a knowledge component

(KC) as “an acquired unit of cognitive function or

structure”, a broad generalization across such diverse

terms as “production rule, schema, misconception, or

facet, as well as everyday terms such as concept, fact,

or skill” (Koedinger et al., 2012). In order to distin-

guish these diverse terms, KCs are categorized into a

taxonomy according to several criteria. The primary

distinction involves application and response condi-

tions, which can both be either constant or variable.

A constant-constant KC, otherwise known as a

fact or association, has both constant application and

constant response conditions. For example, when

asked to recite the equation for calculating the area

of a circle (constant application), the correct answer

is always A = πr

2

(constant response).

A variable-variable KC, otherwise known as a

rule or skill, has both variable application and vari-

able response conditions, and is applied to a variety

of situations in a context-sensitive manner. For ex-

ample, the rule for generating the past-tense of regu-

lar English verbs by appending the suffix -ed applies

to multiple verbs (variable application), and produces

a different response depending on the verb being in-

flected (variable response).

The KLI framework goes on to argue that these

different kinds of KCs involve different learning pro-

cesses, and are thus best instructed in different ways,

as follows.

1.2.2 Learning Processes

Having established various categories of KCs, the

KLI framework then defines a hierarchy of learning

processes, ordered by increasing complexity. The

simplest set of learning processes are denoted mem-

ory and fluency building processes. As the name sug-

gests, they involve the formation and reinforcement of

memories, retrieval of which becomes faster and more

fluent as the frequency of exposure increases. These

processes are most relevant for constant-constant

KCs, which need to be practiced until they are mem-

orized.

Slightly more complex are induction and re-

finement processes, which encompass generalization,

discrimination, categorization, and rule induction

(Koedinger et al., 2012). These processes are in-

volved in specifying and refining the application con-

ditions of variable-variable KCs, by adding missing

conditions or removing irrelevant conditions. For ex-

ample, a student of English might initially induce that

the -ed suffix produces the past tense of all English

verbs, and only arrive at the correct KC with addi-

tional refinement.

Notably, each class of learning processes is not

typically restricted to a single kind of KC, however,

not all processes are relevant for all KCs. Mem-

ory and fluency building processes are relevant at all

stages of learning for all kinds of KCs, because both

arbitrary paired-associates (constant-constant KCs)

and scientific principles (variable-variable KCs) can

equally be forgotten if not practiced. Induction and

refinement processes, however, may not be relevant

L2 Vocabulary Learning Benefits from Skill-Based Learner Models

323

for paired-associates, for which there exists no under-

lying rule or pattern which must be induced.

1.2.3 Instructional Methods

The KLI framework further posits that the kinds of

learning processes involved in the acquisition of a KC

determines how that KC is best taught. For constant-

constant KCs involving memory and fluency build-

ing processes, the KLI framework recommends using

spaced repetition, a class of methods that space repe-

titions of a KC in order to optimize the formation and

maintenance of individual memory traces, often used

in conjunction with (digital) flashcards.

For variable-variable KCs involving induction and

refinement processes, the KLI framework recom-

mends feature focussing, or drawing the learner’s at-

tention to key features of the material to be learned.

We examine this instruction method more closely

later in the text. Additional instructional recommen-

dations are presented and discussed in (Koedinger

et al., 2012).

By defining a dependency chain from KC type,

to learning process, to instructional method, the KLI

framework explicitly acknowledges that how a par-

ticular subject matter is conceptualized plays a ma-

jor role in how this subject matter is taught. It fol-

lows that an inaccurate conceptualization would lead

to the application of inefficient instructional methods

(where efficiency refers to achieving as much learning

as possible in as little time as possible), or to the pre-

mature dismissal of suitable but unproven methods.

As such, it is of crucial importance to regularly assess

a particular subject matter’s KC conceptualization in

light of new evidence. In the following, we critically

examine the position of L2 vocabulary learning in the

taxonomy presented by the KLI framework.

1.3 Vocabulary Learning in the KLI

Framework

Several examples of various kinds of KCs found in

different fields are provided in Table 2 of (Koedinger

et al., 2012). The first example, which presents an L2

vocabulary item as an example of a constant-constant

KC, illustrates what we believe is a common mis-

conception in both the psychology literature, where

L1↔L2 word pairs serve as stand-ins for arbitrary

paired-associates e.g. (Pavlik and Anderson, 2005),

and in CALL applications which aim to optimize L2

vocabulary learning by optimizing independent mem-

ory traces for each word, namely: that vocabulary

learning involves purely constant-constant KCs and is

thus akin to paired-associate or fact learning, whereby

independent “vocabulary facts” need simply be mem-

orized.

This conceptualization has implications for how

L2 vocabulary is approached in CALL applications.

By conceptualizing vocabulary items as constant-

constant KCs, CALL applications restrict themselves

to instructional methods that optimize fluency and

memory building processes i.e. spaced repetition, as

per the KLI framework.

The authors of the KLI framework acknowledge

that not all vocabulary KCs are constant-constant.

They point out that words with explicit morphological

markers, such as the -ed suffix in jumped, are more ac-

curately described by a variable-variable KC, i.e. the

past-tense derivation rule for regular English verbs.

They also point out that many Mandarin characters

are composed of recurring components, so-called rad-

icals, and argue that such knowledge is also best de-

scribed as variable-variable KCs, i.e. the rules defin-

ing how radicals affect meaning in the contexts of dif-

ferent compound characters.

While these examples are presented as exceptions

to the otherwise constant-constant nature of vocabu-

lary learning, we argue that these are not exceptions

at all, but the rule. In contradiction to the constant-

constant, paired-associate conceptualization of L2 vo-

cabulary learning adopted in the KLI framework and

many CALL applications, there is significant evi-

dence that knowledge transfers from known to novel

words during learning. We review the empirical evi-

dence of these interactions in the following.

2 VOCABULARY PAIRS ARE

NOT INDEPENDENT FACTS

Psycholinguists have spent decades examining how

words interact during processing, production, and

learning. These interactions mean that not all words

are equally difficult to learn. Rather, the difficulty

of learning an L2 word is a function of both the L1

and L2 words already known, as well as the other L2

words currently being learned. This is summarized

succinctly by Nation’s concept of learning burden,

described as follows:

The general principle of learning burden (Na-

tion, 1990) is that the more a word represents

patterns and knowledge that the learners are

already familiar with, the lighter its learning

burden. These patterns and knowledge can

come from the first language, from knowledge

of other languages, and from previous knowl-

edge of the second language. (Nation, 2001)

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

324

A word’s learning burden is determined by how

similar it is to other words; this similarity is gener-

ally expressed in terms of wordlikeness. Wordlikeness

measures how closely a particular word adheres to the

phonological and orthographic regularities of a par-

ticular language, and is operationalized by phonotac-

tic or orthotactic probability, and neighborhood den-

sity. Phonotactic and orthotactic probability measure

the probability of observing the sequence of sounds or

letters, respectively, that make up a particular word in

a particular language. For example, dobrze, the Pol-

ish word for good, has an extremely low orthotactic

probability in English, due to the orthographically il-

legal <brz> letter-trigram. When computed against

the rest of the Polish language, however, the orthotac-

tic probability of dobrze is much higher. Neighbor-

hood density, meanwhile, refers to how many words

differ from a particular word in only a few sounds

or letters. For example, bake has many close ortho-

graphic neighbors (make, bike, bare etc.), and thus

resides in a dense orthographic neighborhood.

Wordlikeness can be seen as a measure of how

similar a particular word is to an entire language.

When evaluating this similarity, the choice of which

language to compare against is key. The wordlikeness

of new L2 vocabulary is typically evaluated relative to

the learner’s L1 (or rather, a corpus representative of

the L1), and a novel L2 word’s L1 wordlikeness has

been shown to affect its learning burden. This indi-

cates that novel L2 words interact with the learner’s

established L1 lexicon.

However, the wordlikeness of new L2 vocabulary

can also be evaluated relative to the L2 vocabulary al-

ready acquired, as in the dobrze example. A novel L2

word’s L2 wordlikeness has also been found to affect

learning burden, indicating that novel L2 words also

interact with the learner’s developing L2 lexicon. We

review the extensive body of research on L1 and L2

wordlikeness in the following.

2.1 Interactions Between L2

Vocabulary and the L1 Lexicon

The earliest investigation into interactions between

L2 vocabulary and the L1 lexicon was performed by

(Ellis and Beaton, 1993), who examined the effects

of several word form characteristics on vocabulary

learning under various conditions. Most interesting

for our present purposes are the effects of phonotactic

regularity and minimum bigram frequency (the fre-

quency of the least common bigram in the word), op-

erationalizations of phonotactic and orthotactic prob-

ability, respectively. Both phonotactic regularity and

minimum bigram frequency were positively corre-

lated with L1→L2 translation accuracy across all

learning conditions (Ellis and Beaton, 1993).

A similar effect was observed by (Storkel et al.,

2006), who investigated the distinct effects of phono-

tactic probability and neighborhood density on adult

pseudo-word learning. While not the first to in-

vestigate these variables, (Storkel et al., 2006) were

the first to manipulate each while controlling the

other. Prior studies had either intentionally manipu-

lated both, or manipulated one while not controlling

for the other, as in (Ellis and Beaton, 1993). This in-

troduces a confound, as the variables are correlated: a

word with many neighbors will by definition contain

common letter or sound pairs, due to overlap with its

many neighbors. (Storkel et al., 2006) exposed adults

to 16 pseudo-words referring to novel objects in a

story context. Pseudo-words varied in both phono-

tactic probability and neighborhood density, falling

into one of four categories: high-probability/high-

density, high/low, low/high, and low/low. Learn-

ing performance was evaluated during training us-

ing a picture naming task, in which participants were

shown an item and asked to speak the correspond-

ing pseudo-word. (Storkel et al., 2006) combined

and analysed partially correct (2/3 phonemes correct)

and fully correct responses, finding that participants

made fewer mistakes when producing low-probability

pseudo-words (low probability advantage), and when

producing high-density pseudo-words (high density

advantage).

These findings were replicated in preschool chil-

dren by (Storkel and Lee, 2011), who observed low-

probability and high-density advantages for preschool

children learning pseudo-words paired with novel ob-

jects across two experiments. Stimuli in the first ex-

periment varied in phonotactic probability, but were

held constant in neighborhood density; and vice-versa

in the second experiment. Learning in both exper-

iments was assessed using a referent-identification

task, in which participants heard a pseudo-word and

had to identify the corresponding object.

Building on prior work examining the effect of

phonological wordlikeness on L2 or pseudo-word

learning, (Bartolotti and Marian, 2017b) investigated

the effect of orthographic wordlikeness. Participants

were tasked with learning 48 pseudo-words paired

with images of common objects, such as a pear or

a tent. Pseudo-word stimuli were split into two cat-

egories of high and low wordlikeness, with high-

wordlikeness stimuli exhibiting both high orthotac-

tic probability and high neighborhood density relative

to participants’ L1. Learning was assessed in recog-

nition and production tasks, both revealing a high-

wordlikeness facilitation effect. Similar results were

L2 Vocabulary Learning Benefits from Skill-Based Learner Models

325

obtained by (Bartolotti and Marian, 2017a), who used

the same stimuli and procedure to examine the ef-

fect of wordlikeness on pseudo-word learning in En-

glish/German bilinguals. Stimuli were divided into

four categories: high English wordlikeness, high Ger-

man wordlikeness, high combined wordlikeness, and

low combined wordlikeness. Learning was again as-

sessed in recognition and production tasks identical

to those in (Bartolotti and Marian, 2017b), revealing

a high-wordlikeness facilitation effect for both tasks

across all three wordlike categories.

These results establish that L2 vocabulary inter-

act with the learner’s established L1 lexicon. They

demonstrate that an L2 word’s learning burden is de-

termined in part by how closely it adheres to the

phonological and orthographic regularities that an L1

speaker has grown accustomed to over a lifetime

of L1 exposure. There is, however, another source

of spelling and sound regularities that influence an

L2 word’s learning burden, namely the sound and

spelling regularities of the L2, which we will exam-

ine next.

2.2 Interactions Amongst L2

Vocabulary

Building on prior work investigating L1 wordlike-

ness, researchers began examining the role of word-

likeness of novel L2 vocabulary relative to the L2 be-

ing learned. This idea was (to our knowledge) first

explored explicitly by (Stamer and Vitevitch, 2012),

who examined the effect of L2 phonological neigh-

borhood density on the acquisition of novel L2 words.

Participants were intermediate learners of L2 Spanish,

and were exposed to novel Spanish words paired with

black & white line drawings. Neighborhood density

was computed against a corpus of ∼3900 words ob-

tained from a beginner Spanish textbook, with half

of the stimuli residing in sparse neighborhoods, and

half in dense neighborhoods. Learning was assessed

in production and recognition tasks, revealing a high-

density facilitation effect for both tasks.

Similar effects were observed by (Bartolotti and

Marian, 2017a; Bartolotti and Marian, 2017b), who

in addition to extending prior results on L1 phono-

logical wordlikeness to orthography, also discovered

evidence of pseudo-L2 interactions. When analyz-

ing participants’ incorrect responses, they found that

the positional letter frequency of the pseudo-language

(i.e. the set of pseudo-words used as stimuli in the ex-

periment) was a better predictor of spelling errors than

the positional letter frequencies of English, and, in

the case of (Bartolotti and Marian, 2017a), also Ger-

man. This indicates that participants’ production at-

tempts were informed by the statistics of their nascent

pseudo-L2 lexicon.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that

novel L2 words interact not only with learners’ es-

tablished L1 lexicons, but also with their develop-

ing L2 lexicons, during learning. These interactions

are present at the earliest stages of language learning,

and persist for intermediate L2 learners. All these

various interactions combine into a clear argument

against the constant-constant, paired-associates con-

ceptualization of L2 vocabulary learning underlying

the spaced-repetition algorithms commonly found in

CALL applications. We propose an alternative con-

ceptualization in the following.

3 VOCABULARY LEARNING AS

FUZZY RULE LEARNING

The empirical findings of the roles of L1 and L2 word-

likeness, and the effects of learning sets of similar

L2 words, demonstrate that L2 vocabulary learning is

not a matter of acquiring constant-constant KCs in the

form of independent vocabulary facts. In contrast, we

argue that (L2) vocabulary learning involves the ac-

quisition of variable-variable KCs without rationale,

namely spelling and sound rules. Learners generalize

these rules (for better or for worse) to other words and

other languages.

It must be noted that these variable-variable KCs

are not as explicit or discrete as the examples dis-

cussed in the context of the KLI framework. For ex-

ample, the rule for generating the past-tense of regular

English verbs can be explicitly defined as appending

the suffix -ed. This rule is binary: it applies equally to

all regular English verbs, and does not apply to irreg-

ular verbs.

Wordlikeness, in contrast, is not a binary distinc-

tion, and the rules that determine wordlikeness are

difficult to state explicitly. As such, the KCs involv-

ing the spelling and sound rules that underlie word-

likeness are implicit and fuzzy. Pseudo-words can be

more or less wordlike, with speakers ascribing vary-

ing degrees of wordlikeness to pseudo-words on a

continuous scale, depending on their proximity to the

L1 (Greenberg and Jenkins, 1964).

Rather than constant-constant KCs that are

learned via memory and fluency building processes,

L2 vocabulary learning involves variable-variable

KCs learned via induction and refinement processes.

Reconceptualizing L2 vocabulary learning in this

manner paves the way towards novel and poten-

tially more efficient methods of vocabulary instruc-

tion, which we examine in the following.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

326

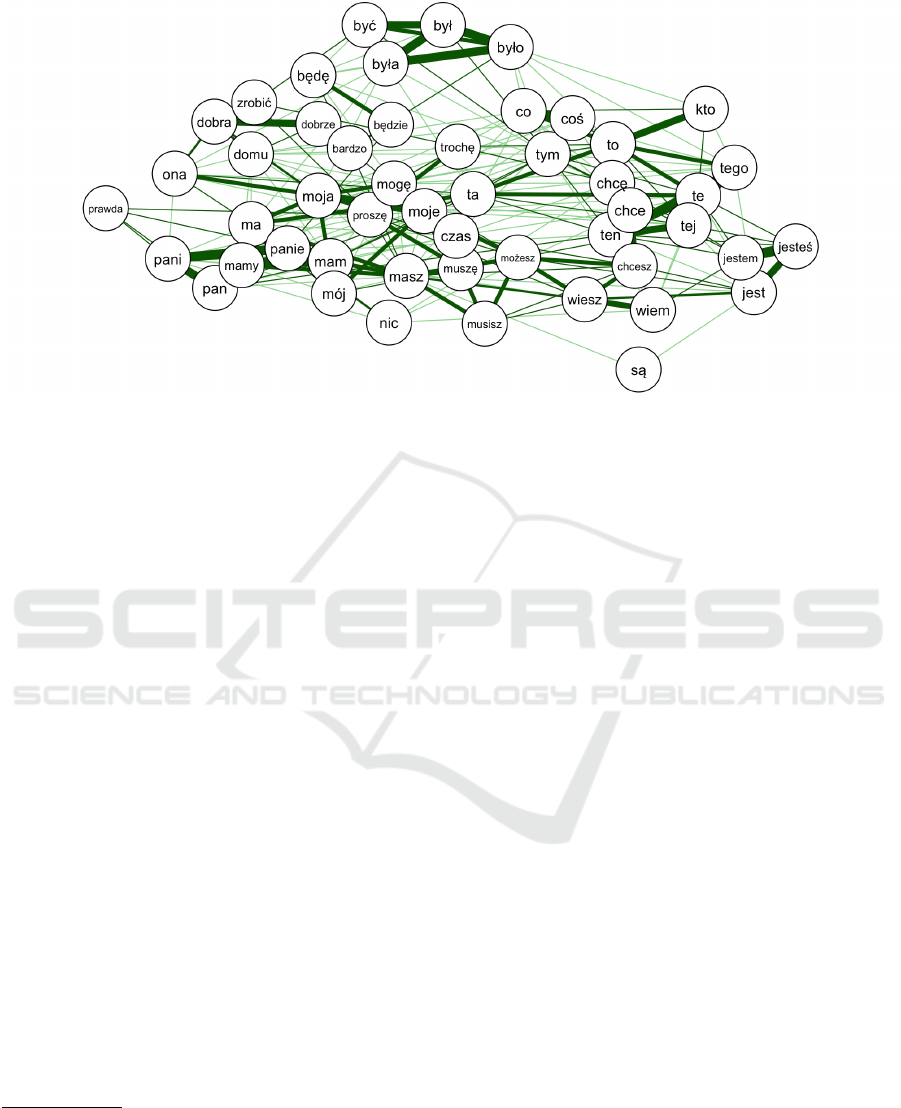

Figure 1: In contrast to independent “vocabulary facts”, L2 vocabulary share spelling and sound regularities which influence

learning, and which we argue CALL systems should take into account. Here, a visualization of the similarities between

common Polish words (measured in Levenshtein distance), analogous to the skill dependency graphs in Figure 4 of (Piech

et al., 2015).

3.1 Case Study: Feature Focussing

The KLI framework recommends different instruc-

tional methods for different types of KCs and their

associated learning processes. For variable-variable

KCs and induction and refinement processes, the

KLI framework recommends feature focussing, an in-

structional method whereby the learner’s attention is

drawn to relevant differences between items being

learned.

An example is provided in (Koedinger et al., 2012)

of applying this method to Chinese vocabulary learn-

ing.

1

Chinese characters are predominantly phono-

semantic compound characters, whereby one com-

ponent denotes the semantic association, while the

other(s) denotes the phonetic pronunciation. Re-

search has shown that instructing a learner to attend

to the semantic component of a compound character

facilitates acquisition of L2 Chinese vocabulary (Taft

and Chung, 1999).

Feature focussing has also been found to be ef-

fective when the learner’s attention is only implicitly

directed towards relevant features of the items being

learned (van de Ven et al., 2019; Baxter et al., 2021;

Baxter et al., 2022). Rather than providing their par-

ticipants with explicit instructions, these studies en-

1

In spite of presenting L2 Chinese vocabulary learning

as an example of the success of feature focussing, an in-

structional method designed to enhance induction and re-

finement processes involved in the acquisition of variable-

variable KCs, (Koedinger et al., 2012) otherwise repeatedly

insist on the constant-constant nature of L2 vocabulary ac-

quisition.

couraged implicit feature focussing by purposefully

presenting novel vocabulary alongside close phono-

logical, orthographic, or semantic neighbors.

(van de Ven et al., 2019) arranged L2↔image

pairs into triplets of phonologically similar L2 words

(e.g. mace, maze, and maid). A referent-identification

task required participants to listen to an L2 word

and select the corresponding image. In the fea-

ture focussing condition, distractor images were taken

from within a similarity triplet; in the control condi-

tion, distractor images were selected from dissimilar

triplets. Participants in the feature focussing condi-

tion outperformed the control condition in an imme-

diate post-test (van de Ven et al., 2019).

(Baxter et al., 2022) arranged L1↔pseudo-word

pairs into clusters of highly similar pseudo-words

(e.g. mion, nion, niol, tiol, and nioc). Participants

were presented an L1 word and tasked with select-

ing the corresponding pseudo-word. In the feature fo-

cussing condition, distractor pseudo-words were se-

lected from within the similarity cluster; in the con-

trol condition, distractors were selected from dissim-

ilar clusters. (Baxter et al., 2021) used a similar ex-

perimental design to examine feature focussing in L1

Dutch children learning L2 English words. In both

studies, participants in the feature focussing condition

committed more errors during training, but performed

better on immediate and late post-tests (Baxter et al.,

2021; Baxter et al., 2022).

The successful application of feature focussing –

a method designed to stimulate the induction and re-

finement learning processes – to L2 vocabulary in-

L2 Vocabulary Learning Benefits from Skill-Based Learner Models

327

struction is further evidence of the variable-variable

nature of L2 vocabulary KCs. A practical concern

regarding the use feature focussing in CALL applica-

tions is that the distractors must be carefully selected

so as to be sufficiently similar to the target. This re-

quirement is reasonable when working with pseudo-

words, but is much harder to satisfy when working

with natural L2 vocabulary.

Rather than employ feature focussing in CALL

applications directly, we advocate for the use of auto-

mated methods that capitalize on the variable-variable

nature of L2 vocabulary KCs. We explore such meth-

ods in the following.

3.2 Implications for CALL

Rejecting the constant-constant KC conceptualiza-

tion of L2 vocabulary learning does not amount to

rejecting the use of spaced repetition algorithms in

CALL applications. As argued by (Koedinger et al.,

2012), the memory and fluency processes addressed

by spaced repetition are equally vital to the acquisi-

tion of variable-variable KCs, which could otherwise

be forgotten. Rather, we argue that spaced repetition

should be used in combination with learner models

that are sensitive to the fuzzy, implicit skills involved

in L2 vocabulary learning, i.e. the recognition and

production of particular sound and spelling patterns.

A contemporary approach would be to apply deep

learning skill-based learner models to L2 vocabulary

learning. Such models have generally been designed

with discrete skills in mind, with each exercise falling

under one or more skill categories (Piech et al., 2015;

Pu et al., 2020). These models can, however, be mod-

ified to work with vector representations of L2 vocab-

ulary items that are sensitive to L1 and L2 wordlike-

ness, such as the bilingual orthographic embeddings

proposed by (Severini et al., 2020).

Such a model could detect and adapt to the unique

learning burden experienced by learners with differ-

ent backgrounds; for example, an English-speaking

learner of Polish might struggle with particular con-

sonant clusters that are illegal under English spelling,

whereas a Czech-speaking learner of Polish might

be familiar with those letter combinations, but strug-

gle with an entirely different set of spelling patterns.

CALL applications equipped with a learner model

that has access to the spelling and sound patterns of

the words being learned could adapt to this unique

behaviour, and recommend personalized vocabulary

lists tuned to the sound and spelling patterns that each

learner is familiar with, thus lightening the learning

burden.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The dependency chain from KC type, to learning

process, to instructional method defined by the KLI

framework makes explicit the fact that how we con-

ceptualize the KCs involved in a particular subject

matter has consequences for the instructional methods

we choose to employ. The “vocabulary fact” concep-

tualization of L2 vocabulary learning functions both

to justify the use of spaced repetition algorithms, as

well as to argue against the use of more complex,

skill-based student models in CALL applications.

On the basis of extensive evidence of interaction

and transfer effects in L2 vocabulary learning, and

evidence of the efficacy of L2 vocabulary instruction

methods tailored to variable-variable KC acquisition,

we argue that L2 vocabulary learners develop gener-

alisable skills, and advocate for the use of skill-based

learner models in CALL applications. While steps in

this direction have already been taken, e.g. (Zylich

and Lan, 2021), such approaches are still in the mi-

nority, and we hope that the theoretical justification

presented here will encourage others to contribute to

this effort.

REFERENCES

Bartolotti, J. and Marian, V. (2017a). Bilinguals’ existing

languages benefit vocabulary learning in a third lan-

guage. Language Learning, 67(1):110–140.

Bartolotti, J. and Marian, V. (2017b). Orthographic knowl-

edge and lexical form influence vocabulary learning.

Applied Psycholinguistics, 38(2):427–456.

Baxter, P., Bekkering, H., Dijkstra, T., Droop, M., van den

Hurk, M., and Leon

´

e, F. (2022). Contrasting ortho-

graphically similar words facilitates adult second lan-

guage vocabulary learning. Learning and Instruction,

80:101582.

Baxter, P., Droop, M., van den Hurk, M., Bekkering, H.,

Dijkstra, T., and Leon

´

e, F. (2021). Contrasting similar

words facilitates second language vocabulary learn-

ing in children by sharpening lexical representations.

Frontiers in Psychology, 12:688160.

Belardi, A., Pedrett, S., Rothen, N., and Reber, T. P.

(2021). Spacing, feedback, and testing boost vocabu-

lary learning in a web application. Frontiers in Psy-

chology, 12.

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., and Rohrer,

D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks:

A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological

Bulletin, 132(3):354–380.

Choffin, B., Popineau, F., Bourda, Y., and Vie, J.-J. (2019).

DAS3H: Modeling student learning and forgetting

for optimally scheduling distributed practice of skills.

arXiv:1905.06873.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

328

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). Memory: A contribution to exper-

imental psychology (translated by Henry A. Ruger &

Clara E. Bussenius; original German work published

1885). Teachers College, Columbia University.

Ellis, N. C. and Beaton, A. (1993). Psycholinguistic de-

terminants of foreign language vocabulary learning.

Language Learning, 43(4):559–617.

Greenberg, J. H. and Jenkins, J. J. (1964). Studies in the

psychological correlates of the sound system of Amer-

ican English. WORD, 20(2):157–177.

Karpicke, J. D. (2017). Retrieval-based learning: A decade

of progress. In Byrne, J. H., editor, Learning and

Memory: A Comprehensive Reference (Second Edi-

tion), pages 487–514. Academic Press, Oxford.

Koedinger, K. R., Corbett, A. T., and Perfetti, C.

(2012). The knowledge-learning-instruction frame-

work: Bridging the science-practice chasm to en-

hance robust student learning. Cognitive Science,

36(5):757–798.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another

Language. Cambridge Applied Linguistics. Cam-

bridge University Press, Cambridge.

Pavlik, P. I. and Anderson, J. R. (2005). Practice and for-

getting effects on vocabulary memory: An activation-

based model of the spacing effect. Cognitive Science,

29(4):559–586.

Pavlik, P. I. and Anderson, J. R. (2008). Using a model to

compute the optimal schedule of practice. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Applied, 14(2):101–117.

Pel

´

anek, R. (2017). Bayesian knowledge tracing, logistic

models, and beyond: An overview of learner mod-

eling techniques. User Modeling and User-Adapted

Interaction, 27(3):313–350.

Piech, C., Bassen, J., Huang, J., Ganguli, S., Sahami, M.,

Guibas, L. J., and Sohl-Dickstein, J. (2015). Deep

knowledge tracing. In Advances in Neural Informa-

tion Processing Systems, volume 28. Curran Asso-

ciates, Inc.

Pu, S., Yudelson, M., Ou, L., and Huang, Y. (2020). Deep

knowledge tracing with transformers. In Bittencourt,

I. I., Cukurova, M., Muldner, K., Luckin, R., and

Mill

´

an, E., editors, Artificial Intelligence in Educa-

tion, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 252–

256, Cham. Springer International Publishing.

Severini, S., Hangya, V., Fraser, A., and Sch

¨

utze, H.

(2020). Combining word embeddings with bilingual

orthography embeddings for bilingual dictionary in-

duction. In Proceedings of the 28th International Con-

ference on Computational Linguistics, pages 6044–

6055, Barcelona, Spain (Online). International Com-

mittee on Computational Linguistics.

Stamer, M. K. and Vitevitch, M. S. (2012). Phonological

similarity influences word learning in adults learning

Spanish as a foreign language*. Bilingualism: Lan-

guage and Cognition, 15(3):490–502.

Storkel, H. L., Armbr

¨

uster, J., and Hogan, T. P. (2006). Dif-

ferentiating phonotactic probability and neighborhood

density in adult word learning. Journal of Speech,

Language, and Hearing Research, 49(6):1175–1192.

Storkel, H. L. and Lee, S.-Y. (2011). The independent ef-

fects of phonotactic probability and neighbourhood

density on lexical acquisition by preschool children.

Language and Cognitive Processes, 26(2):191–211.

Taft, M. and Chung, K. (1999). Using radicals in teaching

Chinese characters to second language learners. Psy-

chologia: An International Journal of Psychology in

the Orient, 42:243–251.

van de Ven, M., Segers, E., and Verhoeven, L. (2019). En-

hanced second language vocabulary learning through

phonological specificity training in adolescents. Lan-

guage Learning, 69:222–250.

Zylich, B. and Lan, A. (2021). Linguistic skill modeling for

second language acquisition. In LAK21: 11th Inter-

national Learning Analytics and Knowledge Confer-

ence, LAK21, pages 141–150, New York, NY, USA.

Association for Computing Machinery.

L2 Vocabulary Learning Benefits from Skill-Based Learner Models

329