Using Knowledge Maps to Create a Business School Faculty Portrait

Tatiana Gavrilova

1a

, Dmitry Kudryavtsev

2b

and Olga Alkanova

1c

1

Graduate School of Management, St. Petersburg University, Saint-Petersburg, Russia

2

Digital City Planner Oy, Helsinki, Finland

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Knowledge Maps, Competency Maps, Business School Education,

Higher Education.

Abstract: The primary university faculty activities are Teaching, Research, Applied practice (e.g. consulting), and

Professional Service (including administrative activities). It often happens that the scope and specifics of

faculty competencies and expertise are not well understood by colleagues within their university or outside.

This paper presents a new approach for mapping faculty competencies in universities, focusing on three

dimensions (3D): research, teaching, and applied practice. The approach was demonstrated at a business

school, which is a part of a large university. The need for the knowledge map there was driven by the

development of the new school strategy and the demand for more intense industry-university collaboration.

The survey method was applied for data collection and involved 63 faculty members. The data about the

faculty’s expertise was structured using predefined subject areas and presented in the form of digital

knowledge maps. These maps represent areas of expertise, including well-developed and underdeveloped

areas, providing a comprehensive overview of faculty capabilities. The suggested approach gives universities

an opportunity to create such knowledge maps for evidence-based talent and knowledge management.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the growing complexity of all processes and

products in the rapidly changing environment, it is

becoming crucial to manage knowledge assets with

their locations and owners. This is essential both for

individuals to be able to solve challenging problems

and increase personal effectiveness and for

organizations to gain a competitive advantage and

mitigate risks caused by the concentration of

knowledge among several experts. Universities are

great knowledge hubs where faculty members

communicate with students, do research in their

narrow fields, and collaborate with companies that

order consulting services. In all three cases, the

faculty member's professional profile and expertise

remain closed to an outside observer. Even within the

department, it might not be known about each

employee’s activities. The same thing happens at the

scale of institutes and universities.

The purpose of this paper is to discuss the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1466-8100

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1798-5809

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2530-6765

methodology for constructing knowledge maps that

create the possibility to visualize both professional

personal portraits of the faculty members and a

generalized knowledge portrait of a university unit

using the case of a university business school.

The general idea behind the proposed method is

to capture various areas of faculty activity through

precise categorization and map it towards the

knowledge fields. Based on international practice in

higher education, we suggest the following three

activity categories to be addressed: teaching,

research, and applied practice. Whereas the first two

are relatively clear, the third one implies all faculty

member's activities that relate to the practical

(industrial) application of their knowledge. This third

area may include anything from consulting to part-

time jobs in the private sector or elsewhere.

Knowledge mapping is a powerful method of

information visualization that enables society or

companies to connect experts, access knowledge in

time, identify knowledge assets and flow, and identify

Gavrilova, T., Kudryavtsev, D. and Alkanova, O.

Using Knowledge Maps to Create a Business School Faculty Portrait.

DOI: 10.5220/0012181000003598

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2023) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 185-193

ISBN: 978-989-758-671-2; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright © 2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

185

existing knowledge resources and knowledge gaps

(Faisal et al., 2019).

This paper suggests that a combination of

quantitative and qualitative analysis methods can

capture different aspects of expertise and create

digital knowledge maps, that can provide rich

navigation for understanding the multitude of faculty’

intellectual potential. We also discuss the knowledge

acquisition procedures and the forms of the

questionnaires that were filled by the faculty

members.

The resultant knowledge maps represent the range

of well- and under-developed areas in visual form and

the points of expertise concentration. The concluding

portrait gives a better understanding of the faculty

competencies, equips the academic community with

a better search for collaborators or competitors, and

helps students find research advisors and experts for

consultation. Such knowledge maps help obtain a

practical advantage of knowledge management and

improve practices across organizational cultures and

academic communities.

The logic of the paper is in line with the design

science research and is the following: the current

section 1 provides the motivation for creating a new

approach, section 2 provides a literature review and

highlights the existing research gap, the faculty

knowledge mapping approach and corresponding

method are described in section 3, while section 4

provides a demonstration of this approach and

method.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The concept of knowledge maps seems to be non-

unified and non-formalized due to the lack of

widespread adoption of generally accepted concepts

(Balaid et al., 2016; Hu. 2022). At the same time,

knowledge maps are already deeply integrated into

business life in knowledge-intensive companies with

a long chain of information requests and inquiries

(Eppler, 2004). In this case, knowledge maps are

becoming a crucial tool that allows documenting

every grain of knowledge inside the object of

mapping, in our case, the organization, and helps any

user of the map to find any necessary existing

information.

The classic of visual approach to knowledge

management Martin J. Eppler (2004) proposes the

following classifications of knowledge maps:

1. Knowledge source maps (where the knowledge

is),

2. Knowledge asset maps (what kind of

knowledge we have),

3. Knowledge structure maps (how the knowledge

is organized and interconnected),

4. Knowledge application maps (which

knowledge is needed for performing activities,

producing

required results, and achieving goals),

5. Knowledge development maps (how specific

knowledge is developed).

The first two types are in the focus of the current

paper.

Knowledge Mapping in an Academic Context

(Moradi et al, 2017) applied data-driven methods for

creating knowledge maps for the university. They

created two types of knowledge maps –

Collaboration map and Expertness map – to support

the decision-making of two deans – the Dean of

Research and Dean of Education. They used data

about staff research and educational activities for

creating their maps, but they didn’t reflect the applied

practice activities of employees.

Anthony (2021) suggested a knowledge mapping-

based system for university alumni collaboration, but

this system mostly addresses alumni and does not

provide enough details regarding the method for staff

knowledge/competency assessment and presentation.

The works of (Dorn, 2007; Sánchez, Carracedo,

et al., 2018) suggest student competency maps, which

can be used for curriculum design.

Thus, it can be summarized that knowledge and

competency mapping is actively used in an academic

context, but there is a lack of holistic methods for

mapping faculty competencies, which take into

account not only expertise in research and teaching

but also in applied practice. This combination is of

particular interest and novelty.

3 THE 3D-FACULTY

KNOWLEDGE MAPPING

APPROACH

The presented approach suggests an assessment of the

faculty’s competencies along the three main

dimensions (3D):

Research (R),

Teaching (T) and

Consulting and applied practice (C).

So, the expertise of an employee in each area

should be analysed using these dimensions. Also,

competencies of organizational units and an

organization in general are described using them.

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

186

This approach can be implemented using these

steps:

1. Specify goals and requirements

2. Select experience indicators for each dimension of

faculty’s competencies

3. Define knowledge areas

4. Define data collection method(-s)

5. Collect and verify data

6. Analyse data

7. Create knowledge maps

Goals and requirements (step 1) help making

decisions during the next steps (e.g. what experience

indicator to select, what visualization to choose for

representing knowledge maps).

Table 1: Possible faculty experience indicators (activities).

Dimension Examples of experience indicators

(activities)

(T)

Teaching

Type of involvement (e.g., program

development, course development,

lecturing, practical classes,

assistantship)

Level of educational program (e.g.,

bachelor, master, executive, doctoral)

Level of contribution (from teaching

by the general curriculum to

developing unique programs and

courses)

Type of courses (e.g., large cohort

courses, small cohort courses,

seminars, trainings, workshops)

Level of supervised works at different

levels (e.g., course paper, graduation

p

aper, group project)

(R)

Research

Type of publications (e.g., articles,

textbooks, monographs)

Level of publications (e.g., by journal

quartiles, by journal rankings)

Participation in research grants (e.g.,

level of funding, type of research

project)

Role in the project (e.g., from head of

project to junior researcher)

Type of research

contribution/development (e.g.,

methodology, conceptual framework,

a

pp

lied framework, research method

)

(C)

Consulting

and

applied

practice

Type of involvement (e.g., external

consultant, part-time expert, part-

time employee, full-time employee)

Years of practical experience

Practical publications (e.g., case

studies, handbooks, manuals, expert

interviews, expert articles)

Expertise in consulting (e.g., by

roles, b

y

levels of responsibilities)

Within step 2 each of the three dimensions of

faculty competencies should be further decomposed

into experience indicators based on one or multiple

criteria depending on the needs of the educational

institution (see examples in Table 1).

A choice of experience indicators should be

synchronized with the goals of mapping (e.g., with

the current positioning to identify stronger or weaker

areas or with a prospective vision to determine the

directions for growth).

The three types of experience are then combined

with knowledge areas. These areas can be described

using any knowledge organization system (Step 3):

list of terms, taxonomy, ontology etc. Usually, some

sort of hierarchy will be required to deal with a

multitude of subject areas.

As soon as knowledge areas are specified, the

next step is to organize (step 4) and perform (step 5)

data collection, either using the questionnaire that

will be filled in by the faculty or via the integration of

existing data. The resultant data should combine

faculty knowledge areas with expertise indicators,

which are represented through the performed

activities and achievements.

The collected data should be analyzed (step 6).

Data analysis is based on the assignment of scores for

specific experience indicators (previous activities)

and the aggregation of these scores. Data analysis

provides final data for creating knowledge maps

(visual representations).

Data visualization for presenting faculty

knowledge (step 7) can be done in different

formats (e.g. bar charts, radar charts, treemaps,

sunburst diagrams, e.g.https://datavizcatalogue.com).

Different diagrams should be created for different

target audiences and tasks. The resultant diagrams

can be either static or dynamic (interactive

dashboards). Static representations can be produced

using the diagramming functionality of spreadsheet

software (e.g. MS Excel), while dynamic ones can be

created using BI tools (e.g. MS Power BI, Tableau).

Different data visualization tools can also be used,

e.g. RAWGraphs. So, data visualization techniques

and tools consider data about faculty expertise and

knowledge as another type of data. Thus, these

techniques and tools help to visualize knowledge

maps.

Using Knowledge Maps to Create a Business School Faculty Portrait

187

4 METHOD APPLICATION: THE

CASE OF THE UNIVERSITY

BUSINESS SCHOOL

For the empirical test of the approach, we chose a

relatively small business school owing a place in the

Financial Times European Business School

Rankings.

4.1 Defining the Goals

The need for the knowledge map was driven by the

preparation for the new school strategy development

and the demand for more intense industry-university

collaboration. The following questions were

addressed through the knowledge map:

1. What are the areas with the primary/least

expertise?

2. What knowledge areas are strong or need to be

strengthened from a teaching, research, and/or

consulting (applied practice) perspective?

3. Can the school take or offer consulting, R&D,

or educational projects on the specific topic? Whether

the required competencies exist and are available?

4. Which faculty member can be involved in the

consulting, R&D, or educational project on the

specific topic?

These questions were taken as the starting point

in the process of the data collection.

4.2 Selection of the Experience

Indicators

Then, the experience indicators for each dimension

were selected:

A. For Teaching:

By level of contribution: course renewal, new

course development, new training or business

game development,

By level of educational program:

bachelor/master, doctoral, and executive.

B. For Research:

By types of projects based on grants

categorization: projects with external funding

from research funds, projects with external

funding from industry, projects with internal

funding from the university,

By the role in the project team: Principal

Investigator (PI), Subject Matter Expert (SME),

Executor (doer).

By the types of deliverables created over the

research career (e.g., theoretical models,

analytical reports, research methodology,

management methodology, etc.)

C. For Consulting (Name of Applied Practice in

the Business School):

experience in consulting in different roles

(project architect, project leader, expert,

consultant, communicator),

experience in close-to-consulting teaching

practices (case development, study consulting

projects supervision, R&D experience).

4.3 Knowledge Areas Definition

To define and decompose the subject area, it was

decided to refer to the All Science Journal

Classification (ASJC) System, which is used in

SCOPUS. Categories that are relevant to business

schools were selected, then they were assembled and

merged (in some cases) in order to form a one-level

list of subject areas. It should be noted that in the list,

both thematic areas (e.g., marketing and sales,

entrepreneurship and innovation, finance and

accounting, etc.) and the cross-subject area “methods

of data analysis and decision making” were

identified. The category “interdisciplinary and other

areas” was also added to the list, designed to identify

the unique knowledge of employees.

The next step was to decompose each subject area

to provide the necessary details for expertise

specification. In order to avoid subjectivity and bias

we decided not to create a taxonomy, but rather to

combine high-level areas (classes) with keywords,

inspired mainly by (Kiu C., Tsui E., 2011). To form

and refine the list of keywords, the titles of courses

taught were analyzed, and, if necessary, in-depth

interviews with representatives of expertise areas

were conducted. The suggested sets of keywords

were refined and adjusted, and keywords related to

more than one area of knowledge were also identified.

4.4 Data Collection Method Design,

Questionnaire Creation

Since objective data for many experience indicators

was missing we decided to collect data about faculty

expertise via a questionnaire. The logic of the

questionnaire was the following: each faculty

member first selects the areas in which she considers

herself to possess some expert knowledge (in any of

the three dimensions), and then for each of the chosen

areas marked the keywords that best describe the

individual competences and selected experience

indicators for each of the three dimensions.

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

188

4.5 Data Collection and Verification

When this self-assessment data is collected, it should

be cleaned and verified through either expert cross-

checks (e.g., through related departments) or

secondary sources and databases (to confirm research

and teaching activities).

The survey took place in 2019-2020 academic

year. We received responses from 63 faculty

members, which constitutes about 90% of all business

school faculty. Table 2 represents the resulting data

structure that was repeated for each subject area.

4.6 Data Analysis

In order to assess faculty expertise different values

were assigned to various experience items:

Employee expertise = {AreaExp

ij

}, where

AreaExp

ij

is the expertise of employee i in subject

area j.

AreaExp

ij

= {KW

ij

, Exp

ij

}, where:

KW

ij

– a list of keywords, which represents

employee i fields of expertise in subject area j,

Exp

ij

– experience level of employee i in

subject area j

Expij = TeaExpij + ResExpij + ConExpij, where:

TeaExp

ij

– teaching experience level of

employee i in subject area j

ResExp

ij

– research experience level of

employee i in subject area j

ConExp

ij

– consulting experience level of

employee i in subject area j

In order to assess the business school expertise in

a certain subject area the following formula was

applied:

SA

j

= ∑ Exp

ij

The “dimensional” (T, R, C) expertise of the

business school in a certain subject area j is the

following:

TeaExp

j

= ∑ TeaExp

ij

ResExp

j

= ∑ ResExp

ij

ConExp

j

= ∑ ConExp

ij

Experience level in each dimension is calculated

in a similar manner as a sum of scores for different

activity items, for example:

ResExp

ij

= ∑ ResExpActivityScore

ijx

, where

i – employee, j – subject area,

x – specific research experience activity item

These items were usually a combination of 2 or

more experience aspects, for the assessment of

research experience the first experience aspect was

“Types of research projects” and the second aspect

was “Role in the project”. As a result, example

research experience activity items were:

Principal Investigator (PI) in Research

projects with external funding from

research funds

Executor in Research projects with internal

funding (from the University)

Scores for each experience activity item were

defined by the knowledge mapping team together

with the business school transformation leaders; see

the scores for faculty research experience assessment

in Table 3.

Table 2: Data structure for subject area X.

Employees Keywords Teaching experience Research experience Consulting experience

KW 1

KW 2

KW 3

…

Experience in

course renewal

…

Research projects with

external funding from

research funds

…

Industrial consulting

project

…

Bachelor/ maste

r

Doctoral

Executive

…

Principal

Investigator (PI)

Subject Matter

Expert (SME)

Executor (doer)

…

Project architect

Project manager

Subject Matter

Expert (SME)

Executor (doer)

…

Employee 1 1 1 1 1 1

Employee 2 1 1 1 1 1 1

Employee 3 1 1 1 1 1

…

Using Knowledge Maps to Create a Business School Faculty Portrait

189

Table 3: Scores for faculty research experience assessment.

Research

experience

aspect 2

(Role in

the project)

Research

experience

aspect 1

(Types of

research projects)

Principal Investigator (PI)

Subject Matter Expert

Executor

Research projects with external

funding from research funds

4 3 2

Research projects with external

funding from business or public

authorities

4 3 2

Research projects with internal

funding (from the University)

3 2 1

Research projects without funding 1 1 1

There is a limitation of the approach that the

amount and quality of work within any dimension are

not represented in the evaluation scheme.

4.7 Creation of Knowledge Maps

Survey data analysis resulted in a set of knowledge

maps, which helps to answer questions from section

4.1. Some knowledge maps were “static” and created

using MS Excel, while others were

dynamic/interactive and created using MS Power BI.

Some examples of created knowledge maps are

presented below.

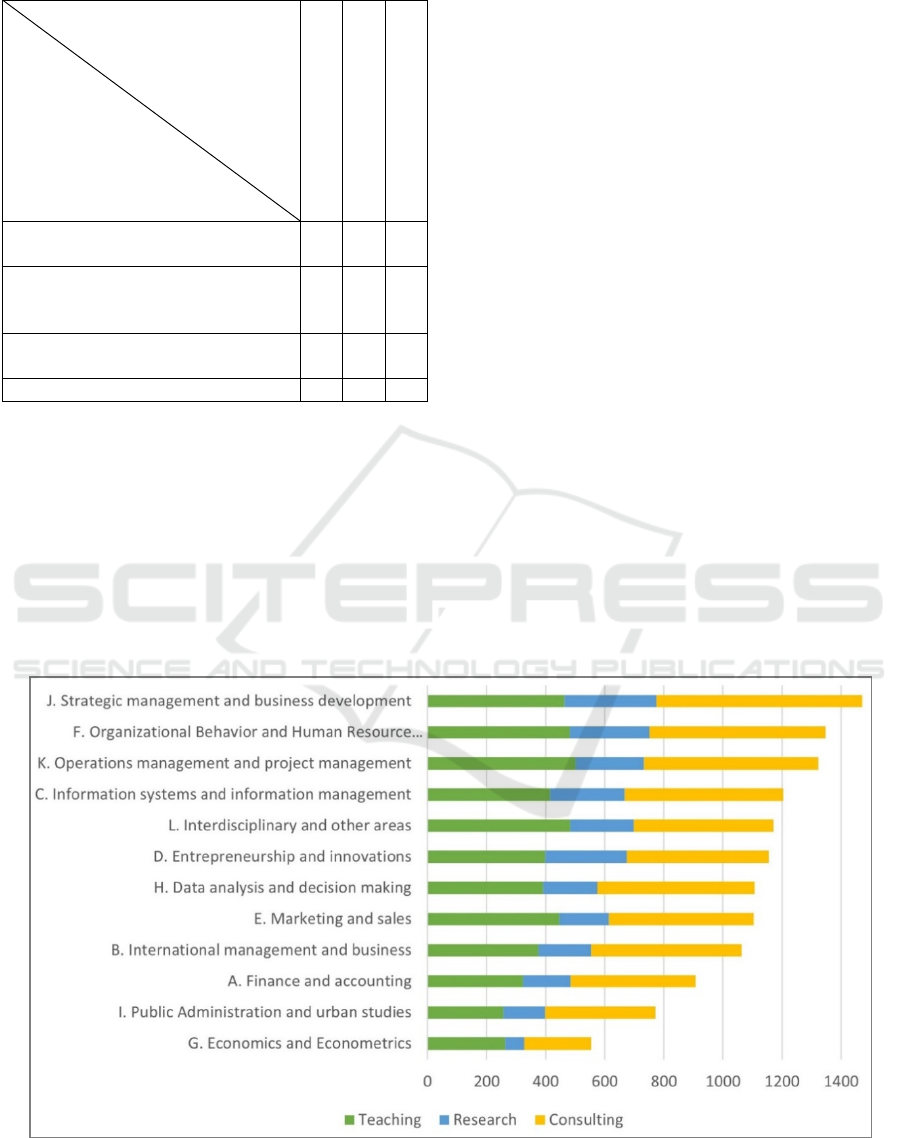

Figure 1 demonstrates 3D knowledge map for the

business school under investigation, it shows the total

level of the business school expertise in different

subject areas. It is based on the following data:

{TeaExp

j

, ResExp

j

, ConExp

j

and SA

j

}. This map

helps to identify the most “powerful” subject areas

and may support business school strategy

development. It is also possible to look at and sort by

the particular dimension for specific purposes, e.g. at

the teaching dimension during teaching-related

decision-making.The map shows that “Strategic

management and business development” is the

strongest knowledge area of the business school,

while “Economics and Econometrics” – is the

weakest. This chart can also be sorted based on the

teaching, research and consulting dimensions. Such

sorting by dimension helps to see that the primary

consulting experience of the school is in “Strategic

management and business development”, while

leading teaching expertise is in “Operations

management and project management”.

We did not analyze it in verbal form, but Figure 1

shows the entire structure and the relative shares of

each activity (teaching/research/consulting) in the

main competency areas. For example, it is seen that

the school lacks consultants and researchers in

econometrics

Figure 1: 3D knowledge map for the selected business school.

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

190

Figure 2: Number of faculty members with expertise in the specific field within “J. Strategic management and business

development” subject area.

Figure 3: Multidimensional faculty profiles for the subject

area “Strategic management and business development”.

Figure 2 demonstrates the details of the business

school’s expertise in the specific subject area – “J.

Strategic management and business development”

was selected as the leader in total expertise level. It

represents the number of employees, which selected

keywords as their area of expertise. The more detailed

specification of knowledge areas (fig. 2) helps answer

question 3 from section 4.1 - Can the school take or

offer consulting, R&D, or educational project on the

specific topic? Whether the required competencies

exist and are available?

Each faculty member may have different

experience levels within each dimension, so 3D

faculty profiles may easily show these differences –

see Figure 3. Such diagrams help to understand the

strengths and weaknesses of each employee.

Figure 3 shows that employees 7 and 41 are

“stars” in “Strategic management and business

development” from all perspectives. While Employee

3 is very important for doing consulting projects,

Employee 2 – is for doing research and Employee 11

– if we think about new teaching initiatives in the

area. This chart helps answering question 4 from

section 4.1 – “Which faculty member can be involved

in the consulting, R&D, or educational project on the

specific topic?”.

Using Knowledge Maps to Create a Business School Faculty Portrait

191

Only a part of knowledge maps was presented in the

paper, while the data collected (see section 4.5)

allowed generating other representations, which

included treemaps, sunburst diagrams, bar charts,

radar charts, and tables. MS Excel and MS Power BI

were used to generate the required views.

5 CONCLUSION & DISCUSSION

In the ever-evolving landscape of higher education, it

is imperative for institutions to have a clear

understanding of their faculty's expertise to foster

more robust industry-university collaborations and

strategic planning. The presented research addresses

this critical need, introducing an innovative approach

for knowledge mapping within a business school

environment. This approach, focusing on the three

main dimensions: Research (R), Teaching (T), and

Consulting and Applied Practice (C), seeks to

holistically capture the multifaceted expertise of

faculty members.

Our empirical examination of this approach was

conducted in a renowned business school, providing

valuable insights into its practical application. The

resultant knowledge maps, which utilized diverse

visual templates from bar to sunburst charts,

illuminated both the strengths and areas of

development within the faculty's expertise. Such

comprehensive visualizations not only bolster the

academic community's capacity to identify potential

collaborators or competitors but also enhance

students' ability to pinpoint suitable research advisors

and consultation experts.

However, like all research, this study is not

without its limitations. The primary method of data

collection, a questionnaire, introduced a degree of

subjectivity into the results. It's inherent in human

nature to sometimes either overestimate or

underestimate one's capabilities, which could have

influenced the final knowledge maps. Moreover, the

current methodology, while effective, requires a

significant manual input, signaling the need for more

automated processes.

In light of these findings and limitations, future

research avenues become apparent. There's a pressing

need to develop automated or at least semi-

automated, data-driven methods for knowledge

mapping. Such advancements would not only

enhance the accuracy of the maps but also make the

process more efficient, catering to larger institutions

with vast faculty numbers.

In summation, this research has contributed a

structured approach for visualizing the intellectual

capital within academic institutions, particularly in a

business school setting. As higher education

institutions continue to evolve, tools and

methodologies such as this will prove instrumental in

facilitating informed decision-making in the realm of

academic expertise and collaboration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work of Tatiana Gavrilova and Olga Alkanova

was partially supported by grant of Russian Science

Foundation (project N 23-21-00168).

REFERENCES

Anthony Jr, B. (2021). Information flow analysis of a

knowledge mapping-based system for university

alumni collaboration: a practical approach. Journal of

the Knowledge Economy, 12(2), 756-787.

Balaid, A., Abd Rozan, M.Z., Hikmi, S.N. and Memon, J.

(2016) Knowledge Maps: A Systematic Literature

Review and Directions for Future Research, International

Journal of Information Management, Vol 36, No. 3, pp

451–475.

Dorn J., Pichlmair M. A (2007) Competence Management

System for Universities // Proc. European Conf. on

Information Systems (ECIS), St. Gallen, Switzerland.

P. 759–770.

Eppler, M. J. (2004) Making Knowledge Visible Through

Knowledge Maps: Concepts, Elements, Cases, in:

Handbook on Knowledge Management (Vol 1), Berlin

Heidelberg: Springer, pp 189–205.

Faisal, H., Rahman, A. and Zaman, G. (2019) Knowledge

Mapping for Research Papers, International Journal of

Computer Science and Network Security, Vol 19, No.

10, pp 158–164.

Hu, Z. (2022). Visual knowledge mapping analysis of

research of digital image processing, In Thirteenth

International Conference on Graphics and Image

Processing (ICGIP 2021) (Vol. 12083, pp. 173-177).

SPIE.

Kiu, C. C., & Tsui, E. (2011). TaxoFolk: A hybrid

taxonomy–folksonomy structure for knowledge

classification and navigation. Expert systems with

applications, 38(5), 6049-6058.

Mazzocchi, F. (2018) Knowledge organization system

(KOS). Knowledge Organization 45, no.1: 54-78. Also

available in ISKO Encyclopedia of Knowledge

Organization, eds. Birger Hjørland and Claudio Gnoli,

accessed 1 September 2023 URL: http://www.

isko.org/cyclo/kos

Moradi, R., Taheri, K., & Mirian, M. S. (2017). Data-driven

methods to create knowledge maps for decision making

in academic contexts. Journal of Information &

Knowledge Management, 16(01), 1750008.

KMIS 2023 - 15th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

192

Sánchez Carracedo, F., Soler, A., Martín, C., López, D.,

Ageno, A., Cabré, J., Garcia, J., Aranda, J. and Gibert,

K. (2018) Competency Maps: An Effective Model to

Integrate Professional Competencies Across a STEM

Curriculum, Journal of Science Education and

Technology, Vol 27, No. 5, pp 448–468.

Using Knowledge Maps to Create a Business School Faculty Portrait

193