There Are no Major Age Effects for UX Aspects of Voice User Interfaces

Using the Kano Categorization

Jana Deutschl

¨

ander

1 a

, Anna C. Weigand

1,2 b

, Andreas M. Klein

1,2 c

, Dominique Winter

3 d

and Maria Rauschenberger

1 e

1

Faculty of Technology, University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer, Emden, Germany

2

Department of Computer Languages and Systems, University of Seville, Seville, Spain

3

University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany

Keywords:

Voice User Interfaces, User Experience, UX Aspects, Kano, Categorization, Voice Assistants, Mixed Methods.

Abstract:

Voice user interface (VUI) evaluation often focuses on user experience (UX) quality measurement of UX

aspects for VUIs. However, it is crucial to differ among these UX aspects concerning their relevance to

specific target groups, like different usage contexts, or user characteristics such as age. Therefore, we identified

potential age-specific characteristics and determine their nature, if any. We applied the Kano model using an

age-segmentation to categorize these 32 UX aspects based on VUI user data (N = 384). Our findings reveal

that UX aspects of VUIs are broadly consistent across all age groups, and VUI developers and researchers

should consider the important ones. Some age effects are visible and could impact the success of VUIs.

1 INTRODUCTION

When developing or enhancing voice user interfaces

(VUIs), the need of younger users should no longer

be the primary consideration as the middle-aged and

older adults using technological devices increase as

well (Czaja et al., 2006; Jenkins et al., 2016; Lee and

Coughlin, 2014). Hence, it is important to provide a

good user experience (UX) for users of all ages. Fo-

cusing on relevant UX aspects enables efficient prod-

uct development and evaluation. K

¨

olln et al. iden-

tified a list of potential UX aspects for VUIs (K

¨

olln

et al., 2022a), and then prioritized them using the

Kano method (K

¨

olln et al., 2023a). This prioritization

was conducted in a segment-unspecific manner. How-

ever, it is necessary to identify relevant differences be-

tween these UX aspects in terms of their importance

for specific target groups, e.g., different usage con-

texts or user characteristics such as age (Klein et al.,

2023a; Strassmann et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2022).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3851-4384

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2674-0640

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3161-1202

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2697-7437

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5722-576X

To the best of our knowledge, the effects of age

on these UX aspects of VUIs have not yet been re-

searched in detail. Thus, we investigated whether

age-specific particularities can be identified and, if

so, which ones. We collected a data set (N = 384)

to apply an age-segmented Kano categorization and

evaluate it, with the goal of answering the following

research questions (RQ):

• RQ1: Are there any differences in categorizing

UX aspects based on user age?

• RQ2: Are there any UX aspects that are more im-

portant for a specific age group?

2 BACKGROUND & RELATED

WORK

Considering specific UX aspects for VUIs is an indis-

pensable evaluation method to effectively meet users’

needs. Therefore, we first describe the existing VUI

UX aspects and known age effects before we go into

detail about the Kano categorization of VUI UX as-

pects as well as the Kano model (KM) itself.

330

Deutschländer, J., Weigand, A., Klein, A., Winter, D. and Rauschenberger, M.

There Are no Major Age Effects for UX Aspects of Voice User Interfaces Using the Kano Categorization.

DOI: 10.5220/0012187600003584

In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2023), pages 330-339

ISBN: 978-989-758-672-9; ISSN: 2184-3252

Copyright © 2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

2.1 UX Aspects & Age-Related Effects

UX aspects for VUIs have already been researched

and 32 of them have been identified as relevant (K

¨

olln

et al., 2022a; K

¨

olln et al., 2022b; K

¨

olln et al., 2023a;

K

¨

olln et al., 2023b). VUI developers can use these

UX aspects as a starting point to determine their de-

velopment focus or to improve the quality of existing

VUIs (Klein et al., 2023b), e.g., by developing VUI

measurement tools (Klein et al., 2020c; Klein et al.,

2020b). The categorization and prioritization under-

lying this assessment can be done using various meth-

ods, including the Kano method (K

¨

olln et al., 2023a).

Since the UX aspects of VUIs are relatively new,

there are no studies yet on how age influences them.

However, there have been indications that age influ-

ences how VUIs are used. Children, for instance,

interact playfully and ask for audio games, while

their parents request weather reports (Klein et al.,

2023a). Seniors evaluate virtual assistants more posi-

tively than do young adult students (Strassmann et al.,

2020). Younger, middle-aged, and older adults have

been shown to vary in their VUI requirements, which

impacts acceptance (Zhong et al., 2022).

2.2 The Kano Model (KM)

The KM (Kano et al., 1984) is a concept for classify-

ing and prioritizing customer requirements for a prod-

uct. UX aspects describe the UX quality of the user’s

interaction with the product. Therefore, we can cate-

gorize UX aspects according to the KM, which clas-

sifies product characteristics into three quality cate-

gories with varying impacts on customer satisfaction

(Witell et al., 2013). These categories are: Must-be

quality: Expected, causes dissatisfaction when ab-

sent. One-dimensional quality: Satisfies customers

when present and dissatisfies when not present. At-

tractive quality: Provides satisfaction when present,

but absence is acceptable.

In addition, there are two more quality categories

(Kano et al., 1984): indifferent and reverse. For the

indifferent quality, satisfaction is not affected by the

presence of a characteristic. For the reverse qual-

ity, the presence of a characteristic is perceived neg-

atively. The categorization of the individual qual-

ity characteristics into the KM is done by answering

two five-point rating scale questions: (1) the func-

tional question captures a customer’s reaction when

the given product characteristic is present, and (2) the

dysfunctional question captures a customer’s response

when the characteristic is not present.

Using Discrete Analysis for KM. First, based on

the combination of the responses to the functional

and dysfunctional questions, the corresponding cat-

egories are determined for each study participant us-

ing the Kano evaluation. Illogical answers are placed

in a special category questionable and must be dis-

carded. Then, all categorizations are summed up,

and the most frequently mentioned category is used

as the overall Kano category. A relative majority, no

matter how small, is sufficient (Kano et al., 1984).

The overall percentage of respondents for whom the

product feature is highly important is reflected by

the Total Strength, which is calculated as follows

using percentages: Total Strength = Attractive +

One-dimensional + Must-be.

Applying discrete analysis for Kano categoriza-

tion results in information loss due to strict assign-

ment based on relative majorities, despite the data dis-

playing a spectrum-like nature. Another way to cate-

gorize product features according to the KM is by us-

ing continuous analysis (DuMouchel, 1993; Timko,

1993).

Using Continuous Analysis for KM. The continu-

ous analysis method overcomes the most significant

limitation of the discrete analysis method by using

satisfaction and dissatisfaction coefficients to include

all collected information in the categorization (Berger

et al., 1993). The discrete analysis approach does not

assign specific values to features, whereas the con-

tinuous analysis approach uses a scale to evaluate

the Kano survey. To do so, each feature is assigned

a numerical value according to the answers to the

functional and dysfunctional questions (DuMouchel,

1993). The mean value is calculated for the overall

category. This graphical representation (positive val-

ues from 0 to 4) of individual features and their as-

signment to categories can illustrate trends, even if

they are subtle (Berger et al., 1993).

3 USER STUDY

This section describes its participants, our approach,

and our final data set. We choose the Kano model, a

proven method widely used in both practice and re-

search.

3.1 Age Segmentation

Since we investigate age-related effects of VUI UX

aspects, we use an appropriate age segmentation

method derived from the literature. Specifically, we

define three age groups with the following ranges:

• Younger Adults: 18 to 34 years

• Middle-aged Adults: 35 to 44 years

• Older Adults: 45 to 85 years

There Are no Major Age Effects for UX Aspects of Voice User Interfaces Using the Kano Categorization

331

This is based on the idea that ages are commonly

grouped into a small number of crude age ranges

that either reflect the major stages of human devel-

opment and aging or form meaningful, contextual age

groups (Erikson, 1994; Sigelman and Rider, 2008).

Our chosen segmentation has already been estab-

lished in market analyses of VUI use (Lis, 2022; Tas¸

et al., 2019).

3.2 Procedure

We build upon an exisiting quantitative online user

study (N = 219) (K

¨

olln et al., 2023a). Our method-

ology, including categorization choices, follows their

prior work.

Data Collection. The previous online user study was

conducted between January 31 and February 3, 2023

(K

¨

olln et al., 2023a). We extend that study with our

data, which was collected from April 12-13, 2023.

Given the short time span between the two studies,

no significant new VUI developments emerged dur-

ing this period.

Questionnaire. Our study participants are given the

same online questionnaire as already used in the prior

study (K

¨

olln et al., 2023a) in which they are asked

for their demographic data, general questions about

themselves, their VUI use, followed by the Kano

questions.

Recruitment. In the previous study, participants

were recruited from the USA (n = 106) and UK

(n = 110). To minimize cultural effects in our study,

we recruited additional participants from two other

English-speaking countries, Canada (n = 101) and

Australia (n = 102). All participants were recruited

via the crowd-working platform Prolific (Prolific Aca-

demic Ltd., 2023), which provides a subject pool for

research (Palan and Schitter, 2018) with high-quality

data (Peer et al., 2021) appropriate for our user study.

Subject Exclusion. For data cleaning of the total 419

records, we used the exclusion criteria already applied

in the previous study (K

¨

olln et al., 2023a). These are,

more than three questionable features (n = 13), more

than 28 identical categorizations (n = 19), or less than

two seconds per item (n = 14). age under 18 or over

85 (n = 2), with corrupted data in this field (n = 3),

when asked about the VUI used, the respondent indi-

cated “none” (n = 1). Participants were excluded if

one or more of these criteria were met.

3.3 Final Data Set

Our final data set includes N = 384 participants, sep-

arated into participants from the USA (n = 95), UK

(n = 97), Canada (n = 89), Australia (n = 94), and

other countries (n = 9). It has the following age dis-

tribution: Younger Adults (n = 187), Middle-aged

Adults (n = 112), Older Adults (n = 85).

The gender distribution is as follows: male (n =

168), female (n = 207), diverse (n = 6), and prefer not

to say (n = 3). All our study participants use at least

one VUI device, with the following device distribu-

tion: Alexa (n = 182), Siri (n = 203), Google Assis-

tant (n = 175), and others, such as Bixby, car monitor,

or Dragon Naturally Speaking (n = 62). The reasons

for VUI usage also vary: participants use them for

fun (n = 240), for comfort (n = 222), for professional

reasons as a tool at work (n = 59), for professional

reasons in scientific research (n = 10), due to motor

impairment (n = 7), and other (n = 77).

3.4 Age-Related Kano Categorization

UX aspects can be assigned to the expectations of

users according to the aforementioned categoriza-

tion (Kano et al., 1984) for each age group.

To categorize the UX aspects relevant to VUI

users of each age group into specific Kano categories,

we first apply the discrete analysis (Kano et al.,

1984). We then employ Fong Test to determine the

Self-Stated Importance and whether the categoriza-

tion is significant (Fong, 1996). Furthermore, we

consider both the Total Strength and the distributions

of percentages for each UX aspect within each age

group (Lee and Newcomb, 1997).

The discrete analysis method does not include all

information; hence, we also use the continuous anal-

ysis method to consider all our data sets’ information.

We first evaluate the graphs of our continuous analy-

sis results to discover any differences in the Kano cat-

egorizations of the age groups. Therefore, horizon-

tal (dysfunctional dimension) or vertical (functional

dimension) rating differences between age groups in

combination with shifts from one Kano category to

another are relevant for our study. These shifts may

be marginal or substantial across age groups.

4 RESULTS

In the following, we present the results of our quanti-

tative user study (N = 384).

4.1 Discrete Analysis

The percentage distribution of ratings by study partic-

ipants for the discrete analysis is shown in Table 1.

Moreover, we examine whether the categorization

is significant, which is depicted in Table 2.

WEBIST 2023 - 19th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

332

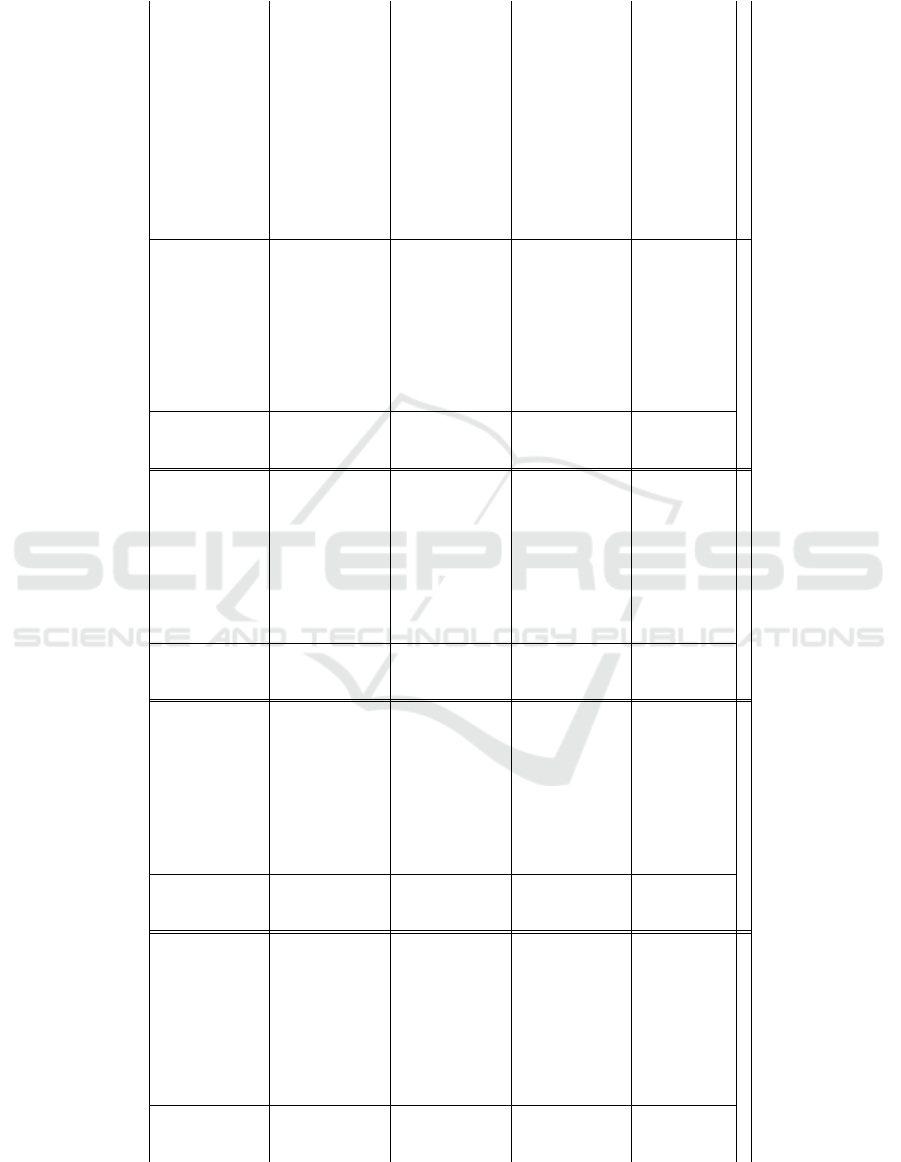

Table 1: Percentage distributions of all 32 UX aspects and Kano categories, results of the Fong Test, and Total Strength for all

study participants, as well as younger, middle-aged, and older.

All (N = 384) Younger (n = 187) Middle-Aged (n = 112) Older (n = 85)

UX Aspect

Must-be

One-Dimensional

Attractive

Indifferent

Reverse

Questionable

Test of Fong

Total Strength

Must-be

One-Dimensional

Attractive

Indifferent

Reverse

Questionable

Test of Fong

Total Strength

Must-be

One-Dimensional

Attractive

Indifferent

Reverse

Questionable

Test of Fong

Total Strength

Must-be

One-Dimensional

Attractive

Indifferent

Reverse

Questionable

Test of Fong

Total Strength

Ad-Free 51 32 9 6 0 1 * 92 50 33 10 6 0 1 * 90 55 31 6 7 0 0 * 92 48 31 13 5 0 4 * 92

Aesthetic 18 12 18 39 7 6 * 48 17 12 20 36 8 7 * 49 21 11 16 43 6 3 * 48 18 15 16 38 5 8 * 49

Capability to Learn 22 30 21 20 5 1 * 73 20 27 23 22 6 2 * 70 44 41 6 8 0 1 * 91 31 35 13 16 4 1 * 79

Comprehension 20 48 20 10 1 0 * 88 20 41 26 12 1 0 * 87 21 54 15 9 1 1 * 90 21 58 11 9 1 0 * 90

Context Sensitivity 18 28 17 23 11 3 * 63 20 29 13 25 9 4 62 13 25 21 23 14 3 59 21 32 20 16 11 0 73

Convenience 22 40 20 17 1 0 * 82 21 40 24 14 1 1 * 85 26 43 13 18 0 0 * 82 19 36 20 21 4 0 * 75

Customizability 8 18 39 32 2 1 * 65 7 16 44 29 3 1 * 67 7 15 38 38 1 1 50 12 26 27 32 2 1 65

Data Security 66 30 1 1 1 1 * 97 63 32 3 2 1 1 * 98 75 21 0 1 2 1 * 96 60 36 0 1 0 2 * 96

Effectivity 21 36 22 20 1 0 * 79 19 33 25 22 1 1 * 77 23 42 19 16 0 0 * 84 24 35 19 21 1 0 * 78

Efficiency 21 34 28 15 1 2 * 83 19 31 30 16 1 2 80 25 32 29 13 0 1 86 20 41 19 18 0 2 * 80

Error-Free 36 45 13 5 0 2 * 94 33 42 16 6 0 3 * 91 40 43 11 4 0 2 94 35 52 8 4 0 1 * 95

Flexibility 18 34 25 22 2 0 * 77 18 33 27 22 1 0 78 17 33 26 21 4 0 76 22 36 18 22 1 0 * 76

Fun 15 34 27 21 2 1 * 76 14 31 29 22 2 1 74 16 36 25 20 4 0 * 77 15 38 26 19 1 1 79

Help with Errors 32 40 18 10 0 1 * 90 32 39 19 9 0 1 90 33 40 17 9 0 1 90 28 44 15 13 0 0 * 87

Humanity 7 8 26 45 13 1 * 41 6 7 22 50 13 1 * 35 6 8 30 41 13 2 * 44 7 12 27 40 14 0 * 46

Independence 27 31 24 17 1 0 82 27 31 25 16 1 0 83 26 31 24 19 0 0 81 26 32 21 16 4 1 79

Innovation 13 29 31 27 1 0 73 13 32 34 20 1 0 79 8 26 32 34 0 0 66 16 26 22 34 1 0 64

Intuitiveness 43 38 9 10 0 0 90 38 36 12 13 1 0 86 44 41 6 8 0 1 91 52 36 8 4 0 0 * 86

Link 3rd-Party Products 18 27 20 24 7 3 65 19 26 19 26 7 2 64 16 26 21 24 9 4 63 19 31 20 21 5 5 70

Longevity 46 44 5 5 0 0 95 43 44 7 6 0 0 94 50 43 3 4 1 0 96 47 47 1 5 0 0 95

Personal Fulfillment 28 38 16 16 1 1 * 82 28 36 18 17 1 0 * 82 32 38 15 13 0 2 85 25 44 13 18 1 0 82

Politeness 44 40 8 7 1 0 92 40 42 10 7 1 0 92 45 39 6 8 1 1 90 51 38 5 6 1 0 * 94

Practicality 14 41 25 19 1 0 * 80 13 41 29 16 1 0 * 83 15 39 23 21 1 0 * 77 13 45 19 21 2 0 * 77

Privacy 50 32 2 2 3 11 * 84 52 33 2 1 3 10 * 87 53 29 2 1 3 13 * 84 42 35 1 5 2 14 78

Range of Functions 14 26 26 30 4 1 66 14 24 30 29 3 0 68 15 26 24 30 3 2 65 9 29 20 33 7 1 58

Reliability 48 43 4 4 0 1 95 49 41 6 4 0 0 96 52 42 1 2 0 4 95 42 49 2 6 0 0 93

Responsiveness 42 36 11 10 0 1 89 40 36 11 12 0 1 87 45 34 13 7 1 1 92 42 39 8 11 0 0 89

Safety 39 36 7 14 3 2 82 36 33 7 19 3 2 76 43 35 8 10 2 3 86 39 42 5 9 5 0 86

Simplicity 35 53 6 6 0 0 * 94 28 53 9 9 1 0 * 90 42 51 4 4 0 0 97 40 54 1 4 0 1 * 95

Support of the User 19 44 21 14 1 1 * 84 18 43 22 16 1 1 * 83 21 45 21 13 1 0 * 87 21 46 19 12 1 1 * 86

Time-Saving 20 42 18 18 2 1 * 80 19 44 17 17 2 1 * 80 19 42 22 15 2 0 * 83 26 36 13 22 2 0 75

Voice 38 46 9 7 0 0 * 93 34 48 11 7 0 0 * 93 44 41 6 9 0 0 91 40 48 7 5 0 0 95

(bold = rated by the relative majority, * = significant)

There Are no Major Age Effects for UX Aspects of Voice User Interfaces Using the Kano Categorization

333

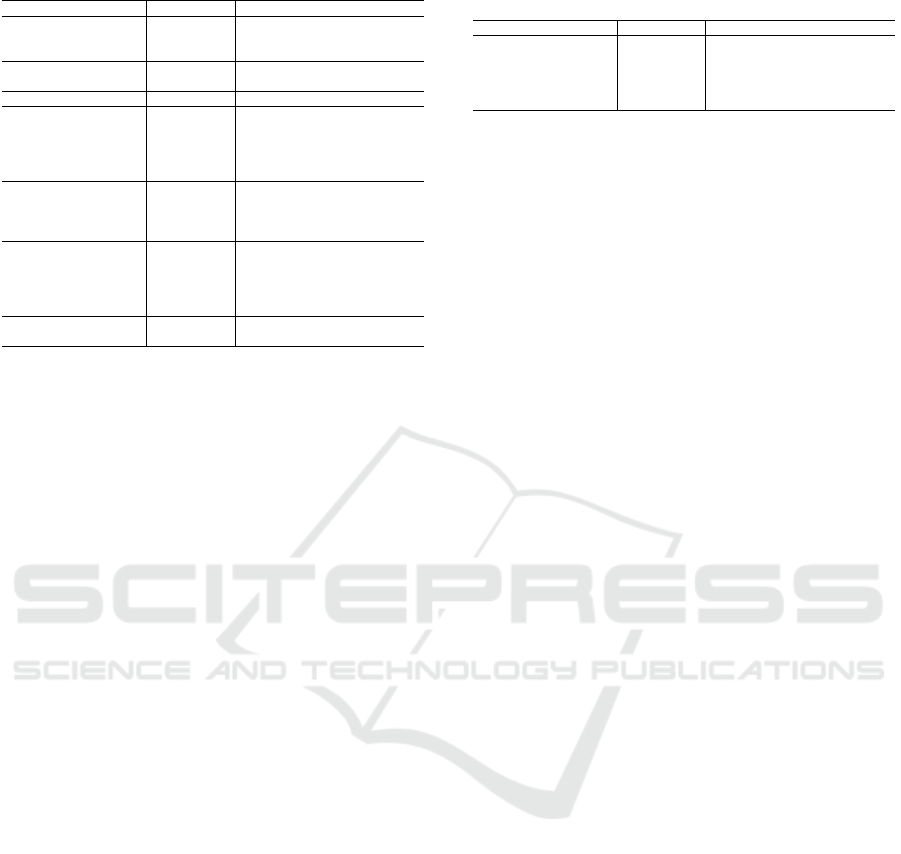

Table 2: Significant results of the discrete analysis.

UX Aspect All (N = 384) Younger Middle-Aged Older

Ad-Free M M M M

Data Security M M M M

Privacy M M M -

Aesthetic I I I I

Humanity I I I I

Customizability A A - -

Comprehension O O O O

Convenience O O O O

Effectivity O O O O

Practicality O O O O

Support of the User O O O O

Error-Free O O - O

Personal Fulfillment O O - O

Simplicity O O - O

Time-Saving O O O -

Fun O - O -

Efficiency O - - O

Flexibility O - - O

Help with Errors O - - O

Voice O O - -

Capability to Learn O - - -

Context Sensitivity O - - -

(O = One-Dimensional, M = Must-Be, A = Attractive, I = Indifferent)

This table reveals that the significant category as-

signed to each UX aspect is consistent across age

groups. Deviations between the age groups are lim-

ited to whether and how often a category can be sig-

nificantly assigned at all. None of these categories are

assigned when the percentage distribution (see Table

1) is not significant. In such cases, the highest value

is assigned to the same Kano category, but the differ-

ence from the value of the second highest category

is too small to meet the threshold for significance ac-

cording to the Fong Test (Fong, 1996).

Significant Categorizations. Based on the ratings of

All study participants, 16 out of 32 UX aspects are

significantly categorized as one-dimensional (see Ta-

ble 2). For the first five UX aspects this is consistently

true for both the overall group of study participants

and each individual age group.

Three UX aspects are significantly categorized

as must-be by All study participants (see Table 2).

Ad-Free and Data Security are also significantly cate-

gorized as must-be by each age group. Privacy, how-

ever, is significantly categorized by all groups except

the older study participants. Customizability is the

only UX aspect significantly categorized as attractive.

Two UX aspects, are significantly categorized as

indifferent by All study participants as well as every

age group.While the assignment of the Kano category

indifferent is homogeneously significant for the three

age groups, that is not always the case for the cate-

gories must-be, one-dimensional and attractive.

The UX aspects Capability to Learn and Con-

text Sensitivity were significantly categorized as one-

dimensional by All study participants, but no clear

age-specific categorization is identifiable.

Categorizations without Significance. Ten UX

aspects are not significantly categorized into any

Table 3: Non-significant results that meet the threshold of

importance for at least one age group stated in percent.

UX Aspect All (N = 384) Younger Middle-Aged Older

Longevity 95 94 96 95

Reliability 95 96 95 93

Politeness 92 92 90 94

Intuitiveness 90 86 91 86

Responsiveness 89 87 92 89

(bold = important)

Kano category based on the ratings of All study

participants. Two of these have a significant catego-

rization for at least one age group, but eight, a distinct

majority, have no significant categorization for any

age segment. However, this does not necessarily

imply that these UX aspects are less important.

To account for this fact, another weighting mea-

sure is added to the discrete analysis: Total Strength.

This measure can be used to support trade-off de-

cisions in product development (Lee and Newcomb,

1997). We see it as a valid means of prioritizing UX

aspects that are not significantly categorizable.

Lee and Newcomb (1997) propose a threshold

of 60%. The majority of UX aspects in our study

have a Total Strength significantly higher than 60%.

Therefore we derive the importance of a UX aspect

from the consensus of the vast majority of users,

which we assume from a threshold of 90%. We refer

to this hereafter as the threshold of importance.

Five additional UX aspects meet the threshold of

importance for at least one age group, see Table 3.

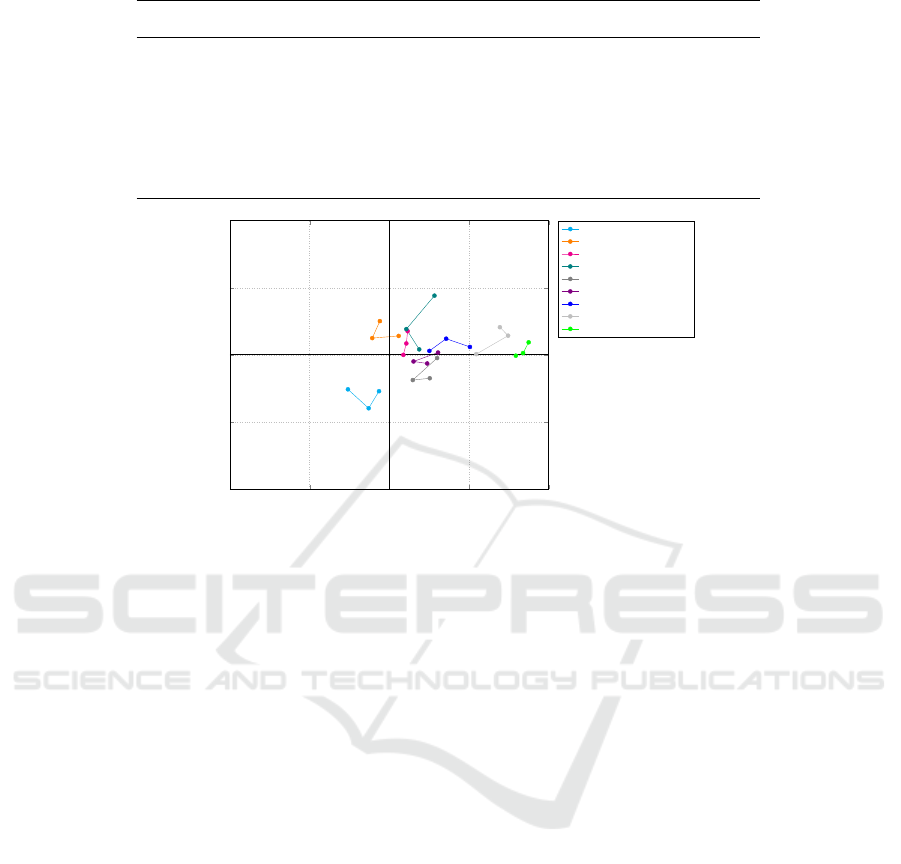

4.2 Continuous Analysis

In the following, we present the results of the continu-

ous analysis (DuMouchel, 1993). We only present the

shifts over time of the UX aspects from which we ex-

pect to gain further insights via the continuous analy-

sis (see Table 4 and Figure 1). It depicts, e.g., horizon-

tal differences (i.e., for the dysfunctional dimension)

between the three age groups.

For the UX aspect Capability to Learn Table 4

shows a difference of 0.509 within the dysfunctional

dimension from younger (Dys f unctional[DF] =

2.503) over middle-aged (DF = 2.714) to older

(DF = 3.012). Overall, younger and older study

participants tend toward the must-be category and not

into the one-dimensional category. Figure 1 shows a

difference between the three age groups in the func-

tional dimension of the UX aspect Innovation. There

is a descending difference of 0.800 from younger

(Functional[F] = 2.882) to middle-aged (F = 2.384)

to older study participants (F = 2.082) (see Table

4). Therefore, the younger study participants clearly

define Innovation as one-dimensional, while the

older participants tend more toward must-be.

WEBIST 2023 - 19th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

334

Table 4: Relevant results of the continuous analysis (N = 384).

UX Aspect Functional Dysfunctional

Younger Middle-Aged Older Younger Middle-Aged Older

Aesthetic 1.487 1.205 1.459 1.481 1.741 1.871

Capability to Learn 2.059 2.241 2.118 2.503 2.714 3.012

Context Sensitivity 1.652 1.625 1.953 2.508 2.295 2.600

Customizability 2.503 2.250 2.282 1.882 1.786 2.118

Innovation 2.882 2.384 2.082 2.567 2.214 2.376

Link 3rd-Party Products 1.872 1.902 2.035 2.476 2.304 2.612

Privacy 2.187 2.027 1.988 3.749 3.679 3.588

Range of Functions 2.353 2.170 2.000 2.230 2.214 2.176

Safety 2.011 2.286 2.412 3.091 3.491 3.388

0 1 2 3 4

0

1

2

3

4

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

Attractive

Indifferent

One-dimensional

Must-be

Dysfunctional

Functional

A: Aesthetic

B: Customizability

C: Range of Functions

D: Innovation

E: Context Sensitivity

F: Link 3rd-party products

G: Capability to learn

H: Safety

I: Privacy

Figure 1: Relevant results of the continuous analysis (N = 384).

Regarding Range of Functions, a decreasing dif-

ference of 0.353 from younger (F = 2.353) to middle-

aged (F = 2.170) to older (F = 2.000) is represented

in Figure 1. Categorizing this UX aspect into the

Kano model changes by increasing age from one-

dimensional toward must-be.

For Privacy, the difference is 0.199 in the func-

tional dimension, from younger (DF = 2.187) to

middle-aged (DF = 2.027) to older (DF = 1.988).

Additionally, there is a difference of 0.160 over

time in the dysfunctional dimension, from younger

(DF = 3.749) to middle-aged (DF = 3.679) to older

(DF = 3.588). This means there is an observable

shift from the must-be to the one-dimensional quad-

rant. Older participants categorize more toward must-

be, while the younger group tend more toward one-

dimensional. Middle-aged (F = 2.286, DF = 3.491)

and older (F = 2.412, DF = 3.388) participants

clearly categorize Safety as one-dimensional. How-

ever, the younger group (F = 2.011, DF = 3.091)

tend more toward the must-be quadrant. Customiz-

ability is categorized as attractive by younger (F =

2.503, DF = 1.882) and middle-aged participants

(F = 2.250, DF = 1.786), whereas the older group

(F = 2.282, DF = 2.118) categorized it as one-

dimensional.

Regarding Link 3rd-Party Products the older

participants (F = 2.035, DF = 2.612) decided

marginally for the Kano category one-dimensional,

while younger (F = 1.872, DF = 2.476) and middle-

aged (F = 1.902, DF = 2.304) study participants

categorized it more as must-be. Figure 1 also depicts,

for the UX aspect Context Sensitivity, a tendency of

older study participants (F = 1.953, DF = 2.600)

toward the Kano category one-dimensional, whereas

younger (F = 1.652, DF = 2.508) and middle-aged

study participants (F = 1.625, DF = 2.295) catego-

rize it as must-be. The UX aspect Aesthetic is clearly

defined as indifferent. Nevertheless, Figure 1 shows

a tendency from younger (F = 1.487, DF = 1.481)

to middle-aged (F = 1.205, DF = 1.741) to older

(F = 1.459, DF = 1.871) toward the must-be Kano

quadrant.

5 DISCUSSION

We aim to understand the differences or similarities

between our selected age groups (younger, middle-

aged, and older adults) in terms of categorizing UX

aspects according to the KM (RQ1). Furthermore, we

discover whether there are UX aspects that are more

important for specific age groups (RQ2).

Age-segmented categorization is necessary to

better understand the target group and helps VUI

developers to determine how much they need to

adjust UX aspects for different age groups (Song

et al., 2022; Zhong et al., 2022). There are notable

There Are no Major Age Effects for UX Aspects of Voice User Interfaces Using the Kano Categorization

335

contrasts in use, evaluation, and acceptance across

ages (Klein et al., 2023a; Strassmann et al., 2020;

Zhong et al., 2022).

However, we did not find any major age effects

for UX aspects of VUIs. In other words, VUI UX as-

pects are consistent over age segments and should be

addressed by VUI developers and researchers. Still,

some age effects are visible and could affect the suc-

cess of a VUI. We elaborate on our findings below.

5.1 Significant Categories

Must-be Category. Two UX aspects, Ad-Free, and

Data Security, are significantly categorized as must-

be by the study participants of all three age groups.

Must-be UX aspects, as per Kano’s categorization

(Kano et al., 1984), are essential considerations for

VUI developers since neglecting them leads to user

dissatisfaction.

Data Security has by far the highest Total Strength

across all age groups, ranging between 96% and 98%.

This UX aspect is essential for VUI users of all ages

due to the significant categorization as must-be and

the very high Total Strength values. These findings

are consistent with existing studies that revealed VUI

use concerns regarding data security and privacy

(Tas¸ et al., 2019; Rauschenberger, 2021; Ammari

et al., 2019), and identified specific VUI user groups,

such as tech-savvy users (BVDW, 2017; Klein et al.,

2020a). While data security is a priority for all users

regardless of their age, individuals with accessibility

needs tend to accept a loss of data security when it

means more convenience (Vimalkumar et al., 2021).

In the discrete analysis, Privacy is significantly

categorized as must-be by all study participants ex-

cept the Older adults. Usually, older VUI users tend

to weigh privacy concerns against preserving their au-

tonomy in daily life (Townsend et al., 2011). Notice-

able, however, are the comparatively high values of

13% and 14% for the Kano categorization question-

able for the middle-aged and older age groups. The

predominant majority of the UX aspects were catego-

rized as questionable in only the 0 - 3% range, occa-

sionally higher, but always in the single-digit range. It

cannot be ruled out that the description of this aspect

in the survey was not formulated clearly enough for

the two age groups or that a subgroup is not aware of

the exact expression.

In the Continuous Analysis diagram (see Figure 1)

the UX aspect Privacy shows a shift from the must-

be to the one-dimensional quadrant. This shift indi-

cates that older participants categorize Privacy more

toward must-be, while the younger adults tend more

toward the one-dimensional category. This UX aspect

tends to be assumed by older users and must be taken

into account, but a particularly good implementation

does not increase their satisfaction. The younger age

group, however, explicitly demands the fulfillment of

this aspect, so the degree of consideration of the UX

aspect can trigger both satisfaction and dissatisfac-

tion. This lends more credence to the previously ex-

pressed assumption that study participants seek a bal-

ance between privacy and autonomy (Townsend et al.,

2011).

One-Dimensional Category. UX aspects signifi-

cantly categorized as one-dimensional should always

be considered by the VUI developer. This category

induces user satisfaction when fulfilled and dissatis-

faction when unfulfilled (Kano et al., 1984).

We identify five UX aspects significantly catego-

rized as one-dimensional across all age groups. No

matter the age of the VUI user group, these UX as-

pects should always be considered.

Efficiency, Flexibility, and Help with Errors are

significantly one-dimensional only for the older age

group. Younger and more tech-savvy (BVDW, 2017)

and middle-aged (Tas¸ et al., 2019) VUI users show a

high frequency of use. This could be why Help with

Errors induces slightly more user satisfaction when

fulfilled for older users. It may also be partly due to

the lack of technology education and experience in

their youth, which could make proper error handling

or coaching more essential (Lee and Coughlin,

2014). The Total Strength values among the younger

and middle-aged participants meet our threshold of

importance and are slightly higher than that of older

ones. Thus, Help with Errors is an essential UX

aspect for these age groups even without significant

categorization.

Error-Free and Simplicity are significantly catego-

rized as one-dimensional by the younger and older

age groups. Older adults tend to dislike technology

that requires too much effort to learn how to use it

(Mitzner et al., 2010). A user study found that per-

ceived ease of use significantly impacted the adop-

tion and attitudes of older individuals with limited

technology experience toward VUIs (Pradhan et al.,

2020). Younger adults often use VUIs for entertain-

ment and communication (Zhong et al., 2022). Media

selection and voice transmission are typical use cases,

and privacy issues and speech intelligibility are the

main requirements (Klein et al., 2021). Speech intel-

ligibility is necessary for correct command execution,

which fits our results for Error-Free and Simplicity.

Attractive Category. Significantly attractive UX as-

pects excite the user instead of just satisfying their ba-

sic needs (K

¨

olln et al., 2023a). If these aspects are not

present, VUI users might not miss them. However,

WEBIST 2023 - 19th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

336

they can increase satisfaction when included (Lee and

Newcomb, 1997; Chen and Chuang, 2008). We iden-

tify only one UX aspect Customizability that is signif-

icantly categorized as attractive for the younger age

group. While it might not be essential to set the per-

sona of a VUI according to the user’s preferences, it

may increase satisfaction when included. Such a fea-

ture can be considered advanced and rather interest-

ing for users with a higher frequency of use. Younger

users tend to be more tech-savvy (BVDW, 2017) and

show a higher frequency of use than older ones, which

could be a reason for this trend.

Indifferent Category. In the KM, indifferent require-

ments have no impact on customer satisfaction, re-

gardless of the degree of fulfillment.

According to the results of the discrete analysis,

no special consideration needs to be given to the UX

aspects Humanity and Aesthetic. This is also sug-

gested by their Total Strength values, which are both

significantly below 50% for each age group. Con-

sidering the 32 UX aspects in the study, the Total

Strength value of Humanity for younger adults is the

lowest value of all at 35%. In the continuous analysis,

these UX aspects are also categorized as indifferent.

Nonetheless, the importance of Aesthetic in-

creases slightly with age and tends in the direction

of the must-be quadrant. Various studies have al-

ready examined the influence of product aesthetics on

perceived usability and UX, exploring notions such

as the “what is beautiful is good” effect (Chaouali

et al., 2019; Haimes, 2021; Tractinsky et al., 2000).

However, the vast majority of these studies exam-

ine visual aesthetics rather than aesthetics perceived

through one of the other sensory channels, such as

audition (Sauer and Sonderegger, 2022). Since both

visual and non-visual aesthetics could play a role in

the UX of VUIs, the extent to which the unambigu-

ous indifferent categorization will persist in the future

remains to be seen.

5.2 Non-Significant Categories

Besides the UX aspects that are significantly catego-

rized into a Kano category, we identified ten UX as-

pects that are not rated clearly enough to be assigned

to a Kano category for any age group. Five of them

have a Total Strength value above or equal the thresh-

old of importance of 90%. The vast majority of par-

ticipants consider them to be very important; hence,

they should be considered when developing VUIs.

For example, the Total Strength values of

Longevity and Reliability range between 93% and

96%, which meets the threshold of importance. Both

UX aspects are almost evenly divided between must-

be and one-dimensional, ranging between 41% and

52% for each of the two Kano categories within the

age groups. Therefore, VUI developers should con-

sider these characteristics for all age groups, even

though they are not significantly categorized.

Link 3rd-Party Products, Range of Functions, and

Innovation have considerably lower Total Strength

values. The Total Strength values of Safety and In-

dependence are slightly higher, but they are still be-

low the threshold of importance. According to our

findings, these five UX aspects do not need special

consideration for any age group.

5.3 Limitations

Our study’s limitations include the non-representative

standard sample distribution due to recruitment

through the Prolific crowdsourcing platform with-

out census data (Prolific Academic Ltd., 2023). In

the prior study, participants were from the USA and

UK. To minimize cultural influences, we included

participants from Canada and Australia and main-

tained consistent study conditions with the previous

research (K

¨

olln et al., 2023a) to mitigate bias.

Although Prolific provides high-quality, reliable

data and participants from diverse populations (e.g.,

in terms of geographic location and ethnicity), the

generalizability of the results is limited because all of

these conditions favor a WEIRD (western, educated,

industrialized, rich, and democratic) sampling bias.

6 CONCLUSION & FUTURE

WORK

We explored the differences between VUI users of

various ages (N = 384) with the KM using both dis-

crete analysis and continuous analysis. The age seg-

mentation showed that VUI users of different ages

are more alike than different. Hence, although VUI

developers should take into account context-specific

user requirements, there are no major age effects in

our data set. Future work will examine data from non-

WEIRD countries that are distinctly different from the

chosen ones. In summary, using Kano to gather more

information about VUI users of different ages has

been valuable and could be further applied on other

characteristics as well.

REFERENCES

Ammari, T., Kaye, J., Tsai, J. Y., and Bentley, F. (2019).

Music, search, and iot: How people (really) use voice

assistants. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact., 26.

There Are no Major Age Effects for UX Aspects of Voice User Interfaces Using the Kano Categorization

337

Berger, C., Blauth, R., Boger, D., Bolster, C., Burchill, G.,

DuMouchel, W., Pouliot, F., Richter, R., Rubinoff, A.,

Shen, D., Timko, M., and Walden, D. (1993). The de-

sire for continuous and graphical analysis. In Berger,

C., Blauth, R., Boger, D., Bolster, C., Burchill, G.,

DuMouchel, W., Pouliot, F., Richter, R., Rubinoff, A.,

Shen, D., Timko, M., and Walden, D., editors, Kano’s

methods for understanding customer-defined quality,

volume 2.4, pages 17–20. Center for Quality Manage-

ment Journal.

BVDW (2017). Digital Trends Umfrage zu digitalen

Sprachassistenten (Digital Trends survey on digital

voice assistants).

Chaouali, W., Yahia, I. B., Lunardo, R., and Triki, A.

(2019). Reconsidering the “what is beautiful is good”

effect. International Journal of Bank Marketing.

Chen, C.-C. and Chuang, M.-C. (2008). Integrating the

kano model into a robust design approach to enhance

customer satisfaction with product design. Interna-

tional Journal of Production Economics, 114(2):667–

681. Special Section on Logistics Management in

Fashion Retail Supply Chains.

Czaja, S. J., Charness, N., Fisk, A. D., Hertzog, C., Nair,

S. N., Rogers, W. A., and Sharit, J. (2006). Factors

predicting the use of technology: findings from the

center for research and education on aging and tech-

nology enhancement (CREATE). Psychology and ag-

ing, 21(2):333–352.

DuMouchel, B. (1993). Thoughts on graphical and con-

tinuous analysis for kano’s methods. In Berger, C.,

Blauth, R., Boger, D., Bolster, C., Burchill, G., Du-

Mouchel, W., Pouliot, F., Richter, R., Rubinoff, A.,

Shen, D., Timko, M., and Walden, D., editors, Kano’s

methods for understanding customer-defined quality,

volume 2.4, pages 20–23. Center for Quality Manage-

ment Journal.

Erikson, E. H. (1994). Identity: Youth and Crisis. Norton

& Company.

Fong, D. (1996). Using the self-stated importance question-

naire to interpret kano questionnaire results. Center

for Quality Management Journal, 5:21–23.

Haimes, P. (2021). Beyond beauty: Towards a deeper under-

standing of aesthetics in hci. In Extended Abstracts of

the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Com-

puting Systems, CHI EA ’21, New York, NY, USA.

Association for Computing Machinery.

Jenkins, A., Eslambolchilar, P., Lindsay, S., Hare, M.,

Thornton, I., and Tales, A. (2016). Attitudes to-

wards attention and aging:: What differences between

younger and older adults tell us about mobile technol-

ogy design. International Journal of Mobile Human

Computer Interaction, 8:47–68.

Kano, N., Seraku, N., Takahashi, F., and Tsuji, S.-i. (1984).

————— (attractive quality and must-be quality).

Journal of the Japanese Society for Quality Control,

31(4):147–156.

Klein, A. M., Deutschl

¨

ander, J., K

¨

olln, K., Rauschenberger,

M., and Escalona, M. J. (2023a). Exploring the Con-

text of Use for Voice User Interfaces: Toward Context-

dependent UX Quality Testing. Journal of Software:

Evolution and Process. [Accepted].

Klein, A. M., Hinderks, A., Rauschenberger, M., and

Thomaschewski, J. (2020a). Exploring voice assistant

risks and potential with technology-based users. In

Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on

Web Information Systems and Technologies - Volume

1: WEBIST,, pages 147–154. SciTePress.

Klein, A. M., Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., and

Thomaschewski, J. (2020b). Construction of

ueq+ scales for voice quality. In Proceedings of the

Conference on Mensch Und Computer, pages 1–5.

Association for Computing Machinery.

Klein, A. M., Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., and

Thomaschewski, J. (2020c). Measuring user ex-

perience quality of voice assistants. In 2020 15th

Iberian Conference on Information Systems and

Technologies (CISTI), pages 1–4. IEEEE.

Klein, A. M., K

¨

olln, K., Deutschl

¨

ander, J., and Rauschen-

berger, M. (2023b). Design and Evaluation of Voice

User Interfaces: What should one consider? In

Design, Operation and Evaluation of Mobile Com-

munications: 4th International Conference, MOBILE

2023, Held as Part of the 25th HCI International Con-

ference, HCII 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark, July 23-

28, 2023, Proceedings, pages 167–190.

Klein, A. M., Rauschenberger, M., Thomaschweski, J., and

Escalona, M. J. (2021). Comparing voice assistant

risks and potential with technology-based users: A

study from germany and spain. Journal of Web En-

gineering, 20 − 7.

K

¨

olln, K., Deutschl

¨

ander, J., Klein, A., Rauschenberger,

M., and Winter, D. (2022a). Identifying user expe-

rience aspects for voice user interfaces with inten-

sive users. In Proceedings of the 18th International

Conference on Web Information Systems and Tech-

nologies, pages 385–393. SCITEPRESS - Science and

Technology Publications.

K

¨

olln, K., Deutschl

¨

ander, J., Klein, A. M., Rauschenberger,

M., and Winter, D. (2022b). Protocol for identifying

user experience aspects for voice user interfaces with

intensive users.

K

¨

olln, K., Klein, A. M., Deutschl

¨

ander, J., Winter, D., and

Rauschenberger, M. (2023a). Categorizing ux aspects

for voice user interfaces using the kano model. In

Marchiori, M., Dom

´

ınguez Mayo, F. J., and Filipe, J.,

editors, Web Information Systems and Technologies,

pages 209–228. Springer Nature Switzerland.

K

¨

olln, K., Klein, A. M., Deutschl

¨

ander, J., Winter, D., and

Rauschenberger, M. (2023b). Protocol for categoriz-

ing ux aspects for voice user interfaces using the kano

model.

Lee, C. and Coughlin, J. (2014). Perspective: Older adults’

adoption of technology: An integrated approach to

identifying determinants and barriers. Journal of

Product Innovation Management, 32.

Lee, M. C. and Newcomb, J. F. (1997). Applying the kano

methodology to meet customer requirements: Nasa’s

microgravity science program. Quality Management

Journal, 4(3):95–106.

Lis, J. (2022). How big is the voice assistant market? Ac-

cessed 26-May-2023.

WEBIST 2023 - 19th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

338

Mitzner, T. L., Boron, J. B., Fausset, C. B., Adams, A. E.,

Charness, N., Czaja, S. J., Dijkstra, K., Fisk, A. D.,

Rogers, W. A., and Sharit, J. (2010). Older adults talk

technology: Technology usage and attitudes. Comput-

ers in human behavior, 26(6):1710 – 1721.

Palan, S. and Schitter, C. (2018). Prolific.ac a subject pool

for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Ex-

perimental Finance, 17:22–27.

Peer, E., Rothschild, D., Gordon, A., Evernden, Z., and

Damer, E. (2021). Data quality of platforms and pan-

els for online behavioral research. Behavior Research

Methods, 54:1643–1662.

Pradhan, A., Lazar, A., and Findlater, L. (2020). Use of

intelligent voice assistants by older adults with low

technology use. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact.,

27(4).

Prolific Academic Ltd. (2023). Accessed 06-Mar-2023.

Rauschenberger, M. (2021). Acceptance by Design : Voice

Assistants. In 1st AI-DEbate Workshop : work-

shop establishing An InterDisciplinary pErspective on

speech-BAsed TEchnology, page 27.09.2021, Magde-

burg, Germany. OvGU.

Sauer, J. and Sonderegger, A. (2022). Visual aesthetics

and user experience: A multiple-session experiment.

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,

165:102837.

Sigelman, C. K. and Rider, E. A. (2008). Life-Span Hu-

man Development. Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 6.

edition.

Song, Y., Yang, Y., and Cheng, P. (2022). The investiga-

tion of adoption of voice-user interface (vui) in smart

home systems among chinese older adults. Sensors,

22:1614.

Strassmann, C., Kr

¨

amer, N. C., Buschmeier, H., and Kopp,

S. (2020). Age-Related Differences in the Evaluation

of a Virtual Health Agent’s Appearance and Embod-

iment in a Health-Related Interaction: Experimental

Lab Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research,

22:e13726.

Tas¸, S., Hildebrandt, C., and Arnold, R. (2019). Voice As-

sistants in Germany. WIK Wissenschaftliches Institut

f

¨

ur Infrastruktur und Kommunikationsdienste GmbH.

Timko, M. (1993). An experiment in continuous analy-

sis. In Berger, C., Blauth, R., Boger, D., Bolster, C.,

Burchill, G., DuMouchel, W., Pouliot, F., Richter, R.,

Rubinoff, A., Shen, D., Timko, M., and Walden, D.,

editors, Kano’s methods for understanding customer-

defined quality, volume 2.4, pages 17–20. Center for

Quality Management Journal.

Townsend, D., Knoefel, F., and Goubran, R. (2011). Pri-

vacy versus autonomy: A tradeoff model for smart

home monitoring technologies. In 33rd Annual In-

ternational Conference of the IEEE Engineering in

Medicine and Biology Society, pages 4749–4752.

IEEE.

Tractinsky, N., Katz, A., and Ikar, D. (2000). What is beau-

tiful is usable. Interact. Comput., 13:127–145.

Vimalkumar, M., Sharma, S. K., Singh, J. B., and Dwivedi,

Y. K. (2021). ’Okay google, what about my privacy?’:

User’s privacy perceptions and acceptance of voice

based digital assistants. Computers in Human Behav-

ior, 120:106763.

Witell, L., L

¨

ofgren, M., and Dahlgaard, J. J. (2013). Theory

of attractive quality and the Kano methodology the

past, the present, and the future. Total Quality Man-

agement & Business Excellence, 24:1241 – 1252.

Zhong, R., Ma, M., Zhou, Y., Lin, Q., Li, L., and Zhang,

N. (2022). User acceptance of smart home voice as-

sistant: a comparison among younger, middle-aged,

and older adults. Universal Access in the Information

Society.

There Are no Major Age Effects for UX Aspects of Voice User Interfaces Using the Kano Categorization

339