Cadets’ Psychological Readiness Formation Program in the National

Guard of Ukraine to Use Firearms in Professional Spheres

Ihor O. Atamanenko

1 a

, Oksana K. Kornosenko

2 b

, Oksana V. Danysko

2 c

and

Maya S. Serhiienko

3 d

1

The National Academy of the National Guard of Ukraine, 3 Zakhysnykiv Ukrainy Sq., Kharkiv, 61001, Ukraine

2

Poltava V. G. Korolenko National Pedagogical University, 2 Ostrohradskoho Str., Poltava, 36003, Ukraine

3

Donbas State Pedagogical University, 19 Henerala Batiuka Str., Sloviansk, 84116, Ukraine

Keywords:

Psychological Readiness, Firearms Training, Military Personnel, Combat Readiness, Stress Management,

Emotion Regulation, Self-Regulation, Autonomic Nervous System, Heart Rate, Respiration Rate, Extreme

Conditions, National Guard of Ukraine, Nervous System Strength, Psychological Skills Training.

Abstract:

The imperfection of psychological training methods and psychological training programs of cadets of the

National Guard of Ukraine (NGU) determines the study’s relevance. The study’s purpose is to develop and

implement a program of psychological training for firearms use during the training process of NGU cadets; to

diagnose the activity of the departments of the autonomic nervous system, according to indicators: heart rate

and breathing rate; to reveal or refute the correlation between the strength of the nervous system and the success

level of NGU cadets during training shooting; to examine the program’s effectiveness in maintaining and

strengthening the nervous system force of cadets. Methods of research include analysis, synthesis, modeling,

programming, pedagogical observation, and methods of expert evaluation. The program consists of three

stages: motivational, basic, and restoring, and aims at forming a positive motivation to use firearms in extreme

conditions, improving the state of pre-situational readiness, optimal combat state, and transition from one

state to another, and working out the action strategy under the influence of stressful factors during service and

combat activity. After differentiating the heart rate and breathing data for all groups, a relationship between the

level of cadets’ psychological readiness and indicators of autonomic changes was revealed: on average, 50%

of the total number of cadets are individuals who have accelerated breathing and heart rate during the period

of shooting conditions, with 46% of them are groups with an average and low level of success in shooting. The

psychological training program is effective in supporting and strengthening the cadets’ strong nervous system,

but only a marginally weak one.

1 INTRODUCTION

A full-scale war on the territory of Ukraine increased

the resource needs for weapons and human capi-

tal. The high level of Ukrainian militaries motiva-

tion is due to a personal and patriotic desire to liber-

ate Ukrainian lands from Russian invaders. However,

the emotional passion caused by the rage of Ukrainian

militaries towards the occupiers can negatively affect

the course of events in stressful situations. There-

fore, the important factor in the professional training

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8959-5423

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9376-176X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4040-562X

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5511-5030

of future officers of the National Guard of Ukraine

(NGU) is the formation of psychological readiness to

use firearms.

The psychological training of military personnel is

a process of purposeful mental qualities formation to

ensure a persistent performance of combat and service

tasks in various conditions. The effectiveness of pro-

fessional readiness should be evaluated by the tempo-

ral, quantitative, and qualitative indicators of speci-

fied task realization, certainly, and certainly to include

as a component methods and actions in the conditions

of stress factors simulation, which is typical for actual

circumstances of extreme service and combat task re-

alization. According to the requirements, the profes-

sional training of officers (NGU) should be conducted

like a simulated combat mission, and all stressful fac-

Atamanenko, I., Kornosenko, O., Danysko, O. and Serhiienko, M.

Cadets’ Psychological Readiness Formation Program in the National Guard of Ukraine to Use Firearms in Professional Spheres.

DOI: 10.5220/0012646000003737

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning (ICHTML 2023), pages 31-40

ISBN: 978-989-758-579-1; ISSN: 2976-0836

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

31

tors that may hypothetically appear during the service

and combat activity should be considered. During the

psychological training, it is important to teach future

officers to act in perceived danger situations, to over-

come stress, and to take reasonable risks. At the same

time, it should be noted that the professional training

system of NGU future officers does not fully take into

account the influence of individual and psychologi-

cal features of military personnel on the service and

combat activity. The methods of forming psycholog-

ical readiness for the firearms using have also been

researched in part.

The experience of teaching and military activ-

ity allowed us to detect deficiencies of psychological

training, i.e.:

• the psychological training is not highlighted as an

independent type of training, so it does not pro-

vide an opportunity to use it taking into account

the peculiarities of the NGU future officers’ psy-

chology and their behavioral reactions;

• the methods of training NGU future officers were

artificially limited;

• the necessary to form the individual psychological

qualities among cadets is ignored;

• the tactical features of NGU cadets’ actions in ex-

treme conditions are not taken into account during

working out the practical part of task training.

To solve the outlined problems it is necessary to

form several research tasks:

1. To develop, justify, and implement in the profes-

sional training of the NGU cadets a program to

form a psychological readiness for firearms use.

2. To diagnose the activity of the autonomic nervous

system, such as heart rate and breathing rate, dur-

ing firing from a Makarov pistol.

3. To reveal or refute the correlation between the

strength of the nervous system and the level of

NGU cadets’ success at the time of using firearms

during training shootings.

4. To check the program regarding the possibilities

of supporting and strengthening the nervous sys-

tem force of cadets for effectiveness.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The analysis of the latest publications, according

to this study topic, indicates a high level of inter-

est among scientists to the problem of psychologi-

cal readiness of military personnel during the per-

formance of service and combat tasks, in particular,

behavioral and physiological reactions in a state of

stress. In particular, Sekel et al. (2023) note that

the military tactical adaptive decision-making during

the simulations of military operational stress depends

on personality, resilience, aerobic, and neurocognitive

functions. Laboratory studies based on the simulation

of combat operations or a military field training dura-

tion of 48 hours. Laboratory studies experimentally

prove that military operational stress negatively influ-

ences the physical, cognitive, and emotional soldier’s

efficiency during simulation, in particular, the adop-

tion of military tactical adaptive decisions.

Koltun et al. (2023) identify the physiological

and psychological stressors that may impair military

readiness and military efficiency during military train-

ing and under operational conditions. During the ex-

periment we had the obtained data. According to it,

we may point out that military personnel, who are in

a state of stress, lose their ability to the aerobic en-

durance and adequate decision-making, i.e., reduce

their cognitive performance.

Flood and Keegan (2022) note that military per-

sonnel often perform complex cognitive operations

under unique conditions of high stress. Cognitive im-

pairment as a result of this stress can have serious

consequences for the success of military operations

and the well-being of military personnel, especially

in combat environments. Therefore, during military

training, it needs to understand the feeling, stress re-

sistance, and the degree of impaired cognitive func-

tions. The study highlights the experience of over-

coming psychological stress among military person-

nel in the framework of the transactional theory of

stress.

Nassif et al. (2021) notes that mental skills, such

as focus and emotion management, are essential for

optimal performance in high-stress occupations, in-

cluding the military. To examine the impact of mind-

fulness training on operational performance, mental

skills, and psychological health, a short-form pro-

gram, Mindfulness-Based Attention Training, was de-

livered to active duty soldiers as part of two random-

ized trials. As a result, the proposed program turned

out to be effective and suitable to optimize the op-

erational indicators of the body’s response to stress

factors and improve mental skills in military forces.

Lytvyn and Rudenko (2021) give grounds for the

necessity of introducing into the educational process

of higher educational institutions of the State Emer-

gency Service the pedagogical system of formation

of cadets’ readiness for professional activity and the

expediency of creating appropriate psychological and

pedagogical conditions for increasing the effective-

ness of this process (continuous improvement of the

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

32

pedagogical skills of the teaching staff; active use of

innovative service and combat experience of fire and

rescue formations; improving psychological training

by modeling stressors that affect personnel in haz-

ardous circumstances and extreme situations; taking

into account the individual psychological character-

istics of cadets; moral and material stimulation of

cadets’ activity in ordinary and, especially, in extreme

situations related to risk to life), aimed at ensuring

their optimal preparedness to work in risky (extreme)

circumstances.

Taylor et al. (2011) call attention of the scien-

tific community to the problem of training psycho-

logical skills in a military survival school. A ran-

domized field research aimed to examine the effects

of short-term stress training to teach arousal control

through self-talk in individual 40-minute sessions.

Stress symptoms were then assessed during a mock-

captivity phase of training, as well as 24 hours, 1

month, and 3 months after completion of training.

Survival training precipitated remarkable increases in

subjective distress, but few substantive group differ-

ences emerged.

We were greatly interested in the article by Mc-

Crory et al. (2013). The study tested the hypothesis

that multimodal psychological skills training would

increase the self-regulatory behavior of military pi-

lot trainees. The results showed linearity according

to the improvement of specific self-regulation. Simi-

larly, there was a significant increase in self-efficacy

and psychological skills use, as well as, a concomi-

tant decrease in anxiety and worry, highlighting the

potential for modifying the cognitive and behavioral

strategies of pilot trainees to maintain motivation to

learn and improve individual/group responsiveness.

Kolesnichenko et al. (2016) investigated the psy-

chological readiness of the servicemen of the National

Guard of Ukraine to take risks, in particular, substan-

tiated its content and structure, characterized the lev-

els that are the basis of the psychodiagnostic method-

ology. The methodology has such scales as the man-

ifestation of willpower, military camaraderie, profes-

sional identity, and self-control and meets the require-

ments of reliability and validity.

Kyrychenko (2020) highlights different ap-

proaches of researchers to solve the problem of

servicemen’s psychological readiness of airborne

assault troops to conduct combat operations. Based

on the analysis of the conditions and specific using

of airborne assault troops, the peculiarities of the

servicemen’s psychological readiness to operate in

combat conditions were analyzed.

A detailed analysis of the special literature proves

that the problem of forming psychological readiness

among the military personnel is an actual one. A sig-

nificant scientific contribution of scientists reveals the

theoretical and methodical features of military per-

sonnel training and their behavioral reactions in the

situation of overcoming stress. However, it should be

noted that the problem of the psychological readiness

forming among future officers of the National Guard

of Ukraine is insufficiently studied and needs to be

addressed in the framework of the weapons using as

the course of training and as the service and combat

task realization.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

To solve the tasks, we developed a program to form

the psychological readiness of NGU cadets to use

firearms in their professional activities. The develop-

ment and implementation of the program required the

use of the following research methods: the analysis

was used to study the special literature and levels of

cadets’ psychological readiness to use weapons; syn-

thesis to integrate the stages of the program and its el-

ements into a single system; the simulation technique

involved the creation of a conditional model of a suc-

cessful cadet who effectively uses weapons for com-

bat task realization; the programming technique was

used to develop the psychological readiness program

for future NGU cadets; pedagogical observation and

oral survey were carried out for systematic analysis

and assessment of individual perception of influence

methods on the future cadet’s mind without interfer-

ing in this process; expert evaluation method.

The expert evaluation method was used to deter-

mine the level of quality of the cadets’ actions, their

mental state, and the results of shooting. According

to the conditions of the shooting course, we surveyed

and divided the respondents into three groups with

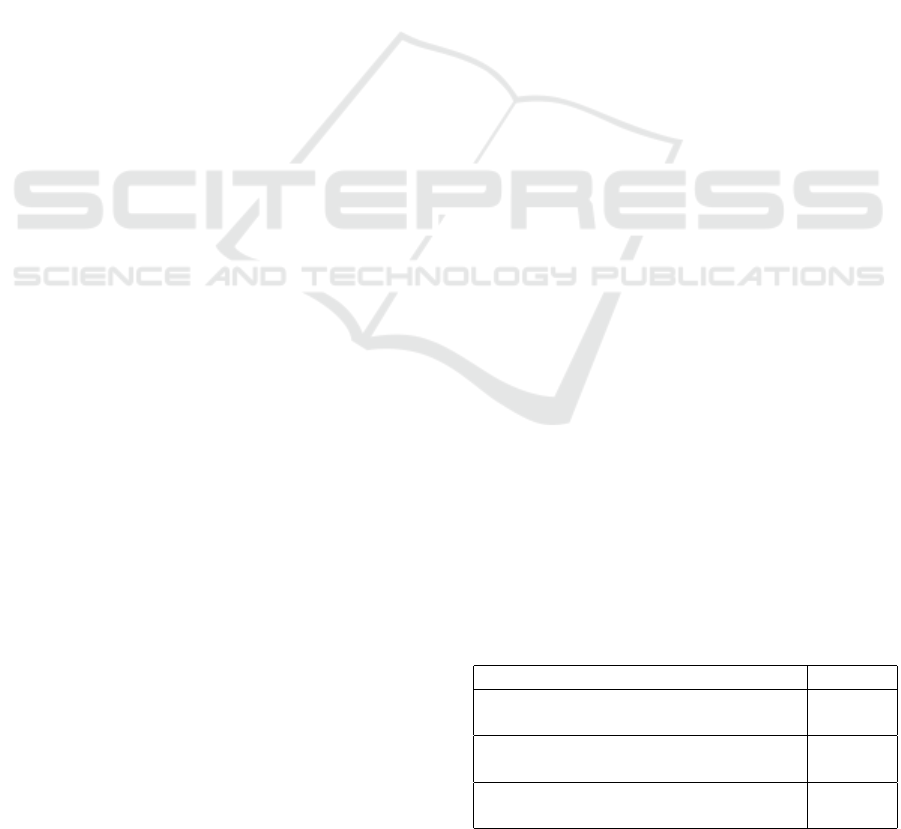

different numbers of people (table 1).

The first group consisted of cadets who showed

high results and received an “excellent” rating for the

exercise. The cadets’ actions in this group were confi-

dence, accuracy, thoughtfulness, and coherence. They

Table 1: Quantitative indicators of the cadets’ distribution

by groups with different levels of success in training exer-

cises with a Makarov pistol.

Group of cadets Result, %

The first group had a high level of success

in shooting (n = 36)

20

The second group had an average level of

success in shooting (n = 106)

58

The third group had a low level of success

in shooting (n = 40)

22

Cadets’ Psychological Readiness Formation Program in the National Guard of Ukraine to Use Firearms in Professional Spheres

33

were attentive and focused on performing training ex-

ercises with the Makarov pistol while receiving the

task and its execution. The second group of cadets

showed average results and received a “good” or “sat-

isfactory” rating during the exercise. Minor mistakes

were observed in their actions, but outwardly, men-

tal tension was visible. The third group consisted of

cadets who showed low results and received “satis-

factory” and “unsatisfactory” grades during the exer-

cise. Representatives of this group made serious mis-

takes during practice shooting with the Makarov pis-

tol. They were unable to execute the firing instructor’s

commands due to lack of confidence and attention.

The cadets were distinguished visually by their pro-

nounced paleness, dilated pupils and eyes, and physi-

cal weakness.

We carried out a diagnosis of the activity of the

departments of the autonomic nervous system in the

cadets in the process of conducting activities to check

the implemented program of psychological training.

Such indicators as heart rate and respiratory rate were

diagnosed. Diagnostics of indicators were carried out

in three stages (the first was before the start of the

shooting, the second was during the shooting, and the

third was 20 minutes after the shooting). The im-

plementation of the experimental program was car-

ried out during the training of senior cadets for 6

months (September, October, and November 2022

and March, April, and May 2023).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of our research point out it is necessary

to provide measures that fully cover the formation of

psychological training components for future officers

to use weapons in combat conditions during the psy-

chological training process. Such an approach can

be implemented only with the systematic planning of

psychological training, which, from our opinion of

view, is possible during the preparation of a program

that includes measures to influence emotional, moti-

vational and intellectual components, and the level of

personal anxiety.

Psychological shooter training is an educational

process aimed to form an optimal psychological state

and persistent internal readiness for the effective use

of firearms, with uncertain conditions of psychologi-

cal and traumatic factors. The process of psychologi-

cal training focuses on the formed following qualities

of the NGU future officers:

• the ability to influence oneself, to abstract from

various extraneous factors that interfere to make

an accurate shot;

• the ability to concentrate one’s attention, to focus

on the main shooting aim, i.e. hitting the target;

• the self-confidence, perseverance, resourceful-

ness, initiative;

• the resistance of the central nervous system to the

influence of stress factors;

• the ability to use autogenic and ideomotor tech-

niques to relieve emotional tension.

Implementation of the training program outlines

the most training lessons in the field, during tacti-

cal, special, and firearms training. For this, an in-

structor should acquire the interdisciplinary knowl-

edge and skills. These tasks are solved during the

NGU cadets’ psychological readiness formation to

use firearms. Based on these tasks, three periods of

the program were defined: I – motivational; II – main;

III – restorative.

The first period is motivational, the following

tasks are:

• to determine the initial level of psychological

readiness formation of NGU cadets in the period

using firearms and differentiate them into groups

with low, medium and high levels;

• to form positive motivation, the necessary atti-

tudes for training according to the development of

psychological readiness for firearms using;

• to increase the cadets’ ability to relax, to mutually

transition from a wait state to alert status;

• to contribute to the development of cadet’s self-

identification and self-determination, the reasons,

goals and tasks for the of the Special Combat Task

execution;

• to reveal the hidden possibilities of the human

mind and ways of managing them;

• to form among the cadets a system of initial

concepts and knowledge regarding psychological

readiness to use firearms in the service and com-

bat conditions and methods of increasing its effec-

tiveness.

The main purpose of this period is the formation

of cadets’ positive motivation in regarding the forma-

tion of their psychological readiness to use firearms

in extreme conditions. This purpose should be related

to the development of cadets’ sustainable motivation

and self-education and self-improvement interest dur-

ing firearms and physical training classes; to trust

the teacher who conducts classes; strong discipline

during training and strong self-discipline during the

self-preparation; to ensure psychologically comfort-

able microclimate in the group. Professional psychol-

ogists and instructors who have experience in using

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

34

firearms in extreme conditions should be conducted

of classes.

One of the important tasks at the first period is

the formation of future officers’ skills in voluntary

mental self-regulation, during the group training and

self-preparation after the classes. It is necessary to

hold lectures to explain cadets the peculiarities of mil-

itary activity, possible negative consequences of the

stress factors influence that are linked with this activ-

ity, methods and methods that allow to increase re-

sistance to the influence of psychological traumatic

factors and ways to preserve the ability to work in

extreme situations. The topics of lectures should

have a professional and applied psychological orien-

tation: “Specifics of extreme conditions during mili-

tary and combat activity of NGU officers”, “Psycho-

logical readiness of NGU officers to use weapons in

conditions of military and combat activity”, “Tech-

nologies of NGU officers activity during the firearms

using in extreme conditions”, “Methods and means

of mental self-regulation in periods of negative emo-

tional states caused by the performance of military

and combat activity”, etc.

It is necessary to hold lectures to explain cadets

the importance of the ability to resist the negative im-

pact of stress factors and the need to improve psycho-

logical resistance to the use of firearms in the condi-

tions of service and combat activity. After a series

of lectures, cadets should be recommended to inde-

pendently improve the techniques and skills of men-

tal regulation of adverse emotional states, as well as

familiarize themselves with special literature.

The techniques and methods of mental regulation

in the situation of adverse psychological states for

the formation of the skills of voluntary self-regulation

and self-control, the state of pre-situational psycho-

logical readiness for action should be studied by

cadets after the lecture course. The method of neu-

romuscular relaxation proposed by Jacobson (1925)

is used for training. The purpose of Jacobson’s pro-

gressive muscle relaxation is to induce a relaxation

response. The method helps to relax the body and

change the active state of the body to a calm one. The

learning process consists of three periods. In the first

stage, cadets learn to realize and feel weak muscle

tension and purposeful relaxation of the muscles re-

sponsible for bending all parts of the body. In the

second stage, cadets learn differentiated relaxation to

relax muscles that are not involved in supporting the

body in a vertical position (stabilizer muscles). At the

third stage, cadets learn to purposefully reduce and

then remove local muscle tension, to transition from a

state of waiting to combat readiness in extreme situa-

tions.

The initial training period must be carried out with

the head of training to increase the training effective-

ness and avoid mistakes. Cadets will learn about the

principles of mental self-regulation: operational inde-

pendence, and striving for improvement before con-

ducting classes using this method. It is clarified the

reason for the need to be able to concentrate and keep

one’s attention on the object, to keep a visual image

concentrated in one’s imagination, to feel and imag-

ine the actions of verbal formulations, to arbitrarily

relax the muscles, to influence oneself at the moment

of lowering the level of mental tension. Cadets should

pay attention to the general algorithm of actions; in

this algorithm, each cadet can change individual ele-

ments, and include his own techniques in it to effec-

tively use personally for himself. Techniques will be

useful under conditions that correspond to a specific

mental state. Therefore, it is important to be able to

understand, analyze and remember your mental state,

using any reference points for this: heart rate, muscle

sensations, breathing rate, etc.

The total duration of the full training cycle by this

method is 20-25 minutes. Depending on the improve-

ment of voluntary mental self-regulation skills, the

class time should be reduced to 15 minutes. Fur-

ther consolidation of abilities and skills is carried

out in conditions of emotional stimulation and emo-

tionally intense critical situations. In particular, the

teacher takes the future officers to the firing line,

where he asks the cadets to enter a state of relaxed

pre-situational readiness. The leader should conduct

a briefing to explain that every loud shot will be re-

sponded to inside the body by involuntary muscle

contractions, and this is normal. Such instruction is

undertaken before the technique practiced by each

cadet. Cadets must learn to relax quickly, without

unnecessary movements, giving themselves a condi-

tioned signal and producing a conditioned reflex. At

the end of the briefing, the teacher notes that as soon

as the cadets reach a state of mental calm, they should

slowly approach the firing line and maintain relax-

ation in movement.

At this stage, the teacher focuses the cadets’ at-

tention on breathing and inspecting their body, the

need to work out the conditioned signal, and requires

them to slowly approach it after entering a state of

relaxation, trying not to disturb it. After the cadets

have completed the exercise, the teacher offers each

of them to define a trigger, a trigger signal, for enter-

ing this state. The trigger can be of any form, that is,

a bodily gesture, a feeling, a position, a squeeze, or

anything associated with the desired state. It can be

a sound, a verbal formula, a visual picture, a set of

movements, etc. After each cadet has chosen a trig-

Cadets’ Psychological Readiness Formation Program in the National Guard of Ukraine to Use Firearms in Professional Spheres

35

ger for himself, he is invited to independently practice

entering the state and maintaining it against the back-

ground of powerful sound stimuli (shooting is taking

place nearby). Then you need to check the acquisition

of the shooting skill with a Makarov pistol, standing

25 m from the target.

The criteria of the skills’ formation at this period

are a clear attitude and positive motivation for the

formation of psychological resistance to the use of

firearms; persistent interest in self-development and

self-improvement; the ability to arbitrarily relax mus-

cles, reduce mental tension; the ability to arbitrarily

induce a state of calmness, mobilization of forces;

the ability to transition from a state of rest to combat

readiness.

The second period is the main stage, which be-

gins after the cadets have mastered the techniques

of mental self-regulation. This stage involves con-

solidating the abilities and skills acquired in the first

stage, improving the state of pre-situational readiness,

optimal combat state, and transition from one state to

another, working out the strategy of actions under the

influence of psycho-traumatizing factors of service-

combat activity.

At this period, the following tasks are solved:

• to teach cadets to reproduce the state of pre-

situational readiness for emotionally tense condi-

tions of using firearms;

• to improve the skill of arbitrary self-regulation of

emotional states, ideomotor ideas about the future

use of firearms in extreme situations;

• to work out the strategy of using firearms in the

conditions of realization service and combat tasks.

This stage begins with the improvement of cadets’

skills of voluntary self-regulation of emotional states,

ideomotor ideas about the future use of firearms in

combat conditions.

The development of reflection and the ability to

exercise self-control allows you to purposefully study

the pre-situational state of readiness for the influ-

ence of emotional factors. The pre-situational state of

readiness allows officers to remain emotionally stable

in suddenly arising emotional situations. This con-

dition slows down the growth of tension in case of

prolonged exposure to stress factors. The state of

pre-situational readiness is induced by improving the

techniques of self-suggestion, imagining the perfor-

mance of the following actions that require determi-

nation from the cadet, that is, ideomotor training.

During ideomotor training, it is necessary to ob-

serve the basic rules of its implementation. First, the

more accurately the movement image can be imag-

ined, the more accurate the performed movement will

be. Secondly, the imaginary image of the action must

necessarily be connected with the muscle-joint sen-

sations of the shooter, and the representations can be

visual. In this case, the shooter sees himself as if from

the outside. So, by observing a person’s muscles dur-

ing ideomotor training, you can easily find out how far

his ideas about this or that technical element achieve

the purpose. Thirdly, the effect of the influence rep-

resentations increases markedly if they are combined

with accurate verbal commands and pronunciations.

Accordingly, it is necessary not only to imagine this

or that movement but also to speak its essence out

loud at the same time. In some cases, commands

should be spoken simultaneously with the representa-

tion of the movement, and in other cases, commands

should be spoken before the representation. Only

practice will show which method to choose. The fact

that words significantly enhance the effect of repre-

sentation can be verified during the test with a finger

on which an object hangs. If you not only imagine

that the object starts to swing, let’s say, forward, but

start saying the word “forward” out loud, then the am-

plitude of the oscillations will immediately increase.

Fourthly, to learn a new element of technique, it is

necessary to imagine it at a slow tempo. A slow repre-

sentation of the movement will allow you to imagine

all the details of the studied gesture and warn of possi-

ble errors in time. Fifth, in order to learn a new techni-

cal element, it is necessary to imagine it in a position

that is close to the spatial position of the body during

its actual performance. So, when a person engages

the ideomotor training and at the same time adopts

a pose that is closest to the real one, more impulses

from muscles and joints to the brain occur to detail

the motor action. It is easier for the brain, which pro-

grams the correct ideomotor representation of move-

ment, to coordinate execution with the musculoskele-

tal system. There is an opportunity to practice the

necessary technical element more consciously. That

is why simulators are useful. This type of exercise

allows one to take a variety of poses, especially the

movements that often take place outside after break-

ing away from the fulcrum. Having been in a state

of imagined weightlessness, a person improves feel-

ing the movement technique and imagines these de-

tails better. Sixth, the ideomotor movement reproduc-

tion sometimes is performed so vividly and expres-

sively that the person involuntarily begins to move,

which indicates the establishment of a strong connec-

tion between the two systems: programming and ex-

ecuting. Such a process is useful because the body

is included in the execution of the movement which

is born in consciousness. That is why, when ideomo-

tor representations are not realized immediately, and

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

36

complications can be a part of the process, it is recom-

mended to consciously join the ideomotor represen-

tations with the corresponding body gestures, and in

this way, connect the imaginary image of the gesture

with the muscles that perform it. In this way, a per-

son can join the unsubstantial character of the move-

ment with the muscles that perform it. Imitations are

also important. The imitation of movement can form

a more precise choice of a certain technical element,

teaches to choose the necessary element to refer first

to the sensations in the muscles, then to the impact of

the brain. Therefore, the imitation of various move-

ments, for example, during warm-up, is an effective

help in preparing for the performance of this or that

complex exercise. But, a mandatory condition for im-

itation is the realization of physical movements and

their simultaneous imagination. If you think about

something else during the simulation, it will not be

useful. Seventh, it is wrong to believe that the final

result comes immediately before the exercise, this is

one of the common mistakes. If you focus only on

the result, you can forget the way to achieve this re-

sult, that is, lose the main thing in the process. That

is, if the shooter thinks that he needs to hit the target,

this thought can prevent him from remembering those

technical elements without which it is impossible to

hit. That’s why he doesn’t hit. In such cases, they

say “overdid” and forget to achieve the get purpose,

they should think not about the final result but about

the imaginary gestures of those actions that can help

to realize it. So, the essence of the ideomotor train-

ing principle is the ability to imagine its ideomotor

specificity before performing the body movement and

accurately assess this movement.

After conducting ideomotor training, NGU’s

cadets must learn to change their state of conscious-

ness. A teacher accents that the optimal state of con-

sciousness is a state of relaxed expectation. At the

preparatory stage, cadets had already worked out the

state of relaxed expectation. At the main stage, it

is necessary to acquire the skills of transition from a

state of relaxed expectation (pre-situational readiness)

to a combat (working) state.

The combat (working) state is an individual state

of consciousness for each officer or cadet that corre-

sponds to external conditions. This condition must

meet certain general criteria.

1. To ensure maximum effective work of a cadet in

circumstances of external factors.

2. To go into combat mode and perform actions

without the use of any stimulating factors.

3. To stay in this psychological state should not harm

a person’s psyche and physiology.

According to the criteria, the condition should not

be affective in nature, i.e. not have a strong emotional

connotation. The cadet must have experience enter-

ing and exiting the combat readiness state at the stage

of professional training. An instructor should instruct

the cadets, and then practice the “combat state” exer-

cise with the cadets. During this period, the training

is performed 6-8 times. During the lesson, cadets’

states may change several times in different situa-

tions. Then the teacher offers the group to test skills

that have been formed, i.e. the body state of relaxed

expectation and the optimal combat (working) state

in practice, during the solution of the Special Com-

bat Task. To achieve a positive result, cadets should

do elements of tactical and technical, fire, and special

physical training and must make maximum use of the

acquired psychological skills.

The modeling of psycho-traumatic factors and the

practice of action tactics in stressful situations have a

unique role during this period. To reproduce the stress

factors of the Special Combat Task in the practical

work, teachers should use various methods of mod-

eling the stress factors of extreme situations, such as

a) visual, auditory, tactile; b) verbal-symbolic, visual,

computer, training, simulation, and combat.

It is also important to use audio recordings with

the sounds of people, gunshots, sirens, and the noise

of the urban environment, which reproduce the actual

conditions of the Special Combat Task for NGU offi-

cers. Simulations of real conditions of using firearms

should be used in several periods. In the first stage,

a positive motivational environment is created for the

lesson. The authors outline that a motivational atti-

tude is a tendency of cadets to act in a certain way,

necessary for achieving the purpose of the lesson. It

means the cadets’ desire to learn, and their under-

standing of the purpose and content of the lesson. In

addition, during the preparation, an instructive emo-

tional background is created, which contributes to the

emergence of mental tension during the lesson. Dif-

ferent techniques for creating a motivational attitude

can be chosen depending on the psychological factors

of training and combat activity that are planned to be

modeled in the class.

In order to accurately and in detail simulate the

danger factor for training, it is necessary to apply me-

thodical techniques that create an appropriate emo-

tional environment for the activity:

1. Before the training, it is necessary to cite cases

of service and combat activity of NGU service-

men, when low psychological readiness to use

weapons, was a reason for injury or death; it is

necessary to cite examples of decisive and effec-

tive using weapons by officers to get the effective-

Cadets’ Psychological Readiness Formation Program in the National Guard of Ukraine to Use Firearms in Professional Spheres

37

ness of the combat mission and as an indicator of

high psychological readiness during practical ac-

tivities.

2. Teachers can increase the cadets’ interest in the

next lesson in the framework of preparation, de-

tailed instruction, increasing the control of the or-

ders’ execution that is related to the safety rules.

The instruction before lessons should be signifi-

cantly different from all other similar activities.

When cadets have grasped a motivational attitude,

the main part is started, stress factors of the situation

are simulated, and exercises with the use of weapons

are performed.

The third period is the restoring stage and starts

after the end of practical shooting by cadets in ex-

treme conditions i.e. during the main period. By its

content, this period is a complex of measures aimed at

psychological rehabilitation and includes the follow-

ing tasks: to restore physical and mental strength; to

reduce or neutralize the negative stress effects that oc-

curred in the process of firing firearms; to restore the

mental state to contribute the optimal performance of

military service tasks.

The authors point out that psychological recovery

is the process of organized psychological influence

aimed at normalizing the mental state of shooters to

solve training, service, and combat tasks. Psycho-

logically stabilizing work with cadets should begin

with an objective assessment of each cadet’s realiza-

tion of training exercises with a Makarov pistol. To

analyze the actions of the cadets, the teacher focuses

on the right cadets’ actions, analyzes mistakes, and

points out ways to prevent them. The leader pays spe-

cial attention to cadets’ psychological readiness to use

firearms and the formation of mutual transition skills

from the state of waiting to the combat state.

To evaluate the actions of shooters, it is necessary

taking into account the realization indicators of train-

ing shootings and the success of the results for each

person, and also the influence of extreme factors on

the emotional state of the actions. To study the men-

tal state of cadets teacher uses observing and commu-

nicating with them, conducting individual and group

psychological lessons, conversations, oral interviews,

etc.

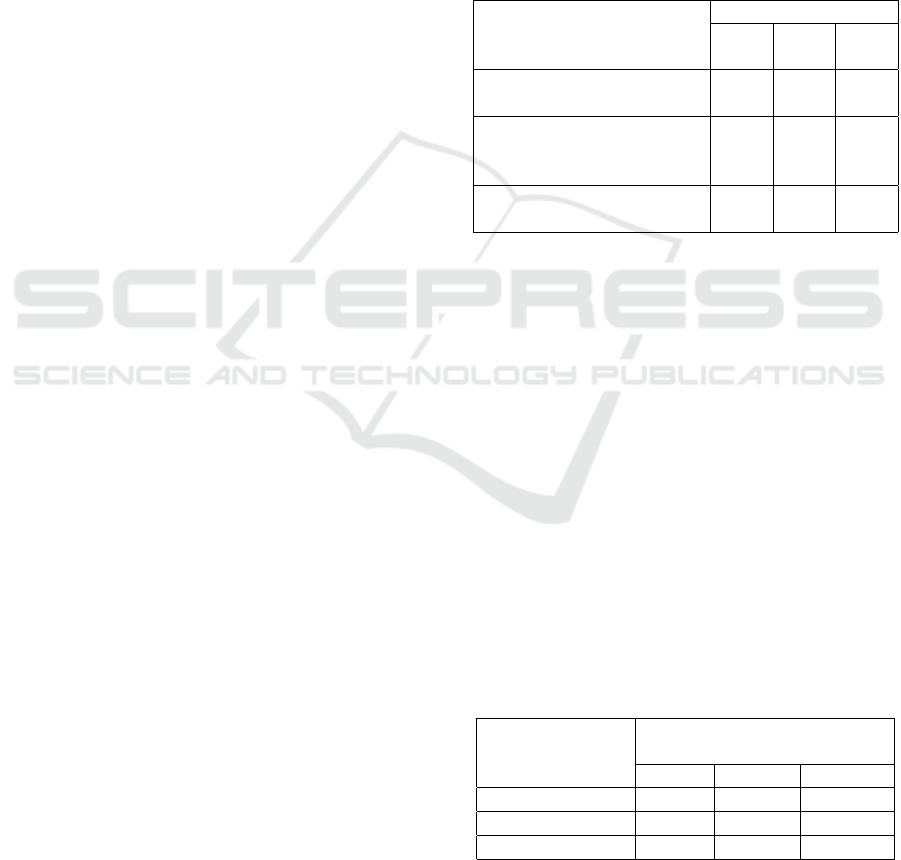

Such indicators as heart rate (table 2) and respira-

tory rate (table 3) were diagnosed during testing the

effectiveness of the program. The diagnosis of these

indicators was carried out in three stages (the first was

before the start of the shooting, the second was dur-

ing the shooting, and the third was 20 minutes after

the shooting).

At the first stage, the average statistical indi-

cators of heart rate in the three examined groups

were respectively: the first group had 73.8 beats/min,

the second had 71.5 beats/min, and the third had

72.2 beats/min, being in the range from 64 to 74.9

beats/min, which corresponds to a state of rest.

At this stage, the cadets experienced average am-

plitude of 10 beats/min of heart rate fluctuations. At

the same time, it exceeded 71 bpm for 75% of cadets.

Calculations showed that the value of variance for the

first cadets’ group is equal to 2.76, the second is 3.22,

and the third is 5.49. The overall index of dispersion

in the three groups of NGU cadets was 3.87 with an

average statistical index of 72.8 bpm.

Table 2: Indicators of heart rate for groups of NGU cadets.

Group of students

Heat rate (bpm)

I

period

II

period

III

period

The first group was highly

skilled in the use of weapons

72.38 94.7 72.49

The second group was aver-

agely skilled in the use of

weapons

70.25 98.5 72.95

The third group was low-

skilled in the use of weapons

71.82 101.3 73.26

Note: p < 0.05

At the second stage, the heart rate of all three

cadets’ groups significantly changed in the direction

of increase. The average statistical indicator was 97

bpm. The heart rate in the studied individuals was

equal to 91 and 107 bpm at the lower and upper lim-

its. The third stage measurement revealed that the

heart rate of almost all cadets stabilized and did not

significantly differ from the initial background values.

The average heart rate was 73.1 bpm. Accordingly, in

the groups of cadets, he scored: for the first group

was 71.9; for the second group was 73.15; for the

third group was 73.62 bpm. The difference in group

readings from the general is not significant. The total

number of examinees, which is 2.22, confirms this.

The next indicator measured during the study was

the respiratory rate (table 3).

Table 3: Respiratory rate indicators for groups of NGU

cadets.

Group of students

Respiratory rate

(breaths per minute)

I period II period III period

I group 14.3 23.4 14.8

II group 13.1 24.01 14.2

III group 13.1 27.9 14.0

Note: p < 0.05

At the first stage, the respiratory rate of all cadets

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

38

was within the normal range. The average statisti-

cal rate in all groups at this stage was 12.73 breaths

per minute. For those examined at this stage, a slight

deviation of personal values from the average statis-

tical indicator is characteristic i.e. of 1.3 breaths per

minute; low amplitude of breath frequency fluctua-

tions ranging from 10 to 16 breaths per minute. The

respiratory rate of cadets of all groups is not signifi-

cantly different, as indicated by this.

At the second stage, the cadets’ respiratory rate

indicators changed, as a result of the firing condi-

tions’ influence. The average statistical indicator for

all groups was 23.5 breaths per minute, which is 12

breaths per minute higher than the average value at the

first stage. The variance according to the data of the

three groups was 7.12, which confirms the increase in

the spread of values by almost 7 units compared to the

first stage.

At the third stage, the values of the respiratory rate

indicator are characterized by a decrease in all cadets

compared to the second stage. The statistical aver-

age of the respiratory rate for the three groups is 14.1

breaths per minute, which hardly exceeds this indi-

cator at the first stage. The total variance is equal to

1.1. At this stage, there are no clearly expressed dif-

ferences in the respiratory rate values of the cadets of

all groups. So, in the first group, the respiratory rate is

13.5 breaths per minute, in the second is 14.2 breaths

per minute, and in the third is 14 breaths per minute.

Intergroup differences were confirmed by math-

ematical calculations of the Student’s t-test, which

gives reason to assert that the data between groups

are statistically reliable.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The principle scheme of forming the psychological

readiness of future NGU cadets to use firearms should

be carried out according to a certain algorithm and

represent a sequence of periods, each of which is a

step to achieve the purpose. At the same time, it is

necessary to comply with the following requirements:

• to practice actions according to the principle of

accessibility: from simple to complex;

• to practice situations using light and noise effects

with recordings of people’s cries for help to per-

form necessary actions and orders without the in-

fluence of the emotional and sensory sphere;

• to introduce non-standard elements into the train-

ing process based on studies of the using firearms

by NGU cadets;

• to conduct psychological training during the fire

training classes based on targeted influence on

components of cadets’ psychological readiness.

The impact of negative emotions on the men-

tal state of NGU cadets is significantly reduced if a

cadet knows which stress factors and difficulties he

may face during military service tasks during service

and combat tasks with firearm use. To improve psy-

chological readiness, it is necessary to accumulate

practical experience to overcome negative emotions

that may arise during combat activities. The great

value has the system of education and training classes,

which is aimed at forming knowledge and skills that

are necessary for making the optimal decision and im-

proving the ability to manage one’s condition in var-

ious situations. Noise habituation is one of the nec-

essary elements in the organization of classes. Noise

exposure causes anxiety and causes errors in behavior

and actions.

Psychological support of service and combat ac-

tivities should prevent the occurrence of such nega-

tive experiences as danger to life, concern for one’s

comrades, discomfort. It should include targeted psy-

chological training; analysis of the behavior of NGU

cadets during practical training of combat activity; as-

sessment of the psychological fatigue degree; to form

a motivation to continue a task realization in extreme

conditions to service and combat activity.

The diagnostics results of the activity of the

cadets’ autonomic nervous system, which was car-

ried out according to indicators such as heart rate and

respiratory rate, gave grounds for conclusions. The

measurement of cadets’ heart rate at the first stage al-

lows us to state that no significant differences were

found between the groups. However, a significant in-

crease in heart rate for all groups of examined cadets

is observed in the second stage. It is caused by the

increased influence of stress factors: excitement, the

results of shooting, and the need to act in specific con-

ditions. It was established that the cadets of the aver-

age and high level groups managed to mobilize their

physical and mental strength to overcome mental ten-

sion at the time of the pistol exercise, their actions

were confident and accurate. For cadets who are not

successful in shooting under these circumstances, a

higher heart rate is characteristic, which, as a rule,

exceeds the indicator of 100 bpm. They were distin-

guished by an accelerated pulse, paleness of the face,

which indirectly indicated great emotional stress. At

the third stage, the heart rate indicators of the second

and especially the third cadets’ groups, who are more

emotionally labile, exceed these indicators of the first

group. According to the E. Gellhorn’s theory, if peo-

ple have increased emotional sensitivity and a high

Cadets’ Psychological Readiness Formation Program in the National Guard of Ukraine to Use Firearms in Professional Spheres

39

level of motivation, they are able to detect the en-

tire complex of vegetative changes in the body for a

longer time (Gellhorn, 1964).

Breathing frequency measurements showed that

cadets of all groups experienced rapid changes at the

second stage. The first group is characterized by uni-

form controlled small breathing, which confirms the

variance, which is equal to 1.89. The second group

is characterized by more frequent breathing. Obser-

vations showed that the breaths of the second group

representatives are deeper and more frequent in their

periodicity than in the first group. The average sta-

tistical frequency of the second group breathing was

24.11 breaths per minute at the second stage. The av-

erage statistical frequency of the third group breathing

turned out to be the highest of the three groups and

amounted to 27.69 breaths per minute at the second

stage. In this group, dispersion is also the largest and

equal to 4.8. This indicates a large difference in res-

piratory rate readings among the cadets of this group.

After studying the heart rate and respiration data

for all groups, the dependence between the level of

cadets’ psychological readiness and the indicators of

vegetative changes was found: on average, 49.8%

of all cadets are individuals who have accelerated

breathing and heart rate during the period of expo-

sure to shooting conditions. Also, 46.7% of cadets

belong to averagely skilled or low-skilled groups in

the shooting.

It was found that examinees, who have a high

force of the nervous system, demonstrate a high level

of successful actions while they use firearms, and ex-

aminees who have a weak force of the nervous sys-

tem, demonstrate a low level of successful actions un-

der the influence of shooting factors. The nervous sys-

tem is exhausted when stress factors affect the human

psyche. According to the results of our research, the

force of the nervous system remains practically un-

changed under the influence of shooting factors, even

with their long-term influence on the human psyche.

Techniques and methods of psychological train-

ing for the NGU cadets allow them to maintain and

strengthen the average force of a nervous system, but

not to have a great influence on strengthening of a

weak nervous system.

REFERENCES

Flood, A. and Keegan, R. J. (2022). Cognitive Resilience to

Psychological Stress in Military Personnel. Frontiers

in Psychology, 13:809003. https://doi.org/10.3389/

fpsyg.2022.809003.

Gellhorn, E. (1964). Motion and Emotion: The Role

of Proprioception in the Physiology and Pathologyof

the Emotions. Psychological Review, 71(6):457–472.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0039834.

Jacobson, E. (1925). Progressive Relaxation. The American

Journal of Psychology, 36(1):73–87. https://doi.org/

10.2307/1413507.

Kolesnichenko, O. S., Matcegora, Y. V., Prikhodko, I. I.,

and Yurieva, N. V. (2016). Methods of determining

the psychological readiness for military personnel at

risk. Honor and Law, 4(59):77–89. http://chiz.nangu.

edu.ua/article/view/137870.

Koltun, K. J., Bird, M. B., Forse, J. N., and Nindl, B. C.

(2023). Physiological biomarker monitoring during

arduous military training: Maintaining readiness and

performance. Journal of Science and Medicine in

Sport, 26(Supplement 1):S64–S70. https://doi.org/10.

1016%2Fj.jsams.2022.12.005.

Kyrychenko, A. (2020). Features of psychological readi-

ness of airborne assault servicemen troops of the

Armed Forces of Ukraine during performance of tasks

on purpose. Bulletin of National Defense University

of Ukraine, 55(2):50–58. https://doi.org/10.33099/

2617-6858-2020-55-2-50-58.

Lytvyn, A. V. and Rudenko, L. A. (2021). Formation

of psychological readiness of cadets of SES higher

schools to work in risky circumstances. Bulletin of

Alfred Nobel University. Series “Pedagogy and Psy-

chology”, (1 (21)):40–46. https://doi.org/10.32342%

2F2522-4115-2021-1-21-5.

McCrory, P., Cobley, S., and Marchant, P. (2013). The Ef-

fect of Psychological Skills Training (PST) on Self-

Regulation Behavior, Self-Efficacy, and Psycholog-

ical Skill Use in Military Pilot-Trainees. Military

Psychology, 25(2):136–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/

h0094955.

Nassif, T. H., Adrian, A. L., Gutierrez, I. A., Dixon,

A. C., Rogers, S. L., Jha, A. P., and Adler, A. B.

(2021). Optimizing Performance and Mental Skills

With Mindfulness-Based Attention Training: Two

Field Studies With Operational Units. Military

Medicine, 188(3-4):e761–e770. https://doi.org/10.

1093/milmed/usab380.

Sekel, N. M., Beckner, M. E., Conkright, W. R., LaGoy,

A. D., Proessl, F., Lovalekar, M., Martin, B. J.,

Jabloner, L. R., Beck, A. L., Eagle, S. R., Dretsch,

M., Roma, P. G., Ferrarelli, F., Germain, A., Flana-

gan, S. D., Connaboy, C., Haufler, A. J., and Nindl,

B. C. (2023). Military tactical adaptive decision mak-

ing during simulated military operational stress is in-

fluenced by personality, resilience, aerobic fitness,

and neurocognitive function. Frontiers in Psychol-

ogy, 14:1102425. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.

1102425.

Taylor, M. K., Stanfill, K. E., Padilla, G. A., Markham,

A. E., Ward, M. D., Koehler, M. M., Anglero, A.,

and Adams, B. D. (2011). Effect of Psychologi-

cal Skills Training During Military Survival School:

A Randomized, Controlled Field Study. Military

Medicine, 176(12):1362–1368. https://doi.org/10.

7205/MILMED-D-11-00149.

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

40