Applying the Content-Based Instruction Approach to Vocabulary

Acquisition for Students of English for Specific Purposes

Larysa V. Mosiyevych

1 a

, Olena M. Mikhailutsa

1 b

, Karina V. Belokon

1 c

,

Andriy V. Pozhuyev

1 d

, Tetiana V. Kurbatova

2 e

1

Zaporizhzhia National University, 66 Zhukovskoho Str., Zaporizhzhia, 69600, Ukraine

2

Kryvyi Rih National University, 27 Vitalii Matusevych Str., Kryvyi Rih, 50027, Ukraine

Keywords:

Content-Based Instruction, Grammar-Translation Method, Mechanical Engineering, Semantization, Transla-

tion, Vocabulary Acquisition.

Abstract:

The article aims to analyze the efficiency of applying the CBI (content-based instruction) approach to vocabu-

lary acquisition for Mechanical Engineering students in ESP (English for Specific Purposes) classes. Analysis

of Ukrainian coursebooks in ESP for Mechanical Engineering students shows that vocabulary acquisition is

provided via Grammar-Translation Method (GTM). The pedagogical experiment is carried out to compare

the vocabulary acquisition results based on the CBI and GTM. Group 1 and Group 2 are presented with new

terminology via the above-mentioned methods. They also do different activities for mastering new terms. At

the final stage, students do vocabulary assessment tests and questionnaire. Based on the results obtained, stu-

dents’ errors are studied. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney’s test proves the hypothesis stated. In conclusion benefits

and drawbacks of the CBI and the GTM are given. The authors develop recommendations for implementing

CBI principles in vocabulary acquisition in ESP classes. The paper is intended for a wide range of specialists

interested in teaching ESP and students.

1 INTRODUCTION

Presenting new terminology is an indispensable stage

in ESP. It is assumed that students will learn a for-

eign language faster, better, and feel more confident

in using it in the workplace if they effectively mas-

ter subject-specific/profession-related terms (Cauli,

2021). Since terms are the basis of professional

communication, neither reading nor speaking on pro-

fessional topics is possible without mastering them

(Bakirova, 2020). Learning technical terms in isola-

tion is difficult for students, thus teachers should de-

velop strategies to deal with the vocabulary they en-

counter (Quero and Coxhead, 2018).

Many ESP researchers prove that vocabulary

teaching and learning is one of the most important as-

pects of ESP alongside the development of four basic

skills. It is the underlying component on which other

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3576-9736

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2935-7997

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2000-4052

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4083-5139

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0991-2343

skills can be developed (Khazaal, 2019), “... foun-

dation upon which to build the overall language profi-

ciency” (Costeleanu, 2019). Vocabulary acquisition is

essential in ESP because it helps learners understand

the language and ideas of their field of activity (Quero

and Coxhead, 2018).

Although there are some methodological papers

deal with designing an ESP course for Mechanical

Engineering students (Elizondo Gonz

´

alez et al., 2020;

Izidi and Zitouni, 2017), there are no specific papers

about teaching terminology for Mechanical Engineer-

ing students of ESP. That is why the problem of pre-

senting new terminology for Mechanical Engineering

students in ESP lessons is quite relevant.

As noted by Chirobocea (2018) and Marinov

(2016), translation as a teaching method has been as-

sociated with the grammar-translation method for a

very long time and, consequently, its use in teaching

a foreign language is often criticized (Mart, 2013).

Benati (2018) also defines the grammar-translation

method as a traditional one which “...involves very

little spoken communication and listening compre-

hension”. The drawbacks of the grammar-translation

method are as follows:

50

Mosiyevych, L., Mikhailutsa, O., Belokon, K., Pozhuyev, A. and Kurbatova, T.

Applying the Content-Based Instruction Approach to Vocabulary Acquisition for Students of English for Specific Purposes.

DOI: 10.5220/0012646200003737

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning (ICHTML 2023), pages 50-60

ISBN: 978-989-758-579-1; ISSN: 2976-0836

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

1) the result of this approach is usually a student’s

inability to use language for communication;

2) it does not focus on the context so the communi-

cation skills of learners remain poor.

The problem of teaching ESP for Mechanical En-

gineering students also deals with a lack of relevant

coursebooks. The scope of Ukrainian coursebooks

in ESP for Mechanical Engineering students shows

that they are based on the principles of the GTM.The

new words are introduced through English-Ukrainian

translation.The set of vocabulary activities is also

based on translation. Here is a comparative analy-

sis of Ukrainian coursebooks in the context of our re-

search objective (table 1).

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Ukrainian coursebooks in

ESP for Mechanical Engineering students.

Vocabulary

learning

stages

The textbook by

Ivanov et al. (2013)

The textbook by

Shestopal and Slo-

bodyanyuk (2017)

Presenting

a new vo-

cabulary

Translation Translation

Practicing

exercises

Including English-

Ukrainian and

Ukrainian-English

translation exer-

cises

Including

Ukrainian-English

translation exer-

cises

Assessment

Test

None Multiple-choice

test in English

Thus, available Ukrainian coursebooks in ESP for

Mechanical Engineering students are mainly based on

the grammar-translation method.

The English textbook “Career Paths: Mechanics”

(Dearholt, 2015) is rated according to the Common

European Framework of Reference for Languages at

A1 (Book 1), A2 (Book 2), and B1 (Book 3) lev-

els. They are inappropriate for third-year Bachelor

students.

The e-coursebook “English for Mechanics” by

May (2005) lacks language and content activities, ex-

cept for providing answers to questions. Open Ed-

ucational Resources (OER) do not have any English

for Mechanics coursebooks available. Thus, the re-

view of resources revealed that among available ESP

coursebooks for 3rd-year mechanical engineering stu-

dents, there are either materials of inappropriate En-

glish level (among authentic coursebooks) or course-

books based on the GTM (in the Ukrainian ESP do-

main).

As an alternative, the CBI use in vocabulary ac-

quisition in ESP classes is proposed in the study. CBI

is an approach to language teaching in which content,

texts, activities, and tasks drawn from subject-matter

topics are used to provide learners with authentic lan-

guage input and engage learners in authentic language

use (Brown and Bradford, 2017).

Content-based instruction is considered as one of

the effective instructional methodologies because it

uses English as a medium to teach content knowledge

while generating multiple opportunities for students

to use English in class (Vanichvasin, 2019).

The development of vocabulary plays a crucial

role for students of content-based instruction, as vo-

cabulary development directly impacts their academic

achievements by meeting both content and language

learning objectives. CBI students need to master gen-

eral English vocabulary for communication, as well as

terms that are specific to their areas (Echevarr

´

ıa et al.,

2010).

ESP vocabulary instruction is analyzed through

comparison of CBI vs. GTM for Iranian Management

students. The results indicated a significant propriety

of CBI over the GTM in improving vocabulary acqui-

sition of the ESP students (Ahmadi-Azad and Kuhi,

2016).

The problem of searching for the best methods

is relevant in the Ukrainian educational environment.

Although CBI is not so popular in Ukraine, it is

quite relevant for ESP classes. According to the

British Council review conducted in Ukraine, ESP

and EMI are considered dominant approaches in En-

glish teaching at Ukrainian non-philological Univer-

sities (Bolitho and West, 2017). In the latest research,

CLIL is added to ESP and EMI as the three principal

approaches in tertiary education in Ukraine (Zarichna

et al., 2020). CLIL implementation in the Ukrainian

educational system has become a subject of the lat-

est research by Leshchenko et al. (2018). The CBI

approach has not received sufficient attention in ESP

teaching at Ukrainian technical universities, and its

effectiveness needs to be examined.

The article aims to compare the application of the

CBI and the GTM for vocabulary acquisition for Me-

chanical Engineering students in ESP classes.

The research aim entails solving the following

tasks:

1) examining the CBI principles;

2) designing vocabulary activities based on the GTM

and the CBI principles;

3) comparing the results of mastering new terminol-

ogy through the CBI and the GTM;

4) surveying the students from both groups regarding

to assess the methods applied at a lesson;

5) identifying benefits and drawbacks of the CBI and

the GTM in ESP classes;

Applying the Content-Based Instruction Approach to Vocabulary Acquisition for Students of English for Specific Purposes

51

6) developing recommendations for implementing

CBI principles in vocabulary acquisition in ESP

classes.

Hypothesis: based on the above-mentioned

tasks, we expect that vocabulary acquisition through

the CBI approach will outperform the grammar-

translation method.

2 METHODS

A total of 40 third year bachelor’s degree students

of Mechanical Engineering specialty of the Engineer-

ing Institute of Science and Education, Zaporizhzhia

National University are engaged in the pedagogical

experiment. They were randomly divided into two

groups, with 20 students in each group: 18 males and

2 females. The participants’ age range was from 19

to 21. All of them speak Ukrainian as their mother

tongue and learn English as a foreign language.

The grouping was not determined by their over-

all proficiency in English since the students had a

similar level, as indicated by a Comprehensive En-

glish Language Test conducted prior to the distribu-

tion. In Group 1 new terms are introduced and mas-

tered through the CBI, in Group 2 – through the GTM.

The comparison results of successful memorization

of new terminology are based on the test conducted

at the next lesson. Besides, the students from both

groups are surveyed regarding the applied method.

Thus, research results are based on quantitative data

from test results and qualitative data collected from

students’ questionnaires.

The research is carried out in three stages. At the

first stage, a mechanical engineering-related text with

new terms is selected. New terms are introduced to

twenty students in Group 1 via visual aids and via

the translation method in Group 2 before reading the

same text. After that, the students in both groups read

the text and do the vocabulary activities which are dif-

ferent in both groups.

At the second stage, the vocabulary assessment

test enables to compare the results of vocabulary ac-

quisition in both groups. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney’s

test is applied for proving the hypothesis stated. The

additional data required are collected from question-

naires to get the students‘ responses to the CBI/the

GTM in vocabulary acquisition.

At the third stage, the item difficulty of test results

is calculated in each group, and compared.

To sum up, the experimental data are obtained

from the results of vocabulary assessment test, and

students’ questionnaires.

3 RESULTS

The results are based on qualitative and quantitative

data collection. Qualitative data are collected from

the students’ questionnaires. Information about their

attitude toward a method applied at the lesson is col-

lected. Four evaluation criteria are included: vo-

cabulary presentation, meaningful activities, cogni-

tive load, engagement/interest.

Comparison of the effectiveness of specified

teaching methods in the two groups for a significance

level of 5% for each criterion is conducted using the

Mann-Whitney U-test. Hypotheses are formulated for

each evaluation criterion: H

0

– the results in the two

groups do not differ significantly, and H

1

– the results

in the two groups differ significantly. The calculated

data are presented in table 2.

Table 2: Students’ questionnaires about the GTM and the

CBI approaches.

Evaluation criteria

CBI

average

score

GTM

average

score

U

emp

1. Vocabulary presentation

(scale 1-5)

4.5 3.75 75

2. Meaningful activities

(scale 1-5)

4.5 4.25 156.5

3. Cognitive load (high /

medium / low)

medium high

4. Engagement/ interest

(scale 1-5)

5 3.75 15

For the given level of significance α = 0.05, and

sample sizes n

1

= 20, n

2

= 20, we find the critical

value as U

crit

= 127 from the table. The comparison

of the obtained empirical values for each evaluation

criterion with the critical value enables the following

conclusion: the majority of students from Group 1

have more positive attitude toward using visual aids

and contextualization. The students from Group 2

have negative attitude toward vocabulary presentation

through translation and out of context. The results

in Criterion 2 are quite similar: the students from

both groups find the vocabulary activities meaning-

ful. The majority of students in Group 2 indicate high

cognitive load in the GTM, while Group 1 indicates

its medium level. While all the students in Group 1

find the CBI approach engaging and interesting based

on the final criterion, in Group 2, students have ex-

pressed an opposite opinion toward the GTM. The re-

sults enable to conclude that students in Group 1 have

a more positive attitude toward the CBI, while stu-

dents in Group 2 exhibit a less positive attitude toward

the GTM.

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

52

Quantitative data are based on the results of the

same multiple-choice test for both groups. The to-

tal number of questions is 30. They are supposed to

be distributed among the first three levels of Bloom’s

taxonomy: remembering (items 1-10), understanding

(items 11-20), and applying (items 21-30).

The number of mistakes made in the test at each

cognitive level enables calculating an item difficulty.

We calculated it for both groups, as shown in table 3

and table 4.

The formula used to calculate the item difficulty is

presented in formula (Maharani and Putro, 2020):

item

di f f iculty

=

N

correct

N

tested

(1)

where: N

correct

– the number of students who an-

swered correctly; N

tested

– the number of students who

are tested.

Table 3: Item difficulty in Group 1.

Cognitive

level

Number

of

items

in a test

Number

of stu-

dents who

answered

a question

correctly

Number

of stu-

dents in

Group 1

The

diffi-

culty

index

Remembering 10 15 0.75

Understanding 10 15 20 0.75

Applying 10 13 0.65

Table 4: Item difficulty in Group 2.

Cognitive

level

Number

of

items

in a test

Number

of stu-

dents who

answered

a question

correctly

Number

of stu-

dents in

Group 2

The

diffi-

culty

index

Remembering 10 13 0.65

Understanding 10 11 20 0.55

Applying 10 8 0.4

The next step is to compare item difficulty in both

groups (table 5).

Table 5: Comparison of item difficulty in both groups.

Cognitive level

Item difficulty

in Group 1 in Group 2 difference

Remembering 0.75 0.65 0.1

Understanding 0.75 0.55 0.2

Applying 0.65 0.4 0.25

According to the results, no significant difference

is found in the questions at the remembering level

between Groups 1 and 2 (0.1). However, more sig-

nificant differences are observed in the questions at

the understanding comprehension and applying ap-

plication levels (0.2 and 0.25, respectively). As the

cognitive complexity of tasks increases according to

Bloom’s taxonomy, students in Group 2 exhibit a

higher frequency of errors.

The result supports the hypothesis that the stu-

dents taught through the CBI method demonstrate su-

perior vocabulary acquisition compared to the group

instructed by the GTM. This can be attributed to the

fact that the activities based on the CBI approach are

more meaningful, engaging, and motivating. Addi-

tionally, visualization and contextualization prove to

be beneficial.

4 DISCUSSION

CBI and GTM differ in methodological backgrounds,

so they are expected to result in different outcomes in

vocabulary acquisition in ESP teaching. The vocabu-

lary acquisition is divided into three stages (table 6).

Table 6: Stages of the vocabulary acquisition.

Stages Group 1 Group 2

Presenting

new terms

Visual aids Translation

Practicing ex-

ercises

L2 (target lan-

guage) exercises

L1-L2/L2-L1

exercises

Vocabulary as-

sessment test

Multiple-choice est

in L2

Multiple-choice

test in L2

4.1 Presentation of new terms

To approbate the CBI approach, the theme “Suspen-

sion system” is chosen. The text for reading is taken

from an electronic coursebook “English for Mechan-

ics” by May (2005). It should be noted that the theme

is rather essential for learning, however, it is included

in none of the above-mentioned Ukrainian course-

books in ESP for Mechanical Engineering students.

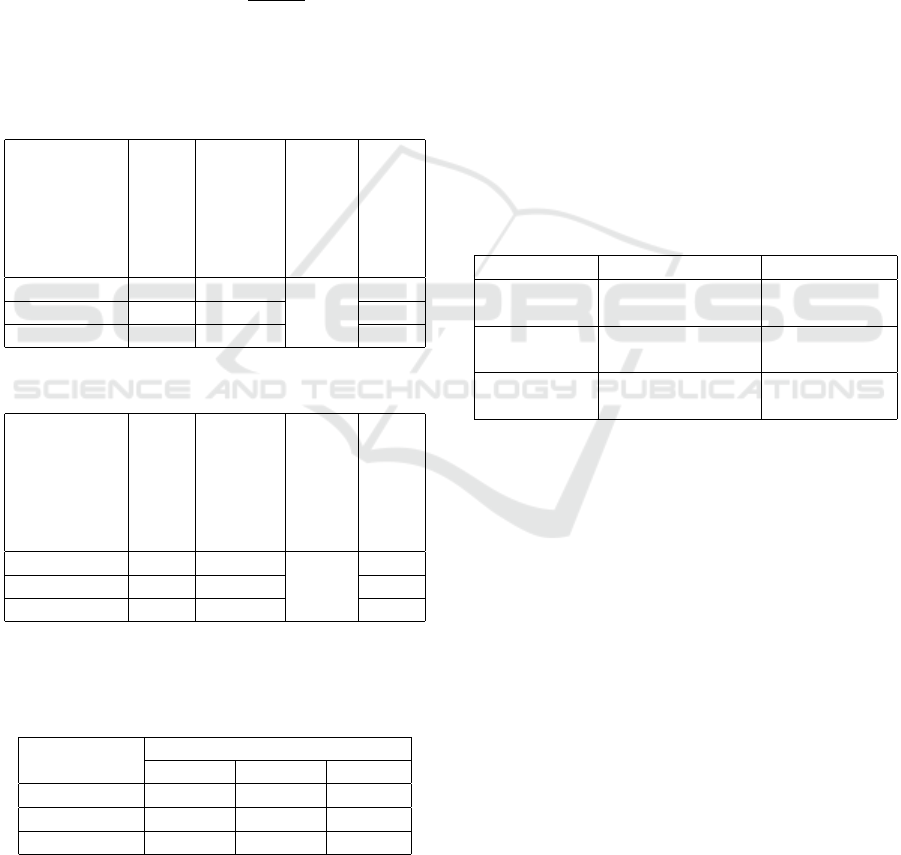

To initiate the lesson, a word cloud is employed as a

lead-in. The word cloud, generated using a digital tool

called Word Art, is based on the text “Suspension Sys-

tem”. It serves to introduce students to a new topic,

activate their prior knowledge about the subject, and

functions as an introductory stage of the lesson (fig-

ure 1).

ESP teachers might consider the following steps in

their procedures for vocabulary instruction (Tumolo,

2007):

1) a source of new words presentation;

Applying the Content-Based Instruction Approach to Vocabulary Acquisition for Students of English for Specific Purposes

53

Figure 1: Word cloud.

2) activities done for understanding the meaning of

the words;

3) creation of memory links and retention of the

word form and meaning.

The following techniques can be used in the se-

mantization process (Jata, 2018):

1) visualization;

2) definitions and explanation;

3) matching;

4) synonyms or antonyms;

5) guessing from the context.

A visual technique for semantization of Mechan-

ical Engineering terms has been chosen for our re-

search since visualization is one of the most efficient

memorization strategies. Besides, verbal techniques

are useful to explain more abstract concepts. Visual-

ization is the way that can enable students to guess

the meaning of unknown words and comprehend a

text (Ghaedi and Shahrokhi, 2016). Visual learners

can create mental images related to target words that

help them memorize and store them in their long-term

memory (Mohd Tahir and Tunku Mohtar, 2016). It

should be noted that the visual method is rather rele-

vant for students because a suspension system in L1

is familiar to them.

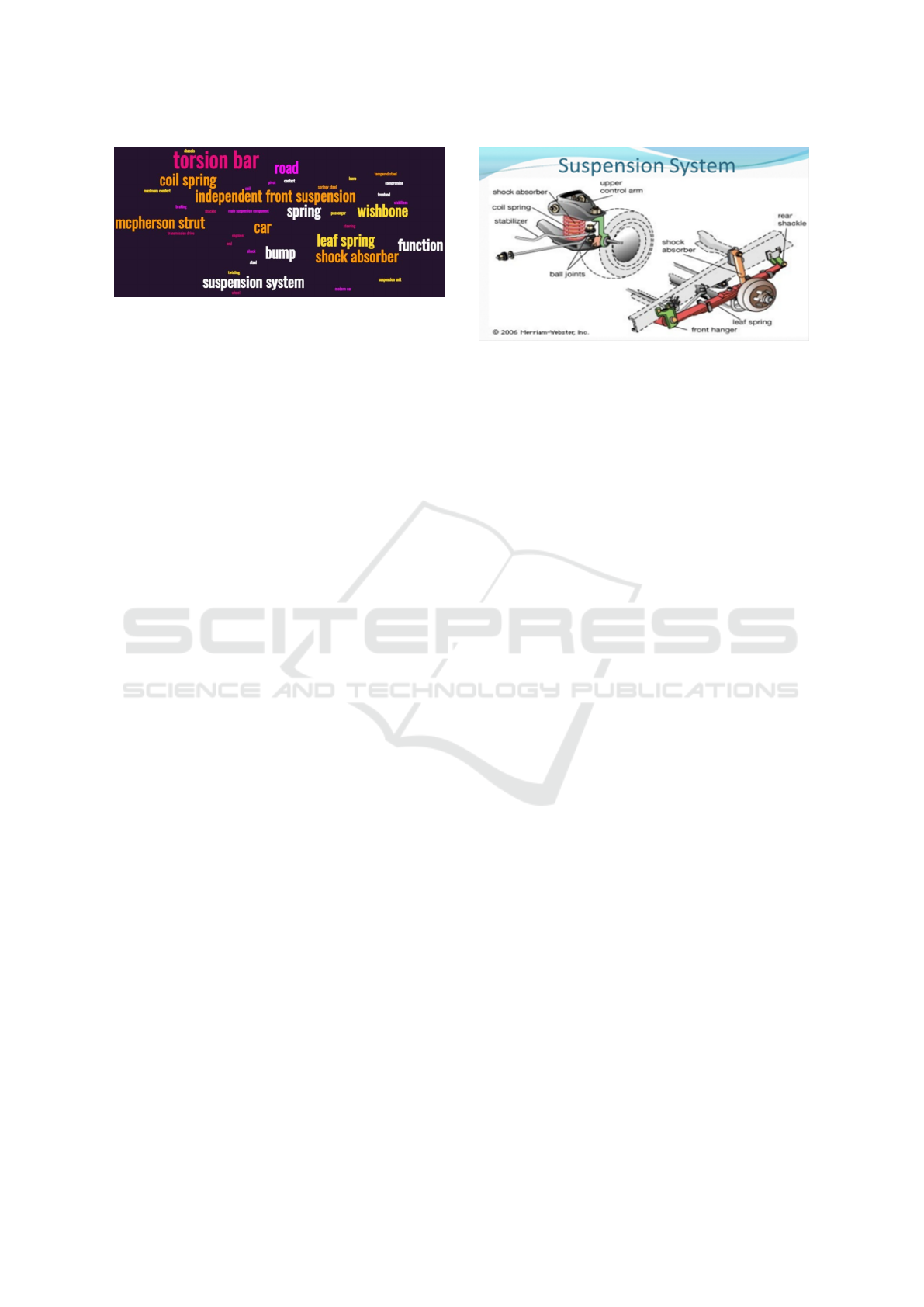

In Group 1, new terms are presented by visual aids

before reading the text. The key terms are Shock ab-

sorber, Upper control arm, Coil spring, leaf spring,

Stabilizer, Ball joints, Front hanger, and Rear shackle.

The students should find these words in the image and

guess their meaning (figure 2).

In Group 2, new terms are introduced by provid-

ing translations into Ukrainian, following the princi-

ples of the GTM. After the new terms are introduced,

students from both groups read the text “The suspen-

sion system”:

The suspension system of a car has two main func-

tions. Firstly, it must keep all four road wheels in con-

tact with the road, so that steering, braking, and the

transmission drive can operate properly. Secondly,

Figure 2: Suspension system.

the suspension system must offer passengers maxi-

mum comfort. The two functions are never quite com-

patible, so engineers always make a compromise. The

main suspension components in modern cars are leaf

springs, coil springs, wishbones, torsion bars, shock

absorbers, and McPherson struts. Leaf springs are

leaves of tempered steel clamped together and fas-

tened to the chassis by a shackle at one end, a pivot

at the other. Coil springs are often used together with

wishbones to give an independent front suspension.

McPherson struts also offer independent front sus-

pension. They use a coil spring together with a shock

absorber. The spring absorbs bumps, while the shock

absorber dampens (stabilizes) up and down bouncing.

A torsion bar is springy steel that absorbs bumps by

twisting and untwisting. Torsion bars are often part

of the front-end suspension unit.

4.2 Practicing new terms

The acquisition of new terms takes place within a sin-

gle lesson lasting 85 minutes.

4.2.1 Practicing new terms in Group 1

We provide vocabulary acquisition for Group 1 based

on CBI principles:

1) students’ prior knowledge can help or hinder

learning. When students can connect new infor-

mation with knowledge and beliefs that they had

previously, they will remember more and learn

more quickly;

2) the more interrelationships among concepts, and

the stronger and clearer those relationships, then

the better a learner’s understanding and ability to

apply the concepts to new problems and new situ-

ations;

3) students’ motivation determines, and directs;

4) to combine content and language lesson objec-

tives in one class period;

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

54

5) scaffolding: when teachers create supportive con-

ditions in which the student can participate and

extend their current skills and knowledge to reach

higher levels of competence;

6) no L1 (native language) in classes.

The principal types of post-reading activities for

mastering new terms are as follows:

1. Matching exercises

2. Gap-filling exercises

3. True/false exercises

4. Categorization of words

5. Multiple-choice exercises

6. Answering questions

We agree with Myshak (2018) that the efficiency

of assimilation of terms and their active use in oral

and written professional speech depend in many re-

spects on the appropriate system of exercises consis-

tently aimed at both thorough understanding of ter-

minology and enhancement of speaking and listening

skills necessary for the application of this terminol-

ogy to specific situations.

According to the CBI principles, students need to

encounter new vocabulary in a variety of meaningful

settings and activities. The activities divised by the

authors offer opportunities for the students in Group 1

to learn and practice the newly introduced vocabulary

words:

Task 1. Match the terms (1-7) with their defini-

tions (A-G):

1. Suspension

2. Wishbones

3. Spring

4. Strut

5. Shackle

6. Torsion

7. Steering

A) the collection of components, linkages, etc. which

allows any vehicle (car, motorcycle, bicycle) to

follow the desired course;

B) the twisting of an object due to an applied torque;

C) a U-shaped piece of metal secured with a clevis

pin or bolt across the opening;

D) system of components allowing a machine (nor-

mally a vehicle) to move smoothly with reduced

shock;

E) Devices that are used to control the front wheels

of automobiles;

F) an elastic object that stores mechanical energy;

G) components of an automobile chassis, can be pas-

sive braces to reinforce the chassis and/or body, or

active components of the suspension.

Task 2. Fill in the gaps:

1) The main suspension components in modern cars

are. . . .

2) The suspension system must offer passengers. . .

3) A torsion bar is springy steel that absorbs bumps

by. . . .

4) The . . . stabilizes up and down bouncing.

Task 3. Tick the false statements:

1) The suspension system of a car has four main

functions.

2) Steering, braking, and the transmission drive must

operate properly.

3) The main suspension components in modern cars

are leaf springs and coil springs.

4) Coil springs are leaves of tempered steel clamped

together and fastened to the chassis by a shackle

at one end, a pivot at the other.

Task 4. Match a part of the suspension system (1-

4) with its function (a-d) and read the sentences:

1. Suspension system

2. Coil springs

3. Ball joints

4. Shock absorbers

a) To support the coil spring to further reduce the

impact of a bump or pothole;

b) To connect your steering knuckles to the control

arms;

c) To maximize the friction between your car’s tires

and the road;

d) To absorb the impact when a vehicle hits a bump

in the road.

A stem sentence can be given as a model: ”The

function of the ... is to ...”

Task 5. Answer the questions:

1) What are the functions of the suspension system

of a car?

2) What are the main suspension components?

3) Is a torsion bar used for speeding?

4) Are torsion bars and shock absorbers often used

together to give independent front suspension?

Applying the Content-Based Instruction Approach to Vocabulary Acquisition for Students of English for Specific Purposes

55

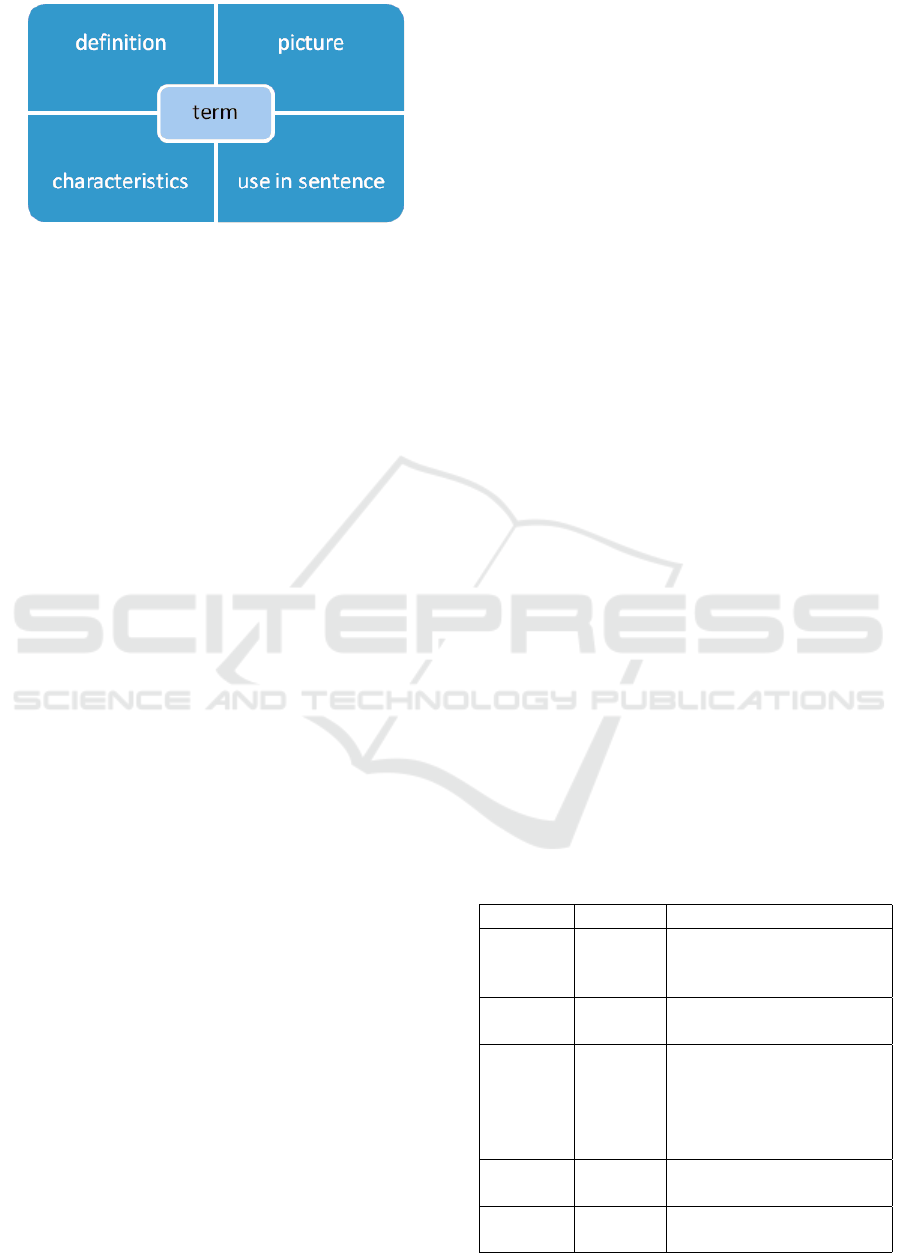

Figure 3: Frayer model.

The students are expected to study the new terms

outside the class, where they should create the Frayer

model (figure 3).

The Frayer model is an effective way to help the

students understand the meaning of new words, use

them correctly in sentences, and construct derivatives.

As an out-of-class activity, the students are also

asked to create a mind map illustrating the compo-

nents and functions of a suspension system. The dig-

ital tools such as Mind Meister, Canva, Wise map-

ping can be applied. Mind maps facilitate students’

engagement, and help them recall and solidify new

terms. Additionally, students are expected to review

the new terms using flashcards on the Quizzlet plat-

form.

Thus, the given set of vocabulary activities pro-

vides students with numerous exposures to new vo-

cabulary in meaningful and contextualized ways. The

activities create memory links and enhance retention

of a word form and its meaning.

4.2.2 Practicing new terms in Group 2

Following the principles of the grammar-translation

method (Milawati, 2019), and imitating a set of ac-

tivities in above-mentioned GMT-related Ukrainian

coursebooks, we designed the following vocabulary

activities for Group 2:

Task 1. Read and translate the text “The suspen-

sion system” (see 3.1).

Task 2. Answer the questions:

1) What are the functions of the suspension system

of a car?

2) What are the main suspension components?

3) Is a torsion bar used for speeding?

4) Are torsion bars and shock absorbers often used

together to give independent front suspension?

Task 3. Match the terms (1-7) with their defini-

tions (A-G):

1. Suspension

2. Wishbones

3. Spring

4. Strut

5. Shackle

6. Torsion

7. Steering

A. the collection of components, linkages, etc. which

allows any vehicle (car, motorcycle, bicycle) to

follow the desired course;

B. the twisting of an object due to an applied torque;

C. a U-shaped piece of metal secured with a clevis

pin or bolt across the opening;

D. system of components allowing a machine (nor-

mally a vehicle) to move smoothly with reduced

shock;

E. Devices that are used to control the front wheels

of automobiles;

F. an elastic object that stores mechanical energy;

G. components of an automobile chassis can be pas-

sive braces to reinforce the chassis and/or body, or

active components of the suspension.

Task 4. Find the examples of Passive Voice in the

text.

Task 5. Translate the sentences from English into

Ukrainian.

Task 6. Translate a text from Ukrainian into En-

glish.

The final activity is rather time-consuming to be

assigned as an in-class task. However, it would not

be reasonable to propose it as an out-of-class task, as

students might apply machine translation.

A table summarizing the information about activi-

ties in both groups enables to compare them (table 7).

Table 7: Comparison of vocabulary activities in both

groups.

Criteria Group 1 Group 2

Using the

mother

tongue

- +

Cognitive

load

Not high High due to translation

skills

Relevant /

irrelevant

Relevant Activities involving transla-

tion are irrelevant: they are

time-consuming, and stu-

dents can translate them us-

ing ChatGPT/MT

Vocabulary

exposure

Much high Little low

Using digi-

tal tools

+ -

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

56

Thus, translation activities not only focus on key

content vocabulary but also on passive vocabulary and

grammar structures, leading to the split-attention ef-

fect and high cognitive load.

4.3 Vocabulary assessment tasks and

questionnaire

The vocabulary assessment multiple-choice test is

conducted at the next lesson in both groups. The to-

tal number of questions is 30. They are supposed to

be distributed at the first three levels, remembering

(items 1-10), understanding (items 11-20), and apply-

ing (items 21-30), of Bloom’s taxonomy.

These three cognitive levels are relevant for new

vocabulary acquisition. The number of mistakes

made in the test on this or that cognitive level enables

calculating an item difficulty. The formula looks like

this: the number of students who answer a question

correctly (c) is divided by the total number of students

in the group who answered the question (s). The an-

swer equals a value between 0.0 and 1.0, with harder

questions resulting in values closer to 0.0 and easier

questions resulting in values closer to 1.0. The for-

mula is: c ÷ s = p (Renner, 2018). We calculate the

item difficulty for both groups separately (table 3 and

table 4).

The cognitive levels are not marked in the test, and

the students can not see them. One sample question

for each level is provided:

Level of remembering:

What is the term for the part of the suspension sys-

tem that connects the wheel to the vehicle’s body?

a) Shock absorber

b) Control arm

c) Sway bar

d) Strut

Level of understanding:

How does the suspension system contribute to ve-

hicle stability during cornering?

a) By reducing vibrations and shocks

b) By maintaining optimal tire contact with the road

c) By adjusting the ride height automatically

d) By controlling the engine’s power output

Level of applying:

You want to enhance the off-road capabilities of

your vehicle. Which suspension component should

you consider upgrading?

a) Shock absorbers

b) Coil springs

c) Control arms

d) Sway bars

Qualitative data are collected from the students’

questionnaires (table 2). Information about their at-

titude towards the method applied in the lesson was

collected. Four evaluation criteria are included: vo-

cabulary presentation, meaningful activities, cogni-

tive load, and engagement/interest.

5 ANALYSIS OF DATA OBTAINED

The pedagogical experiment is conducted to compare

the CBI approach and the GTM at the vocabulary ac-

quisition stage in ESP classes. Methods of mathemat-

ical statistics are applied to data processing.

As a null hypothesis H

0

, it is assumed that there

is no significant difference between students who are

taught using the grammar-translation method (GTM)

and students who are taught using the CBI approach

to enhance students’ vocabulary acquisition. Alter-

native hypothesis H

1

, implies that there is a signifi-

cant difference between students who are taught us-

ing the GTM and those who are taught using the CBI

approach to enhance their vocabulary acquisition.

To prove or reject the hypotheses stated, the

results in the experimental and control groups are

compared before and after the experiment applying

the CBI principles by using the Wilcoxon-Mann-

Whitney’s test. The Mann-Whitney U test is used to

compare differences between two independent sam-

ples when the sample distribution is not normal and

the sample sizes are small n < 30). When analyzing

the results of the experiment, the use of this criterion

is advisable, since for the obtained samples the re-

quirement of a normal distribution for the t-criterion

is not met, and this was confirmed by constructing fre-

quency histograms for both groups. Based on the test

results, tables are compiled for calculating the rank

sums for students’ samples in both groups. The SPSS

Statistics software is used to calculate the criterion.

The empirical value of the criterion U is calculated

by the formula:

U = n

1

· n

2

+

n

x

(n

x

+ 1)

2

− T

x

where:

n

1

is the number of students in the experimental

group;

n

2

is the number of students in the control group;

n

x

is the number of students in the group with a

higher rank sum;

T

x

is the larger of the two rank sums.

Applying the Content-Based Instruction Approach to Vocabulary Acquisition for Students of English for Specific Purposes

57

The empirical value of the Wilcoxon criterion is

determined from the ratio:

W

exp

=

|

n

1

·n

2

2

−U|

q

n

1

·n

2

·(n

1

+n

2

+1)

12

The critical value is determined according to the

corresponding table at the significance level of 5%.

The empirical value of the vocabulary acquisition

criterion at the beginning of the control stage of the

experiment is in the insignificance zone, that is, there

is no significant difference in the knowledge level

among the students of the experimental and control

groups. The empirical value of the Mann-Whitney

U-criterion at the end of the control stage of the ex-

periment W

emp

= 2.29 is compared with the critical

value W

0.05

= 1.96. Since W

emp

> 1.96, we can con-

clude that the reliability of the differences in the char-

acteristics of the compared samples is 95%. It en-

ables rejecting hypothesis H

0

about the CBI princi-

ples proposed in the study at the stage of terminolog-

ical vocabulary acquisition. However, the alternative

hypothesis about the impact of that approach on the

level of terminological vocabulary acquisition among

future mechanical engineers is accepted.

6 CONCLUSIONS

A comparative analysis of the CBI and the GTM for

ESP lessons is conducted. The results are obtained

on the basis of the students’ questionnaires, and a

multiple-choice vocabulary test.

The data obtained demonstrate the superiority

of the CBI approach over the traditional GTM in

terms of effective vocabulary acquisition for Me-

chanical Engineering students in ESP. Throughout

the conducted investigation, the objectives have been

achieved. We can conclude that vocabulary learning

involves a certain amount of memorization. Learning

words in context (as facilitated by the CBI approach)

is regarded as more effective. Teaching students how

to practice circumlocution rather than going straight

to translation is giving them a valuable skill. It also

gives them more practice with L2. Students encounter

new vocabulary in a variety of meaningful settings

and activities. CBI activities can provide repetition

and exposure that is indispensable for vocabulary ac-

quisition.

The research results enable to sum up the advan-

tages and disadvantages of both methods (table 8).

The questionnaire responses of students in Group

1 showed that they enjoyed doing vocabulary activi-

ties and did not find it difficult to do the final vocab-

ulary assessment test. Motivation and interest con-

Table 8: Benefits and drawbacks of the CBI and the GTM.

The CBI The GTM

Using no mother tongue Using the mother tongue

Appropriate for bilingual

groups

Inappropriate for bilin-

gual groups

Introducing new vocabu-

lary in context, and en-

gaging manner

Introducing new vocab-

ulary using the mother

tongue

Developing a profession

oriented lexical compe-

tence

Developing translation

competence is irrelevant

for STEM students

Stimulating, rewarding Boring

More challenging for a

teacher

More challenging for a

student

tribute to positive outcomes in learning. On the con-

trary, students in Group 2 reveal a negative attitude

towards the vocabulary activities. Thus, CBI princi-

ples are eligible to be applied in ESP classes.

Analysis of data obtained enables us to develop

recommendations for implementing CBI principles in

vocabulary acquisition in ESP classes:

1) supply meaningful topics and texts;

2) categorize new words into technical terms and

general English words;

3) introduce vocabulary via visual aids;

4) take students’ cognitive load into account;

5) use motivating and stimulating vocabulary activi-

ties with digital tools (word clouds, Frayer mod-

els, infographics, mind maps, etc.).

Further research prospects involve analysis of ap-

plying CBI to mastering listening and speaking skills

for Mechanical Engineering students in ESP classes.

REFERENCES

Ahmadi-Azad, S. and Kuhi, D. (2016). ESP Vocabulary In-

struction: A Comparison of CBI vs. GTM for Iranian

Management students. Asean Journal of Teaching and

Learning in Higher Education (AJTLHE), 8(2):35–50.

https://ejournal.ukm.my/ajtlhe/article/view/18853.

Bakirova, H. B. (2020). Formation of terminological com-

petence in ESP education. JournalNX- A Multidisci-

plinary Peer Reviewed Journal, 6(11):63–68. https:

//tinyurl.com/mswvhzmj.

Benati, A. (2018). Grammar-Translation Method. In The

TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching,

pages 1–5. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/

10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0153.

Bolitho, R. and West, R. (2017). The interna-

tionalisation of Ukrainian universities: the

English language dimension. Stal, Kyiv.

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

58

https://www.britishcouncil.org.ua/sites/default/

files/2017-10-04 ukraine - report h5 en.pdf.

Brown, H. and Bradford, A. (2017). EMI, CLIL,

& CBI: Differing approaches and goals. In

Clements, P., Krause, A., and Brown, H., edi-

tors, Transformation in language education. JALT,

Tokyo. https://jalt-publications.org/files/pdf-article/

jalt2016-pcp-042.pdf.

Cauli, E. (2021). Implementing CLIL approach to

teaching ESP in academic contexts in Alba-

nia. Journal for Research Scholars and Profes-

sionals of English Language Teaching, 5(25).

https://www.jrspelt.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/

05/Eda-CLIL-Approach.pdf.

Chirobocea, O. (2018). A case for the use of translation

in ESP classes. Journal of Languages for Specific

Purposes, (5):67–76. https://www.researchgate.net/

publication/323858764.

Costeleanu, M. (2019). The Role Of Vocabulary In Esp

Teaching. In Soare, E. and Langa, C., editors, Edu-

cation Facing Contemporary World Issues, volume 67

of European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural

Sciences, pages 996–1002. Future Academy. https:

//doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.03.120.

Dearholt, J. (2015). Career Paths: Mechanics. Express

Publishing, London.

Echevarr

´

ıa, J., Vogt, M., and Short, D. J. (2010). Mak-

ing Content Comprehensible for Multilingual Learn-

ers: The SIOP Model. Allyn & Bakon. https://tinyurl.

com/5n999k9u.

Elizondo Gonz

´

alez, J. F., Pilgrim, Y., and S

´

anchez V

´

ıquez,

A. (2020). Dise

˜

no de un curso esp para estudiantes

de ingenier

´

ıa mec

´

anica. InterSedes, 21(43):78–102.

https://doi.org/10.15517/isucr.v21i43.41979.

Ghaedi, R. and Shahrokhi, M. (2016). The impact of vi-

sualization and verbalization techniques on vocabu-

lary learning of Iranian high school EFL learners:

A gender perspective. Ampersand, 3:32–42. https:

//doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2016.03.001.

Ivanov, O., Beshta, O., and Dolhov, O. (2013).

Anhliyska mova dlya studentiv elektromekhanichnykh

spetsialnostey [English for Mechanical Engineer-

ing Students]. Natsionalnyy hirnychyy universytet,

Dnipropetrovsk.

Izidi, R. and Zitouni, M. (2017). Esp Needs Analysis: the

Case of Mechanical Engineering Students at the Uni-

versity of Sciences and Technology Oran U.S.T.O. Re-

vue des

´

etudes humaines et sociales -B/ Litt

´

erature

et Philosophie, (18):16–25. https://doi.org/10.33858/

0500-000-018-054.

Jata, E. (2018). Teaching ESP Terminology- Case Study

Agricultural University of Tirana (AUT). Euro-

pean Journal of Language and Literature, 4(3):22–27.

https://doi.org/10.26417/ejls.v4i4.p22-27.

Khazaal, E. N. (2019). Investigating and Analyzing ESP

College Students’ Errors in Using Synonyms. Interna-

tional Journal of English Linguistics, 9(5):328–339.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v9n5p328.

Leshchenko, M., Lavrysh, Y., and Halatsyn, K. (2018). The

role of content and language integrated learning at

Ukrainian and Polish educational systems: Challenges

and implication. Advanced Education, 5:17–25. https:

//doi.org/10.20535/2410-8286.133409.

Maharani, A. V. and Putro, N. H. P. S. (2020). Item Analysis

of English Final Semester Test. Indonesian Journal of

EFL and Linguistics, 5(2):491–504. https://doi.org/

10.21462/ijefl.v5i2.302.

Marinov, S. (2016). Translation Exercise Aided by

Data-driven Learning in ESP Context. ESP To-

day, 4(2):225–250. https://doi.org/10.18485/esptoday.

2016.4.2.5.

Mart, C. T. (2013). The Grammar-translation Method and

the Use of Translation to Facilitate Learning in ESL

Classes. Journal of Advances in English Language

Teaching, 1(4):103–105. https://european-science.

com/jaelt/article/view/281.

May, T. (2005). English for Mechanics. Lulu.com.

Milawati (2019). Grammar Translation Method: Cur-

rent Practice In EFL Context. Indonesian Journal

of English Language Teaching and Applied Linguis-

tics, 1(4):187–196. https://doi.org/10.21093/ijeltal.

v4i1.437.

Mohd Tahir, M. H. and Tunku Mohtar, T. M. (2016). The

effectiveness of using vocabulary exercises to teach

vocabulary to ESL/EFL learners. Pertanika Journal

of Social Sciences & Humanities, 24(4):1651–1669.

http://www.pertanika.upm.edu.my/resources/files/

Pertanika%20PAPERS/JSSH%20Vol.%2024%20(4)

%20Dec.%202016/23%20JSSH-1459-2015.pdf.

Myshak, E. (2018). Forming terminological com-

petence of future specialists of the agroin-

dustrial and environmental branches by for-

eign language means. Euromentor Jour-

nal, 9(3):68–76. https://www.proquest.com/

openview/efe56e75eddf819a36d827997be06552/

1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1316370.

Quero, B. and Coxhead, A. (2018). Using a Corpus-Based

Approach to Select Medical Vocabulary for an ESP

Course: The Case for High-Frequency Vocabulary.

In Kırkg

¨

oz, Y. and Dikilitas¸, K., editors, Key Issues

in English for Specific Purposes in Higher Educa-

tion, pages 51–75. Springer International Publishing,

Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70214-8 4.

Renner, R. (2018). How to Calculate Diffi-

culty Index. https://www.theclassroom.com/

test-standardized-6680561.html.

Shestopal, O. and Slobodyanyuk, A. (2017). Anhliyska

mova dlya inzheneriv-mekhanikiv [English for me-

chanical engineers]. VNTU, Vinnytsya.

Tumolo, C. H. S. (2007). Vocabulary and reading: teaching

procedures in the ESP classroom. Linguagem & En-

sino, 10(2):477–502. https://www.researchgate.net/

publication/255593986.

Vanichvasin, P. (2019). Effects of Content-Based Instruc-

tion on English Language Performance of Thai Under-

graduate Students in a Non-English Program. English

Language Teaching, 12(8):20–29. https://doi.org/10.

5539/elt.v12n8p20.

Zarichna, O., Buchatska, S., Melnyk, L., and Savchuk,

T. (2020). Content and Language Integrated Learn-

Applying the Content-Based Instruction Approach to Vocabulary Acquisition for Students of English for Specific Purposes

59

ing in Tertiary Education: Perspectives on Terms of

Use and Integration. East European Journal of Psy-

cholinguistics, 7(1). https://eejpl.vnu.edu.ua/index.

php/eejpl/article/view/295.

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

60