Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions on Implementing the

Trauma-Informed Approach in Educational Institutions

Tetiana Holovatenko

1 a

1

Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University, 18/2 Bulvarno-Kudriavska Str., Kyiv, 04053, Ukraine

Keywords:

Attitudes, Competence, Knowledge, Trauma Response, Teacher Training.

Abstract:

This study examines pre-service teachers’ perceptions of their knowledge and competence in implementing

trauma-informed approach. The study has a quantitative design and is set in Ukraine. Participants (N=54)

are pre-service teachers affiliated with early childhood or primary education institutions during their practical

training. The study is set amidst a full-scale war in Ukraine. Based on the descriptional statistics, the author

concludes participants perceive their knowledge about trauma as average or below average. However, they

express relatively higher confidence in their competence to implement trauma-informed practices. The study

demonstrates the importance of the extensive introduction of a trauma-informed approach in teacher training

and formal preparation of pre-service teachers to implement trauma-informed practices. The author outlines

the suggested content plan for teaching The study adds to the field of pre-service teacher training and scholarly

research on trauma-informed practices.

1 INTRODUCTION

The full-scale invasion of Russia in sovereign Ukraine

in 2022 has impacted the education landscape not

only in Ukraine but abroad as well. It has dis-

rupted education for two-thirds of Ukrainian children

who are not currently enrolled in the Ukrainian na-

tional education system (UNI, 2024). Moreover, as

of July 2023, 6,302,600 refugees from Ukraine were

recorded globally (Operational Data Portal, 2024).

According to Ukrainian data provided by the Min-

istry of Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied

Territories of Ukraine, as of January 2023, there are

4,867,106 internally displaced people officially regis-

tered in Ukraine (Ukrinform, 2023).

Preparing pre-service teachers to respond to chal-

lenges currently imposed on the education system

should become one of the top priorities of all teacher

training institutions. Some of the challenges of teach-

ing students in wartime include continuous blackouts,

lack of Internet access, and as a result – inconsistent

knowledge of students. Moreover, a study in Kyiv

schools has shown that Ukrainian school students are

looking for emotional support from adults and having

sessions with psychologists (Khoruzha et al., 2023).

According to the study on psychosocial stress and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7545-3253

emotional health among school children in Donetsk

and Luhansk oblasts, 31% of 9 to 11-year-olds have

a high level of post-traumatic stress. This is com-

pared to 24% of 12-14-year-olds and 15-17-year-olds

(NUK, 2023). This data illustrates that young learners

are particularly vulnerable to stress and are affected

by military actions.

This statistic is not unique to Ukraine but is a ris-

ing issue across the world. For instance, according to

SAMHSA, more than two-thirds of children reported

at least 1 traumatic event by age 16 (SAMHSA,

2023). Among traumatic events mentioned by the or-

ganization, there are psychological, physical, or sex-

ual abuse; community or school violence; witnessing

or experiencing domestic violence; national disasters

or terrorism; commercial sexual exploitation; sudden

or violent loss of a loved one; refugee or war experi-

ences; military family-related stressors (e.g., deploy-

ment, parental loss or injury); physical or sexual as-

sault; neglect; serious accidents or life-threatening ill-

ness (SAMHSA, 2023).

All these traumatic events are not a challenge for

various countries and as a result, it is important for

educators to be able to respond to the challenges stu-

dents experience related to their previous experiences.

In the next section the author analyzes the theo-

retical underpinnings of the research on pre-service

teachers’ perceptions on implementing the trauma-

130

Holovatenko, T.

Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions on Implementing the Trauma-Informed Approach in Educational Institutions.

DOI: 10.5220/0012648000003737

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning (ICHTML 2023), pages 130-137

ISBN: 978-989-758-579-1; ISSN: 2976-0836

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

informed approach in educational institutions.

2 THEORETICAL GROUNDING

2.1 A Trauma-informed Approach to

Education

In this section, the author analyses various schol-

arly approaches to defining the scope of the trauma-

informed approach.

Recently teacher practitioners indicated a growing

number of students with signs of trauma, such as be-

havioural issues, academic challenges, stress and anx-

iety, and mental health issues. To address this issue, a

lot of teachers implement trauma-informed practices.

The core of trauma-informed practices is the idea

that every individual has experienced some kind of

trauma in their life, but the impact of the trauma dif-

fers from case to case (Berardi and Morton, 2019).

The aftermath of coping with trauma is a complex of

factors, such as what the stressful event was, access to

internal and external resources, and reinforcing inner

neural networks to cope with stress.

According to Forbes et al. (2020), the trauma-

informed model can be described as an opposition of

the “regulated” and “dysregulated” state of students.

The author of this paper thinks that a Regulatory

approach to responding to traumatic events creates a

welcoming space for all students as they are, no mat-

ter what behaviour they demonstrate. Hence, it is one

of the reasons why all classrooms and schools should

become trauma-informed.

An overarching idea is expressed by Venet (2021),

who states that focusing on the individual needs of

students, does not respond to the community needs

and leads to continuous problems within a school.

Venet (2021) suggests adopting the Universal ap-

proach regardless of the number of students who are

traumatized.

Both Universal and Regulatory approaches have

one thing in common – they advocate for creating a

trauma-informed environment across the school re-

gardless of the fact of previous traumatic experiences

of the majority of students if any.

Implementing trauma-informed practices in

schools plays an important role in creating a wel-

coming environment for those who experienced

a different scale of traumatic events (Berger and

Martin, 2021). However, according to Berger and

Martin (2021), a lack of common understanding

of the notion of trauma-informed learning between

scholars and a lack of teachers’ knowledge of ef-

fective approaches to its implementation leads to a

situation, where instructors are unable to recognize

behaviour, impacted by trauma, and lack access to

resources necessary to support students. Scholars

stated the importance of raising awareness among

instructors on the need to implement comprehensive

trauma-informed strategies, make a justified choice

of those strategies, and be able to give first psycho-

logical aid in case their students need it. Berger

and Martin (2021) consider the lack of research,

dissemination, and professional training to be the

main reasons why system-wide implementation of

trauma-informed learning is not introduced.

The author of this paper agrees on the importance

of adopting a comprehensive approach to preparing

pre-service teachers grounded in research-evidenced

practices and practices supported by evidence, as well

as the provision of continuous professional training

for in-service teachers.

Jakobson (2021) studied how trauma-informed

school frameworks are used to support the social and

emotional needs of learners and made a very similar

conclusion. The scholar dwells on the successful ex-

amples of teaching students regulation skills and the

importance of building strong relationships between

students and teachers as an initial step in proceeding

with instruction.

Analysis of previous research shows that scholars

have been consistently advocating for the implemen-

tation of a system-wide trauma-informed approach

and appropriate professional teacher training (Berger

and Martin, 2021; Jakobson, 2021).

Research on the practices of implementing the

trauma-informed approach in school settings gives in-

sights into how a system of implementing the trauma-

informed approach across the school might look like.

Trauma-informed practices in school settings

comprise six elements, such as district-level sup-

port, school support, educators’ competence, trauma-

informed classrooms, community support, regulation

and support systems (Morton and Berardi, 2018).

Scholars indicate that trauma-informed practices only

work in their correlation and thus enhance each of its

elements.

Based on the phenomenological study, Choice-

Hermosillo (2020) grounds the conditions of the suc-

cess of trauma-informed practices in education set-

tings in five domains: Relational Trust and Class-

room Community and Culture; Emotional and Physi-

cal Regulation; System-level Support: Purposeful Im-

plementations; System-level Support: Backgrounds,

and Teacher Coaching; and Accountability with Com-

passion. Choice-Hermosillo (2020) highlights the im-

portance of the implementation of Social and Emo-

Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions on Implementing the Trauma-Informed Approach in Educational Institutions

131

tional Approach to teaching, delivering continuous

professional development of school staff, as well as

providing support for teachers working with trauma-

tized children.

This scholarly research provides for some of the

implications: it is important to prepare pre-service

teachers to work with children having trauma or men-

tal health issues; it is necessary to create school-wide

culture of trauma-informed practices to ensure suc-

cess of trauma-informed practices by carefully de-

signing the correlations between each of its elements.

2.2 Attitudes of Teachers to the

Implementation of

Trauma-informed Practices

In this section, the author analyses findings of re-

search related to studying the attitudes of teachers to

the implementation of trauma-informed approach in

their classrooms or school-wide.

Veach (2021) in a qualitative case study of ele-

mentary educators’ attitudes and perceptions towards

working with students impacted by trauma showed

staff has a positive perception of trauma-informed

practices. However, participants of the study indicate

their attitudes have changed over time as a result of

a series of professional development events and col-

laborative activities with other staff whose primarily

responsibilities is working with traumatized students.

The author of this paper finds it important to de-

velop a complex approach to building the matrix of

the implementation of the trauma-informed approach

with a diversity of perspectives from professionals in

various areas, including classroom teachers, subject

teachers, psychologists, leadership, nurses, and spe-

cial education teachers.

Vincent (2020) examined the perceptions of ed-

ucators towards trauma-informed practices in school

settings and the findings show that more than 66%

of respondents (N=61) strongly agree with the im-

portance of trauma-informed strategies. However,

the same amount of respondents indicated they did

not have any instruction on trauma-informed prac-

tices in their licensure preparation. At the same time,

only around 5% of participants perceive themselves

as those who mastered trauma-informed practices.

The result of this research shows the importance

of the introduction of trauma-informed studies in pre-

service teacher preparation and further developing in-

serve teachers’ expertise in the area. Among some

of the attempts to bring trauma-related issues into

the in-service practice of elementary school teachers

the author’s attention is drawn to Drymond’s study.

Drymond (2020) has studied the perceptions of ele-

mentary school teachers to address the mental health

needs of students through trauma-informed practices.

The participants of the study (N=299) demonstrated

some confidence in responding to the mental health

problems of their students. However, they reported

low levels of efficacy in recognizing signs of men-

tal health issues, referring students to get specialized

support and discussing mental health issues with care-

givers (Drymond, 2020).

This study once again confirms the need to destig-

matize mental health education among practitioners

with a focus on the educational perspective.

Among the studies incorporating intervention in

the form of educating on the trauma-informed ap-

proach implementation, the author’s attention is

drawn to Mikolajczyk’s (Mikolajczyk, 2018) and

Metzinger’s (Metzinger, 2021). Mikolajczyk (2018)

has studied perceptions of knowledge, competence,

school climate and program effectiveness during and

after participation in a trauma-informed care profes-

sional development. The study shows that with more

knowledge and training on trauma-informed prac-

tices, participants have only slightly increased their

perceived knowledge and competence.

Metzinger’s study has a similar aim to Mikola-

jczyk’s and focuses on investigating the perceptions

of trauma in the classroom and the levels of trauma

awareness among primary and secondary teachers.

One of the major findings in Metzinger’s study shows

that elementary school teachers implement a signif-

icant number of trauma-informed strategies in the

classroom (Metzinger, 2021). However, their per-

ceived self-efficacy was relatively moderate.

This leads to the conclusion that providing in-

service teachers with professional development train-

ings does not always lead to desired outcomes of be-

coming better trauma-informed teachers.

Hence, it is important to suggest pre-service

teachers with systemic knowledge of trauma-

informed practices rather than covering the gaps

of their knowledge with individual training ses-

sions. Moreover, the analysis of scholarly research

has shown that pre-service teachers’ perspectives on

their perceived awareness of the trauma-informed ap-

proach.

Overall, educators positively perceive trauma-

informed practices in schools. At the same time,

they indicate some gaps in their knowledge and skills

in implementing trauma-informed practices. These

findings raise the importance of building a system

of pre-service and in-service teacher training to build

trauma-informed educational settings.

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

132

3 METHODOLOGY

This paper aims to identify pre-service teachers’ per-

ceived awareness of trauma and its impact on stu-

dents. The research is guided by the following re-

search question How do pre-service teachers perceive

their knowledge, and competence in implementing

trauma practices in educational settings?

The author has adopted Mikolajczyk’s (Mikola-

jczyk, 2018) study methodology (study tool and anal-

ysis framework). However, the author of this paper

has modified the procedure and the research question

for pre-service teachers as a target group.

3.1 Participants of the Study

The study was carried out in February-May 2023 in

Ukraine, which is amidst full-scale war. The survey

was administered on a non-probability sample. The

criteria for inclusion were being pre-service teachers

of any major (N=54).

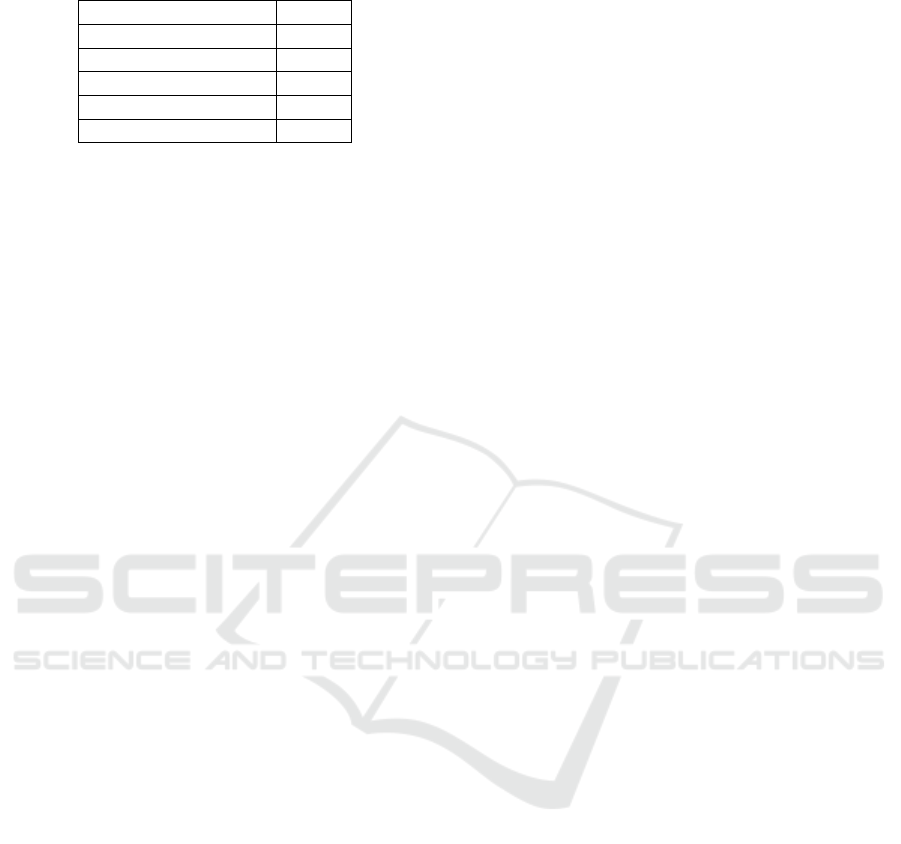

Table 1 shows the demographic data of partici-

pants. All of them have no prior teaching experience.

98.1% of them identified themselves as women and

1.9% as non-binary. The Ukrainian system of pre-

service teacher training is a binary concurrent model

represented by the university and non-university sec-

tors. Pre-service teacher training comprises simulta-

neous theoretical instruction and pedagogical training

and internship in the workplace (Kotenko and Holo-

vatenko, 2020). 64.8% of participants have no formal

pedagogical experience, 11.1% of participants have

been associated with early childhood education in-

stitutions in any capacity, and 24.1% of respondents

have been associated with primary education insti-

tutions. Respondents indicated only 9.3% of them

received training in crisis response and/or trauma.

The training they mentioned was an online course on

working with internally displaced children, teaching

in times of crisis, crisis and trauma response training,

and having prior medical education.

3.2 Data collection and analysis plan

The quantitative data in this paper was obtained

through the adapted survey developed by Mikolajczyk

(2018). The survey tool has 13 questions to iden-

tify students’ perceived knowledge and competencies

through the Likert scale tool. The survey was tailored

to the needs of pre-service teachers.

Participants were asked to share their opinion on

knowledge about the prevalence of trauma, and their

perceived competence in working with traumatized

children. The survey was grounded in ARTIC scale

Table 1: Demographic data of participants.

Type of data Frequency Percent

Gender identification

Woman 53 98.1%

Man 0 0

Non-binary 1 1.9%

Prefer not to answer 0 0

Including this year, how many years of

teaching experience do you have?

No teaching experience 54 100%

1-3 years 0 0

Type of educational institution you are affiliated

with during the internship

No formal

pedagogical experience

35 64.8%

Early childhood education

institutions, ISCED 0

6 11.1%

Primary education

institutions, ISCED 1

13 24.1%

Have you ever had training in crisis

response and/or trauma?

Yes 5 9.3%

No 49 90.7%

(Attitudes related to trauma-informed care). Partic-

ipants could choose their answer on a scale from 1

(Strongly disagree) to 5 (Always true of me). The

survey was distributed in Google Forms and data was

transferred to Excel, where it was analyzed. ‘Strongly

disagree’ was coded as 1, ‘Disagree’ was coded as 2;

‘Neither Disagree nor Agree’ was coded as 3, ‘Agree’

was coded as 4; and ‘Strongly agree’ was coded as 5.

The author checked the internal reliability of the tool

using Alpha Cronbach α=0.760, which showed its ac-

ceptable level of tool consistency (Taber, 2018). The

data analysis details are provided in the next section

of this paper.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

This study aimed to investigate what perceptions pre-

service teachers have related to their knowledge and

competence around trauma-informed approach to ed-

ucation. In this section the author presents the re-

search results and their implications for practice.

The first component of teachers’ perceptions the

author wants to identify is their knowledge about

trauma. The hypothesis is that pre-service teachers

do not have formal instruction on trauma, but due to

the unique Ukrainian context, they to some extend ei-

ther empathise students or use knowledge about their

experiences to understand their students.

Table 2 illustrates pre-service teachers’ percep-

Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions on Implementing the Trauma-Informed Approach in Educational Institutions

133

Table 2: Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of own knowl-

edge base of trauma.

Descriptive statistics Value

Mean 3.629

Median 3.714

Mode 3.857

Standard Deviation 0.975

Skewness -0.599

tions of their own knowledge about trauma. Partic-

ipants were asked 7 questions about their perceived

knowledge about the impact trauma can have on

a child or adolescent’s academic success; their be-

haviour; about different types of trauma; about the

ways that violence and traumatic experiences can lead

to mental health and co-occurring disorders; ways

staff should take into account how students’ learning

difficulties should be accommodated at educational

institutions; about reasons of students’ behaviour;

about how to get help if the teacher is struggling.

On average, pre-service teachers are not sure if

they know about different types of trauma, ways

that violence and traumatic experiences influence stu-

dents, learning and behavioural difficulties students

might have because of trauma, and how working

with students having traumatic experiences influences

teachers. The mean, median and mode of the data in-

dicate that participants do not percept their knowledge

as noteworthy. Negative skewness indicates that the

data is unevenly skewed to the left, which means that

a relatively high number of participants’ answers lies

below the mean value.

One of the main results of the study is pre-service

teachers have rather mixed opinions on their knowl-

edge of trauma. If comparing the mean in this domain

with the pre-test in Mikolajczyk (2018), the latter is

smaller (3.21) than in this study (3.629). One of the

reasons for that the author sees in the study settings.

This study is set in Ukraine, which is in the middle

of a full-scale war with constant shellings of all set-

tlements where both instructors and students are trau-

matized. In an intuitive way, pre-service teachers feel

they are more knowledgeable about trauma compared

to participants of the school staff in a peaceful coun-

try. At the same time, it should be mentioned that the

variety and intensity of various types of trauma par-

ticipants are expected to face their students exhibiting

are also slightly different.

At the same time, this result indicates that

Ukrainian pre-service teachers are ready to learn

about trauma-informed practices and the issue of im-

plementation of a unit or a course on trauma-informed

practices is of great importance and urgency. The im-

portance of the inclusion of trauma-informed training

in pre-service teacher training is actualized by Berger

and Martin (2021), Morton and Berardi (2018), Vin-

cent (2020) and other scholars.

Based on the questions in the survey tool and par-

ticipants’ answers, the author suggests teaching the

basics of the trauma-informed approach to pre-service

teachers based on the following topics:

• The notion of trauma-informed approach to edu-

cation;

• The neurobiology of trauma and its impact on

people;

• Classroom management as a way to regulate indi-

vidual students;

• Classroom management as a way to create a

trauma-informed classroom space;

• Approaches to building the trauma-informed sup-

porting school environment.

Another component of the study of pre-service

teachers’ perceptions of implementing the trauma-

informed approach is their perceived competence.

Participants were asked 6 questions on their abil-

ity to explain to students what trauma is, including

the effects of an event; their ability to recognize the

signs of trauma, even if the student does not verbally

express them; ability to establish trust and safety as

a priority in their work with students; being comfort-

able discussing or explaining trauma to others; ability

to impact a student’s behaviour in a positive way re-

gardless of how they are raised; being able to focus

on student strengths.

The analysis of descriptive statistics on the per-

ceived competence of pre-service in trauma-informed

practices is demonstrated in table 3. On average, par-

ticipants see themselves as relatively competent in ex-

plaining students what trauma is and its effect on stu-

dents, recognizing the signs of trauma, establishing

trust and safety in their work, influencing students’

behaviour in a positive way, identifying and incorpo-

rating students’ strengths and interests in the learning

process, presenting information using various modal-

ities, and being comfortable discussing and explain-

ing trauma to others. However, the data is distributed

asymmetrically with a slight left skewness indicating

there is a slightly higher number of participants with

perceptions slightly below the mean value.

The comparison of pre-service teachers’ percep-

tions of their knowledge and competence indicates

that participants, on average, feel slightly more com-

petent in their practices than in their knowledge of

trauma. However, the standard deviation for knowl-

edge (0.975) is slightly higher than for competence

(0.881), which means there is more variability in

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

134

Table 3: Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of their own

competence in trauma-informed practices.

Descriptive statistics Value

Mean 3.805

Median 3.75

Mode 3.5

Standard Deviation 0.881

Skewness -0.377

the perceptions of knowledge compared to compe-

tence. Comparing the skewness values shows that

the skewness for competence (-0.377) is smaller

than that of knowledge (-0.599), meaning a slightly

more balanced distribution for competence percep-

tions. Hence, the perceived competence of partici-

pants is slightly higher than their knowledge about

trauma.

This result shows lack of correlation between stu-

dents’ perceived knowledge about trauma response

and their perceived competence in implementing the

trauma-informed approach. The author thinks this

might be due to the fact that pre-service teachers

themselves are in the situation of trauma and a lot

of teacher trainers use trauma-informed strategies in

preparing pre-service teachers. However, this case

should be further researched.

The mean in the perceived competence domain in

Mikolajczyk’s (Mikolajczyk, 2018) pre-test is higher

(3.91) than in this study (3.805). The author that

school staff, who are participants in Mikolajczyk’s

study have more experience directly being involved

with traumatized children. According to Drymond

(2020), Metzinger (2021), and Veach (2021), even ex-

perienced teachers mention they lack support in iden-

tifying suitable trauma-informed practices and pro-

viding help to their students.

Overall, pre-service teachers have rather mixed

perceptions of their knowledge and competence re-

garding trauma-informed practices in education set-

tings. These findings are supported by previous

studies. However, having average or above-average

knowledge of trauma-informed practices and feeling

relatively competent in implementing them is a good

starting point for introducing a unit or a course on

trauma-informed practices for pre-service teachers.

5 LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

These findings might be useful in developing univer-

sity curriculums, syllabi, and/or individual units on

trauma-informed practices in education. However, the

study has several limitations the author would like to

discuss. One of the greatest limitations of the study

is its sample. The non-probability sample in this

study might not be representative of the target pop-

ulation enough to generalize the results of the study.

Hence, administering the study for a larger sample is

one of the prospects of further studies. Another lim-

itation is due to the Likert scale survey used in this

study. Data collection depended solely on partici-

pants’ understanding of statements and their sincerity

in their answers. Participants might have also avoided

extreme answers in the tool. The prospects for the

following research on the perceptions of respondents

regarding trauma-informed practices is employing a

mixed-method research design.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This research aimed at identifying perceptions of pre-

service teachers on their knowledge and competency

in implementing trauma-informed practices. From

the research that has been carried out, it is possible

to conclude that pre-service teachers have mixed per-

ceptions of their knowledge about trauma. They show

varying levels of confidence in their knowledge about

different aspects of trauma, its impact on students and

behavioural difficulties associated with trauma.

Despite their mixed perceptions of knowledge

around trauma, pre-service teachers feel relatively

competent in implementing some trauma-informed

practices. They expressed confidence in areas such as

explaining trauma to students, establishing trust and

safety, influencing positive behaviour and incorporat-

ing students’ strengths and interests.

However, variability in participants’ answers sug-

gests the need for the implementation of trauma-

informed practices into the syllabi and curricula of

pre-service teacher training. The findings suggest that

pre-service teachers are ready to learn about trauma-

informed practices and it is necessary to incorpo-

rate trauma-informed teaching as an approach to pre-

service teacher training and as a subject matter.

The author suggests teaching pre-service teach-

ers the following topics on the trauma-informed ap-

proach: The notion of the trauma-informed approach

to education; The neurobiology of trauma and its im-

pact on people; Classroom management as a way

to regulate individual students; Classroom manage-

ment as a way to create a trauma-informed class-

room space; and Approaches to building the trauma-

informed supporting school environment. These top-

ics can both give students the foundations of the

trauma-informed approach and form necessary skills

and attitudes to implement this approach in their

classroom.

Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions on Implementing the Trauma-Informed Approach in Educational Institutions

135

The findings are of direct directorial relevance

for all providers of pre-service teacher training.

Further research on comparing pre-service and in-

service teachers’ perceptions and attitudes of trauma-

informed practices is necessary. Continuing research

into the design and outline of curriculum preparing

pre-service teachers to implement trauma-informed

practices in Ukraine is fully justified because there is

a need to adapt successful foreign practices to local

realities and war settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to express her gratitude to par-

ticipants of the study and the time they committed to

the survey. This study was made possible with the in-

formational support of libraries of the University of

Minnesota Twin Cities, where the author was a visit-

ing scholar in 2022-2023 academic year.

REFERENCES

(2023). Centre of the psychological health and psychosocial

support of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla

Academy. https://www.ukma.edu.ua/index.php/sc

ience/tsentri-ta-laboratoriji/cmhpss.

(2024). War in Ukraine: Support for children and families.

https://www.unicef.org/emergencies/war-ukraine-pos

e-immediate-threat-children.

Berardi, A. and Morton, B. (2019). Trauma-Informed

School Practices: Building Expertise to Transform

Schools. George Fox University Library. https:

//open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/718.

Berger, E. and Martin, K. (2021). Embedding trauma-

informed practice within the education sector. Jour-

nal of Community & Applied Social Psychology,

31(2):223–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2494.

Choice-Hermosillo, M. (2020). Pivotal perceptions: A Phe-

nomenological exploration of trauma-informed prac-

tices in an urban school. PhD thesis, Morgridge Col-

lege of Education, Teaching and Learning Sciences,

Child, Family, and School Psychology. https://digita

lcommons.du.edu/etd/1736/.

Drymond, M. J. (2020). Examining role breadth, effi-

cacy, and attitudes toward trauma-informed care in

elementary school educators. A thesis submitted in

partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree

of Education Specialist, University of South Florida.

https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/8444/.

Forbes, H. T., Maki, D., and Lavoie, R. D. (2020). Class-

room180: A Framework for Creating, Sustaining, and

Assessing the Trauma-Informed Classroom. Beyond

Consequences Institute.

Jakobson, M. (2021). An exploratory analysis of the neces-

sity and utility of trauma-informed practices in edu-

cation. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Edu-

cation for Children and Youth, 65(2):124–134. https:

//doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2020.1848776.

Khoruzha, L., Bratko, M., Hrynevych, L., Bozhynskyi, V.,

Nikolayev, Y., and Riy, H. (2023). Organization of the

educational process in Kyiv schools during the war.

Analytical report, Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University,

Kyiv. https://don.kyivcity.gov.ua/files/2023/3/31/p2.

pdf.

Kotenko, O. and Holovatenko, T. (2020). Models of for-

eign language primary school teacher training in the

EU. In Jankovska, A., editor, Innovative scientific re-

searches: European development trends and regional

aspect, pages 92–115. Baltija Publishing. https://doi.

org/10.30525/978-9934-588-38-9-5.

Metzinger, R. E. (2021). Teacher perceptions of inter-

nal and external student behaviors and the impact

of trauma-informed practices. Dissertation in Par-

tial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree

of Doctor of Education in Leadership and Profes-

sional Practice, Trevecca Nazarene University. https:

//www.proquest.com/openview/2c2b1084ce86be5a25

83fecb4c805309/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

&diss=y.

Mikolajczyk, E. (2018). School Staff Perceptions of a

Trauma Informed Program on Improving Knowledge,

Competence, and School Climate. Dissertation Sub-

mitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for

the Degree of Doctor of Psychology, Philadelphia

College of Osteopathic Medicine. https://digitalcom

mons.pcom.edu/psychology dissertations/473/.

Morton, B. M. and Berardi, A. (2018). Creating a Trauma-

Informed Rural Community: A University–School

District Model. In Reardon, R. M. and Leonard, J.,

editors, Making a Positive Impact in Rural Places:

Change Agency in the Context of School-University-

Community Collaboration in Education, pages 193–

213. Information Age Publishing.

Operational Data Portal (2024). Ukraine Refugee Situation.

https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine.

SAMHSA (2023). Understanding Child Trauma. https:

//www.samhsa.gov/child-trauma/understanding-child

-trauma.

Taber, K. (2018). The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When

Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in

Science Education. Research in Science Education,

48(6):1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-0

16-9602-2.

Ukrinform (2023). Ukraine has officially registered

4,867,106 displaced people. https://www.ukrinfor

m.ua/rubric-society/3649695-v-ukraini-oficijno-zar

eestruvali-4-867-106-pereselenciv.html.

Veach, J. A. (2021). Childhood Trauma: A Qualitative

Case Study of Elementary Educators’ Attitudes and

Perceptions. A dissertation submitted in partial ful-

fillment of the requirements for the degree of Doc-

tor of Education, Washington State University. https:

//doi.org/10.7273/000001863.

Venet, A. S. (2021). Equity-centered trauma-informed edu-

cation. W.W. Norton & Company.

ICHTML 2023 - International Conference on History, Theory and Methodology of Learning

136

Vincent, S. (2020). Educator perceptions in relation to the

implementation of trauma-invested instructional prac-

tices. PhD thesis.

Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions on Implementing the Trauma-Informed Approach in Educational Institutions

137