Customer Attachment as the Key Factor for the Sustainability and

Growth of Unorganized Indian Kirana Shops

Pradeep Alex

1

a

, Danish Hussain

1

b

and Mohd Danish Kirmani

2

c

1

CHRIST (Deemed-to-be University), Lavasa, Pune, India

2

Paari School of Business, SRM University-AP, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India

Keywords: Kirana Shops, Retail, Customer Attachment, Purchase Intent, Customer Loyalty.

Abstract: The Indian grocery retail ecosystem is multi-layered and complex. The vast geography and varying

infrastructure levels in different parts of the country demand different distribution models. The Indian retail

ecosystem is capable enough to ensure product availability even in the interior parts of the country, and we

could call the Kirana shops its backbone. The recent past has witnessed the growth of modern retail shops and

e-commerce, and they are posing challenges to Kiranas. However, Kirana stores continue to represent a large

part of total consumer goods sales in India. Since the competition is intensifying, Kirana shops have to move

upward in retail maturity instead of playing defensively. Kiranas offer distinct advantages to customers, and

some strengths are unique to these shops. Through this study, researchers identified 'customer attachment' as

a major differentiator for Kirana shops. A methodology for measuring the same was developed by employing

due procedure. Also, the impact of sub-dimensions of customer attachment on intentions to purchase from

Kirana shops was also confirmed. The study concludes that customers have a special bond with local Kirana

stores in terms of their atmosphere and staff, positively impacting the purchase intent.

1 INTRODUCTION

The retail market is evolving rapidly. The changes in

this sector are driven by multiple factors such as

digitalization, emerging consumer needs,

advancements in supply chain models, etc. In India,

the government has been gradually liberalizing the

retail sector for foreign direct investments, which is

also a reason for the ongoing transformation in this

sector (Bagaria & Santra, 2014). Kirana shops are the

basic level store format in India, which are numerous

and present in every town class as well as rural parts

of the country. In other words, Kiranas are the small

shops (Mom and Pop Shops) that contribute to the

majority of India’s $932 billion retail market (CB

Insights, 2022). They can also be described as

traditional grocery retailers or general stores.

According to estimates, there are more than 12

million Kirana shops in India (Malhotra, et al., 2022).

While there have been discussions about the future

dominance of large organized retailers and e-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5308-9473

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7617-3280

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9641-8326

commerce in the Indian retail market, Kiranas

continue to contribute more than 75% of India’s

consumer goods sales. That being said, with the

growth of modern retail formats, the share of these

small mom-and-pop shops has reduced over time.

This is a trend observed in other developed

economies as well (CB Insights, 2022).

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Kirana stores

played a vital role. Approximately 90% of fast-

moving consumer goods sales in India occur through

them, engaging 8% of India’s labor force and

contributing 10% to the gross domestic product (CB

Insights, 2022). This underscores the economic

importance of Kirana shops, ensuring better income

distribution and economic equality. In the local

neighborhood, the crucial role played by Kirana

shops during the Covid-19 pandemic highlights

customer dependency on these stores to meet their

daily requirements. However, the need to upgrade or

modernize Kirana shops persists. Large retail

companies like Amazon, Reliance, etc., and

Alex, P., Hussain, D. and Kirmani, M.

Customer Attachment as the Key Factor for the Sustainability and Growth of Unorganized Indian Kirana Shops.

DOI: 10.5220/0012678400003882

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies (PAMIR-2 2023), pages 117-126

ISBN: 978-989-758-723-8

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

117

renowned startups backed by top-tier investors are

attempting to onboard or form tie-ups with Kiranas.

Consequently, fast-moving consumer goods

companies are closely monitoring the actions of these

large retailers and seeking to partner with them

through strategic alliances, acquisitions,

collaborations, etc., to secure their space in Kirana

shops (CB Insights, 2022).

1.1 Small Is Big, How to Make It

Bigger?

Kirana shops, despite being unorganized, play a vital

role in the social and economic ecosystem of India.

Typically owned and managed by lower or middle-

income groups in society, the sustainability of these

shops is crucial for social equilibrium. These small

shops conduct a significant volume of business. With

the establishment of large retail chains and the rise of

online commerce in India, many researchers

suggested that Mom and Pop shops should integrate

with large online retailers for their survival. However,

it is essential to approach this situation from the

perspective of Kiranas. Are the 12 million-plus Indian

Kirana shops in a vulnerable position with the entry

of organized retailers and e-commerce? Or is it a

necessity for e-commerce giants to onboard Kirana

shops for their expansion and growth? In this study,

researchers aim to answer these questions through the

lens of Kirana shops. The objective of this study is to

identify the unique strengths and differentiators of

Kirana stores in India.

1.2 The Changing Paradigm

One change observed in the recent past is that, due to

the Corona pandemic, people engaged in pantry

loading and bulk buying products, resulting in the

scarcity of national brands in stores. Consumers were

consequently forced to purchase private label brands.

Throughout this process, consumers recognized that

private label brands are economical, and due to their

ready availability, they continued to favor these

brands. This shift also helped consumers alleviate

financial stress during the unpredictable Covid-19

period (Palea, A., 2020).

Availability challenges led to brand switching,

and in the United States of America, approximately

75% of consumers explored new brands or products

due to the unavailability of their regular choices

(Charm, T. et al., 2020). Additionally, e-grocery has

emerged as a new trend. During the Covid-19 days,

many consumers started buying groceries from online

channels, and they intend to continue this practice

even after returning to normalcy (TjonPianGi and

Spielvogel, 2021). Moreover, with the Covid-19

pandemic, the use of digital payments and digital

wallets has increased, and customers have

experienced the convenience of such transactions.

This positive experience has led them to continue

embracing cashless transactions (Talwar, et al., 2020).

It is a fact that Covid-19 has transformed the mode

of purchasing for consumers. The changes in

consumer buying behaviour can be summarized

under three points:

In urban domiciles, local retailers began

delivering basic grocery items to customers' homes

due to lockdowns, people in quarantine, etc.

Customers felt more secure, and they realized the

value of the local ecosystem (Charm, T. et al., 2020).

Growth of private label brands can be attributed

to two reasons:

In developed and emerging markets, customers

felt insecure about their future income streams,

prompting a shift towards cost-effective products and

services.

During the lockdown, due to the shortage of

national brands, customers tried private label brands

and discovered that they are not inferior to the

expensive national brands (Begley & McOuat, A.,

2020).

Growth of online buying and digital payments -

New customers are engaging in online purchases.

Once they get used to it, they may continue the

behaviour due to its convenience (Talwar, S. et al.,

2020).

These changing trends are creating a more

favourable situation for the growth of e-commerce.

Studies confirm synergies between Kirana and e-

commerce, suggesting the integration of these small

shops into a large e-commerce ecosystem, benefiting

both (Sinha, P. K., Gokhale, S., & Rawal, S., 2015).

Onboarding the unorganized 12 million retailers

could enhance the efficiency of the e-commerce

giants' supply chains. However, a potential threat is

the consolidation of the Indian retail industry into a

few hands. For this reason, instead of solely focusing

on synergies between e-commerce and Kiranas,

efforts should be directed towards identifying areas

where Kiranas can improve to meet future customer

expectations and become more competitive.

There are several factors that are considered

specific to Kirana stores such as ease of access, the

ability to sell the most locally relevant assortment of

goods, free delivery, and credit facilities for regular

customers etc. (The Hindu Business Line, 2021).

While these capabilities can be developed by other

retail formats, one unique strength that Kirana shops

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

118

possess, which is challenging for other retail formats

to replicate, is the 'personal connect.'

Nowadays, discussions mainly revolve around

automation, artificial intelligence, robotics, chatbots,

etc., and implementing these technological enablers

in our businesses can lead to a reduction in operating

costs. However, the missing element in this

transformation is the 'Personal Connect.' The 'Human

Connect' is anticipated to become rare and costly in

the coming years. Numerous examples illustrate that

brands focusing on emotions in their communication

experienced increased customer response and sales

growth, particularly among millennials (Magids, S.,

Zorfas, A., & Leemon, D. 2015). Looking ahead, the

cost of a personal connection is expected to be much

higher compared to a technology-enabled connection.

For instance, when a customer service executive

handles a customer query, the communication

involved is likely to be more costly than handling the

query through a chatbot. As the cost of human

connection rises, its uniqueness and value will also

increase. This personal connection could serve as a

differentiator for Kirana shops, as most of these shops

are managed by the shop owner, who is a familiar face

for the customer. In this study, researchers aim to

understand the impact of human connections in

Kirana shops.

1.3 Need for a Dedicated Study Around

Customer Attachment with Kirana

Shops

A notion extensively deliberated by both practitioners

and academicians revolves around the synergies

between Kirana shops and e-commerce. The

discussion often centers on how these two formats

can complement each other. However, a crucial

aspect lacking in these studies is whether, when these

two formats come together, both will derive the same

level of benefits in the short and long term. Initial

assessments suggest that organized players may

possess better negotiation power, potentially tipping

decisions in their favor. Therefore, in addition to

discussing synergies between Kiranas and e-

commerce, it is equally important to consider how

Kiranas can compete with e-commerce. This involves

exploring the competencies that these small mom-

and-pop shops should possess.

Attachment is one element that can provide a

differentiated advantage to Kiranas. However, there

should be data-based evidence of this attachment, and

currently, this area of study is lacking. Confirming the

level of attachment with Kirana shops will help to

determine whether attachment can be a differentiator

for these small retail shops.

Many studies have validated that affordability and

availability are the key differentiators of Kirana shops

(Atul, K., & Sanjoy, R., 2013; The Hindu Business

Line, 2021). However, these advantages can

potentially be eroded, as any other retail format can

develop them by strategically investing in these areas.

Simultaneously, the social and personal connection

that Kirana shops have with their customers could

provide them with a distinct advantage. In the case of

modern retail and e-commerce formats, the personal

connection is often absent. A dedicated study on

customer attachment to Kirana shops can offer more

insights into the relationship customers have with

these retail shops. Furthermore, depending on the

level of customer attachment, these mom-and-pop

shops can formulate strategies and enhance core

competencies to remain relevant in the evolving retail

environment.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Qualitative methods were employed in the initial

phase of the study. Employing an ethnographic

approach, the researchers visited various Kirana

shops to observe the interactions between customers

and various elements within the stores, including

employees, other customers, and the shop owner.

This approach was instrumental in confirming the

high and noticeable level of interaction that customers

have with different aspects of the store. Based on

these observations, the researchers identified

important benefits and value additions that Kirana

stores offer to their customers, including comfort,

convenience, trust, credit, product knowledge,

product recommendations, and, most importantly, the

interaction between customers and other individuals

present in the store. These interactions can be

hypothesized to form a robust emotional connection

between the customer and the Kirana shop,

potentially materializing in the form of an attachment

to the shop. In the second phase of the study,

researchers collected primary data and utilized

Exploratory Factor Analysis, Confirmatory Factor

Analysis, and regression methods to confirm

customer attachment with the Kiranas.

2.1 Item Generation

As discussed in the previous section, researchers

identified 'Attachment' as a key potential

differentiator of the Kirana shops. The objective of

Customer Attachment as the Key Factor for the Sustainability and Growth of Unorganized Indian Kirana Shops

119

this study was to confirm the same. However, no

standard scale was available in the existing literature

to measure these factors. Therefore, it was decided to

develop a scale adopted from similar studies and

qualify the items. Most of the 'Attachment factors'

were adopted from Brocato, E. D., Baker, J., &

Voorhees, C. M. (2015). It was also important to

review the questionnaire for question wording, ease

of understanding, and other inconsistencies. Based on

feedback from colleagues who are experts in the field

of consumer research, some of the items were

rephrased to make them more relevant. Researchers

included the following factors as the lead indicators

of attachment.

2.1.1 Nostalgia

Nostalgia is defined as a subset of autobiographical

memories involving reflections on past objects,

persons, or experiences that are positive (Hirsch

1992). These memories connect an individual’s life

path to the places in which these experiences occur

and are primarily concerned with a need for

attachment (Braun-LaTour et al. 2007). Since

nostalgia involves recollecting past incidents and

events in an individual's life, if a customer has

nostalgic feelings about Kirana shops, it indicates a

certain level of attachment with the store.

2.1.2 Place Dependence

Place dependence is defined as an individual’s

evaluation of the environment in terms of its

functionality in satisfying unfulfilled needs

(Backlund and Williams 2003). Stokols and

Shumaker (1981) argue that the greater the number

and range of needs met by a place, the more positive

individuals' feelings will be toward that place.

Therefore, researchers considered place dependence

as a measure of attachment with the store.

2.1.3 Social Bonds with Employees

A social bond with employees, while significant, is

considered the least important driver of place

attachment. However, service quality is a significant

driver of place attachment (Brocato, E. D., Baker, J.,

& Voorhees, C. M., 2015). Since a bond with

employees is an indicator of service quality, which, in

turn, leads to place attachment, researchers included

items to measure social bonds with employees.

2.1.4 Social Bonds with Customers

When retail store managers aim to create place

attachment, focusing on improving the physical

aspects of a location is not sufficient. They must

consider the entire "place," including social elements

that can enhance the strength of attachment customers

feel toward a firm (Brocato, E. D., Baker, J., &

Voorhees, C. M., 2015). While designing the physical

environment may often be a focus for service firms,

intentionally designing the social experience,

involving both employees and other customers, may

represent a new perspective for many firms (Brocato,

E. D., Baker, J., & Voorhees, C. M., 2015). The

overall social connection happening at a store may

lead to attachment with that shop, and if this holds

true, Kirana shops can leverage it the most because

the customers of Kirana shops are mostly from the

same locality. However, space constraints for better

social interactions may be a bottleneck for Kiranas.

2.1.5 Strength of Social Attachment

Place attachment differs from attachments to tangible

goods brands because it encompasses social

relationships that can form within a place. To enhance

social bonds, which are crucial to the strength of

social attachment, a shift in service orientation may

be necessary (Brocato, E. D., Baker, J., & Voorhees,

C. M., 2015). In atmosphere-dominant service firms,

where applicable, managers should strive to

encourage interaction between customers. One way to

achieve this may be to create events in which

customers participate together in activities (Brocato,

E. D., Baker, J., & Voorhees, C. M., 2015). Although

Kirana shops may not be classified as atmosphere-

dominant service firms, if social connection plays a

role in creating attachment with a store, it needs to be

considered for Kiranas as well, even if its impact is

relatively low in the case of these mom-and-pop

shops.

2.1.6 Place attachment

In addition to social attachment, place attachment

incorporates the feeling of connection to the physical

dimensions of places (Hidalgo and Hernandez 2002).

The place attachment concept serves as a theoretical

foundation to evaluate critical aspects of place

because it is rooted in individuals' cumulative

experiences with both the physical and social aspects

of an environment, resulting in a strong emotional

bond with that place (Low and Altman 1992; Relph

1985; Tuan 1990, 1997). Therefore, place attachment

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

120

was also included to understand the overall customer

attachment to Kirana shops.

2.2 Scale Development

A pilot survey was initially conducted with the factors

of 'Attachment' mentioned above. Later, the items

were consolidated based on exploratory factor

analysis (EFA), and a scale for the final consumer

survey was established.

Initially, the researchers included items to

measure Social Bonds with Customers, Strength of

Social Attachment, and Place Attachment. However,

in EFA, all these items loaded under the same factor,

providing insight to the researchers that the

customer's overall experience, including the place,

people involved, and other environmental factors of

the store, is creating an impact on attachment.

Therefore, researchers merged these three factors into

one and named it 'Social Connect.'

The items under four independent variables

qualified as per the EFA are Nostalgia (NS), Place

Dependence (PD), Social Bond with Employees (BE),

and Social Connect (SC). The final survey was

conducted using the qualified items, and regression

analysis was performed to assess the impact of the

independent variables on the dependent variable,

which is Purchase Intent (PI). A total of 307 samples

were collected during the final survey.

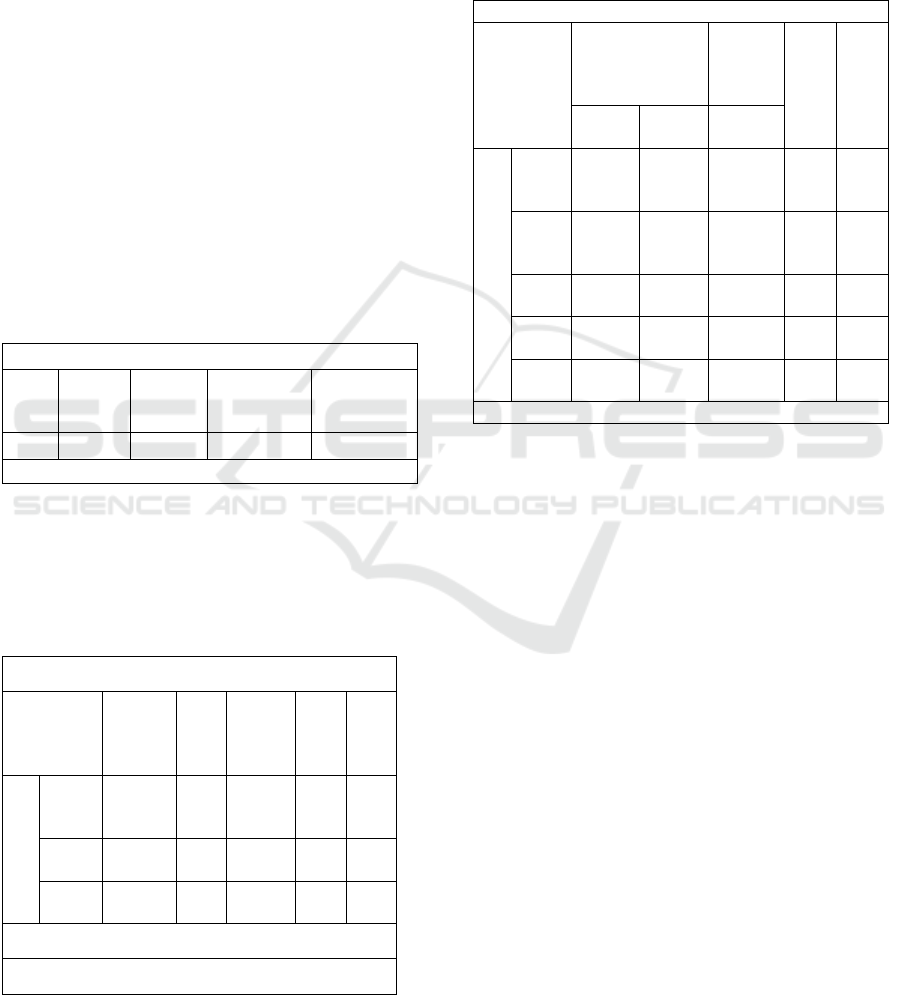

2.3 Model Development

In this study, researchers developed a model that links

Nostalgia, Place Dependence, Social Bonds with

Employees, and Social Connect to ‘Attachment’. The

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) diagram in

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between these

variables.

The RMSEA results of the model fall within the

acceptable range (RMSEA is 0.071). Researchers

have confirmed the validity of the model, as the

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) results are

consistent and qualifying.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

While this study primarily focuses on customer

attachment, it also encompasses other factors that

support Kirana shops. Analysis of the primary data

confirms that customer attachment with Kirana shops

can indeed enhance purchase intent.

Figure 1: Confirmatory factor analysis for developing

Second order construct

3.1 Viewing Kirana Shops Through the

Lens of Attachment Theory

Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby

formulated the attachment theory, explaining the

enduring psychological connectedness between

humans, initially focusing on young children but later

extending to attachment in adults. This theory

considers factors such as romantic and sexual

attraction, peer relationships at all ages, and responses

to the care needs of the sick, elderly, or infants

(Suomi, S. J., 1995). Understanding the extent to

which attachment theory can impact retailing,

especially in the socio-economic context of

developing countries, is crucial. If it does have an

impact, Kirana shops could leverage it the most,

potentially becoming a core strength that sets them

apart.

Table 1: CFA Results of the model

Model RMSEA LO

90

HI

90

PCLOSE

Default model .071 .062 .079 .000

Independence

model

.306 .299 .313 .000

Thomas, T. C et al., (2020) applied social practice

theory in their research, which conceptualizes a series

Customer Attachment as the Key Factor for the Sustainability and Growth of Unorganized Indian Kirana Shops

121

of practices guided by culture and performed

individually or collectively. Such social practices

may lead to stronger bonding between individuals or

social groups, and customers may develop such

bonding with their local Kirana shop. Identifying the

level of this attachment is essential to confirm

whether customer attachment is a key differentiator

for Kiranas.

In this study, researchers validated the level of

customer attachment to the Kirana shop through

primary data. Different factors of attachment were

identified and validated through quantitative

techniques. The analysis of primary data confirms the

level of influence of attachment factors - Nostalgia

(NS), Place Dependence (PD), Social Bond with

Employees (BE), and Social Connect (SC) on the

dependent variable Purchase Intent (PI).

In Table 2, regression analysis confirms a 58.1%

(R Square .581) change in purchase intent that can be

accounted for by the independent variables of

attachment.

Table 2: Regression Model Summary

Model Summary

Mod

el

R R

Square

Adjusted R

Square

Std. Error

of the

Estimate

1 .762

a

.581 .576 .5544256

a. Predictors: (Constant), SC, PD, NS, BE

The model fit is confirmed by the ANOVA in

Table 3, with a significance level (sig) of .000, which

is well within the acceptable range (less than the

acceptable level of .05). Additionally, the F value of

104.750 indicates that the model is considered good.

Table 3: ANOVA results

ANOVA

a

Model Sum

of

Square

s

df Mean

Squar

e

F Sig.

1 Regr

essio

n

128.79

5

4 32.19

9

104

.75

0

.00

0

b

Resid

ual

92.831 302 .307

Total 221.62

6

306

a. Dependent Variable: PI

b. Predictors: (Constant), SC, PD, NS, BE

Upon reviewing the significance level of each

independent variable, as shown in Table 4, it is

confirmed that Nostalgia is an independent variable

that does not fall within the level of significance

(Sig .249). However, all other independent variables'

significance levels fall within the acceptable range.

This suggests that Nostalgia has no significant impact

on the Purchase Intent.

Table

4: Coefficients of variables

Coefficients

a

Model Unstandardized

Coefficients

Standa

rdized

Coeffic

ients

t Sig.

B Std.

Erro

r

Beta

1 (Con

stant

)

1.322 .157 8.3

99

.00

0

NS -.071 .061 -.070 -

1.1

54

.24

9

PD .285 .057 .305 5.0

02

.00

0

BE .311 .063 .348 4.9

27

.00

0

SC .196 .048 .246 4.1

15

.00

0

a. De

p

endent Variable: PI

3.1.1 Nostalgia

Kirana shop customers are typically local, and there

is often a familiarity between the shop owner and

customers. The primary study included statements to

assess the level of nostalgia customers have with the

Kirana shop and its correlation with Purchase Intent.

Data analysis indicates that nostalgia is not impacting

purchase intent (Sig. value is .249, which is higher

than >0.05). While customers may have nostalgic

memories associated with Kirana shops, it does not

necessarily translate into purchase intention. When

making purchasing decisions, customers tend to be

practical and look for clear advantages. Nostalgia

alone is not powerful enough to influence customers'

purchase decisions.

3.1.2 Place Dependence

Place dependence explains the importance of the

Kirana shop to customers in comparison to other store

formats (Goswami, P., & Mishra, M. S., 2009).

Customers endorse that they experience greater

satisfaction when purchasing grocery items from

Kirana shops, and they consider Kirana shops the best

among all available grocery retail formats to

patronize. Many factors may contribute to this place

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

122

dependence, including the proximity of the store, the

credibility of the shopkeeper, and the quality of

products. The high place dependence and customers'

willingness to patronize Kirana shops indicate its

strength, which may be unique. Primary data analysis

confirms that place dependence impacts purchase

intent (Sig. value is .000, which is lower than <0.05).

3.1.3 Social Bond with Employees

In the case of modern retail and e-commerce formats,

there is often a lack of personal connection.

Automation addresses various customer issues, and

large retail formats are adopting new customer

handling and grievance management solutions

through technology. However, this shift may result in

customers missing personal connections. The

fundamental strength of Kirana shops lies in the

personal connections the shop staff have with the

customers. Primary data analysis indicates that the

customer bond with the store staff has a strong

correlation with purchase intent (Sig. value is .000,

which is lower than <0.05).

3.1.4 Social Connect

Social connect reflects the customer bonding with the

store atmosphere, elements of the store, and the

people working there. Customer responses indicate a

clear sense of belongingness with the store, and

customers feel that the store staff and other customers

visiting the store are like them (Johnson et al., 2015).

The social element emerges as a significant factor,

positioning Kirana shops as part of the social

environment. In contrast to other retail shops

establishing their identity as a 'business entity,' the

identity of Kirana shops is perceived as 'more of an

integral part of the society.' Therefore, maintaining

this identity is crucial for Kirana shops to differentiate

themselves from others. Based on the primary data

analysis, researchers confirm that 'Social Connect'

can positively influence Purchase Intent (Sig. value

is .000, which is lower than <0.05).

When researchers inquired about the frequency of

their visits to Kirana shops, 83% of the customers

responded that they visit nearby Kirana shops 1 to 3

times a week, while 17% of the respondents visit

more than 3 times a week. This indicates that Kirana

shops are part of the daily activity of most customers

in India.

All the factors mentioned above reflect the level

of customer attachment to Kirana shops. The crucial

point here is that these factors of customer attachment

are leading to purchase intent. This implies that these

mom-and-pop shops can leverage customer bonding

to grow their business. However, many Kirana shop

owners may not be aware of their strength or may not

realize it. It is important to create awareness about the

strength of Kirana shops so that this community of

small retailers will be better equipped to harness their

strength for business growth.

4 CONCLUSION

Understanding customer attachment begins with

identifying different touchpoints in the customer

journey. In this study, researchers mapped various

customer touchpoints and attempted to measure the

level of attachment customers have with different

store elements and people. The key insight from the

primary data analysis is that customers have a strong

personal attachment to the people working in the

Kirana shop, as well as to the place itself. This

attachment leads to more purchases. Importantly,

Kirana shops occupy a unique position in the social

system, and they should strive to maintain it as their

unique selling proposition.

It is challenging for any other retail store format

to achieve this position by replicating the elements of

Kirana shops, mainly because one major factor is that

the shop owner is typically from the society it serves.

Indian Kirana shop owners may not be forward-

looking in terms of a business growth roadmap, and

they might not be fully aware of their strengths and

weaknesses. Therefore, supporting Kirana shops to

strengthen their business by leveraging the customer

attachment factor is crucial.

This research is unique in that it brings clarity to

a key strength of Kirana shops, which is 'Attachment.'

This understanding can help the Kirana shop

community focus on its strength and leverage it. At

the same time, this study leaves an opportunity for

new researchers to explore how Kirana shops can

further leverage 'Attachment' to grow their businesses.

REFERENCES

Abhishek Malhotra, Daniel Läubli, IshitaKayastha,

MahimaChugh et.(2022). The state of retail in India.

McKinsey & Company.

Akhtar, N., Nadeem Akhtar, M., Usman, M., Ali, M., &

Iqbal Siddiqi, U. (2020). COVID-19 restrictions and

consumers’ psychological reactance toward offline

shopping freedom restoration. The Service Industries

Journal, 40(13-14), 891-913.

Anderson, R. M., Heesterbeek, H., Klinkenberg, D., &

Hollingsworth, T. D. (2020). How will country-based

Customer Attachment as the Key Factor for the Sustainability and Growth of Unorganized Indian Kirana Shops

123

mitigation measures influence the course of the

COVID-19 epidemic?.The lancet, 395(10228), 931-

934.

Arora, S., &Sahney, S. (2017). Webrooming behaviour: a

conceptual framework. International Journal of Retail

& Distribution Management, 45(7/8), 762-781.

Atul, K., &Sanjoy, R. (2013). Store attribute and retail

format choice. Advances in Management, 6, 11-27.

Backlund, E. A., & Williams, D. R. (2004). A quantitative

synthesis of place attachment research: Investigating

past experience and place attachment. In: Murdy,

James, comp., ed. Proceedings of the 2003 Northeastern

Recreation Research Symposium; 2003 April 6-8;

Bolton Landing, NY. Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-317.

Newtown Square, PA: US Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station: 320-

325..

Bagaria, N., &Santra, S. (2014). Foreign direct investment

in retail market in India: some issues and challenges.

Researchjournali’s Journal of Economics, 2(1).

Begley, S., &McOuat, A. (2020). Turning private labels

into powerhouse brands. McKinsey & Company,

accessed, 12.

Braun-LaTour, K. A., LaTour, M. S., &Zinkhan, G. M.

(2007). Using childhood memories to gain insight into

brand meaning. Journal of Marketing, 71(2), 45-60.

Brocato, E. D., Baker, J., & Voorhees, C. M. (2015).

Creating consumer attachment to retail service firms

through sense of place. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 43, 200-220.

CB Insights. (2022) Bigger than e-commerce? Digitizing

the kirana store is the biggest opportunity in Indian

retail. https://www.cbinsights.com/research/kirana-

store-india-retail.

Charm, T., Dhar, R., Haas, S., Liu, J., Novemsky, N.,

&Teichner, W. (2020). Understanding and shaping

consumer behavior in the next normal. McKinsey &

Company, 24.

Chen, H., Duan, W., & Zhou, W. (2017). The interplay

between free sampling and word of mouth in the online

software market. Decision Support Systems, 95, 82-90.

Chen, Y., &Xie, J. (2005). Third-party product review and

firm marketing strategy. Marketing science, 24(2), 218-

240.

Chiang, I. P., yi Lin, C., & Huang, C. H. (2018). Measuring

the effects of online-to-offline marketing.

Contemporary Management Research, 14(3), 167-189.

Flavián, C., Gurrea, R., &Orús, C. (2019). Feeling

confident and smart with webrooming: understanding

the consumer's path to satisfaction. Journal of

Interactive Marketing, 47(1), 1-15.

Flavián, C., Gurrea, R., &Orús, C. (2020). Combining

channels to make smart purchases: The role of

webrooming and showrooming. Journal of Retailing

and Consumer Services, 52, 101923.

Goswami, P., & Mishra, M. S. (2009). Would Indian

consumers move from kirana stores to organized

retailers when shopping for groceries?.Asia Pacific

Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 21(1), 127-143.

Greenberg, E., & Kates, A. (2013). Strategic digital

marketing: top digital experts share the formula for

tangible returns on your marketing investment.

McGraw Hill Professional.

Hemalatha, M., & Najma, S. (2013). The antecedents of

store patronage behaviour in Indian kirana store.

International Journal of Business Innovation and

Research, 7(5), 554-571.

Hidalgo, M. C., & Hernández, B. (2002). Attachment to the

physical dimension of places. Psychological reports,

91(3_suppl), 1177-1182.

Hirsch, A. R. (1992). Nostalgia: A neuropsychiatric

understanding. ACR North American Advances.

Isa, K., Shah, J. M., Palpanadan, S., & Isa, F. (2020).

Malaysians’ popular online shopping websites during

movement control order (Mco). International Journal of

Advanced Trends in Computer Science and

Engineering, 9(2), 2154-2158.

Jayasankaraprasad, C., &Kathyayani, G. (2014). Cross-

format shopping motives and shopper typologies for

grocery shopping: a multivariate approach. The

International Review of Retail, Distribution and

Consumer Research, 24(1), 79-115.

Johnson, K. K., Kim, H. Y., Mun, J. M., & Lee, J. Y. (2015).

Keeping customers shopping in stores:

interrelationships among store attributes, shopping

enjoyment, and place attachment. The International

Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research,

25(1), 20-34.

Joseph, M., &Soundararajan, N. (2009). Retail in India: A

critical assessment. Academic Foundation.

Kang, J. Y. M. (2018). Showrooming, webrooming, and

user-generated content creation in the omnichannel era.

Journal of Internet Commerce, 17(2), 145-169.

Kumar, S., &Bishnoi, V. K. (2007). Influence of marketers’

efforts on rural consumers and their mind set: a case

study of Haryana. Research in Mark ch in Mark ch in

Mark ch in Mark ch in Marketing, 80.

Kyle, G. T., Absher, J. D., Graefe, A. R., Mowen, A. J., &

Tarrant, M. (2004). Linking place preferences with

place meaning: an examination of the relationship

between place motivation and place attachment. Journal

of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 439–454.

Laato, S., Islam, A. N., Farooq, A., &Dhir, A. (2020).

Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of

the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-

response approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer

Services, 57, 102224.

Liu, L., Cheung, C. M., & Lee, M. K. (2016). An empirical

investigation of information sharing behavior on social

commerce sites.International Journal of Information

Management, 36(5), 686-699.

Low, S. M., & Altman, I. (1992). Place attachment: a

conceptual inquiry. Human Behavior& Environment:

Advances in Theory & Research, 12, 1–12.

Luarn, P., & Lin, H. H. (2003). A customer loyalty model

for e-service context. J. Electron. Commer. Res., 4(4),

156-167.

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

124

Madeleine TjonPianGi and Julia Spielvogel(2021). The e-

grocery challenge: Moving toward profitable growth.

McKinsey study

Magids, S., Zorfas, A., &Leemon, D. (2015). The new

science of customer emotions. Harvard Business

Review, 76(11), 66-74.

Manss, R., Kurze, K., &Bornschein, R. (2020). What drives

competitive webrooming? The roles of channel and

retailer aspects. The International Review of Retail,

Distribution and Consumer Research, 30(3), 233-265.

Marmol, M., &FernándezAlarcón, V. (2019). Trigger

factors in brick and click shopping. Intangible Capital,

15(1), 57-71

Mukherjee, A., Satija, D., Goyal, T. M., Mantrala, M. K.,

& Zou, S. (2012). Are Indian consumers brand

conscious? Insights for global retailers. Asia Pacific

Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 24(3), 482-499.

Orús, C., Gurrea, R., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2019). The

impact of consumers’ positive online recommendations

on the omnichannelwebrooming experience. Spanish

Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 23(3), 397-414.

Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B.,

&Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand

attitude strength: conceptual and empirical

differentiation of two critical equity drivers. Journal of

Marketing, 74(6), 1–17.

Palea, A. (2020). Glocalization Practices of Supermarket

Chains. Case Study: Food Retailers in Romania.

Journal of Mediation & Social Welfare, 2(1), 22-43.

Rathee, R., &Rajain, P. (2019). Online shopping

environments and consumer’s Need for Touch. Journal

of advances in management research.

Relph, E. (1985). In S. David & M. Robert. Geographical

experiences and being-in-the-world: The

phenomenological origins of geography. Dwelling,

place and environment, 15-31.

Sayyida, S., Hartini, S., Gunawan, S., &Husin, S. N. (2021).

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on retail

consumer behavior. Aptisi Transactions on

Management (ATM), 5(1), 79-88.

Shi, X., & Liao, Z. (2017). Online consumer review and

group-buying participation: The mediating effects of

consumer beliefs. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5),

605-617.

Sinha, P. K., Gokhale, S., &Rawal, S. (2015). Online

retailing paired with Kirana—A formidable

combination for emerging markets. Customer Needs

and Solutions, 2, 317-324.

Stokols, D. (1981). People in places: A transactional view

of settings. Cognition, social behavior, and the

environment, 441-488.

Suomi, S. J. (1995). The influence of attachment theory on

ethological studies of biobehavioral development in

nonhuman primates. Attachment theory: Social,

developmental and clinical perspectives.

Talwar, S., Dhir, A., Khalil, A., Mohan, G., & Islam, A. N.

(2020). Point of adoption and beyond. Initial trust and

mobile-payment continuation intention. Journal of

Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102086.

Thehindubusinessline. (2021) The Kirana store will remain

evergreen. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com

Thomas, T. C., Epp, A. M., & Price, L. L. (2020).

Journeying together: Aligning retailer and service

provider roles with collective consumer practices.

Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 9-24.

Tuan, Y. F. (1990). Topophilia: A study of environmental

perception, attitudes, and values. Columbia University

Press.

Tuan, Y. F. (1997). Space and Place–The Perspective of

Experience. 6. painos.

Viejo-Fernández, N., Sanzo-Pérez, M. J., & Vázquez-

Casielles, R. (2019). Different kinds of research

shoppers, different cognitive-affective consequences.

Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 23(1), 45-68.

Zhang, J. (2014). Customer'loyalty forming mechanism of

O2O E-commerce. International Journal of Business

and Social Science, 5(5).

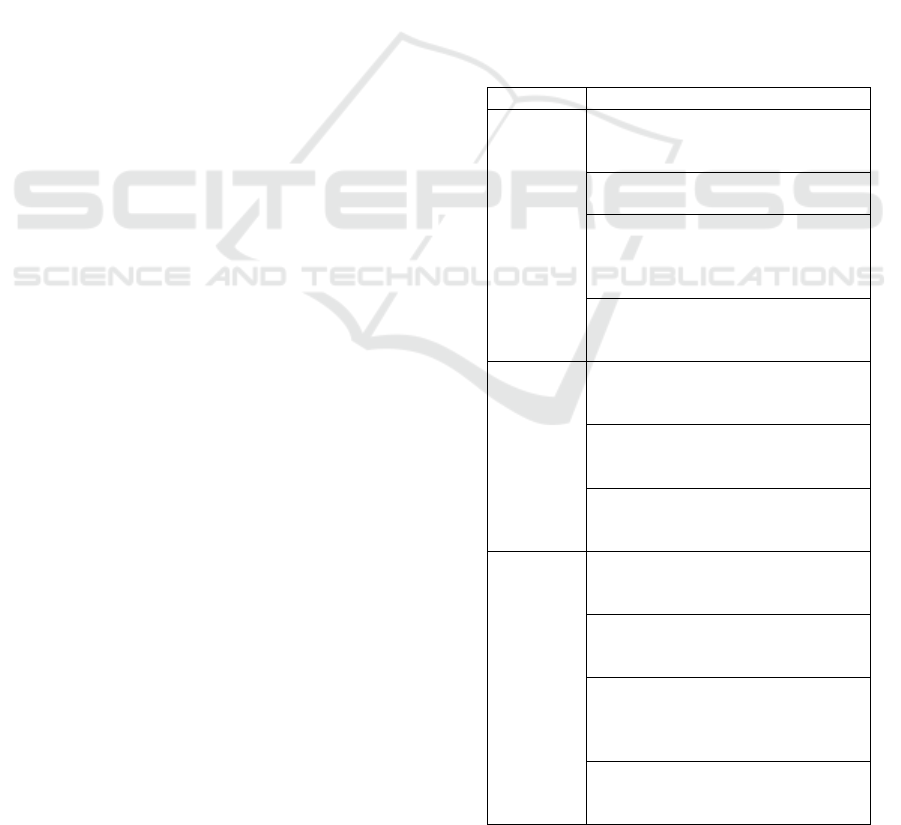

APPENDIX

Qualified items are given below:

Variable Items

Nostalgia Ns7: Visiting the Kirana Shop

makes me feel sentimental or

nostal

g

ic

Ns8: The Kirana shop reminds me

of im

p

ortant events in m

y

life.

Ns9: When I think about the Kirana

shop I visit regularly, I am

reminded about the good things that

have happened in my life.

Ns10: When I am at the Kirana

shop, I reminisce about good events

from m

y

p

ast.

Place

dependenc

e

Pd11: I get more satisfaction going

to the Kirana Shop than I get from

an

y

other sho

p

Pd:12 No other shop provides the

type of experience I have at the

Kirana Shop

Pd13: For me the Kirana shop is the

best of all available grocery retail

formats to patronize

Social

Bonds

with

employees

Be14: I feel a social connection

with the Kirana shop owner and the

staff

Be15: I have a bond with the owner

and the staff of the Kirana shop I

visit

Be16: I am not willing to consider

any other option for purchasing

because of the relationship I have

with the Kirana shop

Be17: The relationship that I have

with the owner and the staff of the

Kirana sho

p

is im

p

ortant to me.

Customer Attachment as the Key Factor for the Sustainability and Growth of Unorganized Indian Kirana Shops

125

Social

Connect

Sc18: I am not willing to go to

another Kirana Shop because of the

relationship I have with the

customers visitin

g

this Kirana sho

p

Sc19: I have a special relationship

with the customers that visit the

Kirana Sho

p

Sc20: I can’t imagine living without

the people that come to the Kirana

Sho

p

Sc21: I feel better if I am not away

from the people in the Kirana shop

for long period of time

Sc22: If the people in the Kirana

shop were permanently gone from

my life, I’d be upset

Sc23: Never being able to interact

with the people visiting the Kirana

sho

p

would be distressin

g

to me

Sc24: I really miss the Kirana shop

I visit when I am away for long

p

erio

d

Sc25: The Kirana shop reminds me

of memories and ex

p

eriences.

Sc26: I can’t imagine living without

the Kirana shop I visit

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

126