Occupational Health Implication of Covid-19 Layoffs on Airline

Ground Staff: Study on Mental Health Effects

Winda Putri Diah Restya

a

and Sri Nurhayati Selian

Psychology Faculty, Muhammadiyah Aceh University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia

Keywords: Airlines Industry, Covid-19, Ground Staff, Layoff, Mental Health.

Abstract:

The COVID-19 pandemic forced numerous businesses to temporarily shut down and lay off their employees,

triggering profound mental health repercussions. Sudden job loss can result in anger, stress, anxiety, and

frustration, potentially leading to post-traumatic stress symptoms, substance abuse, and societal harm. This

study explores the impact of COVID-19-related layoffs on workers' mental health, aiming to

comprehensively assess their emotional experiences and coping strategies. The research employed qualitative

methods, including semi-structured interviews and document analysis, to collect and analyze data

thematically. Nine former aviation employees who had been laid off during the pandemic participated in the

study. The findings reveal that, despite the challenging circumstances, these individuals exhibited positive

mental health and psychological well-being following their job terminations. They predominantly employed

problem-focused coping mechanisms to navigate this crisis. What sets COVID-19-induced layoffs apart from

regular ones is the exceptional difficulty faced by these workers in securing new employment, given the

widespread industry disruptions. Ground staff at airports, with their specialized technical skills, encountered

even greater obstacles in finding alternative employment. This research underscores the unique challenges

and resilience exhibited by workers affected by pandemic-induced layoffs, shedding light on the importance

of mental health support and reemployment strategies in such extraordinary circumstances.

1 INTRODUCTION

The topic of mental health in the workplace has been

a subject of interest and discussion for a significant

period of time. In the past, the combination of

medicine, public health, and psychology was believed

to be a potential factor for preventing mental health

problems in the workplace (LaMontagne et al. 2014).

Job insecurity and conditions lead to diminished

productivity at work for workers with poor mental

health (Bubonya et al., 2016). Although many studies

have discussed mental health in the workplace, the

current Covid – 19 pandemic situations has made it

very different. A knowledge gap exists between

workers' mental health in normal and current

situations. The growing recognition of how the Covid-

19 pandemic affects workers' mental health in the

workplace has made research on this topic crucial.

One of the collateral damages of the Covid–19

pandemic is the progressive spread of stigma, as

evidenced by extensive research (Bruns et al., 2020;

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2179-5589

Logie & Turan, 2020). An employee who has been

sick, quarantined, and wants to return to work will

face problems during this time. The stigma toward the

workers who have experienced the Covid–19

increases the risk of psychopathology while

experiencing stigma in the workplace could lead to a

loss of productivity (Li, Yang, Zhang, Cheung,

Xiang, 2019). These situations highlight how work

conditions are crucial for workers' well-being during

the Covid–19 pandemic. The pandemic has altered

both the social and working environments in many

ways. Factors such as social distancing policies,

anxiety about the possibility of getting infected,

government policies about lockdown and isolation,

cessation of productive activity, decreasing income,

and fear of the future will somehow impact workers'

mental health. Therefore, the workplace is essential

for moderating or worsening employees' mental

health (Giorgi et al., 2020).

The COVID–19 pandemic has affected almost

every country worldwide. Consequently, it has far-

Restya, W. P. D. and Selian, S. N.

Occupational Health Implication of Covid-19 Layoffs on Airline Ground Staff: Study on Mental Health Effects.

DOI: 10.5220/0012901600004564

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Social Determinants of Health (ICSDH 2023), pages 115-123

ISBN: 978-989-758-727-6; ISSN: 2975-8297

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

115

reaching global economic and business consequences.

For example, the pandemic has caused the most

prominent global recession in history. Some of the

economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic

include a significant income decrease, transportation,

manufacturing, tourism, service disruptions, and,

finally, a rise in unemployment. The pandemic has

forced many industries to shut down and some are

permanently closed. One of the industries that was

affected the most by the pandemic was aviation. After

some countries announced travel bans and isolation

requirements, almost all airlines were forced to

severely limit their flights. This has led to a massive

layoff of airline employees (pilots, flight attendants,

groundling staff, etc.) in almost every country.

Corporate downsizing has resulted in job losses.

Many employees had experienced layoffs, while

others believed that they might soon lose their jobs.

Losing a job abruptly can be mentally disturbing and

potentially cause problems in workers’ mental health.

This opinion is strengthened through the research

findings of Sullivan and Von Watcher (2006) in

Mendolia (2009) that the death rate appears to have

increased significantly in the years after mass layoffs.

According to the Canadian Mental Health

Association, the impact of job loss is far greater than

just a matter of income loss. Beyond the direct

financial losses brought about by unemployment,

unemployment's often-overlooked yet more profound

impact during COVID-19 is on employees' mental

health (Fan & Nie et al., 2020).

Job loss sometimes leads to anger, stress, anxiety,

grief, and frustration (Rajkumar, 2020), which could

also lead to long-term post-traumatic stress

symptoms, such as alcoholism, drug addiction, and

suicide, which could harm individuals and society.

Given its enormous impact on individuals, it is

unsurprising that in 2015, the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs) included mental health

as a priority for global development. Ensuring healthy

lives and promoting well-being for everyone at any

level and age have made research on this topic

crucial. Some believe that mental health refers only to

depression, schizophrenia, and PTSD. Mental health

is an individual's overall condition (emotional,

psychological, and social well-being)

(mental.health.gov). Some studies have found a

profound negative correlation between COVID-19

and mental health; those existing studies only test the

general correlation between COVID-19 and mental

health, not giving enough attention to the specific

stressors from different perspectives and various

business sectors.

The airline industry, characterized by its unique

work environment, stringent regulations, and

unpredictable operational conditions, may present

distinctive factors that contribute to the impact of

layoffs on mental health. It is crucial to bridge this

gap by conducting empirical research in this specific

context. While previous research in the airline

industry has extensively examined the impact of

layoffs on the mental health of pilots (Olaganathan &

Amihan, 2021) and cabin crews (Görlich &

Stadelmann, 2020), there appears to be a significant

research gap in the investigation of layoffs’ effects on

the mental health of ground staff within the airline

industry. The ground staff, including mechanics,

engineers, and support personnel, play a critical role

in ensuring the safety and efficiency of airlines.

Nevertheless, their experiences and well-being during

layoffs have received limited attention in the existing

literature.

The ground staff in the airline industry have

distinct job responsibilities, work environments, and

career trajectories compared to pilots and flight

attendants. Thus, the effects of layoffs on the mental

health of ground staff may differ because of job-

specific factors, such as the nature of their work, level

of job security, and extent of interaction with

passengers and flight crews.

Hence, addressing this research gap in the

literature by conducting empirical studies on the

impact of layoffs on the mental health of ground staff

in the airline industry can enhance our understanding

of the unique challenges faced by this occupational

group. In addition, such research has the potential to

contribute to the development of evidence-based

interventions and strategies that support the well-

being of ground staff during periods of organizational

change and workforce reduction.

Therefore, this study explores the impact of

layoffs on the mental health of ground staff in the

airline industry. In addition, this research aims to

investigate the psychological consequences of such

layoffs on ground staff members, focusing on their

coping strategies and the responses that individuals

may exhibit following a layoff in the airline industry.

2 METHODS

This study was conducted on former Gapura Angkasa

outsourcing employees (Banda Aceh Branch Office,

Indonesia). Gapura has been one of the largest

ground-handling companies in Indonesia since 1998.

As an independent ground service provider, Gapura

offers services in passenger and baggage handling,

flight operations, hospitality, lounge, cargo, and

ICSDH 2023 - The International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

116

warehousing. The process was started by requesting

data from the HR department regarding the number of

terminated employees, then carefully selecting the

eligible participants, giving them informed consent (a

consent sheet was used to determine their willingness

to participate in this study), and finally interviewing

the HR about the criteria used in termination.

2.1 Research Design

The data were collected from terminated employees

of PT. Gapura Angkasa (one of the leading companies

in ground handling services and other business

activities that support the aviation business at the

airport) in the Banda Aceh branch office. This study

aims to describe a phenomenon involving rich data

collection from various sources to gain a deeper

understanding of individual participants, including

their perspectives, attitudes, and opinions.

2.2 Population and Samples

This observation employed a purposive sampling

methodology with two specified criteria: (1)

Terminated during the early COVID-19 pandemic in

Indonesia, which occurred between March and May

2020, and (2) Has worked for the airline's company

for at least ten years. These criteria were used to

choose the participants. The criteria listed above were

chosen based on various factors, including the fact

that not all employees were laid off as a result of the

covid 19 epidemic; some were laid off due to a lack

of commitment regardless of business regulations.

The period from March to May was chosen

considering that it was the moment when the airline

company had a massive termination owing to the

reduction in aircraft operational hours.

Considerations regarding work experience were

considered based on the statement of Estherina,

Puspitarini, and Rachmawati (2019), who mentioned

that employees with a ten-year service period are

considered to have a strong attachment and loyalty

toward the organization; hence, getting laid off must

be considered a betrayal and affect their mental

health. In March 2020, the company initiated the first

stage of employee dismissal, resulting in the

termination of twenty-three employees. This decision

was made for employees with less than two years of

work. Following the initial round of dismissals, the

company implemented a second stage in April 2020.

During this phase, an additional 17 employees were

allowed to go, bringing the total number of terminated

employees to 40.

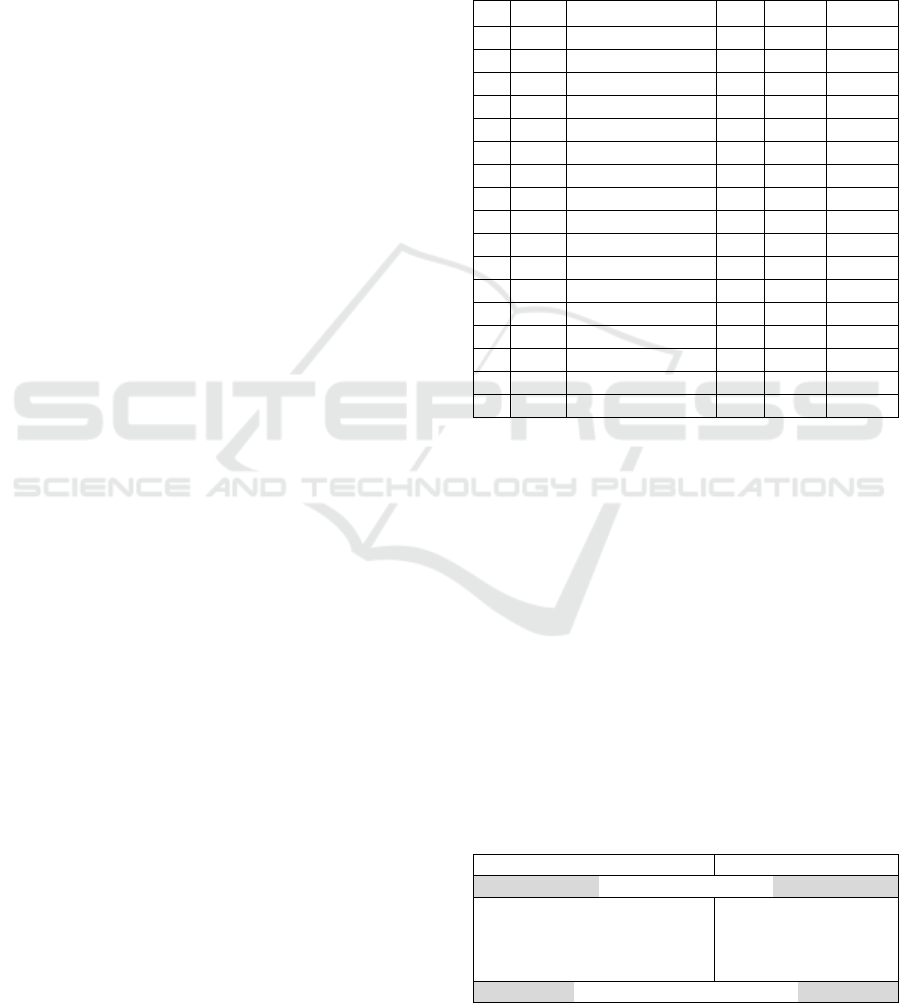

Therefore, this study focuses on employees who

were terminated in the second stage. The 17th

employees who were dismissed in the second stage

are listed in Table 2. According to the sample criteria

mentioned above, nine participants were eligible to

participate in this research, namely (by initials): ES,

UM, TRA, MJ, ZI, AS, TQ, AB, and IW.

Table 1: Samples of Terminated Employees (M = marriage,

S = Single).

Name Position Age Years Status

1 ES GSE Op 38 11+

M

2 UM Ramp Handling 30 10+

M

3 IB Loading Master 32 9+

M

4 FO Baggage Handling 26 6+

M

5 NA Baggage Handling 21 2+

S

6 TRA Baggage Handling 38 10+

M

7 MJ Baggage Handling 31 10+

M

8 RF Baggage Handling 24 2+

S

9 NZ Baggage Handling 21 2+

S

10 ZI Baggage Handling 40 12 +

M

11 IS Baggage Handling 30 8+

M

12 RJ AVSEC 26 5+

M

13 AS AVSEC 36 12+

M

14 TQ Greeting service 40 17+

M

15 AB Operation 38 14+

M

16 DM Ground handling 29 8+

S

17 IW Ground handling 35 11+

M

2.3 Data Collecting

The data were collected through semi-structured

interviews, non-participant observations, and

document studies, as elaborated below:

2.3.1 Semi-Structured Interview

The researcher used semi–structured interviews with

open–ended questions; therefore, the interviewer

could delve deeply into personal matters and

sometimes sensitive issues. The interview guide was

drawn based on six characteristics of mental health

from Jahoda (1958): attitude toward the self, personal

growth, integration, autonomy, an accurate perception

of reality, and environmental mastery.

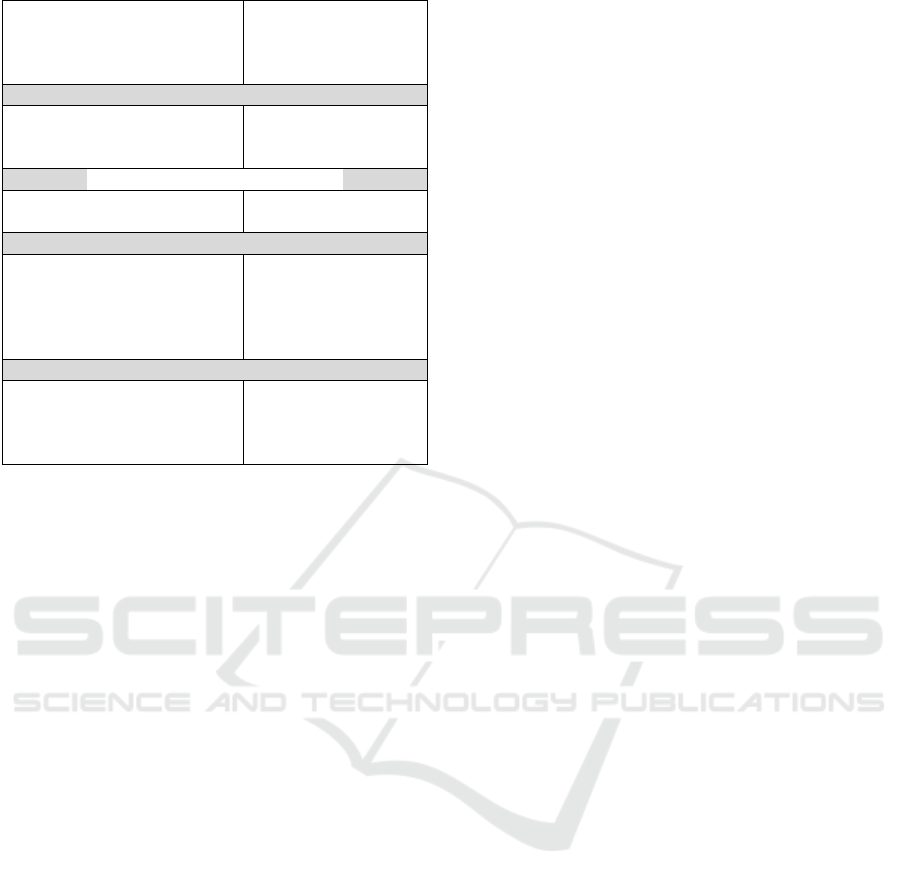

Table 2. Summary of Interview Guide.

Indicato

r

Questions Summar

y

Dimension: Autonomy

The individual can see himself

as an independent person and

at the same time able to work

with others cooperativel

y

How do you bounce

back after getting laid

off?

Dimension: Personal Growth

Occupational Health Implication of Covid-19 Layoffs on Airline Ground Staff: Study on Mental Health Effects

117

Desire to use all the abilities to

achieve something, & having

a reasonable life goal, making

a certain effort to achieve it

What do you think

about equipping

yourself with new

skills?

Dimension: Perceive

d

Self Efficacy

The thoughts, feelings, and

ideas that a person has about

himself

How satisfied are you

with your life these

days?

Positive Attitude Towar

d

the Self

Able to evaluate or assess their

own ability, and capacity

How do you treat

yourself lately?

Environmental Mastery

Facing life’s uncertainty with

positive affirmation, an

individual’s feeling toward the

family, work, social life

Do you think you

could always rely on

your family or friends

in case you need

support?

Perception of Realit

y

Ability to learn & interpret

external phenomena in

relation to the norms and have

a realistic view of the world

Have you felt isolated

lately?

2.3.2 Non – Participant Observation

Observations are usually used to gain insight into a

specific setting and actual behavior (Hak, 2007).

Observations can be classified into two types:

participant observation and non-participant

observation. The type of observation used in this

research is a non-participant observation, which

means that the observer is not part of the observation

and tries not to influence the setting by their presence.

During the observation, the observer took notes on

everything that was significantly shown by the

participants, for example, their expression when they

talked about the layoff, their emotions, their gestures,

etc.

2.3.3 Document Analysis

This study analyzed documents through non–

personal documents, such as company policies,

regardless of termination procedures. To manage the

validity and reliability of the data research, method

triangulation was also used to assess the consistency

of our findings by combining multiple data sources.

To gain a better understanding of the phenomenon,

various approaches were taken to analyze the data

from different perspectives.

2.4 Data Analysis

To assess the mental health of workers who have been

terminated, a thematic analysis was conducted.

Thematic analysis is a qualitative method that is

usually applied to a set of texts, such as interview

transcripts. We closely examined the data to identify

the themes, ideas, and patterns of meaning that

emerged repeatedly. Analyzing data through thematic

analysis consisted of six steps: familiarization,

coding, generating themes, reviewing themes,

defining and naming themes, and writing the

conclusion or result.

3 RESULTS

According to the collected data, the company

terminated 40 employees in early 2020. This

termination of employment was carried out in two

stages: in the first stage, the company laid off 23

employees, while in the second stage, another 17

employees were dismissed. The participants admitted

that the termination of employment was carried out

by telephone and WhatsApp applications due to

social distancing. This action made them feel

unappreciated and thought they could be easily

replaced. Even though, in the end, the company called

back to provide an official letter, the feeling

remained.

“…. One afternoon, I was called and informed

that I had been temporarily laid off. I was very shocked

and the fact that they gave me such important news on

the phone made me feel disrespected… You know… I

mean…I have been working for the company for 10

years or more now. Didn’t I at least deserve a better

way?” (Verbatim of subject UM – line 0017)

During the pandemic, employer considerations for

employee termination included factors such as the

current situation, flight operating hours, employee

performance test results, and period of employment.

Researchers have pointed out that layoffs during the

pandemic were different from those in regular times

in several significant ways. First, employees were

often terminated with short notice, leaving little time

to prepare or seek alternative options. Second, there

was a possibility that they might need to receive

severance pay, which adds to the financial burden of

losing their jobs.

Finally, finding new employment opportunities

has become increasingly challenging owing to the

widespread impact of the pandemic on various

industries. These findings highlight the distinct

challenges that employees encounter when going

through layoffs caused by the pandemic. Additionally,

the complexity of their job roles and advanced

technical abilities pose a challenge in securing

alternative employment opportunities.

ICSDH 2023 - The International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

118

3.1 Terminated Worker’s Mental

Health

As previously stated, there were nine eligible

participants who were willing to partake in this

research. Once the participants were presented with

the informed consent form and had their rights and

responsibilities explained to them for the research, a

semi-structured interview was conducted. The

researcher compiled an interview guide based on

Jahoda’s (1958) theory. A summary of the interview

guidelines is provided in Table 3. Overall, the results

showed that participants' mental health was positive.

This can be seen through the participant's verbatim

transcript, which showed their ability to cope with

unpleasant situations such as termination. Even the

individuals had anticipated that a situation like this

would arise, given the current state of the Covid-19

pandemic. Nevertheless, they were taken aback upon

hearing about the layoff for the first time.

Furthermore, it was observed that the research

participants were able to quickly adjust to their

situations and maintain a positive mindset. They were

able to gain valuable insights, make informed

decisions, and reorganize their lives accordingly. It is

worth noting that five of the subjects who were laid

off were able to secure new employment within 1-1.5

months. This serves as evidence that their perceived

self-efficacy, positive self-image, and realistic

perception of reality were strong, as suggested by the

theory.

It has been found that out of the six dimensions of

mental health, most of the subjects scored low in the

category of personal growth. The subjects

acknowledged that they did not actively seek out

opportunities to acquire new skills or knowledge

because they were more focused on finding a new job

as quickly as possible. They believed that improving

themselves with specific skills was a waste of time. A

more in-depth discussion regarding the six indicators

of mental health that were evaluated will be provided

through the following points: autonomy, personal

growth, perceived self-efficacy, positive attitude

towards oneself, perception of reality, and

environmental mastery.

3.1.1 Autonomy

Many participants who have been laid off could take

control of their lives. This is evident in their ability to

independently plan and reorganize their lives after

experiencing job loss. As expressed by one subject:

"During the first month, I did not want to think about

work at all. I just wanted to enjoy my life. I had not

taken time off in 10 years, so I decided to relax. But

now, after a month has passed, I'm focused on finding

a new job or starting a new venture." (From the

transcript of Subject TRA - Line 0081)

Regarding the other subjects, AB and IW reported

that it took them only one week to recover and refocus

on their life goals. AB stated: "All I wanted at the time

was another job, regardless of whether I liked it or

not. I had to support my family, so finding a new job

was crucial. I even considered taking odd jobs as long

as they were halal, as the priority was to secure a new

job immediately" (verbatim, line 0008).

Differences in gender and marital status may

influence one's perspective. For instance, TRA,

whose financial stability is supported by her husband,

feels less urgency in seeking a new job and can take

her time deciding when to return to work. However,

for the other subjects, who are the heads of their

households with children and a spouse to support,

immediately setting new life goals after being laid off

is imperative.

3.1.2 Personal Growth

Among the nine subjects, only MJ believed that

acquiring new skills would improve his career. MJ

stated that: “Yes, I am considering taking some

training either from the government or independently.

I am not good in a foreign language; thus, I might

consider learning the English language for instance”

(Verbatim Subject MJ – line 0087)

Subject ES believes that they don't require any

particular training to enhance their skills for

securing a better job. "I didn't undergo any training.

I don't think it's essential. Moreover, I quickly

landed a new job, so I didn't feel the need for it"

(verbatim Subject ES - line 0093).

UM, the subject, believed that his ten years of

experience at Gapura Angkasa company was

sufficient for obtaining a new job. Therefore, he did

not see the need to attend any training sessions to

acquire additional skills. "I didn't participate in any

particular training. I have over 10 years of experience

from my previous job, so I felt that was sufficient. It's

just a shame that I was deemed too old to participate

in any training." (Exact quote from UM subject, line

0077)

3.1.3 Perceived Self Efficacy

In this study, nine individuals initially experienced

shock, sadness, and feelings of rejection upon

learning that their company had laid them off. They

had never considered the possibility of being laid off

before, as they had been employed by the company

Occupational Health Implication of Covid-19 Layoffs on Airline Ground Staff: Study on Mental Health Effects

119

for an average of over ten years, as reported by three

of the participants.

One participant stated, "I was extremely

surprised. I did not want to believe it at first. When

I was told

during the day, I was confused. But at

night, I felt very

sad and had trouble sleeping."

(Direct quote from Subject TRA line 0063)

"At the time, I believed that the layoff was only

intended for new employees. I couldn't understand

why I was on the list too, given that I had been with

the company for over 10 years." (Direct quote from

TRA line 0059)

“We were all devastated at that time,

particularly since it occurred so near to Eid Idul

Fitri. (Direct quote from Subject TQ, line 0068).”

"I didn't anticipate getting laid off although I

knew that the pandemic would greatly reduce

flights and potentially affect my job, I didn't expect

to be let go so quickly." (Original quote - AS line

0060)”

That emotion, however, did not stay long. In general,

the individuals in this study understood the

company's circumstances. The subjects confessed

that it only took them a moment to comprehend the

information of the layoff and immediately accepted

the truth, although they were dissatisfied that they

would not receive any severance compensation as a

result of the layoff.

"We understand the situation; it's not like the

company voluntarily laid us off; it was due to the

pandemic, and we truly understand that!" The only

thing that makes us really upset with the company is

that it did not compensate us when we were let off.

All allowances are immediately terminated. My

BPJS has been canceled, and all of my

authorizations have been removed." (Original quote

– ZI line 00072)

3.1.4 Positivity Towards Oneself

Concerning positive relationships with themselves

and others, the interviewees confessed that after being

laid off, they regained self-love and self-worth,

becoming more appreciative of jobs and family.

Subjects reported that the presence of their closest

friends and family helped them cope with the layoff

scenario throughout the epidemic. These subjects felt

completely supported by their families, allowing

them to embrace themselves without feeling

overwhelmed. The family's reaction to the layoff has

been mostly positive, with direct support such as

assisting with a job search or simply providing

incentives. According to the research subject, this

type of deed has become a good reinforcement for

them to proceed forward.

"When the company laid me off, I began to fully love

myself and my family." Being laid off after more

than ten years with the company made me realize

that the company did not need me as much as I

needed them. They might easily replace me with

someone else. As a result, I began to love myself

more, to do things that I enjoy, and to abandon

activities that are detrimental to myself and my

family." (Subject UM line 0081 in Verbatim)

3.1.5 Environmental Expertise

Almost identical to the explanation above, the

participants have been able to master the

environment, take advantage of chances, and regulate

the environment according to their needs. Subject

AB, for example, was instantly looking for a new job

opportunity in order to meet his daily basic demands.

The individual eagerly explores every possibility, for

example, by contacting close friends or family to

inquire about career chances.

"It's extremely difficult to find a new job because

I no longer meet the age requirement." People are

terrified when they learn about my 10 years of job

experience; they are concerned about a proper

salary for someone at my level. Furthermore, my

extensive technical background in the aircraft

industry has made it difficult for me to find a job that

matches my former skills." (Line 0089 of Verbatim

Subject II - AB)

Subject TRA, in contrast to the previous subject, does

not rely on family or close connections to get new

employment. Instead, the subject TRA likes to

leverage the complexity of modern technology to

identify existing career chances.

"I'm looking for a new job on my own."

Everything is digital nowadays, so it should be

simple, right? Instagram provided me with some job

posting information. I'm not the picky sort, so I

applied to any firm and position that was available

because I did not mind becoming a waiter, a cashier,

or anything else. I will just take whatever

opportunity comes my way! (Line 0085 of Verbatim

Subject 1- TRA)

3.1.6 A Realistic Perception of Reality

In terms of reality perception, the nine research

subjects have acknowledged that they have been laid

off by the company. They are, however, ready to go

on with their lives and are confident that they will

reach their objectives shortly. They feel that their past

ICSDH 2023 - The International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

120

experiences will give worth to their lives in the future.

The subject TRA believes that her experience as a

front liner at PT Gapura Angkasa is comparable to her

new position as a cashier at PT MT, where both

occupations require similar customer service skills.

3.2 Dealing with Job Loss

The three subjects' emotional stages of processing job

loss are quite comparable. Shock, disappointment,

and denial were followed by an attempt to make peace

with oneself (bargaining), and finally coping with the

situation (acceptance). See Figure 1 for further

information.

Shock

Disappointment

Denial

Bargaining

ACCEPTANCE

Figure 1: Stage of Procession Job Loss.

To bolster this point, psychiatrists point out that

losing a job is sometimes equated with the sadness of

losing a loved one. Any stage of grieving can be

included in the emotional trajectory, which ranges

from shock and denial to rage and bargaining, and

finally to acceptance and hope. As stated by the

subject:

"I was stunned at the time. I'm unable to accept

the fact that I no longer have a job. Later that night,

I felt both sad and angry... (full transcript of Subject

IM Line 0063)

Furthermore, because the subjects are all married, the

sudden job loss prompted them to return to work as

quickly as possible in order to meet their

commitments to their families. It serves as a

tremendous motivator for all three topics.

3.3 Coping Techniques

According to Lazarus and Folkman (1966), coping

methods can be divided into two types: problem-

focused coping and emotion-focused coping.

Problem-focused coping entails dealing with stress

while actively addressing the issue. Emotion-focused

coping, on the other hand, is associated with efforts to

change or minimize stress-related negative feelings.

To cope with job loss, all three subjects in this

study

employed problem-focused coping mechanisms,

such

as immediately seeking new possibilities even if

the job opportunities were radically different from

past work experience. To summarize, families are

regarded as the finest support mechanism for the three

subjects dealing with layoffs during the COVID-19

pandemic. Acceptance from a loved one can be quite

beneficial in getting through difficult circumstances.

Meanwhile, in order to protect workers' mental

health, the corporation planning the mass dismissal

should examine whether it is necessary, and if so,

please do so with compassion (Knight, 2020).

4 DISCUSSIONS

The findings revealed that the three participants'

mental health was in good shape after being laid off

during the pandemic. It is possible because all of the

subjects chosen for this study were employees of the

airline. As we all know, the airline industry has

dramatically cut operation hours due to government

rules, independent of travel constraints. As a result,

many other industries in the aviation industry have

temporarily laid off some employees. Workers have

predicted that they will be laid off shortly as a result

of this circumstance.

As a result, the research participants braced

themselves for the worst-case scenario of being laid

off by the corporation during the COVID-19

epidemic. Workers were more inclined to take

preventive action after acknowledging the

uncomfortable situation, as predicted. Workers were

more inclined to take preventive action after

acknowledging the uncomfortable circumstance, as

predicted. embracing reality is not always easy, but

according to the research subjects, embracing the

current circumstance will help them overcome the

problem and lead to higher self-acceptance and a

brighter future. They think that, even if the situation is

dire, the first step toward improvement is admitting it

for what it is.

Even if the layoff occurred during the epidemic, it

had no significant impact on their mental health

stability. Many psychological research has found that

self-love, self-compassion, and self-acceptance are

essential for mental health and well-being (Germer &

Neff, 2013). According to research, having more self-

compassion and self-acceptance increases resilience

in the face of adversity, allowing people to recover

more rapidly from unpleasant experiences (Germer &

Neff, 2013).

It also assists people in dealing with failure or

Occupational Health Implication of Covid-19 Layoffs on Airline Ground Staff: Study on Mental Health Effects

121

embarrassment (Ferrari et al., 2018). Almost identical

to the findings of this study, other studies have found

that thankfulness mediates the association between

layoffs, salary reductions, and employee mental

health. Gratitude, defined as a strong sense of

appreciation for something or a sense of being

grateful, can be used to promote employee mental

health (Parianti, Sofianti, Rosid, 2020).

Another line of research, however, reveals that

work uncertainty, wage cuts, layoffs, and reduced

benefits all contribute to job insecurity and, in the

long run, negatively affect mental health. These and

additional concerns may occur or worsen as a result

of COVID-19 (Lund et al., 2018). This statement is

supported by research on "Unemployment and

Mental Health" conducted by Wilson and Finch

(2021), who stated that rates of both unemployment

and poor mental health have increased during the

pandemic, as statistics show that in January 2021,

43% of unemployed people and 34% of people on

furlough had poor mental health. This study shows

that furloughing has offered some mental health

protection.

Workers with pre-existing mental health

problems, according to Yao et al. (2020), are

generally less able to manage because of the many

pressures caused by the COVID-19 epidemic.

Additionally, workers who previously had a mental

health illness may see their condition deteriorate. As

a result, new employment initiatives should be

created to mitigate the impact on workers' mental

health and well-being. It is also vital to provide

intensive support that provides stability for the laid-off

employee.

In general, after experiencing layoffs, all

participants

undergo some changes in themselves; this is

the result of a combination of positive and bad

feelings

from the circumstances they encounter. As can be

observed from the numerous discussions on mental

health indicators above, the three research subjects

have good sentiments about the events, therefore

layoffs due to the COVID-19 pandemic did not

immediately cause their mental health to deteriorate.

Individuals do not need to feel good all the time

to have

sustainable mental health; on the contrary,

feeling bad

emotions from life is a natural part of

existence; what is required is the ability to manage

these negative emotions, which is essential for

individuals' long-term well-being.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the findings of this study imply that

workers who were laid off during the pandemic had

excellent mental health outcomes that were impacted

by a variety of factors. Most of the participants had

anticipated the potential of being laid off, which

helped them cope with the first shock and navigate

the difficult situation. They demonstrated resilience

by restructuring their lives, especially their

occupations, and demonstrating their adaptability.

The findings also confirmed that individuals

maintained a positive self-perception and an accurate

knowledge of reality.

Notably, critical contrasts were made between

layoffs during a pandemic and those that occur under

normal conditions. To begin with, pandemic-related

layoffs frequently occurred on short notice, giving

employees little time to prepare.

Furthermore, as a result of the pandemic's poor

circumstances, afflicted persons frequently faced

obstacles such as a lack of severance pay and limited

career options. Participants went through a variety of

emotional phases when dealing with job loss,

including shock, disappointment, denial, bargaining,

and acceptance. The individuals' coping mechanisms

were predominantly problem-focused coping, as

evidenced by a proactive attitude to addressing their

issues.

REFERENCES

Bubonya, M, Cobb, C, Deborah A, Wooden, M. 2016.

Mental Health and Productivity at Work: Does What You

Do Matter. IZA Discussion Papers, No. 9879, Institute

for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn

Bruns D.P., Kraguljac N.V., Bruns T.R. COVID-19. 2020.

Facts, Cultural Considerations, and Risk of

Stigmatization. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020;31:326– 332.

doi 10.1177/1043659620917724. [PMC free article

Cuijpers, P.; Smit, F. 2002. Excess Mortality in Depression:

A Meta-analysis of Community Studies. J. Affect.

Disord. 2002, 72, 227–236. [CrossRef]

Ferrari, M. et al. 2020. Self-Compassion Moderates the

Perfectionism and Depression link in Both Adolescence

and Adulthood. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/articl

e?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0192022

Fawler, D. 2020. Unemployment during Coronavirus: The

psychology of Job Loss. Available at: https://

www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200327-unemploy

ment-during-coronavirus-the- psychology-of-job-loss]

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192022

Germer, C.K & Neff, K.D. 2013. Self–Compassion in

Clinical Practice. Wiley Periodical Inc. Journal Clinical

Psychology 69: 1-12, 2013

Giorgi, G et al. 2020. Covid-19 Related Mental Health

Effects in the Workplace: ANarative Review.

International Journal of Environment. Public Health

ICSDH 2023 - The International Conference on Social Determinants of Health

122

2020, 17(21), 7857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph172

17857

Görlich, Y., & Stadelmann, D. 2020. Mental Health of

Flying Cabin Crews: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers

in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020

.581496

Hak, T. 2007. Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief

onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief

onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische

praktijk. [Observation methods in qualitative research]

(pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Jahoda, M. 1958. Current Concepts of Positive Mental

Health. New York: doi:10.1037/11258-000

Kashdan, H & Rotternberg, J. 2010. Psychological

Flexibility as a Fundamental Aspect of Health. Clinical

Psychology Rev. 30 (7): 865 – 878.

Kenton, W. 2019. Layoff. Available at: https://www.

investopedia.com/terms/l/layoff.asp

Huber, M. Knottnerus, J.A. Green, L, & et al. How Should

We Define Health? Available at: [BMJ 2011;

343:d1463–6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmj.d4163doi:10.1136/b mj.d4163

Kruijshaar, M.E.; Hoeymans, N.; Bijl, R.V.; Spijker, J.;

Essink-Bot, M.L. Levels of Disability in Major

Depression: Findings from the Netherlands Mental

Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). J.

Affect. Disord. 2003, 77, 53–64. [CrossRef]

Knight, R. 2020. Layoff during Covid -19: How to manage

coronavirus layoff with compassion. Available at:

https://hbr.org/2020/04/how-to-manage-coronavirus-

layoffs-with-compassion

Legg, J.T. 2020. What is Mental Health? Available at:

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/15454

Lazarus, R S., & Folkman, S. 1966. Stress, Appraisal,

and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Maddi, Salvatore

LaMontagne, A.D et al. 2014. Workplace Mental Health:

Developing an Integrated Intervention Approach. BMC

Psychiatry. 2014;14: 131. Doi:10.1186/1471- 244X-14-

13

Logie C. H., Turan J.M. 2020. How Do We Balance

Tensions Between COVID-19 Public Health Responses

and Stigma Mitigation? Learning from HIV Research.

AIDS Behav. 2020; 24:2003–2006. doi:

10.1007/s10461-020-02856-8

Li W., Yang Y., Ng C.H., Zhang L., Zhang Q., Cheung T.,

Xiang Y.-T. 2019. Global imperative to combat the

stigma associated with the coronavirus disease 2019

pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–2. doi:

10.1017/S0033291720001993

Lund, C. et al. 2018. Social Determinants of Mental

Disorders and The Sustainable Development Goals: A

Systematic Review of Reviews. The Lancet Psychiatry,

5(4) (2018), 357 – 369

Moore, T.H.M.; Kapur, N.; Hawton, K.; Richards, A.;

Metcalfe, C.; Gunnell, D. 2016. Interventions to reduce

the impact of unemployment and economic hardship on

mental health in the general population: A systematic

review. Psychol. Med. 2016, 47, 1062–1084.

[CrossRef] [PubMed] Sustainability 2020, 12, 7763 22

of 23 5

Olaganathan, R & Amihan, R. 2021. Impact of COVID-19

on Pilot Proficiency – A Risk Analysis. Global Journal

of Engineering and Technology Advances. 6. 001-013.

10.30574/gjeta.2021.6.3.0023.

Parianti, E; Sofianti, N & Rosid, A. 2020. Layoff and The

Mental Health of Remaining Workers in Pandemic

Covid -19. International Sustainable Competitiveness

Advantage

Punch, K. F. 2013. Introduction to social research:

Quantitative and qualitative approaches. London: Sage

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. 2003. Evaluation of

qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing,

6(2), 36–40

Reynolds, D.L.; Garay, J.R.; Deamond, S.L.; Moran, M.K.;

Gold, W.; Styra, R. 2008.Understanding, Compliance

and Psychological Impact of the SARS Quarantine

Experience. Epidemiol. Infect. 2008, 136, 997–1007.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

Rajkumar, R.P. 2020. Covid-19 And Mental Health: A

Review Of Existing Literature. 2020. Asian Journal

Psychiatry

Suls, J.; Bunde, J.2005. Anger, Anxiety, and Depression as

Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease. Psychol. Bull.

2005, 131, 260–300. [CrossRef]

Stunkard, A. J.; Faith, M. S.; Allison, K.C. (1969).

Depression and Obesity. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003, 54,

330–337. [CrossRef]

Yao, H et al. 2020. Patients with Mental Health Disorders

in The Covid – 19 Epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry 7

(4), E21

Wilson, H; & Finch, D. 2021. Unemployment and Mental

Health: Why Both Require Action for Covid -19

Recovery. The Health Foundation https://www.

mentalhealth.gov/basics/what-is-mental-health

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-

health-strengthening-our-response

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavi

rus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/corona

virus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it- transmitted

Occupational Health Implication of Covid-19 Layoffs on Airline Ground Staff: Study on Mental Health Effects

123