In Nature's Embrace: Abdulla Qahhor's Visionary Works

Isayeva Shoira

Tashkent State University of Uzbek Language and Literature, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Keywords: Environment, Environmental Education, Natural Scenery, Poetics, Horizon.

Abstract: This article highlights the significance of artistic works in shaping students' affinity for nature, ecological

awareness, and appreciation of natural landscapes. Through an analysis of Abdullah Kahhor's works, the text

demonstrates how descriptions of the environment and expressions of love for the earth contribute to shaping

a profound ecological culture. Qahhor's art exemplifies a commitment to environmental protection, with vivid

depictions fostering a deeper connection between individuals and the natural world. The exploration of these

themes in his works serves as a compelling testament to the potential of art in instilling a sense of

responsibility and admiration for nature among students.

1 INTRODUCTION

Abdulla Qahhor is a real writer, a talented storyteller

who has a place in life and art, and who won the hearts

of people with his unique talent and sharp pen. He is

one of the most influential figures in Uzbek literature

with his inexhaustible works, unique artistic style,

and ability to express many meanings in a few words.

In his works, the author was able to reveal the truth of

life, sometimes with irony, sometimes with laughter,

and it was not for nothing that he was recognized as

the “King of Fairy Tales.” In recent years, a lot of

creative work has been done to reveal the creative

path of Abdulla Qahhor and the essence of his works.

In particular, Naim Karimov, in his work

"Landscapes of 20th-century Literature," gave

information about the life and work of A. Qahhor,

which we do not know. Literary critic Rahmon

Kochkor prepared the author's program

"Astonishment" - Koshjanov M (1984), dedicated to

the life of the writer. Also, young artists such as

Umarali Normatov, Ibrahim Hakkul, and Markhabo

Kuchkarova studied the life and work of Abdulla

Kakhkhor. The reason for the interest in the

unparalleled creativity and life of the author is his

courage. What courage can you say?! In the works of

Abdulla Qahhor, not only is the image of love for

humanity, environment, and nature revived.

We all know that the author's work was carried

out under the pressure of an authoritarian regime that

opposed any news. Abdulla Qahhor was not afraid to

reveal the plight of the oppressed people in his works

at a time when the so-called Soviet poets of that time

were singers of truth and persecuted writers. He

sought to bring people out of spiritual poverty and

depravity and warn them of the dark days of

colonialism. As the author put it: "Better a poor horse

than no horse" - Sharafiddinov O. (1988). This bitter

truth is the truth of the past. The writer managed to

convey this to his contemporaries and us, generations,

not simply, but through his satirical and humorous

works. The condition of our people, the oppression to

which our country is subjected, corruption, and

deception of the government, whose intentions boil

down only to robbing the people, are demonstrated in

their masterpieces. In a word, Abdulla Qahhor is a

translator of the national language.

2 ANALYSIS

Figure 1: Literary Insight: Navigating Analysis with Core

Principles.

Firstly, let's explore the narrative of "The Thief." In

this story, we bear witness to the challenges of the era

in which the author lived and worked, highlighting

Shoira, I.

In Nature’s Embrace: Abdulla Qahhor’s Visionary Works.

DOI: 10.5220/0012952600003882

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies (PAMIR-2 2023), pages 1085-1088

ISBN: 978-989-758-723-8

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

1085

the spiritual destitution of individuals manipulated by

colonialists. The burglary of Cain's house, the

protagonist, serves as a portrayal of the actions of

dishonest, corrupt officials. This is further

substantiated by the story's epigraph, "Death of a

Horse, Dog Feast," where Cain's grandfather's cow is

abducted, revealing the financial struggles of the

people of that time.

The narrative unfolds with Cain robbing his

grandfather by making fifty unfulfilled promises.

Amir's speech characterizes the officials of the time

as self-centered and indifferent to the people's plight.

Throughout the story, Cain is repeatedly robbed,

illustrating that the true thief is the tyrannical

government, deceiving the populace. The

culmination of the tale sees the bull's father-in-law

giving him two oxen, signifying ongoing

exploitation. Cain hints at a "small" condition,

implying he remains subject to further exploitation.

Abdulla Qahhor's stories unequivocally condemn

the past. "Horror" vividly portrays the atmosphere of

the time, highlighting the spiritual backwardness and

tragedy of the era. The epigraph, "Women who do not

know the day when women saw him in the past do not

believe what they say," reflects the lack of rights for

women in that period. The protagonist, Unsin, faces

the nightmare of being given to an old man in

exchange for her father's debts, reflecting the

financial difficulties endured during the Soviet era.

Living in the dodho house becomes a torment for

Unsin, who escapes to the cemetery for solace. This

desperate act illustrates the horrifying environment

she seeks to flee. Despite achieving her freedom, the

story takes an unexpected turn as Unshin's spirit is

liberated, adding a haunting layer to the narrative.

In the analysis of Qahhor's story "The Patient,"

the narrative exposes the invisible shortcomings of a

sick woman mirrored in society. The author skillfully

uses storytelling to contemplate societal issues,

depicting the suffering of the people from poverty.

The story emphasizes the struggles of securing a loan

for medical treatment and critiques the idea of a

hospital with "money depicting a white Podsha." -

Abdullah Qahhor (1987).

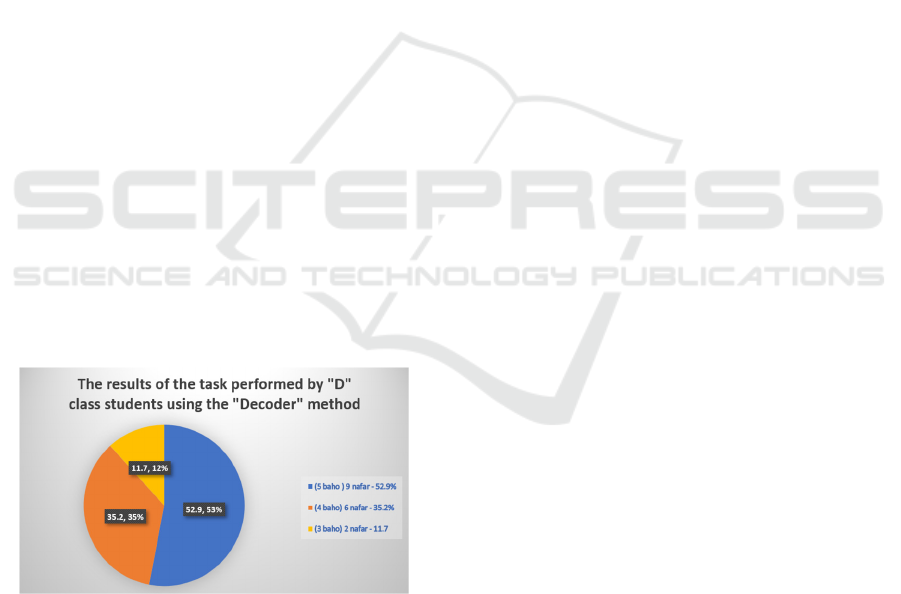

Figure 2: The criteria of Art.

In an interview with Mushtum magazine, Abdulla

Qahhor said: "He has destroyed the art, the most

important educational tool." It makes every writer

feel proud and proud. Because it's not for nothing, it's

up to each writer to understand. Therefore, the writer

cannot explain his feelings in any way. He tries to

explain the sincere words of his heart to young

readers and all his fans through his works. This

requires great courage, contentment, and patience

from the writer. Abdulla Qahhor was such a brave,

contented and, of course, patient man.

In today's process of globalization and

integration, there is no need to explain how important

it is for each nation to know its past, the heritage of

its ancestors, and the history of the formation of the

nation. At the same time, the works of art that play an

important role in shaping the worldview of today's

man, in particular, the works that reflect the way of

life, thoughts, and aspirations of our people in a

particular period, are especially invaluable. By

reading and studying such works, we can better

understand the spiritual values and changes in the

spiritual worldview of our people. From this point of

view, if we talk about the works of Abdulla Qahhor,

a writer who created his own great school of literature

in the literature of the twentieth century, we will be

able to put forward a very pure truth. Abdulla

Qahhor’s stories, first and foremost, amaze with their

sincerity and persuasive power. Everything in the

author's image is a life event, an event that happened,

a part of real life, an episode; most of the stories are

based on real life, they are taken from the events that

the writer saw and heard in his life, from the lives of

acquaintances. But they are not exactly a copy of life.

"If writing was about copying from life, there would

be no easier job in the world," he said. Copying from

life is like copying from a book. Copies will remain.

You can't expect originality from such things.

Originality comes from experiencing the realities of

life, feeling them, absorbing what you are thinking,

and expressing your desires.

Abdulla Qahhor was also an effective translator.

He skillfully translated the centuries of Pushkin,

Tolstoy, Gogol, and Chekhov into Uzbek. In

particular, Chekhov translated his works with special

interest and experience. Of course, the writer's

services and hard work paid off. In 1966 he was

awarded the Hamza State Prize, in 1967 the People's

Writer of Uzbekistan, and in 2000 the Order of Merit.

Abdulla Qahhor is named after several streets,

schools, and collective farms in Tashkent and

Kokand, as well as houses of culture and the

Republican Satire Theater. In 1987, the Abdulla

Qahhor House-Museum was opened in Tashkent. His

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

1086

works have been translated into Russian, Kazakh,

Ukrainian, Belarusian, Kyrgyz, Karakalpak, and

Tajik languages. Some of his stories have been

published in English, German, French, Czech, Polish,

Bulgarian, Romanian, Arabic, Hindi, and

Vietnamese.

The fate of literature is inextricably linked with

the fate of the country and the nation. The spirit of the

nation, in all its complexity and contradictions, must

first be reflected in literature. Literature also finds an

ointment for the nation's heartaches. When the

people's pleasure in life diminishes, their enthusiasm

diminishes. When spiritual zeal decreases, thought

and initiative ceases. Literature is primarily

responsible for this. As Abdulla Qahhor put it,

"Literature is stronger than the atom."

On the eve of independence, and for some time

after that, some were a little skeptical and skeptical of

the works of such great writers as Oafur Ulum,

Oybek, and Abdulla Qahhor. Their creative

achievements, those who did not take into account the

hard work and suffering of the national literature to

become real literature, began to emerge. However, as

a result of such a wrong attitude, our literature did not

develop. On the contrary, the ranks of those who

could not write two sentences, who understood the

essence of creation superficially, and who wrote on

paper were growing. The value of literature in the

eyes of students and the reputation of the writer has

diminished. Would this be the case if Abdulla Qahhor

or Oybek looked at art learned from their art school

and drew conclusions from their experiences? I think

the situation would be relatively different.

Figure 3: The result of the Text Analysis.

Ozod Sharofiddinov reminisces about the writer

Abdulla Qahhor, recalling that he himself set a good

example of adherence to these principles in his

critical work. His articles in the central press,

particularly in the "Literaturnaya Gazeta," as well as

in our country, his speeches at literary conferences,

and his interactions with colleagues are clear

evidence of this. The author's articles in the press,

which later appeared in his collections, and the points

that stirred the audience at large literary gatherings

are well-known. For eight years, I have met Abdulla,

sometimes in private, in the city yard or in the

Dormon garden, often with Said Ahmad, Askad

Mukhtor, Odil Yakubov, Pirimkul Kadyrov,

Matyokub Kushjanov, Ozod Sharafiddinov, as well

as, when recalling some exemplary critical remarks

and comments made by critics of the same age and

younger as me - writers Olmas Umarbekov, Erkin

Vahidov, Abdulla Aripov, Utkir Hoshimov, Shukur

Kholmirzaev, Uchkun Nazarov, Norboy

Khudoiberganov, I always sincerely acknowledge the

high faith, honesty, and principledness of this man.

Fiction Publishing House is preparing a monograph

on Abdulla Qahhor's work to mark his 60th birthday.

The monograph was written by critic Matyokub

Kushjanov. Matyoqub invited me to write a story part

of the book. The book was originally called "The

Master of Confirmation and Denial." When

Matyoqub asked Qahhor for his opinion on the title of

the book, he did not like it. Then we decided to call

the book "The Secrets of Mastery." Hearing this,

Abdulla Qahhor said, “It is a good name, but such a

name is appropriate for books about Navoi, Tolstoy,

and Chekhov. Their work is full of secrets of

mastery."I have a secret," he said. No other name was

found; the book was published under the title "Secrets

of Mastery," but the author did not see it. If he were

alive, wouldn't he be offended if the book came out

under that name? I do not know whether Abdulla

Qahhor was directly involved in the theory of

literature, but I have heard many of his eloquent

statements about literature, the nature of criticism, its

laws, and its principles. Speaking of the creative

method, he once said, “Recently, writers from Poland

have asked me what I think about it. I told them, “The

creative method is not a set of street rules. It's a

beacon that illuminates the path to the truth for the

writer," I replied. In the last years of his life, Abdulla

Qahhor regularly participated in youth seminars led

by the poet Mirtemir of the Writers' Union. But no

matter how hard they tried, he would not speak at

these meetings. When I asked why, he said, “I want

to write about the lives of young people. Young artists

know the language, the mood of today's youth better

than we do; they feel it.

Asked in connection with the novel "Sarob" in

1965, the writer said, "Criticism has so far sought a

clear policy from 'Sarob.' There is no one in the novel

who can hear the suffering of the people.” The

author's remorseful words did not give me peace for

a long time and prompted me to write something that

In Nature’s Embrace: Abdulla Qahhor’s Visionary Works

1087

would shed light on the suffering of the characters of

"Sarob." I tried to make some comments on this in the

1990 article "Lessons of Life" published in the "Star

of the East." However, in an article entitled

"Requirement of Truth" in the 1990s, I said that I had

changed my mind because of the critical debates

around Sarob.

Figure 3: Description of the Story.

"In Uzbek literature, as in Soviet literature in the

1960s, the struggle between the two worldviews was

at its height," he said. The new wave broke the

traditional patterns and began to overflow the banks

like spring streams. But for those who have a different

opinion, who are loyal to the truth, who value

traditions, and who do not imagine life without

discipline, it was natural that this wave would seem

unacceptable and dangerous. Organized around the

Writers' Union, the internal struggle between the

powerful group and the more powerful ranks called

the disciples of Abdulla Qahhor, was fierce despite

the apparent peace and friendship.

How much such courage and bravery in his time

influenced the spiritual and literary life of our

country, opened the eyes of dozens of creative

intellectuals, in particular, set fire to the hearts of

young artists, the rulers of the dictatorial regime. And

it is clear to the general public that he is awake.

Qahhor's zeal, with his honest words, attracted like-

minded, genuine talents.

It should be noted that the house of Abdulla

Qahhor was founded not only by writers but also by

various leading scientists of their time: M. Urozbaev,

M. Kulmatov, T. Zohidov, Y. Toshpulatov, H.

Abdullayev, Sh. It has become a place of worship for

free-thinking public figures such as Khodjaev.

3 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we can say that Abdulla Qahhor is one

of the writers who vividly reflected the tragedy of the

time, the suffering of people, and social problems in

all his works, and left an indelible mark on our

literature with his works of genius. In his works, the

writer openly described the situation of people. With

his works, he strove to bring people oppressed by

Soviet oppression out of the spiritual quagmire. We

can see this from the stories analyzed above. Also, the

writer's careful approach to the depiction of nature,

and his ability to show environmental and ecological

problems in his works, increase the value of his

works. The reader also learns artistic pleasure and

environmental education through the works of the

writer.

REFERENCES

Karimov, N. (1999). Landscapes of 20th-century literature.

Tashkent: Akademnashr.

Sharafiddinov, O. (1988). Abdulla Qahhor. Tashkent:

Young Guard.

Koshjanov, M. (1984). Abdulla Kahhor skills. Tashkent:

Gafur Ghulam Publishing House of Literature and Art.

Abdullah Qahhor. (1987-1989). Works (5 volumes).

Tashkent: Publishing house named after Gafur Ghulam.

Mamiraliyev, Q. (2021). Some reviews on the mutation of

genres in Uzbek poetry. International Journal for

Innovative Engineering and Management Research,

10(3).

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

1088