Responsibility and Ecology: Leaders of Progress

Abdulla Ulug'ov

Tashkent State University of the Uzbek Language and Literature, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Keywords: Modern, Uzbek, Literature, Events, Social.

Abstract: Nazar Eshanqul holds a prominent position in modern Uzbek literature, skilfully reflecting life events and

human imagery in his stories and novels. His works are distinguished by their poetic language, vivid imagery,

and profound analysis of life's realities. Eshanqul's narratives uncover significant aspects often overlooked by

others. Works such as "The Black Book," "The Man Led by the Monkey," and "Untimely Played Bong"

resonate with deep poetic thought and passionate expression. They exemplify how the effectiveness of verbal

art lies in conveying profound, heartfelt experiences. In pieces like "You Can't Catch the Wind," "Night

Fences," and "Momo's Song," Eshanqul's wide-ranging observations and poetic expressions evoke the depth

of feeling akin to literary figures such as Fyodor Dostoevsky and Albert Camus. Characters in his works take

responsibility for Earth's fate, advocating for ecological preservation and rational energy resource usage,

cementing their status as timeless heroes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nazar Eshanqul's stories, short stories, novels, essays

and articles are not similar to the works of other

authors. His works are unique in every way. This can

be clearly seen in the reflection of life events, the

embodiment of characters, the form and style of the

works, the style of expression, and the construction of

sentences. The writer's stories such as "The Black

Book", "Night Fences", "The Wind Can't Be

Stopped", "The Man Led by the Monkey", "Untimely

Ringing" by Abdulla Kahhor, It is completely

different from the works of Said Ahmad or Shukur

Kholmirzaev, O'tkir Hashimov. "Thief", "Patient",

"Pomegranate", "Horror" (A. Qahhor), "Orik Domla"

(S. Ahmad), "Life Forever", "Blue Lake", "Freedom"

(Sh. Kholmirzaev), In the stories "The Last Victim of

the War" (O'. Hoshimov) a certain event is

impressively described. They are based on a certain

plot, there is a conflict between the characters, and the

events are clearly expressed. For example, the story

"The Patient": "Sotiboldi's wife fell ill. Sotiboldi

trained the patient - it didn't happen. He showed it to

the doctor. The doctor took blood. The patient's eyes

were closed, and his head became dizzy. Bakhshi

read. Some kind of woman came and beat him with a

willow stick, butchered a chicken and bled it. All this,

of course, is done with money. At such times, the

thick one is stretched, the thin one is cut off" (Kahhor

A. Works: Five volumes. Vol. 1. Sarob: Roman.

Stories. - T.: Adabiyot va sanat publishing house,

1987. - p. 336 - p. 289). Narration of events in this

way is also observed in the works of other artists. In

literature, it has been a tradition to convey life events

in the same form since time immemorial. In the works

of traditional style, the narration of events prevails. In

Nazar Eshanqul's stories and stories, analysis of the

essence of events takes a central place. In them, the

hero's experiences and the environment in which he

lives are approached artistically and philosophically.

The writer writes about the complex mental state and

conflicting experiences of the characters in their inner

world.

2 ANALYSIS

The characters in the writer's works who live with the

pain of the land and time, who call people to fight for

the purity of air, water, and soil ecology, and who

reflect the image of people who are worried about

preserving natural resources, can be shown in the

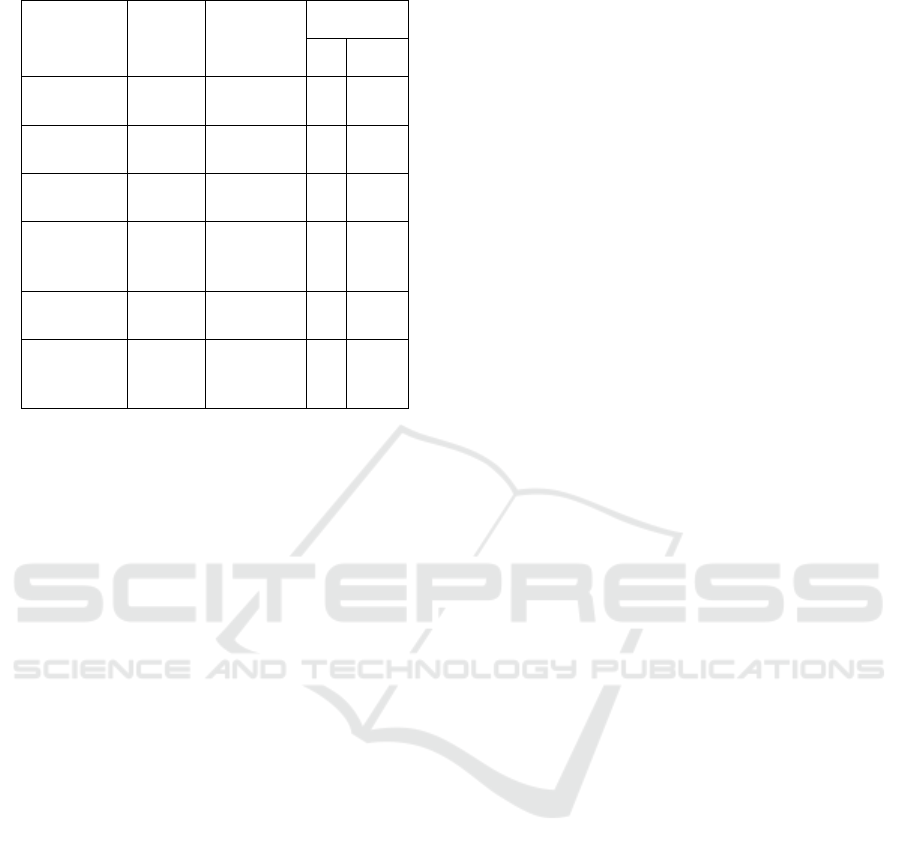

table as follows:

Ulug’ov, A.

Responsibility and Ecology: Leaders of Progress.

DOI: 10.5220/0012955900003882

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies (PAMIR-2 2023), pages 1167-1170

ISBN: 978-989-758-723-8

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

1167

Table 1: Writer’s Notable Work

Title of the

work

genre Total

number of

characters

of these

man woman

The Black

Boo

k

the

p

ovest

7 4 3

Night Fences the

p

ovest

5 2 3

Momo's

Song

the

p

ovest

5 3 2

The Man

Led by the

Monkey

the

novelle

3 2 1

Untimely

p

la

y

ed bon

g

the

novelle

4 2 2

You Can't

Catch the

Win

d

the

novelle

5 2 3

These characters stand out as someone who is

searching for answers to life's riddles. They are given

to their memories, think about their past and suffer.

The characters in "The Man Led by the Monkey,"

"The Black Book," and "The Early Bong" initially

create an impression of a person whose mind is

occupied by bad thoughts. But they do not clash with

others; they do not fight against anyone, like the

heroes in the works of Abdulla Qadiri, Aybek,

Abdulla Qahhor. The heroes of Nazar Eshanqul's

works debate with themselves and search for answers

to life's riddles. Many mysteries of the human soul are

revealed in their passionate internal discussion. The

characters of "You Can't Catch the Wind" and "The

Black Book" approach themselves and others with

high demands. From the discussion of these priceless

heroes who are looking for answers to the riddles of

life with themselves and with others, it is understood

that a person's life becomes meaningful only when he

directs his strength, abilities, and all his activities

towards noble and good goals. It is clear that the main

feature of the work of the author of "The Black Book"

is to show the inner world of a person full of

contradictions, the conflicting struggle in it. If you

compare the stories "The Wind Can't Be Catched,"

"The Man Led by the Monkey," or "Coffin" with the

stories "Horror," "Pomegranate," or "Thief," the

works of Abdulla Qahhor are in the direction of story

writing which is common in literature, and the works

of Nazar Eshanqul are in the direction of "stream of

consciousness" - it is clear that it was learned based

on the analysis and observation of events. In these

stories of the author of "Mirage," the life and

experiences of the heroes are skilfully described. The

reader will draw a clear conclusion about the reality

of these stories in just one reading. That is, he feels

sorry for some of the characters in them and hates

others. The stories "A Man Led by a Monkey," "The

Smell of Mint," "Invasion," "Night Fences," and "The

Black Book" are not among the works of this type that

are easy to read and clearly understand what is being

said. Although Abdulla Qahhor's stories are among

the high examples of traditional prose, if they are

compared to the stories "The Man Led by a Monkey,"

"Istilo," "Yalpiz Hidi," it becomes clear that Nazar

Eshanqul's stories reveal the psychological process of

the characters in a wider way. Not only clothes,

lifestyle, but also social-political, spiritual-

educational views, taste and level of people are

suitable for their times. Considering this fact, writers

such as Abdulla Qahhor and Oibek embodied human

life based on the literary criteria of their time. Their

works were considered a real innovation in Uzbek

literature at that time. But it is self-evident that any

innovation becomes obsolete with time. Although the

stories "Pomegranate" and "Dahshat" are considered

to be artistically perfect, now they have become

works depicting the human image in a traditional

direction. Now in Uzbek literature, there are works

that reflect the human nature and spiritual world in a

new way. In these works, revealing the conflicting

experiences of the characters plays a key role. Nazar

Eshanqul's stories and stories are among such works.

The characters in them seek to understand and

understand the complexities of life and self through

critical analysis of what they have seen and

experienced. It is important to feel and understand

something. Because a person learns the mysteries of

life through feeling and understanding.

In the core of "The Black Book" and "The Man

Led by the Monkey" lies the portrayal of individuals

who grapple with their sins and suffer as a

consequence. Artists strive to unravel the enigmatic

depths of human hearts, as expressed in Nazar

Eshanqul's protagonists, often writers or artists

themselves. Through their works, Eshanqul conveys

unique perspectives on literature, diverging from

conventional understandings. The characters in his

stories, nameless yet introspective, confront their

pasts and repent their mistakes, embodying goodness

amidst inner turmoil. They agonize over their

misdeeds, recognizing suffering as a purifying force

spiritually.

The absence of names in Eshanqul's protagonists

symbolizes universal dissatisfaction with life. In "The

Black Book," the protagonist's bitter realizations

reflect a sense of betrayal and disillusionment.

Similarly, in "The Man Led by the Monkey," the

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

1168

nameless artist grapples with the blurred lines

between good and evil, disillusioned by humanity's

flaws. Both characters represent a broader theme of

self-discontent and a search for meaning in a world

perceived as devoid of purpose. Through their

narratives, Eshanqul critiques societal decay and the

erosion of genuine spirituality amidst materialistic

pursuits.

After exploring the narrative, it becomes evident

that the title of the story carries dual meanings.

Initially depicting a young man leading a monkey out

of a dark forest, the artist's early work contrasts with

his later portrayal of a weary old man being led into

the woods. Through these illustrations, the

protagonist reflects on life's complexities, joys, and

sorrows, concluding that one's actions reveal their

true nature. The narrative underscores the struggle to

discern good from bad and the perennial quest for

answers amidst life's adversities.

Nazar Eshanqul's stories delve into everyday

occurrences with a creative and philosophical lens. In

"The Man Led by the Monkey," a young man

dwelling in a rented abode contemplates the solitary

and impoverished life of an adjacent artist. Through

nuanced observations, the story explores the artist's

retreat into abstraction and solitude as he grapples

with life's reflections. Unlike conventional heroes of

Uzbek literature, Eshanqul's characters confront the

enigmas of existence with dissatisfaction and

introspection, questioning the injustices and

complexities of societal norms. These narratives

resonate deeply, stirring contemplation on human

nature and the tangled web of human experience.

At the core of Nazar Eshanqul's works lies the

portrayal of suffering individuals. Initially appearing

engulfed in depression and despair, these melancholic

characters captivate attention and evoke sympathy

through profound contemplation on life and

compassion for others. Such an impression is

achieved through works expressing inner pain. "The

Black Book," "The Wind Can't Be Stopped," and

"The Early Bong" reflect deep sadness and longing

tormenting the human heart. In these narratives,

protagonists grapple with their mistakes and suffer,

emphasizing that the harshest punishment comes

from one's own conscience.

Nazar Eshanqul's narratives delve into heartache

caused by evil but differ significantly from traditional

works. In "The Black Book" and "The Man Led by

the Monkey," individuals are responsible for their

own lives, and happiness or unhappiness depends on

their perception. These works convey the pain and

suffering of individuals struggling to find their place

in life, resembling a stream of consciousness. In

contrast, traditional works often feature external

conflicts, whereas in Eshanqul's stories, protagonists

wrestle with themselves, undergoing self-denial and

suffering while expressing innermost thoughts and

experiences.

Nazar Eshanqul's characters stand apart in Uzbek

literature, distinct from conventional archetypes.

They are seekers grappling with life's mysteries,

portrayed as demanding and stubborn individuals.

Despite initial impressions of capriciousness and

sarcasm, they ponder human will and its significance

above all else. In works like "The Black Book" and

"The Man Led by the Monkey," protagonists lament

the prevalence of oppression, violence, and deceit,

which render people mentally enslaved. Their

relentless quest for answers to life's woes remains

unfulfilled, mirroring broader societal struggles

against selfishness and ambition.

Early 20th-century Uzbek literature critiqued

societal ills such as ignorance and laziness, whereas

mid-century saw strides in education and access to

modern knowledge. By the latter part of the century,

Uzbek literature transitioned to exploring universal

human dilemmas, transcending domestic concerns.

Eshanqul's characters, akin to those in Fyodor

Dostoevsky's and Albert Camus's works, reflect

existential solitude amidst crowded urban or rural

landscapes. Through protagonists like those in "The

Wind Can't Be Caught" and "The Man Led by the

Monkey," Eshanqul portrays desolation amidst

dilapidation, echoing broader themes of human

isolation and societal decay.

In stream-of-consciousness literature, character

portrayal holds paramount importance, with

appearance serving as a window into the inner world.

Characters weathered by life exhibit weariness, while

cheerful individuals exude a captivating charm.

Authors like Nazar Eshanqul masterfully craft their

characters' images, akin to skilled artists. Each

depiction is vivid, resembling a watercolor painting,

contrasting starkly with traditional works'

monochrome portraits. Eshanqul's characters,

plagued by despair and dissatisfaction, wear their

inner turmoil on their faces, rendering them ugly and

worn.

In traditional literature, character conflicts drive

narrative dynamics, revealing diverse outlooks and

personalities. Authors like Abdulla Qadiri convey

moral stances through character actions, fostering

clear condemnation or approval. Conversely, stream-

of-consciousness works focus inward, eschewing

external clashes. Eshanqul's narratives delve deep

into characters' inner conflicts, manifesting through

introspective dialogues. His protagonists grapple with

Responsibility and Ecology: Leaders of Progress

1169

existential questions, reflecting on past experiences

and seeking meaning amidst disillusionment.

Through these stories, Eshanqul prompts readers to

confront life's enigmas, fostering self-realization and

spiritual growth.

Bayna Momo, a teacher and artist plagued by the

existential quest for answers, emerges as a figure

initially weary of life, holding disdain for others' lack

of laughter. Despite this weariness, they possess

eloquence, engaging students with thought-

provoking inquiries in tales like "The Wind Can't Be

Caught." These characters, unlike those in renowned

stories such as "Spring Does Not Return" or "Listen

to Your Heart" by O'tkir Hashimov, offer invaluable

insights. Although they share traits with Nazar

Eshanqul's protagonists, they embody kindness,

always willing to aid those in need, contrasting

sharply with their seemingly weary appearance. In

Nazar Eshanqul's works, characters harbouring

resentment towards society do not inflict harm;

instead, they sacrifice for others' happiness, reflecting

pure intentions. Eshanqul's portrayal of invaluable

individuals diverges from traditional literature,

introducing a unique perspective to Uzbek literature.

Through their struggles and introspections, his

characters explore life's meaning, reflecting the

tumultuous era's complexities. Eshanqul's literary

finesse highlights the evolving landscape of Uzbek

literature, resonating with readers grappling with

similar existential dilemmas in today's globalized

world.

3 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Nazar Eshanqul emerges as a visionary

figure in modern Uzbek literature, whose works

transcend conventional storytelling to delve into the

profound complexities of human existence. Through

masterful narration and introspective character

portrayal, Eshanqul skillfully navigates the inner

landscapes of his protagonists, revealing their inner

turmoil, existential quests, and moral dilemmas. His

stories, such as "The Black Book" and "The Man Led

by the Monkey," serve as poignant reflections on the

human condition, prompting readers to contemplate

life's mysteries and societal injustices. Eshanqul's

unique blend of poetic language, philosophical depth,

and ecological advocacy establishes him as a leading

voice in contemporary literature, advocating for

responsibility towards ecological preservation and

rational energy resource usage.

Furthermore, Eshanqul's characters stand as

timeless heroes, grappling with their sins, seeking

redemption, and embodying the eternal struggle

between good and evil. Their introspective journeys

serve as mirrors to society, prompting readers to

confront their own inner conflicts and moral choices.

In a literary landscape marked by societal decay and

spiritual disillusionment, Eshanqul's narratives offer

glimpses of hope and resilience, reminding us of the

transformative power of self-reflection and

compassion. As Uzbek literature evolves to embrace

universal human dilemmas, Eshanqul's contributions

continue to resonate, inspiring readers to embark on

their own journeys of self-discovery and moral

awakening.

REFERENCES

Aitmatov, C. (1989). The day that made the century old;

Doomsday: The Novels. Tashkent: Literature and Art

Publishing House.

Aitmatov, C. (2007). Signs of the End Times: A Novel.

Tashkent; Publisher of the National Library of

Uzbekistan named after Alisher Navoi.

Dostmuhammad, K. (2000). The joys of free suffering.

Tashkent: "Spirituality".

Qahhor, A. (1987). Works: Five volumes. 1st vol. Mirage:

Novel. Stories. Tashkent: Literature and Art Publishing

House.

Rumi, M. J. (2004). Spiritual is spiritual. The sixth book (J.

Kamal, Trans.). Tehran: "Al-khuda" international

publishing house.

Sakharov, V. I., & Zinin, S. A. (2007). Literature of the XIX

century. Class 10: Uchebnik dlya

obshcheobrazavatelnyx uchrejdeniy: V 2ch. Ch. 2 (4th

ed.). Moscow: OOO "TID "Russkoe slovo - RS".

Veteran. (2007, April 13). Great song. Literature and Art of

Uzbekistan, 15.

An anthology of 20th century Uzbek stories. (2009).

Tashkent: "National Encyclopedia of Uzbekistan" State

Scientific Publishing House.

Shepherd. (1994). Literature is rare. Tashkent: "Cholpon".

Eshankul, N. (2007). The Man Led by the Monkey: Tales

and Stories. Tashkent: "New century generation".

Eshankul, N. (2008). Peppermint Smell: Stories and Tales.

Tashkent: "Sharq".

Eshankul, N. (2010, March 26). Human understanding is

the main criterion. Literature and Art of Uzbekistan.

Hamza, H. N. (1988). A complete collection of works. Five

roofs. Vol. 2. Poems. pedagogical pamphlets, prose

works. Tashkent: "Fan".

PAMIR-2 2023 - The Second Pamir Transboundary Conference for Sustainable Societies- | PAMIR

1170