What Do Customers Demand?

Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing

João M. S. Carvalho

1,2 a

1

REMIT, Portucalense University, R. António Bernardino de Almeida, 541, 4200-072, Porto, Portugal

2

CEG – Centro de Estudos Globais, Open University, Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords: Entrepreneurial Marketing, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Market Orientation, Inclusivity, Societal

Sustainability, CROWAI Model, ISEM Model.

Abstract: There is a lack of research that links start-ups' entrepreneurial marketing with the increased customers' demand

for inclusivity and sustainability. This paper proposes and substantiates a new conceptual model – Inclusive

and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing. This model includes the context and resources as the base for

value creation; objectives and entrepreneurial will for developing a business model, followed by planned and

unplanned actions, and inclusivity and societal sustainability as the significant impacts. The empirical

substantiation of the model followed a design-science approach and was done through 55 interviews with

entrepreneurs. Most entrepreneurs do not consider societal sustainability and inclusivity as primary objectives.

However, these goals present an increased prevalence among the customers' current requirements. This paper

contributes to the theoretical and empirical development of entrepreneurial marketing studies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today’s competitive environment is characterised by

increased risk, uncertainty, change, and more

demanding customers (Hills et al., 2008). Customers

expect quality and innovative products (goods,

services, ideas, experiences, information) from

organisations and inclusive, sustainable, and socially

responsible behaviours and products (Chiscano &

Jiménez-Zarco, 2021). As such, entrepreneurs and

managers should consider these demands to be more

successful in the market. Moreover, inclusivity and

sustainability became competitive advantages that

may allow for better financial performance of the

organisations (Longoni & Cagliano, 2018).

To cope with a context of limited resources and

uncertain markets, the need for a new perspective on

how organizations developed their entrepreneurial

and marketing strategies emerged, which turned out

to be the discipline of entrepreneurial marketing

(Alqahtani & Uslay, 2020). A recent paper reviews

the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0683-296X

This work was supported by the UIDB/05105/2020 Pro-

gram Contract, funded by national funds through the FCT

I.P.

(EM) and business sustainability (Al-Shaikh &

Hanaysha, 2023). However, there is not any study

relating EM to both inclusivity and sustainability.

Thus, there is a lack of research linking start-ups’

entrepreneurial marketing with the increased

customers’ demand for inclusivity and sustainability.

This study aims to fill that gap, presenting and

substantiating a conceptual evolution through a new

model that implies the response to the ethical market

demands related to inclusivity and sustainability,

called Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial

Marketing (ISEM). As such, our research question is:

What do entrepreneurs consider the more critical

aspects regarding entrepreneurial marketing, societal

sustainability, and inclusivity impacts?

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

EM concept was already latent in Murray's work

(1981) when he pointed out the need to discover new

Carvalho, J.

What Do Customers Demand? Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing.

DOI: 10.5220/0012201900003717

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2024), pages 13-24

ISBN: 978-989-758-695-8; ISSN: 2184-5891

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

13

product-market relationships instead of improving

marketing in already established markets.

Traditionally, marketing had been a discipline

predominantly focused on large organizations (Hills

et al., 2008). Then, EM emerged as an approach to the

characteristics and challenges faced by starting

entrepreneurs and small firms (Collinson & Shaw,

2001; Morris et al., 2002). Today, it can be suited for

all kinds of organizations (Kraus et al., 2010).

At the core of EM is value creation (Hills et al.,

2010; Kraus et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2002; Pane-

Haden et al., 2016) through an entrepreneurial

process that depends on the political, economic,

natural, social, cultural, and technologic context, the

availability of resources, the venture objectives, the

entrepreneur’s will, and planned and unplanned

actions (Carvalho, 2022; Sarasvathy, 2001). One can

say that EM can be added to complete the statement

of Lam and Harker (2015): if entrepreneurship is the

soul of a business and marketing is the flesh, then EM

should be the right mindset for entrepreneurs

(Alqahtani & Uslay, 2020).

Morris et al. (2002) proposed one of the most cited

definitions of EM and its dimensional design, which

includes the proactive identification and exploitation

of business opportunities, market orientation,

innovativeness, value creation, risk management, and

resource leveraging.

Based on Morris et al. (2002) and Kraus et al.

(2010), Eggers et al. (2020) presented EM as a

strategic orientation related to organizational

marketing attitudes and behaviours that are

entrepreneurial, defending that EM is a formative

construct based on entrepreneurial, innovation,

market, and customer orientations.

On the other hand, Alqahtani and Uslay (2020)

emphasised the stakeholders' role and defined EM as

"an agile mindset that pragmatically leverages

resources, employs networks, and takes acceptable

risks to proactively exploit opportunities for

innovative co-creation, and value delivery to

stakeholders, including customers, employees, and

platform allies" (p.64).

Other authors (e.g., Kilenthong et al., 2015, 2016;

Sodhi & Bapat, 2020) proposed six dimensions for

the EM construct: growth orientation, opportunity

orientation, total customer focus, value creation

through networks, informal market analysis, and

closeness to the market.

Following Eggers et al. (2020)' approach, one

considers that the EM construct is based on

entrepreneurial, innovation, and market orientations,

which could be its main formative dimensions, as is

also implicit in the study of Baker and Sinkula (2009).

However, the overlapping among EM, market

orientation (MO), and entrepreneurial orientation

(EO) must be clarified. Baker and Sinkula (2009)

considered that EO and MO are distinct but

complementary constructs, the former more related to

the entrepreneur’s will and action, and the latter

viewed as an intangible organizational resource

(Carvalho, 2022). Additionally, Narver et al. (2004)

distinguished between responsive and proactive MO,

which partially overlap the proactiveness dimension

of EO. To separate these two approaches to

proactiveness, Eggers et al. (2020) consider that

responsive MO is more about current and manifest

customer needs, and proactive MO is more related to

latent or future customer needs.

MO signifies a marketing strategy that implies the

organizational responsiveness to the market based on

its effort to obtain and generate market information

about the customers and other stakeholders, which is

the subject of internal dissemination and analysis,

with inter-functional coordination (Kohli & Jaworski,

1990; Narver & Slater, 1990). Consequently,

entrepreneurs must gather, leverage, and know how

to manage the resources needed to create value that

allows them to fulfil the identified opportunity in the

market, i.e., being customer and stakeholder-oriented

(Gorica & Buhaljoti, 2016). The relationship with

different stakeholders lies at the foundation of

entrepreneurial marketing, as this often represents a

capability that allows entrepreneurial ventures to gain

an advantage (Hills et al., 2008).

Market and marketing research are closely related

to MO. Entrepreneurs need to have good information

about the markets they want to serve. If they have

enough resources, they can do more formal marketing

research; otherwise, they will rely on their intuition or

knowledge, seeking more informal ways to know the

markets (Stokes, 2000). EM is extended to all types

of organizations, so one must consider all possible

approaches to gathering information.

The EO construct was proposed by Miller (1983),

including proactiveness, innovativeness, and risk-

taking. Hills and Hultman (2006) showed that when

EO is high, EM behaviours are more present. In this

context, innovation is crucial, namely concerning the

business model, which plays a critical role in making

the proposition value of a technology explicit

(Wallnöfer & Hacklin, 2013) and designing value

creation and value capturing (Zott et al., 2011).

Developing a new product and/or organization

may rely on planned or unplanned actions. Thus,

depending on the business environmental context and

available resources, the entrepreneurs must follow a

strategic or a business plan claimed by investors,

FEMIB 2024 - 6th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

14

donors, or lenders and/or use a non-causation path,

like effectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001), tinkering

(Barinaga, 2017), experimentation (Baum et al.,

2011), bricolage (Baker & Nelson, 2005),

bootstrapping (Harrison et al., 2004; Salimath &

Jones III, 2011), or pivoting (Blank, 2013; Ries,

2011).

Developing a new business model also appeals to

the traditional strategic marketing concepts of

segmentation, targeting, and positioning. Today’s

technology allows the possibility to customize most

products. Thus, customization is a competitive

advantage for any entrepreneur.

However, customers in wealthier countries are

demanding more from entrepreneurs. They want

organizations to be more inclusive, both from the

point of view of inclusion in the production of

socially or biologically disadvantaged people

(inclusiveness), as well as the need for the products

themselves to be inclusive, not discriminating against

anyone concerning their use or consumption

(inclusivity).

For example, Licsandru and Cui (2018) develop

the construct of subjective social inclusion in the

context of inclusive marketing, including acceptance

(feeling that other people wish to include them),

belongingness (cognitive judgement of fit and

emotional connectedness), empowerment (control,

contribution to, and self-efficacy), equality (equal

opportunities and chances), and respect (recognition

as a person) as its dimensions. This approach is

essential for entrepreneurs’ decision-making

regarding multi-ethnic and disadvantaged people

marketing communications and can be extant to

different levels of vulnerability: sexual orientation,

disability, gender, age, or social status (Licsandru &

Cui, 2018). Friedman et al. (2007) also talked about

multicultural marketing, which implies using

differentiated marketing strategies with diverse

ethnic, religious, and national groups.

The study of Reyes-Menendez et al. (2020)

presented results expressing the relevance of gender

equality at work and in communication campaigns,

defending that marketing advertisers should become

more inclusive and respectful. Rivera et al. (2020)

argued that entrepreneurs should manage diversity

and inclusion, by "developing inclusive products and

marketing strategies focused on people with

disabilities" (p.37). These authors defended that

education for inclusiveness is crucial to enable

students to recognize differences as assets that can

potentiate business. They explained the universal

design method to create inclusive products as a

condition of social sustainability (Smith & Preiser,

2011).

In this context, everybody benefits from inclusive

products and production. First, because entrepreneurs

have more people at their disposal to produce and

consume their products, it also gives an image of

social responsibility that benefits the organization and

the general well-being. Second, the identification of a

brand with specific social groups has positive and

negative effects (Mishra & Bakry, 2021): consumers'

preference for a brand could be associated with a

social group they belong to or want to belong to

(Escalas & Bettman, 2003) or, on the contrary, they

prefer to avoid the association with a particular social

group and, consequently, they do not buy that brand

(White & Dahl, 2007). Thus, being inclusive in

producing and marketing activities may avoid this

negative group identification.

Although ‘inclusiveness’ and ‘inclusivity’ may be

considered synonymous (Cambridge Dictionary), it is

noticed that the term ‘inclusivity’ is more used in the

literature. It seems that ‘inclusivity’ is a more

dynamic approach related to practice or policy aiming

to include people who are excluded or marginalized,

such as those with physical or mental disabilities or

are members of minority groups. On the other hand,

‘inclusiveness’ may be seen as a characteristic that

already exists, related to embracing all people or

objects.

Inclusive marketing is congruent with MO,

requiring a strategic orientation to manage diversity

with equity and justice sustainably (Ruiz-Alba et al.,

2019).

This study considers societal sustainability as a

fundamental issue for customers, namely in rich

countries. Following previous studies (e.g., Carvalho,

2019), sustainable entrepreneurship presents four

dimensions: (1) economic, which is related to the

capacity of the product to satisfy human needs as a

condition of the financial sustainability of the

organizations; (2) ecological, related to the

preservation of the natural capital (planet,

environment, biodiversity, climate); (3) social,

implying the preservation of social cohesion in terms

of well-being, nutrition, shelter, health, education,

quality of life, etc.; and (4) psychological, that means

achieving and maintaining positive emotional states,

improving physical and mental health balance, and

personal perception of the quality of own’s life

(Carvalho, 2016; European Commission, 2011). All

these dimensions are linked, and their interaction

contributes to societal development and sustainability

(Assefa & Frostell, 2007; Carvalho, 2016).

What Do Customers Demand? Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing

15

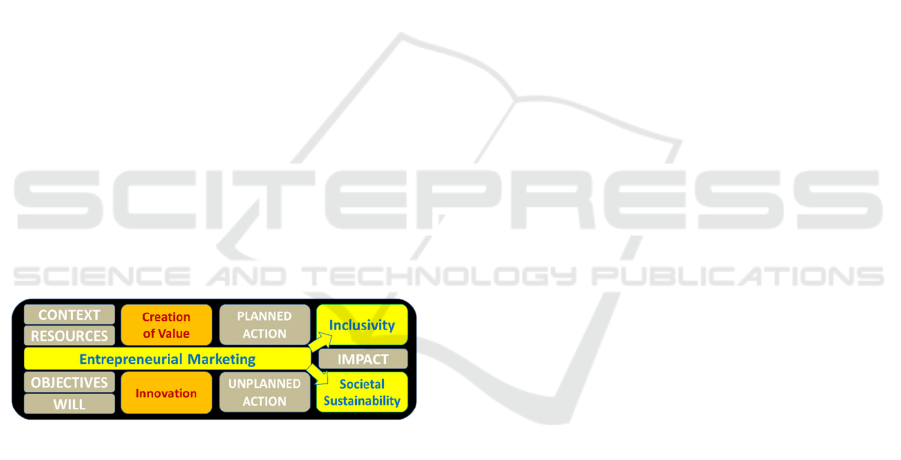

This research uses the concepts related to EM

studied in previous research, arranging them within

the framework of the intra/entrepreneurial process

model (CROWAI – context, resources, objectives,

will, action, impact) developed by Carvalho (2022).

This paper defends that inclusivity and societal

sustainability should be privileged in modern

entrepreneurship, implying that all the variables of

the CROWAI model are aligned with those desirable

impacts. The context and available resources must

allow the development of inclusive and sustainable

ventures, which nowadays are more effortless,

particularly with the technological advances of recent

years with this type of concern. Of course, the

entrepreneur needs to have these goals and the will to

achieve them. These goals imply planning in that

sense but do not prevent the use of unplanned actions

to pursue the entrepreneurial action successfully.

However, how sensitive are entrepreneurs to

issues of inclusivity and societal sustainability?

Which factors were considered more important

when they developed their ventures?

The empirical part of this paper will provide an

updated answer to these questions.

This paper uses the concepts related to EM studied

in previous research, arranging them within the

framework of the intra/entrepreneurial process

developed by Carvalho (2022). Figure 1 presents the

model that summarizes the main concepts around the

proposed construct of inclusive and sustainable

entrepreneurial marketing (ISEM).

Figure 1: ISEM model.

After the analysis of all definitions and

descriptions of entrepreneurial marketing, inclusivity,

and societal sustainability (not all presented in this

paper) and following the recommended approaches

(e.g., Podsakoff et al., 2016), one came to a definition

of the new construct: Inclusive and Sustainable

Entrepreneurial Marketing is about the creation of

customer value and a business model through the

exploration and/or identification of a societal need in

a specific activity context and resource availability,

which leads to the establishment of objectives and an

entrepreneurial will to achieve stakeholders’

satisfaction, and more inclusive and sustainable

society, through planned and unplanned actions.

3 METHODS

The research method was based on a design-science

approach, which has the potential to validate artifacts,

such as constructs, models, methods, and

instantiations, and fill up the theory-practice gap (e.g.,

Rosemann & Vessey, 2008). After the theoretical

substantiation of the model constructs, which together

are aligned with the ISEM model, it is presented the

three-stage approach based on the widely accepted

guidelines in design science research (e.g., Peffers et

al., 2008): (1) Problem Definition, (2) Design and

Development, and (3) Evaluation.

3.1 Problem Definition

This study aims to fulfil the lack of research about

organizational EM and customers today’s demand for

products that, besides satisfying their needs, can also

contribute to societal inclusivity and sustainability. For

this purpose, this study started with the theoretical

substantiation of the well-established EM construct

and the concepts of inclusivity and societal sustaina-

bility, which can be considered objectives and impacts

of the entrepreneurial process (Carvalho, 2022).

3.2 Design and Development

ISEM model is pictured presenting the core concepts

that are more accepted in the literature. Following

other published models that describe the

entrepreneurial process (e.g., Carvalho, 2022), the

ISEM model considers that the entrepreneurs must

cope with exogenous variables (context and

resources) through market orientation, marketing

research, and resource management to explore and

identify a business or a social opportunity. Then, they

use entrepreneurial orientation ability to analyse the

endogenous variables (entrepreneurial will and

objectives), assessing the opportunity, the risks

involved, their innovative capacity to create a

solution, and being proactive in their efforts to

achieve their objectives. At last, they decide to create

and develop the product and/or organization, taking

into account the new demands of the markets related

to inclusivity and societal sustainability in the

production, marketing, and impact phases.

The questionnaire follows the CROWAI model

approach (Carvalho, 2022). It is a conceptual and

practical systematisation of the entrepreneurial

process, starting from the context and resources

available to create something new, passing through

the entrepreneurs' goals and personal will, which can

FEMIB 2024 - 6th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

16

lead to an entrepreneurial action with an impact on

society.

The nine interview questions allowed multiple

responses, which implies only a descriptive statistical

analysis measured by the percentage of entrepreneurs

in the sample that expressed each particular answer.

3.3 Evaluation

To test the ISEM model’s accuracy in describing what

today concerns entrepreneurs, one performed 55

interviews with owners of start-ups launched in the last

five years. This period is enough to guarantee that the

start-ups overcame the first years of implementation

and that the entrepreneurs can more easily reflect on

what they have done to achieve success.

It was decided to carry out a snowball sample to

guarantee that a reasonable number of entrepreneurs

would accept to answer the interview survey. Each

entrepreneur was asked to contact two other

entrepreneurs they knew to minimize the refusals to

participate in this study. In the first phase, the author

identified five entrepreneurs related to creating new

companies who agreed to participate in the research,

and these interviewees identified another ten

entrepreneurs. Even so, in this second phase, only

eight entrepreneurs accepted the interview and

indicated another 16 potential participants. One

failed, obtaining the identification of another 30

entrepreneurs, having in this last phase failed three.

Thus, it was obtained a total sample of 55

entrepreneurs as follows: 35 created a new company

with known products; 12 created a new company with

a new product; and eight were equally divided among

those who launched a new product in their existing

company, those who created a new social

organization, those who created a new social product

in an existing organization, and those who created a

new project or profitable product in the company they

worked for. Therefore, six of the respondents are

intrapreneurs. Table 1 presents the profile of the

participants in this study.

Table 1: Description of the sample.

Sex n (%)

Average age

(SD)

High

School

Professional

education

University

education

Female

24

(43.6)

32.79

(9.04)

6 3 15

Male

31

(56.4)

35.26

(10.74)

6 0 25

SD – Standard deviation

All the entrepreneurs agreed to respond to the

questionnaire during the interview, signing an

informed consent. They knew that their participation

would be strictly voluntary, anonymous, and

confidential, that obtained data would be for

statistical treatment only, and that no answer would

be analysed or reported individually. Our ethical

commission considered it unnecessary to assess or

produce an official authorization for this research

because no personal or sensitive data were involved

or collected in this study.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The question related to the context when the

entrepreneur decided to launch a new product,

project, or organization was: When you thought about

becoming an entrepreneur or launching a new

product, service, business model, or social

responsibility project, what favourable conditions

existed in the political, economic, social, cultural and

technological context? (Table 2).

The most critical item was the existence of a

business opportunity in the market identified by the

entrepreneur (67.3% of the entrepreneurs).

Table 2: The context.

Contextual favourable conditions %

There was a business opportunity in the market 67.3

Entrepreneurship training was available 32.7

There was a societal need that was not satisfied or poorly satisfied 30.9

I had a social support network 29.1

There were other people and/or groups interested in my business 29.1

The social environment was favourable to the new business 25.5

There was the possibility of strategic alliances 21.8

The business or innovation ecosystem was favourable 14.5

There were public and/or private institutions favourable to the new venture 10.9

I take advantage of entrepreneurship-friendly public policies or programs 7.3

There was a business opportunity from within the company where I work 7.3

The social sector welcomed this new venture 7.3

There were research and development networks 3.6

It was possible to innovate with the contribution of the community 3.6

Entrepreneurial spirit and motivation of the initial team 3.6

There were no favourable conditions in the social, economic and legislative

context

3.6

It follows the availability of entrepreneurial

training (32.7%); the existence of a societal need that

was not satisfied or was poorly satisfied (30.9%);

having a social support network (29.1%); there were

other people and/or groups interested in their business

(29.1%); the social environment was favourable to

the new business (25.5%); and there was the

possibility of strategic alliances (21.8%).

These results confirm the importance of the

existence of an opportunity for exploration and

exploitation (e.g., Gorica & Buhaljoti, 2016; Renton

& Richard, 2020), the opportunity to attend

What Do Customers Demand? Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing

17

entrepreneurial education or professional training

(e.g., Higgins et al., 2013; Kuratko, 2005), the

identification of a societal need that is not satisfied

being market-oriented (e.g., Eggers et al., 2020; Kohli

& Jaworski, 1990), the entrepreneur's network of

personal relationships (e.g., Aaboen et al., 2013;

Elfring & Hulsink, 2007), being flexible and open to

stakeholders' collaboration (e.g., Alqahtani & Uslay,

2020; Most et al., 2018), and a favourable social

environment (e,g., Hills et al., 2008; Kostetska &

Berezyak, 2014). All these contextual dimensions are

included in the entrepreneurial marketing concept, as

well as the others that present less expression in this

study.

The question related to the resources when the

entrepreneur decided to launch a new product,

project, or organization was: What resources did you

need to be able to design, produce, and implement

your product, service, business model, or project?

(Table 3).

The most critical items were the existence of

financial (100% of the participants), and physical or

material (78.2%) resources.

Table 3: The resources.

Resources %

Financial resources 100

Physical or material resources 78.2

Market orientation 63.6

Strategic planning 61.8

Human resources or human capital 50.9

Innovation capacity 50.9

Intellectual capital (human, organizational and relational) 45.5

Intellectual assets (trademark, copyright, trade secrets, contracts, patents) 43.6

Knowledge management 34.5

Internal competitive advantages 32.7

Dynamic capabilities 30.9

Organizational learning 27.3

Sustainable competitive advantages 21.8

Core competencies 7.3

It is worth noting that the resources needed by

more than 50% of entrepreneurs also include human

resources (50.9%), as well as three capabilities

closely related to entrepreneurial marketing: market

orientation (63.6%), strategic planning (61.8%), and

innovation capacity (50.9%). Many studies pointed

out the relevance of these resources (e.g., Carvalho,

2012, 2020, 2022; Covin et al., 2016; Eggers et al.,

2012; Eggers et al., 2020; Eggers & Kraus, 2011;

Morris et al., 2002; Ostendorf et al., 2014).

The question related to value creation was: What

factors were crucial for creating value in your

entrepreneurial project? (Table 4).

The most critical items were the importance of

intuition in decision-making (76.46 of the

participants), the focus on customers’ needs (69.1),

efficient management of resources (65.5), monitoring

customers’ satisfaction (61.8), and decision-making

based on exchanging information within the

entrepreneur’s networks (58.2). All the items were

chosen by the participants, reinforcing the role of

value creation in its diverse aspects.

Table 4: Value creation.

Factors %

It was important to believe in our intuition to make decisions 76.4

The focus on the customer or consumer needs was crucial 69.1

We always seek to manage the available resources efficiently 65.5

We constantly monitor the level of customer satisfaction 61.8

Many marketing decisions were based on exchanging information with

people in our personal and professional networks.

58.2

We get the collaboration of customers or consumers to create value 47.3

We have collaborated with industrial partners and friends to create value 40.0

Our employees contributed new ideas for value creation 36.4

Some decisions were not taken due to the existence of excessive risks 34.5

Information about successes and failures is transmitted to our employees 29.1

There were limitations on access to material resources 25.5

There were limitations on access to intellectual resources 25.5

There were limitations in access to financial resources 23.6

Project risk management has been carefully studied 23.6

The new project or product did not involve much formal market research 20.0

There was good cross-functional coordination to respond to the market 16.4

There were limitations in access to human resources 16.4

We get the collaboration of suppliers and distributors to create value 10.9

These main issues corroborate what is mentioned

in the literature, namely the use of intuition or

informal ways to know the markets (e.g., Stokes,

2000), the use of entrepreneurial and market

orientations to face uncertain economic contexts (e.g.,

Eggers et al., 2012; Eggers & Kraus, 2011), the more

efficient use of the resources (e.g., Jones & Rowley,

2011), and the crucial role of entrepreneurs’ networks

(e.g., Aaboen et al., 2013; Elfring & Hulsink, 2007).

One can notice the relationship of value creation with

the context and the resources available for a new

venture, as depicted by the ISEM model.

The question related to product characteristics

was: What characteristics does the new product

present (good, service, idea, experience,

information), social project, or business model?

Table 5 shows that the most critical items were

economic value (89.1% of the participants), the

profitability of the product (65.5%), psychological

value depicted by increased open-mindedness

(50.9%), and greater self-confidence (50.9%).

Some aspects related to psychological value

(third, fourth, and sixth items in Table 5) are more

FEMIB 2024 - 6th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

18

chosen than those related to social and ecological

values (e.g., Carvalho and Sousa, 2018).

Table 5: Product characteristics.

Product characteristics %

Satisfies the need of the customer or consumer. 89.1

Is it a sufficiently profitable product or project 65.5

Contributes to a mindset more open to new ideas 50.9

Contributes to greater self-confidence 50.9

It allowed the creation of new jobs. 49.1

Contributes to a healthy change in attitudes or behaviours 45.5

Contributes to improving the quality of life, safety, or health in society 38.2

Provides new knowledge or skills 38.2

It is an environmentally friendly product or project 21.8

Contributes to greater awareness of harmful discrimination 21.8

Contributes to the preservation of animal species or flora 10.9

The question related to innovation was: In what

aspects is the new product (good, service, idea,

experience, information), social project, or business

model innovative?

Table 6 shows that the most critical items were

product differentiation or innovation (69.2% of the

participants), business model innovation (61.5%),

marketing communication (55.8%), customization of

the product (44.2%), and process innovation (42.3%).

Table 6: Innovation.

Innovation aspects %

It is a differentiating/innovative product or project in terms of

features/benefits for customers or consumers

69.2

We managed to innovate in terms of our business model 61.5

Marketing communication follows a different paradigm from the

competition

55.8

The product can be customize

d

44.2

One or more of the processes followed (production, logistics, distribution,

marketing, customer relations, payment, etc.) is innovative in the context of

the activity.

42.3

The pricing system is different from the competition 36.5

Our employees make a difference in the product on the market 34.6

The product or project has the collaboration of public or private partners 26.9

Our advertising includes images with cultural, sexual, and age diversity. 23.1

We were able to innovate in terms of our social or profit purposes 19.1

We managed to innovate in terms of product distribution 15.4

The product can be used by people with mental or physical disabilities 15.4

The product is also promoted to ethnic minorities 13.5

One of the dimensions of EM mentioned in the

literature is innovativeness (e.g., Covin et al., 2016),

and/or innovation orientation (e.g., Eggers et al.,

2020), and/or marketable innovation (e.g., Alqahtani

& Uslay, 2020). Thus, this study confirms all the

aspects predicted in the literature related to

innovation. In particular, business model innovation

plays a critical role in making explicit a value

proposition (e.g., Wallnöfer & Hacklin) and its design

and capture (e.g., Zott et al., 2011). A business model

depends on the product type and the entrepreneur’s

objectives and will to create a new market offer

and/or a new organization.

The question related to entrepreneurs’ objectives

was: What specific goals did you aim for with the new

product, service, business model, or project?

(Table 7) shows that the most critical items were

the will to be an entrepreneur (65.5% of the

participants), create a new product (65.5%), innovate

(58.2%), contribute to societal sustainability (41.8%),

and create a new business model (27.3%). However,

one can notice that societal sustainability and

inclusivity are not the main objectives of the majority

of these entrepreneurs. Several studies (e.g., Chiscano

& Jiménez-Zarco, 2021; Longoni & Cagliano, 2018)

have demonstrated the importance for consumers of

aspects related to inclusivity and societal

sustainability and their positive impact on

organizational financial performance.

Table 7: The objectives.

Objectives %

To be an entrepreneur 65.5

Create a new value proposition 65.5

Innovation 58.2

Contribute to societal sustainability (

economic, social, ecological, psychological) 41.8

Create a new business model 27.3

To have a corporate social responsibility program 10.9

Contribute to social inclusion 10.9

To be a social entrepreneu

r

7.3

Contribute to digital inclusion 5.5

Social innovation 3.6

To be an intrapreneur (entrepreneur in the company where you work) 3.6

To be a social intrapreneu

r

3.6

To be an inclusive entrepreneur 3.6

The question related to the entrepreneurial will

was: What factors contributed to your being an

entrepreneur?

Table 8 shows that they are entrepreneurs mainly

because they strongly desire to be one (100% of the

participants). Many (74.5%) are constantly looking

for new business opportunities or creating something

new. The entrepreneurs view themselves as people

with technical (69.1%), leadership (61.8%), thinking

and analysis (56.4%), influence (54.5%), goal

achievement (52.7%), and people and group

management (49.1%) skills. All the aspects predicted

Table 8: The entrepreneurial will.

Factors contributing to being an entrepreneur %

Own will 100

I am constantly looking for new business opportunities or creating

something new

74.5

I have technical skills 69.1

I have leadership skills 61.8

I have thinking and analysis skills 56.4

I have the ability to influence others 54.5

I have goal-achievement skills 52.7

I have people and group management skills 49.1

I have (had) businesspersons or entrepreneurs in the family 49.1

I have enough knowledge 49.1

I like to take the initiative in every situation 49.1

I have sel

f

-management skills 47.3

I have the necessary psychological capital 40.0

I have high emotional intelligence 30.9

I look for new societal needs to satisfy 30.9

The available human and social capital were an excellent motivation 27.3

I got an entrepreneurship education 23.6

What Do Customers Demand? Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing

19

in this construct are present, confirming its

importance reported in the literature (e.g., Bird, 2015;

Fine et al., 2012; García, 2014).

The question related to the action was: What

fundamental actions helped you to carry out your

project?

Table 9 shows that the most critical items were the

non-planned way to develop their businesses, namely

adjusting small details (81.8% of the participants),

improvising (63.6%), improvising without financial

support (58.2%), adapting to contingencies (58.2%),

and using experimentation (50.9%). Other important

action issues focused on the customers (60%) and the

commitment despite difficulties (58.2%). One can

notice here, again, that market orientation and the

entrepreneurial will guide action. It is interesting to

find that, besides the fact that 61.8% of the

entrepreneurs (Table 3) considered strategic planning

as a fundamental resource, a significant majority

confirmed that they used tinkering (e.g., Barinaga,

2017), bricolage (e.g., Baker & Nelson, 2005),

bootstrapping (e.g., Salimath & Jones III, 2011;

Winborg & Landström, 2001), pivoting (e.g., Blank,

2013; Ries, 2011), effectuation (e.g., Sarasvathy,

2001), and experimentation (e.g., Baum et al., 2011).

However, entrepreneurial action views are

compatible and complementary (Carvalho, 2022;

Fisher, 2012). Many authors (e.g., Carvalho &

Jonker, 2015; Moroz & Hindle, 2012) defended that

planning is necessary when an entrepreneur wants to

achieve specific goals, namely in terms of access to

resources, processes’ organization, or public and

private support. All entrepreneurial processes can be

helpful, depending on the business context,

development stage, and objectives the entrepreneurs

want to achieve.

Table 9: The action.

Actions %

I was adjusting small details throughout the process 81.8

I was improvising and doing, overcoming the limitations 63.6

Our strategy has always focused on understanding the needs of our

customers or consumers.

60.0

I improvised without external financial support, managing the available

resources well

58.2

I kept adapting to contingencies, uncertainties and risks, creating solutions 58.2

I felt committed to succeeding despite all the difficulties 58.2

I've been using some experimentation throughout the process 50.9

I changed the organizational strategy depending on the context of the

activity

43.6

We have achieved a very relevant strategic positioning 41.8

Our employees have the motivation to overcome difficulties 40.0

I always managed to overcome the constraints of the project or business 36.4

Our employees have always adjusted to the needs 30.9

Our employees have the necessary training and skills for all situations 30.9

The entrepreneurial action was thoroughly planne

d

27.3

I had to plan a lot of steps because of the programs I was in 16.4

I used a design thinking approach 14.5

We did an excellent segmentation of the market 14.5

I had to plan the business as required by the financier or partner 9.1

The question related to the impact was: What are

the impacts of your new product, service, business

model, or project? (Table 10).

Table 10: The impact.

Impacts %

I managed to achieve my goals partially 47.3

I achieved all my goals 40.0

I managed to reduce the financial costs 36.4

I achieved economic and financial sustainability 34.5

I managed to contribute to improving the quality of life in society 34.5

I contributed to psychological sustainability (people’s psychological

b

alance, etc.)

30.9

I was able to improve the financial performance of the organization 29.1

I managed to contribute to the increase in social inclusion 27.3

I managed to contribute to the development of the territory (local, regional

or national

21.8

I managed to contribute to ecological sustainability (environmental

p

reservation, etc.)

18.2

I contributed to social sustainability (social cohesion, social equity, etc.) 10.9

I managed to reduce non-financial costs 3.6

The most critical items were goals’ achievement,

partially (47.3% of the participants) and entirely

(40%), the reduction of financial costs (36.4%), the

achievement of economic and financial sustainability

(34.5%), improvement of quality of life in society

(34.5%) and contributing to psychological

sustainability (30.9%).

As expected, the economic and financial viability

of the new ventures is crucial for the entrepreneurs.

They are also pleased to have managed to win in the

market by ensuring the survival of the organization,

product, or project so far.

What is interesting is their consideration of

customers’ psychological sustainability besides

social sustainability. This result reinforces the idea

that entrepreneurs seek some kind of positive results

with their customers besides the social impact of their

businesses.

It seems that many of these entrepreneurs do not

privilege ecological sustainability. However, all the

possible impacts have less than 50% of the

entrepreneurs’ agreement. Today’s customers are

increasingly demanding (Hills et al., 2008), including

concerns about organizational inclusivity,

sustainability, and socially responsible behaviours

(Chiscano & Jiménez-Zarco, 2021). Entrepreneurs

and managers should consider these demands to

succeed in the market. Inclusive and Sustainable

Entrepreneurial Marketing could be the way to

achieve those goals.

5 CONCLUSIONS

There is a lack of research that links start-ups’

entrepreneurial marketing with the increased

customers’ demand for inclusivity and sustainability.

FEMIB 2024 - 6th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

20

Based on the literature, this paper proposes and

substantiates a conceptual model that considers

Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing

(ISEM) within the entrepreneurial process: context,

resources, objectives, entrepreneurial will, action,

and impact. The empirical substantiation of the

model, following a design-science approach, was

done through 55 interviews with entrepreneurs.

In the business context, a market opportunity

identified by the entrepreneur is the primary response,

followed by the availability of entrepreneurial

training, a societal need, and a social support network.

Regarding business resources, entrepreneurs must

have access to financial, material, and human

resources and use market orientation, strategic

planning, and innovation capacity.

In the domain of the objectives, they preferred

their will to be entrepreneurs, followed by the

creation of a new product, innovation, contribution to

societal sustainability, and creation of a new business

model.

The entrepreneurial is based essentially on their

desire, followed by constantly looking for new

business opportunities or creating something new.

Regarding action, entrepreneurs preferred non-

planned ones to adjust their businesses over time.

However, when the business context demands a

strategic plan, they consider that tool essential to their

success. At the beginning of their projects, it seems

they try to follow strategic planning, which needs to

be complemented by improvisation to resolve the

business developing problems better.

Finally, the impacts related to entrepreneurs’

ventures were achieving their goals, followed by

economic, financial, social, and psychological

sustainability. However, one can notice that societal

sustainability and inclusivity are not the main

objectives of the majority of these entrepreneurs,

which could be a problem for them in market

competition.

Entrepreneurial marketing is evident in the

answers of these entrepreneurs, combining

entrepreneurial, market, and innovation orientations.

To create value and decision-making, they seemed to

rely a lot upon their intuition and focus on customers’

needs and the efficient management of resources.

They were concerned with the product’s profitability

and psychological value (impact on individual lives).

The majority also look for product and business

model innovation and marketing communication.

Inclusive and multicultural marketing, as well as

societal sustainability issues, are on the current

agenda of economics, marketing, and management

studies because consumers are more demanding, and

entrepreneurs should listen to the market to be

successful. Thus, this exploratory paper aims to

contribute to the research stream of entrepreneurial

marketing, highlighting the importance of inclusive

and sustainable entrepreneurial impacts.

Another critical aspect of this study was the

possibility of discussing with the interviewed

entrepreneurs many of these concepts and alerting

them to the importance of market orientation,

innovation, planning, inclusivity, and societal

sustainability.

This paper also shows that EM can be combined

with the entrepreneurial process as a new analysis

tool for entrepreneurial behaviour.

The limitations of this study involve the use of a

snowball sample made in only one country. Thus, this

study cannot be generalized to all entrepreneurs’

populations. However, the sample has a great

diversity of ventures and entrepreneurs, providing

reasonable indications about what is happening now.

Future research can better explore entrepreneurial

marketing aiming at inclusivity and societal

sustainability by using larger samples in several

countries and measuring the variables to validate a

future model that could explain a significant part of

the population variance.

REFERENCES

Aaboen, L., Dubois, A. and Lind, F. (2013), “Strategizing

as networking for new ventures”, Industrial Marketing

Management, Vol.42 No.7, pp.1033–1041.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.07.003

Alqahtani, N. and Uslay, C. (2020), “Entrepreneurial

marketing and firm performance: synthesis and

conceptual development”. Journal of Business

Research, Vol.113, pp.62-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.jbusres.2018.12.035

Al-Shaikh, M.E. and Hanaysha, J.R. (2023), “A conceptual

review on entrepreneurial marketing and business

sustainability in small and medium enterprises”, World

Development Sustainability, Vol.3, 100039.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wds.2022.100039

Assefa, G. and Frostell, B. (2007), “Social sustainability

and social acceptance in technology assessment: A case

study of energy technologies”, Technologies in Society,

Vol.29, pp.63–78.

Baker, T. and Nelson, R.E. (2005), “Creating something

from nothing: resource construction through

entrepreneurial bricolage”, Administrative Science

Quarterly, Vol.50 No.3, pp.329–366. https://doi.org/

10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329

Baker, W.E. and Sinkula, J.M. (2009), “The

complementary effects of market orientation and

entrepreneurial orientation on profitability in small

What Do Customers Demand? Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing

21

businesses”, Journal of Small Business Management,

Vol.47 No.4, pp.443–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1540-627X.2009.00278.x

Barinaga, E. (2017), “Tinkering with space: the

organizational practices of a nascent social venture”,

Organization Studies, Vol.38 No.7, pp.937–958.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616670434

Baum, J.R., Bird, B.J. and Singh, S. (2011), “The practical

intelligence of entrepreneurs: antecedents and a link

with new venture growth”, Personnel Psychology,

Vol.64 No.2, pp.397–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1744-6570.2011.01214.x

Bird, B. (2015), “Entrepreneurial intentions research: a

review and outlook. International Review of

Entrepreneurship, Vol.13 No.3, pp.143-168.

Blank, S. (2013), “Why the lean startup changes

everything”, Harvard Business Review, Vol.91 No.5,

pp.63–72.

Carvalho, J.M.S. (2012), “Planeamento Estratégico – O seu

guia para o sucesso” [Strategic Planning. Your guide to

success], Grupo Editorial Vida Económica: Porto,

Portugal.

Carvalho, J.M.S. (2016), “Innovation & Entrepreneurship.

Idea, Information, Implementation, Impact”, Grupo

Editorial Vida Económica: Porto, Portugal.

Carvalho, J.M.S. (2019). Social Innovation,

Entrepreneurship, and Sustainability. In Information

Resources Management Association (Ed.), Social

Entrepreneurship: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools,

and Applications (chap. 01, pp. 1-34). Hershey, USA,

IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-8182-

6.ch001

Carvalho, J.M.S. (2020), “Organizational toughness facing

new economic crisis”, European Journal of

Management and Marketing Studies, Vol.5 No.3,

pp.156-176. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejmms.v5i3.873

Carvalho, J.M.S. (2022). Modelling (social) intra/

entrepreneurship process. Emerging Science Journal,

6(1), 14-36. https://doi.org/10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-01-

02

Carvalho, J.M.S. and Jonker, J. (2015), “Creating a

Balanced Value Proposition – Exploring the Advanced

Business Creation Model”, Journal of Applied

Management and Entrepreneurship, Vol.20 No.2,

pp.49-64. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.3709.2015.a

p.00006

Carvalho, J.M.S. and Sousa, C.A.A. (2018), “Is

psychological value a missing building block to societal

sustainability?” Sustainability, Vol.10 No.12, 4550.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124550

Chiscano, M.C. and Jiménez-Zarco, A.I. (2021), “Towards

an inclusive museum management strategy. An

exploratory study of consumption experience in visitors

with disabilities. The case of the CosmoCaixa Science

Museum”, Sustainability, Vol.13, 660. https://doi.org/

10.3390/su13020660

Collinson, E. and Shaw, E. (2001), “Entrepreneurial

marketing—a historical perspective on development

and practice”, Management Decision, Vol.39 No.9,

pp.761-766. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006

221

Covin, J.G., Eggers, F., Kraus, S., Cheng, C.-F. and Chang,

M.-L. (2016), “Marketing-related resources and radical

innovativeness in family and non-family firms: a

configurational approach”, Journal of Business

Research, Vol.69 No.12, pp.5620–5627.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.069

Eggers, F., Hansen, D.J. and Davis, A.E. (2012),

“Examining the relationship between customer and

entrepreneurial orientation on nascent firms' marketing

strategy”, International Entrepreneurship and

Management Journal, Vol.8 No.2, pp.203–222.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-011-0173-4

Eggers, F. and Kraus, S. (2011), “Growing young SMEs in

hard economic times: the impact of entrepreneurial and

customer orientations - a qualitative study from Silicon

Valley”, Journal of Small Business and

Entrepreneurship, Vol.24 No.1, pp.99–111.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2011.10593528

Eggers, F., Niemand, T., Kraus, S. and Breier, M. (2020),

“Developing a scale for entrepreneurial marketing:

revealing its inner frame and prediction of

performance”, Journal of Business Research, Vol.113,

pp.72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.0

51

Elfring, T. and Hulsink, W. (2007), “Networking by

entrepreneurs: patterns of tie-formation in emerging

organizations”, Organization Studies, Vol.28 No.12,

pp.1849–1872. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084060707

8719

Escalas, J.E. and Bettman, J.R. (2003), “You are what they

eat: the influence of reference groups on Consumers'

connections to brands”, Journal of Consumer

Psychology, Vol.13 No.3, pp.339–348. https://doi.org/

10.1207/S15327663JCP1303_14

European Commission (2011), “Mental Well-Being: For a

Smart, Inclusive and Sustainable Europe”, Retrieved

January 15, 2015, from http://ec.europa.eu/health/men

tal_health/docs/outcomes_pact_en.pdf

Fine, S., Meng, H., Feldman, G. and Nevo, B. (2012),

“Psychological predictors of successful entrepreneur-

ship in China: an empirical study”, International

Journal of Management, Vol.29 No.1, pp.279-292.

Fisher, G. (2012), “Effectuation, causation, and bricolage:

a behavioral comparison of emerging theories in

entrepreneurship research”, Entrepreneurship: Theory

and Practice, Vol.36 No.5, pp.1019–1051.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00537.x

Friedman, H.H., Lopez-Pumarejo, T. and Friedman, L.W.

(2007), “Frontiers in multicultural marketing: the

disabilities market”, Journal of International Marketing

and Marketing Research, Vol.32 No.1, pp.25–39.

Gorica, K. and Buhaljoti, A. (2016), “Entrepreneurial

marketing: evidence from SMEs in Albania. American

Journal of Marketing Research, Vol.2 No.2, pp.46-52.

Harrison, R.T., Mason, C.M. and Girling, P. (2004),

“Financial bootstrapping and venture development the

software industry”, Entrepreneurship and Regional

FEMIB 2024 - 6th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

22

Development, Vol.16 No.4, pp.307–333.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0898562042000263276

Higgins, D., Smith, K. and Mirza, M. (2013),

“Entrepreneurial education: reflexive approaches to

entrepreneurial learning in practice. Journal of

Entrepreneurship, Vol.22 No.2, pp.135–160.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0971355713490619

Hills, G.E., and Hultman, C.M. (2006), “Entrepreneurial

marketing”, Lagrosen, S. and Svensson, G. (Eds.),

Marketing– Broadening the Horizon, Studentlitteratur,

Lund, Sweden, pp.219-234.

Hills, G.E., Hultman, C.M., Kraus, S. and Schulte, R.

(2010), “History, theory and evidence of

entrepreneurial marketing–an overview”, International

Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation

Management, Vol.11 No.1, pp.3–18. https://doi.org/

10.1504/IJEIM.2010.029765

Hills, G.E., Hultman, C.M., and Miles, M.P. (2008). The

evolution and development of entrepreneurial

marketing. Journal of Small Business Management,

46(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-

627X.2007.00234.x

Jones, R. and Rowley, J. (2011), “Entrepreneurial

marketing in small businesses: a conceptual

exploration”, International Small Business Journal,

Vol.29 No.1, pp.25–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266

242610369743

Kilenthong, P., Hills, G.E. and Hultman, C.M. (2015), “An

empirical investigation of entrepreneurial marketing

dimensions”, Journal of International Marketing

Strategy, Vol.3 No.1, pp.1-18.

Kilenthong, P., Hultman, C.M. and Hills, G.E. (2016),

“Entrepreneurial orientation as the determinant of

entrepreneurial marketing behaviors”, Journal of Small

Business Strategy, Vol.26 No.2, pp.1-21.

Kohli, A.K. and Jaworski, B.J. (1990), “Market orientation:

the construct, research propositions, and managerial

implications” Journal of Marketing, Vol.54 No.2, pp.1–

18. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251866

Kostetska, I. and Berezyak, I. (2014), “Social

entrepreneurship as an innovative solution mechanism

of social problems of society”, Management Theory

and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure

Development, Vol.36 No.3, pp.567–577.

https://doi.org/10.15544/mts.2014.053

Kraus, S., Harms, R. and Fink, M. (2010), “Entrepreneurial

marketing: moving beyond marketing in new ventures”,

International Journal of Entrepreneurship and

Innovation Management, Vol.11 No.1, pp.19–34.

https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2010.029766

Kuratko, D.F. (2005), “The emergence of entrepreneurship

education: development, trends, and challenges”,

Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, Vol.29 No.5,

pp.577–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.20

05.00099.x

Lam, W. and Harker, M.J. (2015), “Marketing and

entrepreneurship: an integrated view from the

entrepreneur's perspective”, International Small

Business Journal, Vol.33 No.3, pp.321–348.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613496443

Licsandru, T.C. and Cui, C.C. (2018), “Subjective social

inclusion: a conceptual critique for socially inclusive

marketing”. Journal of Business Research, Vol.82,

pp.330-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.0

8.036

Longoni, A. and Cagliano, R. (2018), “Inclusive

environmental disclosure practices and firm

performance: the role of green supply chain

management”, International Journal of Operations and

Production Management, Vol.38 No.9, pp.1815-1835.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-12-2016-0728

Miller, D. (1983), “The correlates of entrepreneurship in

three types of firms”, Management Science, Vol.29

No.7, pp.770–791.

Mishra, S. and Bakry, A. (2021), “Social identities in

consumer-brand relationship: the case of the Hijab-

wearing Barbie doll in the United States ethnic

identities in the multicultural marketplace”, Journal of

Consumer Behavior, Vol.20, pp.1534–1546.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1965

Moroz, P.W. and Hindle, K. (2012), “Entrepreneurship as a

process: toward harmonizing multiple perspectives”,

Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, Vol.36 No.4,

pp.781–818. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.201

1.00452.x

Morris, M.H., Schindehutte, M. and LaForge, R.W. (2002),

“Entrepreneurial marketing: a construct for integrating

emerging entrepreneurship and marketing

perspectives”, Journal of Marketing Theory and

Practice, Vol.10 No.4, pp.1–19. https://doi.org/

10.1080/10696679.2002.11501922

Most, F., Conejo, F.J. and Cunningham, L.F. (2018),

“Bridging past and present entrepreneurial marketing

research”, Journal of Research in Marketing and

Entrepreneurship, Vol.20 No.2, pp.229–251.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JRME-11-2017-0049

Murray, J.A. (1981), “Marketing is home for the

entrepreneurial process. Industrial Marketing

Management, Vol.10 No.2, pp.93–99. https://doi.org/

10.1016/0019-8501(81)90002-X

Narver, J.C. and Slater, S.F. (1990), “The effect of a market

orientation on business profitability”, Journal of

Marketing, Vol.54 No.4, pp.20-34. https://doi.org/

10.2307/1251757

Narver, J.C., Slater, S.F. and MacLachlan, D.L. (2004),

“Responsive and proactive market orientation and new-

product success”, Journal of Product Innovation

Management, Vol.21 No.5, pp.334–347.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-6782.2004.00086.x

Ostendorf, J., Mouzas, S. and Chakrabarti, R. (2014),

“Innovation in business networks: the role of leveraging

resources”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol.43

No.3, pp.504–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmar

man.2013.12.018

Pane-Haden, S., Kernek, C. and Toombs, L. (2016), “The

entrepreneurial marketing of trumpet records”, Journal

of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, Vol.18

No.1, pp.109–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRME-04-

2015-0026

What Do Customers Demand? Inclusive and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Marketing

23

Peffers, K., Tuunance, T., Rothenberger, M.A. and

Chatterjee, S. (2008), “A design science research

methodology for information systems research”,

Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol.24

No.3, pp.45–77. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-

1222240302

Renton M. and Richard, J.E. (2020), “Entrepreneurship in

marketing: socializing partners for brand governance in

EM firms”, Journal of Business Research, Vol.113,

pp.180-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.0

3.012

Reyes-Menendez, A., Saura, J.R. and Filipe, F. (2020),

“Marketing challenges in the #MeToo era: gaining

business insights using an exploratory sentiment

analysis”, Heliyon, Vol.6, e03626. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03626

Ries, E. (2011), “The Lean Startup: How Today's

Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create

Radically Successful Businesses”, Crown Business:

New York, NY, USA.

Rivera, R.G., Arrese, A., Sádaba, C. and Casado, L. (2020),

“Incorporating diversity in marketing education: a

framework for including all people in the teaching and

learning process” Journal of Marketing Education,

Vol.42 No.1, pp.37–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0273475319878823

Rosemann, M. and Vessey, I. (2008), “Toward improving

the relevance of information systems research to

practice: The role of applicability checks”, MIS

Quarterly, Vol.32 No.1, pp. 1–22. https://doi.org/

10.2307/25148826

Ruiz-Alba, J.L., Nazarian, A., Rodríguez-Molina, M.A. and

Andreu, L. (2019), “Museum visitors’ heterogeneity

and experience processing, International Journal of

Hospitality Management, Vol.78(April), pp.131-141.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.12.004

Salimath, M. and Jones III, R. (2011), “Scientific

entrepreneurial management: bricolage, bootstrapping,

and the quest for efficiencies”, Journal of Business and

Management, Vol.17 No.1, pp.85-103.

Sarasvathy, S.D. (2001), “Causation and effectuation:

toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to

entrepreneurial contingency”, Academy of

Management Review, Vol.26 No.2, pp.243–264.

https://doi.org/10.2307/259121

Smith, K.H. and Preiser, W.F.E. (2011), “Universal design

handbook”, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, USA.

Sodhi, R.S. and Bapat, R.D. (2020), “An empirical study of

the dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing”,

Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, Vol.24 No.1,

pp.1-7.

Stokes, D. (2000), “Putting entrepreneurship into

marketing: the processes of entrepreneurial marketing”,

Journal of Research in Marketing and

Entrepreneurship, Vol.2 No.1, pp.1-16. https://doi.org/

10.1108/14715200080001536

Wallnöfer, M. and Hacklin, F. (2013), “The business model

in entrepreneurial marketing: a communication

perspective on business angels' opportunity

interpretation” Industrial Marketing Management,

Vol.42, pp.755–764. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmar

man.2013.05.012

White, K. and Dahl, D.W. (2007), “Are all out-groups

created equal? Consumer identity and dissociative

influence”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol.34

No.4, pp.525–536. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/520077

Winborg, J. and Landström, H. (2001), “Financial

bootstrapping in small businesses: examining small

business managers’ resource acquisition behaviors”,

Journal of Business Venturing, Vol.16 No.3, pp.235–

254. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00055-5

Zott, C., Amit, R. and Massa, L. (2011), “The business

model: recent developments and future research,

Journal of Management, Vol.37 No.4, pp.1019-1042.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311406265

FEMIB 2024 - 6th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

24