Implications and Perceptions of Digital Health Technologies:

A Multiple Case Study on the Payers’ Viewpoint

Kai Gand

1a

, Hannes Schlieter

1b

, Elena Torrente Segarra

2

and Andreea Garaiacu

3

1

Research Group Digital Health, TUD Dresden University of Technology, Dresden, Germany

2

Digital Health Development, Digital Health Innolab, DKV, Barcelona, Spain

3

National Health Insurance House, Bucharest, Romania

Keywords: Digital Health Technologies, eHealth, Case Study, Survey.

Abstract: The study delves into the implications and perceptions of Digital Health Technologies (DHT) within the

healthcare system. Among the many relevant stakeholders, the present study’s objective is to explore the

perspective of health insurers particularly. On this, we have conducted a survey (1 face-to-face interview, 5

online questionnaires) for a multiple case study on lessons from European health insurance entities from 5

countries regarding usage scenarios of DHT. Recognized for their transformative potential, DHT promises to

address demographic shifts, streamline payment processes, and enhance patient management, especially for

chronic diseases. However, the survey participants still see challenges in terms of their long-term effectiveness,

demographic and regulatory constraints. Countries like Germany have pioneered regulatory frameworks, but

issues of trust and interoperability persist. The economic implications of DHT present both potential cost

savings and financial burdens. Health insurers emerge as pivotal players, acting as gatekeepers for DHT

quality and driving adoption. As the DHT landscape evolves, continuous evaluation, adaptation, and multi-

stakeholder collaboration are paramount for harnessing their full potential.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Problem Statement

The demographical development in Western

healthcare systems increases the morbidity of

patients. Particularly, non-communicable diseases

(NCDs), such as diabetes, hypertension, asthma,

depression, and anxiety, impose a substantial health

and economic burden on society (Vandenberghe &

Albrecht, 2020). To address this challenge, healthcare

delivery must rapidly shift from traditional processes

to scalable digital health technologies (DHT; (Digital

Therapeutics Alliance, 2023)). DHT (such as

technology-supported blended care, patient

monitoring, digital diagnostics, digital therapeutics)

offer the potential to improve the quality, efficiency,

and accessibility of healthcare (Chaudhry et al., 2006;

Stroetmann et al., 2010).

However, there are still significant challenges to

the sustainable and scalable implementation and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2065-8523

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6513-9017

diffusion of DHT. One key challenge is developing

and implementing effective business models that can

support the long-term adoption and use of DHT

(Gand, 2017; Veit et al., 2014). Another challenge is

ensuring that DHT are accessible and reasonably

priced or affordable for all stakeholders, including

those in underserved and low-income communities

(Suter et al., 2009). The fact that there are many

different stakeholders in the healthcare system

(various healthcare providers, health insurance

companies, patients, politicians) or the importance of

managing health-related data very carefully (cf.,

implications regarding privacy and security concerns)

are major challenges for the implementation as well.

To address these challenges, the present study’s

objective is to bring together the perspectives of

payers and academics to discuss emerging business

models of DHT. Thus, the research objective is to

explore this perspective of health insurers

particularly.

Gand, K., Schlieter, H., Segarra, E. and Garaiacu, A.

Implications and Perceptions of Digital Health Technologies: A Multiple Case Study on the Payers’ Viewpoint.

DOI: 10.5220/0012401800003657

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024) - Volume 2, pages 871-878

ISBN: 978-989-758-688-0; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

871

1.2 Methods

To address these open points, we have conducted a

multiple case study (Yin, 2014) on lessons learned

and perspectives from health insurance companies

regarding usage scenarios of DHT. A survey (1 as

face-to-face interview, 5 as online questionnaires) has

been used to get the respective insights. Details on the

survey modes can be found in the appendix (see Table

4). The two survey modes are equally important

sources of evidence with qualitative data for the

overall case study. The participants and the

organizations they represent constitute the partial

cases in the sense of a replication design of the overall

case study (Yin, 2014). The problem areas outlined

above are operationalized in terms of the survey with

the individual questions listed in Table 1 (Q#) and

discussed in the corresponding sections in Chapter 2.

The questions correspond to the elements of the

questionnaire and the key questions of the interview.

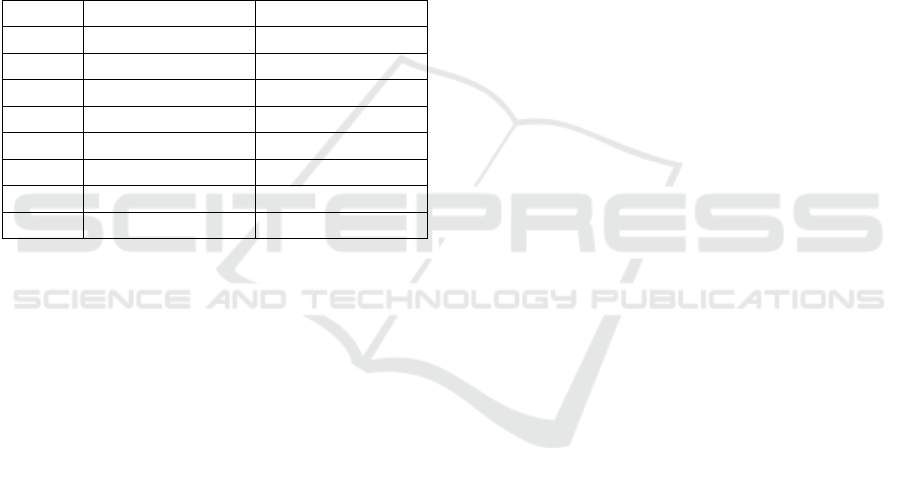

Table 1: Details on the survey elements.

No. Questions

Q1 – Sec.

2.1

How important are DHT for healthcare in

general?

Q2 – Sec.

2.1

How important are DHT from the payer's point

of view?

Q3 – Sec.

2.1

How can DHT help to make healthcare ready

for the future developments?

Q4 – Sec.

2.1

How can DHT be used for prevention, healthy

longevity, healthy aging, and elderly care?

Q5– Sec.

2.2

How to cope with the economic burden of

NCDs (with or without DHT)?

Q6 – Sec.

2.2

Which emerging business models of DHT are

p

romising?

Q7 – Sec.

2.4

What needs to change in terms of regulations to

make DHT successful?

Q8 – Sec.

2.3

Do you see a change in the role of health

insurances in the future (given the rise of DHT

or in general)?

Q9 – Sec.

2.5

Are you offering DHT? Did you develop these

DHT yourself or are you partnering with start-

ups or other companies?

Q10 – Sec.

2.5

Which DHT are already used and reimbursed?

In which fields? How are these paid for?

Q11 – Sec.

2.5

For which diseases do you think we need DHT

most? Where do you think DHT will work

b

est?

Q12 – Sec.

2.5

What is your main goal in offering these DHT?

(new revenue streams, cost-efficiency,

customer loyalty)

Q13 – Sec.

2.6

What learnings did you generate? Are there

DHT that worked better than others?

Q14 – Sec.

2.7

Could you already assess the effectiveness

and/or efficiency of DHT?

Q15 – Sec.

1.2

Details of the representatives / respondents

The Europe-wide professional network of the

authors (contacts via the membership lists of two

European associations accessible to the authors were

contacted; total number of contacted not known) was

used to look for suitable representatives of the payer

or insurer side in the healthcare system (note: given

the various healthcare systems, some with direct state

reimbursement, some with private or public health

insurers, the terms "payer" and "insurer" should be

understood interchangeably here). If the feedback

was positive, they were invited to participate in the

survey. Table 2 provides an overview of the survey

participants/analysis units of the case study.

Table 2: Overview of the representatives (R#) included -

details on the analysis units of the case study.

No. Country Characteristics (pseudonymised)

R1 Hungary Central national agency for the

management of the National Health

Insurance, maintenance of records,

keeping financial accounts and

fulfilling reporting obligations

R2 The

Netherlands

Trade, interest, liaising organisation of

companies offering health insurance;

b

alances different interests in healthcare

R3 Romania Public, autonomous national

institution to ensure unitary and

coordinated functioning of the social

health insurance system

R4 Spain Private health insurance with more

than 50,000 customers that offers

access to the medicine and other

related insurance services

R5 Germany Statutory (=non-profit, for the

common good), nationally represented

health insurance with more than

500,000 insured

p

eo

p

le

R6 Germany Biggest statutory (=non-profit, for the

common good), nationally represented

health insurance with more than 11

million insured

p

eo

p

le

In principle, a larger number of participants

would have been possible by using the survey

instrument. In the context of the case study, however,

the resulting number was considered sufficient after

one follow-up reminder for the members of the

requested associations.

2 INSIGHTS ON THE USE OF

DHT

In general, we have chosen a summary perspective for

the study. In the case of special aspects of individual

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

872

participants, these are reported specifically (see their

no. as displayed in Table 2). Partly, the given answers

did not fully fit the questions or if the participants

could not give an answer. When analysing the

answers, these have been partly clustered and

summarised to understand and address better the

primary study aim.

2.1 General Aspects

First, we asked the participants to rate the importance

of DHT from their point of view on a 5-point Likert

scale (Q1+Q2; see Table 3). For both, we got mostly

high ratings (meaning (very) high importance) -

putting digitisation as a cornerstone of healthcare.

Table 3: Responses for Q1 and Q2 (5-point Likert scale).

Q1 Q2

R1 4 4

R2 3 3

R3 5 5

R4 4 4

R5 4 4

Mean 4 4

Median 4 4

Mode 4 4

Further on, we requested the participants’ views

on DHT’s role in making healthcare ready for future

developments. In this regard, on the more

strategic/overarching level the participants mention a

possible reduction in the pressure on healthcare

providers, as remote access, for example, would make

it easier to implement more efficient processes and

overcome physical distance, thus reducing the overall

costs of healthcare delivery, and helping to prevent

illnesses (R1,4). Overall, DHT are associated with the

hope of being able to address larger demographic

changes, such as the lowering number of workers.

Operationally, payment processes and access (also to

medical) information could be facilitated, expensive

duplicate examinations could be avoided with

digitally available data (imaging procedures are

particularly expensive in this regard and could often

be easily reduced in number, which would also reduce

radiation exposure). DHT could also help patients

manage their chronic diseases by offering measures

to monitor relevant vital parameters, help establish

changes and offer support in everyday life (R1-6). It

is important to stress that these effects can only be

attained if the DHT offer a real benefit for patients

and medical staff and are used on a voluntary basis

(R5).

2.2 Economic Perspective

DHT help the payers to have very actual statistics

regarding the situation of all diseases and can make

optimised distributions of payments on that basis

(R3). On the other side, by creating consciousness of

how behaviour affects patients' disease, the economic

burden that comes with it could be alleviated. This is

achieved through earlier treatment or the avoidance

of the illness or deterioration due to a behaviour that

is better suited to one's own condition. DHT can, at

least in principle, offer the potential to provide more

constant support than is possible, for example,

through occasional visits to the doctor (R2,5,6).

The best way to cope with NCDs would be to

prevent them. With regards to the demographic

change, it would need a prompt major change in

individual behaviour of people and the circumstances

they live in, to nudge a healthier lifestyle. But with

regards to the ageing population, there also needs to

be an investment in secondary and tertiary

prevention, meaning that these diseases can be

detected at an early stage and empower patients with

NCDs to manage their disease. DHT could be

respective means and, in this sense, investments. If

these investments get reimbursed by a healthier

population is, however, uncertain (R5).

In addition to investments, business models

should also be considered as part of the advantages,

compensation, or benefits of these investments

(Mettler, 2016). However, scaling DHT also

generates additional costs. It may also not be clear

how or to what extent these additional costs can be

offset. Partly, the insurers' budgets are relatively

rigid. It is also questionable whether the healthcare

providers will be willing to pass on the efficiency

gains associated with digitalisation (cost shift away

from personnel towards infrastructure) or to accept a

corresponding change in budget structures. On the

other hand, to realise the benefits, it would also be

necessary to consider how patients or users of DHT

could be more effectively incentivised. Direct cash

benefits are sometimes difficult. If necessary,

agreements in the pharmaceutical sector would also

be conceivable. This would allow to control better

that less expensive but still effective drugs are used.

On a small scale, some existing prevention or bonus

programmes already have incentive mechanisms

(small payments or monetary-like benefits), which

might be expandable. Such mechanisms might then

also go hand in hand with a changed relationship

between the insured and the insurance in the direction

of a stronger companionship (R6).

Implications and Perceptions of Digital Health Technologies: A Multiple Case Study on the Payers’ Viewpoint

873

2.3 Potential Shift of the Role of Health

Insurers

There is a growing interest of health insurances in the

DHT market, and adoption models are being

considered to a greater extent. The participants see a

shift towards putting more pressure to adopt proven

DHT in healthcare through their purchasing power

(R1,2). Also, there is a shift towards more

preventative care and shared decision-making. It will

become more and more important that health

insurances guarantee the quality of the healthcare

system by only reimbursing DHT and other means

that have proven their positive effect. Health

insurances will be some kind of gatekeeper for high-

quality healthcare (R5). Also, they should act as a

gatekeeper and driver for using data. As particularly

highlighted in the case of Germany (R5,6; probably

true also for others), since a lot of valuable data is

stored on the statutory health insurance’s side, it

might or should be their future role to use this data to

improve healthcare. This data can be analysed on an

individual level (e.g., to find risk factors for serious

health threads) or on an aggregated level (allowing

population risk factor analyses). Data will also

be/need to be made available through the EHDS

(European Commission, 2023a), even increasing the

need for effective digitisation.

An interesting approach could also be that

patients or insured persons are more strongly guided

through the still complicated processes of the

healthcare system (where he/she must go, which steps

are pending) by DHT on the insurer side. Also, a kind

of pre-analysis of symptoms plus greater use of video

consultations could be possible to speed up processes

and enable control with increasingly limited

resources. As another example, it would be

interesting if the data of the healthcare service

providers were directly available to the health

insurance funds. A quick pre-check based on the

planned treatment would be conceivable in this way

(the concrete design for compatibility with the GDPR

remains to be seen). A second opinion could be

offered to be able to provide more information about

a cost-intensive and possibly risky treatment. The

autonomy of the individual would and should, thus,

be strengthened by the support of DHT. Digitalisation

could thus be seen as an opportunity to guide and

direct more, which hardly ever happens today. This

would result in an approach of hybrid treatment or

blended care (R6). Additional restrictions on the part

of the Medical Device Regulation (MDR; (European

Commission, 2023b)) could then also have to be

considered.

2.4 Regulations

First, broad access to DHT is important so that no user

(both on the patient and healthcare provider side) is

excluded (R1). This also touches on issues of

interoperability and usability of DHT (Katehakis &

Kouroubali, 2019). To achieve a uniform solution that

does not distort competition, pan-European

regulation is desirable. The direction currently being

taken by the legislator, including better use of (health)

data, is certainly conducive to a better basis and

ultimately also acceptance of DHT (R6; see, for

example, the recent European Data Governance Act

(European Commission, 2023c)).

For the case of Germany (R5,6), the situation is a

bit special as the country pioneered the field of DHT

(formally called “DiGA” - German abbreviation for

Digital Health Application) by making them

reimbursable by the statutory healthcare system back

in 2020 (Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical

Devices, 2023a). So, it is not the regulation that is

holding back the success of DHT, but rather a lack of

trust and fear of transparency of some stakeholders.

Interoperability challenges also remain. For example,

no data-side connection is currently possible between

DiGAs and the official electronic health record. Also,

specifications for data interfaces are not yet binding

or clear enough so that DHT solutions can always

function similarly. However, a basic framework

would be sufficient. Detailed regulations and the

concrete design could certainly be left to the

individual actors avoiding overregulation (R6).

2.5 Reasons and Modes to Offer DHT

There may be a general positive opinion about DHT.

But offering or even developing DHT is another

matter. R1 has no offer here now. For R2, at least

some healthcare insurers offer various DHT in

various fields. These are mostly offered through

third-party developers - not developed in-house.

Payment also ranges from self-pay to basic insurances

to private additional insurance. Also for R4, there are

DHT offered - both in-house developments and in

partnerships with external companies. In general,

telemedicine is a common offering nowadays.

Payment models vary without a common policy.

Overall, the participants have only limited

capacity to act as providers or developers of DHT

themselves. Therefore, they are also dependent on

what software providers offer and can only partially

control which areas and diseases DHT focus on (R1).

Selectability is partly seen as a non-existent luxury,

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

874

as the transformation agendas towards digitalisation

are still in the conception phase (R2).

As primary goals for using DHT, the participants

name enabling patient access, cost efficiency (R1-5),

maintaining quality and affordability of care and the

healthcare system. In fact, the system can only be

maintained if innovative solutions such as DHT are

used (R2,5). Also, DHT can increase the loyalty of

customers/insured people, improve the system on the

technical part and add more services, cover more

diseases (R3,4). It should also be noted that even large

to very large insurers may not necessarily have a

target group that matches the demographic and

population characteristics of the overall population.

For example, if younger people and families are the

target group, the focus may be more on DHT for

pregnant women (R6).

In general, a particular need for DHT is seen

mostly in the field of management of chronic diseases

(R4,5). Monitoring the health status (with various

means) would also be a reasonable area DHT can

contribute easily (R2,4,5). On that basis, patients may

establish changes in everyday life to become healthier

(R5). Also for R3, the available DHT are offered

rather in the management of diseases. DHT can also

offer good added value, especially around

psychological support, or mental illness. Here it is

particularly important that help is found at an early

stage and at a very low threshold. Shame and social

acceptance are still problematic with mental issues.

The anonymity of DHT (compared to face-to-face

therapy) could be particularly advantageous in this

sense (given that mental health issues are still often

shameful). Simple but very effective analogue means

such as diaries and daily or nutritional advice are also

very easy to transfer and make available in DHT (R6).

DHT also make it easier to deal with cases that are

still difficult today in general, such as the coverage of

(rarer) foreign languages or also the connection of

remote (foreign-language or very specialised)

doctors. Precision and clarity (not only but also

linguistically) are essential (R6). Health insurances

need (and want) to ensure high-quality healthcare as

some kind of gatekeeper to ensure an efficient and

effective use of means (R5).

For Germany (R5,6), the situation is again a bit

special. The statutory health insurances must fully

reimburse the DiGAs, which are listed by the Federal

Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (German

abbreviation: BfArM) and prescribed by a physician

to a patient (with no additional costs for them).

Furthermore, the health insurances can reimburse

DHT, which are not (yet) part of this list, via special

contracts and offer DHT of their own (choice). In this

case, the data flow can also be controlled much more

easily, user statistics are available. Due to the

complicated legal situation of the public health

insurance funds in Germany, only a few participate

directly in developers but rather buy or license the

DHT from external providers (R6).

Regarding focus, the DHT listed by BfArM are

mostly for the management of diseases, and only a

few are for prevention. The role of the gatekeeper for

quality results from the fact that offers from the health

insurance funds are either checked via the BfArM

procedure or come into reimbursement via selective

contracts and thus become attractive for patients

because they receive the offers on prescription.

Google and Co. are (so far) pushing into the second

healthcare market, where offers are paid for

themselves, and these are not officially checked (also

with a view to data protection). However, there is a

limit here (in the German market) with "lifestyle"

offers because these are generally not reimbursed by

the statutory health insurance (R5).

There was the further comment that electronic

patient records should also be counted as DHT and

very important ones at that. Especially from the

insurers' point of view, there is a great added value

here, as significantly better data availability goes

along with it. In Germany, in particular, the records

have a somewhat difficult public image, but their use

is increasing.

2.6 General Learnings

From the participants' experiences with the offer of

DHT, some generalisable experiences emerge. For

example, clinical validation or proof of benefit is

considered central. However, this is difficult to

achieve, especially for software development start-

ups (as service providers), partly because they lack

experience. So, also the buying/licensing side

somehow stays with this kind of uncertainty. It is

crucial that a good, clear use case/minimal viable

product is defined so that everyone knows what

benefit the DHT can provide or address (R4). Also,

there are already some insights on the distinct use of

DHT (R5): These are mostly used by women. As

already mentioned, DHT are usually developed for

one specific disease, which does not necessarily

reflect the full needs of the patients. That could be

problematic for those who suffer from further

diseases (co-morbidities). Patients often do not

complete the whole recommended treatment cycle.

This, in turn, reduces the overall added value of

implementing DHT.

Implications and Perceptions of Digital Health Technologies: A Multiple Case Study on the Payers’ Viewpoint

875

It is also interesting that the obvious group of

presumed digital affine people (<40 years) are partly

not so much in the focus on the use or offer of DHT

(apart from more specific target groups such as

pregnant women). This group is simply less affected

by diseases, so the benefit expectation in relation to

DHT is lower. Thus, it is rather the 40–60-year-olds

where the need for support through DHT is greater or

content for filling the electronic health record is

available because there is already a certain medical

history. In the meantime, a certain digital competence

is also available. Nevertheless, the digitally more

affine society is growing, so that user-side limitations

will certainly decrease in the future (R6; (United

Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2021)).

If there is a failure of DHT (or their lack of

sustainable use or upscaling), this can have further

causes. A DHT may have been developed for a very,

probably too specific purpose. In such cases, the DHT

was not able to cope with the complexity of the

overall system in real-life use, or its overall added

value was too low, and it could not be cost-effective

(R2,5). The situation is similar if the use case is

poorly designed, i.e., not very appropriate to the

needs or the healthcare system (R4). Or, in some

cases, the provisionally assumed clinical/medical

benefit does not materialise in the form of greater

practical benefit, so further use was discontinued (this

was the case, for example, with some DiGAs that

were delisted by the BfArM again; R6; (Federal

Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices, 2023b)).

2.7 Learnings Regarding Effectiveness

and Efficiency of DHT

Another kind of experience is that, so far, hardly any

statements can be made on the effectiveness and

efficiency of the use of DHT; the positive effects of

several available DHT are not finally proven, which

could be problematic (R5). They are still a too new

technology (e.g., DiGAs have only been available in

Germany since 2020), and there is not enough (long-

term) data available on the effect on individual

patients or their clinical pictures, and this effect may

only occur over a longer period or is generally not

easy to specify. The effort required for such a survey

is also considerable (R2). Nevertheless, the size of an

insurer is sometimes positively related to the

evaluability of DHT offerings. A larger user base at

least potentially facilitates evaluation because there

are likely to be more actual users in absolute terms.

This, in turn, may also have a slight advantage in

terms of attractiveness towards DHT providers, as the

insurer could more easily accompany an evaluation

(R6).

In general, prevention is a meaningful concern

where DHT can provide good and low-threshold

support so that, ultimately, patients can take better

care of themselves or their health with this additional

support (R2,6). Nevertheless, a higher burden on the

healthcare system can also arise here if the attention

of patients is increased for possibly non-critical health

aspects. All in all, the financial effects of preventive

measures or the evidence for them, at least in the short

term, is not entirely clear. But from the point of view

of care and medical science, more prevention

certainly makes sense in principle (R2,6).

Only in the case of DiGAs, it is the case that at

least an initial proof of benefit must be provided for

them to be officially listed by BfArM. However, they

can also be delisted if no effect or an undesirable

effect should occur in the longer term (R5,6).

It is true that a prescribed DiGA must also be paid

for. The success in introducing the DiGAs (there are

currently over 40 officially listed) is, on the one hand,

gratifying. However, with costs per application and

user averaging over 200 EUR, this also leads to new

financial burdens, whereas the savings effects have

yet to become apparent (potentially through

avoidance of doctor's visits and improved health in

general).

Another observed effect was that even with high-

quality DHT, a certain saturation effect occurs at

some point. If so, these solutions would have to be

improved and extended by further functionalities. Of

course, this then jeopardises cost-effectiveness and

makes it more difficult to prove usefulness due to

changed circumstances (R4).

3 CONCLUSIONS

The integration and adoption of DHT within the

healthcare landscape, especially from the perspective

of health insurers, is both promising and challenging.

The unanimous recognition of DHT's importance

underscores the potential of digitization in

revolutionizing healthcare. DHT promise to address

the challenges of an aging population, streamline

payment processes, enhance patient management,

especially for chronic diseases, and potentially reduce

healthcare costs. However, several challenges and

considerations emerge as a summary from the above:

Effectiveness and Efficiency: Despite the

potential benefits, there's a notable lack of

long-term data on the effectiveness and

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

876

efficiency of DHT. While some initial benefits

are observed, the long-term impact, especially

in terms of cost savings and clinical outcomes,

remains uncertain.

Adoption and Usage: The demographic target

group for DHT is not just the younger, tech-

savvy population. Middle-aged individuals

(40-60 years) present a significant user base,

given their health needs and growing digital

competence.

Regulation and Trust: While countries like

Germany have pioneered in creating a

regulatory framework for DHT, challenges like

trust, transparency, and interoperability persist.

Overregulation is a concern, but so is the need

for a framework that ensures the safety and

efficacy of these technologies.

Economic Implications: DHT present both an

opportunity for cost savings and a potential

financial burden. The balance between these

two outcomes is yet to be determined. The role

of health insurers in this equation, especially in

terms of reimbursement models and

partnerships with DHT providers, is pivotal. It

should also be noted, however, that hardly any

new business models have emerged so far. It is

rather the case that the topic of DHT arises

extrinsically, either to be able to meet the

supply situation better or to take regulations

into account (e.g., the introduction of DiGAs).

The non-mention of new business models is

thus also a recognition that, in case of doubt,

there is still potential for change here. In part,

there is still a rather restrained adoption, a very

gradual, partly small-scale engagement with

the topic.

Role of Health Insurers: Health insurers are

poised to play a significant role as gatekeepers,

ensuring the quality of DHT and potentially

driving their adoption. Their role in data

management, especially in leveraging patient

data for improved healthcare outcomes, is also

noteworthy.

Future Directions: As the DHT landscape

evolves, continuous evaluation and adaptation

are crucial. Technologies that fail to deliver

tangible benefits might need to be phased out

or improved. Furthermore, as the DHT

landscape becomes more saturated,

innovations will need to offer added

functionalities and address specific healthcare

challenges to remain relevant.

In summary, the present case study was able to

provide some relevant, exploratory insights into the

payer side’s perspective on DHT. Figure 1 provides a

summary of the given challenges.

Figure 1: Summary of the given challenges in the field of

DHT (This figure has been designed using images from

Flaticon.com).

Here, it should also be noted, however, that the

study cohort hardly showed any (national) differences

regarding the above-mentioned questions. There was

no major outlier in the responses, hardly any strongly

divergent opinion. On the one hand, this is due to the

relatively small size of the cohort, which, however, is

not critical in the sense of case study research. At the

same time, participation in the survey was not

controlled by the inviters (voluntary participation in

case of own interest). This resulted in a sample

distribution that was not known in advance and is

only of limited diversity. Accordingly, the potential

for future research results in a broader coverage of

more diverse aspects or healthcare systems or the

implementation of in-depth analyses for particularly

interesting aspects.

Overall, while DHT offer transformative potential

for the healthcare sector, their integration requires a

balanced approach, considering clinical outcomes,

economic implications, regulatory frameworks, and

the evolving needs of the patient population.

Collaboration among stakeholders, including health

insurers, DHT providers, regulators, and patients, will

be crucial in realizing the full potential of DHT.

Implications and Perceptions of Digital Health Technologies: A Multiple Case Study on the Payers’ Viewpoint

877

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants of the

survey, including the ones who did not want to be

individually mentioned or included as co-author here.

REFERENCES

Chaudhry, B., Wang, J., Wu, S., Maglione, M., Mojica, W.,

Roth, E., Morton, S. C., & Shekelle, P. G. (2006).

Systematic Review: Impact of Health Information

Technology on Quality, Efficiency, and Costs of

Medical Care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 144(10),

742–752.

Digital Therapeutics Alliance. (2023). Digital Health

Technology Ecosystem Categorization. https://dtxalli

ance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/DTA_FS_DHT-

Ecosystem-Categorization.pdf

European Commission. (2023a, September 27). European

Health Data Space. https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-

digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space_en

European Commission. (2023b, September 27). Medical

Devices—New regulations. https://health.ec.europa.eu/

medical-devices-new-regulations_en

European Commission. (2023c, October). Data

Governance Act explained—Shaping Europe’s digital

future. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/

data-governance-act-explained

Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. (2023a).

BfArM - Digital Health Applications (DiGA).

https://www.bfarm.de/EN/Medical-devices/Tasks/DiG

A-and-DiPA/Digital-Health-Applications/_node.html

Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. (2023b).

DiGA Registry—List of retired applications.

https://diga.bfarm.de/de/verzeichnis?type=%5B%22ret

ired%22%5D

Gand, K. (2017). Investigating on Requirements for

Business Model Representations—The Case of

Information Technology in Healthcare. Proceedings

IEEE 19th Conference on Business Informatics, 471–

480.

Katehakis, D. G., & Kouroubali, A. (2019). A framework

for eHealth interoperability management. Journal of

Strategic Innovation and Sustainability, 14(5), 51–61.

Mettler, T. (2016). Anticipating mismatches of HIT

investments: Developing a viability-fit model for e-

health services. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 85(1), 104–115.

Stroetmann, K. A., Kubitschke, L., Robinson, S.,

Stroetmann, V., Kullen, K., & McDaid, D. (2010). How

can telehealth help in the provision of integrated care?

(Health Systems and Policy Analysis - Policy Brief 13).

World Health Organization.

Suter, E., Oelke, N. D., Adair, C. E., & Armitage, G. D.

(2009). Ten Key Principles for Successful Health

Systems Integration. Healthcare Quarterly, 13(Spec

No), 16–23.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2021).

Ageing in the digital era – UNECE highlights key

actions to ensure digital inclusion of older persons.

https://unece.org/media/press/358156

Vandenberghe, D., & Albrecht, J. (2020). The financial

burden of non-communicable diseases in the European

Union: A systematic review. European Journal of

Public Health, 30(4), 833–839.

Veit, D., Clemons, E., Benlian, A., Buxmann, P., Hess, T.,

Kundisch, D., Leimeister, M., Loos, P., & Spann, M.

(2014). Business Models. Business & Information

Systems Engineering, 6(1), 45–53.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case Study Research – Design and

Methods. Sage Publications.

APPENDIX

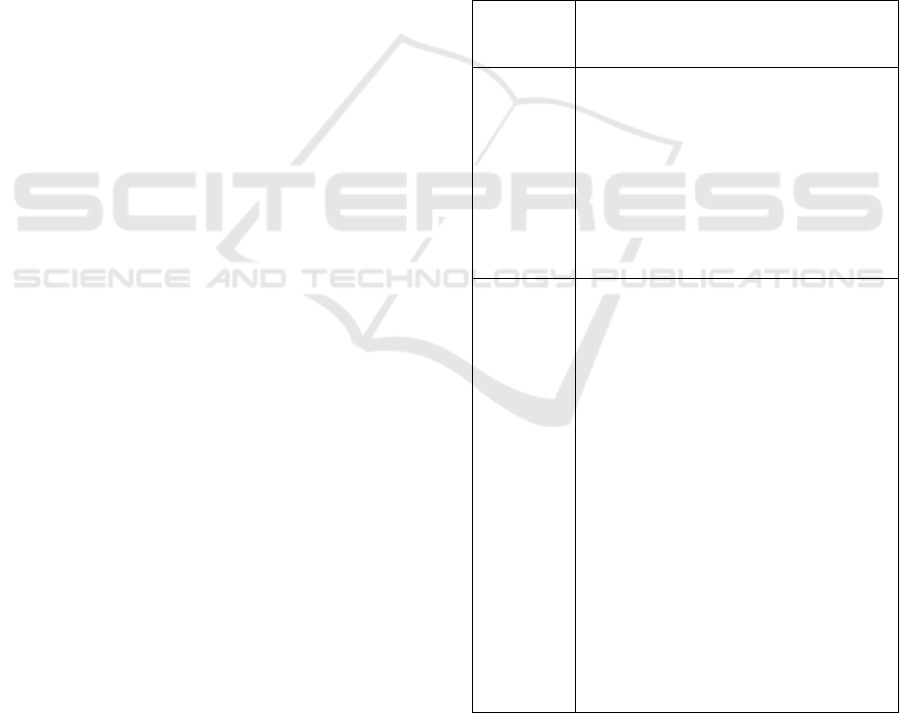

Table 4: Details on the mode of the survey.

Mode of

the survey

Details

Online

survey

(N=5;

for R1-R5)

A LimeSurvey instance by the main

authors’ institution has been used with

the elements as displayed in Table 1

The link to the survey has been sent

via the Europe-wide network of the

authors to contact representatives of

the payer or insurer side in the health

care system. A reminder was sent out

two weeks later.

Guideline-

based in-

person

interview

(N=1;

for R6)

The elements in Table 1 have served as

a guideline for the interview.

Not every single element was gone

through step by step. On the one hand,

the flow of the conversation should not

be interrupted unnecessarily. On the

other hand, partial aspects of some

questions were already addressed in a

previous answer, so that all relevant

aspects were nevertheless covered.

The conversation lasted about 1 hour.

Two people took part on both the

respondent and interviewer sides. This

ensured a good match with the survey

objectives.

A written summary of the interview

has been created based on the notes

taken during the interview.

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

878