Evaluation of Approximate Reflectional Symmetry

Martin Ma

ˇ

n

´

ak

1 a

, David Podgorelec

2 b

and Ivana Kolingerov

´

a

3 c

1

New Technologies for the Information Society (NTIS), University of West Bohemia,

Univerzitn

´

ı 8, 301 00 Pilsen, Czech Republic

2

Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of Maribor,

Koro

ˇ

ska cesta 46, SI-2000 Maribor, Slovenia

3

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Faculty of Applied Sciences, University of West Bohemia,

Univerzitn

´

ı 8, 301 00 Pilsen, Czech Republic

Keywords:

Symmetry, Approximate, Visualization, Evaluation.

Abstract:

When an object can be split by a plane into two symmetrical parts, one being the mirrored image of the other,

the object has a reflectional symmetry with respect to that plane. The symmetry is often only approximate and

not necessarily global. Many algorithms exist for the detection of symmetries and there are various applica-

tions utilizing symmetrical properties. Yet there are not so many ways to measure the amount of approximate

reflectional symmetry. In this paper, we introduce a method for the evaluation of approximate symmetry for

objects represented as a point cloud. The method consists of three parts - a relative symmetry distance for

measuring the amount of approximate reflectional symmetry, a plot of relative errors, and visualization of

errors. This method offers a way how to compare different objects by the amount of symmetry and improves

understanding of the symmetrical properties of objects, both quantitatively and visually.

1 INTRODUCTION

Symmetry is an important property of many real-

world objects as well as artificially created objects.

An object is symmetrical, if there is a transformation

(distance preserving, except identity) that maps the

object onto itself, hence the object is invariant under

the transformation. A typical example is reflectional

symmetry when an object can be split into two parts

perfectly mirrored by a plane. However, real-world

objects are hardly ever perfectly symmetrical. Even

if an object can be perceived as symmetrical, it can

have minor variations and imperfections, some parts

may be missing, etc. The symmetry can still be rec-

ognized but it is only an approximate symmetry.

Many methods for the detection of approximate

symmetries exist. In our work, we use robust, fast and

flexible symmetry plane detection based on differen-

tiable symmetry measure by (Hruda et al., 2022b).

For an object in a point cloud representation, we can

hence obtain one or more planes of its reflectional

symmetries.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1248-7042

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0701-9201

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4556-2771

The most important part of Hruda’s symmetry de-

tection method is a function for symmetry measure-

ment. It is a function evaluating the given object and

a plane of reflectional symmetry. Finding the best

plane is then done as locating the maxima of this

function in transformation space. The contribution

of each reflected point to the overall amount of sym-

metry is computed by summing up the distances to

neighboring points. It is a weighted sum, where more

distant points get lower weights than closer points.

Wendland’s function is used instead of Gaussian for

weights because it has limited support and is differ-

entiable. The final value of the symmetry measure

depends on the number of points, Wendland’s func-

tion support radius, and the local density of points.

These parameters are constant for a single object but

they may be different for others. Therefore, Hruda’s

symmetry measure is not well suited for comparing

multiple objects.

The problem addressed by this paper is how to

measure the quality of the detected symmetry. If we

detect approximate symmetries in several mutually

different objects, we want to distinguish more sym-

metrical objects from the less symmetrical ones. We

propose a new relative symmetry distance for measur-

ing the amount of reflectional symmetry of an object

734

Ma

ˇ

nák, M., Podgorelec, D. and Kolingerová, I.

Evaluation of Approximate Reflectional Symmetry.

DOI: 10.5220/0012472800003660

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 19th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2024) - Volume 1: GRAPP, HUCAPP

and IVAPP, pages 734-740

ISBN: 978-989-758-679-8; ISSN: 2184-4321

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

and for the comparison of different objects. The dis-

tance is based on relative errors. It is invariant to the

rotation, translation and scale of the input object. Fur-

thermore, we introduce an error plot and a coloring

scheme, which help to understand the symmetrical

content of the object both quantitatively and visually.

The proposed method is demonstrated in a few ex-

amples and compared against Hruda’s differentiable

symmetry measure.

2 RELATED WORK

Symmetry has been studied extensively from many

perspectives, e.g., psychological (Bertamini et al.,

2018), mathematical (Bizzarri et al., 2022), compu-

tational, possible applications, etc. Many different

methods for the detection of reflectional symmetries

(and also other types of symmetry) have already been

developed, e.g. PRST transform by (Podolak et al.,

2006), a few methods by (Mitra et al., 2006) (Mi-

tra et al., 2013), including an interesting application

(symmetrization) for transforming otherwise asym-

metric shapes to their initial symmetric poses by (Mi-

tra et al., 2007), or the method by (Hruda et al.,

2022b) using a differentiable symmetry measure. Re-

cently, (Hruda et al., 2022a) presented an idea for the

detection of rotational symmetry, using two reflec-

tional symmetry planes.

Regarding approximate symmetry evaluation,

there are a few options. An object A and its trans-

formed image B = T (A) could be compared for sim-

ilarity using standard statistical measures, e.g., inter-

section over union

J(A,B) =

|A ∩ B|

|A ∪ B|

(1)

(also known as the Jacard/Tanimoto coefficients).

However, this approach would require objects with

closed boundaries. Another option is to use Hausdorff

distance. Although this distance is very sensitive to

outliers, a solution exists (Maiseli, 2021). Neverthe-

less, missing or extruding object parts are the problem

with approximate symmetry, not single-point outliers.

Perhaps more suitable is the Metro tool

by (Cignoni et al., 1998). This tool was devel-

oped for measuring the error for meshes and their

simplifications, e.g., multiple levels of detail. It

outputs, among other characteristics, the mean error

and the maximal error between two surfaces (one of

them is sampled and the sample-to-surface distances

are computed for each sample). The mean error

is computed as the error distance integral over the

whole surface divided by the surface area. These two

surfaces would correspond to our object A and its im-

age B. The maximal error is the Hausdorff distance.

This tool has been used successfully by (Hruda et al.,

2022b) for evaluating the symmetry planes from their

symmetry detection framework against a view-based

symmetry detection approach by (Li et al., 2016) and

against a clustering-based approach by Shi et al. (Shi

et al., 2016). Besides absolute errors, Metro also

outputs relative errors expressed as the percentage of

the bounding box diagonal. However, the bounding

box diagonal is a global characteristic sensitive to

the overall shape of the object. Therefore, we do not

consider it so much suitable for the evaluation of

approximate symmetry. Unless, of course, the object

fits tightly to its bounding box.

There also is the symmetry distance proposed

by (Zabrodsky et al., 1993). The idea is that symme-

try should be treated as a continuous measure rather

than a binary decision (symmetric/asymmetric). They

suggest measuring the minimum effort necessary to

turn a shape into a symmetric shape. This effort is

measured as the sum of squared distances moved by

points of the shape, i.e.,

SD =

1

n

n−1

∑

i=0

||P

i

−

ˆ

P

i

||

2

, (2)

where P

i

is a point of the shape P and

ˆ

P the symmetry

transform. The distance is invariant to rotation and

translation. Invariance to scale is provided by scaling

the object so that the maximum distance from the ob-

ject centroid is constant. As we already mentioned,

such scaling can be very sensitive to outliers and ex-

truding object parts.

Coloring objects for the visualization of symme-

try plane and surface errors is not new. He et al. (He

et al., 2020) use a technique similar to ours for high-

lighting object parts in the corresponding symme-

try half-spaces. A heat map is used in the Metro

tool (Cignoni et al., 1998) to visualize errors. This

is a common technique, nevertheless, we consider our

coloring scheme worth including because it clearly il-

lustrates the development of approximate symmetry

on a given object.

Sometimes, coloring can be used just as a hint

where symmetry occurs locally. The symmetry de-

tection method by (Podgorelec et al., 2023) is spe-

cialized for Earth observation data. The acquisition

of such data (e.g. LiDAR) cannot provide exact pairs

of symmetric elements and, therefore, the method is

strictly focused on approximate symmetries, which is

accomplished by voxelization. The algorithm detects

all partial symmetries for a chosen voxel resolution,

identifies local and global symmetries among them,

and measures the amount of each individual symme-

Evaluation of Approximate Reflectional Symmetry

735

try within the entire input dataset. The method does

not evaluate approximate symmetry explicitly, but it

gives the obvious hint that in partial or local symme-

try, it is sufficient to consider the points contained in

the voxels of symmetric pairs.

3 PROPOSED METHOD

Here we present our method for the evaluation of ap-

proximate reflectional symmetry of objects with re-

spect to their symmetry planes. The input to our

method is an object represented as a point cloud.

If no symmetry plane is given, it will be computed

by (Hruda et al., 2022b) method. The output consists

of quantitative and visual characteristics, suitable for

inter-object comparisons and evaluation. The key as-

pects are discussed in the following subsections.

3.1 Relative Symmetry Error

Let p be any point of the input object and R be the

given plane of reflective symmetry. The symmetry

transforms p to its image p

′

. Since the object may

be only approximately symmetrical, p

′

will not nec-

essarily be part of the input object but it may be close.

We take the closest point of the input object (from the

same side of R where also p

′

lies) as the best sym-

metrical counterpart of p. Since the input object is a

point cloud, the closest point is the nearest neighbor

of p

′

as measured by the Euclidean distance from p

′

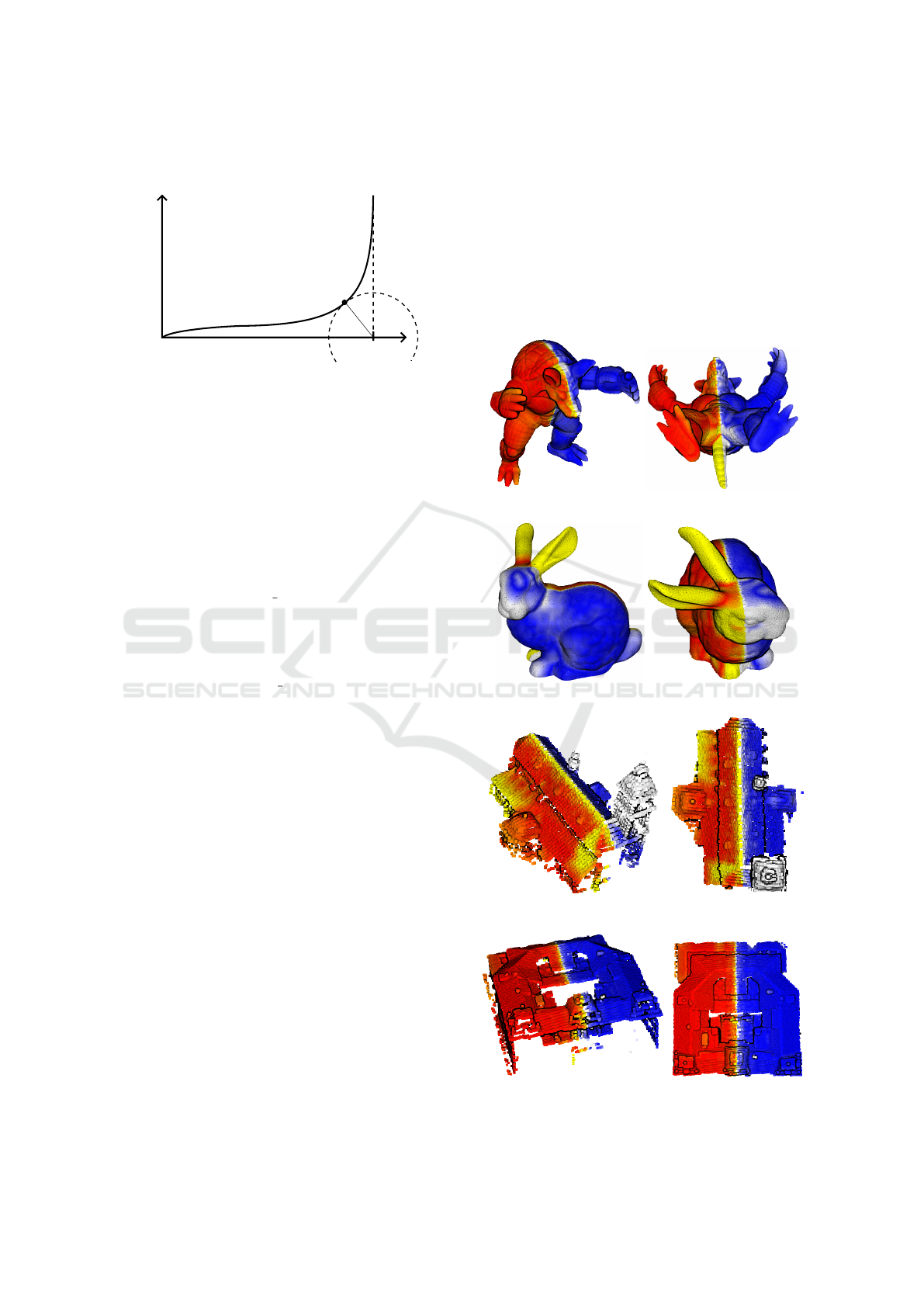

as depicted in Figure 1. The error is measured as

E

relative

=

d

2

d

1

, (3)

where d

1

is the Euclidean distance of p

′

from p and d

2

is the Euclidean distance of nn(p

′

) from p

′

. The er-

ror is relative. If we consider a tolerance threshold,

e.g., 5%, small symmetry transformation distances

(d

1

) would have a small absolute tolerance and larger

transformation distances will have larger absolute tol-

erances.

To quickly find the nearest neighbor of a point,

we utilize the R-tree spatial index (Guttman, 1984)

from the C++ Boost Geometry Library with the av-

erage time complexity O(log n) per query. Other in-

dexing structures could be used as well, e.g., a spatial

grid, a k-d tree, an octree, etc.

3.2 Symmetry Error Plot for all Points

Inspecting the relative error at each point individually

would not provide much information about the sym-

metry of the whole object. We need to look at these

p

nn(p')

p'

R

d

1

/2

d

2

d

1

Figure 1: The relative error for the point p is the fraction

d

2

/d

1

. Here, nn(p’) is the nearest neighbor of p’, the sym-

metric image of p, found in the half-space containing p’.

pieces of information together. Therefore, we first

sort the points by their relative errors in ascending or-

der. Then we consider a 2-dimensional error plot as

illustrated in Figure 2, where the x-axis represents the

sorted points in the normalized range < 0,1 > and the

y-axis represents their relative errors.

If the whole object was perfectly symmetrical, the

vast majority of values in the error plot would be zero.

In reality, they will be almost zero, shifted a little bit

in the positive direction of the y-axis, because of the

point cloud representation of the object and the in-

herent discrete sampling. Even for an approximately

symmetrical object, the vast majority of values in the

error plot will be close to some tolerance threshold

(a constant on the y-axis) distinguishing symmetry

from asymmetry. However, it can be tricky to set a

specific (low enough) tolerance threshold beforehand,

because the object may only be partially symmetric.

3.3 The Symmetry Threshold Point

The error plot of a strongly symmetrical object will

resemble the vertically mirrored letter L as illustrated

in Figure 2. We define the symmetry tolerance thresh-

old point T = (T

x

,T

y

) as the point of the error plot

minimizing the Euclidean distance from the lower

right corner (1,0) and measure the distance

d =

q

(1 − T

x

)

2

+ T

2

y

(4)

to characterize the overall amount of approximate

symmetry of a given object. The more symmetrical

the object is, the more its error plot approaches the

x-axis, T approaches (1, 0), and d approaches zero.

Only the points to the left of T

x

in the error plot are

symmetrical with relative errors up to T

y

. The dis-

tance d combines both these quantities into one. It

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

736

also gives us an initial guess that at least 1 − d of the

whole object is within the error limit d.

0 1

x: points

y: relative error

T

Figure 2: The error plot and the threshold point T.

3.4 Visualization

We use a coloring scheme, where points on the op-

posite sides of the symmetry plane have two different

basic colors, e.g., red and blue. These basic colors

are then linearly interpolated to colors highlighting

the relative symmetry error, e.g., yellow and white.

If we want to emphasize relative errors in a certain

range, e.g., up to 20%, we will set the interpolation

factor

f = min(rel error/0.2, 1). (5)

However, this range may be too generous for strongly

symmetric models or too strict for weakly symmetric

models. In such situations, we can set

f = min(rel error/T

y

,1) (6)

and the whole interpolation range will be dedicated to

points that are considered symmetric with respect to

the automatically detected threshold point T .

4 EXPERIMENTS AND RESULTS

The general applicability and properties of the pro-

posed symmetry evaluation approach are demon-

strated on a few models - the Stanford Armadillo and

Bunny (Levoy et al., 2005), two historical buildings,

namely the Maribor Cathedral and the University of

Maribor at GPS location 46.5592, 15.6442 (

ˇ

Zalik,

2023), a statue and a component, both coming from

the Thingi10K dataset (Zhou and Jacobson, 2016).

Armadillo, Bunny and the statue are two examples of

bilaterally symmetrical beings in more or less asym-

metrical poses. Approximate symmetry in the two

buildings and the component is present due to archi-

tectural or constructional intents. Whereas the point

clouds of Armadillo, Bunny, the statue, and the com-

ponent were obtained artificially by sampling the tri-

angular meshes, the point clouds of buildings come

from aerial LiDAR scanning and hence they may have

some imperfections, e.g., under-sampled or missing

vertical regions, irregular sampling, noise, etc.

For all these models, we detected the major sym-

metry plane using (Hruda et al., 2022b) symmetry de-

tection framework, computed the corresponding error

plots, found the symmetry threshold point T and its

relative symmetry distance d, and colored the point

clouds with respect to the detected plane and errors.

The results are depicted in Figures 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Figure 3: Armadillo - relative symmetry distance d = 0.132.

Figure 4: Bunny - relative symmetry distance d = 0.267.

Figure 5: Cathedral - relative symmetry distance d = 0.273.

Figure 6: University - relative symmetry distance 0.098.

Evaluation of Approximate Reflectional Symmetry

737

Figure 7: Statue - d = 0.370; Component - d = 0.111.

When these objects are sorted by the proposed rel-

ative symmetry distance, the most symmetric object is

the university building (0.098), followed by the com-

ponent (0.111), Armadillo (0.132), Bunny (0.267),

the cathedral (0.273), and the statue (0.370). Red

and blue regions indicate strongly symmetric regions,

whereas strictly yellow and white regions indicate rel-

ative errors of 0.2 (20%) or more. The visualization

shows that Armadillo is in a symmetric pose with a

slight asymmetry of arms, fingers and tail. Bunny is in

a more asymmetric pose with a slightly rotated head

and ears and these body parts are relatively larger

when compared against Armadillo. The symmetry of

the cathedral is violated by its main tower, a smaller

tower, and a side roof. The symmetry of the statue

is dominated by the rounded pedestal and ruined by

the rotated torso and body parts. The symmetry of the

component seems to be almost perfect. Its nonzero

relative symmetry distance can be attributed to a rela-

tively low sampling density and a slightly higher per-

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

Bunny

Armadillo

Cathedral

University

Statue

Component

points

relative error

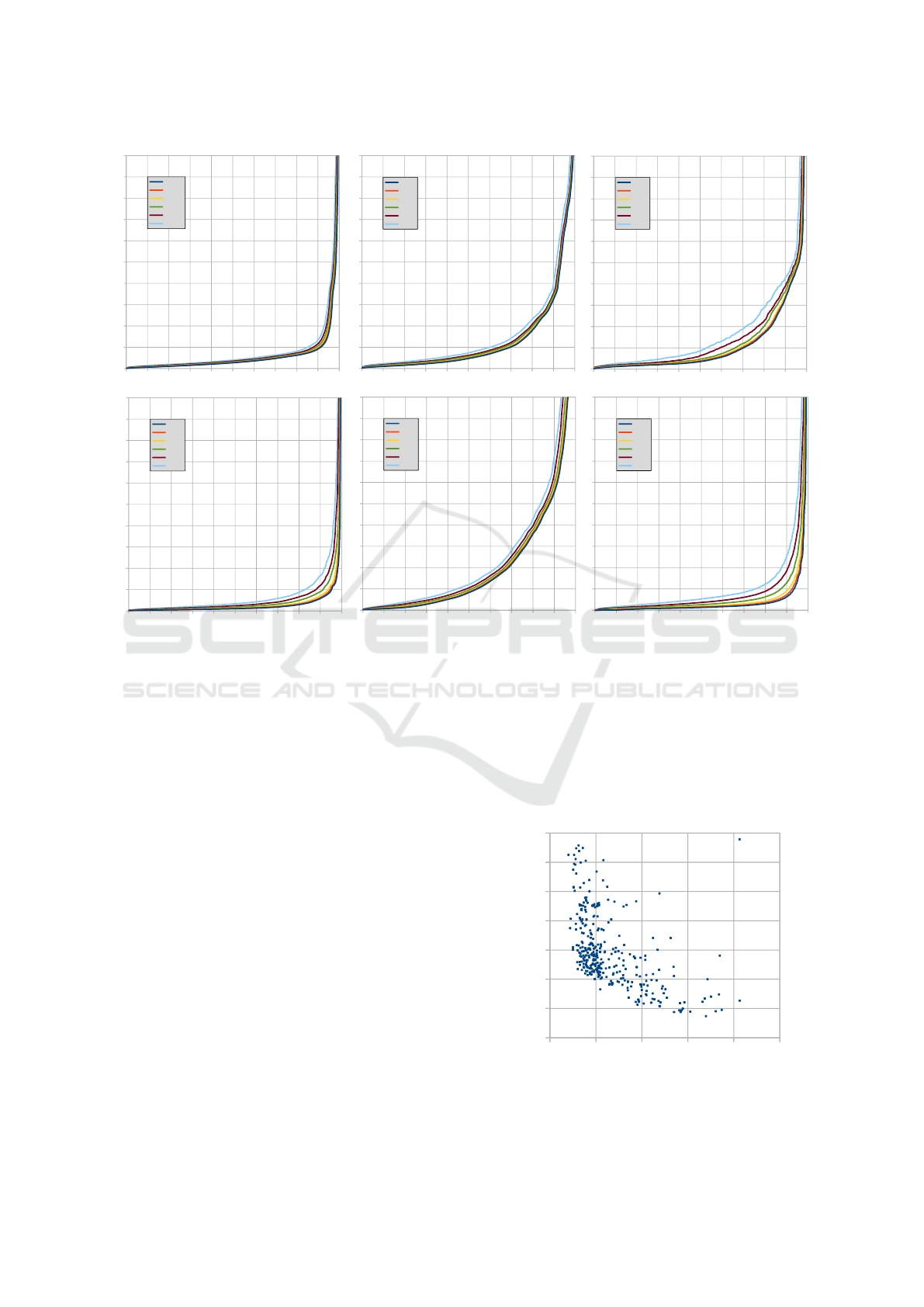

Figure 8: Error plots for the tested models.

centage of points near the symmetry plane. The cor-

responding error plots of these objects are depicted in

Figure 8 together with the threshold points and their

attraction line to the ideal point < 1,0 >.

Visualization also shows that points near the sym-

metry plane usually have a large relative error despite

their absolute error may be small. Sampling irregu-

larity can play some role here but it is more likely

that the detected symmetry plane cannot fully reflect

all the small violations of symmetry, e.g., Armadillo’s

tail and muzzle in Figure 3 are slightly off the detected

plane but the plane is globally better for many more

other points. The effect of such symmetry imperfec-

tions on the relative error gets stronger near the sym-

metry plane.

Coloring with thresholds can also be used for

more visual highlighting of the symmetry error propa-

gation as illustrated in Figure 9. Using a single thresh-

old, even the automatically detected one, would make

the symmetry error propagation almost invisible. As

the threshold is being moved to lower values, the most

symmetric parts of the model will remain in red and

blue colors whereas the less symmetric parts of the

model will be in yellow and white colors. We can in-

terpret, e.g., that Armadillo’s forearms are in a quite

symmetric pose, with the right palm shifted up a lit-

tle bit against the left palm (by one or two fingers).

The error in most of the points on the palms is within

2% − %5 of the palm-to-palm distance.

Sampling density naturally has some influence on

(a) (b)

(c) (d)

Figure 9: Armadillo colored with different thresholds shows

the development of relative symmetry error. Thresholds:

(a) 0.10 - found automatically from T; (b) 0.08; (c) 0.05;

(d) 0.02.

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

738

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

172974

128899

85516

42553

21489

10409

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

99879

74447

49383

21967

12396

6001

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

11779

8838

5846

2946

1481

735

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

32909

24602

16335

8148

4116

1997

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

90069

67202

44606

22188

11218

5430

Armadillo Cathedral

Statue

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

90042

67185

44595

22182

11214

5426

Bunny

University Component

Samples count

Samples count

Samples count

Samples count

Samples count

Samples count

Figure 10: The behavior of relative symmetry error plots when they are computed on 100%, 75%, 50%, 25%, 12.5%, and 6%

random samples taken from the same model. Decreasing the sampling density increases the relative symmetry error.

the shape of symmetry error plots and hence also on

relative symmetry distances. If the number of samples

on the surface of an object is reduced, nearest neigh-

bor distances will generally increase and the error plot

will lift up. This is illustrated in Figure 10, where

we reduced the sampling of tested models to 75%,

50%, 25%, 12, 5%, and 6% of the original amount of

points. The symmetry plane was detected only once

for each model (using 100% samples). Although the

error plots may seem to change only marginally for

some models, we can clearly see that the comparison

based on the value of d can be influenced by sampling

densities. For example, the university with 75% of

samples will be evaluated as being more symmetrical

than the component with 12.5% of samples:

d(Uni,75%) = 0.11 < d(Comp,12.5%) = 0.19. (7)

On the other hand, the university with only 12.5% of

samples will be evaluated less symmetrical than the

component with 75% of samples:

d(Uni,12.5%) = 0.15 > d(Comp,75%) = 0.12. (8)

Therefore, judgements based on the relative symme-

try distance of different objects of unknown sampling

densities should be made with caution.

In the next experiment, we compared the proposed

relative symmetry distance against Hruda’s measure

of symmetry on a subset of the Thingi10K dataset.

We selected over 350 models having 90 000-110 000

samples each. Results are depicted in Figure 11.

Each point in the plot represents one model from the

Thingi10K dataset. The proposed relative symmetry

distance does not correlate much with Hruda’s mea-

0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

symmetry distance d

Hruda's measure

Figure 11: Relative symmetry distance d against Hruda’s

measure on a subset of the Thingi10K dataset.

Evaluation of Approximate Reflectional Symmetry

739

sure. The correlation coefficient is −0.3974 and it

did not change substantially (−0.3939) even when

Hruda’s measure was normalized by dividing the

value by the number of input points.

Interestingly, Hruda’s measure for the statue (with

90 069 points) is 1390.355; and for the component

(with 90 042 points) it is 1454.743. The similarity of

these two values supports the observation that Hruda’s

measure is not very suitable for comparing the sym-

metry of different objects. The relative symmetry dis-

tance d, however, may also have its limits, as can

be seen in Figure 8 (similar values for the cathedral

and Bunny). Therefore, instead of using d as a sin-

gle value for comparison, it may be worth using some

supplementary information from the error plot, e.g.,

the relative amount of points at several relative error

levels, e.g., at 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15 and 0.20.

Getting more points at low error levels will then in-

dicate the error plot approaches to zero, i.e., a better

symmetry.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The proposed method is usable for comparing ob-

jects (point clouds) by the amount of approximate

reflectional symmetry if the symmetry plane is pro-

vided or computed. The idea of measuring errors rel-

atively makes this method invariant with respect to

the global object scale, e.g., the bounding box diag-

onal. If a global normalization was used instead, the

results would be sensitive to the overall shape of the

object due to extruding or missing parts. Low values

of the proposed relative symmetry distance d, e.g., in

the range < 0, 0.15 >, mean that a high percentage

of points have their symmetrical counterpart with low

relative errors. Higher values, e.g., d > 0.2, mean that

the symmetry is more seriously violated. To better un-

derstand the cause, it may be worth further analyzing

the error plot or seeing the visualization of errors on

the object. Values of d > 0.5 are very high because the

symmetrical counterpart could lie in the same half-

space with a non-zero probability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Czech Science

Foundation, project number 21-08009K, and by the

Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency under re-

search project N2-0181 and Research Programme P2-

0041.

REFERENCES

Bertamini, M., Silvanto, J., Norcia, A. M., Makin, A. D.,

and Wagemans, J. (2018). The neural basis of visual

symmetry and its role in mid- and high-level visual

processing. Annals of the New York Academy of Sci-

ences, 1426(1):111–126.

Bizzarri, M., L

´

avi

ˇ

cka, and Vr

ˇ

sek, J. (2022). Approximate

symmetries of perturbed planar discrete curves. Com-

puter Aided Geometric Design, 96:102115.

Cignoni, P., Rocchini, C., and Scopigno, R. (1998). Metro:

Measuring error on simplified surfaces. Computer

Graphics Forum, 17(2):167–174.

Guttman, A. (1984). R-Trees: A dynamic index structure

for spatial searching. SIGMOD Record, 14(2):47–57.

He, C., Wang, L., Zhang, Y., and Wang, C. (2020). Dom-

inant symmetry plane detection for point-based 3D

models. Advances in Multimedia, 2020:1–8.

Hruda, L., Kolingerov

´

a, I., L

´

avi

ˇ

cka, M., and Ma

ˇ

n

´

ak, M.

(2022a). Rotational symmetry detection in 3D us-

ing reflectional symmetry candidates and quaternion-

based rotation parameterization. Computer Aided Ge-

ometric Design, 98:102138.

Hruda, L., Kolingerov

´

a, I., and V

´

a

ˇ

sa, L. (2022b). Robust,

fast and flexible symmetry plane detection based on

differentiable symmetry measure. Visual Computer,

38(2):555–571.

Levoy, M., Gerth, J., Curless, B., and Pull, K. (2005).

The Stanford 3D scanning repository. http://www.

graphics.stanford.edu/data/3Dscanrep/.

Li, B., Johan, H., Ye, Y., and Lu, Y. (2016). Efficient 3d re-

flection symmetry detection: A view-based approach.

Graph. Model., 83:2–14.

Maiseli, B. J. (2021). Hausdorff distance with outliers and

noise resilience capabilities. SN Computer Science,

2(5):358.

Mitra, N. J., Guibas, L., and Pauly, M. (2007). Symmetriza-

tion. ACM Transactions on Graphics (SIGGRAPH),

26(3):#63, 1–8.

Mitra, N. J., Guibas, L. J., and Pauly, M. (2006). Partial

and approximate symmetry detection for 3D geome-

try. ACM Trans. Graph., 25(3):560–568.

Mitra, N. J., Pauly, M., Wand, M., and Ceylan, D. (2013).

Symmetry in 3D geometry: Extraction and applica-

tions. Computer Graphics Forum, 32(6):1–23.

Podgorelec, D., Luka

ˇ

c, L., and

ˇ

Zalik, B. (2023). Reflection

symmetry detection in Earth observation data. Sen-

sors, 23(17).

Podolak, J., Shilane, P., Golovinskiy, A., Rusinkiewicz, S.,

and Funkhouser, T. (2006). A planar-reflective sym-

metry transform for 3D shapes. ACM Transactions on

Graphics (Proc. SIGGRAPH), 25(3).

Shi, Z., Alliez, P., Desbrun, M., Bao, H., and Huang, J.

(2016). Symmetry and orbit detection via lie-algebra

voting. Computer Graphics Forum, 35(5):217–227.

ˇ

Zalik, B. (2023). The GeMMA laboratory. https://gemma.

feri.um.si/.

Zabrodsky, H., Peleg, S., and Avnir, D. (1993). Completion

of occluded shapes using symmetry. In Proceedings

of IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern

Recognition, pages 678–679.

Zhou, Q. and Jacobson, A. (2016). Thingi10k: A dataset of

10, 000 3D-printing models. CoRR, abs/1605.04797.

arXiv preprint.

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

740