Managing Adverse Commentary on Social Media: A Case Study of an

Australian Health Organisation

Gitte Galea

1a

, Ritesh Chugh

2b

and Lydia Mainey

3c

1

School of Engineering and Technology, Central Queensland University, Cairns, Australia

2

School of Engineering and Technology, Central Queensland University, Melbourne, Australia

3

School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Sciences, Central Queensland University, Cairns, Australia

Keywords: Health Communication, Social Media, Organisational Process, Health, Healthcare, Grounded Theory,

Australia.

Abstract: Health communication on social media is complicated, challenging, and multi-dimensional. Globally, the

evolution of health communication has transformed rapidly from one-way to two-way interaction, with

diverse audiences expressing limitless and often unconstrained commentary based on individual beliefs. This

paper, a segment of a comprehensive doctoral study into the adoption and utilisation of social media within a

large Australian health organisation, specifically Queensland Health, offers a snapshot of the research findings

for managing negative commentary. This novel study interviewed social media administrators to understand

their experiences and perceptions of social media use, underscoring the prominence of negative commentary

as a notable drawback to the effective use of social media. Paradoxically, such adverse commentary also

catalyses discussions and leads to helpful feedback. Effectively managing unacceptable commentary

necessitates the implementation of a strategic response complemented by adequate resources and training.

1 INTRODUCTION

Social media is ubiquitous in our society and is an

appealing channel for health organisations to

communicate information quickly and effectively.

However, social media is a powerful, evolving tool

that is not well understood (Kelly et al., 2019). The

capabilities of social media and its importance are

continually changing (Jami Pour & Jafari, 2019).

While social media research studies have increased,

there is limited research on how health organisations

manage and leverage the use of social media (Chen

and Wang, 2021), particularly in an Australian

context. Hunt (2022) suggests a framework for social

media-based public health campaigns and called for

public health agencies to continue to optimise and

rigorously evaluate the use of social media for health

promotion. However, the use of social media in health

is not limited to health promotion, which can often be

only one-way communication. The transformation to

two-way communication has created additional

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2674-2531

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0061-7206

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1438-8061

processes and administrative burdens. Moreover, the

COVID-19 pandemic provided the ultimate stress test

for social media in health and expedited the need for

more resources to manage social media.

Batra (2023) supports the notion that health

professionals should engage with the audience with

correct information and dispel false information from

spreading to the masses. However, Batra’s (2023)

framework centres on health professionals as indivi-

duals, and a gap still exists for health organisations.

In their investigation involving interviews with

health professionals in Australia, Lupton and Michael

(2017) unearthed a prevailing oversight— the failure

to acknowledge that social media transcends being a

mere one-way conduit for disseminating educational

messages. This lack of recognition of how social

media can be used as a two-way communication tool

creates challenges in managing commentary.

Previous studies on the use of social media in health

reveal that misinformation on social media is

prevalent worldwide and tends to be more popular

Galea, G., Chugh, R. and Mainey, L.

Managing Adverse Commentary on Social Media: A Case Study of an Australian Health Organisation.

DOI: 10.5220/0012552800003690

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterpr ise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024) - Volume 2, pages 443-448

ISBN: 978-989-758-692-7; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

443

than accurate information (Wang et al., 2019). For

example, communication staff in health-associated

organisations in Australia described social media

commentary by anti-vaccine activists as hostile and

likened it to a conflict zone, inducing fear and anxiety

(Steffens et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019).

A review of the literature revealed that studying

negative commentary is an under-researched social

media phenomenon (Labrecque et al., 2022).

Labrecque (2022) found that negative comments can

increase engagement through sharing, commenting,

and following. However, many organisations view

the potential harm from negative commentary as a

drawback. Starbucks considered removing its

Facebook page in 2021 when it struggled to moderate

negative commentary and was unable to disable

comments on its page (Mac, 2021). Moreover, it is

not feasible to identify and respond to every negative

comment (Labrecque et al., 2022). Guidelines for

online recruitment via social media advise deleting

negative commentary that may cause reputational

harm, but in a study by Waling (2022) they chose a

case-by-case approach to manage negative

commentary. Organisations should not be quick to

remove negative commentary or fail to correct

misinformation (BVA News, 2014; Labrecque et al.,

2022), but focusing on how they respond is important

(Javornik et al., 2020). Organisations need to design

a response strategy and communication style (Johnen

& Schnittka, 2019) and assess the tone of

commentary (Labrecque et al., 2022). Moreover,

teams that respond to social media should adopt a

tone that reflects the organisation to minimise

reputational damage (Johnen & Schnittka, 2019;

Labrecque et al., 2022). Demsar (2021) provides a

comprehensive understanding of trolling and

suggests preventative measures such as ongoing

monitoring, social media policy changes, amending

terms and conditions and a response strategy.

Managing negative commentary is not a one-size-fits-

all approach, and there is a lack of research on

managing negative commentary on social media in

health organisations. Therefore, the research question

in this study is, how does Queensland Health, an

Australian health organisation, manage negative

commentary on social media?

This paper is part of a doctoral study exploring the

adoption and use of social media in Queensland

Health. Queensland Health is a large state

government Australian health organisation that

comprises 16 Hospital and Health Services (HHSs)

and one Department of Health (Queensland) (DOH)

The resident population of Queensland is 5.5 million

people (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2023), and

the total land area is 1,729,742 km2 (Australian

Government, 2021). Australia has over 26 million

people (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2023), and

Queensland Health represents one-fifth of health

organisations in Australia. Nineteen semi-structured

interviews were conducted in this study with

Queensland Health employees who administer or are

accountable for official social media channels. This

study is representative of the use of social media in

Queensland Health. While the findings could be

generalisable to other health organisations in

Australia and globally, caution is recommended.

2 METHODOLOGICAL

APPROACH

The study employed a constructivist grounded theory

(CGT) approach (Charmaz, 2014). CGT is

appropriate for exploring human processes and

allows for the co-construction of theory between the

researcher and the participants (Charmaz, 2017). The

researchers place significant importance on this

perspective of human interaction, as they firmly

believe that the acquisition of novel knowledge

regarding various processes stems directly from the

firsthand experiences of participants and the

researchers’ subsequent interpretation of these

experiences.

Table 1: Participant roles held with Queensland Health

Hospital and Health Services.

Participant Participant Role

001 Mana

g

er Communications

002 Director Communications

003 Director Communications

004 Director Communications

005 Social Media Adviso

r

006 Senior Media Office

r

007 Communications Office

r

008 Mana

g

er Di

g

ital En

g

a

g

ement

009 Media Office

r

010 Communications Office

r

011 Senior Communications Office

r

012 Communications Office

r

013 Communications Office

r

014 Communications Office

r

015 Director Communications

016 Principal Media & Communications

Adviso

r

017 Manager Public Affairs

018 Social and Digital Media Team Leade

r

019 Manager Public Relations

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

444

Interviews were chosen as the primary source for

data generation. This study’s sample (n=19) was

purposive (Creswell, 2013), interviewing Queensland

Health employees who administer or are accountable

for social media.

Queensland Health employs a decentralised

management model, with each HHS operating

autonomously. This study involved a diverse mix of

participants, including both senior management and

operational staff, as detailed in Table 1.

A secondary source included internal Queensland

Health policy and guideline documents obtained post-

interview, supporting and expanding on concepts

identified from the interviews.

Coding took place using NVivo, a qualitative

analysis tool, and the techniques of line-by-line

coding and in vivo coding, followed by focused

coding, were used. Analysis was conducted

simultaneously with coding the data, using an

inductive approach. Concepts that were repeated

formed categories, and “managing negative

commentary” emerged as a minor category. Each

interview was compared to former interviews through

the process of constant comparison to form core

categories, and “managing commentary” emerged as

the major category linked to “managing negative

commentary”. The major category formed the

building blocks of theory and core category

development. Theoretical sampling was met through

in-depth interviewing techniques to explore the

concept of negative commentary further in each

subsequent interview. Memos were used for each

interview and constantly compared and updated for

theoretical refinement.

3 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Participants explained that managing negative

commentary on social media is complicated and

requires a human to judge the tone and possible

consequences and to choose an appropriate response.

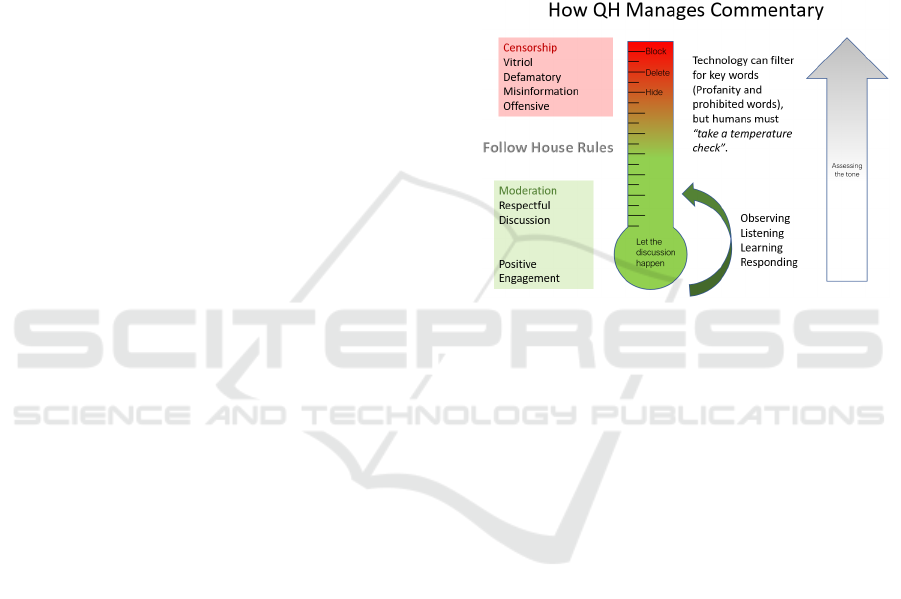

Based on the analysis, Figure 1 provides a model

demonstrating how Queensland Health manages

social media commentary. This diagram emerged

during theoretical coding (Charmaz, 2014), where

analysis is taken to the point of theory (Birks & Mills,

2022). The diagramming technique was used to focus

on the concept of a “temperature check” and look for

characteristics of and relationships with that concept,

constantly comparing what was said in all interviews

and memos and building the model iteratively. This

study found that managing social media commentary

for Queensland Health contains three important

concepts:

Observing – learning from the conversations,

what is trending, what people want to know, and what

are the gaps in informing people.

Moderating – identifying what conversations are

offensive, misinformation or controversial and could

risk reputation. This includes listening and learning.

Responding – answering questions, teaching

people how to inform themselves and removing

commentary if necessary.

Figure 1: Model demonstrating how Queensland Health

(QH) manages social media commentary.

In addressing the research question on how

Queensland Health navigates negative commentary

on social media, the ensuing discussion presents the

findings, complemented by verbatim participant

quotes in italics.

3.1 Finding 1: Negative Commentary

Promotes Discussion

A finding supported by the literature Labrecque (2022)

and echoed by the majority of participants is that all

commentary is good. Social media is a two-way

communication medium and promotes engagement.

All social media administrators reported that they

needed to let the discussion happen. By observing

social media commentary, several participants

reported it shows where the gaps are, it shows where

we are failing in information, in broadcasting

information. Participants explained that as a

government entity, Queensland Health needs to be

able to take criticism, listen, be transparent and

respond accordingly. This study found that

Queensland Health embraced community

engagement on social media and monitored respectful

discussions.

Managing Adverse Commentary on Social Media: A Case Study of an Australian Health Organisation

445

3.2 Finding 2: Negative Commentary Is

a Drawback to Using Social Media

Negative commentary is found to be the most

significant drawback of the use of social media.

Participant 7 reported that what makes it so powerful

is also what makes it dangerous. Social media is a

two-way communication channel that is continuous

and always available and has created a situation for

communications staff that extends beyond the role of

a social media administrator. For Queensland

Health’s social media audiences, there is often no

distinction that the person monitoring commentary is

not a health professional. Participant 17 reported that

members of the public send alarming messages: We

had people saying “my son’s breathing sounds funny,

what should I do” and people do that randomly

expecting an immediate response and health advice.

The most poignant examples are staff members who

receive threats of self-harm and suicide or harm to a

child. These examples demonstrate the unpredictable

nature of issues that may arise from two-way

communication.

Participants reported that social media enables

people to say what they want without repercussions,

and that can be overwhelming for organisations (Mac,

2021). While the incidents of extreme hostility are

low for Queensland Health, one participant reported

that a rabid anti-vaxxer accused the health

organisation publicly of killing children. Social media

is a platform where people can voice their opinions

publicly, and organisations need to be prepared to

have strategies to manage negative commentary

effectively.

3.3 Finding 3: Managing Negative

Commentary Requires a Response

Strategy

Participants reported that the first step in managing

negative commentary is not being quick to remove

commentary. This finding is consistent with Labrcque

(2022) and BVA News (2014). Queensland Health

has a response strategy to manage negative

commentary effectively, with participants reporting

allowing people to have that voice, have that

discussion. These findings resonate with the findings

reported by Waling (2022), Labrecque (2022), BVA

News (2014, Javornik (2020), and Johnen (2019) that

responding to and not removing negative

commentary is important. Moreover, when faced with

negative comments on social media, it is advisable to

address them with constructive feedback rather than

opting to ignore them outright (Chugh, 2012).

Queensland Health’s social media channels are

managed and monitored by the Communications

department. Policies and procedures are adhered to as

part of the response strategy. House rules are

displayed in a prominent position on each social

media channel, and policy advises that inappropriate

or offensive content, or content not in accordance

with the terms of use are to be removed. The

categorisation of content hinges on social media

administrators evaluating the tone of the commentary

(see Figure 1). In the first instance, social media

administrators will hide commentary that has

breached house rules; some administrators will

provide warnings and reminders of the house rules,

and others will just hide comments. Profanity filters

are set up within the social media channel, and if a

keyword is detected, it is automatically hidden before

human intervention, and administrators will then

assess the commentary. Some keywords may not

always be a breach and need to be checked by a

human. The next level of monitoring is to delete

commentary as per policy, but this only happens

occasionally. Further measures include blocking a

member of the community, but this is rare.

When responding to negative commentary, social

media administrators do not speak on behalf of

another staff member or on topics outside their

expertise without first seeking advice and

authorisation. It was also found that social media

administrators go beyond their role and monitor

commentary outside of hours. This was prevalent

during the COVID-19 pandemic, and participants

reported the responding workload definitely

increased. For commentary posted outside of

business hours, automated responses are set up to

acknowledge direct messages advising that a

response will be provided in a suitable timeframe and

to contact 000 if it is an emergency.

Each HHS operates under their own policy and

procedures derived from the Department of Health.

Some HHSs have pre-determined responses and will

attempt to respond within the first hour, and

acknowledgement of a post is to happen within 24

hours of receipt. This includes liking the post and

commenting to let the person know it has been

received and will message them more information. If

the question is to go to another internal stakeholder,

the customer is made aware and kept updated

throughout the process.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

446

3.4 Finding 4: Resources and Training

Are Required to Manage Negative

Commentary

Another finding in this study was that all participants

acknowledged the importance of resourcing, and

many claimed to be undeniably resource poor.

“Needing resources” emerged as a core category

linked to “managing commentary”. All participants

discussed what resources they had available, and

while a small number of participants were satisfied

with their allocation, all participants agreed we could

do more with social media and that dedicated

resources are needed.

Controversial topics such as COVID-19, anti-

vaccine, and misinformation need to be closely

monitored. However, the level of observation,

moderation, and response depends on the available

resources. The consequence of neglecting

observation, moderation, and timely response lies in

the potential for negative commentary to escalate

swiftly, leading to adverse effects on individuals and

reputational harm, as also evidenced by the literature

(Johnen & Schnittka, 2019; Labrecque et al., 2022;

Mac, 2021).

Another category that emerged linked to

resourcing was social media is a specialist role.

Participants reported that administering social media

is considered a specialist role that requires skills and

training. In most HHSs, there is not one dedicated

resource to manage social media, and

communications staff perform multiple roles,

predominantly focused on traditional media in the

form of one-way communication. It was evident in

the findings that there is a lack of training in social

media tools and response strategies in some HHSs.

Training and education play a pivotal role in

effectively leveraging the potential of social media

(Galea et al., 2023). Moreover, regular training

sessions are crucial to maintaining staff awareness of

social media policies (Daemi et al., 2020).

Studying negative commentary is an under-

researched social media phenomenon (Labrecque et

al., 2022) and more so in the field of health. The

findings in this study have a noteworthy impact for

health organisation decision-makers who influence

policy and practice, determine budgets, assign roles

and responsibilities, and allocate resources.

4 CONCLUSION

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, health communica-

tion underwent a profound transformation, witnessing

an exponential surge in audience growth for

Queensland Health, Australia. While the pandemic

was a challenging time for the health organisation, it

validated the importance of social media as a fast and

effective two-way communication tool for staff,

patients, and the public. Managing the volume of

negative commentary became an overwhelming

burden with a lack of resources. Moderating and

responding to social media commentary presents an

inherently unpredictable challenge, carrying a

heightened risk of harm or reputational damage if not

managed effectively. Observing and learning from

social media commentary is important to enable

community engagement and to continue meeting the

audience’s demands. Proactively championing the

pivotal role of social media in the digital society,

decision-makers at Queensland Health can enhance

support by allocating resources, acknowledging its

significance, and investing in the professional

development of social media administrators. Despite

reaching data saturation, generalisability is cautioned

due to the small number of participants and the

dataset from one organisation only. Future research

could expand the sample and compare findings with

other health organisations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research work has been supported by the

Australian Government’s Research Training Program

(RTP) scholarship along with CQUniversity,

Australia. We also gratefully acknowledge the

interview participants and the support provided by

Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service,

Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service,

Central West Hospital and Health Service, Children’s

Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service,

Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service, Gold

Coast Hospital and Health Service, Mackay Hospital

and Health Service, Metro North Hospital and Health

Service, Metro South Hospital and Health Service,

North West Hospital and Health Service, South West

Hospital and Health Service, Sunshine Coast Hospital

and Health Service, Torres Cape Hospital and Health

Service, Townsville Hospital and Health Service,

West Morten Hospital and Health Service, Wide Bay

Hospital and Health Service, and the Department of

Health (Queensland) in the conduct of this research.

Managing Adverse Commentary on Social Media: A Case Study of an Australian Health Organisation

447

REFERENCES

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Population Clock.

Retrieved 10 November from https://www.abs.gov.au/

AUSSTATS/abs%40.nsf/Web%2BPages/Population%

2BClock?opendocument=&ref=HPKI

Australian Government. (2021). Area of Australia - States

and Territories. Retrieved 10 November from

https://www.ga.gov.au/scientific-topics/national-locati

on-information/dimensions/area-of-australia-states-and

-territories

Batra, K., & Sharma, M. (2023). Effective Use of Social

Media in Public Health. Academic Press.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2022). Grounded theory: A practical

guide. Sage.

BVA News. (2014). Social media: Handling negative

comments. Veterinary Record, 175(17), 436-436.

https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.g6547

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd

edition.. ed.). London SAGE.

Charmaz, K. (2017). The power of Constructivist Grounded

Theory for critical inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1),34-

45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800416657105

Chugh, R. (2012). Social networking for businesses: Is it a

boon or bane?’. In Cruz-Cunha, MM, Putnik, GD,

Lopes, N, Gonçalves, P & Miranda, E (eds), Handbook

of Research on Business Social Networking:

Organizational, Managerial, and Technological

Dimensions. IGI Global: Hershey, PA., pp. 603-618.

Chen, J., & Wang, Y. (2021). Social media use for health

purposes: Systematic review. Journal of Medical

Internet Research, 23(5), e17917, 1-16.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative,

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.).

Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Daemi, A., Chugh, R., & Kanagarajoo, M. V. (2021). Social

media in project management: A systematic narrative

literature review. International Journal of Information

Systems and Project Management, 8(4), 5-21. DOI:

10.12821/ijispm080401

Demsar, V., Brace-Govan, J., Jack, G., & Sands, S. (2021).

The social phenomenon of trolling: Understanding the

discourse and social practices of online provocation.

Journal of Marketing Management, 37(11-12), 1058-

1090. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2021.1900335

Galea, G., Chugh, R., & Luck, J. (2023). Why should we

care about social media codes of conduct in healthcare

organisations? A systematic literature review. Journal

of Public Health, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-

023-01894-5

Queensland Government, (2021). Queensland Population

Counter. Retrieved 10 November from https://www.

qgso.qld.gov.au/statistics/theme/population/population

-estimates/state-territories/qld-population-counter

Hunt, I. d. V., Dunn, T., Mahoney, M., Chen, M., Nava, V.,

& Linos, E. (2022). A social media‒based public health

campaign encouraging COVID-19 vaccination across

the United States. American Journal of Public Health,

112(9), 1253-1256. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.202

2.306934

Jami Pour, M., & Jafari, S. M. (2019). Toward a maturity

model for the application of social media in health.

Online Information Review, 43(3), 404-425.

https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-02-2018-0038

Javornik, A., Filieri, R., & Gumann, R. (2020). “Don’t

forget that others are watching, too!” The effect of

conversational human voice and reply length on

observers’ perceptions of complaint handling in social

media. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 50(1),100-

119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.02.002

Johnen, M., & Schnittka, O. (2019). When pushing back is

good: the effectiveness of brand responses to social

media complaints. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 47(5), 858-878. https://doi.org/

10.1007/s11747-019-00661-x

Kelly, Y., Zilanawala, A., Booker, C., & Sacker, A. (2018).

Social media use and adolescent mental health:

Findings from the UK millennium cohort study.

EClinical Medicine, 6, 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.eclinm.2018.12.005

Labrecque, L. I., Markos, E., Yuksel, M., & Khan, T. A.

(2022). Value creation (vs value destruction) as an

unintended consequence of negative comments on

[innocuous] brand social media posts. Journal of

Interactive Marketing, 57(1), 115-140. https://doi.org/

10.1177/10949968221075820

Lupton, D., & Michael, M. (2017). “For me, the biggest

benefit is being ahead of the game”: The use of social

media in health work. Social Media + Society, 3(2), 1-

10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117702541

Mac, R. a. L., Jane. (2021). Facebook Is Worried Starbucks

Will Delete Its Page Over Hateful Comments. Retrieved

10 November from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/

article/ryanmac/facebooks-starbucks-leave-social-netw

ork-hate

Steffens, M. S., Dunn, A. G., Wiley, K. E., & Leask, J.

(2019). How organisations promoting vaccination

respond to misinformation on social media: A

qualitative investigation. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1-

12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7659-3

Waling, A., Lyons, A., Alba, B., Minichiello, V., Barrett,

C., Hughes, M., & Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. (2022).

Recruiting stigmatised populations and managing

negative commentary via social media: a case study of

recruiting older LGBTI research participants in

Australia. International Journal of Social Research

Methodology, 25(2), 157-170. https://doi.org/

10.1080/13645579.2020.1863545

Wang, Y., McKee, M., Torbica, A., & Stuckler, D. (2019).

Systematic literature review on the spread of health-

related misinformation on social media. Social Science

and Medicine,

240, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.socscimed.2019.112552

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

448