Health Scores for Generating Health-Respecting Shift Plans by Means of

an Expert System from the Perspective of Care Organisations

Damian Kutzias

a

, Sandra Frings

b

, Stefan Strunck

c

and Petra Gaugisch

d

Fraunhofer IAO, Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering IAO, Germany

fi

Keywords:

Shift Planning, Health Score, Digitalisation, Care Organisations, Care Worker, Expert System,

Health-Respecting Shift Plan.

Abstract:

The care section is an essential part of our society as well as our everyday life. It is also a section which

suffers from staff shortage. Even though the job itself is not the problem, the shortage is related to shift-related

below-average working conditions. This work focuses on health-related aspects of shift planning in order to

provide insights which can assist in improving the situation of care workers. To this end, a literature and law

analysis was followed by interviews to collect, aggregate and extend health-related rules for the shift planning

process. A list of derived rules from practice is presented in addition to a discussion of previous insights from

literature. Based on these rules, a publicly available software demonstrator was implemented for sensitisation

and to show how a health-focused shift plan generation could look like. The basis for shift plan evaluation

is a health score definition, which takes into account the number of shifts and weighted rule violations. The

demonstrator was also used on shift plan data covering several years, resulting in insights about rule violations

from practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the discussion about the shortage of skilled care

workers and the ensuring nursing care in Germany,

the stressful working conditions in the care sector are

coming to the fore. High physical and psychological

demands, high work density combined with too lit-

tle time for nursing activities, frequent overtime and

changes in shift plans as well as little room for ma-

noeuvre at work characterise the everyday life of the

care staff. This resulted in a high rate of sick leave,

high fluctuation in the care staff and reductions of

working hours. The low attractiveness of the care sec-

tor is not the result of dissatisfaction with the job it-

self, but rather the demotivating working conditions

(Rohwer et al., 2021; Rothgang et al., 2020).

The BKK Health Report of 2022 shows that em-

ployees in elderly care were absent due to illness for

an average of 33.2 days. On average, this is 15 days

more than the average of all employees in Germany

with 18.2 sick days per employee (Knieps and Pfaff,

2022).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9114-3132

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9639-6948

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6673-1904

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0195-8328

Other studies, such as the AOK-Bundesverband

(AOK-Bundesverband, 2023) or the Tech-

nikerkrankenkasse (TK Die Techniker, 2023),

confirm this trend. This vicious circle of high sick-

ness rates and increasing staff shortages resulted in

increasing workload for the remaining care staff. The

recovery phase during the non-working time is often

interrupted because care workers have to step in for

colleagues at short notice (Herrmann and Woodruff,

2019).

According to the BKK study mentioned above,

44.2 percent of geriatric care workers said that they

are currently only partially or not at all able to cope

with the higher demands of their job. This proportion

is almost twice as high as in other professions, where

it is 24.6 percent. One out of four care employees

are considering changing employers within the next

two years. More than one in five people are thinking

about giving up their profession completely (Knieps

and Pfaff, 2022). To break this vicious cycle, strategic

measures are required that aim to improve working

conditions as well as to support employees through

health-respecting shift plans.

According to the DGB Good Work Index of 2018,

69 percent of care staff work in shifts, 82 percent on

weekends, 17 percent in the night shift and 54 percent

Kutzias, D., Frings, S., Strunck, S. and Gaugisch, P.

Health Scores for Generating Health-Respecting Shift Plans by Means of an Expert System from the Perspective of Care Organisations.

DOI: 10.5220/0012557200003699

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2024), pages 121-131

ISBN: 978-989-758-700-9; ISSN: 2184-4984

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

121

in the evening shift (Schmucker, 2019). Studies show

that shift work can be stressful for both health and so-

cial life (Hirschwald et al., 2020; Jacobs et al., 2019;

Strauß et al., 2021).

Shift planning in care facilities is a tool for

scheduling staff. It has a significant impact on the

quality of patient care, the job satisfaction of care

staff and the efficiency of the facility. In addition, the

shift plans document compliance with laws, accident

prevention regulations and collective agreements, etc.

(Birkenfeld, 2000). The challenge for those persons

creating shift plans lies in taking into account the in-

terests of residents and the employees of the facility

itself. Residents demand a consistent quality of care

as well as flexibility in the provision of care.

Software applications have supported the design

of shift plans for many years. Today’s software for

shift planning is usually integrated into a software

suite used in the care domain. For care work, digital

support is particularly important for documentation as

well as planning of resources (Daum, 2022). A recent

study found out, that the majority (89 percent) of the

surveyed care organisations stated that care schedul-

ing/shift planning is predominantly performed digi-

tally (Daum, 2022). One major challenge with shift

planning is the volatility of the work - a challenge

which can be reduced with software supported solu-

tions. These systems can offer a spontaneous visu-

alisation of the consequences of a planning decision

by showing time accounts, staffing information and

information regarding rest times and other legal or er-

gonomic criteria. Shift planning can be supported to

a lesser or greater automation extent (Kubek et al.,

2020), whereat the software usually offers the option

for managing profiles for each employee/care staff

member that stores availability and personal prefer-

ences.

Planning software is usually able to show vio-

lation of relevant rules, usually predominantly law-

based rules. Due to the fact, that the systems already

stores huge sets of data regarding personnel and their

shift plans, this data could be used to extract infor-

mation regarding the “quality” of a shift plan seen as

a whole as well as on employee level. The quality

can be measured with different aspects in mind. This

work focuses on health-related quality measures, tak-

ing into account rules derived from law, science and

interviews.

The contributions of this work are as follows:

health-related rules for shift planning are presented

and discussed in three categories, extending law-

based and established rules by recommendations de-

rived from interviews. In addition, a health score is

introduced as a health-based measurement for shift

plans. Last, but not least, a demonstrator is presented

which shows an implementation of the discussed con-

cepts, emphasising the importance of visualisation of

relevant aspects. This demonstrator was also used on

data coming from practice covering several years of

shift plans providing useful insights.

The remainder of this work is structured as fol-

lows: section 2 describes the methodology of this

paper. section 3 presents the professional basis of

health-related aspects which are used for the technical

demonstrator described in section 4. Finally, section 5

comes with a conclusion and future work.

2 METHODOLOGY

The underlying research questions of the presented

work are the following two:

1. What health-related factors are relevant for the

preparation of shift plans?

2. How can the health-related factors for shift plans

be utilised (by technical means) to improve the

well-being of the care staff in care organisations?

A mixed-method approach was chosen, which in-

cluded literature research, qualitative surveys and ele-

ments from prototyping. The literature study accord-

ing to the method vom Brocke (vom Brocke et al.,

2009) started with a research on the applicable le-

gal regulations in the field of shift plans. Relevant

national and international labour laws and regula-

tions that deal with health aspects in relation to shift

plans were examined. In parallel, occupational sci-

ence sources and recommendations were evaluated in

order to create a comprehensive basis for the further

research steps.

Following this literature review, a qualitative ap-

proach was chosen to systematically answer the re-

search questions. The research method is made up of

the following steps:

1. Semi-standardised interviews were conducted to

determine the approach the persons responsible

for shift scheduling were taking and to identify the

requirements for shift planing from the staff. This

allowed for comprehensive data collection and in-

clusion of the practice perspective.

2. The interviews also included questions about cur-

rent technical support for service planning. This

helped to understand existing software solutions

and their use in the context of the care sector.

3. A detailed analysis of non-digital shift plans from

practice provided by care organisations was car-

ried out to identify further criteria for shift plan-

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

122

ning and fulfilment of the health aspects men-

tioned by the interview partners.

4. The findings were reflected with the interviewees

to ensure that the requirements and factors identi-

fied meet the needs of the practice.

5. A set of rules was formulated based on the find-

ings from the interviews, from the review of non-

digital shift plans and from the legal regulations

found in the literature review. These rule sets were

to serve as a basis for the development of the soft-

ware demonstrator that can transparently present

the health aspects in shift plans.

6. Common shift plan applications were examined

and discussions were held with manufacturers of

shift plan software in order to get to know relevant

functions and find out to what extent shift plan

design is already supported by automation and the

use of artificial intelligence (AI).

7. Criteria, requirements, rules and minimum func-

tionality for a demonstrator were fixed.

8. Based on this, a prototype demonstrator was then

specified and developed according to the pro-

totyping method by Pomberger (Pomberger and

Weinreich, 1994).

9. The result is a software demonstrator as a proof

of concept for sensitisation and motivation, which

analyses the aspects of healthy working within

shift plans and displays rule violations both in

a detailed and summarised manner as a global

“health score".

10. For a qualitative evaluation, V1.0 of the demon-

strator was presented to care experts, care organ-

isations and software manufacturers in online ap-

pointments and feedback was received.

11. Based on the feedback, V2.0 of the demonstrator

was developed and deployed as a public available

online tool for dissemination of the results.

3 HEALTH-RESPECTING

PERSPECTIVES

As already described, employees demand reliability,

a fair workload, individualisation and personal flex-

ibility. The facility itself expects compliance with

the personnel budget, economical use of working

hours, quality management and minimum legal re-

quirements, as well as minimal planning effort (Her-

rmann and Woodruff, 2019). Due to the importance

of duty scheduling in terms of keeping employees

healthy and in the care context additional of shift

work, framework conditions are recommended and in

some cases regulated by law. The most relevant as-

pects are presented in the following subsections. They

provide the basis for health-respecting shift plans and

are utilised by the technical implementation in sec-

tion 4.

3.1 Rules Derived from Laws

The legal framework for the organisation of working

time is of great importance for the protection of em-

ployees’ working conditions and for ensuring a bal-

anced relationship between work and rest. German

law is the focus of this subsection due to the fact, that

the context of our work is the German care sector and

that all of our interview partners and data providers

are from Germany. The most important law in this

respect is the Working Time Act (Arbeitszeitgesetz -

ArbZG) (Bundesministerium der Justiz, 2020). Ac-

cording to § 1 the purpose of the law is to ensure

the safety and health protection of workers. It limits

working time in Germany to eight hours per working

day. An extension to up to ten hours is permitted un-

der certain conditions. Employees may work a max-

imum of 48 hours per week. However, a 30-minute

rest break must be granted after six hours of work at

the latest, unless the total working time is less than

nine hours. If the working time exceeds nine hours,

it is 45 minutes. The rest break can be divided into

sections of at least 15 minutes each. In addition to

rest breaks, the law provides for a daily rest period of

eleven hours. This means that there must be at least

eleven hours between two work assignments. Special

provisions apply to night work. Night work within

the meaning of the Act is work that is predominantly

performed between 23.00 and 6.00 o’clock.

With regard to a limit on consecutive working

days, the German law does not provide for an explicit

maximum limit. The limit is set by other provisions,

such as Sundays off, and was limited by the Euro-

pean Court of Justice to a maximum of 12 consecu-

tive working days (Court of Justice of the European

Union, 2017).

Working time arrangements in the care sector are

particularly affected by exemptions in the law. Col-

lective agreements may go even further. For example,

it is possible to reduce the rest period to ten hours.

The laws in Germany and the other member states

of the EU are directly influenced by the European

Parliament and Council. In the Council Directive

2003/88/EC (European Union, 2003), the EU de-

fines minimum requirements for the organisation of

working time, including minimum periods of daily

rest, weekly rest and annual leave, breaks, maximum

Health Scores for Generating Health-Respecting Shift Plans by Means of an Expert System from the Perspective of Care Organisations

123

weekly working time, and certain aspects of night

work, shift work, and patterns of work. Regarding

rest time the directive states that every worker is enti-

tled to a minimum daily rest period of 11 consecutive

hours per 24-hour period. A maximum average work-

ing time of 48 hours per week, including overtime is

also specified. The directives remain unspecific re-

garding breaks and refers to agreements between the

employers and employees or by national legislation.

In the USA, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

is the federal law that regulates working hours (U.S.

Department of Labor, nd). According to the FLSA,

employees must receive at least the minimum wage

and may not be employed for more than 40 hours in

a week without receiving at least one and a half times

their regular pay rate for any hours worked over 40.

There is no federal or state law on limits to the length

of the working week, but the FLSA creates a finan-

cial disincentive to longer working hours by requiring

time and a half pay for employees working more than

40 hours in a week.

3.2 Rules Derived from Official

Recommendations from Authorities

In addition to the various legal requirements, there are

other scientifically based recommendations for work-

ing and rest times, breaks and shift work coming from

official authorities. In Germany, it is stipulated by law

that reliable scientific findings must be taken into ac-

count when dealing with working hours (§ 6 (1) Ar-

bZG) (Bundesministerium der Justiz, 2020).

With regard to working hours, a working time

of 8 hours is generally recommended (BAuA, 2016).

However, splitting shifts into two separated, shorter

shifts with a long break, which is usually not spend at

the workplace, between the two shifts, should also be

avoided (Beermann et al., 2019). Consecutive work-

ing days should also be limited, and a rest day should

be planned after 5 days (Beermann et al., 2019),

whereby individual interspersed rest days should be

avoided (BAuA, 2021) to ensure recovery (Wong

et al., 2019).

With regard to the shift work required in car-

ing, labour science recommends a forward respective

clockwise rotating shift sequence. This means that a

phase of early shifts should be followed by a phase

of late shifts, then night shifts and finally days off,

whereby the number of night shifts should be a maxi-

mum of 3 nights (Burgess, 2007; BAuA, 2016).

Other recommendations do not directly address

working time and shift planning, but concern the han-

dling of the shift plans or the organisation of avail-

able staff. Occupational science findings emphasise

the design of a better shift work. In addition to rec-

ommendations on the lengths of shifts, the rotation

from early to late and night shifts as well as the shift

sequence, the regularity and predictability of work-

ing hours are emphasised (Knauth and Hornberger,

1997; DGAUM, 2020; BGW, 2006). Especially the

plans should be predictable and plannable in order

to improve the work-life balance (Beermann et al.,

2019). Insufficient predictability of work and leisure

time leads to increased subjective health complaints

and increased dissatisfaction with own working time

arrangements (Engel et al., 2014). In this context, a

health-promoting shift plan plays an important role.

A shift plan that is based on science recommendations

and putting the needs of the employees can have a

positive impact in their satisfaction, mental and phys-

ical health, and the quality of care. A very important

aspect is the absence of changes at short notice, which

also has been confirmed to be a success criterion when

recruiting and retaining employees (Gaugisch et al.,

2017). There is no uniform opinion on the appropri-

ate lead time a shift plan should be developed and pro-

vided to the staff. Guidelines in other countries were

only found in isolated cases; the Formula Retail Em-

ployee Rights Ordinances in San Francisco, for ex-

ample, stipulate a binding two week advance notice

of work performance for certain companies (City and

County of San Francisco, 2015).

3.3 Rules Derived from Other Sources

and Interviews

In addition to the legal framework and official recom-

mendations, there is further literature on guidelines

for the design of shift plans.

A shift plan is used to regulate both the staffing

requirements and the actual deployment of staff in

care facilities. It is intended to ensure that the work-

flow is efficient, of high quality and satisfactory for

both the persons being cared for and the care worker

(Birkenfeld, 2000). Care workers have clear expec-

tations of an effective shift plan, which can be clas-

sified into the categories of reliability and planning

security, fairness, individualisation and personal flex-

ibility (Herrmann and Woodruff, 2019). In terms of

reliability and planning security, they expect, for ex-

ample, punctual closing time, regular weekends off

every 14 days and an early announcement of the shift

plan. A well-designed shift plan should also be able

to accommodate staff absences without people having

to fill in for sick colleagues at short notice or having

to work on non-working days.

In a study by the German Professional Associa-

tion for Nursing Professions (DBfK, 2019) the staff

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

124

also demand sufficient staff to adequately cover the

workload and that it should be binding at least four

weeks in advance.

In addition, the integration of buffers for short-

term staff absences is important in order to maintain

the quality of patient care. The reliability of the shift

plan is crucial and it is desirable to take individual

preferences into account.

In a collection of good practices (BGW, 2006),

measures were identified that elderly care facilities

implement with regard to labour logistics. With refer-

ence to duty scheduling, the establishment of a pool

of temporary staff is mentioned in order to ensure the

aforementioned reliability of the shift plan and to re-

duce the need to call staff in from off duty. Here too,

early provision of the plan (4 weeks) is discussed,

although in the interviews conducted as part of the

project, organisations even aim for 6 weeks in ad-

vance. In terms of shift planning, the facilities are

aiming to reduce work peaks and avoid split shifts.

In order to supplement these aspects from litera-

ture, interviews with shift planners were conducted

as part of this work. In the interviews, it was fre-

quently mentioned that employees’ wishes are con-

sidered when planning shifts. It has been confirmed

that this leads to greater acceptance of the sched-

ules and increases satisfaction. There is limited aca-

demic research specifically on the impact of consid-

ering employee wishes in shift planning on employee

health. However, there is research that suggests that

flexible work arrangements, which can include shift

scheduling, can have positive impacts on employee

well-being and health. For example, a comprehen-

sive review of shift working nurses concluded that

factors including control over shift patterns are cru-

cial factors in achieving work-life balance (Dall’Ora

and Dahlgren, 2020). Care workers want that the shift

plan takes their individual time needs into considera-

tion, for example a shift plan that can be integrated

into their rhythm of life (Herrmann and Woodruff,

2019; Kubek et al., 2019; Schmucker, 2019).

Some of these aspects were simply confirmed by

the conducted interview of us, but there were also ad-

ditional aspects and also relevant conflicts arise. Of

such conflict is that some employees’ wishes contra-

dict official recommendations or even legal require-

ments. For example, employees occurred in the inter-

views who work more than 3 days in a row at night in

order to have more time off afterwards. Others prefer

to work longer shifts (e. g. 10 hours) in order to have

more time off afterwards. This creates a conflict, at

least between the finding that taking wishes into ac-

count increases satisfaction, but according to current

findings the work is more stressful as a result.

In the interviews, various groups of people in their

organisations were identified for whom special con-

ditions and facilities apply. Employees with chil-

dren get more flexibility in the start and end times of

their shifts, which are adapted to school and childcare

times. For employees whose partners also work shifts,

their own working hours are adapted to their partner’s

so that working hours are as similar as possible and

free time can be spent together. Older employees are

offered shorter shifts or, if their working time account

allows, more consecutive days off.

In terms of other organisational aspects, full-time

employees tend to be given longer shifts to ensure

days off. For this reason, full-time employees are of-

ten scheduled first in the shift plan. Part-time employ-

ees are therefore often given slightly shorter shifts. A

special feature applies to the planning of holidays: an

attempt is made to schedule either an early shift be-

fore a desired holiday, or a late shift after the holiday,

or even a whole day off is scheduled to extend the

holiday.

The full list of health-related rules based on

employee-wishes for shift planning derived from the

conducted interviews is given in the following:

■

Early duty should be preferred on last working

days before holidays, if possible.

■

Late shifts should be preferred on first working

days after holidays, if possible.

■

Part-time workers have shorter shifts.

■

Full-time workers have longer shifts.

■

Free days are appended to holidays, if possible.

■

Shift plans of partners should be respected.

■

Times of day care centres and schools are re-

spected for care workers with (small) children.

■

Older care workers have shorter shifts.

■

Older care workers have preference consecutive

free days.

■

Shift plans should plan with net time, i. e. their

working time minus holiday times, training times,

and other predictable peculiarities.

■

Holiday planning can be finalised in December of

the last year.

■

A certain amount of wishes is respected per

month, if possible (e. g. two per month).

■

Individual needs are respected such as certain

times to bring children to their sport locations.

■

Wishes about night shifts are respected in particu-

lar.

■

Wishes can be registered until the 15th of the pre-

vious month.

Health Scores for Generating Health-Respecting Shift Plans by Means of an Expert System from the Perspective of Care Organisations

125

In practice, it usually is not possible to respect all

rules, especially when considering a multitude of in-

dividual living conditions and wishes. But trying to

respect the needs of the care workers as good as pos-

sible is both, expected and valued by the concerned

care workers.

In terms of reliability, the planers have paid par-

ticular attention to outage management. For example,

one organisation has a buffer of day workers who are

willing to cover night shifts. In addition to pools of

temporary staff, there are also resource services that

can be called upon at short notice. And finally: Stand-

ing in is usually rewarded with attractive compensa-

tion, such as an extra weekend off. The full list of

outage rules derived from our interviews is as follows:

■

Part-time workers are preferred for standing in.

■

Care workers which stand in often get a fair com-

pensation, e. g. additional free weekends.

■

There should be a reasonable amount of buffer

care workers for night shifts.

■

When organising buffers, the level of training

should be taken into account.

■

A resource service should be used for structured

outage management, i. e. care workers which

check whether they are needed or not at the be-

ginning of the day. If not, they get a compensa-

tion for staying ready, e. g. one hour of work time

noted.

3.4 Stakeholders and Their Interests

After investigating the health-related factors of shift

planning (research question 1, cf. section 2), the ques-

tion arises how these insights can be utilised (research

question 2). With already numerous law-based rules,

it is unrealistic that planners can respect the multi-

tude of health-related rules manually in a reasonable

amount of time. Therefore, the target is a software

support in form of an extension of the already used

planning tools. To this end, a software demonstrator

was implemented (cf. section 4) for sensitisation of

the main stakeholders, i. e. care workers as the most

affected group of persons, planners as those having to

create the shift plans with various requirements, em-

ployee representative committees as those, caring for

the fulfilment of many requirements to shift plans, and

last, but not least, software providers as those which

have the basis to implement the means to bring the

insights of this work to practice.

This last subsection is about the two stakeholder

groups which are most probably the main users of the

potential software support, i. e. planners during gener-

ation and employee representative committees (such

as work councils) as verifying instances. The demon-

strator was designed having these two user groups in

mind.

The works councils have a right of co-

determination with regard to duty scheduling in Ger-

many (Bundesministerium der Justiz, 2022). They

pursue various interests with regard to duty schedul-

ing, with the aim of creating a balanced and fair work-

ing environment. A central concern is to promote

the work-life balance of employees by carefully or-

ganising working hours. In doing so, the representa-

tive office emphasises compliance with working time

laws and collectively agreed provisions. Another fo-

cus is on protecting the health of employees. Duty

scheduling should be designed in such a way that suf-

ficient breaks and appropriate rest periods are taken

into account in order to avoid overwork. At the same

time, the employee representatives are committed to

involving employees in the duty scheduling process

in order to better take their needs and preferences into

account. Representation also aims to distribute the

workload fairly and ensure that employees’ qualifi-

cations and competences are appropriately taken into

account. This is not just about avoiding overwork,

but also about promoting efficient work performance.

The employee representatives are in favour of flexi-

bility in duty scheduling to make it easier to combine

work and family life. The introduction of flexible

working time models plays a key role here. Trans-

parency and open communication between employer

and employees are further key concerns in order to

recognise and resolve potential problems at an early

stage. Overall, the employee representatives strive for

balanced duty scheduling that not only fulfils opera-

tional requirements but also focuses on the needs of

employees.

Planning shifts is a major challenge for the mid-

dle care management, as it requires them to take into

account individual wishes, staffing requirements and

compliance with legal, collective bargaining and er-

gonomic standards. In the "Game of Roster" project

(GamOR), a digital collaborative shift planning sys-

tem was developed for care workers that motivates

employees to participate in the shift planning process

(Kubek et al., 2020). In the requirements analysis,

shift planners complained above all about the amount

of time it takes to create shift plans. Those responsi-

ble for duty scheduling are regularly confronted with

several conflicting objectives when it comes to tak-

ing into account legal and economic requirements, er-

gonomic findings and individual wishes. In addition,

economic requirements to plan shifts with only a min-

imum number of staff and the high sickness rate of

employees lead to time-consuming shift plan changes

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

126

at short notice (Kubek et al., 2019). Therefore, it is

helpful for the shift planner to be provided with all

information in a clear and transparent manner. This

includes information on where legal requirements or

requirements found in scientific sources on healthy

working. The plan could then be adapted and the up-

dated result could be showed immediately.

Another added value for the planners is, that with

a tool support for rules and wishes, they have concrete

data about the care workers which can not only be

used to ensure fairness, but also to communicate on a

solid basis.

With these use cases and target groups in mind,

a technical software demonstrator was developed,

which is the subject of the following section.

4 DEMONSTRATOR FOR

HEALTH-RESPECTING SHIFT

PLANNING

The sheer number of different rules makes it ex-

tremely difficult to respect them all as a human plan-

ner during shift plan generation. Even though shift

plan generation by means of a planning software has

become standard (cf. section 1) over the last years, the

majority of such tools provide assistance, but hardly

any automation to their users (Petrovic, 2019). Given

the assisted process of shift plan generation, trans-

parent visualisation of rules and their compliance be-

comes an important feature of these assisting systems,

since otherwise their users have to care about rule

compliance, manually check them during the genera-

tion process, or check in the end and adapt an already

finished shift plan again when compliance problems

are found.

Unfortunately, existing tools only provide assis-

tance regarding a small amount of the rules described

in section 3. Usually, the rules given by law are

mainly covered, the others not. This may be because

software in this area rarely profits from developed

models and methods (Petrovic, 2019).

With the goal of sensitisation by showing what can

be done and how it can be implemented, a techni-

cal software demonstrator was developed. This sec-

tion presents this demonstrator to show how health-

related rules beyond laws could be implemented and

visualised during the process of shift plan generation.

The demonstrator is freely available in the internet

(Kutzias et al., 2022).

4.1 Rule Violations and Health Score

When going beyond the law-based rules, it becomes

unrealistic to always fulfil all different rules all the

time for all care workers. This has been confirmed by

the conducted interviews, the literature (cf. section 1)

and the analysed data from practice. In such a situ-

ation, a measure of quality for evaluation and com-

parison of different shift plan time intervals can help

the responsible persons to keep track of the quality of

their shift plans during generation.

Different rules can differ heavily in relevance.

Therefore, a simple count of rule violations, which

cannot grasp such differences, is not the best measure.

In addition, some rules can conflict and also their rel-

evance can be based on individual preferences. Par-

ents, for example, might optimise their time together

with their children at the cost of ignoring other health-

related aspects. Time with the children can also be a

health-relevant factor, which can also heavily affect

the well-being of a human (Milkie et al., 2010).

Whereas a total count of (weighted) rule viola-

tions is interesting information, the relation of vio-

lations and the amount of work might be even more

helpful. Even on a per-person level, this might be very

important, e. g. for part-time care workers. Based on

these considerations, the following requirements for

such a measure were derived:

1. Violations should be relative to the amount of

work performed.

2. Rules should have a configurable relevance.

3. Individual preferences should be respected.

4. The measure should be intuitively understandable

and comparable.

A concrete measure - namely "health score" - is

proposed to be able to compare shift plans regarding

their health-related quality based on the four require-

ments mentioned above. The basis is the number of

shifts defining the maximum number of quality points

which is achievable (Requirement 1). For all occur-

ring violations, the penalty points are summed up re-

specting possible differences depending on the care

worker for which the violations occur (Requirement

2 and Requirement 3). Based on these two values, a

ratio is used to calculate a value between 0 and 100

to indicate the quality of the shift plans (Requirement

4). In the following, a more detailed and formal defi-

nition of this value, the health score, is given.

Definition 1 (Health Score). Let S be the set of shifts

in the corresponding shift plan, C the set of avail-

able care workers and V the set of violations with

c

v

∈ C the corresponding care worker for each vio-

lation v ∈ V and p : V ×C → N

0

the function assign-

Health Scores for Generating Health-Respecting Shift Plans by Means of an Expert System from the Perspective of Care Organisations

127

ing the penalty to a violation in combination with a

concrete care worker. w is a constant weight for the

shifts, which can be fixed for application. Then the

health score HS is defined as:

HS = max

0, 100 ·

|S| · w −

∑

v∈V

p(v, c

v

)

|S| · w

Since the penalty points are flexible, it is no re-

striction to fix a constant weight of points per shift.

This constant weight value should simply be chosen

high enough for the desired possible relation of the

different rules (as long as staying with integers) and

granularity of the violation point definition. Since

the sum of penalties can exceed the number of maxi-

mum points, a minimum of 0 is set by using the max-

imum function, so that the desired interval of [0, 100]

is achieved.

4.2 Technical Implementation

To show how health-respecting shift plan generation

can look like, a technical demonstrator was devel-

oped. It consists of the following main functionali-

ties: a calendar for shift plan generation, care worker

management with master data, a configurable rule set

for health score calculation, a measurement engine

for shift plan evaluation and health score calculation,

and a visualisation of rule violations and the health

score. This subsection gives a concise description of

the demonstrator and its implementation of the previ-

ously mentioned aspects.

Web technologies were used to provide an easy

Internet access: the server back-end was implemented

using Node.js with express as the webserver. On the

front-end side, jQuery and jQuery UI were the main

frameworks for implementation.

Since it is meant to be a demonstrator, not a soft-

ware product for sale, some restrictions were made:

■

Only a subset of identified rules were imple-

mented.

■

Only single source violations were visualised di-

rectly in the calendar.

■

Due to data protection reasons, fictional data was

used for public show cases.

■

For simplicity, rule configuration is made on shift

plan instead of care worker level.

The health score was implemented with w = 15

resulting in a maximum number of 15 times the num-

ber of shifts. Due to the rule configuration handling,

violation penalties are calculated per rule type.

For the available care workers, master data is re-

spected such as date of birth, hours per week, level

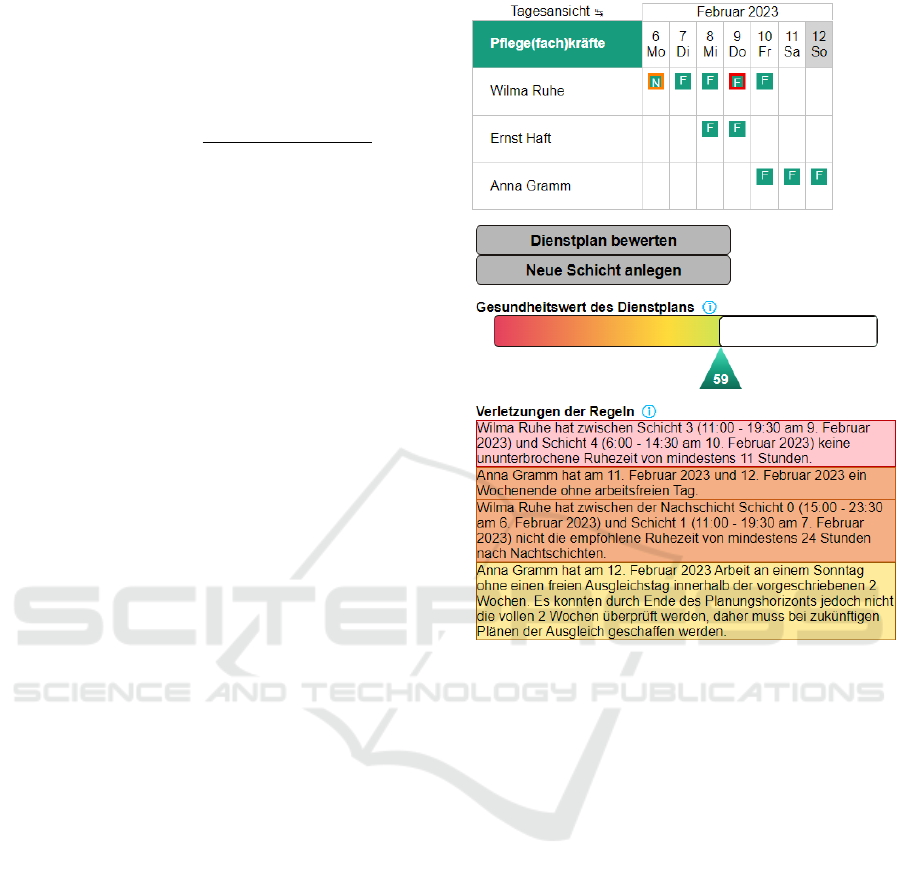

Figure 1: A small sample shift plan in the demonstrator

for one week with several rule violations. Red is used for

law rule violations, orange is used for official recommenda-

tion rule violations and yellow for unofficial rule violations.

This sample sums up to a health score of 59, indicated by

both, by the number under the bar and the filling of the bar.

of training, several pregnancy-related data, and law-

based special permissions for youth work. For per-

formance reasons, rule checking is not done automat-

ically on each and every change in the shift plan, but

on button click: the shift plan is sent to the server

which calculates rule violations and sends them back.

These rule violations are then visualised in the calen-

dar, in a percentage-based filled bar with the health

score and a list of all violations given beneath the bar.

A sample of the demonstrator with an already checked

shift plan with three care workers and a time interval

of one week can be seen in Figure 1.

In addition to the online functionalities, a module

was implemented for automatic processing of larger

data sets for analysing real data. This module is not

part of the online demonstrator to avoid contract data

processing issues. It was used for analysing data cov-

ering several years coming from practice using the

same rule set and code as the online demonstrator

uses.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

128

4.3 Rules and Violation Visualisation

When rules are implemented in software, questions

about the user interface and the presentation arise.

Immediate visual feedback is only possible by live

evaluation and presentation. In addition, it is advis-

able to visualise rule violations as close as possible to

the shifts and care workers related to the violations,

to enable planners to efficiently locate violations and

react to it.

To be able to visualise rule violations inside a

planning tool with a calendar, different rules were

grouped by their relevant time intervals in the follow-

ing way:

■

Single Source Violations: Violations caused

within a single work shift are the most simple

class and can be visualised by highlighting the re-

lated shift or day. An example for this can be seen

in Figure 2.

■

Multi Source Violations: Violations caused

across several shifts or days can, for example, be

visualised by overarching visual elements for con-

secutive elements such as a coloured overlay bar

for a few days or by simply highlighting all single

elements, presenting their unity by changing the

highlighting of all of them on hovering over one

of them.

■

Long Interval Violations: Violations which are

related to days and shifts with large time differ-

ences are hard to visualise in a calendar. One pos-

sibility, for example, would be by highlighting the

care worker or some kind of list next to the plan-

ning area.

A concrete delimitation between multi source vi-

olations and long interval violations was intentionally

not defined, since the meaningfulness of such a def-

inition might depend on the concrete use case and

software. It could be meaningful to define it simply

by consecutiveness, a number of days between the

earliest and the latest (e. g. seven), or count every-

thing exceeding the boundaries of the current month

as a long interval violation. The last definition would

be meaningful, since many enterprises generate their

shift plans in a monthly fashion according to the gath-

ered shift plan data and the conducted interviews.

This results in calendar views showing single months

in many planning tools.

4.4 Analysis of Historical Shift Plan

Data

According to the methodology described in section 2,

the demonstrator was used for sensitisation and col-

Figure 2: An example for the visualisation of a single source

violation. The leftmost cell represents a single day with a

shift without any violations, the second left represents a day

with a shift with a single source violation and on the right

the same cell is shown with a hovering effect. A block in

a cell representing a day with an "F" denotes an early shift

that day.

lecting feedback from providers of shift planning

software and users from care organisations. Espe-

cially, the the care organisations which assisted as

providers of shift planning data from practice re-

ceived a demonstration in conjunction within the last

interview-session.

A data set covering several years was evaluated

for investigating trends over several years using the

example of one care organisation. Four years of shift

plan data (September 2018 to October 2022) was re-

ceived. Data from planned as well as actual shifts

from 53 care workers was analysed using the demon-

strator. Surprisingly, the differences between planned

and actual shifts showed a comparably small amount

of differences in rule violations. However, there was

a relevant amount of rule violations overall. On the

positive side, it was shown that the health score was

trending upwards, i. e. the overall amount of rule vio-

lations decreased over time, starting with round about

40 going up and staying around 90 over the last two

years. On the other hand, several health-related rules

had an upwards trend in the amount of related viola-

tions as described in the following:

■

Required free compensation days for work on

Sundays within the following two weeks had an

upwards trend in violations ending with roughly

0.36 violations per care worker per month.

■

The recommendation that at least one day should

be free of work on weekends was often violated

with an upwards trend ending at 2.32 violations

per care worker per month.

■

The recommendation that not more than five days

per week should be used for work had an upwards

trend in violations ending with 1.53 violations per

care worker per month.

When analysing the average rule violations per

care worker per month, it was observed that individual

care workers had up to a factor of five times as many

violations as the average of all care workers. Even

though the cause is not confirmed, it may be due to

the "yes-person" character of those care workers.

These insights affirmed what has been stated in

Health Scores for Generating Health-Respecting Shift Plans by Means of an Expert System from the Perspective of Care Organisations

129

the literature several times: the working conditions

in the care sector have much room for improvement.

The care organisations were surprised by several of

the numbers and trends in the feedback discussions,

especially about the individual persons with drastic

violation peaks.

The analysis of data from practice gave insights

about possible reasons for problems of the health

sector such as the sickness rate and dissatisfaction

of many care workers. These insights in combina-

tion with the used techniques (health-related rules,

health score, visualisation during shift plan genera-

tion) could be utilised by commercial software tools

to balance the health related aspects in practice to

achieve more fair and healthy work conditions.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

Shift planning was analysed regarding health-related

aspects. In addition to existing law-based rules and

official recommendations, further recommendations

were derived from interviews with care workers. The

majority of different rules is far from being respected

in practice and often there are large balancing issues

between different care workers, as both, the inter-

views and the analysis of several years of shift plan

data show. To be able to measure shift plans with re-

spect to these health-related rules, a health score was

formally defined.

In order to prepare the next step by sensitising and

showing how it can be done, a software demonstra-

tor was developed as a publicly available web-tool,

which implements many of the discussed rules and

shows how they could be utilised by or being inte-

grated into software planning tools. The demonstrator

received a lot good feedback during the feedback ses-

sions with the interview partners, showing the need

of the planners in practice. Software providers were

more reserved, but also interested.

Besides bringing the health-related rules to soft-

ware planning tools and making the shift planning

process more fair and transparent, further interesting

research and development steps were considered.

Given the challenge of shift planning with a mul-

titude of different (health-related) rules to consider, a

next logical step would be to (partially) automate the

process of shift plan generation. Since the general

problem of generating optimal shift plans with given

restrictions is too hard to reliably compute optimal so-

lutions, at least with the current state-of-the-art (it is

an NP-hard problem (Aickelin and Dowsland, 2000)),

approximations are the main way to solve the prob-

lem. AI can be utilised to calculate such approxima-

tions. For this step to be done, a large amount of his-

torical data is likely to be required. Given the amount

of rule violations in practice, current data should not

be used in an unlabelled way if the health-related as-

pect is to be respected, i. e., for given shift plans, a

quality measure either as a number or clear category

is needed. Such data is hard to acquire, since usu-

ally, hardly anyone cares about rating past shift plans.

The proposed health score presented in this work is

a quality measure which could be used for providing

such a rating by automatically processing past shift

plans, but it depends on making the decisions about

the configurable weights in a generic manner. Further

research on this end could help to automate the shift

plan generation process.

Additionally, more simple local automation steps

could be implemented such as searching for possible

local swaps and offering them to the planners, but this

limited approach cannot guarantee to provide valid lo-

cal solutions, if none exists. Nevertheless, using such

an approach with comparison of local swaps (for ex-

ample, using the health score), a suggestion system

can be implemented to assist in doing fast adaptions.

Such a system would especially be meaningful for re-

quired short-term-adaptions, possibly caused by sick-

nesses of care workers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The acquisition of the used data as well as the im-

plementation of the demonstrator were performed

within the German project »Regionales Zukunftszen-

trum „pulsnetz.de - gesund arbeiten”« funded by the

Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

REFERENCES

Aickelin, U. and Dowsland, K. A. (2000). Exploiting

problem structure in a genetic algorithm approach to

a nurse rostering problem. Journal of Scheduling,

3(3):139–153.

AOK-Bundesverband (26.04.2023). Krankenstand in der

Pflege: Anstieg um mehr als 44 Prozent in elf Jahren.

BAuA (2016). Handbuch zur Handbuch Gefährdungs-

beurteilung „Arbeitszeit“. Bundesanstalt für Ar-

beitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin (BAuA).

BAuA (2021). Handbuch Gefährdungsbeurteilung - Teil 2:

10 Arbeitszeitgestaltung. Bundesanstalt für Arbeitss-

chutz und Arbeitsmedizin (BAuA).

Beermann, B., Backhaus, N., Tisch, A., and Brenscheidt,

F. (2019). Arbeitswissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse

zu Arbeitszeit und gesundheitlichen Auswirkungen.

baua: Fokus.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

130

BGW (2006). al.i.d.a - Arbeitslogistik in der stationären

Altenpflege - Projektabschlussbericht.

Birkenfeld, R. (2000). ABC der Dienstplangestaltung: Ar-

beitszeitflexibilität und neue Arbeitszeitmodelle im

Gesundheitswesen.

Bundesministerium der Justiz (2022). Betriebsverfassungs-

gesetz.

Bundesministerium der Justiz (22.12.2020). Arbeitszeitge-

setz: ArbZG.

Burgess, P. A. (2007). Optimal shift duration and sequence:

recommended approach for short-term emergency re-

sponse activations for public health and emergency

management. American Journal of Public Health, 97

Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S88–92.

City and County of San Francisco (2015). Formula Retail

Employee Rights Ordinances.

Court of Justice of the European Union (2017). The weekly

rest period for workers does not necessarily have to

be granted the day following six consecutive working

days: Press Release No 115/17 to Case C-306/16.

Dall’Ora, C. and Dahlgren, A. (2020). Shift work in nurs-

ing: closing the knowledge gaps and advancing inno-

vation in practice. International journal of nursing

studies, 112:103743.

Daum, M. (2022). Die Digitalisierung der Pflege in

Deutschland: Status quo, digitale Transformation und

Auswirkungen auf Arbeit, Beschäftigte und Quali-

fizierung. DAA-Stiftung Bildung und Beruf, Ham-

burg.

DBfK (2019). Ergebnisse einer Online-Umfrage zum ‚Di-

enstplan‘.

DGAUM (2020). Leitlinie "Gesundheitliche Aspekte und

Gestaltung von Nacht- und Schichtarbeit.

Engel, C., Hornberger, S., and Kauffeld, S. (2014). Organ-

isationale Rahmenbedingungen und Beanspruchun-

gen im Kontext einer Schichtmodellumstellung nach

arbeitswissenschaftlichen Empfehlungen — Spielen

Anforderungen, Ressourcen und Personenmerkmale

eine Rolle? Zeitschrift für Arbeitswissenschaft,

68(2):78–88.

European Union (2003). Directive 2003/88/EC of The Eu-

ropean Parliament and of The Council. Official Jour-

nal of the European Union.

Gaugisch, P., Risch, B., Strunck, S., and Willmann, R.

(2017). Pflegepersonalsurvey - Arbeitgeberattraktiv-

ität und Führungsmotivation in der Altenhilfe.

Herrmann, L. and Woodruff, C. (2019). Dienstplanung im

Stationären Pflegedienst: Methoden, Tools und Fall-

beispiele. Gabler, Wiesbaden.

Hirschwald, B., Nold, A., Bochmann, F., Heitmann, T.,

and Sun, Y. (2020). Chronotyp, Arbeitszeit und Ar-

beitssicherheit. Zentralblatt für Arbeitsmedizin, Ar-

beitsschutz und Ergonomie, 70(5):207–214.

Jacobs, K., Kuhlmey, A., Greß, S., Klauber, J., and

Schwinger, A., editors (2019). Mehr Personal in

der Langzeitpflege - aber woher?, volume 2019 of

Springer eBook Collection. Springer, Berlin, Heidel-

berg.

Knauth, P. and Hornberger, S. (1997). Schichtarbeit

und Nachtarbeit: Probleme, Formen, Empfehlungen.

Bayer. Staatsministerium f. Arbeit u. Sozialordnung,

Familie, Frauen u. Gesundheit, München, 4 edition.

Knieps, F. and Pfaff, H., editors (2022). Pflegefall Pflege?,

volume 2022 of BKK Gesundheitsreport. MWV

Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft,

Berlin.

Kubek, V., Blaudszun-Lahm, A., Velten, S., Schroeder,

R., Schlicker, N., Uhde, A., and Dörler, U. (2019).

Stärkung von Selbstorganisation und Autonomie der

Beschäftigten in der Pflege durch eine digitalisierte

kollaborative Dienstplanung. In Bosse, C. K. and

Zink, K. J., editors, Arbeit 4.0 im Mittelstand, pages

337–357. Springer Gabler, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Kubek, V., Velten, S., Eierdanz, F., and Blaudszun-Lahm,

A. (2020). Digitalisierung in der Pflege: Zur Unter-

stützung einer besseren Arbeitsorganisation. Springer

Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Kutzias, D., Frings, S., Strunck, S., and Gaugisch, P. (2022).

pulsnetz Demonstrator: https://pulsnetz-demo.

iao.fraunhofer.de.

Milkie, M. A., Kendig, S. M., Nomaguchi, K. M., and

Denny, K. E. (2010). Time With Children, Children’s

Well–Being, and Work–Family Balance Among Em-

ployed Parents. Journal of Marriage and Family,

72(5):1329–1343.

Petrovic, S. (2019). “You have to get wet to learn how to

swim” applied to bridging the gap between research

into personnel scheduling and its implementation in

practice. Annals of Operations Research, 275(1):161–

179.

Pomberger, G. and Weinreich, R. (1994). The role of proto-

typing in software development.

Rohwer, E., Mojtahedzadeh, N., Harth, V., and Mache, S.

(2021). Stressoren, Stresserleben und Stressfolgen

von Pflegekräften im ambulanten und stationären Set-

ting in Deutschland. Zentralblatt für Arbeitsmedizin,

Arbeitsschutz und Ergonomie, 71(1):38–43.

Rothgang, H., Müller, R., and Preuß, B. (2020). BARMER

Pflegereport 2020: Belastungen der Pflegekräfte und

ihre Folgen, volume Band 26 of Schriftenreihe zur

Gesundheitsanalyse. BARMER, Berlin.

Schmucker, R. (2019). Arbeitsbedingungen in Pflege-

berufen: Ergebnisse einer Sonderauswertung der

Beschäftigtenbefragung zum DGB-Index Gute Arbeit.

In Jacobs, K., Kuhlmey, A., Greß, S., Klauber, J.,

and Schwinger, A., editors, Mehr Personal in der

Langzeitpflege - aber woher?, Springer eBook Collec-

tion, pages 50–59. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Strauß, R., Tisch, A., Vieten, L., and Wehrmann, J. (2021).

Hohe Anforderungen, wenig Ressourcen: Arbeit-

szeiten in der Alten- und Krankenpflege.

TK Die Techniker (11.05.2023). Zum Internationalen Tag

der Pflegenden: Krankenstand bei Pflegekräften auf

Rekordhoch.

U.S. Department of Labor (n.d.). Wages and the Fair Labor

Standards Act.

vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Niehaves, B., Riemer, K., Plat-

tfaut, R., and Cleven, A. (2009). Reconstructing the

giant: On the importance of rigour in documenting the

literature search process. 17th European Conference

on Information Systems (ECIS).

Wong, I. S., Popkin, S., and Folkard, S. (2019). Work-

ing Time Society consensus statements: A multi-level

approach to managing occupational sleep-related fa-

tigue. Industrial health, 57(2):228–244.

Health Scores for Generating Health-Respecting Shift Plans by Means of an Expert System from the Perspective of Care Organisations

131