Humour in Educational Robots: Investigating the Effects of Humour

in a Robot-Led Scrumban Simulation in Business Education

Ilona Buchem

a

, Niklas Bäcker

b

, Ayline Trutty

c

, Emily Thomas

d

and Kerim Dincel

e

Communications Lab, Berlin University of Applied Sciences, Luxemburger Str. 10, Berlin, Germany

Keywords: Educational Robots, Social Robots, Humour, Teaching Strategies, Daily Scrum, Business Education.

Abstract: Educational robots have been used as technologies to support social interactions with learners and enhance

both cognitive and affective learning outcomes. While studies have shown positive impact of humour both in

education and human-robot interaction, little is known about the impact of humour enacted by educational

robots. This paper presents a between-subjects, randomized study, that explored the effects of humour on the

perception of the robot competence and facilitation, as well as learning experience, and outcomes of 30

undergraduate students during a Scrumban simulation with the robot NAO in business education settings. The

humorous version was programmed using positive humour with selected jokes and witty remarks generated

by ChatGPT. The results of statistical analysis showed a range of differences in the perception of the robotic

facilitator, the learning experience, and the learning outcomes in the humorous compared to the neutral

condition. The results of the study provide preliminary evidence on the effects of humour in educational

robots. While this study demonstrates the potential of “humoroids" and the participants favoured robot-

enacted humour as a means to create a more enjoyable and relaxed learning environment, the generalisability

of the results is limited by the absence of statistically significant findings.

1 INTRODUCTION

Educational robotics and robots have been used in

computer-supported education since the early 1980s.

Traditionally, educational robotics (ER), including

programmable toys such as Bee-bots and platforms

such as LEGO® Mindstorms®, have been applied in

STEM education to foster mathematical,

computational, and engineering skills, problem-

solving and teamwork (Gubenko et al., 2021). A

systematic review of studies on ER is provided by

Anwar et al. (2019). Recently, there has been a shift

in the application of ER, moving beyond their

traditional use in STEM to actively support learning

through meaningful social interactions with learners

(Belpaeme, et al. 2018). Social robots like NAO can

perceive, listen, and communicate in a manner

reminiscent of human interactions. Social robots'

educational potential lies in their physical presence,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9189-7217

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6920-7139

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-7242-3380

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-0789-0540

e

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6216-5060

friendly appearance, and multimodal interface

design, enabling human-like communication via

speech, gestures, eye gaze, and touch (Belpaeme, et

al. 2018; OECD, 2021; Buchem & Baecker, 2022).

Social robots have been applied to support educators

as instructors, tutors, or assistants who are able to

engage learners in more human-like ways compared to

other educational technologies (OECD, 2021).

Numerous studies have indicated that social robots can

effectively enhance the overall educational experience

as well as cognitive and affective learning outcomes,

often comparable to human instructors (Belpaeme, et

al. 2018). Despite a surge in research in ER in recent

years, studies examining the impact of humour in

social robots on the learning experience and the

achievement of learning outcomes, remain scarce.

Our study investigates how robot-enacted humour

influences students' perceptions of robotic

facilitation, learning experience, and outcomes. Our

314

Buchem, I., Bäcker, N., Trutty, A., Thomas, E. and Dincel, K.

Humour in Educational Robots: Investigating the Effects of Humour in a Robot-Led Scrumban Simulation in Business Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0012557400003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 314-321

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

research extends our prior studies, where we

employed NAO as a facilitator to support students in

acquiring skills related to agile practices through

playful, hands-on learning experiences (Buchem &

Baecker, 2022; Buchem, Christiansen & Glißmann-

Hochstein, 2023). The study presented in this paper

applied NAO as a facilitator of a Scrumban session.

The research question was: How will the use of

humour by an educational robot affect students’

perceptions of the robotic facilitator and robot-led

facilitation, as well as students’ learning experience,

and learning outcomes?

Our primary hypothesis was that the use of robot-

enacted humour would result in higher ratings of the

robotic facilitator’s competence, the quality of the

robotic facilitation and the learning experience

compared to the neutral condition. Our secondary

hypothesis was that the use of robot-enacted humour

would result in lower ratings of learning outcomes

compared to the neutral condition, which may be

perceived as more serious and/or less distracting, and

thus more appropriate for educational settings.

This paper is structured as follows. After this

introduction, we delve into related work focusing on

humour in education and human-robot interaction

(HRI). Then we detail our study design and scales

employed in the study. After that we present study

results and end with a discussion and conclusions.

2 RELATED WORK

Humour is a human communication tool, which is

often used to evoke positive reactions (Lynch, 2002).

Conversational humour is a complex multifaceted

construct, which includes jokes (statements with a

punch-line), puns (wordplay with multiple

meanings), sarcasm (sharp statements with a

humorous undertone), anecdotes (humorous stories),

and witticisms (clever, amusing remarks) (Dynel,

2009). Humour is related to non-verbal behaviours

such as laughter (Bechade et al., 2016), and includes

cognitive processes, while laughter is triggered by

humorous stimuli (Mirnig et al., 2016). Research in

cognitive psychology shows that comprehension and

appreciation of humour require cognitive effort (Suls,

1983), and are linked to higher cognitive and

emotional intelligence (Johanson et al., 2020).

Studies have shown that different types of humour

may influence outcomes. Samson & Gross (2012)

showed that positive (but not negative) humour is an

effective form of emotion regulation. Mirnig et al.

(2016) compared the use of self-irony and

Schadenfreude (as an experience of satisfaction

derived from the misfortune of others), as two types

of robot-enacted humour and found out that

participants significantly preferred robot-enacted

self-irony over Schadenfreude. Gorham &

Christophel (1990) showed that the amount and type

of humour influence learning, such that personal and

general anecdotes are related to positive attitudes

towards a teacher, while tendentious (sarcastic)

humour tends to diminish affect. Stoll, Jung & Fussell

(2018) compared a human and a robot conflict

mediators and showed that while affiliative humour

(which implies equality), and aggressive humour

(which implies superiority), was perceived as more

appropriate for a human, self-defeating or self-

deprecating humour (which implies inferiority) was

rated as more appropriate for a robot, implying a

favourable human-robot hierarchy. Our study applied

positive type of humour (see Section 3.1).

2.1 Humour in Education

Humour is an important tool for conveying

information and an excellent entry point in the

classroom (Mora, Weaver & Lindo, 2015). Applying

humour in education has both cognitive-affective and

pedagogical effects (Musiichuk, Gnevek &

Musiichuk, 2018). Humour can be used as a tool to

encourage attention, creativity, and critical thinking,

create a relaxed learning environment, and support

social interactions among students (Mora, Weaver &

Lindo, 2015). Teacher humour is associated with

being amusing and making students laugh, e.g. by

using funny words, actions, or reactions, while

interacting with students, managing a classroom, and

setting a tone for learning activities (Lovorn &

Holaway, 2015). Although humour tends to improve

students' perceptions of teacher's competence,

intelligence, and friendliness, empirical evidence of

its impact on learning remains inconclusive (Gorham

& Christophel, 1990). Lovorn & Holaway (2015)

showed that while teachers associate humour with

educational benefits, they do not deliberately include

humour, but rather rely on impromptu strategies in

the classroom. The appreciation of humour combined

with reluctance and discomfort in using it (Morrison,

2008), was called a “humour paradox in education”

(Lovorn & Holaway, 2015).

2.2 Humour in HRI

Conversational agents equipped with humour have

been called “humouroids” (Dybala et al., 2009).

Research exploring the impact of humour in robots as

conversational agents is still scarce (Johanson et al.,

Humour in Educational Robots: Investigating the Effects of Humour in a Robot-Led Scrumban Simulation in Business Education

315

2020). A social robot can use humour to engage or

interact with students by using jokes and witty

comments to evoke positive reactions and make itself

more likeable and approachable (Lovorn & Holaway,

2015). Niculescu et al. (2013) explored how humour

influenced the quality of interaction with a social

robot receptionist and found that it improved the

perception of task enjoyment and robot personality.

Stoll, Jung & Fussell (2018) showed that self-

defeating humour in robots in simulated conflict

situations created a favourable human-robot

hierarchy with the robot in an inferior position.

Research shows that making humanoid robots act

emotionally, helps to make humans feel more

comfortable. For example, when a robot expresses

human-like emotions, such as surprise, agreement,

sympathy, and approval, humans tend to nod and

smile (Li et al., 2017). Omokawa et al. (2019) found

that phatic dialogues of social robots, intended to

support social relationships, elicit laughter and smiles

from participants, compared to query dialogues

aimed at conveying specific information. The study

by Johanson et al. (2020) on the use of humour by a

healthcare robot found that the use of humour resulted

in significantly higher perceptions of the robot’s

likeability, safety, empathy, and sociability, and that

significantly more participants laughed during an

interaction with a “humouroid”. Research also

indicates that humour may be more effective for non-

task-oriented agents, e.g. with focus on entertainment

(Dybala et al., 2009).

Our study applied a social robot as a task-oriented

agent, who facilitated a Scrumban session, thus

leaving some uncertainty about how the use of

humour may impact the learning experience.

3 STUDY DESIGN

The study design draws on our past studies with NAO

applied as a facilitator of agile practices such as Daily

Scrum (Buchem & Baecker, 2022) and Planning

Poker (Buchem, Christiansen, & Glißmann-

Hochstein, 2023). This study was designed as a

Scrumban session, and was part of the agile project

management course in the undergraduate program in

Digital Business (BSc.). In this course, students learn

agile practices, such as Scrum, Kanban, and

Scrumban. The Scrumban session aimed to provide

students with a hands-on experience of a daily stand-

up meeting combined with the use of a Kanban board

to visualise a workflow (Petricioli & Fertalj, 2022).

Scrumban is a versatile and hybrid agile

methodology, which allows for larger team sizes

compared to Scrum (Alqudah & Razali, 2018). The

Scrumban session included two roles played by

students: (a) team member, and (b) agile coach.

Students in the role of team members (10 students per

condition) directly engaged in the daily standup

meeting with a Kanban board. Students in the role of

agile coaches (5 students per condition) observed the

session and provided feedback to team members after

the session. The team size of 10 with 5 agile coaches

allowed us to create a hands-on experience for the

cohort of 30 students (15 students per condition).

The study design included the preparation of

didactic materials for a semi-scripted role-pay in the

Scrumban session: (a) a script for team members with

three daily scrum questions and answers, and (b) an

observation template for agile coaches with points

related to workflow improvements. These materials

aimed to alleviate cognitive workload (Gittens, 2021)

associated with a novel situation of a Scrumban

simulation with a robot and in English (foreign

language), allowing students to focus on methods and

procedures of Scrumban.

3.1 Design of Robot-Enacted Humour

Drawing from research on humour in education and

HRI, we designed a humorous version of the

Scrumban session with NAO, incorporating two

types of conversational humour: short jokes and witty

remarks, following Dynel's (2009) classification. The

study was conducted with business students in

Germany. Considering that English was not their

native language, we opted to exclude three other types

of humour from Dynel's (2009) classification: puns,

sarcasm, and anecdotes, as too challenging for non-

native speakers.

We used ChatGPT 3.5 to generate short jokes and

witty remarks for the humorous version. From the

pool of 20 ChatGPT-generated responses we selected

six jokes (e.g. “Ok team, let me ask you a question:

Why do Scrum teams love the beach? Because they

can always count on a good stand-up!”) and six witty

remarks (e.g. "So, team, let's channel our inner Usain

Bolt and sprint through these updates. Keep your

energy and remember we are running a quick

sprint!”). Additionally, we used funny motivational

prompts (e.g. “You go rockstar!”), which place

students in a superior position, possibly creating a

favourable hierarchy (Stoll, Jung & Fussell, 2018).

3.2 Application Design

The Scrumban application for NAO Power V6

Educator Pack was written in Python and designed

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

316

using Choregraphe software Version 2.8.6. The

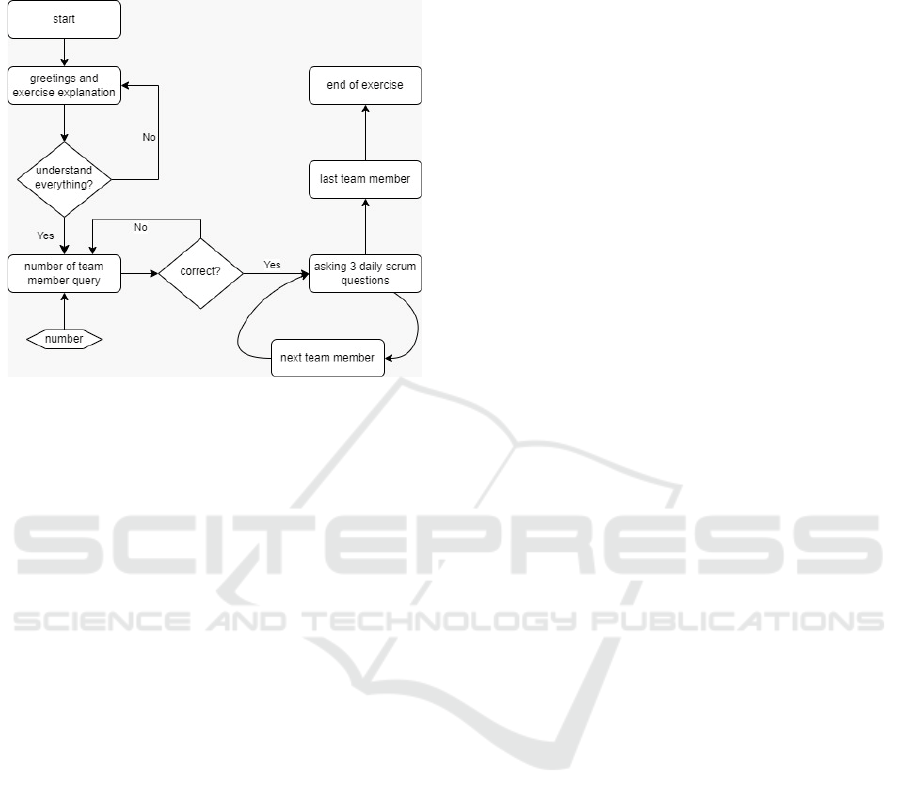

general flow used both in the neutral and the

humorous versions is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the Scrumban application.

The interaction with the robot included verbal

communication through speech and non-verbal

interaction through tactile sensors positioned at the

tip of each foot and on the head of the robot. We used

the "Switch Case" box in Choregraphe to record the

number of team members. This box is a programming

module used to control the flow of the robot's

behavior based on different conditions. In our

application, Switch Case receives a number between

1 and 10 as a signal captured via speech recognition.

The loop of the three questions of the daily scrum was

implemented by combining the Counter box and the

Switch Case box. The Counter box counts up a

variable according to the team members and the

Switch Case box controls the individual loops.

3.3 Experimental Setup

Our study aimed to investigate whether the use of

humour by an education robot NAO would affect the

perception of the robotic facilitator and facilitation,

the learning experience, and the learning outcomes. A

between-subjects, randomized design was chosen to

compare possible effects. All participants signed a

written consent before the study. The study was

conducted at Berlin University of Applied Sciences

in Germany. The study participants were 30

undergraduate students, 56.67% female (17) and

43.33% male (13). The age distribution was 10%

under 20 (3), 69% 20 to 24 (20), 20.7% 25 to 29 (6),

and 3.4% 30 to 34 (1) years old. 93.33% of the

participants (28) had prioe experience in with NAO.

The participants were divided into two groups:

(N) Neutral and (H) Humorous. Each group

comprised of 10 students playing the role of team

members and 5 students playing the role of agile

coaches, resulting in a total of 30 study participants.

Students convened with the teacher and the project

team (authors of the paper) in a seminar room. The

lead researcher (teacher), elucidated the purpose of

the Scrumban simulation, outlined the 90-minute

procedure of the session, obtained written informed

consent, addressed inquiries, randomly assigned

students to either the N or H condition, distributed a

script to each team member, provided an observation

template to each agile coach, and tasked students with

preparing their Kanban cards using post-its.

After this preparation phase, the groups split into

two different rooms, in which two parallel Scrumban

sessions took place, each with a different NAO. Both

groups were supported by two project members: (a)

one operator (ensuring technical implementation on

NAO), and (b) one assistant (helping participants

with any issues).

In each condition, the Scrumban session was

conduced following the same pattern with students

assembling around the Kanban board and NAO

facilitating the session. Both rooms were equipped

with a Kanban board (whiteboard) with three

columns: (1) To-do, (2) In Progress, and (3) Done,

representing a workflow. Each student in the role of a

team member answered the three daily scum

questions and visualised tasks on the Kanban board

using post-its. Students in the role of agile coaches

observed the session. At the end, one person

photographed the Kanban board and students

participated in the online survey. After both sessions,

all participants gathered in one room for the final part,

in which mixed teams (students from the H and N

groups) compared their Kanban boards and agile

coaches provided guidance on improvements.

3.4 Measures

Our primary hypothesis was that the use of humour

the robotic facilitator of Scrumban would result in

higher ratings of the robot’s competence, the quality

of the robotic facilitation and the learning experience

compared to the neutral condition. Our secondary

hypothesis was that the use of humour by NAO would

result in lower ratings of learning outcomes compared

to the neutral condition, as a session without humour

may be perceived as more serious and less distracting.

Our hypotheses were informed by previous studies,

e.g. Belpaeme, et al. (2018) who indicated that social

robots can effectively enhance an educational

Humour in Educational Robots: Investigating the Effects of Humour in a Robot-Led Scrumban Simulation in Business Education

317

experience, Johanson et al. (2020) and

Christoforakos et al. (2021) which showed that humor

can increase perceptions of robot’s competence and

likeability, and Niculescu et al. (2013) who found that

humor can improve task enjoyment and the

perception of a robot. The effects of humour were

nevertheless uncertain, considering findings from

Dybala et al., (2009) and Gorham & Christophel

(1990). The post survey included five scales used to

measure participants’ perceptions of robot-enacted

humour, learning experience, learning outcomes,

facilitator’s competence and facilitation quality. All

items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1=disagree

strongly to 5=agree strongly:

Robot-enacted humour was measured by two

items (“NAO was humorous”; “The amount of

humour was appropriate”). These items were

used as a manipulation check, following the

approach proposed by Johanson et al. (2020).

Learning experience was measured by 22 items

from the scale by Fokides et al. (2021) with 76

items. We applied the shortened version

adapted to HRI by Buchem (2023) and added

two new items on to peer interaction (“I

enjoyed the interaction with my peers”) and the

atmosphere (“I enjoyed the atmosphere of the

session”). Reliability was high, α = .872.

Learning outcomes were measured by two self-

designed items: one about the general outcome

(“The goal of the session was to provide a

hands-on experience of Scrumban. How well

did this session fulfil its goal?), and one about

the robot (“NAO’s facilitation was helpful to

understand a daily meeting.”).

Facilitator’s competence was measured by six

items (competent, confident, capable, efficient,

intelligent, skillful) using the scale was by

Fiske et al. (1999), which was applied by

Christoforakos et al. (2021) to measure

perceived competence of robotic facilitators.

The internal consistency was high, α = .844.

Facilitation quality was measured by three

self-designed items about facilitation

(interesting, motivating, entertaining). The

internal consistency was good, α = .787.

4 RESULTS

Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS

v29 using the five scales described above.

Robot-enacted Humour (HU): A chi-square test

showed that more participants in the H condition

rated the robot as highly humorous with a 4-5 points

(7/15) compared to the N condition (0/15), chi-square

= 13.059, p < 0.05. More participants in the H

condition rated the amount of humour as appropriate

with a 4-5 points (8/15) compared to the N condition

(0/15), chi-square = 12.952, p < 0.05. 17/30 students

in both conditions rated the robot as fairly humorous

with 3 points.

Learning Outcomes (LO): A chi-square test

showed that an equal number of participants in both

conditions rated the general outcome with a 4-5

points (12/15), chi-square = 1.950, p > 0.05. 16/30

students in both conditions rated the first outcomes

with 4 points. There were no ratings of 1 (lowest).

There was a slight, but not significant, difference in

ratings of the second outcome. Contrary to

expectations, the 4-5 point rating in the H condition

(9/15) was more frequent compared to the N

condition (7/15), chi-square = 2.726, p > 0.05. 13/30

students (N and H) rated this outcome with 4 points.

Learning Experience (LX): The comparison of

mean values for 22 items of the LX scale showed that

in both conditions students could equally forget about

time (M=3.60). The H group got higher ratings for 14

out of 22 items, which were related to positive aspects

such as having fun (M=3.13 vs. M=3.00), atmosphere

(M=3.73 vs. M=3.53), focus (M=3.40 vs. M=3.33),

curiosity (M=3.40 vs. M=2.60), knowledge (M=2.87

vs. M=2.80), sense of control (M=3.60 vs. M=3.40),

motivation (M=3.40 vs. M=3.13), feeling successful

(M=3.73 vs. M=3.27), readiness to apply what was

learned (M=4.33 vs. M=3.87), ease to learn (M=3.67

vs. M=3.47), and negative aspects such as complexity

(M=4.33 vs. M=3.80) and frustration (M=1.67 vs.

M=1.53). The N group got higher ratings for 8 out of

22 items, which were related to negative aspects such

as feeling bored (M=2.33 vs. M=2.27), and positive

aspects such as enjoyment (M=2.40 vs. M=2.33),

feeling competent (M=2.07 vs. M=1.60), and peer

interaction (M=2.73 vs. M=2.53).

Facilitator’s Competence (FC): The robotic

facilitator was rated as more confident (M=4.00 vs.

M=3.37), capable (M=3.13 vs. M=3.00), efficient

(M=2.80 vs. M=2.40), intelligent (M=3.33 vs.

M=3.00), skillful (M=3.13 vs. M=2.93) but less

competent (M=3.07 vs. M=3.40) in the H condition.

Facilitation Quality (FQ): Facilitation in both

conditions was perceived as motivating (M=2.87), but

more entertaining (M=4.07 vs. M=4.00) and less

interesting (M=3.33 vs. M=3.40) in the H condition.

Scale Scores: The comparison of mean values for

scale scores revealed slightly lower ratings in the N

condition for the FC scale (M = 3.07 vs. M = 3.24),

and the LX scale (M = 3.03 vs. M = 3.20). The FQ

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

318

scale was slightly higher in the N condition (M = 2.73

vs. M = 2.59) (Figure 2). Independent samples T-tests

yielded no significant differences, neither for single

items nor for scale scores).

Figure 2: Ratings in the N and H conditions for aggregated

scale scores. (Error bars represent the standard error).

Independent samples T-tests related to gender

differences revealed one statistically significant result

for the LX6 item “I felt frustrated” (p = 0.016).

Female students rated this item significantly lower

(M = 1.35, SD = .606) compared to male students (M

= 1.92, SD = 1.256). Frustration was higher in the H

condition (M=1.67 vs. M=1.53). The H group had

more males (n=9) compared to the N group (n=4). In

the H condition, 3 out of 9 males indicated high levels

of frustration with a 3-5 point rating, while females

chose only low ratings of 1-2. These differences were

not significant. Correlation between LX6 and HU was

not significant.

Qualitative results: Responses to an open-ended

question seeking students' recommendations

regarding the integration of robot-enacted humour,

revealed that the majority of students advocated for

the inclusion of robot-enacted humour, emphasising

the capacity of humour to create a more enjoyable and

relaxed learning atmosphere. Participants suggestions

exemplify the spectrum of preferences of robot-

enacted humour. Students’ recommendations fall into

five main categories: (1) Balance: create a balance

between humorous and serious, learning setting. A

robot should be relaxed and funny, but at the same

time focused; (2) Speed: design quick interactions,

robot’s jokes should strive for brevity; (3) Variety:

use a mix of varied conversational humour; (4)

Authenticity: robot’s humour should feel authentic;

(5) Customisation: tailor robot's humour to

educational objectives, e.g. lighthearted remarks for a

relaxed atmosphere, and more extravagant remarks

for grabbing the attention.

5 DISCUSSION

The research question was: How will the use of

humour by an educational robot affect students’

perceptions of the robotic facilitator and robot-led

facilitation, as well as students’ learning experience,

and learning outcomes? Our results, specifically the

absence of statistically significant differences

between both conditions, indicate that the use of

humour by NAO did not significantly affect students’

perceptions of the learning experience (LX), learning

outcomes (LO), facilitator’s competence (FC) nor

facilitation quality (FQ). The ratings of robot-enacted

humor in both conditions indicate that more

participants found the robot highly humorous in the

humorous condition compared to the neutral one,

highlighting the effectiveness of our humor

manipulation in influencing participants' perceptions.

Results related to the Learning Experience (LX)

showed that while students in the humorous condition

had more fun, liked the atmosphere of the session

more, felt more motivated, more curious, more

focused, more successful, more in control, learned

more and were more ready to apply what they

learned, they also perceived the humorous sessions as

more complex and they felt more frustrated.

Participants in the neutral condition felt more bored

but also more competent, and they enjoyed the

session and the peer interaction more. High ratings of

learning outcomes in both conditions indicate that

students gained a good hands-on experience and a

good understanding of Scrumban.

High ratings of facilitator’s competence in the

humorous condition for 5 out of 6 items of the FC

scale indicate that the addition of humour enhanced

the perception of NAO as a confident, capable,

efficient, intelligent and skillful facilitator of the

session. As shown by Christoforakos et al. (2021),

perceived competence of a robot facilitator may be

moderated by perceived anthropomorphism. Future

studies could explore this moderating effects.

Our study uncovered a significant gender

difference, with male students reporting higher levels

of frustration compared to females, with slightly

higher levels of frustration in the humorous condition.

This discrepancy could indicate potential gender-

specific implications of the humor style employed in

our study. Building upon findings from Wu et al.

(2016), who showed that males tend to prefer

aggressive, negative humor, and females empathetic,

positive humour, it is possible that positive humor

applied in our study in some way moderated gender-

specific frustration. However, gender differences in

frustration may stem from a range of other factors,

Humour in Educational Robots: Investigating the Effects of Humour in a Robot-Led Scrumban Simulation in Business Education

319

such as technical issues in speech recognition by

NAO or other factors not captured by the study.

Nevertheless, it is advisable to consider gender-

related humour preferences when designing robot-

enacted humour in future studies.

Finally, iconic examples from the entertainment

industry (including films, TV shows, and games)

such as Star Wars, The Jetsons, and The Hitchhiker's

Guide to the Galaxy demonstrate how humour can be

incorporated in robotic characters. By drawing

insights from these cultural references, researchers

can explore which types of humour applied in

educational robots resonate with learners.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Robot-enacted humour has been studied mainly

independent of context and in isolation of social

meaning (Stoll, Jung & Fussell, 2018). This study

contributes to this field of research by embedding

robot-enacted humour in a specific educational

context. Our investigation into the impact of humour

in a robot-led facilitation of a Scrumban session with

undergraduate business students led us to the

conclusion that even though the incorporation of

humour did not yield statistically significant

differences, the results suggest that humour may

affect some aspects of the learning experience.

It is important to acknowledge limitations of our

study, namely a small sample size, one vs. multiple

sessions, the absence of baseline measurements and

pre-study ratings of humour. Our results cannot be

generalised, as the type and quality of the humour

affects the results of the study. Further calibration and

improvement of humorous elements is needed to

elicit valid data on the effects of humor on learning

from an external and ecological point of view. Future

research would benefit from collecting ratings from

learners before the study and choosing humorous

elements that appeal to specific learners.

While our study provides valuable insights into a

specific application of robot-enacted humour and

demonstrates the feasibility and acceptability of

"humoroids" in business education, further research

is needed to tailor the choice of humor to different

audiences and contexts. Another contribution of our

study is the collection of qualitative data with

recommendations for designing robot-enacted

humour, which can be inform future studies.

Future studies could possibly apply mixed

methods approaches with in-depth interviews to

explore nuanced perceptions of robot-enacted

humour, include larger samples and longitudinal

designs to provide more robust insights into the

potential impact of robot-enacted humour on

learning, also addressing novelty effects. Research

should also explore contextual factors, possible

cultural and gender differences, and social dynamics

in the classroom, e.g. group cohesion. Future studies

could compare effects of different types of humour,

and manipulate the number of humorous elements to

explore how the quantity of humour may affect the

difference facets of the learning experience.

REFERENCES

Alqudah, M., Razali, R. (2018). An Empirical Study of

Scrumban Formation based on the Selection of Scrum

and Kanban Practices. International Journal on

Advanced Science. In Engineering and Information

Technology. Vol. 8, No. 6, 2315-2322,

DOI:10.18517/ijaseit.8.6.6566

Anwar, S., Bascou, N. A., Menekse, M., Kardgar, A.

(2019). A Systematic Review of Studies on Educational

Robotics. In Journal of Pre-College Engineering

Education Research (J-PEER), 9(2), Article

2.https://doi.org/10.7771/2157-9288.1223

Bechade, L., Duplessis, G. D., Devilliers, L. (2016).

Empirical study of humour in social human–robot

interaction. In Proceedings of the International

Conference on Distributed, Ambient, and Pervasive

Interactions, 305–316.

Belpaeme, T., Kennedy, J., Ramachandran, A., Scassellati,

B., Tanaka, F. (2018). Social robots for education: a

review. In Sci. Robot. 3, eaat5954.

Buchem I. (2023). Scaling-Up Social Learning in Small

Groups with Robot-Supported Collaborative Learning

(RSCL): Effects of Learners’ Prior Experience in the

Case Study of Planning Poker with the Robot NAO. In

Applied Sciences, 13, 4106.

Buchem, I., Baecker, N. (2022). NAO Robot as Scrum

Master: Results from a scenario-based study on

building rapport with a humanoid robot in hybrid higher

education settings. In Salman Nazir (Ed.) Training,

Education, and Learning Sciences. AHFE (2022), 59,

65–73. AHFE International, USA.

Buchem, I., Christiansen, L., Glißmann-Hochstein, S.

(2023). Planning Poker Simulation with the Humanoid

Robot NAO in Project Management Courses. In:

Balogh, R., Obdržálek, D., Christoforou, E. (eds)

Robotics in Education. RiE 2023. Lecture Notes in

Networks and Systems, vol 747. Springer, Cham.

Christoforakos L., Gallucci A., Surmava-Große T., Ullrich

D., Diefenbach S. (2021) Can Robots Earn Our Trust

the Same Way Humans Do? A Systematic Exploration

of Competence, Warmth, and Anthropomorphism as

Determinants of Trust Development in HRI. In

Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 8:640444

Dybala, P., Ptaszynski, M., Rzepka, R., & Araki, K. (2009).

Humoroids: conversational agents that induce positive

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

320

emotions with humor. AAMAS '09 Proceedings of The

8th International Conference on Autonomous Agents

and Multiagent Systems, 2, 1171-1172.

Dynel, M. (2009). Beyond a joke: Types of conversational

humour. In Language and Linguistics Compass, 3,

1284–1299.

Fiske, S. T., Xu, J., Cuddy, A. C., Glick, P. (1999).

(Dis)respecting versus (Dis)liking: Status and

interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of

competence and warmth. In Journal of Social Issues,

55(3), 473-489.

Fokides, E., Kaimara, P., Deliyannis, I., Atsikpasi, P.

(2021). Development of a scale for measuring the

learning experience in serious games. Preliminary

results. In Digital Culture & Audiovisual Challenges:

Interdisciplinary Creativity in Arts and Technology.

Gittens, C.L. (2021). Remote HRI: a Methodology for

Maintaining COVID-19 Physical Distancing and

Human Interaction Requirements in HRI Studies. In

Information Systems Frontiers, 1–16.

Gorham J., Christophel D.M. (1990). The relationship of

teachers’ use of humour in the classroom to immediacy

and student learning. Communication Education. 39(1),

46-62.

Gubenko A, Kirsch C, Smilek JN, Lubart T, Houssemand

C. (2021). Educational Robotics and Robot Creativity:

An Interdisciplinary Dialogue. Frontiers in Robotics

and AI; 8:662030.

Johanson, D. L. et al. (2020). Use of Humour by a

Healthcare Robot Positively Affects User Perceptions

and Behavior. In Technology, Mind, and Behavior,

1(2).

Li, Y., Ishi, C.T., Ward, N.G., Inoue, K., Nakamura, S.,

Takanashi, K. and Kawahara, T. (2017), Emotion

recognition by combining prosody and sentiment

analysis for expressing reactive emotion by humanoid

robot. In Asia-Pacific Signal and Information

Processing Association Annual Summit and

Conference (APSIPA ASC), 1356–1359.

Lovorn, M.G., Holaway, C. (2015). Teachers ’perceptions

of humour as a classroom teaching, interaction, and

management tool. In The European Journal of Humour

Research, 3, 24-35.

Lynch, O. H. (2002). Humorous communication: Finding a

place for humour in communication research. In

Communication Theory, 4, 423–445.

Merdan, M., Lepuschitz, W., Koppensteiner, G., Balogh, R.

(Eds.). (2016). Robotics in education research and

practices for robotics in STEM education. Springer.

Mirnig, N., Stadler, S., Stollnberger, G., Giuliani, M., &

Tscheligi, M. (2016). Robot humour: How self-irony

and Schadenfreude influence peoples rating of robot

likeability. In Proceedings of the 25th IEEE

International Symposium on Robot and Human

Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 166–171.

Mora, R.A., Weaver, S., Lindo, L.M. (2015). Editorial for

special issue on education and humour: Education and

humour as tools for social awareness and critical

consciousness in contemporary classrooms. In The

European Journal of Humour Research, 3, 1-8.

Morrison, M. K. (2008). Using Humour to Maximize

Learning: The Links between Positive Emotions and

Education. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Musiichuk M.V., Gnevek O.V., Musiichuk, S.V. (2018).

Cognitive-Affective Aspect Of Humour Influence On

Development Of Students' Innovative Abilities. In

Proceedings of the International Conference on

Research Paradigm Transformation in Social Sciences

RPTSS 2017, 972-978.

Niculescu, A., van Dijk, B., Nijholt, A., Li, H., See, S. L.

(2013). Making social robots more attractive: The

effects of voice pitch, humour and empathy. In

International Journal of Social Robotics, 5, 171–191.

OECD (2021), OECD Digital Education Outlook 2021:

Pushing the Frontiers with Artificial Intelligence,

Blockchain and Robots, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Omokawa, R., Kobayashi, M. and Matsuura, S. (2019),

Expressing the Personality of a Humanoid Robot as a

Talking Partner in an Elementary School Classroom.

Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction.

Theory, Methods and Tools. In: M. Antona and C.

Stephanidis (eds.) HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, 11572, 494–506, Springer Cham.

Petricioli, L., Fertalj, K. (2022). Agile Software

Development Methods and Hybridization Possibilities

Beyond Scrumban. In 2022 45th Jubilee International

Convention on Information, Communication and

Electronic Technology (MIPRO), 1093-1098.

Samson, А.С., Gross. J.J. (2012). Humour as emotion

regulation: The differential consequences of

negative versus positive humour. Cognition and Emotion.

26(2), 375–384.

Stoll, B., Jung, M.F., Fussell, S.R. (2018). Keeping it Light:

Perceptions of Humour Styles in Robot-Mediated

Conflict. In IEEE International Conference on Human-

Robot Interaction.

Suls, J. (1983). Cognitive Processes in Humour

Appreciation. In: McGhee, P.E., Goldstein, J.H. (eds)

Handbook of Humour Research. Springer, New York.

Wu, C.-L., Lin, H.-Y., & Chen, H.-C. (2016). Gender

differences in humour styles of young adolescents:

Empathy as a mediator. In Personality and Individual

Differences, 99, 139–143

Humour in Educational Robots: Investigating the Effects of Humour in a Robot-Led Scrumban Simulation in Business Education

321