Usability and User Experience Questionnaire Evaluation and Evolution

for Touchable Holography

Thiago Prado de Campos

1,2 a

, Eduardo Filgueiras Damasceno

1 b

and Natasha M. C. Valentim

2 c

1

Universidade Tecnol

´

ogica Federal do Paran

´

a, Brazil

2

Universidade Federal do Paran

´

a, Brazil

Keywords:

Questionnaire, Touchable Hologram, Holography, Expert Evaluation, Validation, Usability, User Experience.

Abstract:

Augmented and Mixed Reality enables applications where users engage in natural hand interactions, simu-

lating touch, termed touchable holography solutions (THS). These applications are achievable through head-

mounted displays and are helpful in training, equipment control, and entertainment. Usability and User eXpe-

rience (UX) evaluations are crucial for ensuring the quality and appropriateness of THS, yet many are assessed

using non-specific technologies. The UUXE-ToH questionnaire was proposed and subjected to expert study

for content and face validity to address this gap. This study enhances questionnaire credibility and acceptance

by identifying clarity issues, aligning questions with study theory, and reducing author-induced bias, offering

an effective and cost-efficient approach. The study garnered numerous contributions that were analyzed qual-

itatively and processed to refine the questionnaire. This paper introduces the UUXE-ToH in its initial version,

details expert feedback analysis, outlines the methodology for incorporating suggestions, and presents the en-

hanced version, UUXE-ToH v2. This evidence-based process contributes to a better understanding of usability

and UX evaluation in the THS context. UUXE-ToH can impact the quality of life of users of solutions applied

to education, health, and entertainment by helping develop better products.

1 INTRODUCTION

Touchable holography, an innovative technology fa-

cilitating gesture and mid-air touch interaction by

projecting digital content into the natural environ-

ment (Kervegant et al., 2017), is experiencing rapid

evolution alongside advancements in Augmented

Reality (AR) and Mixed Reality (MR). The Mi-

crosoft Hololens™ and Meta Quest3™ exemplify this

progress, enabling users to engage with holograms

through hand gestures and contributing to the emer-

gence of Touchable Holographic Solutions (THS).

This paradigm shift eliminates traditional screens, in-

troducing novel approaches like head-mounted dis-

plays and touch interactions without physical feed-

back. Regardless of the display technology, holo-

grams emulate real-world entities, responding to

gaze, gestures, and voice commands (Microsoft Inc,

2022). The seamless integration of synthetic elements

blurs the boundary between the real and virtual worlds

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1038-4004

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6246-1246

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6027-3452

in AR and MR, enhancing user experiences. Touch-

able holograms find diverse applications, from equip-

ment control to entertainment, utilizing natural and

flexible interactions facilitated by gesture-based inter-

faces, encompassing pointing, pantomimic, and ma-

nipulation gestures (Aigner et al., 2012). Hologra-

phy’s absence of haptic feedback is a notable draw-

back, but ongoing efforts to enhance audiovisual feed-

back and explore air-based solutions show promise

for natural touch simulation.

Ensuring the effectiveness of THS demands a

comprehensive evaluation, focusing on both Usabil-

ity and User eXperience (UX). Usability assesses the

ease of use (Nielsen, 2012), effectiveness, efficiency,

and satisfaction of using an artifact with a specific

purpose and context (ISO, 2018). UX is a person’s

quality of experience when interacting with the in-

teractive artifact (Hassenzahl, 2011). UX focuses on

user preferences, perceptions, emotions, and physical

and psychological responses that occur before, dur-

ing, and after use (Bevan et al., 2015).

Recognizing the absence of dedicated evaluation

technologies for THS, a Systematic Mapping Study

(SMS) conducted by Campos et al. (2023) high-

Campos, T., Damasceno, E. and Valentim, N.

Usability and User Experience Questionnaire Evaluation and Evolution for Touchable Holography.

DOI: 10.5220/0012564100003690

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024) - Volume 2, pages 449-460

ISBN: 978-989-758-692-7; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

449

lighted the reliance on multiple generic tools, such

as the System Usability Scale (SUS) (Brooke, 1996)

and User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) (Laugwitz

et al., 2008). Most THS studies used at least three

existing questionnaires. However, these don’t fully

cover unique aspects of AR/MR, like immersion and

presence. Combining multiple evaluation technolo-

gies may confuse users and cause overlapping of as-

sessed aspects. To address this gap, we proposed

the “Usability and UX Evaluation in Touchable Holo-

grams (UUXE-ToH)” questionnaire, composed of ob-

jective sentences and open-ended questions to cover

the evaluation of the main aspects of usability and

UX, including dimensions of AR/MR.

New technologies should undergo initial stud-

ies to identify strengths, limitations, and challenges,

contributing to technique refinement before industry

adoption (Shull et al., 2001). For survey question-

naires, ensuring validity and reliability is crucial for

assessing their viability, enabling use in future case

studies, and potentially applying them in final solu-

tions. To affirm the UUXE-ToH suitability for as-

sessing THS usability and UX, a content and face

validation study involving 13 experts was performed.

This study validated the questionnaire and provided

valuable insights for refinement, including enhanc-

ing question clarity, sentence structure, and additional

guidance for future evaluators. Therefore, this study

is motivated by the central research question: How

can the UUXE-ToH questionnaire be refined and im-

proved based on expert qualitative feedback?

Feedback meetings with experts were recorded

and transcribed, with participant comments on the

evaluation form and notes within UUXE-ToH joined

to the transcript. Qualitative analysis followed the

first two steps of the Grounded Theory (GT) method

proposed by Corbin and Strauss (2014) , encompass-

ing open coding (1) and axial coding (2). The first

step involved categorizing data based on each par-

ticipant’s response, while the second grouped codes

based on their properties and relationships, forming

categories representing their characteristics. Notably,

selective coding was omitted, as this study focused

on the initial validation and improvement of UUXE-

ToH, with open and axial coding proving sufficient to

comprehend experts’ opinions.

This paper unfolds the evolution of the UUXE-

ToH questionnaire, from its inception to the second

version, shaped by expert insights. Beyond detail-

ing the questionnaire’s evolution, the paper addresses

a critical gap in touchable holography evaluation. It

brings the refined UUXE-ToH and a methodologi-

cal approach that enriches our understanding of Aug-

mented and Mixed Reality user interactions.

The paper’s subsequent sections include a re-

view of related work (Section 2), an overview of the

UUXE-ToH questionnaire (Section 3), a detailed ac-

count of the content and face validation study with ex-

perts (Section 4), a presentation of suggestions from

the study (Section 5), a demonstration of the process-

ing of expert suggestions (Section 6), and an introduc-

tion to the second version of the UUXE-ToH ques-

tionnaire (Section 7). The final considerations are

presented in Section 8.

2 RELATED WORK

Ensuring the accuracy and replicability of research re-

sults depends heavily on the validity and reliability

of the instruments, primarily questionnaires. Validity,

covering face, content, construct, and criterion types,

focuses on measuring what the instrument intends to

measure, while reliability, including equivalence, sta-

bility, and internal consistency, ensures applicability

(Bolarinwa, 2015). Content validity is crucial to en-

sure the questionnaire items’ relevance, representa-

tiveness, and comprehensiveness concerning the con-

struct measured (Koller et al., 2017). Face valid-

ity addresses the appearance and initial acceptability

of the questionnaire, identifying clarity, format, and

style issues (DeVellis and Thorpe, 2022). Content

and face validation are inseparable, and their results

allow adjustments to the questionnaire before moving

on to other validation stages (Costa, 2021). A liter-

ature search identified validity and reliability studies

for questionnaires assessing usability, UX, or dimen-

sions in AR/MR environments. Below, we highlight

selected questionnaires and their associated studies.

The Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of Use

Questionnaire (USE), developed by Lund (2001), was

submitted to a study with 151 participants aimed to

evaluate your psychometric properties (Gao et al.,

2018). The USE, consisting of 30 items on a 7-

point Likert scale, measures usability across four di-

mensions: usefulness, ease of use, ease of learning,

and satisfaction. The participants assessed Microsoft

Word and Amazon.com using the USE and the SUS.

The study revealed high reliability for the overall USE

score (Cronbach’s alpha = .98). Validity was estab-

lished through significant correlations between USE

dimensions and SUS scores (r between .60 and .82,

p <.001). A factor analysis unveiled a four-factor

model, deviating from the original.

The UEQ underwent a psychometric evaluation

to establish its validity through two usability studies.

In the first study, 13 participants performed tasks re-

lated to a sales representative scenario. Task-oriented

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

450

aspects (Perspicuity, Efficiency, Dependability) were

expected to negatively correlate with task completion

time, while non-task-related aspects (Novelty, Stimu-

lation) showed no substantial correlation. The study

validated these hypotheses, indicating initial validity

for the questionnaire. In the second study, 16 students

participated in a usability test with tasks in a CRM

system, and correlations between UEQ scales and the

AttrakDiff2 questionnaire were examined. The ex-

pected correlations were confirmed, further support-

ing the UEQ’s validity.

The Presence Questionnaire (PQ) and Immersive

Tendencies Questionnaire (ITQ) were developed to

measure presence in a virtual environment (VE) and

individuals’ tendencies for immersion, respectively.

PQ had 28 items, and ITQ had 29. The questionnaires

underwent evaluation through four experiments in-

volving 152 participants performing tasks in different

VEs. Reliability analyses yielded Cronbach’s Alpha

values of 0.81 for ITQ and 0.88 for PQ. Content valid-

ity was established by deriving PQ items from factors

identified in the literature about presence. Construct

validity was supported by positive correlations with

VE task performance, ITQ scores, and negative corre-

lations with Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ)

scores (Kennedy et al., 1993). Factors were identi-

fied for both questionnaires through cluster analyses.

The statistically derived constructs of the PQ do not

perfectly match the original factors.

This short review underscores the need for im-

proved validation processes to ensure the relevance

of measured constructs. However, based on the pub-

lications found and cited above, no details about the

content and face validation process carried out in the

USE, UEQ, PQ, and ITQ questionnaires were identi-

fied. In response, this article distinguishes the UUXE-

ToH questionnaire by presenting the results of an ex-

pert validation study to confirm its constructs’ suit-

ability and sentences to evaluate THS.

3 UUXE-ToH

The formulation of the UUXE-ToH questionnaire was

a meticulous process, initiated by consciously choos-

ing a questionnaire as the evaluation method. This de-

cision was driven by its practicality, ease of data col-

lection, and impersonal nature (Skarbez et al., 2017).

Drawing on established models for questionnaire de-

velopment, the process prioritized defining constructs

based on theoretical reviews (DeVellis and Thorpe,

2022). Then, the constructs for the questionnaire were

described based on the SMS of Campos et al. (2023)

and an Exploratory Search (Marchionini, 2006) of

common usability and UX aspects in the literature.

This process involved merging usability and UX cri-

teria into a cohesive set, ensuring a comprehensive

evaluation framework.

Initially, based on the exploratory search, 18 as-

pects were carefully defined, covering critical dimen-

sions: Effectiveness, Efficiency, Learnability, Memo-

rability, Error Prevention and Recovery, Controllabil-

ity, Satisfaction, Overall Usability, Pleasure and Fun,

Trustworthiness, Usefulness, Beauty and Aesthetic,

Desirability, Value, Creativity and Novelty, Emo-

tional, Stimulation, and Overall UX. After, based on

essential dimensions of AR/MR environments (Skar-

bez et al., 2021) that were poorly explored in eval-

uation technologies found in the SMS, we intro-

duced into the set two specific aspects, Immersion

and Presence, providing distinct perspectives in eval-

uating THS, resulting in 20 aspects representing the

questionnaire’s constructs. Immersion focused on

the objective enhancement of the manipulation func-

tion (Slater, 2018), while Presence delved into users’

subjective experiences (Berkman and Akan, 2019),

capturing their sense of virtual elements seamlessly

blending into the real world.

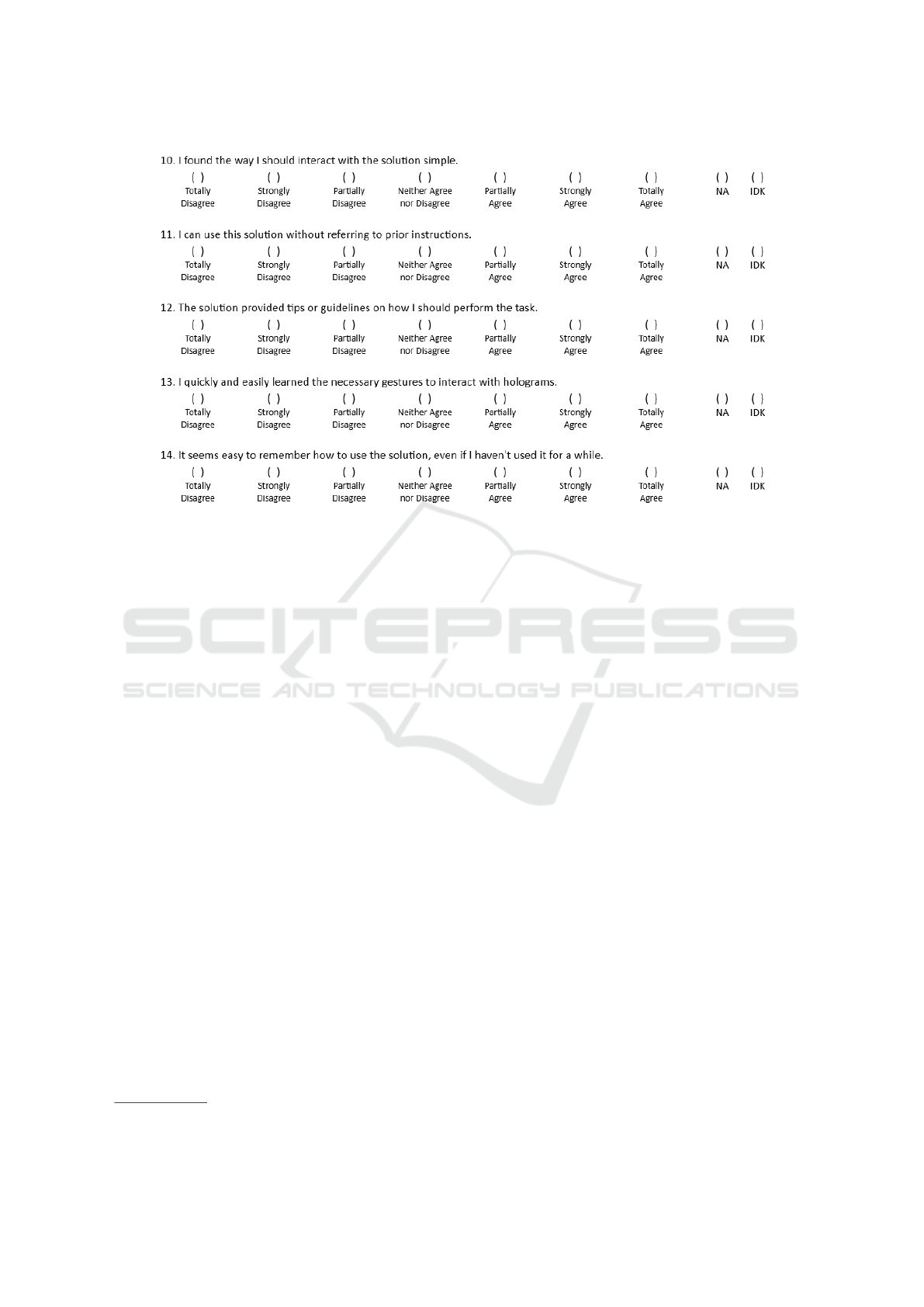

With the constructs set in place, the next phase in-

volved creating an item pool for the questionnaire. A

sample comprising 67 assessment items was gener-

ated to measure the 20 selected constructs (Figure 1).

The process included creating sentences by merging

original formulations with content adapted from iden-

tified questionnaires. The UUXE-ToH questionnaire

adopts a 7-level Likert scale for response accuracy

and enhanced user engagement, providing three gra-

dations for agreement and disagreement. This scale

aligns with established usability assessment question-

naires and ensures a more nuanced and precise re-

flection of respondents’ evaluations (Finstad, 2010).

The inclusion of ”Not Applicable” (NA) and ”I Don’t

Know How to Answer” (IDK) options supply diverse

contexts and user uncertainties.

Additionally, three open-ended questions follow

the objective items, strategically designed to gather

qualitative feedback, allowing users to articulate

their experiences and propose constructive sugges-

tions. The questionnaire deliberately avoids grouping

sentences and labeling constructs, prioritizing user

simplicity and familiarity. The complete UUXE-

ToH questionnaire can be accessed at this link:

https://figshare.com/s/c2bca82c8fe238b392f8.

Usability and User Experience Questionnaire Evaluation and Evolution for Touchable Holography

451

Figure 1: Part of UUXE-ToH v1.

4 VALIDATION STUDY

Approved by the Research Ethics Committee, the

study aimed to analyze the UUXE-ToH through con-

tent and face validation by experts. The study oc-

curred remotely from June to August 2023, involv-

ing experts from Brazilian laboratories and research

groups related to Human-Computer Interaction, Us-

ability, UX, Software Engineering, AR, and MR.

Participants underwent a video instruction call,

receiving information about UUXE-ToH and the

study’s goals. The UUXE-ToH questionnaire and on-

line forms for participant characterization and evalua-

tion were provided. Participants had one to six weeks

to complete the forms for assessment. Afterward,

they participated in a second video call for general

feedback. Electronic forms data were processed and

analyzed using Atlas.ti

1

software and the GT method,

specifically open and axial coding.

Thirteen experts (P1 to P13) holding Ph.D. or

Master’s degrees across diverse academic back-

grounds, including Computer Science, Design, En-

gineering, and Sciences, participated. The majority

were male, with ages ranging from 21 to 60. Pro-

ficiencies included Usability, UX, and experience in

AR/MR. Expertise levels varied, providing a compre-

hensive perspective on the UUXE-ToH questionnaire.

1

https://atlasti.com/

5 QUALITATIVE RESULTS

The qualitative analysis resulted in categories pre-

sented in the following subsections (Figure 2).

5.1 Suggestions for Sentences

This was the biggest category of experts’ feedback.

Therefore, it was divided into subcategories: Rewrit-

ing, Terms Explain or Standardization, Discarding,

Unifying, Modifying or Rethinking, Sorting and

Proximity, Adding New, and Others.

5.1.1 Rewriting

The experts presented many suggestions related to

sentence writing. Overall, recommendations included

substituting complex words with user-friendly al-

ternatives, incorporating examples and explanations,

and improving assertiveness (see comments from P8,

P9, and P7). Additionally, spelling and grammar er-

rors were identified. Criticism and suggestions for

standardization were directed at repeated terms across

sentences (see comments from P1, P2, and P10).

P8 (31-40y, MSc.) “Depending on the type of

user, there should be a definition in parenthe-

ses of a ‘mixed environment.’ ”

P9 (51-60y, phD.) “In 23, the ‘mixed environ-

ment’ concept is introduced. It is worth think-

ing about whether users can easily understand

it. Consider using a less specific description.”

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

452

Figure 2: TreeMap of expert’s feedback that provides improvement actions in UUXE-ToH.

P7 (31-40y, MSc.) “Here, ‘I did not make

mistakes when trying (...).’ I suggested that

instead of ‘mistake,’ use the word ‘difficulties’

so the user does not feel frustrated.”

P1 (21-30y, phD.) “Some terminology issues.

For example, sentence 2 says, ‘The solu-

tion recognized all my gestures and touches

in holograms.’ Then, sentence 4 says, ‘The

holography always correctly selected the ob-

ject I wanted to interact with.’ So, it’s stan-

dardizing, right?”

P2 (41-50y, phD.) “Is holography the same

thing as a hologram? (...) better standardize.

(...) will the user know the difference?”

P10 (21-30y, MSc.) “Regarding standardiza-

tion, I think it would be interesting to adopt

a term. For example, if you adopt a ”holo-

graphic solution.” So, use ”holographic solu-

tion” in the entire questionnaire. I saw a ”so-

lution.” I also saw ”interactive system.””

5.1.2 Discarting

Here, we group suggestions for discarding sentences

for various reasons. For example, some experts con-

sidered sentence 20, related to the Overall Usability

construct, unnecessary as others already helped mea-

sure ease of use (see comments from P7 and P10).

Another expert warned that sentence 31, related to

lighting conditions, was not something the end user

should evaluate (see P12’s comment). There was also

a suggestion to remove sentences related to auditory

feedback (see P3’s comment).

P7 (31-40y, MSc.) “I found the holographic

solution easy to use. In my opinion, there

would be no reason to keep question 20. It

seems to me that questions 10 and 20 are very

similar. I would leave just one of them.

P10 (21-30y, MSc.) “Perhaps sentence 20

could be excluded to shorten the question-

naire, as it may already be included in others.

P12 (51-60y, phD.) “Sentence 41 doesn’t

seem to provide very relevant information for

anyone...”

P3 (31-40y, phD.) “You could eliminate some

sentences. Depending on the experiment,

there is no sound.”

5.1.3 Unifying

This category groups explicit suggestions to unify or

merge sentences. An expert suggested unifying sen-

tences 5 and 6 because they relate to time (see P5’s

comment). Another suggested combining sentences

40 and 41 related to innovation and modern resources

(see P7’s comment). Another indicated that sentences

55 and 56 are one because pleasant and fun could be

considered a single user desire (see P12’s comment).

Usability and User Experience Questionnaire Evaluation and Evolution for Touchable Holography

453

P5 (31-40y, MSc.) “As it is about time, think

sentences 5 and 6 could be just one.”

P7 (31-40y, MSc.) “The sentences 40 and 41

could be transformed into one. Innovative,

technological... This could become a single

sentence, for have fewer questions, okay?”

P12 (51-60y, phD.) “I think it could be just

one sentence. Does someone want to have fun

with the interaction or want it to be pleasant?

Does anyone have fun with the mouse?”

5.1.4 Modifying Structure or Rethinking

Suggestions were made to modify the structure of cer-

tain UUXE-ToH sentences. For example, someone

suggested that sentence 38 become an open question

(see P8’s comment). Another suggestion in this re-

gard was to replace sentences about Emotions with

an open question (see P7’s comment). For sentence

54 concerning discomfort, an expert recommended

adding an empty field to allow the user to describe the

type of discomfort experienced (see P3’s comment).

P8 (31-40y, MSc.) “This question will be con-

ditioned on the user knowing other tools to

compare. It gains more when asked openly.”

P7 (31-40y, MSc.) “Here is a sequence of sen-

tences related to feelings. Instead of having

these, there could be a question that asks what

sensations he felt when using it.”

P3 (31-40y, phD.) “In sentence 54, the user

would place it on the scale and open a field to

report this discomfort.”

5.1.5 Sorting and Proximity

Suggestions were made to rearrange specific sen-

tences. For example, concerning sentences for Learn-

ability, someone suggested that sentences 11 and 12

be reversed in order of presentation (see P8’s com-

ment). It was also suggested that sentence 23 be

brought closer to other sentences about gestures (see

P4’s comment).

P8 (31-40y, MSc.) “In item 11, ”I can use it”

or ”I was able to use it” without prior instruc-

tions would be manual, which is different from

item 12, tips and guidance. Maybe change the

order of 12 and 11, ask if it was presented, and

then if it needed to be used.”

P4 (51-60y, phD.) “Shouldn’t sentence 23,

(...), be close to the gestures items?”

5.1.6 Adding New Sentences

Experts also suggested new sentences for UUXE-

ToH. For example, it was suggested that more sen-

tences be added to the Memorability construct (see

P6a’s comment). Another sentence was indicated to

the Immersion construct to evaluate problems of pass-

ing through the holographic object (see P3’s com-

ment). Also, a direct and objective sentence was sug-

gested to assess Satisfaction (see P6b’s comment).

P6a (21-30y, BS.) “I think you only have one

sentence about memorization. There could be

at least one more sentence. For example: ‘I

can easily remember one or more elements of

the solution’ or ‘It is easy for me to remember

the sequence of steps to use the solution.’ ”

P3 (31-40y, phD.) “If you crossed the line

when interacting. Regarding passing through

the object. It’s because sometimes we get con-

fused by distance. Suppose you want to touch

the object and pass by it.”

P6b (21-30y, BS.) “There could be a straight-

forward satisfaction question. ‘I was satisfied

using the solution.’ ”

5.2 Suggestions About Structure and

Presentation

In this category, we have included suggestions related

to questionnaire structure (like constructs, scale, and

answer options) and related to the presentation (like

grouping, labeling, and sorting). The following sub-

categories were created to facilitate the analysis.

5.2.1 Constructs Set

This subcategory encompasses the comments about

the suitability of the constructs for evaluating SHTs.

One expert proposed excluding Overall Usability and

General UX constructs, suggesting they could be

assessed through other aspects of the questionnaire

(see P10’s comment). Additionally, a recommen-

dation was made to introduce a dedicated Comfort

construct (see P2’s comment) covering existing sen-

tences, given its importance in interactions involving

arm movement and wearable devices.

P10 (21-30y, MSc.) “Could general usabil-

ity not be obtained from the usability subcon-

structs? (...) wouldn’t extracting the general

UX from the other constructs be better?”

P2 (41-50y, phD.) “I believe this sentence (54)

is much more linked to a dimension of com-

fort. This item is close to an item on the effi-

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

454

ciency construct, about physical fatigue. Per-

haps this sentence and the 7 one could be

grouped into a separate dimension, such as

‘Comfort.”’

5.2.2 Labeling Constructs and Sorting

Experts were divided regarding labeling groups of

sentences to identify the constructs assessed by the

questionnaire. Some thought that labeling was bene-

ficial to the end user, and those who believed that it

could overload the user with terms that the user is not

familiar with. Some suggested that sentences could

be grouped into themes (not necessarily constructs),

and these groups identified with words that are easy

for the end user to understand (See comments from

P8 and P9). Grouping and labeling could also allow

other researchers to remove parts of UUXE-ToH that

they do not consider necessary for their evaluation

context (see P12’s comment). Regarding the order of

presentation of the constructs, the majority did not see

any problems with the proposed order. However, an

expert reinforced that pragmatic aspects should come

before hedonic aspects (See P10’s comment).

P8 (31-40y, MSc.) “I think maybe grouping

them into themes.”

P9 (51-60y, phD.) “Many sentences could be

grouped by subject.”

P12 (51-60y, phD.) “You should make these

divisions of the questionnaire more explicit.

People can remove parts of the questionnaire

if they are not interesting.”

P10 (21-30y, MSc.) “I recommend to group

the pragmatic and then the hedonic aspects.”

5.2.3 Likert Scale and Answer Options

This category grouped suggestions related to users’

response options. For example, about the Likert scale,

one of the researchers suggested that the manual for

using UUXE-ToH must contain instructions on how

the results should be analyzed, warning not to use the

average (see P10’s comment). Another expert opined

that the IDK option could serve as an escape for the

respondent to avoid expressing their opinion on a sen-

tence (see P1’s comment).

P10 (21-30y, MSc.) “Regarding the Likert

scale, there should be a guide to indicate use

median and not average.”

P1 (21-30y, phD.) ‘Sometimes, he will dis-

agree with something, but instead of disagree-

ing, he responds IDK so as not to disagree,

and ends up biasing the answer. It can be an

escape valve for the user. So it would be best

to consider whether you will keep it.”

5.3 Considerations About Sentences

In this category, comments that presented positive or

negative considerations about specific sentences, re-

inforcing their relevance or indicating a problem with

the sentence, were grouped. For example, sentence

06 was considered very useful despite having specific

applicability (see P8’s comment). Regarding sentence

19, one of the experts pointed out that the loss of mo-

bility may not impact carrying out the task (see P4’s

comment). In sentence 50, the term ”interesting” was

considered too vague by one of the experts (see P12a’s

comment). This same expert found it difficult to dif-

ferentiate surprise from admiration in sentences 66

and 67 (see comment P12b). These considerations,

although not explicit suggestions are essential for de-

cisions to be made with the sentences to which they

are related.

P8 (31-40y, MSc.) “In sentence 6, there is a

need for specific practical applicability. But it

is very useful!”

P4 (51-60y, phD.) “This may not have influ-

enced the execution of the task... review the

focus and importance of the question.”

P12a (51-60y, phD.) “Interesting is too vague

a term to ask.”

P12b (51-60y, phD.) “I don’t know how to

differentiate surprise from admiration well in

this context.”

5.4 Perceptions of Similar Sentences

The experts also sought to identify whether the sen-

tences were similar and whether they seemed to eval-

uate the same thing. In this sense, several sentences

were highlighted, such as sentences 2 and 28 (see P3’s

comment), 4 and 35 (see P8’s comment), and 9 and

10 (see P5’s comment). An expert also thought that

sentence 20 was a synthesis of sentences 9 to 14 (see

P11’s comment).

P3 (31-40y, phD.) “28 is similar to 2.”

P8 (31-40y, MSc.) “4 I found similar to 35.”

P5 (31-40y, MSc.) “9 and 10 are similar.”

P11 (41-50y, phD.) “At twenty, I found the

holographic solution easy to use. It seemed

like a synthesis of what had already been con-

sidered in 9 to 14.”

Usability and User Experience Questionnaire Evaluation and Evolution for Touchable Holography

455

5.5 Doubts

5.5.1 Doubts About Specific Sentences

Certain sentences raised concerns for potential con-

fusion among end users or generated doubts among

experts due to poorly chosen words. For example,

in sentence 5, “little time” raised concerns (see P7a’s

comment). In sentence 27, “occlusion” also raised

doubts (see comments from P8 and P1). Sentence 51

also caused doubts for some experts, as the person

would have already used the solution when filling out

the questionnaire (see comments from P7b and P11).

P7a (31-40y, MSc.) “What would be a short

time? (...) what is considered a short time?

Wouldn’t it be better to put the time allocated

for the activity?”

P8 (31-40y, MSc.) “Occlusion was a difficult

term that I had to look for meaning.”

P1 (21-30y, phD.) “I don’t know what occlu-

sion is.”

P7b (31-40y, MSc.) “This question (51), I

don’t quite understand if it’s for people who

have never used this solution. I was a little

confused because I understand that the person

has already used this solution, so they actually

wouldn’t like to be able to use it. Maybe they

can use it in another situation.”

P11 (41-50y, phD.) “I was wondering if it

made sense because here he is already using

it, right? So perhaps, if he would like to use

this solution frequently or daily, it would be

more in that direction.”

5.5.2 General Doubts

This category comprises experts’ concerns applica-

ble to multiple sentences or the entire questionnaire.

The primary issue is using varying terms, occasion-

ally synonymous with holographic solutions, lead-

ing to potential confusion (see comments from P2

and P11). Similarly, the terms “task” and “activities”

also raised doubts about their meaning (see P3’s com-

ment). There was also a doubt whether Learnability

was about the activity to be carried out or about the

solution (see P10’s comment).

P2 (41-50y, phD.) “I was unsure between

holography and hologram (...) Is holography

the same as hologram? Will the user know the

difference?”

P11 (41-50y, phD.) “(...) Sometimes, you use

‘the holographic solution’; Others, just ‘the

solution.’ Also, you use ‘hologram,’ and it

seems to me in the sense of replacing the ‘so-

lution’ term. This might confuse those who are

using it.”

P3 (31-40y, phD.) “Some sentences said ‘type

of task,’ and others said ‘tasks.’ Others, ‘ac-

tivities.’ Could it be a task that has multiple

actions? Could it be a sequence of tasks or

actions? It’s just a matter of writing. Some

sentences are in the singular, and others are in

the plural. Make it clear to the participant.”

P10 (21-30y, MSc.) “Is Learnability a con-

cept related to the holographic solution or the

activities? What are you trying to measure

learnability?”

5.6 Suggestions About Open Questions

The first question was what received the most sug-

gestions. Experts recommended adding a neutral an-

swer option or a scale to enhance respondent flexibil-

ity. (see comment from P2a). It was also suggested

that this question be divided into positive and nega-

tive reports (see P2b’s comment). In question 3, the

experts suggested adding comments and criticisms to

the question and changing the pronoun to allow opin-

ions about other people’s experiences (see comments

from P3 and P8).

P2a (41-50y, phD.) “I would leave the ‘neu-

tral’ option. Another possibility would be to

use a 7-point scale (e.g., very negative, neg-

ative, somewhat negative, neutral, somewhat

positive, positive, very positive). This would

even make it possible to test the correlation

between the overall experience and the other

dimensions.”

P2b (41-50y, phD.) “It would be worth divid-

ing it into two questions: ’What was positive?’

and ’What was negative?’. This way, there

would be no risk of people talking only about

the positive or negative points.”

P3 (31-40y, phD.) “In the last question, you

could mention comments and criticisms too.”

P8 (31-40y, MSc.) “In question 3, replace the

pronoun ‘your.’ Because the user can speak

and make suggestions for other user profiles.

For example, I have a family member with vi-

sual impairment, and I can make suggestions

to improve their experience.”

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

456

5.7 Miscellaneous Suggestions

This category grouped suggestions that did not fit in

the previous categories. Some are aimed at the ini-

tial instructions for applying the questionnaire, such

as instructing the user to contact the researcher if they

have any questions (see P3’s comment) or even giving

users time to ask questions about the questionnaire

before starting to answer it. (see P7’s comment).

P3 (31-40y, phD.) “An instruction to contact

the researcher in case of doubt could be inter-

esting.”

P7 (31-40y, MSc.) “One tip is to allow time

for users to ask you their questions.”

6 DISCUSSION AND RESULTS

PROCESSING

After classifying the experts’ feedback, the next step

was to process all this input, analyzing what was pos-

sible and feasible to apply in UUXE-ToH. All classi-

fied comments were exported to a spreadsheet to facil-

itate the process, and an additional column was used

to identify which sentence or question the comment

was related to. Then, for each sentence in UUXE-

ToH, the comments with perceptions, considerations,

and suggestions about that sentence were analyzed.

Thus, it was possible to evaluate the comments.

We considered whether we could keep/remove, cor-

rect, modify, or move the sentence in UUXE-ToH.

For each comment, we indicate in another column

whether it was entirely, partially accepted, or rejected

and the respective action taken based on the evalua-

tion of the comment. For example, sentence 20 pre-

sented 14 comments in different categories (Consider-

ations, Perception of Similarity, Discard Suggestion,

and Miscellaneous Suggestions). Analyzing all the

comments together, it was decided to eliminate this

sentence and the respective construct (as just this sen-

tence represented it).

After analyzing the comments related to specific

sentences, the remaining comments were processed

by category. For example, all suggestions regarding

the Likert scale were analyzed. One suggested that

information on how the results should be analyzed in

the UUXE-ToH instruction manual be included. This

information was then added to the UUXE-ToH in-

struction manual. Below, we list some of the main

decisions made based on qualitative analysis of expert

feedback.

6.1 Removal Constructs

The Overall Usability construct, represented by sen-

tence 20 only, was removed. The experts considered

that Overall Usability could be inferred through other

constructs related to the usability criterion, such as

Effectiveness, Efficiency, and Learnability. Further-

more, the writing of sentence 20 would have been

very close to the points evaluated by sentences 9, 10,

and 13. Similarly, the General UX construct was re-

moved, represented solely by sentence 52 (I liked us-

ing the solution).

6.2 Adding a New Construct, Comfort

Experts suggested the creation of a new construct

called Comfort. This construct was created by com-

bining sentences 7, 8, and 54. The first two refer to

the absence of physical and mental fatigue, respec-

tively, and were previously allocated to the efficiency

construct, considering human effort as user resources

spent to achieve the goals. Sentence 54 explains the

absence of discomfort with the equipment necessary

to use the solution. This sentence represented the

physical component of the Satisfaction construct, a

result of the physical experience of using the solution.

Combining the three sentences into a single construct

highlights an essential aspect of solutions involving

user movement and wearable devices.

Comfort is related to ensuring that the user works

less but obtains a satisfactory or even maximized re-

sult. Whether from a physical or mental point of view,

the solution must reduce the effort required to achieve

the user’s objective. Wearable devices must be er-

gonomic and not painful for the user.

6.3 Modifying Emotion’s Sentences

The sentences for the Emotions construct were re-

formulated. Instead of four sentences, the construct

now has five sentences representing the families of

primary (or universal) emotions most commonly ref-

erenced by researchers: Happiness, Disgust, Sadness,

Fear, and Anger. Thus, the sentences for this con-

struct sought to assess whether the user felt positive

emotions or did not feel negative emotions. Each sen-

tence presents the most common name for the primary

emotion or one that could be related to the use of

interactive solutions and, in parentheses, some other

gradations of the same emotion family. For example,

sentence 64 became: “I felt happy (content, joyful)

when using the holographic solution.” In contrast,

a new sentence was added: “I did not feel sadness

(disappointment, disillusion) when using the holo-

Usability and User Experience Questionnaire Evaluation and Evolution for Touchable Holography

457

graphic solution.” Disgust was presented in the sen-

tence “I did not feel aversion (repulsion) for the holo-

graphic solution”. With this reformulation, responses

in agreement with the sentences of the emotion con-

struct indicate that the end user had positive feelings

or the absence of negative feelings during the experi-

ence with the holographic solution.

6.4 Discarding and Adding Sentences

Some sentences from UUXE-ToH have been re-

moved. For example, in the Learnability construct,

sentences 9 and 10 were removed because we under-

stand, as pointed out by the experts, that sentence 13

already dealt with the ease of learning the gestures

necessary for the interaction. In the Immersion con-

struct, sentence 31 was removed because it was under-

stood that the solution’s suitability to different light-

ing levels in the environment would not be a task to be

evaluated by the end user. Sentence 41, for example,

was removed because we understand, according to ex-

perts’ considerations, that “modern” does not mean

good. Furthermore, being modern does not neces-

sarily provide relevant information. Some sentences

were also removed because they were very similar to

others that already addressed the topic, such as sen-

tence 49, which was very similar to sentence 21. In

total, 14 sentences were removed from UUXE-ToH.

On the other hand, experts also suggested adding

new sentences to the constructs. In Memorability, a

new sentence was added to check whether the user

finds it easy to remember the sequence of steps to use

the solution and perform the main operations. In the

Immersion construct, a sentence was added to verify

the absence of problems with passing through a holo-

gram during the interaction (“I did not pass through a

hologram I wanted to interact with”). In Motivation,

a new sentence was added to check user engagement

when not noticing time passing during use. New sen-

tences were also added to the Satisfaction and Emo-

tions constructs.

6.5 Rewriting Sentences

UUXE-ToH sentences were revised based on expert

feedback, including simple adjustments like standard-

izing terms for common concepts. For example, sen-

tence six was modified from “This solution increases

my productivity when performing this type of task”

to “This holographic solution increases my produc-

tivity when performing this type of activity.” Other

sentences were changed to make the end user’s under-

standing easier, such as changing some words and/or

adding explanatory phrases. For example, sentence

23 of the immersion construct replaced the words

“quickly updated” with “in real-time,” giving the user

a better parameter to understand the sentence, which

also gained an additional phrase to explain the defini-

tion of a mixed environment.

6.6 Changes in Open Questions

The first open question underwent important changes.

Firstly, the options for marking, positive or negative,

were replaced by a 7-point semantic differential scale,

with the paired terms negative-positive so that the user

could indicate their experience in general terms. This

scale can be used to analyze the correlation between

the constructs in the objective part of the question-

naire and the general experience. Furthermore, in-

stead of just one open field to report the experience,

two fields were provided: one to describe the positive

experience and another to the negative experience.

A new question was added, resulting from con-

verting sentence 38 into an open question. Thus,

instead of just the user indicating whether the holo-

graphic solution is better than other solutions for the

same activity, it allows the evaluator to understand in

what sense the solution was considered (or not) bet-

ter than another for the user. This type of feedback is

much more enriching because it brings insights into

understanding what the user values in solutions for

that type of activity.

6.7 Grouping and Labeling

Although we believe that users should not know

which aspects make up Usability and UX or what they

are called, we understand that grouping the sentences

and labeling these groups can make it easier to under-

stand and complete the questionnaire. This can help

the user to differentiate sentences that may seem the

same at first, such as sentences 1 (Effectiveness) and

5 (Efficiency). Grouping also provides spacing (neg-

ative space) between sequences of sentences, which

is vital in layout, bringing less confusion and helping

the user focus on one group of sentences at a time.

7 UUXE-ToH v2

By compiling all the experts’ feedback, the new ver-

sion of the questionnaire (UUXE-ToH v2) now has

the following structure. The introduction now fea-

tures a glossary defining ”holographic solution” and

”hologram.” The initial evaluation section, ”Evalua-

tion by Aspect,” encompasses 60 sentences catego-

rized under Usability and UX dimensions. (Figure 3).

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

458

Figure 3: Part of UUXE-ToH v2.

The sentences continued to be evaluated using the 7-

point Likert scale. However, the answer option IDK

was removed. Some sentences that could be removed

by the applicator depending on the context or condi-

tion of the holographic solution were identified and

labeled as optional.

The second part of the assessment was identified

by ”Global Feedback” and now has a total of six ques-

tions, the first being a question with a semantic dif-

ferential scale (negative-positive) of seven levels and

five open questions, with space for the user to de-

scribe your experience, perceptions, and suggestions.

The second version of UUXE-ToH can be obtained at

https://figshare.com/s/229ae223135d66e79ad3.

8 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study marks a significant step in

developing an assessment questionnaire for touch-

able holography, with the UUXE-ToH questionnaire

emerging as a promising instrument after content and

face validation by experts. The constructive feedback

from experts was pivotal in refining and enhancing

the questionnaire. Qualitative analysis of the content

provided in interviews and forms gave us a compre-

hensive understanding of correcting and improving

the questionnaire. We learned important lessons, es-

pecially concerning the writing of sentences, always

seeking to maintain clarity and words that best reach

users’ understanding, including standardizing key ter-

minology to avoid doubts or different interpretations

between sentences. We also credit the reorganization

of some sentences into a new construct (Comfort),

and the modification of sentences in the Emotions

construct to the feedback received by the experts.

8.1 Limitations

While providing valuable insights into the content

and face validation of the assessment questionnaire

for touchable holography, this study faces limitations

that warrant acknowledgment. The modest sample

size raises concerns about generalizability, and the

opinions of experts, though insightful, might repre-

sent only a partial perspective. Additionally, the par-

ticipant pool, which comprises leaders of Brazilian

research groups, introduces potential regional bias.

Diverse expertise and experience levels among par-

ticipants could introduce variability in assessments,

with some experts lacking direct exposure to THS

technology, potentially restricting evaluations to the-

oretical knowledge or analogies with similar applica-

tions. When interpreting findings and assessing the

questionnaire’s applicability in specific contexts, re-

searchers should consider these limitations, including

sample size, geographic focus, and varied participant

knowledge levels. Expanding the participant pool and

conducting cross-cultural validations could enhance

the questionnaire’s robustness and broaden its overall

validity.

8.2 Future Works

For future work, the evolved UUXE-ToH question-

naire, now validated for content and face by experts,

will be employed in practical experiments involv-

ing THS. One study will aim to assess the question-

Usability and User Experience Questionnaire Evaluation and Evolution for Touchable Holography

459

naire’s reliability and validity through internal consis-

tency verification and factor analysis. Following this,

UUXE-ToH will evaluate the user experience across

THS solutions with varying technical qualities, inves-

tigating how constructs’ outcomes may reflect device

variations. Additionally, the questionnaire will be

tested in a scenario where potential users assess its ac-

ceptance. These studies will allow a practical applica-

tion of the UUXE-ToH in diverse contexts, contribut-

ing to a deeper understanding of user interactions in

touchable holography and offering insights into the

acceptance and effectiveness of THS across different

technical landscapes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the funding and support of the Coordina-

tion for the Improvement of Higher Education Per-

sonnel (CAPES)—Program of Academic Excellence

(PROEX).

REFERENCES

Aigner, R., Wigdor, D., Benko, H., Haller, M., Lindbauer,

D., Ion, A., Zhao, S., and Koh, J. T. K. V. (2012). Un-

derstanding Mid-Air Hand Gestures: A Study of Hu-

man Preferences in Usage of Gesture Types for HCI.

Technical Report MSR-TR-2012-111, Microsoft Re-

search.

Berkman, M. I. and Akan, E. (2019). Presence and Immer-

sion in Virtual Reality. In Lee, N., editor, Encyclo-

pedia of Computer Graphics and Games, pages 1–10.

Springer International Publishing, Cham.

Bevan, N., Carter, J., and Harker, S. (2015). ISO 9241-

11 Revised: What Have We Learnt About Usability

Since 1998? In Kurosu, M., editor, Human-Computer

Interaction: Design and Evaluation, Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, pages 143–151, Cham. Springer

International Publishing.

Bolarinwa, O. (2015). Principles and methods of validity

and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social

and health science researches. Nigerian Postgraduate

Medical Journal, 22(4):195.

Brooke, J. (1996). SUS: A ’Quick and Dirty’ Usability

Scale. In Usability Evaluation In Industry, pages 207–

212. CRC Press, London, 1st edition.

Campos, T. P. d., Damasceno, E. F., and Valentim, N. M. C.

(2023). Usability and User Experience Evaluation of

Touchable Holographic solutions: A Systematic Map-

ping Study. In IHC ’23: Proceedings of the 22st

Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, IHC ’23, pages 1–13, Maceio, Brazil.

ACM.

Corbin, J. and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of Qualitative

Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing

Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications, London, UK.

Costa, F. J. D. (2021). Mensuracao E Desenvolvimento De

Escalas. Ci

ˆ

encia Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, 1ª edic¸

˜

ao

edition.

DeVellis, R. F. and Thorpe, C. T. (2022). Scale develop-

ment: theory and applications. SAGE Publications,

Inc, Thousand Oaks, California, 5th edition.

Finstad, K. (2010). Response Interpolation and Scale Sen-

sitivity: Evidence Against 5-Point Scales - JUX. JUS

- Journal of Usability Studies, 5(3):104–110.

Gao, M., Kortum, P., and Oswald, F. (2018). Psychome-

tric Evaluation of the USE (Usefulness, Satisfaction,

and Ease of use) Questionnaire for Reliability and Va-

lidity. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Er-

gonomics Society Annual Meeting, 62(1):1414–1418.

Hassenzahl, M. (2011). User Experience and Experience

Design. In The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer In-

teraction. Interaction Design Fundation, online, 2nd

edition.

ISO (2018). ISO 9241-11:2018 Ergonomics of human-

system interaction — Part 11: Usability: Definitions

and concepts. Technical report, International Organi-

zation for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Kennedy, R. S., Lane, N. E., Berbaum, K. S., and Lilien-

thal, M. G. (1993). Simulator Sickness Questionnaire:

An Enhanced Method for Quantifying Simulator Sick-

ness. The International Journal of Aviation Psychol-

ogy, 3(3):203–220.

Kervegant, C., Raymond, F., Graeff, D., and Castet, J.

(2017). Touch hologram in mid-air. In ACM SIG-

GRAPH 2017 Emerging Technologies, SIGGRAPH

’17, pages 1–2, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Koller, I., Levenson, M. R., and Gl

¨

uck, J. (2017). What Do

You Think You Are Measuring? A Mixed-Methods

Procedure for Assessing the Content Validity of Test

Items and Theory-Based Scaling. Frontiers in Psy-

chology, 8.

Laugwitz, B., Held, T., and Schrepp, M. (2008). Construc-

tion and Evaluation of a User Experience Question-

naire. In Holzinger, A., editor, HCI and Usability for

Education and Work, Lecture Notes in Computer Sci-

ence, pages 63–76, Graz, Austria. Springer.

Lund, A. M. (2001). Measuring usability with the USE

questionnaire. Usability interface, 8(2):3–6.

Marchionini, G. (2006). Exploratory search: from find-

ing to understanding. Communications of the ACM,

49(4):41–46.

Microsoft Inc (2022). What is a hologram? - Mixed Reality.

Nielsen, J. (2012). Usability 101: Introduction to Usability.

Shull, F., Carver, J., and Travassos, G. H. (2001). An

empirical methodology for introducing software pro-

cesses. ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes,

26(5):288–296.

Skarbez, R., Brooks, Jr., F. P., and Whitton, M. C. (2017).

A Survey of Presence and Related Concepts. ACM

Computing Surveys, 50(6):96:1–96:39.

Skarbez, R., Smith, M., and Whitton, M. C. (2021). Revisit-

ing Milgram and Kishino’s Reality-Virtuality Contin-

uum. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 2:647997.

Slater, M. (2018). Immersion and the illusion of presence in

virtual reality. British Journal of Psychology (London,

England: 1953), 109(3):431–433.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

460