A Survey on Storytelling Techniques for Heritage on Nazi Persecution

Niek Meffert

1

, Camilla Vang Østergaard

1

, Stefan J

¨

anicke

1 a

, Richard Khulusi

2 b

, Esther Rachow

3

,

and Nicklas Sindlev Andersen

1 c

1

Centre for Visual Data Science, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

2

Bergen-Belsen Memorial, Lohheide, Germany

3

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

Keywords:

Visual Storytelling, Interactive Media, Cultural Heritage, Nazi Persecution, Digital Humanities.

Abstract:

This paper explores Visual Storytelling (VS) as a means of conveying historical narratives, with a particu-

lar focus on Heritage related to Nazi Persecution (HNP). We refine and augment existing design spaces in

information visualization to broaden the scope and emphasize rich media elements while orienting our re-

fined design space towards VS for HNP. We analyze dimensions central for storytelling focusing on cultural

heritage, while digging deeper into aspects relevant for HNP like specific types of text (testimonies, diaries,

official documents) and person types (victims, survivors, persecutors). The key contribution of our study is the

development of a design space uniquely tailored to HNP, which highlights critical elements and trends from

existing storytelling projects, and comprehensively examines the unique challenges and opportunities within

VS for HNP. Furthermore, we discuss future directions, enriching the evolving domain of VS by equipping

heritage professionals and researchers with practical strategies to craft compelling narratives that aim to en-

gage contemporary audiences and to preserve the historical accuracy and ethical integrity of HNP.

1 INTRODUCTION

Firsthand witnesses of important historical events

fade with time, and the urgency to capture their tes-

timonies and experiences for future generations thus

becomes increasingly important. In this context, Cul-

tural Heritage (CH) institutions are faced with the task

of not only preserving the collective memory of sig-

nificant events but also conveying them in a manner

that resonates with contemporary audiences. As the

media landscape undergoes rapid transformations, in-

novative strategies become vital in ensuring these pre-

served memories remain accessible and relevant to a

broad audience.

Visual storytelling (VS) embodies a storytelling

approach that combines narrative with visual design.

It is a promising avenue that has demonstrated the

potential to bring diverse historical narratives to life.

Drawing upon current research and development in

this area, we survey storytelling, focusing specifically

on VS for CH sites related to the Heritage of Nazi Per-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9353-5212

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9964-8090

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6926-1397

secution (HNP). We build upon prior work by Kus-

nick et al. (2021), which assemble a robust design

space of visualization-based storytelling (VBS) de-

sign choices specifically assembled for the digital hu-

manities and CH domain. Our goal is to adapt and

enhance this framework, placing a greater focus on

incorporating rich media elements to orient it towards

CH sites and tailor it around the narration of histori-

cal events, like the Holocaust. We thus aim to create a

more expansive and effective design space for VS for

HNP. In adapting the design space, we modify and

discard specific dimensions and incorporate and in-

terweave new categories and sub-categories. The ad-

dition of new categories or removal of existing ones

is based on the analysis of a refined list of storytelling

instances and related works focusing on storytelling.

Ultimately, this work allows us to identify trends, pos-

sible gaps, and missed opportunities in storytelling-

focused and technology-driven projects in various ar-

eas of historical remembrance and digital heritage.

Meffert, N., Østergaard, C., Jänicke, S., Khulusi, R., Rachow, E. and Andersen, N.

A Survey on Storytelling Techniques for Heritage on Nazi Persecution.

DOI: 10.5220/0012573200003660

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 19th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2024) - Volume 1: GRAPP, HUCAPP

and IVAPP, pages 603-615

ISBN: 978-989-758-679-8; ISSN: 2184-4321

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

603

2 RELATED WORK

In terms of related work, we primarily summarize

prior work that aims to identify central and vital build-

ing blocks for constructing narrative stories. Segel

and Heer (2010) established the foundational work

on data-driven and narrative storytelling. They intro-

duced key practices primarily centered on the jour-

nalistic reinterpretation of data into compelling vi-

sual narratives. Segel and Heer categorized these nar-

ratives based on three primary criteria: genre (the

main visualization technique utilized), VS tactics (in-

volving visual structuring, highlighting, and guidance

through transitions), and narrative structure strategies

(encompassing ordering, interactivity, and messag-

ing).

Subsequent research has expanded upon Segel and

Heer’s foundation. For instance, Tong et al. (2018)

conducted a comprehensive review of storytelling in

data visualization, analyzing various VS elements in

scientific publications. Their examination addressed

questions such as” Who?” (related to authoring tools

and user engagement), ”How?” (involving narratives

and transitions), and ”Why?” (concerning memorabil-

ity and interpretation). They also extended Segel and

Heer’s classification by introducing a second layer

of categorization, which examines the sequence of

events (linear, user-directed path, parallel, and ran-

dom). In the realm of newer web-based and data-

driven stories, Stolper et al. (2016) expanded upon

Segel and Heer’s foundation. They introduced addi-

tional genres (e.g., timelines), narrative structure tac-

tics (e.g., interactive brushing and linking), messag-

ing (e.g., audio), and VS tactics (e.g., linking sep-

arated story elements). Additionally, Gershon and

Page (2001) examined the role of storytelling in in-

formation visualization, addressing topics that over-

lap with those explored by Stolper et al. (2016).

Some researchers have acknowledged Segel and

Heer’s work while developing their own frameworks.

For instance, McKenna et al. (2017) identified seven

factors contributing to the flow of visual narratives.

Latif et al. (2021) examined the spatial arrangement

and interactive linking of visualization and text, em-

phasizing its impact on reception, engagement, com-

prehension, and recall. They explored various meth-

ods to integrate visualizations into the narration seam-

lessly.

Zhao and Elmqvist (2023) introduced their unique

design space and analysis framework. Their frame-

work includes dimensions such as audience cardinal-

ity (describing the number of storytellers and recipi-

ents), space and time (impacting the delivery and stor-

age mechanism for data-driven storytelling), media

components (defining the composition of data-driven

storytelling), data components (conveying data from

the storyteller to the viewer), and viewing sequence

(describing the level of interactivity associated with a

storytelling artifact). The framework aims to provide

practical guidance for creating stories.

In a related context of narrative storytelling, Kim

et al. (2018) introduced the concept of story curves.

They applied this visualization technique to ana-

lyze narrated fiction’s (non-)linearity, particularly in

movies, drawing inspiration from Genette’s nonlinear

narrative patterns (Genette, 1983). Kim et al. (2018)

extended classical patterns with new ones, exploring

how historical events are ordered in narration.

Additionally, Roth (2021) contributed to carto-

graphic design by offering three perspectives on VS.

These include foundational plot patterns, which fol-

low the three-act structure and incorporate basic plot

patterns. While not directly connected to Segel and

Heer’s work, these perspectives enrich the overall

landscape of research in narrative storytelling.

From the perspective of emergent and computa-

tional digital storytelling, Trichopoulos et al. (2023)

also touches upon the fundamental elements of story-

telling that we have previously mentioned. Notably,

their research focuses on contemporary works encom-

passing authoring tools, systems, applications, meth-

ods, frameworks, and case studies. They categorize

these works based on aspects like scope (e.g., edu-

cation, CH, games), media (including tangible inter-

active digital narrative, gesture recognition, embod-

ied digital storytelling, VR/AR, video, and anima-

tion), and interaction methods (e.g., cards, paper ob-

jects, embodied replicas, special objects, hand ges-

tures). This perspective provides insights into how

technology is reshaping storytelling, with computers

and algorithms increasingly integrated into the narra-

tive creation and presentation processes.

Finally, the survey by Kusnick et al. (2021) fo-

cuses on VBS in digital humanities and CH. Their

paper builds directly upon the concepts and various

aspects introduced in the earlier mentioned work and

surveys prototypical storytelling instances relying on

visualizations. Based on the prior work and the anal-

ysis of prototypical VBS instances, a comprehensive

and robust design space is assembled that defines the

vital building blocks for creating VBS narratives in

the digital humanities and CH domain.

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

604

3 SURVEY SCOPE &

METHODOLOGY

On the topic of VS, a multitude of approaches and

projects exist. However, this survey narrows its focus

to those specifically related to CH sites and with a

strong emphasis on those within an HNP context.

3.1 Search Procedure

To obtain a representative set of VS instances, we

took a crowd-sourced approach, resulting in 174 in-

stances of different VS projects. These were collected

and provided by members affiliated with the MEMO-

RISE project

1

. These members comprise profession-

als operating in the heritage sector.

To obtain a small but varied sample of exemplary

storytelling instances from the much larger pool of

crowd-sourced instances, we applied the following

exclusion criteria to filter out storytelling instances:

Restricted Access. We eliminated storytelling in-

stances if they were not easily accessible e.g. due

to broken links or content hidden behind paywalls.

Location-Dependent Usability. Instances were also

excluded if their use was limited to specific geo-

graphical locations.

Concept Demonstrations. Moreover, we excluded

instances that were in the early stages of devel-

opment or served merely as demonstrative proofs

of concept without a functional, user-ready imple-

mentation or product.

Simple Storytelling Instances. Instances were ex-

cluded if they lacked a clear narrative structure or

used only a limited range of VS means (i.e. if only

a few design dimensions of Table 1 were used for

conveying the narrative).

By applying the exclusion criteria, we ended up

with a final sample of 20 VS instances. As indicated

by the last exclusion criterion, the pool of instances

was brought down through a preliminary analysis ac-

cording to the design space put forth by Kusnick et al.

(2021). In this context, we mention that at least two of

the authors of this paper were involved in the exclu-

sion and subsequent analysis of storytelling instances,

determining which ones to exclude and which to in-

clude for further in-depth analysis. This collaborative

approach was also applied to the in-depth analysis of

specific storytelling instances, ensuring a more reli-

able evaluation of the instances.

Lastly, to give an idea of the nature of instances we

later explore in detail, we specifically examine four

1

Dissemination website: https://memorise.sdu.dk/

Figure 1: Yad Vashem’s Online Database (Yad Vashem,

2023): A database that provides information about the

movement of Jews from Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia,

Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg,

and the Netherlands between 1939 and 1945.

exemplary instances, each illustrating a distinct ap-

proach to VS in the context of HNP. These examples,

chosen for their diversity in implementation, range

from comprehensive, multi-modal presentations to

more focused, singular narrative forms.

Yad Vashem’s Online Database (Yad Vashem,

2023). This comprehensive database, created by the

International Institute for Holocaust Research, pro-

vides information on the movement of Jewish popula-

tions across Europe from 1939 to 1945. It utilizes an

array of visual elements including topography, info-

graphics, animations, timelines, images, and text (see

Figure 1). The database offers a macro-view of exten-

sive data, allowing users to also delve into specific lo-

cations and individual stories. It starts with a brief lin-

ear exploration, outlining the project’s scope, and then

transitions to an interactive and exploratory user expe-

rience. The design encourages users to engage more

deeply with the content, blending structured guidance

with opportunities for free exploration.

Catastrophe Questioning Eichmann’s numbers

(Ba

´

nkowska et al., 2023). Developed by the edu-

cational site House of the Wannsee Conference, this

application focuses on the statistics of Adolf Eich-

mann’s “final solution”. Shown in Figure 2, it effec-

tively uses text, imagery, sound, video, scrollytelling,

infographics, interactive maps, and timelines. The

narrative begins linearly, introducing background in-

formation, and then shifts to an interactive map for

exploring in-depth stories of the 11 million victims.

The site’s use of varied VS creates a personal and

immersive experience, connecting users emotionally

with the data.

Ravensbr

¨

uck Digital Tour (Europa-Universit

¨

at Vi-

adrina, 2023). Showcased in Figure 3, this web

A Survey on Storytelling Techniques for Heritage on Nazi Persecution

605

Figure 2: Catastrophe Questioning Eichmann’s numbers

(Ba

´

nkowska et al., 2023): A website blending topogra-

phy, infographics, animations, timelines, images, and text

to present an extensive HNP dataset, offering a macro

overview and enabling users to explore specific locations

and individual stories.

Figure 3: Ravensbr

¨

uck Digital Tour (Europa-Universit

¨

at Vi-

adrina, 2023): An interactive web app providing a guided

digital tour of the Ravensbr

¨

uck women’s concentration

camp. It employs narrative audio and text, focusing on a

specific historical site, and offers a linear, informative ex-

ploration of the camp’s history.

app offers a digital exploration of the Ravensbr

¨

uck

women’s concentration camp. It starts with a

narrative-driven video tour of the site as it currently

stands, supplemented by textual information. The app

adopts a minimalist approach to VS, focusing on a

specific and narrow subject, thus providing a linear

and informative journey through this historical site.

The Commander’s House at Camp Westerbork

(Campscapes Westerbork, 2022). Showcased in

Figure 4, the virtual tour begins with a linear intro-

duction featuring video and text about the site’s his-

tory. Users are then guided to a 3D rendition of the

commander’s house, which they can explore freely.

Interactive text pop-ups appear at points of interest.

The site blends various VS elements—video, audio,

text, imagery, and virtual tours—to focus on a sin-

gular historical location. The absence of a guiding

user interface offers a slower-paced, immersive expe-

rience, though at the cost of a more direct informa-

tional delivery.

Figure 4: The Commander’s House at Camp Westerbork

(Campscapes Westerbork, 2022): A detailed virtual expe-

rience by Camp Westerbork exploring the Commander’s

house. The tour combines video, audio, text, and 3D vi-

suals, offering a self-guided exploration with interactive el-

ements to immerse users in the historical context of the lo-

cation.

3.2 Methodology

After defining the applicable sources of projects, the

analytical methodology has to be addressed. These

include design trends and exploring potential avenues

within VS for CH sites focusing on HNP.

Refinement of the Design Space. The preliminary

assessment of the 20 exemplary VS instances

prompted the refinement of the existing design

space proposed by Kusnick et al. (2021). This

led to a modified and more focused design space

appropriate for HNP. In the context of describing

the design dimensions that were kept from the

original design space, we describe relevant VS

instances that incorporate the building blocks

identified by the design dimensions. We then

give the full tabular analysis of the examples

according to the design dimensions that were kept

(see Table 1).

Augmentation of the Design Space. After analyz-

ing VS instances with the refined design space,

new aspects emerge, leading to its augmentation.

This augmentation includes additional story-

telling elements specific to HNP. It broadens

the framework, offering a more comprehensive

guide for creating and evaluating visual stories

in the context of CH. This expanded design

space ensures a nuanced approach, addressing

the unique sensitivities and specifics of HNP

storytelling.

4 REFINED DESIGN SPACE

In conveying narratives related to HNP, specific di-

mensions of the VBS design space by Kusnick et al.

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

606

(2021) stand out for their potential to create impactful

storytelling experiences.

Entity-Orientation. The entity-orientation dimen-

sion identifies specific entities like objects, persons,

sets, events, and places around which stories re-

volve. For example, the Commander’s house tour by

Camp Westerbork (Campscapes Westerbork, 2022)

highlights a specific place, while the Danish Jews in

Theresienstadt webpage (Stræde and Hansen, 2018)

brings to life stories centered around individuals.

Story Complexity. The complexity of HNP stories,

in terms of entity numbers and temporal scope, is piv-

otal for conveying narratives effectively. Through a

preliminary assessment of storytelling instances, we

saw a preference for complex, synchronic story struc-

tures combined with simpler, diachronic elements, al-

lowing narratives like those on the Topography of Vi-

olence site (JMB, 2023) to present numerous entities

in an accessible manner.

Story Schemata. The structure of stories within the

HNP context reveals various story schemata that or-

ganize internal narrative architecture. These range

from actor, object, and location-based biographies to

a spectrum of set biographies. In HNP data, per-

sonal biographies are common, often combined with

sequences or bundles of biographies, as seen in the

webpage about the Wansee Conference (Chenchanna

and Gogelein, 2022), which allows exploration of dif-

ferent rooms and stories. This approach falls under

set biographies, enabling users to delve into diverse

stories within a single framework. Such schemata en-

able the bundling of individual and collective histories

into a larger narrative, providing a more comprehen-

sive view of history and heritage.

Media Types. Integrating diverse media types: au-

dio, text, images, film, and visualizations—forms the

core of visual storytelling. Blending these media

types enriches the narrative, making it more immer-

sive and impactful. Audio, for instance, plays a mul-

tifaceted role, from setting the atmosphere with back-

ground music (Ba

´

nkowska et al., 2023) to enhanc-

ing accessibility in terms of speech narration (Deinert

and Maier, 2020). An example is the Instagram story

about Gerrit Jongsma (O’Neill and Jongsma, 2021),

where a voiceover effectively carries the narrative.

Visualization Types. Various visualization types,

such as timelines, maps, graphs, and set-based vi-

sualizations, offer distinct ways to represent histori-

cal context and relationships. Timelines and maps,

like those in the Stolpersteine webpage (WDR, 2023),

provide a clear chronological and geographical per-

spective, while set-based visualizations categorize en-

tities. Graphs and charts, though less common, can

forge empathetic connections between data and indi-

vidual stories when used thoughtfully, as seen in the

Questioning Eichmann webpage (Ba

´

nkowska et al.,

2023).

Story Thread & Media-Text Linking. The story

thread and media-text linking dimension ensure a co-

hesive narrative flow in visual stories. The primary

threading method is language, either as written text or

spoken narration, which binds together various media

elements. Effective techniques include in-text refer-

ences to media content and coordinated scrolling, en-

hancing the interplay between text and media as seen

in the Liberation of Dachau site (Deinert and Maier,

2020).

Story Composition. We consider story composi-

tion options in HNP narratives to range from single

narrative pathways through various media arrange-

ments to multiple pathways offering diverse perspec-

tives. This dimension influences how viewers engage

with the content, as seen in the Topography of Vi-

olence site (JMB, 2023), where a mix of narrative

and exploration options allows viewers to choose their

path, thereby enhancing interaction and engagement.

Uncertainty. In the context of HNP narratives, bal-

ancing factual content with elements that address un-

certainties is crucial (Windhager et al., 2019; Liem

et al., 2023). This aspect is key to maintaining histor-

ical accuracy and ensuring respectful representation.

We identify two ways of displaying uncertainty in vi-

sual stories, namely quantified uncertainty whenever

it is possible to quantify the uncertainty in terms of

numbers thus being able to display and visualize the

uncertainty. Interpretet uncertainty is when the lack

of data has been interpreted to some extent (typically

by a domain expert) and a visual indication (e.g. a

deliberate gap or a question mark) can be incorpo-

rated into the story. A good example of Quantified un-

certainty is the Topography of Violence website JMB

(The Jewish Museum Berlin) (2023). The cite creates

visualizations of the acts of violence against the Jew-

ish population and combines known knowledge with

unknown elements to tell the story to the viewer.

An intriguing example of blending factuality with

creative elements is found in the use of a playable di-

ary on the ’Traces of Paper’ website (Wehnen Memo-

rial, 2021). This diary, rooted in real-life events and

A Survey on Storytelling Techniques for Heritage on Nazi Persecution

607

personal accounts, incorporates fictitious elements to

enhance viewer engagement through gamification.

Discarded Design Dimensions. Specific dimen-

sions of the original VBS design space were not em-

phasized for narratives related to HNP due to several

reasons. For instance, while plot patterns and struc-

tures provide a framework for storytelling, we argue

that the actual events and their accurate portrayal take

precedence in historical narratives like HNP. Using

classic plot structures like genesis, emergence, and

metamorphosis plots might not always be feasible or

appropriate, given the nature of events related to HNP.

Similarly, story arcs and hooks, crucial in fiction

and other storytelling forms, are approached differ-

ently in the context of HNP. The focus here is on pre-

senting historical facts and narratives in an informa-

tive and respectful manner rather than creating dra-

matic arcs or engaging hooks that could potentially

trivialize the subject matter.

While an important narrative technique, the lin-

earity or non-linearity of the story is less of a de-

liberate choice and more a reflection of how histor-

ical events unfolded. In HNP, a linear approach often

naturally arises from the chronological sequence of

events, although non-linear storytelling can be com-

pelling when used appropriately. On the other hand,

it might introduce a more complex story structure.

Lastly, gamification in storytelling about sensitive

topics like HNP can be controversial. It is crucial to

handle such topics with respect and sensitivity, and

gamification elements might risk undermining the se-

riousness of the subject matter. Similarly, due to these

concerns, we discarded the categories relating to in-

corporating fictitious elements.

Finally, due to our exclusion criteria focused

on location-dependent usability, as detailed in Sec-

tion 3.1, we have omitted the design dimension of tar-

get devices from our consideration. This decision is

based on the understanding that storytelling instances

primarily designed for mobile devices are likely to be

filtered out during our selection process. Mobile de-

vices are inherently suited for applications like on-

site augmented reality (AR) or location-dependent in-

tegration, which relate to how a visual story unfolds

at a specific site.

5 ANALYSIS

During the analysis, the dominant entity types in

the VS instances were persons, followed by places,

events, objects, and settings. This indicates a fo-

cus on individuals, especially their personal stories,

in presenting narratives related to HNP. Diachronic

(chronological) stories were more prevalent than syn-

chronic (non-chronological), with a preference for

simple to medium-complex story structures. This ob-

servation is consistent with the goal of reaching a

broad audience.

Text was found to be the most common media

type, often supported by secondary types such as im-

ages, video, or interactive media. Information is often

presented as freely explorable, allowing viewers to

engage at their own pace. To keep users interested, a

clear reason for investment, personal interest, engage-

ment through interactivity, or a call to action is essen-

tial. The analysis suggests a correlation between the

variety of elements in the design space and the size of

the data sets, highlighting the need for different pre-

sentation elements for different topics. The common

use of a combination of synchronous and diachronic

story complexity reflects a strategy to offer both sim-

plified information and more in-depth analysis for a

balanced user experience. Timelines and maps were

the most frequently used visualization types, reflect-

ing a preference for conveying temporal and spatial

information. The predominant narrative thread was

temporal succession, with text and speech as the ele-

ments that carried the story, emphasizing linear story-

telling with a temporal focus.

In terms of interactive implementations, anima-

tion, slideshow, and moving camera were used in sev-

eral examples, suggesting a preference for dynamic

elements. The tabular analysis also revealed that, in

some instances, there were multiple narrative paths

and mixed narrative and exploration, highlighting a

tendency to provide users with options for different

story experiences. The absence of the slideshow +

moving camera combination suggests a cautious ap-

proach to incorporating more advanced dynamic ele-

ments, potentially to ensure usability.

In summary, the analysis indicates a preference

for diachronic narratives, a focus on individual enti-

ties (especially persons), a reliance on textual infor-

mation supplemented by audio and visual elements,

and a desire for dynamic interactive features. In par-

ticular, there is a clear tendency to portray information

through a combination of simple synchronous and

more complex diachronic approaches or vice versa

to create a balanced experience for the end user, of-

fering either simplified information on many subjects

or more in-depth analysis of selected subjects. Story-

tellers aim to address a diverse audience with different

levels of interest and engagement.

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

608

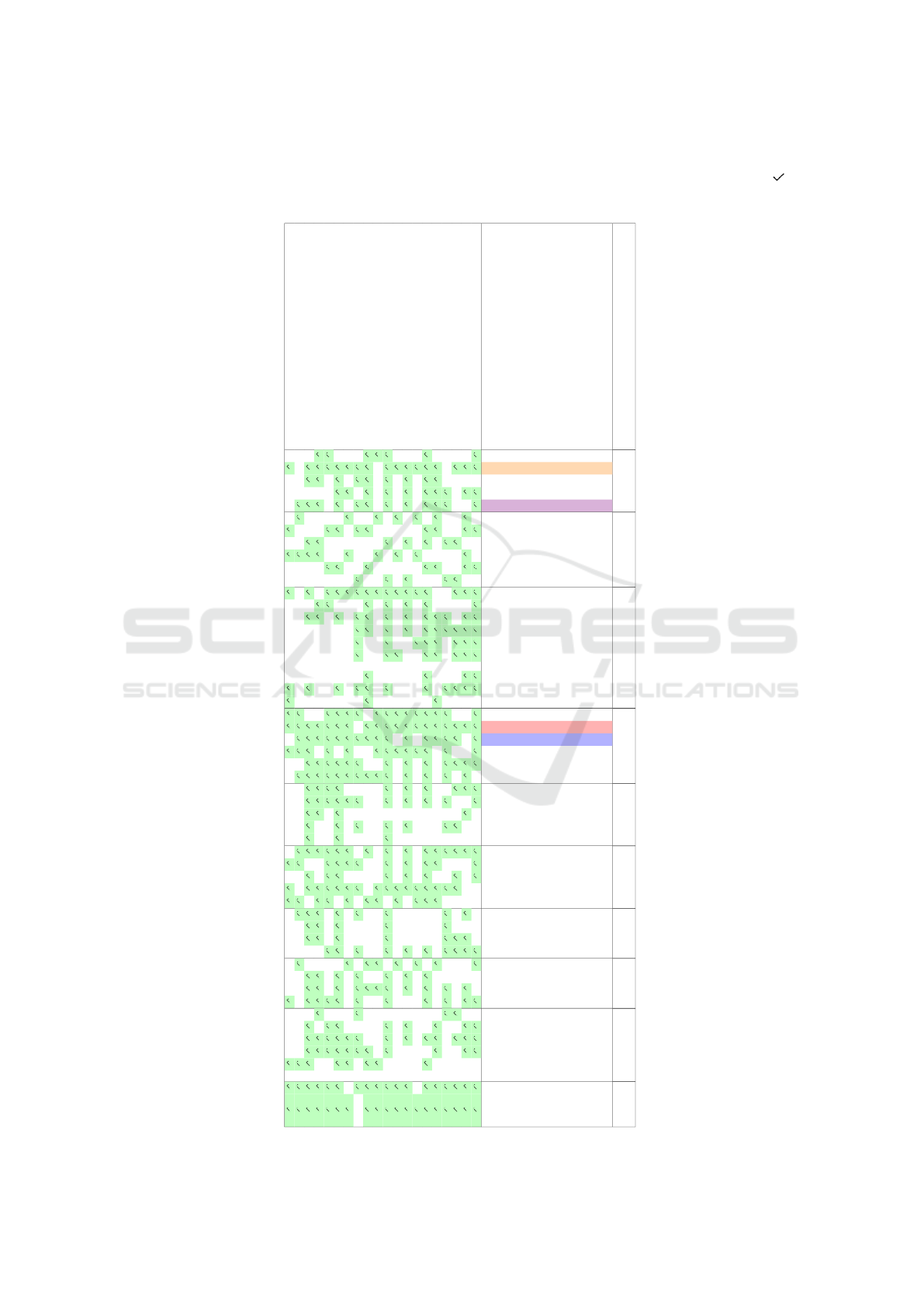

Table 1: The table provides a summary of the refined narrative storytelling design space and the analyzed storytelling in-

stances. Rows represent different storytelling instances, and columns show design dimensions. A checkmark icon ( ) in

a cell signals that the instance has the noted characteristic or feature. The colored categories (orange, purple, red, and blue)

indicate categories that have been elaborated on in Table 2.

Entity

Orientation Story Complexity Story Schemata Media Types Vis Types Story Thread

Media-Text

Linking

Story

Composition

Interactive

Implementation Uncertainty

Storytelling Instance (Name)

Objects

Persons

Sets

Events

Places

Synchronic: Simple

Synchronic: Medium

Synchronic: Complex

Diachronic: Simple

Diachronic: Medium

Diachronic: Complex

Actor Biography

Object Biography

Place Biography

Hybrid Biography

Biography Sequences

Biography Bundles

Inverted Trees

Trees

Larger Topic / Era

Larger Topic / Multi-era

Audio

Text

Images

Film

Visualizations

Interactive Media

Timeline

Map

Graph

Set

Chart

Text

Speech

Juxtaposition

Temporal Succession

Moving Camera

In-Text References

Visualization Legend

Annotation

Coordinated Scrolling

Single Narrative Pathway

Multiple Arrangements

Multiple Narrative Pathways

Mixed Narrative & Exploration

Annotated Chart

Scrollytelling

Animation

Slideshow

Moving Camera

Slideshow + Moving Camera

Quantified

Interpreted

L

¨

uneburg forced sterilization (Rudnick, 2022)

On This Day 1945 (BMDMF, 2021)

Der Anfang vom ende (JMB, 2013)

Danish jews in Theresienstadt (Stræde and Hansen, 2018)

Liberation of Dachau (Deinert and Maier, 2020)

The Wansee Conference (Chenchanna and Gogelein, 2022)

Eva Heyman’s Instagram story (Kochavi and Kochavi, 2019)

The Action T4 commemoration (RLEGL, 2022)

Instagram story about Gerrit Jongsma (O’Neill and Jongsma, 2021)

Keeping memories (Dive Project, 2023)

Lediz (LMUM, 2018)

Mahn und Gedenkst

¨

atte (art.vision, 2020)

Memory loops (Melian, 2010)

Traces of paper (Wehnen Memorial, 2021)

Questioning Eichmann (Ba

´

nkowska et al., 2023)

Stolen memory (Arolsen Archives, 2022)

Stolpersteine (WDR, 2023)

Topography of Violence (JMB, 2023)

The Commander’s House (Campscapes Westerbork, 2022)

Zeitzeugenportal (Rosenberger, 2018)

A Survey on Storytelling Techniques for Heritage on Nazi Persecution

609

Table 2: An augmentation of the refined storytelling design space in Table 1. The same storytelling instances are analyzed,

but now, according to a more fine-grained categorization. A checkmark icon ( ) in a cell indicates that the instance has the

noted characteristic/feature. The colored categories (orange, purple, red, and blue) correspond to categories in Table 2.

Person Types Place Types Text Types Image Types Accessibility

Storytelling Instance (Name)

Victim

Survivor

Persecutor

Current

Past

Testimony

Diary

Official Document

First Hand

Second Hand

Basic

Intermediate

Advanced

L

¨

uneburg forced sterilization (Rudnick, 2022)

On This Day 1945 (BMDMF, 2021)

Der Anfang vom ende (JMB, 2013)

Danish jews in Theresienstadt (Stræde and Hansen, 2018)

Liberation of Dachau (Deinert and Maier, 2020)

The Wansee Conference (Chenchanna and Gogelein, 2022)

Eva Heyman’s Instagram story (Kochavi and Kochavi, 2019)

The Action T4 commemoration (RLEGL, 2022)

Instagram story about Gerrit Jongsma (O’Neill and Jongsma, 2021)

Keeping memories (Dive Project, 2023)

Lediz (LMUM, 2018)

Mahn und Gedenkst

¨

atte (art.vision, 2020)

Memory loops (Melian, 2010)

Traces of paper (Wehnen Memorial, 2021)

Questioning Eichmann (Ba

´

nkowska et al., 2023)

Stolen memory (Arolsen Archives, 2022)

Stolpersteine (WDR, 2023)

Topography of Violence (JMB, 2023)

The Commander’s House (Campscapes Westerbork, 2022)

Zeitzeugenportal (Rosenberger, 2018)

6 AUGMENTED DESIGN SPACE

Through our analysis, we discerned recurring themes

extending beyond our refined design space. These

themes notably include the utilization of specific

types of source materials like testimonies, diaries, and

official documents. Our augmented design space ac-

knowledges the significance of source material, at-

tributing to it a greater weight than the general format

delineated in the design space analysis in Table 1.

We refined the design space further, focusing par-

ticularly on media types and entity orientation — ar-

eas we found crucial for CH sites with an HNP focus.

Within media types, such as images and text, and un-

der entity orientation, such as persons and places, we

made nuanced distinctions. Images were categorized

based on their compositional role: first-hand images

directly support the text, while second-hand images

set the atmosphere. For text, we focused on its ori-

gins, whether in testimonies, diaries, or official doc-

uments, and evaluated the elaborateness of accessi-

bility features, ranging from basic, intermediate, and

advanced.

Accessibility. In tailoring experiences for CH that

cater to diverse audiences across different age groups,

cultural backgrounds, and prior knowledge levels, ac-

cessibility becomes paramount. An insignificant part

of the global population faces some form of disability

limiting internet access (WHO, 2011). Our design so-

lution aims to include this demographic. We catego-

rized accessibility into three levels based on available

functions: Basic is just a single simple feature, such

as language switching. Intermediate offers 2-3 op-

tions, and more elaborate functions such as simplified

text or read-aloud features. Advanced provides +4 op-

tions, such as a dedicated accessibility toolbar provid-

ing alternative navigational aids, toggling of special

visual indicators, etc.

Image Types. We divided images into two subcat-

egories for the media types design dimension: First

Hand includes images that supplement textual con-

tent, such as portraits in descriptions or interviews, or

images depicting scenarios or locations mentioned in

the text. Second Hand includes images intended to

evoke specific moods or atmospheres, often achieved

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

610

through background imagery that complements the

textual narrative. Sites like the L

¨

uneburg forced ster-

ilization page (Rudnick, 2022), the Action T4 com-

memoration page (RLEGL, 2022), and Stolen Memo-

ries (Arolsen Archives, 2022) exemplify the effective

use of these image types, combining portraits, docu-

ment images, and video clips to enhance narratives.

Text Types. We categorized text into diaries, tes-

timonies, and official documents, recognizing their

prevalence and the need for careful visualization. It

is vital to convey personal memories and stories eth-

ically while acknowledging the subjectivity of di-

aries and testimonies and the potential dubiousness

of some official documents. ”On This Day 1945”

(BMDMF, 2021) illustrates this approach, using var-

ious text types to narrate concentration camp stories,

supported by relevant images. We need to be cau-

tious when visualizing quantitative data from subjec-

tive sources, as charts and graphs can be misleadingly

perceived as objective truths (Isberner et al., 2013).

Testimonies and diaries often include textual and vi-

sual elements, while official documents frequently

lack text transcripts, highlighting a potential accessi-

bility gap.

Person & Place Types. We further refined the en-

tity orientation dimension for persons and places. Per-

sons are categorized as victims, survivors, or perse-

cutors, as these groups are central in HNP narratives.

For instance, the Westerbork commander’s house tour

(Campscapes Westerbork, 2022) tells the story from

the persecutor’s perspective, while the Danish Jews

in Theresienstadt page (Stræde and Hansen, 2018)

and Eva Heyman’s Instagram story (Kochavi and

Kochavi, 2019) provide survivor and victim perspec-

tives, respectively. Places are classified as current or

past, acknowledging the transformation of geographi-

cal locations over time. The Liberation of Dachau site

(Deinert and Maier, 2020) effectively demonstrates

this concept by overlaying present-day images with

historical ones.

7 CHALLENGES &

OPPORTUNITIES

Despite being able to provide a comprehensive

overview of the new augmented design space in Sec-

tion 6, it is important to emphasize that there are still

various challenges that offer great potential and op-

portunities for future work. In this section, we dive

deeper into these opportunities and challenges.

Historical Accuracy & Integrity. Incorporating

data-driven elements into narratives about CH sites

poses a challenge in preserving historical accuracy

and integrity (Bradley, 2005; M

¨

uller, 2002; Man

ˇ

zuch,

2017). It is essential to stay true to sources, ensur-

ing that both tangible and intangible historical as-

sets, once digitized, genuinely mirror history instead

of unintentionally distorting it (Boyd Davis et al.,

2021; M

¨

uller, 2002; Koller et al., 2009; Brown and

Waterhouse-Watson, 2014). There is also a risk of

oversimplification when translating these assets into

data or visualizations (Santana Quintero et al., 2020;

Koller et al., 2009). Many historical records offer

data that are either ambiguous or incomplete (Van-

cisin et al., 2023), either because the records only

have a narrow focus or parts of them have been lost

due to deliberate destruction (Brown and Waterhouse-

Watson, 2014). Consequently, they only reveal a

small part of a bigger context. Interpreting this data

demands precision (Windhager et al., 2019; Liem

et al., 2023; Koller et al., 2009) and a heightened

awareness of how contemporary biases might influ-

ence our perceptions of the past (Prutsch, 2013).

Ethical Representation. Beyond accuracy and in-

tegrity, CH sites must also consider the ethical dimen-

sions associated with digitizing and representing tan-

gible and intangible historical assets (Man

ˇ

zuch, 2017;

Rich and Dack, 2022). When curating displays or

constructing narratives, it is typically necessary to

approach the subject with respect. This is particu-

larly true when recounting events that may have trau-

matic histories (Fisher and Schoemann, 2018). Digi-

tal recreations of tangible/intangible historical assets,

demand a balance between shedding light on histor-

ical facts and avoiding unintentional bias or misrep-

resentation, which, e.g., could arise from an uninten-

tionally biased perspective of the creator of the digital

recreations (Thompson, 2017) or due to uncertainty

related to the underlying historical assets. To try and

minimize these biases, creators need to reflect upon

their own biases and transparently reflect these to the

reader. Ultimately, an ethical obligation towards the

recipients is associated with the representation of dig-

itized tangible and intangible historical assets, and it

is an aspect that is crucial in digital storytelling at her-

itage sites, where there is a need to respect the com-

plexities and sensitivities of heritage narratives (Har-

good et al., 2023; Trichopoulos et al., 2023).

Physical & Temporal Constraints. Spatial and

temporal considerations inevitably influence story-

telling in the physical domain of heritage sites (Rossi

et al., 2017). The spatial arrangement of a heritage

A Survey on Storytelling Techniques for Heritage on Nazi Persecution

611

site can guide or even dictate the narrative flow (Be-

nouaret and Lenne, 2015; Lombardo and Damiano,

2012). Moreover, the narrative must be crafted con-

sidering visitors’ limited time at a site. The challenge

is to ensure that, within this brief window, visitors

gain a coherent and enriching understanding of the

narrative being presented.

Embracing Technology & Engaging the Senses.

CH sites have the unique potential to craft multisen-

sory experiences, unlike many traditional storytelling

mediums. For example, Katifori et al. (2018) high-

lights multi-sensory interactions’ transformative role

in enhancing visitor immersion, emphasizing the shift

towards emotive virtual experiences through person-

alized storytelling. In their research on the CHESS

prototype, Katifori et al. (2014) showcased how per-

sonalized, interactive digital storytelling experiences

can significantly elevate visitors’ experience. While

the potential of emotive virtual experiences in her-

itage sites is vast, there are also inherent challenges.

For example, an overemphasis on technology can

overshadow genuine historical value, potentially re-

ducing the experience to mere entertainment (Rich

and Dack, 2022). Some visitors might also feel that

digital augmentation hinders a direct connection with

heritage (Man

ˇ

zuch, 2017). As narratives become

more emotive, there is also a risk of modern biases

affecting the representation (Prutsch, 2013).

Educational Ambitions & Audience Diversity.

Heritage sites can be said to operate at the intersec-

tion of engagement and education. While the narra-

tives must be compelling, an underlying educational

mission seeks to inform and enlighten visitors about

historical, cultural, or scientific facets. Complicat-

ing this mission is the vast diversity of the audience.

With visitors spanning different age groups, cultural

backgrounds, and levels of prior knowledge, the sto-

rytelling needs to be inclusive and universally acces-

sible. As discussed by Mason (2004), communica-

tion models at heritage sites have traditionally empha-

sized a unilateral approach. In this model, the her-

itage professional is the transmitter, sending a singu-

lar, one-way message to the visitor. However, such a

method is limiting. For narratives to resonate with

visitors, they should be formulated with a holistic

understanding of the visitor’s context. This encom-

passes their background, including prior experiences,

learning styles, interests, and motivations; the socio-

cultural backdrop of their visit; and their interaction

with the heritage site’s spatial and tangible aspects

(Lombardo and Damiano, 2012; Rizvic et al., 2019).

8 DISCUSSION

We acknowledge the inherent limitations in our data

collection methodology, which primarily relied on

the storytelling instance collection efforts of MEM-

ORISE project members. This dependence on a sin-

gle source might limit the diversity of storytelling ex-

amples, consequently impacting the range of perspec-

tives and potentially affecting the validity of our find-

ings. Recognizing this constraint, we have taken steps

to ensure that the principles of our refined and aug-

mented design space, initially shaped by a specific

context, are adaptable to a broader spectrum of his-

torical and cultural events. This adaptability extends

beyond the historical scope of HNP during World War

II and includes various instances of persecution. For

instance, we imagine our design space could be ap-

plied in the context of different historical events re-

lating to persecution and oppression, e.g., ranging

from the prosecution of Black individuals in America

(Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, 2020)

to the situation in Uyghur camps in modern China

(Techjournalist, 2020). This applicability stems from

our design space’s reliance on universal storytelling

elements pertinent across the aforementioned histori-

cal and cultural contexts. These elements include but

are not limited to, specific image types (first/second-

hand images), text types (diaries, testimonies, and

official documents), and person types (victims, sur-

vivors, and persecutors), as well as place types (past

and present).

Nevertheless, applying our design space to con-

texts beyond those included in our initial study may

require additional modifications or considerations,

particularly as new storytelling methods evolve along-

side technological advancements (Chen et al., 2023).

We are aware of the potential biases introduced by

focusing primarily on HNP and relying on a single

source for our material. Therefore, we recommend

future research to expand the range of sources and

contexts. Doing so will not only improve the gen-

eralizability of our results but also contribute to the

continuous refinement and adaptation of our frame-

work, ensuring its relevance in diverse settings.

9 CONCLUSION

As CH departments play a pivotal role in communi-

cating the significance of historical sites to visitors,

the essence of this task lies in drawing lessons from

history. Understanding and acknowledging past mis-

takes and preserving memories take on heightened

importance in the contemporary context. This im-

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

612

perative underscores the enduring relevance of CH

in fostering awareness, learning, and reflection. As

we navigate the complexities of VS in conveying his-

torical narratives, the enduring mission remains clear:

to bridge the past with the present, ensuring that the

lessons embedded in CH sites resonate with and guide

future generations.

In an ever-evolving media environment, the im-

perative to develop an agile design space, adaptable

to changing needs, is more critical than ever. Reflect-

ing on the existing VBS design space and the insights

obtained from our survey, certain key considerations

emerge for advancing design implementations in CH

contexts. The augmented design space, working in

tandem with the original VBS framework, offers a

comprehensive guide for enhancing communication

at CH sites.

This dynamic interplay between design spaces not

only serves to refine current practices but also sheds

light on novel challenges. Identifying these chal-

lenges opens avenues for fresh perspectives in de-

signing strategies’ ongoing development and itera-

tion. Thus, our study contributes to the evolving dis-

course on VS in CH and provides a roadmap for future

endeavors, ensuring that the rich tapestry of historical

narratives continues to engage and resonate with di-

verse audiences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work, part of a project funded by the EU’s Hori-

zon Europe research and innovation program (grant

agreement No. 101061016), reflects only the authors’

views. The European Commission is not responsible

for any use of the information herein, nor does it rep-

resent the Commission’s official stance.

REFERENCES

Arolsen Archives (2022). StolenMemory. URL: https://ww

w.stolenmemory.org/en/. Visited: 2023-11-02.

art.vision (2020). Mahn- und Gedenkst

¨

atte - art.vision.

URL: https://art.vision/mahn-und- gedenkstaette.

Visited: 2023-12-12.

Ba

´

nkowska, A., Citrigno, F., and Kreutzm

¨

uller, C. (2023).

Statistics Catastrophe Questioning Eichmann’s num-

bers. URL: https://www.ghwk.de/statisticsandcatastr

ophe/. Visited: 2023-10-27.

Benouaret, I. and Lenne, D. (2015). Personalizing the mu-

seum experience through context-aware recommenda-

tions. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Sys-

tems, Man, and Cybernetics, pages 743–748. IEEE.

BMDMF (Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials

Foundation) (2021). #otd1945 - Liberation Buchen-

wald & Mittebau-Dora. URL: https://liberation.buche

nwald.de/en/otd1945. Visited: 2023-11-03.

Boyd Davis, S., Vane, O., and Kr

¨

autli, F. (2021). Can

i believe what i see? data visualization and trust

in the humanities. Interdisciplinary science reviews,

46(4):522–546.

Bradley, R. (2005). Digital authenticity and integrity: Dig-

ital cultural heritage documents as research resources.

Portal (Baltimore, Md.), 5(2):165–175.

Brown, A. and Waterhouse-Watson, D. (2014). The fu-

ture of the past: Digital media in holocaust museums.

Holocaust studies, 20(3):1–32.

Campscapes Westerbork (2022). Westerbork Viewer. URL:

https://data.campscapes.org/westerbork-test/. Visited:

2023-10-27.

Chen, Q., Cao, S., Wang, J., and Cao, N. (2023). How

does automation shape the process of narrative visu-

alization: A survey of tools. IEEE transactions on

visualization and computer graphics, PP:1–20.

Chenchanna, D. and Gogelein, Y. (2022). Haus der

Wannsee-Konferenz. URL: https://entdeckungstou

r.zdf.de. Visited: 2023-11-04.

Deinert, E. and Maier, Y. (2020). The Liberation. URL:

https://diebefreiung.br.de. Visited: 2023-11-03.

Dive Project (2023). Keeping Memories. URL: https://keep

ingmemories.gedenkstaette-flossenbuerg.de. Visited:

2023-11-04.

Europa-Universit

¨

at Viadrina (2023). Unbekannte Orte.

Ravensbr

¨

uck - Eine digitale Spurensuche. URL: https:

//unbekanntes-ravensbrueck.de/. Visited: 2023-10-

27.

Fisher, J. A. and Schoemann, S. (2018). Toward an Ethics of

Interactive Storytelling at Dark Tourism Sites in Vir-

tual Reality, volume 11318 of INTERACTIVE STO-

RYTELLING, ICIDS 2018, pages 577–590. Springer

International Publishing, Cham.

Genette, G. (1983). Narrative Discourse: An Essay in

Method. Cornell University Press.

Gershon, N. and Page, W. (2001). What storytelling can

do for information visualization. Commun. ACM,

44(8):31–37.

Hargood, C., Millard, D. E., Mitchell, A., and Spierling,

U. (2023). An Ethics Framework for Interactive Digi-

tal Narrative Authoring, pages 335–351. The Author-

ing Problem. Springer International Publishing AG,

Switzerland.

Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation (2020). The

Struggle for African American Freedom. URL: https:

//artsandculture.google.com/story/the-struggle- f

or-african-american-freedom/VAUh-GjK9Fx4KA.

Visited: 2024-01-11.

Isberner, M.-B., Richter, T., Maier, J., Knuth-herzig, K.,

Horz, H., and Schnotz, W. (2013). Comprehending

conflicting science-related texts: graphs as plausibil-

ity cues. Instructional Science, 41(5):849–872.

JMB (Jewish Museum Berlin) (2013). J

¨

udisches Museum

Berlin: Online-Schaukasten - 1933. URL: https://ww

w.jmberlin.de/1933/. Visited: 2023-12-12.

A Survey on Storytelling Techniques for Heritage on Nazi Persecution

613

JMB (The Jewish Museum Berlin) (2023). Topography of

Violence 1930–1938. URL: https://www.jmberlin.de/

topographie-gewalt/#/en/info. Visited: 2023-11-04.

Katifori, A., Karvounis, M., Kourtis, V., Kyriakidi, M.,

Roussou, M., Tsangaris, M., Vayanou, M., Ioannidis,

Y., Balet, O., Prados, T., Keil, J., Engelke, T., and Pu-

jol, L. (2014). Chess: Personalized storytelling ex-

periences in museums. In Mitchell, A., Fern

´

andez-

Vara, C., and Thue, D., editors, Interactive Story-

telling, pages 232–235, Cham. Springer International

Publishing.

Katifori, A., Roussou, M., Perry, S., Drettakis, G., Vizcay,

S., and Philip, J. (2018). The emotive project-emotive

virtual cultural experiences through personalized sto-

rytelling. In Cira@ euromed, pages 11–20.

Kim, N. W., Bach, B., Im, H., Schriber, S., Gross, M., and

Pfister, H. (2018). Visualizing nonlinear narratives

with story curves. IEEE Transactions on Visualiza-

tion and Computer Graphics, 24(1):595–604.

Kochavi, M. and Kochavi, M. (2019). Eva (@eva.stories).

URL: https://www.instagram.com/eva.stories/. Vis-

ited: 2023-11-03.

Koller, D., Frischer, B., and Humphreys, G. (2009). Re-

search challenges for digital archives of 3d cultural

heritage models. Journal on computing and cultural

heritage, 2(3):1–17.

Kusnick, J., J

¨

anicke, S., Doppler, C., Seirafi, K., Liem, J.,

Windhager, F., and Mayr, E. (2021). Report on narra-

tive visualization techniques for opdb data. Technical

report, European Comission.

Latif, S., Chen, S., and Beck, F. (2021). A deeper

understanding of visualization-text interplay in geo-

graphic data-driven stories. Comput. Graph. Forum,

40(3):311–322.

Liem, J., Slingsby, E., Goudarouli, E., Bell, M., Turkay,

C., Perin, C., and Wood, J. (2023). Visualising the

uncertain in heritage collections: understanding, ex-

ploring and representing uncertainty in the first world

war british unit war diaries. Literary Geographies,

9(1):101–123.

LMUM (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universit

¨

at M

¨

unchen)

(2018). Munich Project ’LediZ’ - Learning with

digital testimonies (LediZ) - LMU Munich. URL:

https://www.en.lediz.uni-muenchen.de/projekt-lediz/i

ndex.html. Visited: 2023-12-12.

Lombardo, V. and Damiano, R. (2012). Storytelling on mo-

bile devices for cultural heritage. The new review of

hypermedia and multimedia, 18(1-2):11–35.

Man

ˇ

zuch, Z. (2017). Ethical issues in digitization of cul-

tural heritage. Journal of Contemporary Archival

Studies, 4(2):4.

Mason, R. (2004). Museums, galleries and heritage: Sites

of meaning-making and communication, pages 221–

237. Heritage, Museums and Galleries: An Introduc-

tory Reader. Routledge.

McKenna, S., Henry Riche, N., Lee, B., Boy, J., and Meyer,

M. (2017). Visual narrative flow: Exploring factors

shaping data visualization story reading experiences.

Comput. Graph. Forum, 36(3):377–387.

Melian, M. (2010). Memory loops. URL: https://www.me

moryloops.net. Visited: 2023-11-04.

M

¨

uller, K. (2002). Museums and virtuality. Curator (New

York, N.Y.), 45(1):21–33.

O’Neill, K. and Jongsma, E. (2021). His Name Is My

Name. URL: https://jongsmaoneill.com/immersiv

e/his-name-is-my-name/. Visited: 2023-11-03.

Prutsch, M. J. (2013). European historical memory: Poli-

cies, challenges and perspectives. Technical report,

EPRS: European Parliamentary Research Service.

Rich, J. and Dack, M. (2022). Forum: The holocaust in

virtual reality: Ethics and possibilities. The Journal of

Holocaust Research, 36(2-3):201–211.

Rizvic, S., Boskovic, D., Okanovic, V., Sljivo, S., and

Zukic, M. (2019). Interactive digital storytelling:

bringing cultural heritage in a classroom. Journal

of computers in education (the official journal of the

Global Chinese Society for Computers in Education),

6(1):143–166.

RLEGL (Region L

¨

uneburg und Euthanasie-Gedenkst

¨

atte

L

¨

uneburg e.V., 2022) (2022). T4 – geschichte raum

geben. URL: https://geschichte-raum-geben.de/t4/.

Visited: 2023-10-02.

Rosenberger, R. (2018). Zeitzeugenportal: Erz

¨

ahlen. Erin-

nern. Entdecken. URL: https://www.zeitzeugen-porta

l.de/. Visited: 2023-12-12.

Rossi, S., Barile, F., Galdi, C., and Russo, L. (2017).

Recommendation in museums: paths, sequences, and

group satisfaction maximization. Multimedia tools

and applications, 76(24):26031–26055.

Roth, R. E. (2021). Cartographic design as visual sto-

rytelling: Synthesis and review of map-based narra-

tives, genres, and tropes. The Cartographic Journal,

58(1):83–114.

Rudnick, C. S. (2022). Zwangssterilisation – Geschichte

Raum geben. URL: https://geschichte-raum-geben.d

e/zwangssterilisation/. Visited: 2023-11-02.

Santana Quintero, M., Awad, R., and Barazzetti, L. (2020).

Harnessing digital workflows for the understanding,

promotion and participation in the conservation of

heritage sites by meeting both ethical and technical

challenges. Built heritage, 4(1):6–18.

Segel, E. and Heer, J. (2010). Narrative visualization:

Telling stories with data. IEEE Transactions on Visu-

alization and Computer Graphics, 16(6):1139–1148.

Stolper, C. D., Lee, B., Henry Riche, N., and Stasko, J.

(2016). Emerging and recurring data-driven story-

telling techniques: Analysis of a curated collection of

recent stories. Technical Report MSR-TR-2016-14,

Microsoft Research.

Stræde, T. and Hansen, P. M. (2018). De danske jøder i

Theresienstadt - Litteratur. URL: https://www.dani

shjewsintheresienstadt.org/litteraturliste?lang=en.

Visited: 2023-11-03.

Techjournalist (2020). Open-source satellite data to inves-

tigate Xinjiang concentration camps. URL: https:

//techjournalism.medium.com/open-source-satelli

te-data-to-investigate-xinjiang-concentration-camps

-2713c82173b6. Visited: 2024-01-11.

IVAPP 2024 - 15th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

614

Thompson, E. L. (2017). Legal and ethical considerations

for digital recreations of cultural heritage. Chap. L.

Rev., 20:153.

Tong, C., Roberts, R., Borgo, R., Walton, S., Laramee,

R. S., Wegba, K., Lu, A., Wang, Y., Qu, H., Luo, Q.,

et al. (2018). Storytelling and visualization: An ex-

tended survey. Information, 9(3):65.

Trichopoulos, G., Alexandridis, G., and Caridakis, G.

(2023). A survey on computational and emergent dig-

ital storytelling. Heritage, 6(2):1227–1263.

Vancisin, T., Clarke, L., Orr, M., and Hinrichs, U.

(2023). Provenance visualization: Tracing people,

processes, and practices through a data-driven ap-

proach to provenance. Digital Scholarship in the Hu-

manities, 38(3):1322–1339.

WDR (2023). Stolpersteine NRW - an app for remember-

ing. URL: https://stolpersteine.wdr.de/web/en/. Vis-

ited: 2023-11-04.

Wehnen Memorial (2021). Traces on paper - Wehnen

Memorial. URL: https://gedenkstaette-wehnen.de

/spuren-auf-papier/. Visited: 2023-11-04.

WHO (2011). World report on disability. WHO library

Cataloguing in-publication Data.

Windhager, F., Salisu, S., and Mayr, E. (2019). Exhibit-

ing uncertainty: Visualizing data quality indicators for

cultural collections. Informatics (Basel), 6(3):29.

Yad Vashem (2023). Transports to Extinction: Holocaust

(Shoah) Deportation Database. URL: https://collecti

ons.yadvashem.org/en/deportations. Visited: 2023-

10-27.

Zhao, Z. and Elmqvist, N. (2023). The stories we tell about

data: Surveying data-driven storytelling using visual-

ization. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications,

43(4):97–110.

A Survey on Storytelling Techniques for Heritage on Nazi Persecution

615