Systematization of Competence Assessment in Higher Education:

Methods and Instruments

Sina Marie Lattek, Linn Rieckhoff, Georg Völker, Lisa-Marie Langesee

a

and Alexander Clauss

b

Chair of Business Information Systems – Information Management,

Faculty of Business and Economics TU Dresden, Germany

Keywords: Key Competencies, Competence Assessment, Systematization, Higher Education, Assessment Instruments,

Assessment Methods.

Abstract: In a time of increasing digitalization, internationalization, and globalization, accompanied by corresponding

adjustments and transformations, a central Higher Education (HE) objective is to prepare students for the

professional world effectively. This is achieved through the continuous development of students'

competencies. To facilitate this ongoing process, there is a need to streamline the assessment of key

competencies in academic courses. This paper addresses this by conducting a systematic literature review

(SLR) and subsequent expert interviews to comprehensively document and systematically analyze the

methods and instruments employed in assessing students' key competencies in HE. This systematic analysis

serves as a valuable decision-making aid and a source of inspiration for educators seeking to integrate

competency-specific methods and instruments into their courses. Additionally, differences and parallels

between theoretical literature and practical application are highlighted.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the era of increasing digitalization,

internationalization, and globalization, adjustments

and changes in HE are also intensifying (Blank et al.,

2023; Mrohs et al., 2023). In this context, a central

objective of HE institutions is to prepare students for

the upcoming professional world, particularly

regarding their competencies, including the so-called

key competencies, as effectively as possible (Saas,

2023). Not only do the required competencies of

students continuously evolve, but also the formats of

examinations and assessment methods for measuring

competencies adapt to the changing demands (Porsch

& Reintjes, 2023). It is crucial to note that an

appropriate evaluation or assessment method should

be selected for each key competency acquired and

developed by a student during their university

journey. Only through a high alignment between the

key competency under examination and the chosen

assessment method can targeted development and

evaluation of these competencies be achieved (Saas,

2023). This research paper addresses this point and

provides an approach to systematize selected key

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3053-7701

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0668-3140

competencies in HE along with suitable assessment

methods and instruments.

For the elaboration and categorization, it is

essential to establish a unified understanding of

terminologies and to delineate them from similar

terms. The primary focus within the present work lies

on the terms key competencies, methods, and

instruments. When elaborating on key

competencies, it becomes evident that a unified

concept or understanding has not yet been achieved

(e.g., Orth, 1999; Krüger, 1988; Weinert, 2001). This

is partly attributed to the metaphorical nature of the

term (Mugabushaka, 2004). Orth (1999) defines key

competencies as acquirable general abilities,

attitudes, and elements of knowledge that are useful

in solving problems and acquiring new competencies

in as many content areas as possible. The present

research work builds on this understanding while

complementing it with the HE context. In addition to

Orth, models proposed by Krüger (1988), Mertens

(1991), Welbers (1997), Münch (2001), Weinert

(2001), and Chur (2002) further contribute to defining

the term in relation to HE. Through a comparison of

existing models, the following essential key

Lattek, S., Rieckhoff, L., Völker, G., Langesee, L. and Clauss, A.

Systematization of Competence Assessment in Higher Education: Methods and Instruments.

DOI: 10.5220/0012577500003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 2, pages 317-326

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

317

competencies in HE emerge (s. Table 1), serving as

the subject of investigation in this study.

Table 1: Overview of the most relevant key competencies

of students.

1. Critical Thinking 5. Digital Competence

2. Communication

Com

p

etence

6. Self-Reflection and

Metaco

g

nition

3. Self-Management and

Time Management

7. Intercultural

Competence

4. Teamwork and Social

Com

p

etence

8. Creativity and Problem-

Solvin

g

When defining competencies, it is important to

distinguish it from the term »skills« or »abilities«.

Skills describe specific, learnable actions, while

competencies encompass a broad spectrum of skills,

knowledge, and attitudes that can be applied in

complex situations (Hain, 2019). In the context of

assessing and evaluating key competencies, methods

refer to procedures and approaches used for

competency assessment. At the same time,

instruments represent the specific tools or measures

employed within these methods to assess and measure

competencies. Methods determine the framework and

structure of the assessment, while instruments

constitute the specific elements used within this

framework to collect data and assess competencies

(Galuske, 2013; Geißler & Hege, 2007).

Looking at the key competencies to be

investigated, it becomes clear that all thematically

relevant papers address only isolated key

competencies, and thus, a comprehensive overall

view is lacking. Furthermore, only individual

methods and instruments are addressed in each case,

and a comprehensive linking or assignment of

multiple forms is only done in specific instances and

not thoroughly. This justifies the need for a

comprehensive presentation and assignment of key

competencies and corresponding assessment methods

to close this research gap.

As the current state of research indicates, no

existing approaches systematically consolidate

methods and instruments for assessing students' key

competencies. The relevant papers primarily

investigate individual key competencies using

quantitatively measurable approaches. These

approaches include conducting surveys using

instruments such as multiple-choice, self-assessment,

and short questions to determine the development of

knowledge and competencies within a predefined

period and subsequently statistically analyze them.

This approach is employed by various researchers

(e.g., Brasseur et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2016; Stanley

& Bhuvaneswari, 2016; Soeiro, 2018; Lucas et al.,

2022). Selected instruments for competency

assessment are detailed in the works of Bray et al.

(2020); Birdman et al. (2021); Van Helden et al.

(2023); Pavlasek et al. (2020); Heymann et al. (2022);

and Lucas et al. (2022) for measuring specific key

competencies. However, only a few assessment

methods are recurrently mentioned in the literature.

Additional methods, like portfolios, storytelling, or

presentations, are employed by Caratozzolo et al.

(2022); Kleinsorgen et al. (2021); and Squarzoni &

Soeiro (2018) for competency measurement.

Moreover, all papers focus on different scientific

and university domains, often with a specialized

emphasis. Therefore, a comprehensive overview of

the entire HE sector can only be achieved by

consolidating all research papers.

As mentioned, not every key competency can be

assessed and measured using the same assessment

method or instrument. Considering the existing

research field, it can be inferred that a suitable

assignment or systematization is currently lacking,

making precise selection of suitable methods and

instruments more challenging for educators. The

assessment of key competencies no longer aligns

effectively with one-size-fits-all solutions such as

traditional exams. Educators lack guidance on which

methods and instruments to employ as assessment

formats for various key competencies. This research

addresses this gap and introduces an initial

framework for a concrete decision guide to

systematize diverse assessment formats for each key

competency. This aim leads to the following research

questions (RQ):

RQ 1: What methods and instruments are

employed for assessing students’ key competencies in

HE teaching?

RQ 2: What differences exist between the

practice and the literature in their usage?

RQ 3: How can instruments and methods for

explicitly applying and assessing key competencies

be systematized?

To address the research questions, the explanation

of the methodological approach follows the

introduction. This section elaborates on the research

methods of SLR and guided expert interviews. The

methods were chosen to establish a robust theoretical

foundation using an SLR and, subsequently, to

conduct guideline-based interviews to complement

practical insights. The data analysis and synthesis are

conducted following the frameworks provided by

Kitchenham (2004) and Kuckartz & Rädiker (2022).

The results from the SLR and expert interviews are

systematized and presented in the third part of the

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

318

paper. Subsequently, the discussion section critically

examines possible conclusions, includes a decision

guide for educators, and derives recommendations for

action. The paper concludes by addressing the study's

limitations and providing an outlook.

2 METHODOLOGY

The present study consists of two qualitative

approaches, the SLR and the following guided expert

interviews, to address the research questions. The

SLR was necessary to provide a solid foundation in

the literature for reviewing and analyzing existing

research to provide the basis for a well-prepared

qualitative analysis. Expert interviews were chosen as

a method to compare and enrich the results from the

literature with the experiential insights of

practitioners.

2.1 Systematic Literature Research

Systematizing methods and instruments for capturing

students' competencies requires an interdisciplinary

analysis of existing research findings. Therefore, an

SLR was conducted, utilizing the framework

provided by Kitchenham (2004). The framework is

structured into three phases:

Planning: Specification of the research question,

development, and validation of the research protocol.

Execution: Identifying relevant research,

selecting primary studies, evaluating study quality,

extracting data, synthesizing data.

Documentation: Assessment report and

validation.

For the analysis, four databases from the disciplines

of Computer Science and Communication (IEEE

Xplore), Psychology and Sociology (APA Psycinfo),

and Higher Education (IBZ Online and Academic

Search Elite) were employed to ensure a broad search

field. The databases were chosen thematically in line

with the research questions. The following search

string was used:

»Methods OR Tools OR Instruments OR

Measures OR Techniques (AND) Key Competences

OR Core Competences OR Key Skills OR Core Skills

(AND) Assessment OR Evaluation OR Rating OR

Analysis OR Estimation (AND) higher AND

Education«

The search was restricted to the period from 2013

to 2023 to account for possible changes in methods

and instruments over time. The selection of

publications was made in both English and German.

To objectively select publications based on titles

and abstracts, criteria were formulated, requiring

explicit mention of key competencies, methods,

and/or instruments for capturing key competencies, as

well as an academic context. The full-text analysis

was based on five key points: methods and

instruments used, prerequisites, application,

advantages and disadvantages, and addressed key

competencies. Full texts that included the five basic

criteria were selected for the present study.

Additional criteria that were also considered included

consideration of sample sizes, research environment,

journal rankings, and methodology.

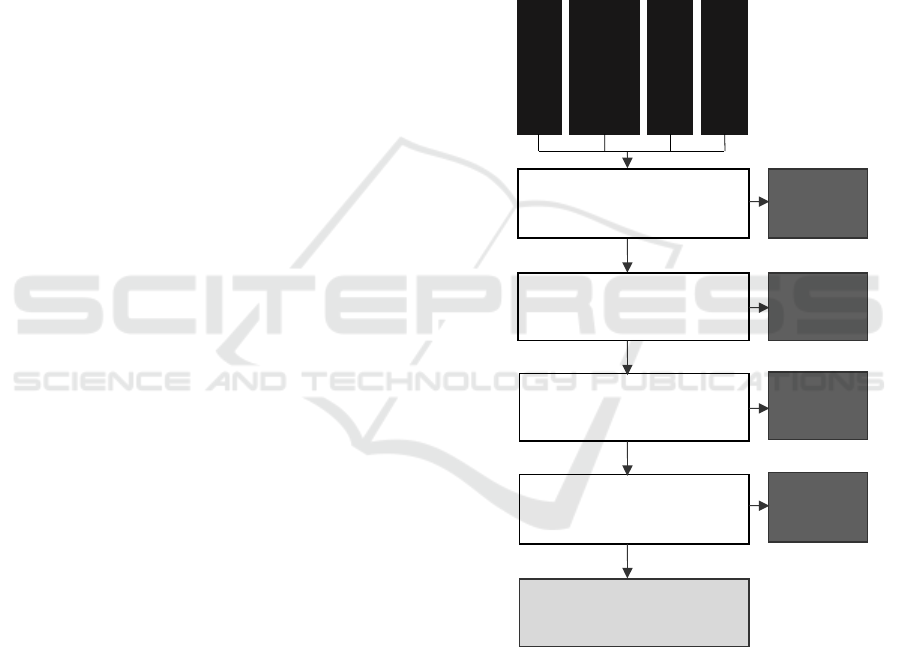

Figure 1: SLR Results.

2.2 Guideline-Based Expert Interviews

For comparison and enrichment of the results from

the literature, interviews with experts from the field

were conducted (Misoch, 2015). Experts were

selected based on their specialized expertise and

practical experience in their respective areas, as well

as on the recommendation of a research network.

Additionally, they were required to meet one or more

of the following criteria:

Excluded

(n = 1)

Excluded

(n = 299)

Excluded

(n = 81)

Excluded

(n = 26)

IEEExplore

(n = 162)

Academic

Search Elite

(n = 129)

IBZ Online

(n = 37)

PsycInfo

(n = 93)

After removing duplicates

(n = 421)

Relevant by title

(n = 122)

Relevant by abstract

(n = 41)

Relevant by full text

(n = 15)

Relevant literature by

further research

(n = 4)

Systematization of Competence Assessment in Higher Education: Methods and Instruments

319

• Engagement in HE teaching,

• Consulting or academic employment,

• In-depth experience in capturing students'

competencies,

• Contribution to the development of didactic

tools.

In this context, and due to their suitability for the

topic, four people covering areas such as information

management, e-learning within interdisciplinary

learning, program development, and digital

innovation and participation were chosen as experts.

The interviews took place from 19

th

- 24

th

October

2023, using the recording function of Microsoft

Teams. The interviews were guided by a

questionnaire covering aspects such as personal

background, experiences, expertise in the subject

matter, and additional insights for the research.

Subsequently, the approach by Kuckartz & Rädiker

(2022) and the software MAXQDA were applied for

data analysis and synthesis, utilizing the structuring

qualitative content analysis method. All derived

results will be listed in the online appendix. The

material underwent several coding cycles with

inductively formed categories (Appendix A). The

preliminary material processing involved

transcription using the smoothing transcription rules,

according to Dresing & Pehl (2018). The process is

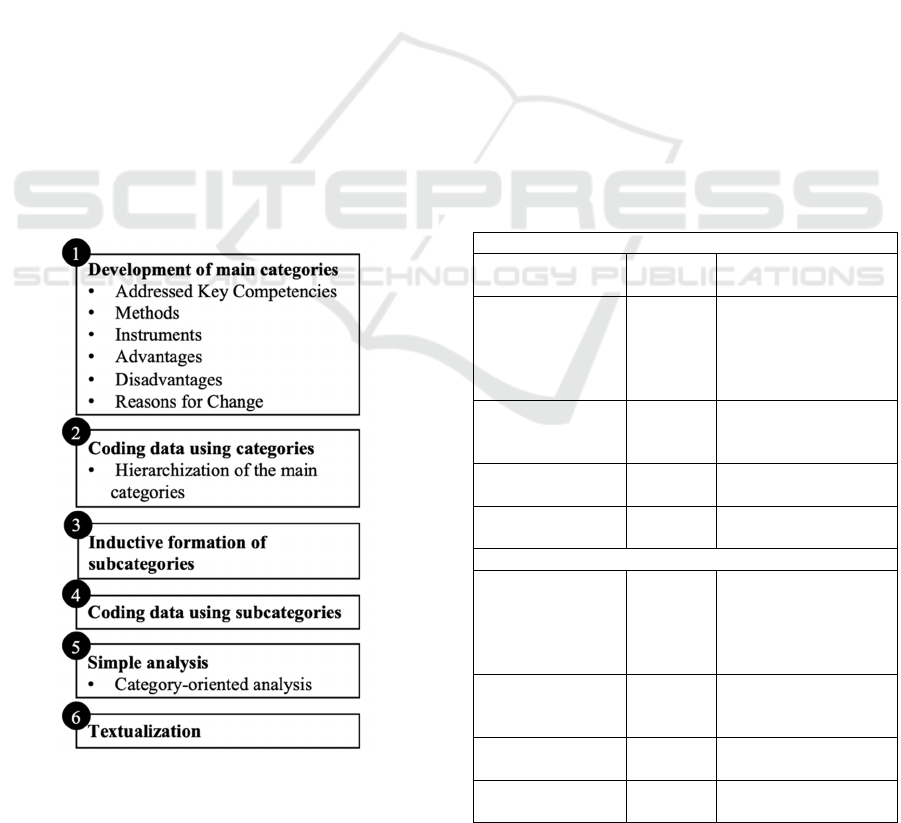

portrayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Structure of qualitative content analysis

Kuckartz & Rädiker (2022).

3 RESULTS

The results from the SLR and interviews are

presented in the following chapters, along with the

derived systematization of methods and instruments

for competence assessment.

3.1 SLR Results

The SLR analysis fundamentally enabled the focus on

eight key competencies within higher education,

derived from their frequency of mention in the

publications (Appendix D and Appendix E).

Furthermore, through the SLR analysis, existing

instruments and methods for capturing students’ key

competencies were identified. The examined

publications addressed existing competency

assessment methods (twelve publications) or existing

instruments (14 publications). However, there were

partial overlaps between these publications (nine

publications). In delineating the methods and

instruments, their categorization into different

formats (written, oral, physical presence, digital,

asynchronous, observation) was realized. The

application forms and examples of identified methods

and instruments are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Literature - Identified Methods and Instruments.

Methods

Format Papers/

Mentions

Associated Methods

Written 8 / 16

Case study work (P8);

Essay (P9, P10, P13,

P14); hands-on practice

(P13, P14); Peer

Review (P9)

Oral 5/ 6

Group examination

(P2); Reflection

discussion

(

P19

)

Physical presence 3 / 4

Experiment (P8);

Discussion (P10)

Observation 3 / 4

Observation in seminar

(P15, P17)

Instruments

Written 12 / 21

Multiple Choice (P1,

P5, P8, P11, P13, P14);

Reflection sheets (P15),

(P16, P18); Likert Scale

(P1, P3, P7)

Digital 5 / 6

Simulation (P2);

Multiple Choice (P4,

P13, P14

)

Asynchronous

1 / 1

Self-assessment

questions (P5)

Observation 1 / 1

Observation protocol

(P15)

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

320

The identified methods for competency

assessment included the formats of »Written«,

»Oral«, »Physical presence«, and »Observation«.

Conversely, for the instruments, the formats

»Written,« »Digital,« »Asynchronous« and

»Observation« were delineated. The overview

showed that the publications concerning the listed

methods emphasized the written assessment formats.

Eight publications (with a total of 16 mentions)

focused on this format. A similar outcome was

observed for the format of the investigated

instruments in the publications. Twelve publications

(totaling 21 mentions) addressed the written format of

competency assessment instruments (Table 3).

3.2 Expert Interviews

The four interviews (I1, I2, I3, and I4) with experts

from the field confirmed various findings from the

literature or supplemented them with practical

experience. This validation from the interviewees

enriched the selection of key competencies derived

from the analysis of the SLR (Table 4) based on their

practical insights. Furthermore, an evaluation was

conducted to determine if the application formats of

methods and instruments for competency assessment

align with the results of the SLR analysis (Appendix

B). This alignment was partially confirmed. Similar

to the SLR analysis, the interviewees listed the

application formats »Written,« »Oral,«

»Presentation,« and »Observation« for the methods.

However, these results were supplemented by the

interviews with the formats »Digital« and

»Asynchronous«. The focus on the mentioned

methods was on written methods (37 mentions), oral

methods (29 mentions), and methods conducted in

physical presence (24 mentions) among the

interviewees. For the instruments, the interview

results included the application formats »Written«

and »Observation,« similar to the SLR analysis.

However, these were supplemented by »Digital« and

»Asynchronous,« with the application forms »Oral«

and »Presentation« being excluded. The focus was on

the written formats of instruments (14 mentions).

Within the listed formats, additional methods and

instruments were derived from the interviews (Table

4).

Table 4: Interviews - Identified Methods and Instruments.

Methods

Format

Interviews/

Mentions

Associated Methods

Written 4 / 37

Peer Reviews (I1, I2,

I3); Exam (I1, I2, I3);

Portfolio (I1, I3, I4)

Oral 4 / 29

Discussion (I1, I2, I4);

Group examination (I1,

I2, I4); (Deep-)

Interview (I2, I4)

Digital 3 / 12

Blogpost (I1); Flipped

Classroom (I1, I4);

Presentation (I1)

Physical

presence

4 / 24

Reflection discussion

(I1, I2); Group

examination (I1, I4);

Oral Exam (I2, I3, I4)

Asynchronous

3/ 9

Video tutorial (I1);

Blogpost (I1); Home-

and seminar work (I3,

I4

)

Observation 3 / 4

Observation in digital

interaction traces (I1,

I4); Scientific practical

examination

(

I3

)

Instruments

Written 3 / 14

Multiple Choice (I1,

I3, I4); DigCompEdu

(I1, I4); Self-

assessment questions

(

I1, I4

)

Digital 2 / 3

Simulation (I2);

Multi

p

le Choice

(

I1

)

Asynchronous

2 / 2

Self-assessment

questions (I1, I4)

Observation 2 / 5

Rubric matrix (I1);

Observation sheets

(I4); Social Learning

Analytics (I1, I4)

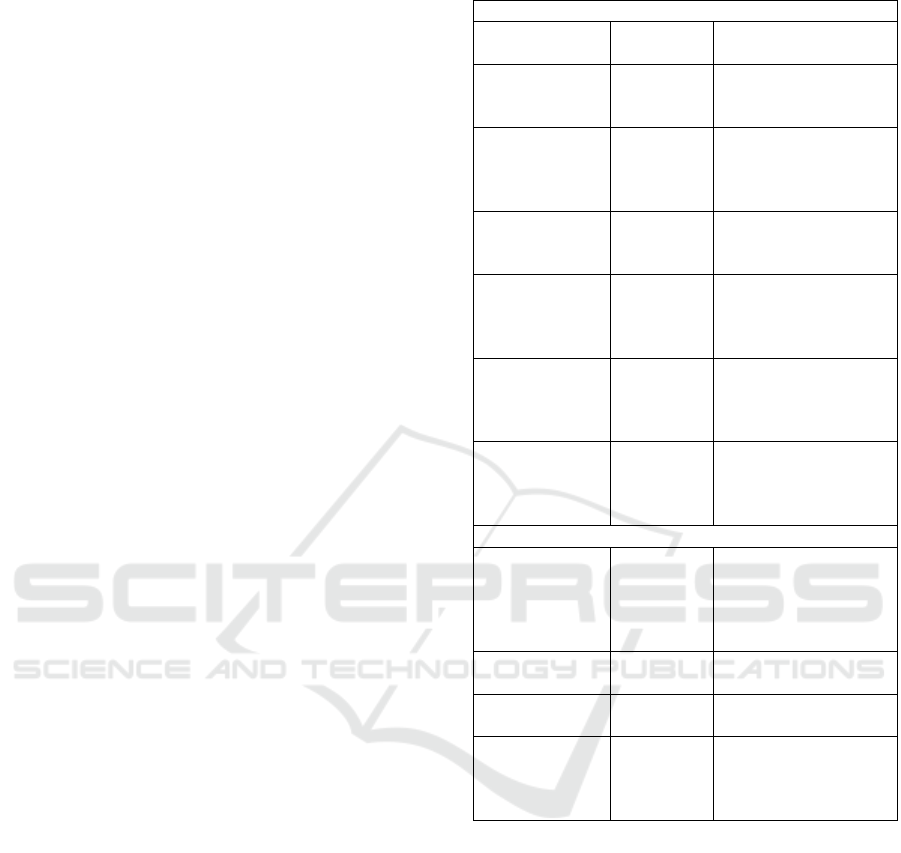

3.3 Systematization for Competence

Assessment

The systematization aims to associate methods and

instruments for assessing students' competencies with

the corresponding key competencies. Thus, the

systematization allows the selection of appropriate

methods and instruments based on the identified key

competencies. As a preliminary step to the

systematization, the results of the SLR analysis and

the interviews were summarized and organized in a

case-category matrix (Appendix B). The basic

structure of the case-category matrix is presented in

Table 5, showing the main categories, and the

specified subcategories 1 and 2 (Kitchenham, 2004;

Systematization of Competence Assessment in Higher Education: Methods and Instruments

321

Okoli & Schabram, 2010). The complete listing of all

categories from Table 5 can be found in Appendix B.

Table 5: Basic Structure of the Case-Category Matrix.

Methods

Main Sub 1 Sub 2

Addressed key

competence

Listing of key

competences

-

Methods

Application

forms

Breakdown of

the methods

Instruments

Application

forms

Breakdown of

the instruments

Advantages

Breakdown of

the advantages

-

Disadvantages

Breakdown of

the advanta

g

es

-

Reasons for

change

Breakdown of

the reasons for

change

-

The cases represent the examined interviews or

publications. The categories are further subdivided

into subcategories, which emerged during the coding

of the interviews and were accordingly applied for

evaluating the publications. The main categories

outline the critical points highlighted by the

publications or interviewees so that, in addition to the

mentioned key competencies, methods, and

instruments, the identification of advantages,

disadvantages, and reasons for change could also be

identified. In subcategories 1 and 2, the main

categories were specified. Using the case-category

matrix, the results of the literature and interviews

were compared, and the methods and instruments

were categorized accordingly, leading to the

derivation of the systematization. However,

advantages, disadvantages, and reasons for the

change were not included in the derivation of the

systematization, as these results were incorporated to

understand why specific methods and instruments

were listed.

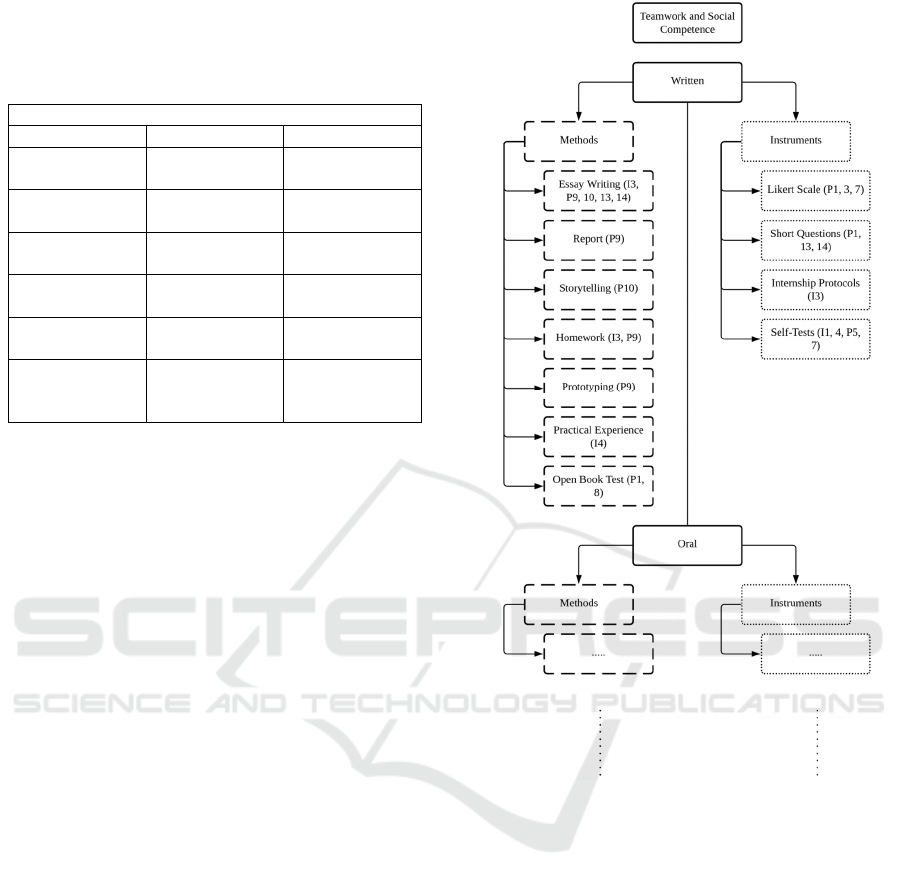

The derived systematization (Figure 3) represents

a decision matrix specifying which instruments or

methods are suitable for capturing key competencies

(Appendix C). It also indicates the formats in which

these methods and instruments can be applied. Thus,

it is possible to derive the appropriate methods and

instruments based on the desired key competencies.

The systematization compares literature and practice,

allowing users to distinguish which approach best

suits their intended goal.

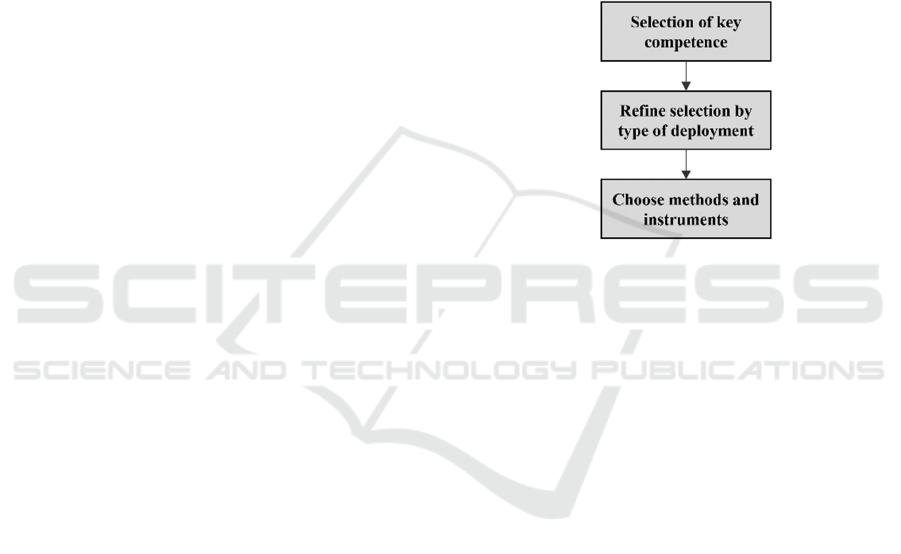

Figure 3: Systematization for Competence Assessment.

4 DISCUSSION

The interviews with experts from the field confirmed

the relevance of systematizing methods and

instruments for capturing students' competencies. As

the results showed, the demands for competency

assessment have increased in the last ten years due to

digitalization and globalization (I1), as well as higher

interdisciplinarity (I1; I3), and the shift to the new

generation of Digital Natives in the workplace (I1;

I4).

The results from the SLR and interviews with

experts in the field allowed for identifying various

methods and instruments for capturing students' key

competencies. Furthermore, the formats of these

methods and instruments were outlined. Additionally,

eight key competencies were defined for this work,

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

322

focusing on those emphasized in both literature and

practice. Developing key competencies and suitable

methods and instruments for their assessment

facilitated answering RQ 1. The results also led to the

derivation of a corresponding systematization in the

form of a decision matrix addressed to HE instructors,

thus addressing RQ 3. Within the systematization, the

results were categorized based on their origin

(literature or practice), addressing RQ 2 and

facilitating a comparison between literature and

practice. The results highlight several factors to

consider within the systematization. On the one hand,

the listed methods or instruments can be utilized for

multiple key competencies, assessing several

competencies with a single method or instrument, and

making them versatile. For example, the method of

Practical Exercise can address the following

competencies: self-reflection, creativity and problem-

solving, critical thinking, communication, teamwork,

and social competence (Appendix C). Instruments

like the Likert Scale can also be employed for various

competency assessments (Appendix C).

On the other hand, the interviews revealed that the

chosen key competencies sometimes overlap, and a

complete separation is not always possible. This is

because key competencies in HE are viewed from

different perspectives, highlighting various aspects

and divisions (I1). Therefore, it is recommended to

use different methods and instruments to cover a

broad spectrum of competencies.

As outlined in the Chapters 3.1 and 3.2, the results

of the literature and interviews also showed a strong

focus on written formats of methods and instruments

for competency assessment. Reasons for this include

reducing the effort (I1, I2, I4) of competency

assessment and being able to provide the necessary

human resources (I3). Furthermore, methods and

instruments of this format allow for a more accurate

and objective assessment of competencies (I1) and a

direct assignment to the respective individuals (I1).

Additionally, the results indicated that individual

methods and instruments were mentioned more

frequently in practice than in the literature (Appendix

C). Even though there was greater diversity in

methods in practice, it was clear that some methods

were only applied in limited timeframes or specific

course contexts (I3). The application of the

systematization presents certain challenges that need

to be considered for using methods and instruments.

For example, inhibitory data protection regulations

for competency assessment forms (I1, I4) or

increased effort in implementation (I1, I3, I4). The

personnel resources for more competency orientation

in the course pose a challenge (I2, I4) and the higher

time expenditure for competency assessment (I2).

Moreover, factors such as students' active

participation and involvement in competency-

assessing courses (I1) or the context-dependent

application of methods (I3) can complicate

competency assessment. In general, courses must be

legally secured per examination regulations (I2, I3).

Therefore, such challenges in the application of

competency-assessing methods and instruments must

be considered by instructors when using the

systematization. Fundamentally, for the successful

selection of suitable methods and instruments from

the developed systematization, the procedure

depicted in Figure 4 should be followed.

Figure 4: Selection Process of Methods and Instruments

from the Decision Matrix.

The systematization and the resulting decision

matrix, as previously outlined in Chapter 3.3, enable

the selection of suitable methods and instruments for

capturing students' key competencies. Thus, it can be

considered a foundational element for a reference

tool. The particularity lies in explicitly selecting the

key competencies to be assessed. For an even more

specific selection, the type of deployment (written,

oral, digital, physical presence, non-presence,

observation) can be chosen, ensuring a precise

alignment of methods and instruments with the

instructional format.

5 CONCLUSION AND

LIMITATIONS

By conducting an SLR analysis and four interviews

with experts from the field, this study successfully

addressed the research questions RQ 1 - 3.

Consequently, the developed systematization can

illustrate the current state of research and the practical

perspective regarding the assessment of key

competencies using appropriate methods and

instruments. Therefore, this study contributes to the

Systematization of Competence Assessment in Higher Education: Methods and Instruments

323

design of courses aimed at competence-based

assessment. While the systematization serves as an

initial compilation for a reference work, it requires

expansion. There is potential to enhance the

systematization by supplementing listed methods and

instruments with new insights. The developed search

string represents another limitation of the study. It

should be noted that it could also be expanded to

include the term »key qualifications«, as the existing

definitional concepts do not reveal a clear and

consistent usage of terminology. It must be

considered that different approaches, as mentioned in

the introduction, often use different terms for the

concept of »key competencies« while meaning the

same thing. However, this SLR's terminology was

limited to »key« and »core competencies«.

Additional synonyms might be used in further

research.

In its current stage, the systematization presents a

catalog of all significant key competencies and

associated methods and instruments for their

assessment. It specifies these methods and

instruments regarding their formats, allowing for

more targeted selection. This overview provides

educators with inspiration for their teaching activities.

However, for further support, it should be

complemented with guidelines illustrating how to

correctly apply the methods and instruments,

including their pros and cons. This enhancement

would enable educators to make more precise and

time-efficient choices, reducing reliance on external

sources. Integrating the systematization into a digital

tool is considered advantageous for future

applications to reduce accessibility barriers.

Moreover, additional connections between individual

key competencies, methods, and instruments can be

incorporated, especially in intercultural

competencies. Although the article highlights the

relevance of the systematization through existing

literature and insights from practice, practical

validation of this approach is pending and should be

addressed in future research.

REFERENCES

Almeida, F., & Buzady, Z. (2020). Development of soft

skills competencies through the use of FLIGBY.

Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(4), 417-430.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2022.2058600

Birdman, J., Lang, D. J., & Wiek, A. (2021). Developing

key competencies in sustainability through project-

based learning in graduate sustainability programs.

International Journal of Sustainability in Higher

Education, 23(5), 1139–1157. https://doi.org/10.1108/

IJSHE-12-2020-0506

Blank, J., Bergmüller, C., & Sälze, S. (2023).

Transformationsanspruch in Forschung und Bildung.

Konzepte, Projekte, empirische Perspektiven.

Waxmann. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25656/

01:28069

Brasseur, S., Grégoire, J., Bourdu, R., & Mikolajczak, M.

(2013). The Profile of Emotional Competence (PEC):

Development and Validation of a Self-Reported

Measure that Fits Dimensions of Emotional

Competence Theory. PLoS ONE, 8(5). https://doi.

org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062635

Bray, A., Byrne, P., & O’Kelly, M. (2020). A Short

Instrument for Measuring Students’ Confidence with

‘Key Skills’’ (SICKS): Development, Validation and

Initial Results.’ Thinking Skills and Creativity, 37.

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TSC.2020.100700

Caratozzolo, P., Rodriguez-Ruiz, J., & Alvarez-Delgado,

A. (2022). Natural Language Processing for Learning

Assessment in STEM. IEEE Global Engineering

Education Conference, EDUCON, 2022-March, 1549–

1554. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON52537.2022.

9766717

Cerezo, R., Bogardin, A., & Romero, C. (2019). Process

mining for self‑regulated learning assessment in

e‑learning. Journal of Computing in Higher Education,

32, 74-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12528-019-09225-

Y

Chur, D. (2002). (Aus-) Bildungsqualität verbessern. Das

Heidelberger Modell. DUZ Das Unabhängige

Hochschulmagazin, 58(3), I–IV.

Dresing, T., & Pehl, T. (2018). Praxisbuch Interview,

Transkription und Analyse - Anleitungen und

Regelsysteme für qualitativ Forschende (8th ed.).

Galuske, M. (2013). Methoden der Sozialen Arbeit - Eine

Einführung (10th ed.). Beltz Juventa.

Geißler, K. A., & Hege, M. (2007). Konzepte

sozialpädagogischen Handelns: Ein Leitfaden für

soziale Berufe (Edition Sozial) (10th ed.). Beltz Verlag.

Hain, K. (2019). Kompetenzen und Fähigkeiten - Der

Unterschied. Haysworld. https://www.haysworld.de/

arbeitswelt-karriere/kompetenzen-und-faehigkeiten-de

r-unterschied

Heymann, P., Bastiaens, E., Jansen, A., van Rosmalen, P.,

& Beausaert, S. (2022). A conceptual model of

students’ reflective practice for the development of

employability competences, supported by an online

learning platform. Education and Training, 64(3), 380–

397. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2021-0161

Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for Performing

Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/1353-7776

Kleinsorgen, C., Steinberg, E., Dömötör, R., Piano, J. Z.,

Rugelj, J., Mandoki, M., & Radin, L. (2021). “The

SOFTVETS competence model” - a preliminary project

report. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 38(3).

https://doi.org/10.3205/ZMA001446

Krüger, H. (1988). Organisation und extra-funktionale

Qualifikationen - eine organisationssoziologische und

organisationstheoretische Konzeption mit empirischen

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

324

Befunden zur Bestimmung ihres inhaltlichen

Zusammenhangs. Peter Lang Verlag.

Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2022). Qualitative

Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis,

Computerunterstützung (5th ed.). Beltz Juventa.

Lucas, M., Bem-haja, P., Santos, S., Figueiredo, H.,

Ferreira Dias, M., & Amorim, M. (2022). Digital

proficiency: Sorting real gaps from myths among

higher education students. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 53(6), 1885–1914.

https://doi.org/10.1111/BJET.13220

Martzoukou, K., Fulton, C., Kostagiolas, P., & Lavranos,

C. (2020). A study of Higher Education students’ self-

perceived digital competences for learning and

everyday life online participation. Journal of

documentation, 76(6), 1413-1458. https://doi.org/

10.1108/JD-03-2020-0041

Mertens, D. (1991). Schlüsselqualifikationen. Thesen zur

Schulung für eine moderne Gesellschaft. In F. . Buttler

& L. Reyher (Eds.), Wirtschaft- Arbeit- Beruf-

Bildung- Dieter Mertens: Schriften und Vorträge 1968-

1987 (pp. 559–572). Institut für Arbeitsmarkt und

Berufsforschung der Bundesanstalt für Arbeit.

Misoch, S. (2015). Qualitative Interviews. De Gruyter

Oldenbourg. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110354614

Mrohs, L., Hess, M., Lindner, K., Schlüter, J., & Overhage,

S. (2023). Digitalisierung in der Hochschullehre:

Perspektiven und Gestaltungsoptionen.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20378/irb-59190

Mugabushaka, A.-M. (2004). Schlüsselqualifikationen im

Hochschulbereich - Eine diskursanalytische

Untersuchung der Modelle, Kontexte und Dimensionen

in Deutschland und Großbritannien. Universität Kassel.

Münch, D. (2001). Der ideale Jungmanager oder: was

Hochschulabsolventen draufhaben sollten. Personal:

Zeitschrift Für Human Resource Management, 53(1),

29–31.

Okoli, C., & Schabram, K. (2010). A Guide to Conducting

a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems

Research. https://doi.org/Okoli, Chitu and Schabram,

Kira, A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature

Review of Information Systems Research (May 5,

2010). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/

abstract=1954824 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/

ssrn.1954824

Orth, H. (1999). Schlüsselqualifikationen an deutschen

Hochschulen. Luchterhand.

Pavlasek, P., Hargas, L., Koniar, D., Simonova, A.,

Pavlaskova, V., Spanik, P., Urica, T., & Prandova, A.

(2020). Flexible engineering educational concept:

Insight into students’ competences growth in creativity,

activity, cooperation. 13th International Conference

ELEKTRO 2020, ELEKTRO 2020 - Proceedings,

2020-May. https://doi.org/10.1109/ELEKTRO49696.

2020.9130196

Porsch, R., & Reintjes, C. (2023). Digitale Bildung im

Lehramtsstudium während der Corona-Pandemie.

Waxmann.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31244/978

3830996941

Rajesh, K., Sivapragasam, C., & Rajendran, S. (2021).

Teaching Solar and Wind Energy Conversion Course

For Engineering Students: A Novel Approach.

International Conference of Advance Computing and

Innovative Technologies in Engineering, Greater

Noida, India, 826-831.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACITE51222.2021.9404589

Saas, H. (2023). Kompetenzorientiertere Lehr-

Lerngestaltung. In Videobasierte Lehr-Lernformate zur

Erfassung und Förderung professioneller Kompetenzen

im Studium der Wirtschaftspädagogik (pp. 1–9).

Springer VS. /https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-

41320-0_1

Soeiro, A. (2018). CALOHEE: Learning outcomes and

assessment in civil engineering. 3rd International

Conference of the Portuguese Society for Engineering

Education, CISPEE 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/

CISPEE.2018.8593498

Squarzoni, A., & Soeiro, A. (2018). TUNING Guidelines

and Reference Points for the Design and Delivery of

Degree Programmes in Civil Engineering. University of

Groningen. CALOHEE Project 2018.

https://www.calohee.eu

Stanley, S., & Bhuvaneswari, G. M. (2016). Reflective

ability, empathy, and emotional intelligence in

undergraduate social work students: a cross-sectional

study from India. Social Work Education, 35(5), 560–

575. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2016.1172563

Van Helden, G., Van Der Werf, V., Saunders-Smits, G. N.,

& Specht, M. M. (2023). The Use of Digital Peer

Assessment in Higher Education-An Umbrella Review

of Literature. IEEE Access, 11, 22948–22960.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3252914

Wagenaar, R. (2019). Tuning-CALOHEE Assessment

Reference Frameworks for Civil Engineering, Teacher

Education, History, Nursing, Physics. International

Tuning Academy Groningen.CALOHEE Project 2018.

https://www.calohee.eu

Weinert, F. E. (2001). Vergleichende Leistungsmessung in

Schulen – eine umstrittene Selbstverständlichkeit. In F.

E. Weinert (Ed.), Leistungsmessungen an Schulen (pp.

17–31). Beltz Juventa.

Welbers, U. (1997). Studienstrukturreform auf

Fachbereichsebene: Vom institutionellen

Phasenmodell zum integrativen Qualifikationsmodell.

Strukturbildung gelingenden Lehrens und Lernens in

Hochschulstudiengängen und die Vermittlung

fachlicher Grundlagen am Beispiel der Germa. In U.

Welbers (Ed.), Das Integrierte Handlungskonzept

Studienreform. Aktionsformen für die Verbesserung

der Lehre an Hochschulen. (pp. 147–173).

Luchterhand.

Williams, J. C., Ireland, T., Warman, S., Cake, M. A.,

Dymock, D., Fowler, E., & Baillie, S. (2019).

Instruments to measure the ability to self‐reflect: A

systematic review of evidence from workplace and

educational settings including health care. Eur J Dent

Educ, 23(4), 389-404. https://doi.org/

10.1111/eje.12445

Systematization of Competence Assessment in Higher Education: Methods and Instruments

325

Yang, T. C., Chen, S. Y., & Chen, M. C. (2016). An

Investigation of a Two-Tier Test Strategy in a

University Calculus Course: Causes versus

Consequences. IEEE Transactions on Learning

Technologies, 9(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.

1109/TLT.2015.2510003

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

326