Outside the Box: Exploring Determinants for Participation in a Digitally

Enhanced Remote Museum Visit for Older Adults

Caterina Maidhof

1 a

, Martina Ziefle

1 b

and Andreas Sackl

2 c

1

Chair of Communication Science, RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57, Aachen, Germany

2

AIT Austrian Institute of Technology, Gieffinggasse 2, Vienna, Austria

fl

Keywords:

Older Adults, Well-Being, Social Inclusion, Cultural Inclusion, Remote Museum.

Abstract:

Cultural activities bear well-being benefits that are suitable for older adults who have an increased need to

socialize and remain active. With an exploratory qualitative approach, the study aimed to investigate partic-

ipants‘ behavioural intention to attend a remote, digitally enhanced cultural event, which involves both the

appreciation of art and social exchange. Opinions of 18 participants (age range: 60- 86) from four Euro-

pean countries (Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain) were assessed through semi-structured interviews. The paper

presents deductive themes based on the theory of planned behaviour as well as emerged inductive themes

which comprise general recommendations for such an event. The findings highlight a positive perception and

strong behavioural intention for participating in a cultural event like this, offering insights for museum orga-

nizations and designers, and emphasizing the importance of user-friendly technology and inclusive design.

1 INTRODUCTION

Older adults could benefit considerably from well-

being aspects of cultural activities as these events

leverage widespread age-related issues such as later-

life depression and loneliness while promoting cog-

nitive stimulation (Cloosterman et al., 2013; Pinquart

and Sorensen, 2001). The significant rise in the global

population of people over 60 highlights the need for

tailored activities for older adults, who typically have

more free time and an increased interest in interac-

tive activities (WHO, 2022; James et al., 2011). Un-

derstanding the diverse interests and requirements of

older adults is crucial for designing effective cultural

programs, as their needs differ from those of younger

generations (Chatterjee and Noble, 2016).

2 BACKGROUND

According to the motivational theory of lifespan de-

velopment ”successful ageing” is defined as the max-

imization of control over a variety of life domains and

for an extended period - despite constraints such as

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0573-4498

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6105-4729

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4157-5252

age-related cognitive and physical limitations (Schulz

and Heckhausen, 1996; Heckhausen et al., 2010).

In older age, maximizing control shifts from physi-

cal action to positive attitude and motivation. This

compensates for progressive declines in various skills,

enabling focus on meaningful and reachable goals

(Heckhausen, 1997; Heckhausen, 2005).

In addressing cultural opportunities for the el-

derly, physical, biological and social constraints

should be minimized and opportunities for creating

positive attitudes and emotions should be focused on.

In this way, older adults’ abilities are strengthened

and may help them cope with life challenges.

The explicit motivations of older adults to partic-

ipate in cultural activities are multiple as reflected by

the variety of museum programs tailored to older au-

diences. As part of a review museum program modal-

ities offered for older generations are classified into

reminiscence, object-oriented, art, storytelling and

lectures with reminiscence as the most common pro-

gram. These reminiscence activities sometimes hap-

pened directly in a care home and involved a discus-

sion of personal memories, occasionally with loaned

boxes of museum objects (Smiraglia, 2016). Among

the reported outcomes of these programs were mood

improvement, increased socialization, enhanced cog-

nitive functioning and improved well-being (Smi-

raglia, 2016).

152

Maidhof, C., Ziefle, M. and Sackl, A.

Outside the Box: Exploring Determinants for Participation in a Digitally Enhanced Remote Museum Visit for Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0012594900003699

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2024), pages 152-160

ISBN: 978-989-758-700-9; ISSN: 2184-4984

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Similar to reminiscence programs, (Todd et al.,

2017) researched social prescribing interventions and

determined specific elements and processes involved

in creating a social and physical environment that

stimulates the psychological well-being of older

adults. These major components are (1) the museum

as an enabler of new and positive experiences cre-

ating an outgoing and encouraging environment, (2)

the individuals on a personal journey connecting to

something within themselves and experiencing emo-

tions, (3) relational processes of judging other partic-

ipants and their behaviour which creates mutual in-

fluences (Todd et al., 2017). As there is still little

research about it, for future investigations, the au-

thors (Todd et al., 2017) advise considering individ-

ual life stories, characteristics and experiences of at-

tachment and loss as well as how these factors in-

fluence aspects of the cultural program development.

Another study on designing participatory digital cul-

tural activities for older adults carried out during the

COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of

establishing joining conditions that foster familiarity,

trust, and comfort. Tailoring events to participants’

preferences while maintaining flexible and adaptable

safe spaces turned out to be another crucial aspect

(Kist, 2021). In fact, despite the reported positive

outcomes of such social and cultural interventions, it

remains challenging to animate people so that they

‘open themselves up’ during a cultural group activ-

ity. Thus, from a user-centered perspective thoughtful

and well-reflected program development is required

to sensitively adhere to variations of human differ-

ences (Camic and Chatterjee, 2013).

This sensitivity in developing programs is even

more important when programs are digitally en-

hanced as it becomes challenging to create a trust-

ful and friendly environment where intimate topics

can be treated safely. Nonetheless, digitally enhanced

cultural offers are needed for older adults with mobil-

ity issues or for the ones living far from cultural sites

(Hilton et al., 2019).

The perceptions of cultural offers may also depend

on the cultural origin of the attending older adults

as one determinant of human aesthetic processing

and aesthetic appreciation concerns culture and social

pressures (Jacobsen, 2010). Studies suggested a re-

lation between aesthetic preferences and the concept

of context and communication (Hall, 1976; Hall and

Hall, 1990). More specifically, individuals in low-

context cultures like Germany are shown to exhibit

less personal contact and need detailed and explicit

communication. Formal information is commonly

conveyed directly, often through written texts. In

contrast, individuals in high-context cultures such as

Spain or Italy maintain closer and more familiar con-

tact, preferring informal and indirect modes of com-

munication. Related to remote museum visits these

cultural differences need to be taken into account, as

well-toned social interaction is essential, and events

may involve museums from various countries, poten-

tially needing adaptation to local cultural contexts.

2.1 State of the Art

In sum, cultural programs for older adults emerge

as a trend to combine healthcare with cultural ex-

periences, particularly through reminiscence and so-

cial prescription programs aimed at supporting psy-

chological well-being. These increasingly digital-

supported programs foster personal reflection on sen-

sitive life experiences, ultimately strengthening a

sense of belonging. Careful planning and further re-

search are necessary to ensure a comfortable environ-

ment for these experiences. This paper aims to in-

vestigate older adults’ motivations for potential atten-

dance at a digitally enhanced remote museum visit

which focuses on reflections and discussions about

personal life.

A suitable theoretical framework is the theory of

planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) with its objective

to predict and understand human behaviour including

technology acceptance (e.g., (Venkatesh et al., 2003)).

Behavioural intention is a core concept of the theory

and defined as an “indication of a person´s readiness

to perform a given behaviour” (Ajzen, 1991). Here,

the given behaviour is attendance at the previously

described cultural event. According to theory, the

behavioural intention is the most important predic-

tor of the actual behaviour and is dependent on the

unfolding of (1) attitude (i.e., either positive or nega-

tive evaluations of the behaviour), (2) subjective norm

(i.e., subjective normative pressures from others re-

garding the behaviour) as well as (3) the perceived

behavioural control (i.e., degree to which a person be-

liefs being able to perform a given behaviour). An

overall goal in the context of the study would be

comfortable attendance in cultural experiences, ide-

ally benefitting well-being.

2.1.1 Research Question

Given these theoretical arguments and underpinnings,

the following research question has emerged:

• What are the determinants and influences con-

tributing to the behavioural intention to participate

in a remote museum visit?

Outside the Box: Exploring Determinants for Participation in a Digitally Enhanced Remote Museum Visit for Older Adults

153

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

This section outlines the study’s empirical approach.

It covers the characteristics of semi-structured inter-

views and their data analysis, describes the interview

guidelines and procedure, including the example of an

inclusive cultural experience, and presents the charac-

teristics of the study participants.

3.1 Semi-Structured Interviews and

Data Analysis

The interview was developed following the guide-

lines described in (D

¨

oring and Bortz, 2016). Partic-

ipants were interviewed for about 40 - 60 minutes

(mostly) in pairs to enhance the exchange of opin-

ions (Flick et al., 2000). The interviews were audio-

taped and transcribed verbatim. The theoretical basis

of the qualitative analysis was the thematic qualita-

tive text analysis described by (Kuckartz, 2014). This

comprised the usage of pre-defined deductive themes

based on the interview questions as the first step of the

analysis and subsequent inductive analysis of the text

to identify emerging themes. As part of the assess-

ment of demographics and measures of well-being,

items were rated on a six-point Likert scale (e.g.,

”Over past two weeks I felt comfortable”, 1 = never to

6 = always).

3.2 Interview Procedure

Before starting the interview participants were given

a short screening questionnaire which started with the

agreement to the data protection. The questionnaire

contained questions regarding demographics, health

conditions, assessments of loneliness (Hughes et al.,

2004) and mental well-being (Tennant et al., 2007).

Afterwards, participants were welcomed with a gen-

eral introduction to the topic. Subsequently, the ex-

ample of an inclusive cultural experience with pic-

tures and a video clip of the procedure of the event

was shown (see section 3.2.1). After this presenta-

tion participants were asked about their impression of

such an event and were encouraged to name positive

and negative aspects likewise. Then questions regard-

ing behavioural control about the course of the event

and participants’ perceptions of how such events are

received by the general population (i.e., subjective

norm) were posed. Other aspects regarding partic-

ipants’ perceptions of control and well-being dur-

ing such an event were posed after an interactive

part which will not be further reported at this point.

Conditions for comfortableness were assessed which

included participants’ preferences with whom they

would like to share such an event and whether the con-

versations could be registered. As a last question, the

behavioural intention to attend such an event was as-

sessed including participants’ willingness to pay for

it. The interview finished with an informal talk.

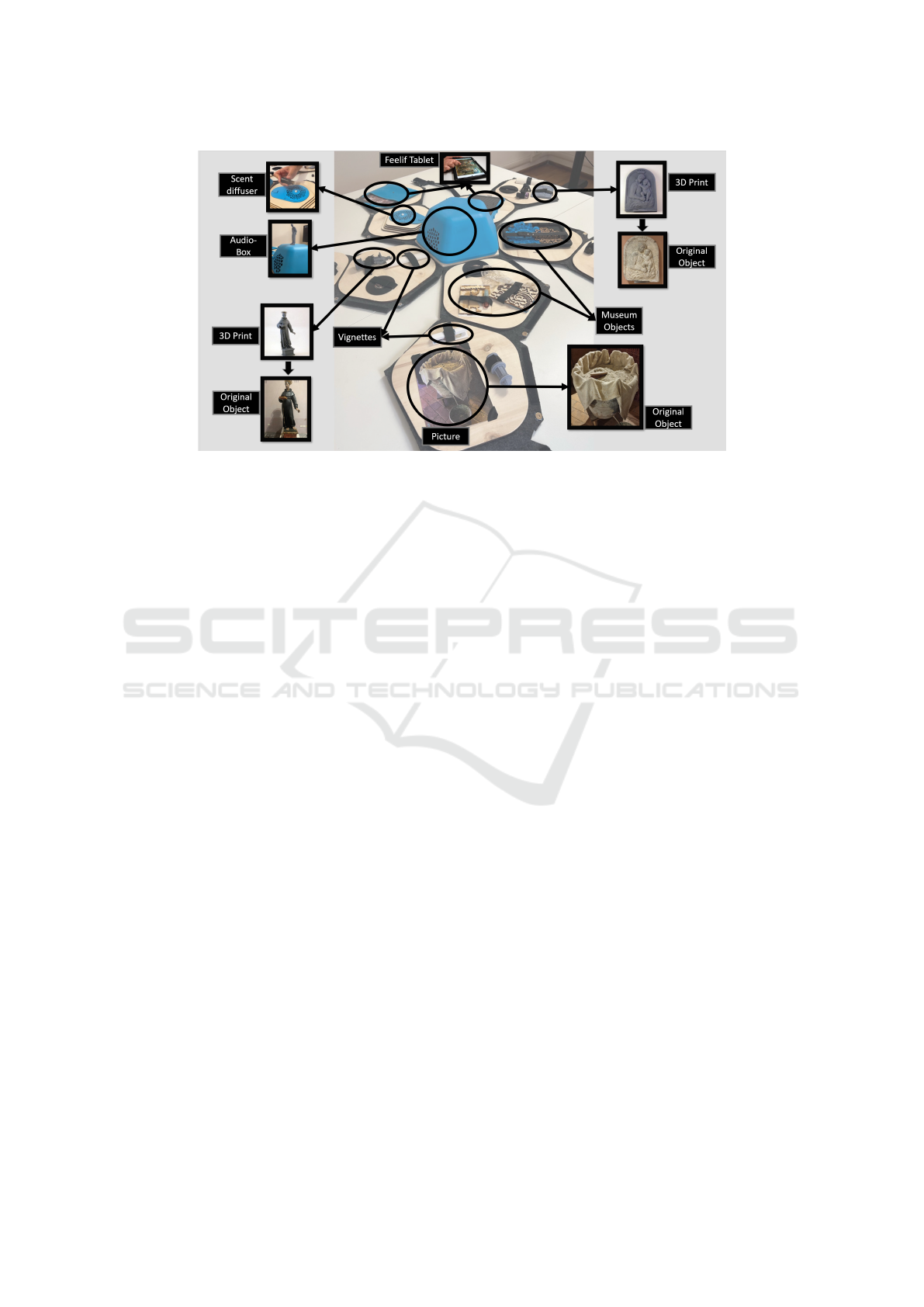

3.2.1 Example of Cultural Experience

The European Project (BeauCoup, 2021) aims to cre-

ate ways for older adults to better explore and interact

with cultural heritage. Within this project, cultural ex-

perience is reached with the support of multi-sensory

and inclusive technologies making use of digital and

analogue tools. For this study, the prototype called

”The Box” was used as a reference (see Figure 1),

more information and the video shown to participants

can be found on the project website. The box was

explained with this description:

Attendees of the event gather at a table with moderators

leading. The moderators welcome everyone and initiate an

icebreaker game for introductions. Subsequently, the art-

themed ”The Box” is introduced, containing multi-sensory

objects (e.g., 3D prints, pictures, portable museum objects,

a tablet app (Regal et al., 2023) and attendees are encour-

aged to explore it. As a second important part of the event

and to promote exchange and social interaction among the

individual attendees, the moderators ask the attendees to

share their feelings and their own experiences on a topic

related to the content of the box. Care is taken that each

attendee has the same opportunity to share something from

their own life leading to discussions guided and concluded

by the moderators.

3.3 Participants

The qualitative study was carried out in autumn 2023

with semi-standardized interviews either in person or

through video calls. The volunteering participants

were over the age of 60, interested in cultural ac-

tivities and were recruited from the private and pro-

fessional networks of the researchers. As the Beau-

Coup Project operates on a European scale, it was

not only possible but also reasonable to gather per-

spectives from participants coming from diverse Eu-

ropean countries. Recognizing that appreciation and

social interaction with art are influenced by cultural

contexts, the decision was made to include viewpoints

from Austria (n=4), Germany (n=5), Italy (n=4), and

Spain (n=5).

Participants’ age ranged from 60 to 86 (N=18,

M=70.31, SD=8.44, two persons did not disclose ex-

act age) with slightly more females (n=11, 61.1%)

than males (n=7, 38.9%). When asked for partici-

pants’ highest educational degree, 11.1% (n=2) in-

dicated not having any educational degree, 16.7%

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

154

Figure 1: Exemplary Box used to explain the concept.

(n=3) indicated having a primary or secondary degree,

11.1% (n=2) indicated having a high school diploma

and 55.6% (n=10) stated having obtained a university

degree (One abstained). Participants assessed them-

selves as feeling well health-wise (M=5.06, SD=0.64)

with only 33.1% (n = 6) suffering from a chronic

illness (i.e., rheum, cognitive decline, cardiac ar-

rhythmia). Some mentioned their disabilities which

were visual impairment (n=4) and hearing impair-

ment (n=2). Participants specified not being lonely

(3 items, M=1.53, SD=0.72, α =.88) and psychologi-

cally well (14 items, M=4.25, SD=0.49, α =.92). Half

of the participants (n=9, 50%) pointed out having pri-

vate and/or professional care experience.

4 RESULTS

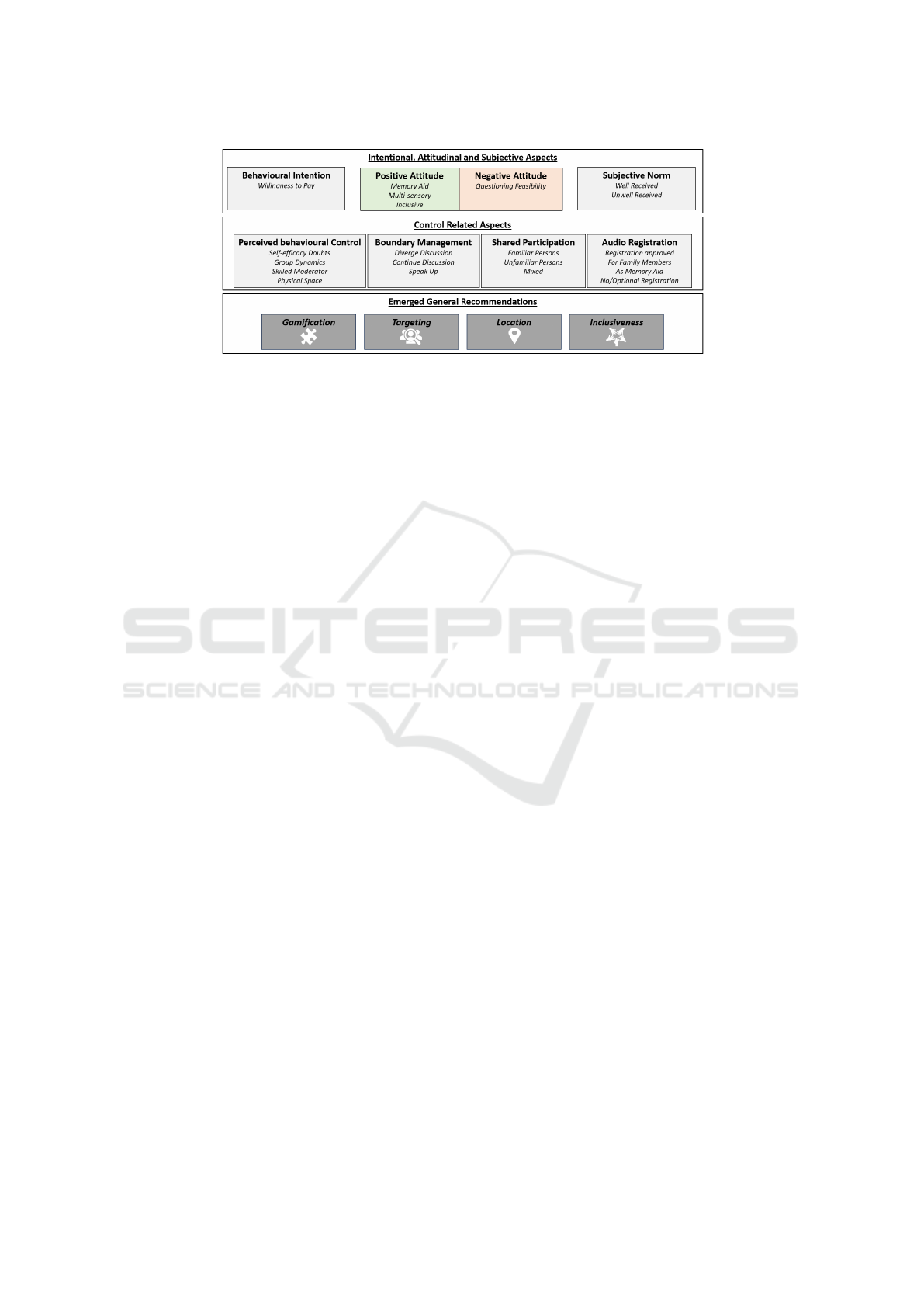

Results from the thematic analysis were grouped into

three major topics ”Intentional, Subjective and At-

titudinal Aspects”, ”Control Related Aspects” and

”Emerged general Recommendations” and further di-

vided into several major deductive categories from

which several inductive subcategories emerged (see

Figure 2).

4.1 Intentional, Subjective and

Attitudinal Aspects

These categories relate to participants’ readiness to at-

tend the proposed event (Behavioural Intention) and

their views on existing societal opinions (Subjective

Norm). The categories further involve evaluations of

the exemplary inclusive cultural event presented dur-

ing the interview (Positive/Negative Attitude).

Behavioural Intention. Within this category partici-

pants’ readiness to visit such an event including their

willingness to pay for it is reported (Ajzen, 1991).

Overall the majority of participants (n=13) expressed

their readiness to participate stating to be ”curious”

(P7), ”excited” (P13) and gathering with other people

would be a ”source of life energy” (P13, P16). The

remaining participants (n=5) were not against partic-

ipation, however, they would only go ”depending on

the circumstances” (P6, P5) and ”if it matches my in-

terest” (P4) or ”in a couple of years” (P17, P18).

Willingness to Pay. Participants’ answers were

roughly twofold even though many agreed that the

price should be adjusted for seniors. One part of

the participants was in favour of paying for it them-

selves honoring the organizing staff and comparing

it to gymnastic classes or normal museum visits. In-

deed, one idea (P18) was to organize these types of

events as alternatives and alongside physical museum

exhibitions.

”I propose a parallel and collateral event that

somehow allows people, who would gladly attend

but can’t due to structural or mobility issues, to

benefit from the content of this exhibition.[..] In-

stead of buying a ticket to attend the exhibition in

person, you buy a ticket, and the exhibition comes

to your care home for example.” (P18)

The other participants preferred external funding es-

pecially when this event would take place outside of

a museum in a care facility (P15, P17).

Positive Attitude. This and the subsequent cate-

gory comprise participants’ first impressions but also

their elaborate evaluation when confronted with the

cultural event presented during the interview (Ajzen,

1991). Many participants had a positive impression

and mentioned more positive than negative thoughts

Outside the Box: Exploring Determinants for Participation in a Digitally Enhanced Remote Museum Visit for Older Adults

155

Figure 2: Illustration of Categories (inductive categories in italics).

on the proposed event. Participants valued it as an

”original idea” (P3, P11) and as something ”you can

enjoy while sitting comfortably at the table” (P18).

P16 specifically liked that it ”has a surprise factor”.

More concrete thoughts could be allocated into the

subsequent three categories.

Memory Aid. Four participants (P9, P10, P11, P12)

believed that expressing feelings and sharing experi-

ences through sensory stimuli, such as objects, lights,

and smells, could help older adults recall positive

memories and generate bonds with others.

Multi-Sensory. Participants appreciated the multi-

sensory set-up and thought it was especially suitable

and beneficial for people with special needs (P12,

P16).

Inclusive. Another highlight for many participants

was the inclusiveness that this event offered, not only

because of the multi-sensory design. They saw it as

both, a way to connect people and a possibility for

personal creative expression, independent from health

status or disability. The box in the middle of the table

was seen as a large support.

”A big box [..] is an added value to create a great

sense of community. You encourage people through

such things to give something from themselves and

it´s a good exchange. You learn a lot from others

[..] and maybe you can combine that with your own

experience. It can help you. When you see that

others have had similar experiences.” (P3)

Negative Attitude. Rather than purely negative com-

ments, participants mentioned the following doubts.

Questioning Feasibility. This regarded doubts about

how to reach participants who are very withdrawn and

are not a member of any organisation (P3) and doubts

about how to manage logistics and the transport of

older adults with motor difficulties (P17).

Subjective Norm. This category summarizes par-

ticipants’ normative beliefs which means how they

believe their peers and society at large would think

about such an event (Ajzen, 1991). Mostly, partici-

pants estimated that the larger society including peo-

ple they know personally would appreciate such an

event. Only a few mentioned some doubts providing

reasons why such an event might not be successful.

Therefore, the answers could be grouped into two dis-

tinct subcategories.

Well Received. Participants thought that such an event

would capture the interest of a larger public including

that it would have the potential to receive positive me-

dia attention (e.g., P15) as an age-friendly event for

everybody.

”Everyone can take part, not just people who have

some kind of deficit. And that’s why it’s inclusive.

That’s what it’s supposed to be, isn’t it? It doesn’t

marginalize people.” (P5)

Unwell Received. Participants expressed the diffi-

culty of connecting with elderly individuals, espe-

cially the ones living in a care home. They were scep-

tical that the ones that are isolated could be reached

through traditional methods such as announcements.

One participant (P3) even suggested a medical order

in these cases.

4.2 Control Related Aspects

The categories that are part of this topic relate to

internal and external factors that participants would

consider as either facilitating or hindering atten-

dance at the proposed cultural event. This includes

participants’ subjective assessments of whether and

how these factors are controllable (Perceived Be-

havioural Control, Boundary Management) and

their preferences regarding Shared Participation and

Audio Registration.

Perceived Behavioural Control. This category deals

with answers regarding the ease or difficulty with

which participants would estimate to be able to partic-

ipate in such an event (Ajzen, 1991). Generally, par-

ticipants believed to be able to maintain a level of con-

trol over themselves and the situation, even when fac-

ing problems. However, participants also identified

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

156

several factors on which this ability would depend and

these are summarized into the following four subcat-

egories.

Self-Efficacy Doubts. Some participants were con-

cerned that they would not be able to deal with

the device containing the art and especially with the

technical aspects of it and therefore strongly sug-

gested a straightforward design to avoid excluding

technology-unsavvy persons.

Group Dynamics. Participants felt that their feeling

of control was dependent on the other people and the

resulting dynamics. Two participants even stated that

the maximum number should be reduced to six (P11)

or eight (P12). Besides, according to participants, the

entire group in such an event has to be motivated to

be there and somehow get along with each other.

Participants feared that only a few would draw at-

tention to themselves and hinder a harmonious flow

of the conversation.

”That has to be well managed in a way that one

person doesn’t get the upper hand and becomes the

leader of the whole troop and the others then no

longer come to share their opinion or are overrun.”

(P3)

Similarly, the content of the event was also mentioned

to play a role and participants expressed preferences

in having intellectual conversations with like-minded

people (P3, P15).

”The ideal would be that individuals are somewhat

aligned in terms of the conversational basis.[..] the

intellectual level, if I may say so, could indeed

influence or hinder the dynamics of the group or

somehow not favour them, especially if very differ-

ent people participate in this event.” (P15)

Skilled Moderator. Participants oftentimes high-

lighted the importance of a skilled moderator to mit-

igate unbalanced group dynamics and steer the con-

versation which requires preparation.

”Moderators have to find out beforehand what kind

of people we have here at the table, and what

deficits they may have so that they can respond well

to them. And depending on that, they have to mod-

erate more or take a step back.” (P5)

Another requirement was the responsiveness of the

moderator during the event, in terms of facial expres-

sion, emotional availability and management of dy-

namics. Participants honored this work a lot and one

participant (P5) even recommended that two people

would lead the event. One participant (P2) compared

the work of the moderator to the one from a psychol-

ogist.

Physical Space. The location was important for par-

ticipants to feel at ease with the event. Indeed, partic-

ipants said that the room where the event would take

place had to be comfortable, pleasurable and tailored

to older adults‘ needs.

”First of all, the environment should be [..] a bit

cosy. For people of a certain age, it shouldn’t be

noisy or particularly loud, with no people passing

by or leaving to avoid distractions.” (P18)

”The colours of the room, chairs with armrests,

overall the furniture should be comfortable.” (P17)

Boundary Management. This category includes par-

ticipants‘ strategies mentioned for dealing with mo-

ments of discomfort when topics and feelings come

up that cross their boundaries. The strategies that par-

ticipants reported seem to be rooted in different core

beliefs and underlying values and can therefore be

grouped into three distinct subcategories.

Diverge Discussion. When confronted with an un-

wanted topic, several participants preferred respond-

ing vaguely or redirecting the conversation to avoid

potential conflicts. They described that this approach

would involve the use of both, verbal and non-verbal

cues.

”It’s not a strategy per se, but to get to the point

where you might see there’s a conflict I would try to

mediate, calm down, relax, using words, even non-

verbal language, like to steer away from this and

if not, it’s better to step back or change the entire

subject, whatever works.” (P12)

Continue Discussion. Another part of participants

would prefer to continue the discussion, despite un-

comfortable feelings and confrontations. As rea-

sons participants named idealistic motives grounded

in personal values and standards.

”Once you’ve started, it’s also good to continue.

You have to continue; you can’t say no. You know

it will touch you more, but you’ll try to make it

through, I don’t know, with some change in atti-

tudes, words, saying things lighter.” (P2)

”I want to value my opinion as well. Because be-

fore, I would not say anything and let it pass, but

even if it’s a bit late I’m learning to say what I

think.” (P16)

Speak Up. Other participants expressed their pref-

erences for addressing the uncomfortable feeling di-

rectly by verbally telling the others with clear verbal

signals of unwillingness to go any further with the

topic (e.g., P13, P7).

Shared Participation. This category involves par-

ticipants‘ preferences with whom they would like to

share such an event from which three subcategories

emerged.

Familiar Persons. Some participants chose to enjoy

the experience with friends and family. They regarded

this event as a leisure activity, aiming for a fun and

comfortable (P4) atmosphere with a natural flow.

Outside the Box: Exploring Determinants for Participation in a Digitally Enhanced Remote Museum Visit for Older Adults

157

”Older people are more cautious about making

new friends, they’re not as open, right? [..] Easier

among people who know each other, in my opinion,

more natural than among people who have no rela-

tionships, who have never seen each other.” (P18)

Unfamiliar Persons. Contrarily, other participants

preferred events with unfamiliar people for positive

surprises, excitement, and mutual enrichment. They

view these encounters as opportunities for gaining di-

verse perspectives, new ideas, and reflection on as-

pects of life not apparent within familiar circles.

”With people you know, you already discuss your

views on different things, but with people you don’t

know, it’s great to open up and discuss things. I

don’t think I’m right about everything, it’s impor-

tant to reflect on things that maybe you hadn’t real-

ized in your life.” (P16)

Mixed. Certain participants opted for a version that

included both familiar and unfamiliar individuals, be-

lieving that this choice would enhance the overall di-

versity and make the mix more intriguing (P7, P12).

Audio Registration. In this category participants‘

thoughts on registering the conversations of the event

through audio registering are gathered and divided

into four subcategories.

Registration Approved. One part of the participants

did not question the purpose of registering or the later

use of the material but agreed upon it right away, say-

ing for instance, it is ”not a big deal.” (P13).

For Family Members. Some participants agreed to

register the conversations during the event with the

restriction of using it as a memory piece for fam-

ily members. One participant (P12) even suggested

not only registering the audio but also recording a

short video of the event which could be appreciated

by both, the family members and the ones attending.

”So that the grandchildren, when they are older,

can hear what Grandpa said or what he told about

himself from the past. Then I find it like in an al-

bum, right? In that context, it could be offered, but

otherwise, I don’t think it’s good.” (P5)

As Memory Aid. Especially among the participants

over the age of 70, registration as a personal memory

aid was welcomed, considered useful and even impor-

tant. They drew comparisons to photography and saw

it as a way to conserve the experience.

No/Optional Registration. The remaining partici-

pants did not like the audio registration and were not

convinced by the various purposes and objectives of

the registration. Despite disagreeing with the regis-

tration, two participants (P15, P17) eventually did not

want to reject the option entirely and proposed either a

professional recording aligned with an exhibition or a

retelling of a salient moment upon consensual agree-

ment for registration.

4.3 Emerged General

Recommendations

Throughout the entire interview process, several rec-

ommendations inductively emerged. These results are

summarized in Table 1.

5 DISCUSSION

The paper presented a qualitative exploration of older

adults’ behavioural intention to attend a remote and

digitally enhanced cultural event that is composed of

both, the exploration of art and the social exchange

among fellows. Participants responded positively to

the event, showing keen interest and curiosity. While

feasibility was questioned, there were no direct nega-

tive reactions to the idea. Overall, there was a strong

intention to participate, highlighting a clear demand

for similar cultural offerings.

In line with the literature (e.g., (Chatterjee and

Noble, 2016)), the proposed event in the study was

considered as supporting well-being, creative expres-

sion and cognitive stimulation such as memory train-

ing. Particularly, the multi-sensory experience was

considered a great driver for inclusiveness providing

means for persons with disabilities to participate and

express themselves by being able to fall back on their

functioning senses. This attempt to reduce constraints

can be seen as ultimate support for developing control

strategies for successful ageing (Schulz and Heck-

hausen, 1996).

Results identified three key elements: organiz-

ers, participants, and relational processes, as in (Todd

et al., 2017). The event moderator’s role was cru-

cial, requiring both soft and hard skills to manage dy-

namics and respond empathetically, especially to un-

expected situations. Participants felt comfortable in

their role and believed they could maintain control,

expressing readiness to manage discomfort (e.g., not

speaking about a certain topic) if necessary. Over-

all, participants didn’t express strong concerns, possi-

bly due to their characteristics that favour perceptions

of control such as feeling healthy, rather independent

and not lonely. Relational processes were empha-

sized, focusing on harmonious interactions without

dominance.

Some cultural differences could be observed in

line with previous cross-cultural findings (Hall and

Hall, 1990; Hall, 1976). More in detail, partic-

ipants living in Spain, a country tending towards

collectivism and high-context (more familiar con-

tact, informal and indirect modes of communication)

strongly highlighted the suitability of the event for

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

158

Table 1: Emerged Recommendations.

Category Description

Gamification Create curiosity and fascination with playful elements (e.g., games, quizzes) that can be explored.

Use interactive features where individuals continuously open or uncover things.

For paintings, use puzzles to assemble angles or use brushes and oil colours.

Targeting Tailor experiences based on interests (e.g., natural sciences, sculptures, etc.),

considering the influence of the setting (museum vs. care home).

In care homes there is more focus on socialization, in museums more on multi-sensory experience.

Location Choose a convenient location accessible by public transport.

Consider hosting events outside care home settings so that older adults can enjoy a change of scenery.

Inclusiveness Consider it as an event to strengthen family bonds across generations

using objects as mediators for relationships and memories.

Provide technology learning opportunities with user-friendly interfaces. Ensure accessibility for

individuals with age-related sensory impairments (e.g., appropriate text contrast, font size,

and audio device suitability for individuals with age-related hearing loss (presbycusis)).

families, friends and intergenerational exchange. Per-

haps somewhat related were the preferences of par-

ticipants from Austria, a country where individual-

ism and low-context communication (less personal

contact, detailed, explicit and formal communication)

prevail. Interestingly, Austrian participants in specific

valued intellectually engaging conversations, ideally

grounded in a shared conversational basis. It is note-

worthy that Austrians almost exclusively and inde-

pendently from each other mentioned their preference

regarding an explicit and rather formal type of con-

versation whereas Spanish participants referred to op-

portunities for strengthening ties within families and

peers. Combined with participants’ assumption that

socialization can be more emphasized in care homes

compared to external settings in the museum, a tenta-

tive prediction would be that starting to organize these

kinds of events within care homes might be more suc-

cessful in Spain whereas such a cultural experience

happening in the museum itself would resonate more

successfully with an Austrian or German public.

Overall, the findings can guide museum organiza-

tions and technical designers in developing remote se-

tups. Design considerations should prioritize straight-

forward technology and playful elements that stimu-

late personal conversations so that not all the social

stimulations are initiated by the moderator. Addi-

tionally, ensuring an appealing and inclusive physical

space for each target user group is essential. Based on

participant responses, collaboration with care facili-

ties is recommended to understand specific needs and

coordinate logistics for attendees from care homes.

5.1 Limitations and Future Work

The current work presents some limitations which

should be addressed in future investigations. The

present qualitative assessment was based on a ver-

bal description and pictures and videos of the event.

Neither ”The Box”, a prototype itself nor the event

was experienced directly by the participants. As the

study was exploratory the descriptions of the event

did not refer to a specific topic (e.g., rural life in the

past century, paintings dealing with mental disorders)

and therefore overall left a lot to the imagination.

While all these aspects helped explore the diversity

of opinions, future work should study pre - and post-

assessments of an actual event to attain more specific

insights. More concretely, for example, wizard-of-oz

experiments could be conducted with technical de-

vices such as the tablet or audio box to increase us-

ability. Further, gamification of the experience was

considered important for participants. The question

of how to implement these playful elements within

the time and resource frame of such an event for peo-

ple with disabilities remains open and needs to be in-

vestigated through, for instance, focus groups with

those affected. Another future research focus should

regard audio registration as a memory aid, specifically

mentioned by participants over 70. Longitudinal case

studies of actual participants could be one approach

to conceptualize an adequate design for such memory

pieces.

The study was conducted in four European coun-

tries which contributed to a more representative sam-

ple overall but cultural differences could only be

looked at superficially because only a few individu-

als were interviewed per country. This has to do with

the exploratory qualitative method, not allowing any

generalisation and the fact that the sample was not en-

tirely homogeneous. Nonetheless, different tenden-

cies could be observed in answers from participants

from different countries. These are in line with cul-

tural differences on the country level and emphasise

the importance of contextually targeting these cul-

tural events. However, these tendencies should not

Outside the Box: Exploring Determinants for Participation in a Digitally Enhanced Remote Museum Visit for Older Adults

159

be overrated here, instead, future research should use

a more homogeneous and larger sample per country

for a more informative cross-cultural comparison.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper provided a cross-European qualitative ex-

ploration of older adults’ behavioural intention to en-

gage in a remote, digitally enhanced cultural event

that combined art exploration and social exchange.

The findings offer practical guidance for developing

such events tailored to the preferences and require-

ments of older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is funded by the BeauCoup Project, which

has received funding from AAL Joint Programme un-

der grant agreement No AAL-2021-8-156-CP, and the

Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme

under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement

No 861091 for the visuAAL project.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Or-

ganizational behavior and human decision processes,

50(2):179–211.

BeauCoup (2021). Beaucoup. Accessed on 06.June, 2023.

Camic, P. M. and Chatterjee, H. J. (2013). Museums and

art galleries as partners for public health interventions.

Perspectives in public health, 133(1):66–71.

Chatterjee, H. and Noble, G. (2016). Museums, health and

well-being. Routledge.

Cloosterman, N. H., Laan, A. J., and Van Alphen, B. P.

(2013). Characteristics of psychotherapeutic integra-

tion for depression in older adults: A delphi study.

Clinical gerontologist, 36(5):395–410.

D

¨

oring, N. and Bortz, J. (2016). Forschungsmethoden und

evaluation. Wiesbaden: Springerverlag.

Flick, U., Kardorff, E. v., and Steinke, I. (2000). Qualitative

forschung. Rohwolt.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Anchor.

Hall, E. T. and Hall, M. R. (1990). Understanding cul-

tural differences: Germans, French and Americans.

Yarmouth: Intercultural Press.

Heckhausen, J. (1997). Developmental regulation across

adulthood: primary and secondary control of age-

related challenges. Developmental psychology,

33(1):176.

Heckhausen, J. (2005). Competence and motivation in

adulthood and old age. Handbook of competence and

motivation, pages 240–256.

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., and Schulz, R. (2010). A moti-

vational theory of life-span development. Psychologi-

cal review, 117(1):32.

Hilton, D., Levine, A., and Zanetis, J. (2019). Don’t lose

the connection: Virtual visits for older adults. J. of

Museum Education, 44(3):253–263.

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo,

J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness

in large surveys: Results from two population-based

studies. Research on aging, 26(6):655–672.

Jacobsen, T. (2010). Beauty and the brain: culture, history

and individual differences in aesthetic appreciation. J.

of anatomy, 216(2):184–191.

James, B. D., Wilson, R. S., Barnes, L. L., and Bennett,

D. A. (2011). Late-life social activity and cognitive

decline in old age. J. of the Int. Neuropsychological

Society, 17(6):998–1005.

Kist, C. (2021). Repairing online spaces for “safe” outreach

with older adults. Museums & Social Issues, 15(1-

2):98–112.

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative Text Analysis A Guide to

Methods, Practice Using Software. SAGE Publica-

tions.

Pinquart, M. and Sorensen, S. (2001). Influences on loneli-

ness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and appl.

social psychology, 23(4):245–266.

Regal, G., Maidhof, C., Puthenkalam, J., Khermayer, v.,

Pav

ˇ

sek, K., and Sackl, A. (2023). Feel the art: Digital,

tangible postcards for accessible cultural experiences.

In Proc, of the 22nd Int. Conf. on Mobile and Ubiqui-

tous Multimedia, MUM ’23, page 559–561.

Schulz, R. and Heckhausen, J. (1996). A life span model of

successful aging. American psychologist, 51(7):702.

Smiraglia, C. (2016). Targeted museum programs for older

adults: A research and program review. Curator: The

Museum Journal, 59(1):39–54.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph,

S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., and Stewart-

Brown, S. (2007). The warwick-edinburgh mental

well-being scale (wemwbs): development and uk val-

idation. Health and Quality of life Outcomes, 5(1):1–

13.

Todd, C., Camic, P. M., Lockyer, B., Thomson, L. J., and

Chatterjee, H. J. (2017). Museum-based programs

for socially isolated older adults: Understanding what

works. Health & Place, 48:47–55.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D.

(2003). User acceptance of information technology:

Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3):425–

478.

WHO (2022). Ageing and health. Accessed on 06.June,

2023.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

160