Guiding the Adoption of UX Research Practices: An Approach to

Support Software Professionals

Maria Anita de Moura

a

, Su

´

ellen Martinelli

b

and Luciana Zaina

c

Federal University of S

˜

ao Carlos (UFSCar), Sorocaba, S

˜

ao Paulo, Brazil

Keywords:

User Experience, UX, UX Research, UX Methods, Software Professionals, Empirical Study.

Abstract:

The interest in User Experience (UX) with interactive products and services has grown in the industry. In this

context, the research with end-users contributes to articulating practices, methods, and research techniques

on UX that can be applied at different stages of software development. Nevertheless, software development

professionals have demanded tools that can aid them in selecting the suitable method or technique for a given

purpose of user research. To address this demand, we developed guidelines that suggest methods and tech-

niques for working with user experience research. Considering the guidelines, we created the GURiP tool

in the virtual catalog format, providing a more dynamic interaction with the guidelines. We evaluated the

proposal acceptance with 32 software professionals from software startups and established companies. Our

results revealed that professionals of both types of companies showed similar acceptance and reported more

positive than negative feedback about the guidelines. We also found that participants’ profiles, such as years

of experience or affiliation with startups or established companies, did not influence the acceptance of the

guidelines.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been a significant increase

in recognition of challenges associated with integrat-

ing the design of user experience (UX) into software

development (Silveira et al., 2021; Hokkanen and

V

¨

a

¨

an

¨

anen-Vainio-Mattila, 2015; Kashfi et al., 2019).

There are different definitions of UX in the literature;

however, the majority of them include both the soft-

ware’s functionalities and its quality characteristics as

elements perceived by end-users during their inter-

actions (Hassenzahl, 2018). Software professionals

(e.g., developers, UX designers, and UX researchers)

have faced obstacles to incorporating UX into devel-

opment processes, such as a lack of knowledge in

UX and limited availability of resources (Kashfi et al.,

2019; Silveira et al., 2021). Besides, studies indicate

that the adoption of UX practices is fundamental in all

stages of software development (Silveira et al., 2021;

Hokkanen and V

¨

a

¨

an

¨

anen-Vainio-Mattila, 2015).

From different UX design disciplines, UX Re-

search emerges as essential to sustain the product

conception and evolution (Farrell, 2017). UX Re-

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-4886-8217

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4421-2940

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1736-544X

search systematically researches and evaluates users’

interaction with a product by providing techniques

and methods to collect, analyze, and interpret user

data (Farrell, 2017; Pazitka, 2019). Practices for this

purpose generate meaningful insights on UX design,

which contribute to decision-making about product

development from users’ motivations and pains (Paz-

itka, 2019). Thus, UX Research practices (i.e., UXR

practices) represent recurring attitudes, actions, or

activities of user experience research and evaluation

work, which satisfy user-centered product develop-

ment (Meingast et al., 2013). UX Research work

is relevant to reducing the risk of failure in product

development (S

¨

uner-Pla-Cerd

`

a et al., 2021), besides

bringing significant value and establishing a competi-

tive edge for the company (Silveira et al., 2021).

Despite the variety of UX methods and tech-

niques, there is a lack of solutions to facilitate the se-

lection of UX Research methods and techniques most

suitable for the needs of companies and their product

development objectives (Hokkanen and V

¨

a

¨

an

¨

anen-

Vainio-Mattila, 2015). Professionals can easily find

a description of practices dedicated to data collection

and analysis in UX (S

¨

uner-Pla-Cerd

`

a et al., 2021);

however, there is still a lack of knowledge among pro-

fessionals about how to analyze user feedback (Sil-

de Moura, M., Martinelli, S. and Zaina, L.

Guiding the Adoption of UX Research Practices: An Approach to Support Software Professionals.

DOI: 10.5220/0012597100003690

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024) - Volume 2, pages 473-484

ISBN: 978-989-758-692-7; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

473

veira et al., 2021). Besides, professionals struggle

in how to transform user data into useful information

for software development (Hokkanen and V

¨

a

¨

an

¨

anen-

Vainio-Mattila, 2015).

From the gap of tools that support the application

of UX Research into practice, a set of 14 guidelines

was proposed. These guidelines assist software pro-

fessionals in their UX Research work by suggesting

UXR practices, methods, and techniques to conduct

research and evaluation with users. These guidelines

were conceived from a Systematic Literature Review

(SLR) that analyzed 45 studies conducted in the soft-

ware industry. Considering the findings of the SLR,

we developed an online catalog Guidelines for UX

Research in Practice (GURiP) to provide a useful and

accessible resource for professionals looking for ad-

vice on how to implement UX Research in practice.

We evaluated the acceptance of the guidelines in

the dimensions of perceived ease of use, usefulness,

and intent to use, as well as the participants’ over-

all feedback. Our study involved 32 professionals

who were instructed to apply the GURiP tool’s guide-

lines in practical UX Research scenarios. The group

of participants comprised a diverse range of profiles,

including UX and software professionals in different

positions in software startups and established compa-

nies. We considered it relevant to have startup and

established company professionals in our sample due

to the literature suggesting that startup professionals

generally have a shorter tenure of professional ex-

perience. Our findings indicate that the guidelines

were well-received and emphasized that they could

be useful mainly for novice professionals. Our re-

sults also showed that participants’ professional back-

grounds did not significantly impact the guidelines’

acceptance, demonstrating their suitability across var-

ious profiles.

This paper is organized as follows. The related

work and the conception of the guidelines are pre-

sented in Sections 2 and 3, respectively. Section

4 gives all the procedures adopted in the guidelines

evaluation. The findings are presented in Section 5

and the discussion of the findings and the their re-

lation with the literature in Section 6. Finally, the

contributions and the conclusions are pointed out in

Section 7.

2 RELATED WORK

A survey involving 65 organizations in Saudi Ara-

bia examined professionals’ perceptions of UX and

related practices, focusing on obstacles impeding the

integration of UX work in software development envi-

ronments (Majrashi and Al-Wabil, 2018). The results

indicated that participants identified the primary ob-

stacle as a lack of understanding or knowledge about

UX Research, exacerbated by a shortage of trained

UX professionals. Another survey in Saudi Arabia

gathered responses from 75 software professionals

(Alhadreti, 2020). The study aimed to assess the per-

ception of professionals about the significance of UX

in software development and the challenges in UX

work. The findings showed that task analysis, proto-

typing, and heuristic evaluation are methods prevalent

during various stages of product development, espe-

cially in the prototyping phase.

A previous study also discussed the main chal-

lenges of integrating UX and agile methods in soft-

ware development (Meingast et al., 2013). Among

the findings, the significance of collaborative activ-

ities, such as brainstorming sessions and informa-

tion sketching, along with the involvement of stake-

holders and developers in UX activities, was high-

lighted. In another study, the authors categorized or-

ganizational barriers from a systematic literature re-

view (Kervyn de Meerendr

´

e et al., 2019). These

barriers encompass the inadequacy of UXR practices

and methods, insufficient UX literacy, and subopti-

mal utilization of UX artifacts. The study highlights a

prevalent lack of comprehension among profession-

als regarding UX, often compounded by confusion

between UX and User Interface (UI). This misunder-

standing, in turn, contributes to hindering the appli-

cation of UX Research methods and artifacts within

organizational contexts.

A recent study presented a UX Process Refer-

ence Model (UXPRM), which includes delineating

fundamental UX lifecycle processes and systemati-

cally classifying UX methods and artifacts (Kieffer

et al., 2019). UXPRM furnishes a comprehensive

overview of UX-centric practices that encompass col-

lecting data on opinions, feedback, and user behav-

ior. Methods for knowledge elicitation are further cat-

egorized into those involving user participation and

those without, the latter focusing on predicting sys-

tem usage through expert opinions. In a SLR, the

authors highlighted the need for specialized UX re-

search technologies prioritizing user-friendliness and

comfort (Rivero and Conte, 2017). The results argue

that future UX evaluation technologies should inte-

grate diverse aspects and prevent duplication or con-

fusion between quantitative and qualitative data from

achieving comprehensive evaluation reports.

In addition to these studies, researchers proposed

a tool to recommend UX evaluation methods by em-

ploying filters that conducted the stakeholders dur-

ing evaluations (Oliveira et al., 2023). The feasi-

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

474

bility study gathered positive feedback from partici-

pants about the perception of the usefulness of tools

that suggest UX methods to help professionals in the

decision of which practice or method they should

adopt. Besides, the feedback revealed the need for

tools for centralized ease of access to UX-related con-

tent guides.

Our guidelines differ from the related work above

by focusing on a specific UX area, i.e., UX research.

The guidelines were elaborated considering a SLR,

a similar approach adopted by (Rivero and Conte,

2017), incorporating UXR practices widely employed

in the industry.

3 UX RESEARCH PRACTICES’

GUIDELINES

Our guidelines aim to assist software professionals in

working with UXR practices. In particular, we in-

tend to support professionals in employing UXR prac-

tices in industry settings. The guidelines related to

UXR practices are categorized into six groups (see

Table 1 for group descriptions). Fourteen guidelines

were derived from the literature, as outlined in Table

2. Each guideline includes details about the methods

and techniques suggested, practical guidance to apply

them, and the professionals who should be involved

in putting the guideline into practice. Each guideline

clearly defines its objectives and outlines the associ-

ated benefits of the proposed methods and tools.

The guidelines were elaborated by following a rig-

orous Systematic Literature Review (SLR) method

(Kitchenham and Charters, 2007). The entire process

of guideline construction is detailed in our previous

work (Martinelli et al., 2022). In this paper, we will

briefly describe the construction process; further de-

tails will be added in case the paper is accepted.

The search string was applied to five scientific pa-

per’s search engines (i.e., ACM Digital Library, Engi-

neering Village, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, and Web of Sci-

ence) and resulted in 634 papers selected. Our exclu-

sion criteria focused on eliminating papers published

before 2001, short papers, or studies that showed

technical problems of software (e.g., algorithm opti-

mization, programming). Meanwhile, our inclusion

criteria are dedicated to selecting papers that describe

UXR practices applied by the software industry, as

well as papers that present contributions to UX Re-

search work (e.g., how has been applied user research,

collection, analysis, or interpretation of data).

After applying the inclusion and exclusion crite-

ria, 45 papers were deemed relevant to our analysis.

We thus conducted a qualitative analysis using open

Table 1: Groups of UXR Practices.

Research Planning (RP)

Actions focused on planning activities in UX Research,

encompassing the definition of research goals, organization

of research tasks within software development teams,

and the creation of artifacts or prototypes to facilitate

research conduct.

Research Training (RT)

Actions to encourage a culture of research and user evaluation

among software industry professionals, including training

in UX research skills.

Collecting Data with Users (CD)

Actions dedicated to generating data through research

and user testing, conducted at different stages of the

software development cycle.

Data Analysis (DA)

Actions that aid decision-making in software development

through quantitative and qualitative analysis methods.

Organization and Communications (OC)

These communicative actions involve organizing and

communicating with professionals in software development.

They are related to research and evaluations conducted by

these professionals.

Design with Research (DR)

Approaches that integrate UX Research into the UX Design

process, with a special focus on creating the initial design,

involving the development of software prototypes.

These designs and prototypes serve as support for

conducting user research activities.

code, a technique in which the names and meanings of

the codes emerge from the analyzed data itself (Gibbs,

2018). The researcher assigns codes and definitions to

each set of extractions based on the common meaning

of these extractions (Charmaz, 2006). As a result, we

identified 38 UXR practices that were applied by the

software industry.

These practices were further categorized into six

groups (see Table 1) based on essential actions or at-

titudes dedicated to UX Research work, e.g., defin-

ing research goals, collecting user feedback, apply-

ing user tests, and developing research skills. Conse-

quently, we developed a set of guidelines that can help

professionals choose the best UXR practices, meth-

ods, and techniques to facilitate data collection and

evaluation at different stages of the product lifecycle.

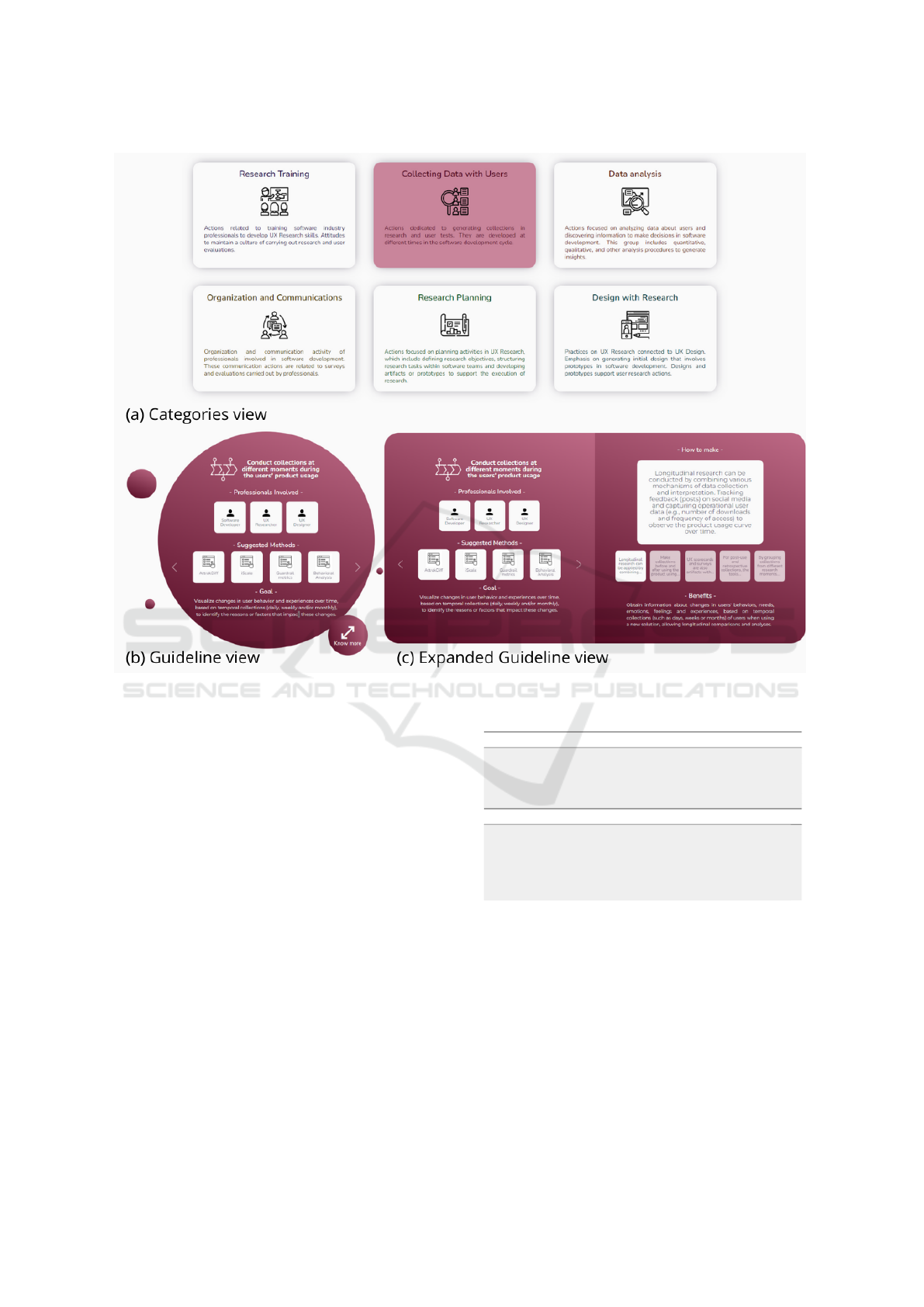

Considering the guidelines, we have developed

the GURiP tool, building upon our formulated guide-

lines and their respective categories (see Figure 1).

This tool is specifically tailored for professionals in

the software industry, with a primary objective of fa-

cilitating the finding of new techniques and meth-

ods of UX Research suitable for each stage of prod-

uct development. The GURiP tool

1

offers three dis-

tinct views: one provides an overview of general cat-

egories, another shows the details of the guidelines

within each specific group, and a final view offers

more in-depth information about individual guide-

1

GURiP tool available in http://uxleris.net/gurip/.

Guiding the Adoption of UX Research Practices: An Approach to Support Software Professionals

475

Table 2: Guidelines for UX Research in Practice (GURiP).

Research Planning (RP)

RP1

Defining goals, strategies, and pre-established

roles related to the practical work of UX

Research.

RP2

Planning user research and evaluations,

considering the support of artifacts to aid in this

planning.

Research Training (RT)

RT1

Conducting workshops, training sessions, and

internal study groups on UX Research among

professionals involved in different teams.

RT2

Establishing partnerships with academic experts

in UX/UCD or with agile and UCD consultants

to conduct workshops or training sessions on

UX Research.

RT3

Implementing strategies to guide on the

importance of UX at the business level and

promote the UX Research practices carried out

internally by professionals involved in different

teams.

Collecting Data with Users (CD)

CD1

Conducting collections that combine different

moments of product use by users (before,

during, and after use) to generate longitudinal

UX research.

CD2

Generating initial and anticipatory user research

before the product development cycle.

CD3

Frequent and continuous user testing and

evaluations at any stage of product

development.

Data Analysis (DA)

DA1

Developing user data analyses to generate

valuable insights for product development.

DA2

Frequently analyzing operational and system

data derived from user interactions with

products and services.

DA3

Conducting qualitative analyses of user

interaction with the product and

cross-referencing results with quantitative data.

Organization and Communications (OC)

OC1

Adapting research and evaluation activities with

users according to project needs and available

resources.

OC2

Creating lean artifacts or actions to share

knowledge about users.

Design with Research (DR)

DR1

Developing designs integrated with UX

Research practices and guided by UX

information.

lines.

The GURiP tool’s catalog presents categories with

titles, icons, and descriptions on cards (see Figure

1(a)). By selecting a category, the user can access the

category page containing the guidelines. Users can

access all the essential information for each guideline,

including the title, objective, recommended methods

and techniques, and the professionals involved (see

Figure 1(b)). The methods suggested are shown as

hyperlinks to external pages with more in-depth de-

tails. We provide the option to obtain additional in-

formation about each guideline, provide instructions

on how to implement it, and highlight its usage ben-

efits (see Figure 1(c)). The tool is available on the

Internet; however, we could not provide its link due

to the double-blind review policies.

4 EVALUATION

Our study followed the guidelines for experimen-

tal studies (Wohlin et al., 2012). Our study was

approved by the ethics committee of the Federal

University of S

˜

ao Carlos under the process number

68524023.0.0000.5504.

The study was conducted by two researchers,

hereafter referred to as R1 and R2. R1 is an under-

graduate student in Computer Science and currently

plays the role of web developer as an intern at a com-

pany; R2 is a Ph.D. candidate in Computer Science

with 6+ years of experience in User Experience and

qualitative research.

4.1 Planning

Participants were invited to take part in the study

voluntarily through announcements disseminated via

LinkedIn. Our invitation included posts in profes-

sional groups related to UX Research, UX Design,

and software development. Additionally, we sent

emails to contacts within our professional network.

The selection of participants was based on conve-

nience and availability to participate in the study

(Wohlin et al., 2012). Both professionals from star-

tups and established companies were invited to join.

The participants were divided into two groups: one

consisted of software startup professionals, and the

other composed of software professionals from estab-

lished companies.

We designed the study to explore two scenarios

using guidelines through the GURiP tool. Within the

tool, users were free to navigate through guideline

groups and subsequently, within each group, access

the available guidelines in each category. In each sce-

nario, participants had the flexibility to select one or

more guidelines that best suited the proposed situa-

tion.

An online questionnaire was developed to collect

data on participants’ professional profiles (e.g., years

of experience, market segment of the company, and

role in the company). The questionnaire included the

Informed Consent Form to obtain participants’ agree-

ment to be part of the study. We also created an on-

line feedback questionnaire based on the Technology

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

476

Figure 1: GURiP Tool.

Acceptance Model 3 (TAM3) (Venkatesh and Bala,

2008), an updated version of the Technology Accep-

tance Model (Davis, 1989) to gather participants’ per-

ceptions of the guidelines. We utilized TAM3, which

presents questions divided into three constructs. The

perceived usefulness construct represents how much

a person believes using a specific technology can en-

hance their performance in UX-related tasks. The

ease of use construct is related to the perception that

the technology can be adopted effortlessly. The third

construct concerns the user’s intention to use the tech-

nology (Dias et al., 2011). We added three open-

ended questions at the end of each construct.

Finally, we wrote up two scenarios that depict how

users would interact with the guidelines. The scenar-

ios aimed to assess practical aspects such as the ap-

plication’s ease of use, utility perception, and users’

comprehension of categorizing guideline groups (see

Table 3).

We had a senior researcher with 20+ years of ex-

perience in empirical studies in industry and User Ex-

perience research evaluate our study. They reviewed

and refined the profile questionnaire and other arti-

Table 3: Scenarios.

Scenary 1

“You need to gather feedback from users about a new

feature implemented. Afterward, you need to materialize

this feedback through an electronic presentation to share

the results with the team.”

Scenary 2

“You need to identify patterns in the data regarding the

difficulties and needs of users after the release of the

latest update. You’ve never done this type of activity

before and decided to seek assistance in conducting

this inspection.”

facts. In addition, a professional with eight years of

experience in software development and UX design

participated in our pilot test. This professional helped

us understand what hindered their understanding of

the scenarios, which allowed us to improve the clarity

and accuracy of the scenarios. After these changes,

we concluded that no further alterations were neces-

sary, and the study could proceed.

Guiding the Adoption of UX Research Practices: An Approach to Support Software Professionals

477

4.2 Execution

The study involved 32 professionals who worked in

different companies in Brazil. Of these professionals,

16 were employed in startups and 16 in established

companies. The research was conducted through on-

line meetings using the Google Meet platform

2

. R1

and R2 followed the same script to ensure the unbias

of the study execution with each session having an

average duration of 30 minutes.

The researchers welcomed the participants in each

session and briefly outlined the study’s objectives.

Participants agreed to the informed consent terms for

using their data and recording the meeting for aca-

demic purposes, and they completed the profile ques-

tionnaire. The participants engaged in a warm-up

exercise to familiarize themselves with GURiP tool.

Participants could freely navigate the tool to level

their knowledge of the catalog. The warm-up lasted

approximately 5 minutes for each participant.

Once the warm-up was completed, we presented

the different scenarios to the participants. Each par-

ticipant’s proposed solutions were expressed verbally

using the think-aloud method, in which participants

speak aloud any words in their mind as they complete

a task (Charters, 2003). The participants’ screens and

audio were recorded with their permission while uti-

lizing the tool. Based on the participants’ responses or

speeches, we collected information on which guide-

lines each professional would use to solve the given

scenarios. After the guidelines usage, participants

could provide comments or opinions about using the

guidelines. Finally, participants were invited to re-

spond to the TAM online questionnaire (Dias et al.,

2011).

4.3 Analysis

We considered three sources for data analysis. We

conducted a qualitative analysis by considering the

feedback responses from open-ended TAM questions

and the comments made by participants at the end of

the scenario implementations. For the quantitative

analysis, we utilized the responses to closed-ended

questions from the online questionnaire. R1 and R2

were responsible for the data analysis. Besides, a se-

nior researcher with 20+ years of experience in empir-

ical studies in industry and User Experience research

supervised and discussed all results with R1 and R2.

The qualitative analysis followed three steps.

First, we utilized closed coding, which involves iden-

tifying text excerpts and categorizing them within a

2

https://meet.google.com/.

pre-established codebook (Corbin, 1998). This tech-

nique helped us to explore all responses more thor-

oughly. Our research involved using a codebook that

included three codes to represent the dimensions of

TAM (Dias et al., 2011), as well as three codes to

identify different professional experiences: those with

less than 3 years of experience, those with between 3

and 5 years of experience, and those with more than 5

years of experience. We classified participants’ feed-

back using two codes: ‘positive feedback’ and ‘nega-

tive feedback’. Additionally, we assigned open codes

to the excerpts. We applied open codes as a sec-

ond technique to allow the researcher to identify new

codes from the analyzed data (Gibbs, 2018). This

technique enables the assignment codes and their def-

initions from a common meaning of the grouped ex-

tractions (Charmaz, 2006). We code what the emerg-

ing topics are concerning positive and negative feed-

back. The R1 developed open codes during data anal-

ysis, which were later validated and refined by R2.

Finally, we explored participants’ acceptance re-

sponses regarding using guidelines in the dimensions

of perceived of usefulness, perceived of ease-of-use,

and intention to use use using the objective questions

from the TAM questionnaire (Table 4). In the ques-

tionnaire, participants responded on a 4-point Likert

scale. We applied a scale without a neutral point to

favor a more accurate response and prevent the par-

ticipant’s choice of a neutral point, avoiding a conflict

of opinion with the researcher (Garland, 1991; Johns,

2005). We also analyzed whether their profiles influ-

enced technique acceptance.

Table 4: TAM Questions.

Construct ID Question

Perceived

of

Ease-of-use

E1

I find the guidelines easy to understand.

E2

I consider that interacting with the

guidelines demands minimal mental

effort.

E3

I find it easy to apply the guidelines.

E4

I find that using the guidelines makes my

work easier.

Perceived

of

Usefulness

U1

Using the guidelines helped me in

performing UX Research activities.

U2

Using the guidelines made it easier to

perform UX Research activities.

U3

Using the guidelines improved my

performance in UX Research tasks.

U4

I consider the guidelines useful for

performing UX Research tasks.

Perceived

of future

use intent

F1

Given access to the guidelines, I plan to

utilize them.

F2

Given access to the guidelines, I foresee

using it.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

478

4.4 Threats to Validity

We adopted the four elements (i.e., conclusion, con-

struct, internal, and external) to discuss the threats to

validity (Wohlin et al., 2012) and outlined our strate-

gies to mitigate the study issues. To ensure the reli-

ability of our conclusions from the results, we relied

on multiple sources of data (i.e., profile questionnaire,

scenarios with verbal feedback, and TAM question-

naire that included open-ended questions), as well as

a mixed-methods approach for data analysis. Both

types of analysis were conducted by the first author

and reviewed by the other authors, who are experi-

enced in qualitative and quantitative analyses. Dur-

ing the open and closed coding activities, the first au-

thor frequently communicated with the second author,

who guided the conducting of the qualitative analysis.

To avoid problems in the construction validity, we

followed a consistent script in all study sessions and

provided the same scenarios to every participant. Fur-

thermore, we included a preliminary scenario to lever-

age participants’ previous knowledge. We also em-

phasized various guideline categories to reduce the

effects of misunderstandings of UX Research and the

guidelines as a whole.

We set a maximum duration of one hour for each

study session to evade potential participant fatigue,

which can threaten internal validity. By using the

GURiP tool, the participants employed less effort in

handling the guidelines usage. All necessary infor-

mation for implementing the scenarios was available

in the tool, including the guidelines’ objectives and

benefits.

Our study involved 32 participants from startups

and established companies, which ensured diversity

in their professional experience and roles. This ap-

proach helped us obtain a representative sample for

our research objectives, securing external validity.

5 FINDINGS

The profile of the participants is summarized in Table

5. We observed a balanced representation of profes-

sionals from both startups and established companies,

as well as various experience levels and job roles.

We will present findings in the two next sections:

guidelines acceptance and the influence of partici-

pants’ profiles on the results.

5.1 Acceptance of the Guidelines

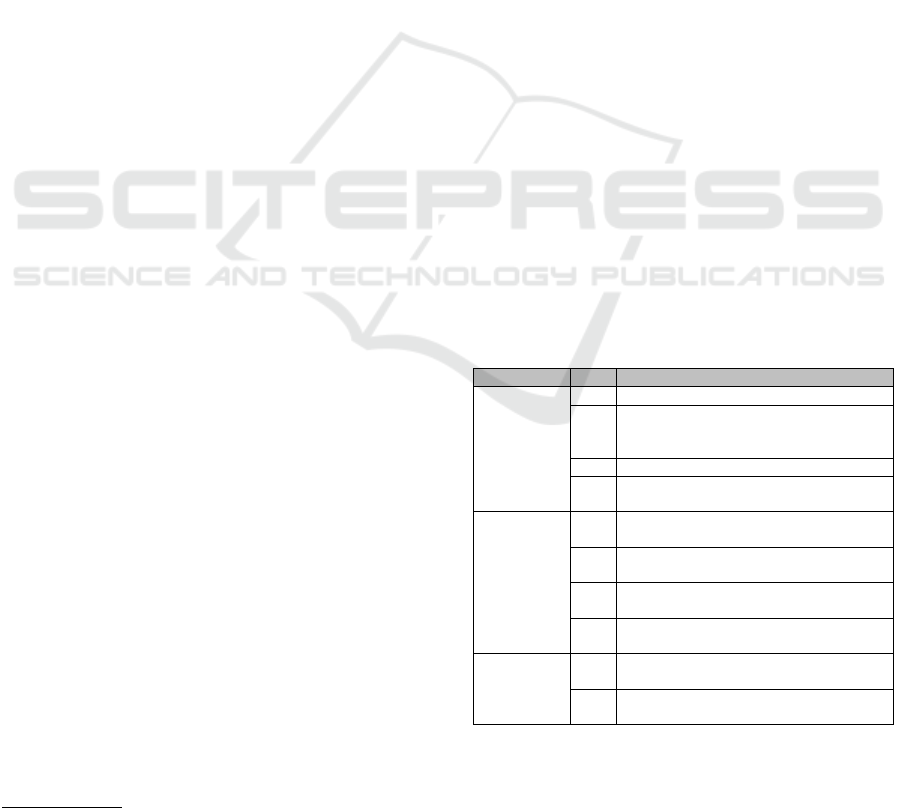

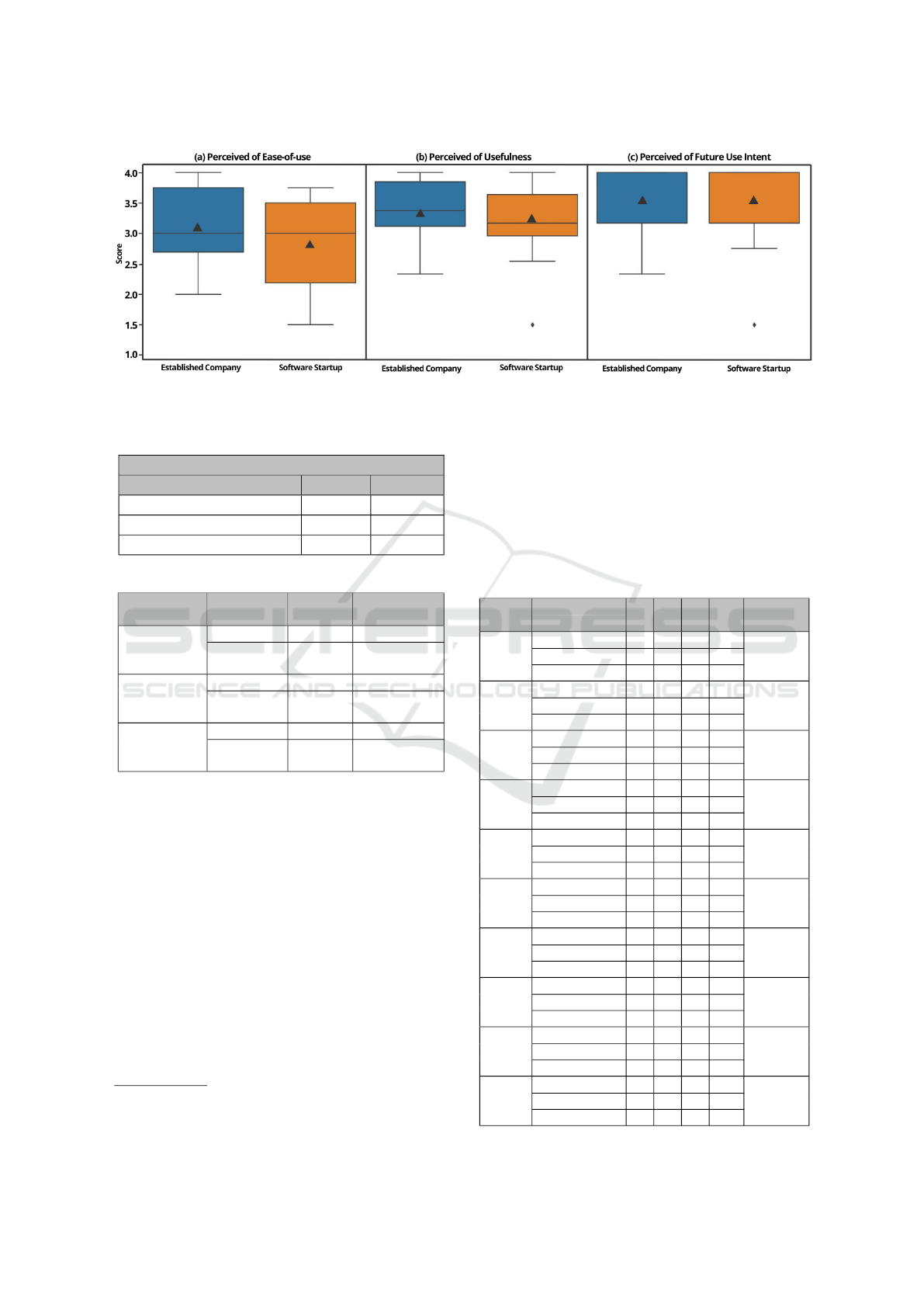

The participants’ responses are shown in Figures 2

and 3. In the figures, we see that participants from

startups and established companies highly accepted

the guidelines in general. However, a different result

can be observed in Figure 3 about the Perceived of

Usefulness dimension. By crossing the participants’

profiles with the results, we saw that Participant P04,

who works for a startup with over 5 years of expe-

rience, assigned low scores to all questions for that

construct. Unfortunately, we could not find an expla-

nation for the low scores because the participant did

not point out the reasons.

Figure 2: Acceptance results of professionals from estab-

lished companies.

Figure 3: Acceptance results of professionals from startups.

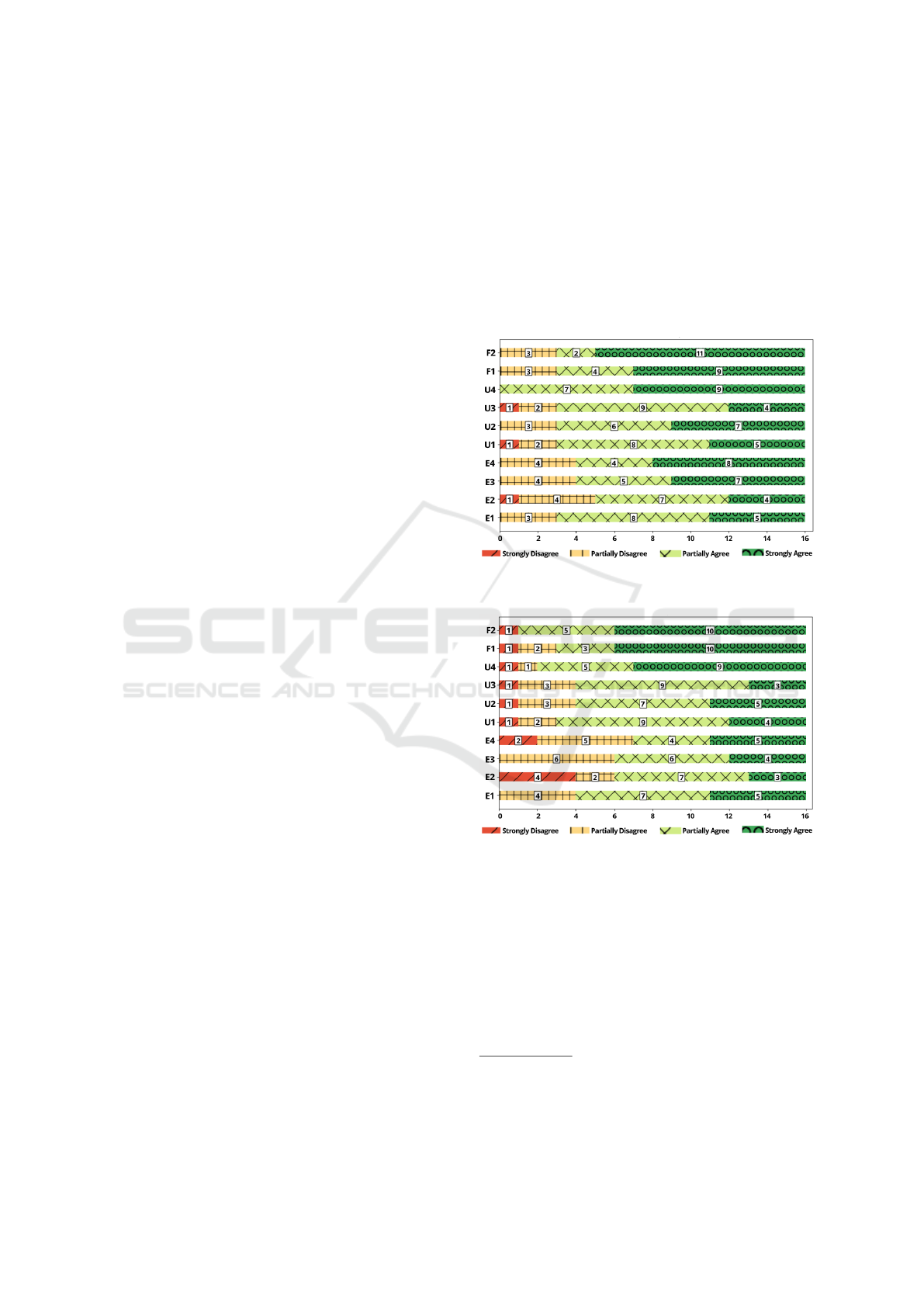

To provide a supplementary view of the TAM re-

sults, we examined the comments made by the partic-

ipants and their relationship with the TAM constructs.

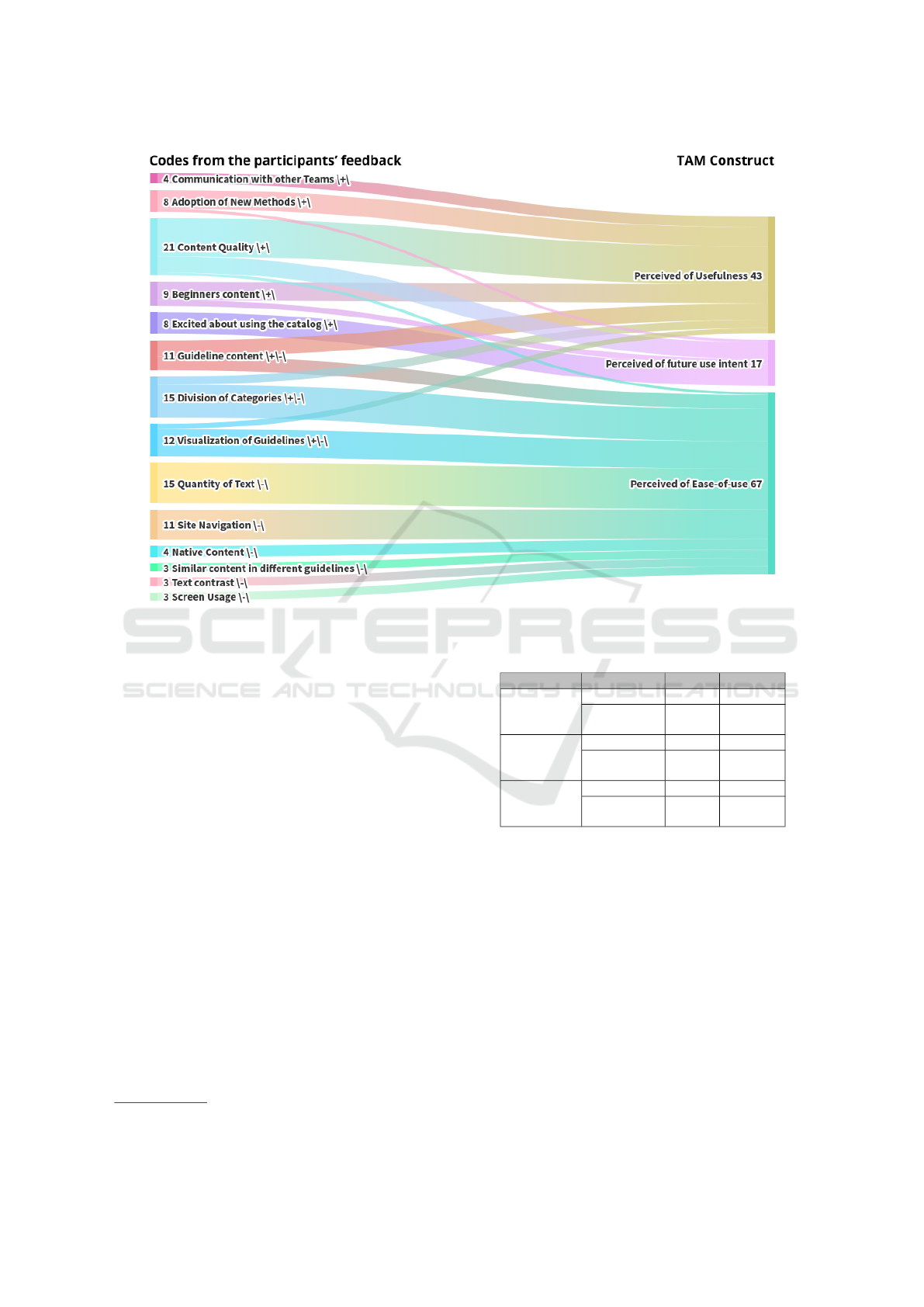

Figure 4 shows a Sankey diagram

3

that illustrates the

link of the open codes (on the left side) and their as-

sociation with the corresponding TAM construct (on

the right side). The open codes emerged in the quali-

tative analysis and expressed the positive or negative

feedback provided by the participants. In Figure 4,

3

Sankey diagram is a flow diagram in which the width

of the arrows is shown proportionally to the flow quantity.

It helps locate dominant contributions to an overall flow

(Schmidt, 2008).

Guiding the Adoption of UX Research Practices: An Approach to Support Software Professionals

479

Table 5: Participants’ profile.

Id Group* Position Experience Market segment

P01 EC UX Researcher <3 years Data and credit granting

P02 EC UX Coordinator UX <3 years Tourism / Services

P03 SS UX Researcher >5 years Venture Capital

P04 SS UX Researcher >5 years Fintech

P05 EC UX Designer, UX Researcher >5 years Product and Design Consulting

P06 SS UX Designer, UX Researcher <3 years Healthtech

P07 EC UX Designer, UX Researcher 3 to 5 years Information Technology

P08 SS Product Manager <3 years Fintech

P09 EC UX Researcher >5 years Edtech

P10 SS UX Researcher 3 to 5 years Agtech

P11 SS UX Researcher <3 years Tourism / Services

P12 EC UX Designer, UX Researcher 3 to 5 years Information Technology

P13 EC UX Researcher >5 years Fintech

P14 SS UX Researcher, Product Designer <3 years Information Technology

P15 EC Software Engineer, Tech Lead 3 to 5 years Edtech

P16 SS UX Designer 3 to 5 years HRtech

P17 SS UX Researcher >5 years Accounting

P18 SS Research Project Consultant >5 years Logistics

P19 EC UX Designer <3 years Information Technology

P20 EC UX Researcher 3 to 5 years Telecommunications

P21 SS Product Designer <3 years Information Technology

P22 SS UX Designer >5 years Information Technology

P23 SS UX Designer, UX Researcher <3 years Information Technology

P24 SS Developer <3 years Accounting

P25 SS UX Designer, UX Researcher 3 to 5 years Digital and In-person Events

P26 SS Software Engineer, UX Researcher >5 years Logistics

P27 EC Project Manager <3 years e-Commerce

P28 EC R&D Analyst <3 years R&D Consulting

P29 EC SAP Business Consultant SAP <3 years Information Technology

P30 EC Project Manager 3 to 5 years e-Commerce

P31 EC Software Developer 3 to 5 years Information Technology

P32 EC Software Engineer, Tech Lead >5 years Information Technology

*Legend: SS to Software Startup; EC to Established Company.

the width of the arrows illustrates the number of quo-

tations and helps identify each column’s main contri-

butions toward the overall flow. For each open code,

we indicate whether the feedback was positive, nega-

tive, or both by using the labels +, -, and +/- for both),

respectively. Besides, the number of the participant’s

quotations for each open code and TAM construct is

informed between brackets in the figure. By look-

ing at Figure 4, we observe that positive feedback is

mostly related to the constructs of Perceived of Use-

fulness and Intention to Use. In contrast, negative

feedback is primarily linked to the Perceived Ease-

of-use of the guidelines.

Regarding the Perceived Ease-of-Use construct,

we identified 15 instances of the label quantity of

text, predominantly associated with negative feed-

back. Participants noted that excessive details about

the content of the guidelines made it more challeng-

ing to find guidelines that were useful for each sce-

nario; it can be seen from P27 comment: ”Some long

texts make it challenging to quickly understand each

block of information.” On the other hand, the open

code division of categories emerged as a recurring

theme related to positive feedback in the Perceived

Ease-of-Use construct. It was observed that adopt-

ing categories to group the guidelines made finding

the suitable guidelines easier as expressed by P03:

”The breakdown of training, collection, analysis [cat-

egories]... feels more intuitive.”.

Considering the constructs of Perceived of Use-

fulness and Intention to Use, participants expressed a

favorable view of the guidelines’ content, particularly

emphasizing its high quality for newcomers in the UX

research area: ”The tool, I think it’s pretty cool, espe-

cially helpful for someone who’s just starting in the

career or even those who sometimes need to conduct

research without much guidance.”, commented P16.

Additionally, participants recognized the value of the

content of the guidelines as an introductory resource

for beginners and a valuable tool for seasoned profes-

sionals seeking to explore and adopt innovative meth-

ods and techniques in their work, as mentioned by

P20: ”Method visualization helps a lot when we have

complex research to conduct and end up getting stuck

in using method X or Y. This way, we can freshen up

our ideas a bit”.

5.2 Influence of Participants’ Profile in

the Results

We conducted two tests to investigate the potential in-

fluence of participants’ profiles on the results. First,

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

480

Figure 4: Relation of the participants’ feedback (open codes) and the TAM constructs.

we explored whether the fact that the professionals are

working in startups and established companies could

affect the participants’ responses about acceptance of

the guidelines. We carried out this verification be-

cause startups and established companies present dif-

ferent dynamics in their workplace and consequently,

their professionals usually have different perspectives

about the work. To conduct the verification, we com-

puted the mean and median values for each TAM con-

struct, splitting the professionals’ responses into two

groups, i.e., startups and established companies (see

Table 6 and the boxplots in Figure 5). We see a small

difference in the average when comparing the values

of startups and established companies. In particular,

by looking at Figures 2 and 3, we see a difference in

the Perceived of Usefulness, i.e., in E2 and E4 ques-

tions. The results showed that some participants con-

sidered they should employ mental efforts to use the

guidelines (i.e., E2) and also that the guidelines will

not make their work easier (i.e., E4).

We performed the Independent Samples T-Test

test

4

. This choice was based on the paired and inde-

pendent nature of the samples and the observed nor-

mal distribution. The latter was confirmed through the

Shapiro-Wilk test (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965). Shapiro-

4

https://www.statstest.com/independent-samples-t-test

Table 6: Mean and Median for each group.

Construct Group Mean Median

Perceived

of

Ease-of-use

Startup 2.8 3.0

Estabilished

Company

3.1 3.0

Perceived

of

Usefulness

Startup 3.06 3.0

Estabilished

Company

3.21 3.25

Perceived

of future

use intent

Startup 3.43 4.0

Established

Company

3.43 4.0

Wilk test was conducted at a significance level of 95%

(i.e., 0.05) to assess the distribution of samples for

each TAM construct. The results indicated that sam-

ples from established companies and startups demon-

strated a normal distribution as outlined in Table 8.

To conduct the Independent Samples T-Test, we de-

fined the null hypothesis (H0) and alternative hypoth-

esis (H1) as follows: H0 - There is no influence of

workplace type on the acceptance of the technique.,

and H1 - There is an influence of workplace type on

the acceptance of the technique. Table 7 presents the

results (see p-value) and they indicate that no signif-

icant evidence supports the idea that the fact of the

professional works in a startup or an established com-

pany influenced the acceptance of the guidelines.

After, we verified whether the participants’ expe-

Guiding the Adoption of UX Research Practices: An Approach to Support Software Professionals

481

Figure 5: The scale ranged from 1, indicating ’strongly disagree,’ to 4, representing ’strongly agree’. The median: a horizontal

line inside the ’box’; the mean: a black triangle.

Table 7: Independent Samples T-Test.

Influence of the type of company

Construct TAM t value p value

Ease-of-Use -0,894 0,379

Perceived of Usefulness -0,085 0,933

Use intent -0,096 0,924

Table 8: Shapiro test.

Construct Group p value

Normal

Distribution

Perceived

of

Ease-of-use

Startup 0.06 Yes

Stabilished

Company

0.16 Yes

Perceived

of

Usefulness

Startup 0.07 Yes

Stabilished

Company

0.14 Yes

Perceived

of future use

intent

Startup 0 No

Stabilished

Company

0 No

rience influenced their acceptance of the guidelines by

performing Fisher’s exact testing

5

. We divided the

participants into three groups based on their experi-

ence level: <3 years, 3 to 5 years, and >5 years. The

Fisher’s exact test compares categorical data from

small sample sizes. This test accurately calculates

the significance of the deviation from a null hypothe-

sis using the p-value, providing a more reliable result

than other methods. Unlike alternative methods, ex-

act significance tests do not require a well-distributed

or balanced sample, which aligns well with the char-

acteristics of our sample (Mehta and Patel, 1996). We

established a 95% confidence interval (i.e., 0.05) to

reduce errors in the findings. To perform the Fisher

exact test

6

, we formulated the hypotheses as follows:

H0 - The experience of the professional does not af-

5

https://www.statstest.com/fischers-exact-test/.

6

We ran tests from https://astatsa.com/.

fect the acceptance of the guidelines. and H1 - The

experience of the professional affects the acceptance

of the guidelines. The p-value results for each TAM

question are presented in Table 9, which leads us to

accept the null hypothesis for all questions. The re-

sults suggest no statistical evidence that professional

experience affects the acceptance of the guidelines.

Table 9: Exact Fisher test results.

TAM

Professional

experience

1 2 3 4 p-value

E1

<3 years 0 2 7 4

0,26023 to 5 years 0 1 3 5

>5 years 0 4 5 1

E2

<3 years 2 4 4 3

0,51293 to 5 years 0 1 6 2

>5 years 3 1 4 2

E3

<3 years 0 3 5 5

0,65313 to 5 years 0 2 4 3

>5 years 0 5 2 3

E4

<3 years 1 1 5 6

0,09483 to 5 years 0 4 0 5

>5 years 1 4 3 2

U1

<3 years 0 2 8 3

0,28493 to 5 years 0 0 4 5

>5 years 2 2 5 2

U2

<3 years 0 4 4 5

0,08013 to 5 years 0 0 3 6

>5 years 1 2 6 1

U3

<3 years 0 4 6 3

0,22743 to 5 years 0 0 6 3

>5 years 2 1 6 1

U4

<3 years 0 0 5 8

0,23553 to 5 years 0 0 2 7

>5 years 1 1 5 3

F1

<3 years 1 2 0 10

0,03643 to 5 years 0 0 4 5

>5 years 0 3 3 4

F2

<3 years 1 1 1 10

0,22483 to 5 years 0 0 2 7

>5 years 0 2 4 4

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

482

6 DISCUSSION

This article proposed a catalog of guidelines to help

professionals select and apply UX research. The

guidelines were developed from an SLR previously

published by the second author (Martinelli et al.,

2022). This approach of constructing guidelines

based on experiences extracted from the literature and

categorizing them is similar to the work (Kervyn de

Meerendr

´

e et al., 2019). Additionally, similar to the

(Oliveira et al., 2023) proposal, our catalog is a tool to

assist professionals in selecting UX practices. How-

ever, our proposal is more comprehensive than the

cited works, as it presents more than guidelines and

categories. The catalog joins a set of useful informa-

tion to adopt UXR practices, such as the professionals

involved in that practice, UXR methods that can be

adopted, as well as suggestions on how to implement

the practices (see an example in Figure 1).

In contrast to previous studies (Alhadreti, 2020;

Kieffer et al., 2019) our guidelines are not strictly tied

to software development stages, allowing for more

flexibility in their implementation. Our guidelines are

intended to address the lack of knowledge about UX

methods and the incorporation of UX Research into

agile practices, topics discussed by literature (Ma-

jrashi and Al-Wabil, 2018; Rivero and Conte, 2017;

Meingast et al., 2013). The catalog serves as a source

of knowledge that can help professionals in compa-

nies to find the practices that best suit their needs, as

evidenced by the results of the catalog evaluation (see

Section 5.1).

Considering the evaluation, we see that the partic-

ipants generally found the guidelines useful for con-

ducting UX Research activities and expressed inter-

est in utilizing them in the future (see Figures 2 and

3). This overview suggests a positive reception of

the guidelines and the catalog among professionals in

the software industry. Our results also revealed that

novices recognize the guidelines and the catalog as a

valuable resource to assist them in their daily work

(see Section 5.1).

We also verified whether the participants’ profes-

sional profiles impacted the guidelines’ acceptance.

We considered the company type they worked for, i.e.,

startups or established companies, and their years of

experience (see Section 5.2). From statistical tests, we

concluded that the participants’ profiles did not sig-

nificantly impact the acceptance of guidelines. This

confirmed that the guidelines can be adopted by pro-

fessionals of different job positions and from different

companies.

7 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we presented a set of 14 guidelines

to support software professionals in the implemen-

tation of UXR practices. The guidelines were elab-

orated based on extractions from the literature that

considered UXR practices applied in the industry.

The guidelines were grouped into categories and pre-

sented recommendations for applying UX Research

methods and techniques. We developed an online

interactive catalog to make it accessible from the

web. We evaluated the acceptance of guidelines with

32 UX and software professionals who worked from

both startups and established companies.

The results showed that our guidelines were useful

for professionals from startups and established com-

panies, regardless of their experience levels in the

software industry. Participants from both groups ex-

pressed positive feedback about the tool’s ease of use,

perceived usefulness, and use intention. As positive

points, the professionals were enthusiastic about us-

ing the catalog and highlighted the quality of the con-

tent in the GURiP tool. However, the amount of text

in the guidelines, the navigation of the catalog, and

the color contrast of the texts are negative points of

the GURiP tool from professionals.

As contributions, our study provides evidence that

the guidelines are beneficial for professionals en-

gaged in UX Research activities, particularly for be-

ginners. These initiatives aim to address an identi-

fied gap in the literature by offering practical support

and guidance to professionals, especially those in the

early stages of their careers. In future work, we plan

an assessment to check whether the suggested prac-

tices, methods, and techniques can meet the needs of

UX Research. Besides, we will conduct a usability

evaluation of the online catalog.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the support of grant #2020/11441-1,

S

˜

ao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant

309497/2022-1 and 147915/2022-8, Conselho Na-

cional de Desenvolvimento Cient

´

ıfico e Tecnol

´

ogico

(CNPq - Brazil), and grant by the Coordenac¸

˜

ao

de Aperfeic¸oamento de Pessoal de N

´

ıvel Superior -

Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Guiding the Adoption of UX Research Practices: An Approach to Support Software Professionals

483

REFERENCES

Alhadreti, O. (2020). Exploring UX Maturity in Software

Development Environments in Saudi Arabia. Inter-

national Journal of Advanced Computer Science and

Applications (IJACSA), 11(12):168–174.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A

Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Sage

Publications.

Charters, E. (2003). The use of think-aloud methods

in qualitative research an introduction to think-aloud

methods. Brock Education Journal, 12(2).

Corbin, A. S. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Tech-

niques and procedures for developing grounded the-

ory. Citeseer.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease

of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technol-

ogy. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 3, pages 319–340.

Dias, G. A., da, S. P. M., Delfino Jr., J. B., and Almeida, J.

R. d. (2011). Technology Acceptance Model (TAM):

avaliando a aceitac¸

˜

ao tecnol

´

ogica do Open Journal

Systems (OJS). Informac¸

˜

ao & Sociedade: Estudos,

21(2).

Farrell, S. (2017). UX Research Cheat Sheet. https://

www.nngroup.com/articles/ux-research-cheat-sheet/.

Nielsen Norman Group (NNGroup). Online; accessed

22 March 2021.

Garland, R. (1991). The mid-point on a rating scale: Is it

desirable. Marketing bulletin, 2(1):66–70.

Gibbs, G. (2018). Analyzing Qualitative Data. SAGE Pub-

lications Ltd, 2 edition.

Hassenzahl, M. (2018). The Thing and I (Summer of ‘17

Remix): From Usability to Enjoyment. Springer In-

ternational Publishing, page 17–31.

Hokkanen, L. and V

¨

a

¨

an

¨

anen-Vainio-Mattila, K. (2015). UX

Work in Startups: Current Practices and Future Needs.

In Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Ex-

treme Programming, pages 81–92, Cham. Springer In-

ternational Publishing.

Johns, R. (2005). One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Selecting Re-

sponse Scales For Attitude Items. Journal of Elec-

tions, Public Opinion and Parties, 15(2):237–264.

Kashfi, P., Feldt, R., and Nilsson, A. (2019). Integrating UX

principles and practices into software development or-

ganizations: A case study of influencing events. Jour-

nal of Systems and Software, 154:37–58.

Kervyn de Meerendr

´

e, V., Rukoni

´

c, L., and Kieffer, S.

(2019). Overcoming Organizational Barriers to the In-

tegration of UX Methods in Software Development: A

Case Study. In Design, User Experience, and Usabil-

ity. Practice and Case Studies, volume 11586, pages

263–276, Cham. Springer International Publishing.

Kieffer, S., Rukonic, L., de Meerendr

´

e, V. K., and Vander-

donckt, J. (2019). Specification of a UX Process Ref-

erence Model towards the Strategic Planning of UX

Activities. In Proceedings of the 14th International

Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and

Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISI-

GRAPP 2019), volume 2, pages 74–85. SCITEPRESS

– Science and Technology Publications.

Kitchenham, B. and Charters, S. (2007). Guidelines for

performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Soft-

ware Engineering. Technical Report EBSE 2007-001,

Keele University and Durham University Joint Report.

Majrashi, K. and Al-Wabil, A. (2018). HCI Practices in

Software-Development Environments in Saudi Ara-

bia. In Cross-Cultural Design. Methods, Tools, and

Users (CCD 2018), pages 58–77, Cham. Springer In-

ternational Publishing.

Martinelli, S., Lopes, L., and Zaina, L. (2022). UX Re-

search in the Software Industry: An investigation of

Long-Term UX practices. Proceedings of the 21st

Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems.

Mehta, C. and Patel, N. (1996). SPSS exact

tests. https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB 27.0.

0/pdf/en/IBM SPSS Exact Tests.pdf. Online; ac-

cessed 01 September 2023.

Meingast, M., Packard, H., Ballew, T., Edwards, R.,

Nordquist, E., Sader, C., and Smith, D. (2013). Ag-

ile and UX: The Road to Integration The Challenges

of the UX Practitioner in an Agile Environment. In

Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics

Society Annual Meeting, pages 1002–1006. Scopus.

Oliveira, S., Cristo, A., Geovane, M., Xavier, A., Silva, R.,

Rocha, S., Marques, L., Gomes, G., Gadelha, B., and

Conte, T. (2023). UXNator: A Tool for Recommend-

ing UX Evaluation Methods. Proceedings of the 25th

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems (ICEIS 2023), 2:336,343.

Pazitka, K. (2019). The UX Research Methods Ev-

ery Designer Needs To Know. https://youtu.be/

gGZGDnTY454?si=E84qMmkEue2f7wvk. Career-

Foundry, 2019. Online; accessed 22 March 2021.

Rivero, L. and Conte, T. (2017). A Systematic Mapping

Study on Research Contributions on UX Evaluation

Technologies. In XVI Brazilian Symposium on Human

Factors in Computing Systems, page 10, New York,

NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Schmidt, M. (2008). The Sankey diagram in energy and

material flow management: Part II: Methodology and

current applications. Journal of industrial ecology,

12:173–185.

Shapiro, S. S. and Wilk, M. B. (1965). An Analysis

of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples).

Biometrika, 52(3/4):591–611.

Silveira, S., Choma, J., Pereira, R., Guerra, E., and Zaina, L.

(2021). UX Work in Software Start-Ups: Challenges

from the Current State of Practice. International Con-

ference on Agile Software Development, pages 19–35.

S

¨

uner-Pla-Cerd

`

a, S., T

¨

ore Yargın, G., S¸ahin, H., and Danıs¸,

S. (2021). Examining the impact of covid-19 pan-

demic on ux research practice through ux blogs. In

Design, User Experience, and Usability: UX Re-

search and Design, volume 12779, pages 579–592,

Cham. Springer International Publishing.

Venkatesh, V. and Bala, H. (2008). Technology acceptance

model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. De-

cision sciences, 39(2):273–315.

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., H

¨

ost, M., Ohlsson, M. C., Reg-

nell, B., and Wessl

´

en (2012). A Experimentation in

software engineering. Springer Science & Business

Media.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

484