Influence of Students’ Choice of

Examination Format on Examination Results

Tenshi Hara

1 a

, Sebastian Kucharski

2 b

, Iris Braun

2

and Karina Hara

3 c

1

Saxon University of Cooperative Education, State Study Academy Dresden, Germany

2

TU Dresden, Faculty of Computer Science, Chair of Distributed and Networked Systems, Germany

3

Blue Pumpkin LLC of Kailua-Kona, HI, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Examination Format, Student Choice, Self-Regulation, Students as Partners.

Abstract:

This study explores the impact of free choice of examination format on student performance in the ‘Pro-

gramming of Mobile Applications’ (PMA) course at the Saxon University of Cooperative Education. The

PMA course, offered in both Information Technology (IT) and Media Informatics (MI) curricula, underwent

changes in examination format, allowing students to choose between a traditional written examination, a pro-

gramming assignment, or a seminar paper. The investigation spans data from 2018 to 2023, encompassing 67

written examinations and 111 choice examinations. Results indicate a nuanced improvement in overall grades

when students opt for non-traditional examination formats. Disregarding fails due to non-submission, the av-

erage grade for choice examinations improves (lower grade is better) to 1.89 compared to 2.10 for written

exams. Notably, students exhibit a nearly one sub-grade enhancement in performance. The choice between

programming assignments and seminar papers does not significantly impact grades. However, compared to

traditional written examinations, flexibility in assessment formats positively influences student outcomes, en-

hancing overall student performance and emphasising the benefits of creative flexibility and alignment with

individual interests in assessment practices.

1 INTRODUCTION

At the Saxon University of Cooperative Education

(Berufsakademie Sachsen; BAS) the course ‘Program-

ming of Mobile Applications’ (PMA) is offered as

an elective in the Information Technology (IT) cur-

riculum in the fourth semester as well as in the Media

Informatics (MI) curriculum in the fifth semester.

The PMA course in the IT curriculum is a leg-

acy course predating the authors’ affiliation with BAS

with a written exam at the end of the semester. In

2019, the same PMA course was introduced into the

MI curriculum. However, the exam was a program-

ming assignment. Students were tasked to complete a

small project of their own choosing within the twelve

weeks of on-premise lectures.

In 2020, in light of the Corona pandemic, the

examination format in the MI version of the course

was changed to a free choice of either a program-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5460-4852

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-4210-5281

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7843-1685

ming assignment or a seminar paper of roughly fifteen

pages. The students are free to choose the examina-

tion format individually. Independent of the choice,

the semester now concludes with a brief oral presenta-

tion on either the application programmed or the sem-

inar paper written.

In 2022, the same free choice of examination

format was also introduced in the IT version of the

PMA course.

At BAS, all study programmes are dual, i.e.

practice-integrated Bachelor’s programmes of six

semesters. The practice-integrated dual study pro-

gramme combines theoretical academic education

with practical work experience. Dual study pro-

grammes aim to integrate theoretical knowledge

gained in academic courses with practical experi-

ence in the workplace. Students spend part of their

time attending classes on campus and the remain-

ing time working at a partner company gaining real-

world work experience. Thus, work phases are an

integral part of the dual study programme. Students

switch between practice and theory roughly every fif-

teen weeks.

Hara, T., Kucharski, S., Braun, I. and Hara, K.

Influence of Students’ Choice of Examination Format on Examination Results.

DOI: 10.5220/0012605400003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 2, pages 495-500

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

495

The idea of leaving the choice of examination

format to the students was based on the desire to better

cater for the different study interests of the students.

It is in the nature of BAS’s practice-integrated degree

programmes that there are students who are primarily

focused on starting a career in the free market eco-

nomy after graduation and those who prefer to con-

tinue their academic studies with a Master’s degree or

work in a research institution.

The programming assignment is more suited to

students who want to start their free market careers,

while the seminar paper is more suited to students

who want to concentrate on research. In the course

of an informal oral survey, almost all students with a

programming assignment stated that the assignment

better prepared them for later work in the free market

economy. The seminar paper is a good trial run for

the Bachelor’s thesis due in the sixth semester. The

majority of students who opt for the seminar paper

prepare the literature review for the Bachelor’s thesis.

The proportion of students who define the topic of

the Bachelor’s thesis with their supervisor at the dual

practice partner company through the seminar paper

is also not insignificant.

We took the opportunity to analyse the influence

of the examination format on examination results. In

this article, we would like to present our findings

based on data from 2018 until 2023.

2 RELATED WORK

The PMA course at BAS is designed with the goal of

maximising students’ ability to attain self-regulation

as envisioned by (Zimmerman et al., 2000). Thus,

addressing the examination format is the next lo-

gical step in our ongoing research after investigating

– amongst others – assessment support (e.g., (Braun

et al., 2018)) and Audience Response Systems (e.g.,

(Kubica et al., 2019)).

Investigating the influence of examination format

on student performance has moved well beyond the

difference in formative and summative assessment

(e.g. (Bloom et al., 1971)) and can now be considered

well established and regularly resurfaces amongst re-

search work (e.g., (Mulkey and O’Neil Jr, 1999; My-

ers and Myers, 2007; Peters et al., 2017)). Of-

ten, the research questions investigated address costs

(e.g. (Biolik et al., 2018)), performance comparis-

ons between two examination formats (e.g. (Davison

and Dustova, 2017)), or fairness and equality aspects

of examinations in the context of specific disabilities

(e.g. (Vogel et al., 1999; Riddell and Weedon, 2006;

Ricketts et al., 2010)).

In 2022, (Schultz et al., 2022) investigated per-

ceptions and practices of assessment in the con-

text of STEM courses, primarily focusing on work-

readiness. Four aspects were identified with respect to

assessments: 1) skills that will be used in future work-

places, 2) testing scientific concepts, 3) critical think-

ing or problem-solving skills, and 4) student choice

or input into the assessment. However, (Schultz et al.,

2022) then moved on to building an online tool for

self-assessment and investigating obstacles related to

assessment design. Thus unfortunately, the critical

fourth aspect was not investigated deeper.

A test of flexible examination formats was car-

ried out by (Diedrichs et al., 2012) in the context

of a teacher training programme. Teacher trainees

choose one of four examination formats at the start

of the course. Additionally, they were allowed to

propose their own examination format. Interestingly,

they chose the examination format that they expected

to be the easiest path towards high grades.

As far as the authors are aware, only two stud-

ies on students’ choice of examination format have

been published: (Irwin and Hepplestone, 2012) and

(Rideout, 2018).

(Irwin and Hepplestone, 2012) investigated the

impact of flexible assessment formats with respect to

students’ ability to present findings. The target was

to increase flexibility and give learners more control

over the assessment process. They focused on the

role of technology in facilitating choice of assessment

format. We agree with (Irwin and Hepplestone, 2012)

that their work is of interest to readers considering

implementing changes to the assessment process to

increase student ownership and control.

(Rideout, 2018) presents a practical and success-

ful strategy for flexible assessment. When imple-

mented, a flexible approach to assessment has the

potential to enhance students’ engagement and aca-

demic accomplishments by allowing them to custom-

ise their learning experience. They examined the de-

cisions made by 2016 students across 12 sections of

two distinct courses utilising their approach. The ana-

lysis delves into the connections between students’

choices and their academic achievements. Students

were given the choice to adhere to the teachers’ pro-

posed assessment scheme or to modify it by selecting

specific assessments and determining their respective

weights in calculating the final grade. Notably, ap-

proximately two-thirds of students opted for modi-

fications. Noteworthy, students did not lean towards

minimising their workload by selecting the minimum

number of assessments. The most prevalent alteration

made by students was opting out of a substantial as-

signment. Despite the variety of choices made, there

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

496

were no substantial differences in academic achieve-

ment associated with these decisions.

Surprisingly, the observation by (Rideout, 2018)

that students do not choose to minimise their

workload stands in contrast to the observation by

(Diedrichs et al., 2012) that teachers tend to choose

the easiest path for their students. In our opinion,

these observations are not contradictory. The subjects

of (Diedrichs et al., 2012) were trainee teachers who

themselves were assessed for their performance. We

conclude that the trainee teachers assumed that posit-

ive student performance would have a positive effect

on their own assessments and therefore chose the path

of least effort for their students.

We concur with (Irwin and Hepplestone, 2012)

and (Rideout, 2018). However, we have identified a

strong need to ensure and be able to prove the compar-

ability of the various forms of examination in a legally

secure manner. In the context of this challenge, how-

ever, the aforementioned, well-established research

results can be used to justify the equivalence of the ex-

amination forms with regard to proof of achievement

of the course objectives. Thus, the free choice gran-

ted to students is in fact only a choice of examination

form, but not of examination content or difficulty.

3 EXAMINATION DATA

The data we took into account for the written examin-

ations in the IT version of the course comes from the

years 2018 to 2021. The data for the freely chosen ex-

amination forms comes from the years 2019 to 2023

in the MI version of the course and from the years

2022 and 2023 in the IT version of the course. A total

of 67 written examinations, 95 programming assign-

ments and 16 seminar papers were taken into account.

Of these 178 examinations, two were discarded in the

later steps of our significance analysis. The average

overall grades are summarised in Table 1.

It should be noted that all iterations of the course

in the time frame (2018 until 2023) were instructed

by the same teacher. Thus, the teacher can be ruled

out as an influence factor.

At BAS, grades range from 1.0 (‘very good’; best

achievable grade) to 5.0 (‘insufficient’; fail). The

passing grade of 4.0 (‘sufficient’) is achieved when

students fulfil at least 50% of the examination re-

quirements. The passing grades can be divided into

sub-grades by raising or lowering by 0.3:

• rating ‘very good’: 1.3,

• rating ‘good’: 1.7 as well as 2.3,

• rating ‘satisfactory’: 2.7 as well as 3.3, and

• rating ‘sufficient’: 3.7.

We would like to point out that the score of 3.0

corresponds to the students achieving exactly the ob-

jectives of the course specified in the module hand-

book. Only if the objectives are exceeded, a 2.0 is

justified. Thus, we want to emphasise that students of

the PMA course already performed above the object-

ives before the free choice of examination format was

introduced (average grade 2.10; cf. Table 2).

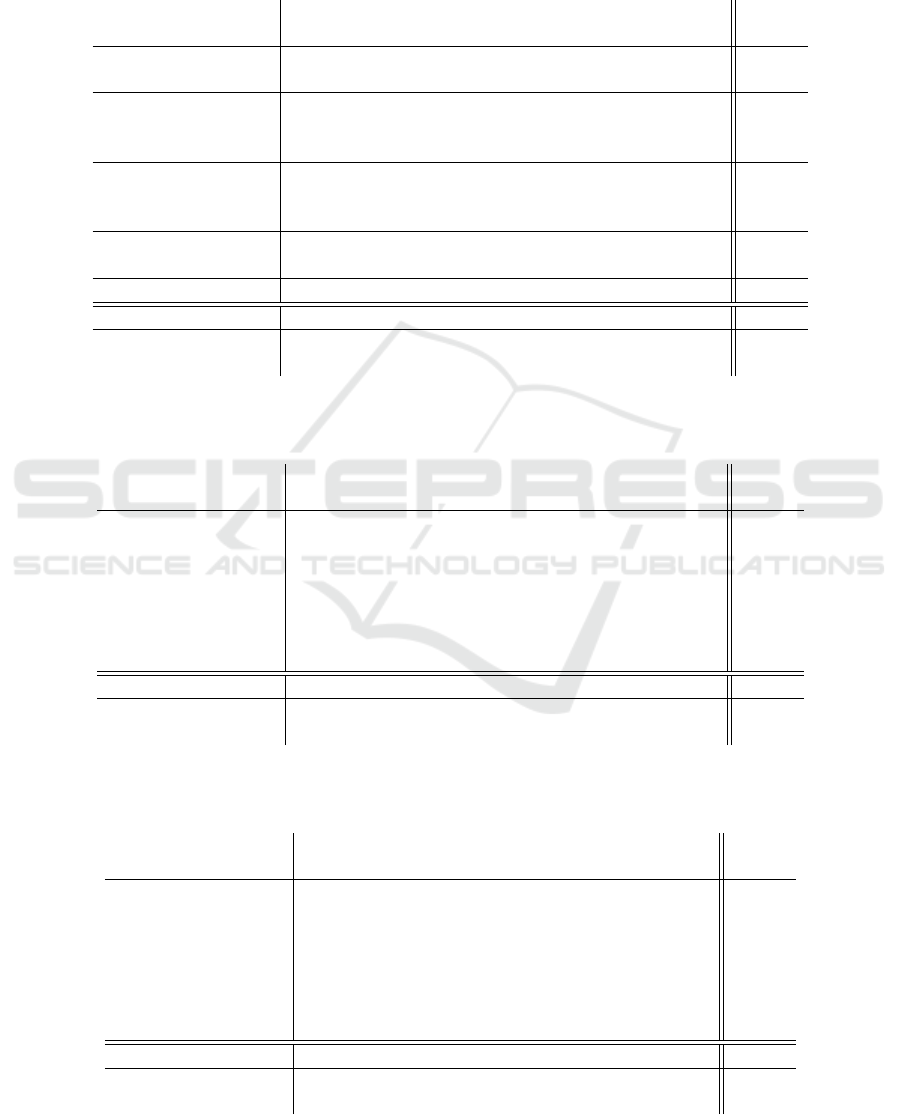

Table 1: average examination grades.

examination format average grade

written 2.10

free choice

1.95 1.89

(with fails) (without fails)

3.1 Including Non-Passing Grades

From the results of the written examinations (cf.

Table 2) and choice examinations (cf. left average in

Table 1 and numbers in parenthesis in Table 3) a na

¨

ıve

difference of 0.15 can be derived with respect to the

average examination grade. Thus, moving away from

written exams improves the overall examination suc-

cess. However, the improvement only equates to half

of a sub-grade.

If we take a closer look at these na

¨

ıve numbers,

the two failed examinations (non-passing grade 5.0)

have a considerable influence on the average values,

especially for the seminar papers (cf. Table 5). It is

therefore worth investigating whether the failed sem-

inar papers can be disregarded.

3.2 Disregarding Non-Passing Grades

Disregarding the fails (non-passing grades 5.0)

among the programming assignments and seminar pa-

Table 2: written examination results.

grade rating 2018 2019 2020 2021 total

1.0

very good

0 0 2 2 4

1.3 2 2 1 4 9

1.7

good

3 3 5 5 13

2.0 3 3 1 6 13

2.3 3 4 0 3 10

2.7

satisfactory

0 0 1 2 3

3.0 1 1 1 2 5

3.3 0 0 0 2 2

3.7

sufficient

1 0 1 1 3

4.0 0 0 1 1 2

5.0 insufficient 0 0 0 0 0

median grade 2.0 2.0 1.7 2.0 2.0

average grade 2.10 1.99 2.09 2.15 2.10

Influence of Students’ Choice of Examination Format on Examination Results

497

pers, the average grades improves considerably: the

overall average improves by 0.21 to 1.89 which cor-

responds to a 70% improvement of a sub-grade.

We are aware that the question can now legit-

imately be asked as to whether the failed examina-

tions can simply be disregarded. Exceptionally, ignor-

ing the fails is valid because the non-passing grades

were given due to the students not handing in their

programmes and/or papers rather than insufficient

achievements. If students do not take an examina-

tion due to illness, they should actually submit a sick

note. If they are not satisfied with their examination

performance before the submission deadline, they can

withdraw from the examination. However, some stu-

dents neither submit the sick note nor withdraw from

the examination (in time), which is why they are then

graded with a non-passing 5.0. Thus, we can disreg-

ard the fails and compare the written exams (which

had no fails) with a clean set of choice examinations

(now also without fails).

The option to choose between the programming

assignment and the seminar paper seems to have

no significant influence on the examination grades

between these two examination formats: The average

grades are almost on par with 1.89 (programming as-

signment; cf. Table 4) and 1.88 (seminar paper; cf.

Table 5). However, these averages do show a signi-

ficant improvement of 0.21 in favour of choice ex-

aminations versus written examinations. Students are

able to improve their exam performance by almost

one sub-grade.

Interestingly, the median score does not improve

and remains at 2.0, which is a good score.

In view of these results, we conclude that the stu-

dents are improving on average and are tending to

level off at the good performance level. Students

are therefore not only improving on average, but the

spread of grades is also decreasing. Thus, free choice

of examination format does actually increases student

ownership and control as postulated by (Irwin and

Hepplestone, 2012).

3.3 Optional: Disregarding Outliers

Explicitly pointing out that the following considera-

tion is not statistically sound, we would like to discuss

that the data collected can be thinned out even further

by disregarding the two seminar papers from the year

2022. Each is the sole seminar paper in its corres-

ponding degree programme, while all other students

opted for a programming assignment. These two sem-

inar papers might therefore be regarded as outliers for

which neither the grade average nor the median can

be meaningfully considered.

If the two seminar papers are removed, the sem-

inar papers’ grade average improves to 1.78 and the

median improves to 1.7. This once again underlines

our conclusion from the previous section, namely

that students’ performances improve with free choice

of examination format. As mentioned, however, it

should be noted that disregarding the two seminar pa-

pers may be contestable.

4 CONCLUSION

We conclude that moving away from written exams in

this programming- and research-intensive course im-

proves students’ overall performance. Programming

is a creative process, as is often said. One can’t be

creative on command, certainly not in the context of

a written exam under time pressure. Giving students

more leeway allows them to be creative at appropriate

times. By choosing the preferred topic and form of

their examination, students also work on topics that

actually interest them. In a written examination, the

assignments are predetermined, regardless of the stu-

dents’ interests.

The concept of allowing students to choose their

preferred examination format was not the focus of

previous research (cf. section 2). We assume that

legal boundaries prohibit such free choice of exam-

ination format. In general, at Saxon universities – as

is true for most German universities –, the examina-

tion format must be defined in the course description

in the module handbook (§ 35 (1) point 6 in conjunc-

tion with § 36 (2) S

¨

achsHSG in conjunction with § 16

HRG). Thus, offering multiple examination formats is

restricted to modules that have explicitly listed mul-

tiple examination formats in the module description.

So defined courses are very rare; most courses define

exactly one examination format. Those that exist,

have the multiple examination formats defined not for

the benefit of the students, but for the teachers (similar

to the situation described in (Diedrichs et al., 2012)).

This is highlighted by the absence of phrasing such

as ‘The students choose. . . ’, instead having variations

of ‘The module coordinator determines the form of

examination at the beginning of the semester’.

For the purpose of this research, students were

asked to participate in the presented examination

format experiments. They were offered a repeat ex-

amination conforming to the format defined in the

module description if they felt their grade was un-

warranted or they were unsatisfied with their grade in

general. No student opted for a repeat examination. In

light of the very positive results of our investigations,

we formalised the students’ free choice of examina-

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

498

tion format in the descriptions in the module hand-

books of the IT and MI programmes at BAS in 2023.

Starting winter semester of 2023, students can now

choose in accordance with the rules and with legal

certainty between programming assignment and sem-

inar paper in the PMA course, and between a written

exam and a seminar paper in the Data Management

Systems course. We expect to see the same positive

impact on this second course. At BAS we plan to ex-

tend the list of courses with choice of examination

format even further in the future. The new election

model could also be of particular interest to the co-

authors’ institutions. Should the opportunity for field

trials arise, we want to investigate whether the results

from BAS can be reproduced at those institutions. We

are also considering contacting previous collaborators

to conduct field trials at their institutions. Such field

tests could also allow conclusions to be drawn about

what influence, if any, the teacher has on the results.

REFERENCES

Biolik, A., Heide, S., Lessig, R., Hachmann, V., Sto-

evesandt, D., Kellner, J., J

¨

aschke, C., and Watzke,

S. (2018). Objective structured clinical examina-

tion “death certificate” station–computer-based versus

conventional exam format. Journal of forensic and

legal medicine, 55:33–38.

Bloom, B. S. et al. (1971). Handbook on formative and

summative evaluation of student learning. ERIC.

Braun, I., Hara, T., Kapp, F., Braeschke, L., and Schill, A.

(2018). Technology-enhanced self-regulated learning:

Assessment support through an evaluation centre. In

2018 IEEE 42nd Annual Computer Software and Ap-

plications Conference (COMPSAC), volume 1, pages

1032–1037. IEEE.

Davison, C. B. and Dustova, G. (2017). A quantitative

assessment of student performance and examination

format. Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, 18.

Diedrichs, P., Lundgren, B. W., and Karlsudd, P. (2012).

Flexible examination as a pathway to learning. Prob-

lems of Education in the 21st Century, 40:26.

Irwin, B. and Hepplestone, S. (2012). Examining increased

flexibility in assessment formats. Assessment & Eval-

uation in Higher Education, 37(7):773–785.

Kubica, T., Hara, T., Braun, I., Kapp, F., and Schill, A.

(2019). Choosing the appropriate audience response

system in different use cases. Systemics, Cybernetics

and Informatics, 17(2):11–16.

Mulkey, J. and O’Neil Jr, H. (1999). The effects of test item

format on self-efficacy and worry during a high-stakes

computer-based certification examination. Computers

in Human Behavior, 15(3-4):495–509.

Myers, C. B. and Myers, S. M. (2007). Assessing assess-

ment: The effects of two exam formats on course

achievement and evaluation. Innovative Higher Edu-

cation, 31:227–236.

Peters, O., K

¨

orndle, H., and Narciss, S. (2017). Effects of

a formative assessment script on how vocational stu-

dents generate formative feedback to a peer’s or their

own performance. European Journal of Psychology of

Education.

Ricketts, C., Brice, J., and Coombes, L. (2010). Are mul-

tiple choice tests fair to medical students with specific

learning disabilities? Advances in health sciences

education, 15:265–275.

Riddell, S. and Weedon, E. (2006). What counts as a reas-

onable adjustment? dyslexic students and the concept

of fair assessment. International Studies in Sociology

of Education, 16(1):57–73.

Rideout, C. A. (2018). Students’ choices and achievement

in large undergraduate classes using a novel flexible

assessment approach. Assessment & Evaluation in

Higher Education, 43(1):68–78.

Schultz, M., Young, K., K. Gunning, T., and Harvey, M. L.

(2022). Defining and measuring authentic assessment:

a case study in the context of tertiary science. Assess-

ment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(1):77–94.

Vogel, S. A., Leyser, Y., Wyland, S., and Brulle, A. (1999).

Students with learning disabilities in higher education:

Faculty attitude and practices. Learning Disabilities

Research & Practice, 14(3):173–186.

Zimmerman, B. J., Boekarts, M., Pintrich, P., and Zeidner,

M. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: a social cognit-

ive perspective. Handbook of self-regulation, 13.

Influence of Students’ Choice of Examination Format on Examination Results

499

APPENDIX

Table 3: Overall choice examination results.

(in parenthesis: with fails)

(this is an aggregation of Tables 4 and 5 including all empty rows omitted there)

grade rating 2019 2020 2021

2022 2023

total

IT MI IT MI

1.0

very good

0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1

1.3 2 11 5 1 1 2 6 28

1.7

good

3 3 3 3 2 5 3 22

2.0 1 1 3 9 5 4 2 25

2.3 4 1 5 1 9 0 4 24

2.7

satisfactory

0 0 0 1 0 3 2 6

3.0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 2

3.3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

3.7

sufficient

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

4.0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

5.0 insufficient 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 2

median grade 2.0 1.3 1.7 2.0 2.2 2.0 2.0 2.0

average grade 2.05 1.45

1.95

1.96 2.08

1.94

1.85

1.89

(2.11) (2.15) (1.95)

Table 4: Programming assignment results.

(rows without entries omitted; in parenthesis: with fails)

grade rating 2019 2020 2021

2022 2023

total

IT MI IT MI

1.3 very good 2 10 5 1 1 2 3 24

2.0 good 1 1 1 9 5 4 2 23

2.3 good 4 0 3 1 8 0 4 20

2.7 satisfactory 0 0 0 0 0 3 1 4

3.0 satisfactory 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 2

3.7 sufficient 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

5.0 insufficient 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1

median grade 2.0 1.3 1.7 2.0 2.2 2.0 2.0 2.0

average grade 2.05 1.44 1.91 1.91 2.07

1.94

1.93

1.89

(2.15) (1.92)

Table 5: Seminar paper results.

(rows without entries omitted; in parenthesis: with fails)

grade rating 2019 2020 2021

2022 2023

total

IT MI IT MI

1.0 very good 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1

1.3 very good 0 1 0 0 0 0 3 4

1.7 good 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 2

2.0 good 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 2

2.3 good 0 1 2 0 1 0 0 4

2.7 satisfactory 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 2

5.0 insufficient 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1

median grade n/a 1.3 2.4 2.7 2.3 n/a 1.3 2.0

average grade n/a 1.53

2.06

2.70 2.30 n/a 1.66

1.88

(2.55) (2.08)

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

500