The Role of Privacy and Security Concerns and Trust in Online

Teaching: Experiences of Higher Education Students in the Kingdom

of Saudi Arabia

Basmah Almekhled

1,2 a

and Helen Petrie

1b

1

Department of Computer Science, University of York, Heslington East, York, U.K.

2

College of Computing and Informatics, Saudi Electronic University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Keywords: Online Higher Education, Privacy and Security Concerns in Online Teaching, Trust in Online Teaching,

Videoconferencing Technologies, Webcam Use.

Abstract: Higher education institutions (HEIs) are increasingly using online teaching, particularly since the COVID-19

pandemic. Numerous digital technologies are now used in online teaching, such as videoconferencing for

online classes. This has raised privacy and security concerns for students, as well as a reluctance to have

webcams on during online classes. This study investigated the privacy and security concerns in online

teaching of HEI students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), as well as their trust in a range of actors and

entities involved in online teaching. It also investigated their use of webcams and their reasons for having

their webcams off during online classes. The study was conducted in the real-world context of online courses

at a HEI in KSA. It found high levels of concern about online privacy in relation to the institution, but

moderate levels in relation to instructors and classmates and in relation to online security. Complex,

unexpected relationships were found between online privacy and security concerns and trust. As with previous

research, students were reluctant to have their webcams on for a variety of reasons, often concerned with

privacy of personal information. Only trust in instructors was a significant predictor of whether students were

likely to have their webcams on during online classes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Online teaching has become increasingly popular in

recent years, especially since the COVID-19

pandemic. Although many higher education

institutions (HEIs) were already using online systems

such as virtual learning environments (VLEs) before

the pandemic, the use of a range of different digital

technologies greatly increased when HEIs moved to

fully or nearly fully online teaching as a result of the

pandemic. The move to online teaching has also

highlighted issues around the privacy and security of

these technologies for students.

A number of studies in different countries have

investigated HEI students’ privacy and security

concerns about online teaching during the pandemic.

These concerns include being recorded without

permission during online classes, not knowing where

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9985-7869

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0100-9846

personal information and recordings are stored and

who has access to them, unauthorised people entering

and disrupting online classes, and the need to have

webcams on during online classes. Cultural and

contextual variations add layers of complexity in

understanding these concerns.

Our study explores the relationships between

privacy, security, and various forms of trust in online

teaching. Trust can take various forms, for example

interpersonal, institutional, and technological. It may

play an important role in students’ experience of

online teaching. This study also explores the use of

videoconferencing technology, particularly the use of

webcams, in online teaching. Previous research has

identified students' reservations about webcam use,

relating to anxiety, shyness, and privacy issues.

Our research questions are:

RQ1: For HEI students in the Kingdom of Saudi

Arabia (KSA), what are the levels of concern about

66

Almekhled, B. and Petrie, H.

The Role of Privacy and Security Concerns and Trust in Online Teaching: Experiences of Higher Education Students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

DOI: 10.5220/0012616200003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 66-77

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

online privacy, security and trust in a range of actors

and entities in online teaching?

RQ2: For KSA HEI students, what is the relationship

between trust in different actors and entities in online

teaching and their privacy and security concerns

about online teaching?

RQ3: For KSA HEI students, what are the levels of

webcam use and attitudes to webcams in online

teaching?

RQ4: With respect to privacy and security concerns

and trust in online teaching, how do these affect KSA

students’ use of webcams in online teaching?

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Students’ Privacy and Security

Concerns in Online Teaching

Many researchers fail to discuss what they

specifically mean by online privacy and security

concerns when discussing these concepts. However,

the privacy and security issues of online teaching

have been analysed for a number of different

contexts, including privacy in collaborative tasks

(Patil & Kobsa, 2005), protecting students' privacy

and security in online teaching environments (by this

term we mean not just the VLE, but the whole

environment, which may include a range of

technologies) (Anwar & Greer, 2012), preserving

students' personal and private information during

online discussions (Booth, 2012), and maintaining

privacy on social networking sites used for online

teaching (Salmon et al., 2015).

Recently, Kularski and Martin (2021) conducted

a systematic review of issues related to online privacy

for HEI students and identified 41 relevant papers.

Most of these papers focused on students’ online

privacy on social network sites and their online

privacy beliefs and behaviours in those environments.

However, the authors identified a lack of research on

privacy concerns in online classes and students’

perceptions of interacting and sharing information in

online teaching environments.

Since online teaching environments allow

students to interact, edit, share, and study using

personal and private information sources, security

concerns have also gained importance. As a result, it

is critical to restrict access to information and

resources to authorised users and to safeguard the

privacy, accessibility, and integrity of the online

teaching environment for those users (Aldheleai et al.,

2015). Students' information should not be

compromised by an online teaching environment, and

it should be well secured (Zhang & Nunamaker,

2003). For instance, it matters whether or not students

are being recorded during online classes, as well as

who may access the recordings (especially academic

staff members) and where the recordings will be

stored.

Greater dependence on digtal technologies for

teaching has brought a new set of online privacy

concerns for both students and instructors. Privacy

concerns differ by context and might shift over time

among different communities. New privacy concerns

may arise, and privacy agreements may need to be

amended and tailored to new sets of people or a new

context (Martin, 2016). In a recent study exploring

the attitudes and concerns of HEI students regarding

the use of technology in online teaching and studying,

distinctions emerged between Saudi Arabian and

British students regarding their concerns about online

privacy and security about the use of chat

technologies (Almekhled & Petrie, 2023a & b).

Nevertheless, both Saudi and British students showed

similar concerns related to online privacy and security

when considering the use of video conferencing for

online teaching. Also, British students' ratings of their

concerns about online security and privacy were low,

but further investigation through open-ended

questions revealed concerns such as unauthorised

recording of online classes, disruptions during

classes, and uncertainty about data access.

Smith et al. (2011) noted that it can be practically

impossible to assess privacy overall when

considering the diverse definitions of privacy. Given

that privacy depends on context, and its measurement

will likewise depend on context. The choice of

privacy concern measurement scales in this study is

driven by a consideration of the online teaching

context. Numerous researchers have developed scales

to measure online privacy concerns. For example, the

scales about Internet users’ concerns about the

privacy of their information developed by Malhotra

et al. (2004) and Buchanan et al. (2007) were not used

due to their emphasis on general technology-related

concerns and lack of consideration of crucial

dimensions in online teaching. Liu et al.'s (2018)

scale was also considered unsuitable as it measures

privacy risk rather than concerns about privacy.

In contrast, the Concern for Information Privacy

Scale (CFIP), initially developed by Smith et al.

(1996) and later adapted by Peng and Dutta (2022),

was selected due to its suitability in evaluating the

privacy concerns of students about online teaching.

This scale addresses a broad range of concerns related

to personal information and its reliability in the

context of online teaching research has been

The Role of Privacy and Security Concerns and Trust in Online Teaching: Experiences of Higher Education Students in the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia

67

demonstrated. In addition, the scale developed by

Kim (2021) is useful in providing an understanding

of students' privacy and security concerns during

online classes. It allows for the identification of

specific concerns, such as unauthorised access and

monitoring during online classes. Finally, we

developed new items to measure privacy concerns

about the student’s location and personal space in

online teaching classes and concerns about the

privacy of information in a range of different online

teaching situations. These were developed as they

were considered important concepts to measure but

were not covered by previous scales.

2.2 Trust in Online Teaching

As with privacy, researchers highlight the complex

nature of trust, and have developed a number of

definitions emphasising different aspects of the

concept. McEvily et al. (2003) gave a definition of

trust as "an expectation, a willingness to be

vulnerable, and a risk-taking act". On the other hand,

Fukuyama (1996) and Van Houtte (2007) emphasized

the communal dimension of trust, defining it as "an

expectation that other members of the community

will behave cooperatively and honestly". Tierney

(2006) introduced the idea that trust is not a static

concept but rather a dynamic process, involving a

series of interactions characterized by risk-taking or

faith. For this study we defined trust as a "firm belief

in the competence of an entity to act dependably,

securely, and reliably within a specific context"

(based largely on the definition from Grandison &

Sloman, 2000). In the context of online teaching, this

belief is what the students have in their instructors and

their classmates and the VLE they are using, as well

as the institution as a whole.

According to Ejdys (2018), research on trust in

technology has considered multiple trust types such

as interpersonal trust, institutional, organizational and

trust in technology per se. In the context of online

teaching, interpersonal trust can take two forms:

within the community of students and the trust

between students and their instructor. In terms of trust

within the community of students, this type of trust is

the assumption that other community members (i.e.,

other students) will behave cooperatively and

honestly (Rice & Schroeder, 2021). In terms of trust

in instructors, according to Cavanagh et al. (2018)

students’ trust in their instructors can be defined as

the belief that the instructor understands the

challenges that students face as they advance through

the course, accepts students for who they are, and

cares about their educational welfare.

Another type of trust is that in an organisation or

institution such as an HEI. Trust in an organisation

can be defined as individuals' positive expectations

about an organisation (Luhmann, 1979; Misztal,

1996). In the context of online teaching, this type of

trust means that students have positive expectations

about their institution that reflect the institution’s care

for its students, its implementation of principles of

ethics and social responsibility in its activities, and its

offering of opportunities for the personal

development of its students.

Thus, trust in online teaching covers a range of

components, reflecting trust in different actors

(instructors, other students) and entities, both

organisational (the institution) and technological (the

VLE, as well as other digital technologies such as

video conferencing, chat, webcams, microphones

which may be used in online teaching). Participating

in online teaching, like all teaching, involves sharing

one’s opinions, information and knowledge, but also

in the case of online teaching, potentially one’s

location and physical environment (e.g., a view of

some of one’s house) with potentially

considerable

self-disclosure. Self-disclosure may lead to privacy

concerns involving such personal information and

how this is shared with others and used by them

(Joinson & Paine, 2006). Self and personal

information disclosure may be very dependent on

trust (Briggs et al., 2004). Trust reduces the perceived

risks of disclosing self and personal information

(Anwar and Greer, 2012; Steel, 1991).

Due to its importance, we investigated the impact

of different types of trust on students' concerns about

privacy and security in online teaching.

2.3 Use of Webcams in Online

Teaching

Previous research has explored the role of webcams

in videoconferencing technologies and their potential

impact on engagement, interaction and learning in

online teaching classes. The expectation is that the

use of webcams can facilitate a more direct and

personal connection between students and instructors,

leading to increased engagement and more active and

meaningful interaction (Giesbers et al., 2013; Gillies,

2008).

A number of studies have investigated HEI

students’ attitudes to the use of webcams in online

teaching and specifically why students do not want to

have their webcams on during online classes

(Almekhled & Petrie 2023a; Bedenlier et al., 2021;

Castelli & Sarvary, 2021; Dixon & Syred, 2022;

Gherheș et al., 2021). These studies have been

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

68

conducted in a number of countries (Saudi Arabia,

Germany, the USA, the United Kingdom, and

Romania, respectively), and all found students were

very reluctant to have webcams on during online

classes. A range of reasons has been found to explain

this reluctance: shyness, anxiety, social norms, and

lack of pressure to turn the webcam on unless the

instructor specifically requests it. All these studies

also highlighted privacy issues as major concerns in

relation to webcam use. However, research has also

shown that if students in online classes cannot see one

another or the instructor, they feel isolated and

disengaged (Pallof & Pratt, 2007; Petchamé et al.,

2022). While previous studies have explored students'

perspectives on webcam use during online teaching,

the connection between privacy and security

concerns, trust, and the use of webcams remains an

unexplored area in the context of online teaching, and

is the focus of our research.

3 METHOD

3.1 Design

A study was conducted in a real-world blended

teaching situation at the Saudi Electronic University

(SEU), a blended teaching HEI in Saudi Arabia. The

study targeted undergraduate students taking a range

of synchronous blended courses in computer science,

at all levels of undergraduate study (i.e., Years 1, 2

and 3).

The study took place in Weeks 10 and 11 of

courses which lasted 13 weeks in Spring 2023.

Students take two classes per week for a course, one

online and one in person. Both sessions are lectures

and last one hour.

Students taking part in the study were asked to

complete three questionnaires: one at the start of the

study, one immediately after attending an online class

and one at the end of the study. The questionnaires

were largely based on previously developed

and

validated questionnaires and measured concerns

about privacy, security and trust in the context of

online teaching. Some additional questions were

developed to cover aspects of concerns about online

teaching not covered in previous questionnaires, such

as concern about sharing information about a

student’s location and physical space, use of

webcams and

concerns about webcam use.

In the information provided to participants, our

interest in participants’ webcam use and concerns

about it was deliberately not emphasised This choice

was motivated by the aim of preventing any potential

influence on participants’ natural webcam behaviour

during the targeted online

classes.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from

both the Physical Sciences Ethics Committee at the

University of York and the Ethics Committee at SEU.

3.2 Participants

Students from eight online courses participated in the

study, these courses had a total of 162 students

enrolled in them. Course sizes ranged from 7 to 35

students enrolled. The courses covered a range of

topics in computer science including decision support

systems, system integration, data mining, web

technologies, operating systems, Java programming,

project management, and mobile applications Four of

the courses were at first year undergraduate level,

three at second year level and one at third year level.

116 students in total took part in the study,

answering at least one of the questionnaires. 108

students responded to the pre-study questionnaire, 72

students to the post-online class questionnaire, and 75

students to the post-study questionnaire.

Demographic information for the participants is

shown in Table 1. The age range of the participants

was surprisingly wide for undergraduate students (20

– 45 years), but 42 participants (41.0%) were 25 years

or younger. The sample had more women than men

(63.0% women, 37.0% men), although the overall

enrolment of women at SEU is 46.3% (2021/2022

figures, figures for 2022/2023 academic year not

available). This over representation of women in the

sample may be due

to the tendency of women to

volunteer for research more than men (Rosnow &

Rosenthal, 2012).

Table 1: Demographics of the participants.

Age

Range

Mean

Standard deviation

20 – 45 years

28.5

6.0

Gender

Men

Women

40 (37.0%)

68 (63.0%)

Level of Study

Year 1

Year 2

Year 3

32 (29.6%)

49 (45.4%)

27 (25.0%)

3.3 Online Questionnaires

Three questionnaires were developed and deployed in

the Qualtrics survey software (www.qualtrics.com): a

pre-study questionnaire, a post-class questionnaire,

and the post-study questionnaire. Questionnaires

The Role of Privacy and Security Concerns and Trust in Online Teaching: Experiences of Higher Education Students in the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia

69

comprised mainly 7-point Likert items, with some

multiple-choice and open-ended questions. Most of

the Likert item questions were mandatory, but the

open-ended questions were optional.

Pre-Study Questionnaire: measured students'

privacy and security concerns about online teaching

and their trust in different actors and entities in online

environments. This questionnaire included seven

previous questionnaires on online privacy, security

and trust in online teaching, adapted for use in the

current context:

- Privacy concerns in online teaching (11 items,

adapted from Peng & Dutta, 2022)

- Privacy concerns about instructors and

classmates during online teaching (3 items,

adapted from Kim, 2021)

- Security concerns in online teaching (4 items,

adapted Kim, 2021)

- Trust in the VLE (in this case, Blackboard) (6

items, adapted from Ejdys, 2018)

- Trust in the institution (7 items, adapted from

Ejdys, 2018)

- Trust in the instructor (5 items, adapted from

Cavanagh et al., 2018)

- Trust in classmates (5 items, adapted from Rice

& Schroeder, 2021).

A set of new items was also developed, these

measured:

- Privacy concerns about the student’s location

and personal space in online teaching classes (1

item)

- Concerns about the privacy of information in

online teaching situations (3 items).

This questionnaire also collected basic demographic

information about age, gender and year of study.

Post-Class Questionnaire: gathered information

about the use of webcams during online classes. At

the end of the online class, students were asked

whether they had their webcam on during the class

and their reasons for having the webcam on or not.

Post-Study Questionnaire: measured students’

frequency of having their webcam on during online

classes in general (plus a number of other questions,

not included in this paper, so details are not included

here).

The questionnaires were all developed in English

and then translated into Arabic with back translation

to check their accuracy.

A pilot study was conducted with five

undergraduate computer science students. They

completed all the questionnaires and were asked to

assess the clarity of the questions and the time

required to complete the questionnaire. A number of

small adjustments to the questionnaires were made as

a result.

The questionnaires are available from the authors

on request.

3.4 Procedure

The questionnaires were electronically delivered to

students through their SEU email addresses. To

optimize accessibility and engagement, this method

ensured that participants received the questionnaires

directly in their university email accounts. We also

encouraged participation by reminding all

participants to complete questionnaires. Participants

were given an information sheet about the aims of the

study and how their responses would be processed

and stored. In particular, participants were assured

that their individual responses would not be shared

with their instructors or the institution and that only

aggregate data would be shared or made public. The

study was conducted during weeks 10 and 11 of the

2023 Spring semester.

3.5 Data Analysis

The data collected included both quantitative and

qualitative data. The Likert item ratings were often

skewed towards the lower end of the scale, so non-

parametric statistical methods were used. The

Wilcoxon One Sample Signed Ranks Test was used

to investigate whether distributions of ratings differed

from the midpoint of the scale. As the sample size

exceeded 30 observations, the Z statistic for the

normal distribution approximation was used as an

extension of the Wilcoxon

test to compare different

ratings (Siegel & Castellan, 1988). Spearman’s non-

parametric correlations were used to investigate

relationships between groups of measures.

To analyse the large number of items measuring

online concerns about privacy and trust, Principal

Component Analysis (PCA) was used, grouping the

items by topic. Thus, one PCA was conducted on the

18 privacy items, and another on the 23 trust items.

As there were only four items on online security

concerns about online teaching, these were analysed

with Spearman non-parametric correlations, as this is

not enough items to conduct a PCA.

A linear regression was used to investigate

whether a range of measures could predict

participants’ self-reported frequency of webcam use

in online classes.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

70

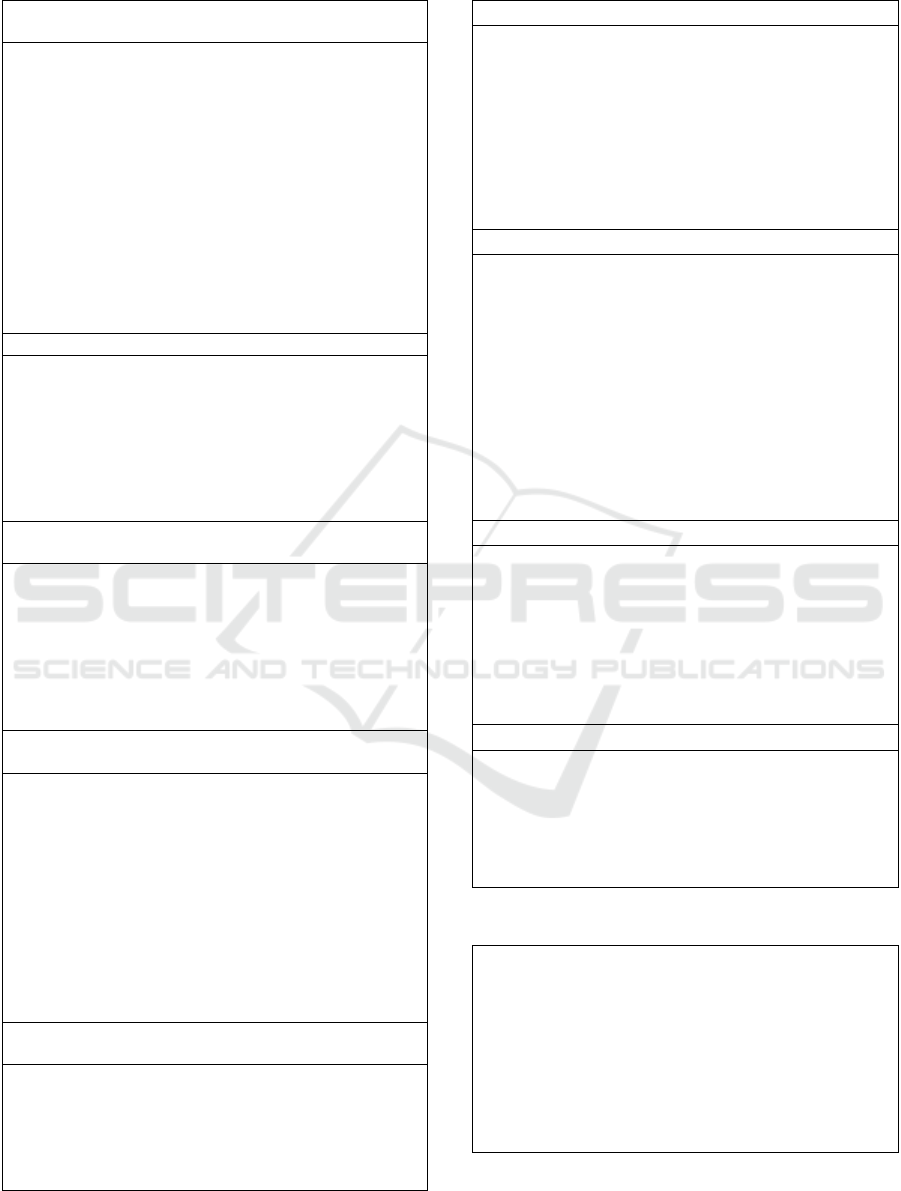

Table 2: PCA of privacy concerns about online teaching.

Component 1: Institutional use and protection of

students’ personal information

Universities should never sell students’ personal

information to another organization

Universities should not share students’ personal

information with other organizations unless it has been

authorised by the students

Universities should devote more time and effort to

preventing unauthorised access to students’ personal

information

Universities should prevent unauthorised people from

accessing students’ personal information without

considering the cost

Universities should take more measures to ensure that

unauthorised people cannot access students’ personal

information

Component 2: Information collection by institution

It bothers me when I am asked for personal information

during online teaching classes

I think for a while if I am asked to provide personal

information during online teaching classes

It bothers me to give personal information to so many

different courses for online teaching

It bothers me that so much personal information is

collected during online teaching courses

Component 3: Unauthorised information use by

instructors and classmates

I am concerned that another student will use my personal

information (e.g. captured facial images) without my

permission.

I am concerned that my personal information will be

leaked by another student against my will

I am concerned about my personal information (e.g. facial

expressions, physical appearance, etc.) being exposed

online

Component 4: Privacy during online

teaching (in relation to instructors and classmates)

I am not comfortable with my physical location and

personal space (e.g. my room, my whereabouts etc.)

being seen by other participants in online teaching classes

I am concerned that my instructor will use my

contribution to an online class (e.g. my work being used

as an example) without my permission.

I am concerned that my classmates will use my

contribution to an online session (e.g. my idea provided in

an online group discussion) without my permission.

Overall, I am concerned about my personal information

when participating in online class activities (e.g. online

group discussions)

Component 5: Unauthorised information use by

institution

Universities should never use students’ personal

information for any other purposes unless it has been

authorized by the individual student

When students give personal information during online

teaching classes for some particular reason, the university

should never use the information for any other purpose

Table 3: PCA of questions on trust in online teaching

Component 1: Trust in instructor

My instructor can be described as someone who listens

very carefully to me

It's important to my instructor to understand what my

educational goals are

My instructor understands me

My instructor accepts me for who I am

My instructor is careful not to dismiss my concerns

My instructor cares about my education

My instructor truly cares about my educational welfare

Component 2: Trust in institution

(Name of institution) takes care of its students

Graduates of (name of institution) have no problem

finding a job in their profession

(Name of institution) is well recognised by employers

in the labour market

(Name of institution) applies the principles of ethics

and social responsibility in its activities

(Name of institution) provides opportunities for

students’ personal development

(Name of institution) is recognised internationally

(Name of institution) uses new technology to improve

my studies and gain knowledge and skills

Component 3: Trust in classmates

Overall, the students in my (name of course) class are

very trustworthy

The students in my (name of course) class are friendly

I can rely on my (name of course) classmates

I trust that my (name of course) classmates will keep

my personal information confidential

We are usually considerate of one another’s feelings in

this (name of course) class

Component 4: Trust in VLE

(Name of VLE) guarantees the anonymity of users

In (name of VLE), I can express my opinion about

studies, subjects and instructors without any fear

(Name of VLE) ensures the security of my personal data

(Names of VLE) is efficient and always works reliably

I can rely on (name of VLE)

Table 4: Security concerns about online teaching.

I do not feel secure about the online teaching resources

and tools used in my online teaching classes.

I am concerned that online teaching resources and tools

will not implement appropriate security measures for my

protection.

I am concerned that hacking might occur during online

teaching classes which will lead to the disclosure of my

personal information.

I am concerned that online teaching resources

The Role of Privacy and Security Concerns and Trust in Online Teaching: Experiences of Higher Education Students in the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia

71

4 RESULTS

4.1 Initial Analysis of the Privacy,

Security and Trust Questions

108 participants answered the pre-study

questionnaire which presented the questions about

concerns about privacy and security in online

teaching and those about trust in different actors and

entities in online teaching. Separate PCAs were

conducted on the ratings of privacy concerns and

those of trust to investigate whether they formed

meaningful groups for the participants.

The PCA of the privacy concern questions

produced an optimal solution with five components

that accounted for 70.0% of the variance (see Table

2). The components were: Institutional use and

protection of students' personal information

(accounted for 24.5% of the variance); Information

collection by institution (21.8%); Unauthorised

information use by instructors and classmates

(9.1%); Privacy during online teaching (in relation to

instructors and classmates) (7.1%); and

Unauthorised information use by institution (6.5%).

The PCA of the trust questions produced an

optimal solution with four components that accounted

for 62.4% of the variance (see Table 3). The

components were: Trust in instructor (accounted for

26.4% of the variance); Trust in institution (15.7%);

Trust in classmates (11.4%); and Trust in VLE (8.9%).

For the four questions about security concerns

about online teaching all the questions correlated with

each other at p < 0.001 (Spearman non-parametric

correlations), so these were treated as one component,

Security concerns about online teaching.

4.2 Levels of Concern About Privacy

and Security and Trust in a Range

of Actors and Entities in Online

Teaching (RQ1)

To investigate participants’ levels of concern about

privacy in online teaching, their scores on each of the

components which emerged from the PCA were

calculated by taking the median of the relevant items.

The same procedure was followed for the ratings of

concerns about security and the level of trust in

different actors and entities in online teaching.

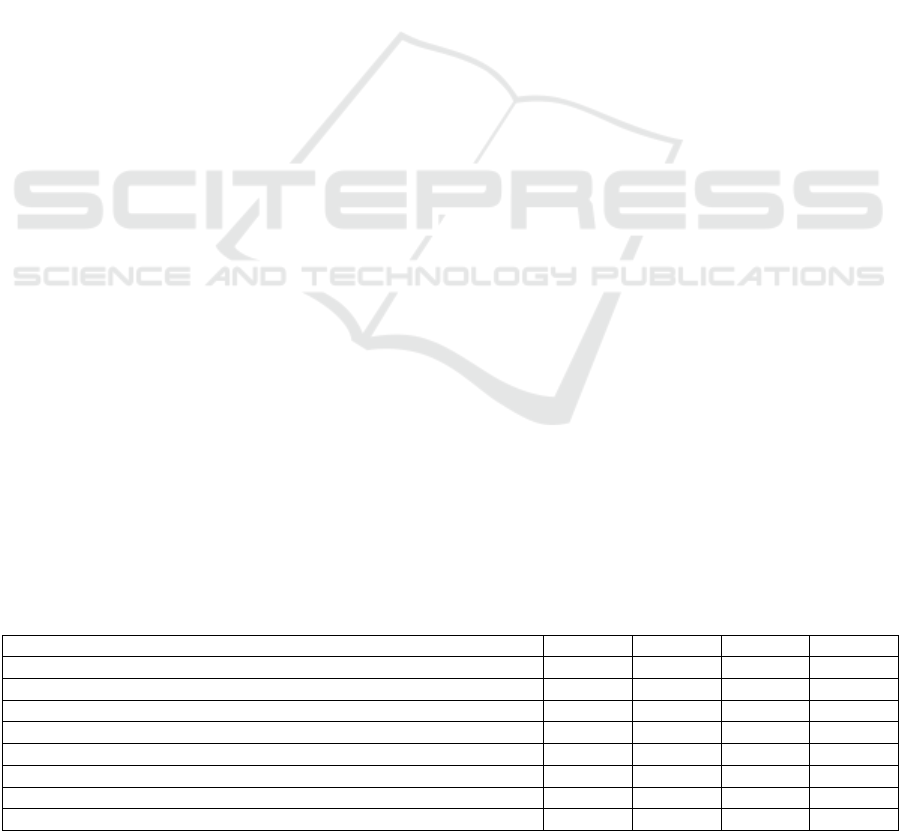

Participants’ scores on the five components of

concern about privacy in online teaching are given in

Table 5. Participants showed significantly high levels

of concern about Institutional use and protection of

students’ personal information, Information

collection by institution, and Unauthorised

information use by institution, but only moderate

levels of concern (not significantly different from the

midpoint of the scale

) about Unauthorised

information use by instructors and classmates and

Privacy during online teaching (in relation to

instructors and classmates). Thus, their privacy

concerns are related to their institution and the

information it might collect about them and how it

would use that information, but not their instructors

or their classmates to such an extent.

Participants’ scores on their Security concerns in

online teaching are also given in Table 5. These

scores did not differ significantly from the midpoint

on the scale, showing the participants had moderate

levels of concern about security in online teaching.

Finally, participants’ scores in their trust in

different actors and entities are given in Table 6.

These showed that participants had significantly high

levels of trust in their classmates and the VLE used

for online teaching (in their case the VLE was

Blackboard), moderate levels of trust in the institution

(the scores did not differ significantly from the

midpoint of the scale) and significantly low levels of

trust in their instructors.

4.3 Relationship Between Trust in

Different Actors and Entities, and

Security and Privacy Concerns in

Online Teaching (RQ2)

To investigate the possible relationships between

students’ trust in different actors and entities in online

Table 5: Levels of concern about privacy and security in online teaching.

Median SIQR Z p

Privacy concerns in online teaching …

Institutional use and protection of students’ personal information 7.00 0.00 9.40 <0.001

Unauthorised information use by institution 7.00 0.25 9.01 <0.001

Information collection by institution 5.25 1.13 4.49 <0.001

Privacy during online teaching (in relation to instructors and classmates) 4.75 1.35 1.74 n.s.

Unauthorised information use by instructors and classmates 4.50 2.09 1.39 n.s.

Security concerns in online teaching 4.00 2.00 0.55 n.s.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

72

Table 6: Students’ Trust in Different Actors.

Trust in .. Median SIQR Z p

Instructors 2.00 1.75 -4.49 < 0.001

Institution 4.00 1.25 1.47 n.s.

Classmates 6.00 1.50 5.51 < 0.001

VLE 6.00 1.50 5.83 < 0.001

Table 7: Correlations between privacy concerns and trust in different actors and entities in online teaching.

Instructors Institution Classmates VLE

Institutional use and protection of students’ personal

information

Information collection by institution

< 0.005

Unauthorised information use by instructors and classmates

Privacy during online

teaching (in relation to instructors and classmates)

< 0.005

< 0.05

neg

Unauthorised information use by institution

< 0.05 < 0.05

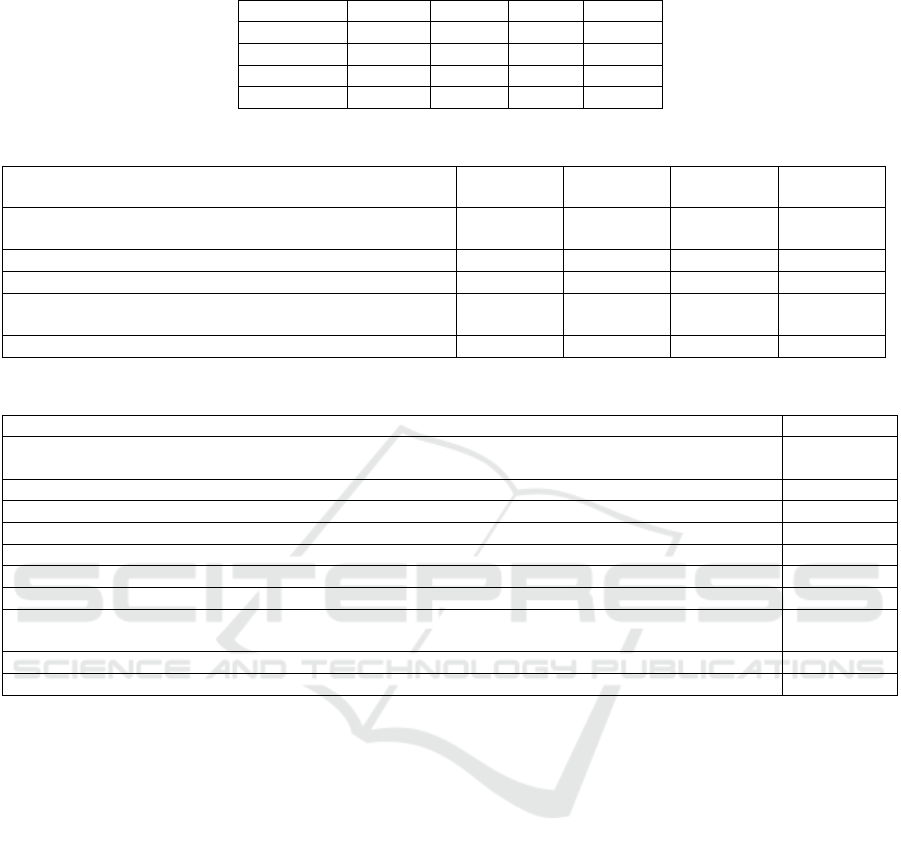

Table 8: Reasons why participants leave their webcam off during online classes (N = 58).

Reason N (%)

I am concerned if other students made recordings or screenshots without my permission (e.g., using their

camera phone)

34 (58.6%)

It makes me focus on how I look instead of the course content 32 (55.2%)

I do not know who can access recordings of online sessions or where they are stored 31 (53.4%)

It impairs my flexibility of where I can attend the session from (e.g., attending from a café) 29 (50.0%)

It makes it hard for me to conduct other activities during the class 28 (48.3%)

It makes it hard for me to move away from my computer 26 (44.8%)

It would distract other students 19 (32.8%)

I am concerned that online sessions might be hacked which will lead to disclosure of my personal

information

19 (32.8%)

It overloads the bandwidth I have 18 (31.0%)

I am concerned about my physical location being seen 13 (22.4%)

teaching and their online privacy concerns,

Spearman’s non-parametric correlations were

calculated between the components which emerged

from the PCA. Table 7 shows the pattern of

correlations. There was a significant positive

correlation between concerns about Information

collection by institution and Trust in institution. This

is a counter-intuitive direction for the correlation, as

one would expect that as trust in the institution

increases, concern about privacy issues related to

information collection by the institution would

decrease. But a strong positive correlation (p < 0.005)

was found. Thus, although some students may have

general trust in their institution, they still have

concerns about the information the institution is

collecting about them. Interestingly, there were no

other significant correlations between trust in the

institution and privacy concerns, for example there

was no correlation between trust in the institution and

the institution’s unauthorized use of information.

The was also a strong significant positive

correlation (p < 0.005) between Privacy during online

teaching (in relation to instructors and classmates)

and Trust in instructors. This direction of this

correlation is also counter-intuitive, as one would

expect that as trust in instructors increases, concern

about privacy during online teaching in relation to

instructors and classmates would decrease. As with

trust in the institution, there was no other significant

correlations, particularly between Trust in instructor

and Unauthorised information use by instructors and

classmates.

There was also a significant positive correlation

between Unauthorised use of information by

institution and Trust in VLE. This was another

correlation in the unexpected direction, although the

link between the institution and the VLE is not

necessarily clear. Do students see the VLE as

“belonging” to the institution or as an entirely

separate entity? This point needs further

investigation.

The Role of Privacy and Security Concerns and Trust in Online Teaching: Experiences of Higher Education Students in the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia

73

These counter-intuitive and unexpected

correlations suggest that trust in actors and entities in

online teaching is separate from possible privacy

concerns about them. This possibility clearly needs

further investigation.

Finally, there was a significant negative

correlation between Privacy during online teaching

(in relation to instructors and classmates) and Trust

in classmates. This is a correlation in the expected

direction, in that as trust in classmates increases,

privacy concerns decrease. It is interesting that this

expected relationship is with classmates, which may

suggest that because students know each other

personally, their perception of trust in their

classmates is of a different nature to their perception

of other, more remote and in some cases, abstract

actors and entities.

To investigate the possible relationships between

students’ trust in different actors in online teaching

and their online security concerns in online teaching,

Spearman’s non-parametric correlations were also

calculated between these components. There was no

significant correlation between Security concerns in

online teaching and trust in any of the different actors

and entities in online teaching. This result was also

quite unexpected.

4.4 Students’ Use of and Attitudes to

Webcams in Online Teaching

(RQ3)

At the end of one of the online classes during the two

week study period, 72 participants completed the

post-class questionnaire. One set of questions in this

questionnaire was about their webcam use in the

class. 58 participants (80.6%) reported having their

webcam off during the preceding online class, 14

(19.4%) reported that they did not remember whether

they had it on or off and none reported having it on.

In the post-study questionnaire, participants were

asked to rate how often they were turned on their

webcam during online classes in general (scored as

Never = 1 to Very frequently = 7). 67 participants

answered this question. They rated their frequency of

turning on their webcam as very low (median: 1.00,

SIQR: 0.50), the median was significantly below the

midpoint of the rating scale (Z = -6.85, p < .001).

Indeed, 47 (70.1%) of participants stated that they

never turned their webcam on, and only 20 (29.9%)

stated that they turned it on at least occasionally, with

only one participant stating that they turned it on all

the time.

In the post-class questionnaire participants were also

asked why they left their webcams off in online

classes in a multiple-choice question with a set of

options developed from previous research results.

Table 8 gives the frequency of responses (answered

by 58 participants). Two of the three most frequent

answers were about privacy and security of personal

information in online teaching, and mentioned by

more than half the participants: “I am concerned if

other students made recordings or screenshots

without my permission (e.g., using their camera

phone)” (mentioned by 34 participants, 58.6%) of

responding participants and “I do not know who can

access recordings of online sessions or where they are

stored” (mentioned by 31 participants, 53.4%).

Interestingly the first statement is about privacy and

security in relation to other students, whereas the

second is more about privacy and security in relation

to instructors and the institution. Also of note is that

fact that concern about the participant’s physical

location being seen, which we predicted would be a

prominent concern, was only chosen by less than a

quarter of participants (13, 22.4%).

4.5 Relationship Between Webcam Use

and Trust, Privacy and Security

Concerns in Online Teaching

(RQ4)

To investigate the relationship between participants’

webcam use and their trust in different actors and

entities and concerns about privacy and security in

online teaching, a linear regression was conducted to

predict their frequency of webcam use from the other

measures. Overall, there was no significant prediction

of frequency of webcam use from this set of predictor

variables (F

10, 57

= 1.75, n.s.). However, one

individual variable, Trust in instructors was a strong

predictor of frequency of webcam use (t = 2.76, p <

0.008). There was a positive relationship between

Trust in instructors and frequency of use of webcams.

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

This study explored the relationship between the

privacy and security concerns of HEI students in the

KSA in relation to online teaching, their level of trust

in the various actors and entities involved in online

teaching and the relationship between these variables.

In addition, it investigated their use of and attitudes to

webcams in online teaching and how their use of

webcams related to privacy and security concerns and

trust in various actors and entities.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

74

In relation to RQ1, participants showed high

levels of privacy concern about their institution, but

only moderate levels of concern about their

instructors and classmates and about security in

online teachers. This raises important questions about

how HEIs deal with the privacy of students’

information and how they communicate their policies

and actions in that area to students. The levels of trust

in actors and entities in online teaching also produced

interesting results, with high levels of trust in

classmates and the VLE, but low levels of trust in

instructors. Again, this raises important questions for

HEI instructors (and the institutions employing

them), as to why students appear not to trust them.

In relation to RQ2, the correlations between

privacy and security concerns among HEI students in

the KSA and their trust in various actors and entities

in online teaching revealed complex and somewhat

perplexing results. While there were a number of

significant correlations, they were not always the

ones we were predicting or more importantly in the

directions we were predicting, with increased

concerns about the institution and instructors aligned

with increased trust. This suggests that having a high

level of concern about privacy does not necessarily

mean a lack of trust; in fact, it may be associated with

a higher level of trust. Clearly the relationships

between these variables in online teaching needs

further investigation.

These finding are interesting in relation to issues

raised in the literature, which emphasise the

importance of transparent and responsible

information handling in fostering institutional trust

(Teng & Song, 2022). According to Anwar (2021)

institutions need to address privacy concerns and

exhibit ethical conduct to build and maintain trust,

reinforcing the significance of transparent data

practices. In addition, these finding are interesting in

relation to previous work of the impact of trust on

institutions and its influence on individuals' attitudes

towards information sharing (Nwebonyi et al. ,2022).

Ejdys (2018) also notes the significance of

institutional trust in the implementation, adaptation,

and use of new technologies, especially in the public

sector. This highlights the necessity to address not

only the technical functionality of digital

technologies but also the broader societal and ethical

implications, encompassing concerns about data

privacy and security.

The unexpected positive correlation between

privacy concerns during online teaching and trust in

instructors is also interesting. Contrary to

expectations, increased privacy concerns were

positively associated with higher levels of trust in

instructors. This finding does not align with the idea

that a positive instructor-student relationship,

extending beyond academic matters to include

personal understanding, respect, and a genuine

concern for the student's well-being and educational

success, contributes significantly to building trust in

instructors. This result raises questions about the role

of privacy perceptions in shaping interpersonal

relationships within online teaching.

In relation to RQ3, the fact that no participant

reported their webcam being during the online class

agrees with previous research from a number of

countries that students are very reluctant to have their

webcams on during online teaching (Almekhled &

Petrie 2023a; Bedenlier et al., 2021; Castelli &

Sarvary, 2021; Dixon & Syred, 2022; Gherheș et al.,

2021). Thus, Saudi students are no different in this

respect to students in other countries. The most

frequently mentioned reasons for not wanting the

webcam on related to privacy concerns about

personal information, which only partly aligns with

the ratings of privacy concerns in online teaching.

The most frequently mentioned reason was the

concern that other students would make recordings

without permission, but in the ratings, only moderate

levels of concern were expressed about other students

and instructors. It may be that when presented with a

specific scenario, participants did feel this was a

concern. However, there was good alignment

between the reason for not having the webcam on,

which was that participants did not know who could

access the recordings or where they are stored with

the high levels of concern about institutional use and

unauthorised use of students’ information. These

results highlight the fact that the way questions are

worded may affect the outcome, as well as the

complex relationships between these variables.

In relation to RQ4, only Trust in instructors was

a significant predictor of participants’ self-reported

frequency of having their webcam on during online

classes. This makes sense as a finding, and the low

levels of trust in instructors may be a further reason

for not having the webcam on. In this study,

instructors also did not have their webcams on (this is

typical in this institution) and it would be very

interesting to explore whether if instructors had their

webcams on, would that increase trust and encourage

students to have theirs on as well.

The study had a number of limitations which need

addressing. The first is related to the cultural and

linguistic context. All the questionnaires used in the

research were translated into Arabic from English due

to the absence of prior validation with Saudi

participants. The original validation of these

The Role of Privacy and Security Concerns and Trust in Online Teaching: Experiences of Higher Education Students in the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia

75

instruments was conducted with samples from North

America, Europe, and East Asia, so their validity for

the Saudi context is not established.

Secondly, the results relied on the honesty and

accuracy of the participants’ self-reports. Because the

study is about online teaching and participants were

assured that their individual responses would not be

shared with their instructors or the institution,

however they may still have been hesitant to answer

completely frankly on certain questions. But even if

participants are trying to be honest, it may have been

difficult to be accurate to answer in terms of largely

rating items. Triangulation with other research

methods such as interviews and logging actual

behaviour (which may in itself raise serious ethical

issues) is clearly need to explore the issues further.

Thirdly, in an effort to not overburden participants

with too many time-consuming questions, wherever

possible, rating items and multiple-choice options

were used. In retrospect, it many have been preferable

to include a greater number of open-ended questions.

Particularly on the issue of why participants did not

have their webcam on during online classes, although

we based the multiple-choice options on reasons

found in previous research, this may have primed the

participants, and an open-ended question would have

been better for that issue.

As highlighted in the Introduction, our study

focused on KSA students enrolled in Saudi HEIs. It is

important to acknowledge that the concerns and

behaviour of students in other countries are likely to

differ. However, our research complements research

conducted in a range of other countries and expands

the variables considered in relation to students’

concerns about online teaching.

In conclusion, our research makes a contribution

to the existing body of research on privacy and

security concerns and trust in different actors and

entities in online teaching. The findings offer

questions for future investigations, to further

investigate the specific factors influencing students’

concerns and trust in this area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Saudi Electronic

University for their support in conducting this

research, as well as the instructors and students who

participated. This research is part of the PhD

programme for the first author which is funded by the

Saudi Electronic University.

REFERENCES

Aldheleai, H. F., Bokhari, M. U., & Hamatta, H. S. A.

(2015). User security in an e-learning system. In

Proceedings of 2015 Fifth International Conference on

Communication Systems and Network Technologies

(pp. 113). doi: 10.1109/CSNT.2015.113.

Almekhled, B., & Petrie, H. (2023a). Concerns of Saudi

higher education students about the security and

privacy of online digital technologies during the

coronavirus pandemic. In Proceedings of 19th

International Conference of Technical Committee 13

(Human-Computer Interaction) of IFIP (International

Federation for Information Processing).

Almekhled, B., & Petrie, H. (2023b). Privacy and security

in online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic:

experiences and concerns of teachers in UK higher

education. In Proceedings of 36th International BCS

Human-Computer Interaction Conference.

Anwar, M., & Greer, J. (2012). Facilitating trust in privacy-

preserving e-learning environments. IEEE

Transactions on Learning Technologies, 5(1), 62–73.

Bedenlier, S., Wunder, I., Glaser-Zikuda, M., Kammerl, R.,

Kopp, B., Ziegler, A., Handel, M. (2021). Generation

invisible?: Higher education students’ (non)use of

webcams in synchronous online learning. International

Journal of Educational Research Open, 2, 100068

Booth, M. (2012). Boundaries and student self-disclosure in

authentic, integrated learning activities and

assignments. New Directions for Teaching and

Learning, 131, 5–14.

Briggs, P., Simpson, B., & Angeli, A. D. (2004).

Personalisation and trust: A reciprocal relationship? In

C. Karat, J. O. Blom, & J. Karat (Eds.), Designing

personalized user experiences in eCommerce (pp. 39–

55). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Buchanan, T., Paine, C., Joinson, A. N., & Reips, U.-D.

(2007). Development of measures of online privacy

concerns and protection for use on the Internet. Journal

of the American Society for Information Science and

Technology, 58(2), 157–165.

Castelli, F. R., & Sarvary, M. A. (2021). Why students do

not turn on their video cameras during online classes

and an equitable and inclusive plan to encourage them

to do so. Ecology and Evolution, 11(8), 3565-3576.

Cavanagh, A. J., Chen, X., Bathgate, M., Frederick, J.,

Hanauer, D. I., & Graham, M. J. (2018). Trust, growth

mindset, and student commitment to active learning in

a college science course. CBE Life Sciences Education,

17(1), ar10. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-06-0107.

Dixon, M., & Syred, K. (2022). Factors Influencing student

engagement in online synchronous teaching sessions:

Student perceptions of using microphones, video,

screen-share, and chat. In Proceedings of the 9th

International Conference, LCT 2022, Held as Part of

the 24th HCI International Conference, HCII 2022,

Virtual Event, June 26 – July 1, 2022, Proceedings,

Part I (pp. 209–227).

Ejdys, J. (2018). Building technology trust in ICT

application at a university. International Journal of

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

76

Emerging Markets, 13(5), 980-997.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-07-2017-0234.

Fukuyama, F. (1996). Trust: Social virtues and the creation

of prosperity. Simon and Schuster.

Gherheş, V., Simon, S., & Para, I. (2021). Analysing

students’ reasons for keeping their webcams on or off

during online classes. Sustainability, 13, 3203.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063203.

Giesbers, B., Rienties, B., Tempelaar, D., & Gijselaers, W.

(2013). Investigating the relations between motivation,

tool use, participation, and performance in an e-learning

course using web-videoconferencing. Computers in

Human Behavior, 29(1), 285–292.

Gillies, D. (2008). Student perspectives on

videoconferencing in teacher education at a distance.

Distance Education, 29(1), 107–118.

Grandison, T., & Sloman, M. (2000). A survey of trust in

Internet applications. IEEE Communications Surveys &

Tutorials, 3(4), 2–16.

Joinson, A. N., & Paine, C. (2006). Self-disclosure, privacy

and the Internet. In A. Joinson, K. McKenna, T.

Postmes, & U.-D. Reips (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook

of Internet Psychology (pp. 237–252). Oxford, United

Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Kim, S. S. (2021). Motivators and concerns for real-time

online classes: focused on the security and privacy

issues. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(4),

1875-1888.

Kularski, C. M., & Martin, F. (2021). Online student

privacy in higher education: A systematic review of the

research. American Journal of Distance Education,

36(3), 227–241.

Liu, Z., Wang, X., Min, Q., & Li, W. (2018). The effect of

role conflict on self-disclosure in social network sites:

An integrated perspective of boundary regulation and

dual process model. Information Systems Journal,

29(2), 279-316.

Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust and Power. Chichester: Wiley.

Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Agarwal, J. (2004). Internet

users’ information privacy concerns (quips): The

construct, the scale, and a causal model. Information

Systems Research, 15(4), 336–355.

Martin, K. (2016). Understanding privacy online:

Development of a social contract approach to privacy.

Journal of Business Ethics, 137(3), 551–569.

McEvily, B., Perrone, V., & Zaheer, A. (2003). Trust as an

organizing principle. Organisation Science, 14(1), 91-

103.

Misztal, B. (1996). Trust in modern societies: The search

for the bases of social order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Pallof, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2007). Building online learning

communities: Effective strategies for the virtual

classroom. John Wiley & Sons.

Patil, S., & Kobsa, A. (2005). Privacy in collaboration:

Managing impression. In Proceedings of the First

International Conference on Online Communities and

Social Computing, Las Vegas, NV, 2005.

Peng, M.-H., & Dutta, B. (2022). Impact of personality

traits and information privacy concern on E-Learning

environment adoption during COVID-19 pandemic: An

empirical investigation. Sustainability, 14, 8031.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138031

Petchamé, J., Iriondo, I., & Azanza, G. (2022). “Seeing and

Being Seen” or just “Seeing” in a smart classroom

context when videoconferencing: A user experience-

based qualitative research on the use of cameras.

International Journal of Environmental Research and

Public Health, 19(15), 9615.

Rice, V. J., & Schroeder, P. J. (2021). In-person and virtual

world mindfulness training: Trust, satisfaction, and

learning. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social

Networking, 24(8), 526–535.

Rosnow, R. L., & Rosenthal, R. (2012). Beginning

Behavioral Research: A Conceptual Primer (7th

edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice

Hall.

Salmon G., Ross B., Pechenkina E., & Chase A.-M. (2015).

The space for social media in structured online learning.

Research in Learning Technology, 23, 28507

http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v23.28507.

Siegel, S., & Castellan, N. J. (1988). Nonparametric

statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill.

Smith, H. J., Dinev, T., & Xu, H. (2011). Information

privacy research: An interdisciplinary review. MIS

Quarterly, 35(4), 989–1015.

Smith, H. J., Milburg, S. J., & Burke, S. J. (1996).

Information privacy: Measuring individuals’ concerns

about organizational practices. MIS Quarterly, 20, 167–

196.

Steel, J. L. (1991). Interpersonal correlates of trust and self-

disclosure. Psychological Reports, 68, 1319–1320.

Teng, Y., & Song, Y. (2022). Beyond legislation and

technological design: The importance and implications

of institutional trust for privacy issues of digital contact

tracing. Frontiers in Digital Health, 4, 916809.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.916809

Tierney, W. (2006). Trust and the public good. New York:

Peter Lang.

Van Houtte, M. (2007). Exploring teacher trust in

technical/vocational secondary schools. Teaching and

Teacher Education, 23, 826-839.

Zhang, D., & Nunamaker, J. F. (2003). Powering e-learning

in the new millennium: an overview of e-learning and

enabling technology. Information Systems Frontiers,

5(2), 207-218.

The Role of Privacy and Security Concerns and Trust in Online Teaching: Experiences of Higher Education Students in the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia

77