TransLaboration: An Online Collaborative Learning Environment

with Socially Shared Regulation Prompts in Translation Classroom

Li Nanzhe

1,2 a

and Nurbiha A. Shukor

1b

1

School of Education, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310 Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia

2

School of Foreign Languages for International Business, Hebei Finance University,

3188 Hengxiang North Street, Baoding, China

Keywords: Online Collaborative Learning Environment, ADDIE Model, Socially Shared Regulation Learning Prompt,

Translation Learning.

Abstract: Online collaborative learning (OCL) has been widely used in various disciplines including translation subject.

Effective OCL needs the support of the OCL environment and pedagogical methods. Socially shared

regulation (SSR) is a useful strategy to improve OCL because it stimulates students’ participation. In learning

translation, OCL is usually adopted but students struggle with regulating their learning to reach consensus

about their translation work. This paper presents a new OCL environment, TransLaboration, to support

collaborative translation learning. In TransLaboration, SSR prompts are embedded to facilitate students’

social interaction, Moodle is used as the LMS, Tencent QQ works for students’ chatroom and Kingsoft

Document is applied as the workplace for collaborative translation. The design of TransLaboration and

learning activities are presented in this paper, and further investigation is needed to maximize its function.

1 INTRODUCTION

Online collaborative learning (OCL) is a pedagogical

approach involving students working in groups to

achieve common learning objectives using online

tools and environment (Ng et al., 2022). OCL is

regarded to be an effective way to promote students’

knowledge construction and cognitive development,

as well as foster students’ sense of community and

belonging among learners and has been widely

adopted in various educational contexts and different

subject domains (Oyarzun & Martin, 2023).

OCL supplies the space and time for students to

work together on learning tasks where they discuss

and analyse with critical discourse, provide food for

thought, argue with each other from different

perspectives, and reflect on the collaborative job.

Therefore, OCL emphasizes the active and

collaborative construction of knowledge through

social interaction and negotiation (Picciano, 2021)

However, OCL is faced with some challenges and

limitations that hinder the effectiveness and quality of

collaborative learning. For example, students may

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9625-2576

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9587-8929

encounter difficulties in participating in effective

interaction, managing time, resolving conflicts, and

coordinating group dynamics (Oyarzun & Martin,

2023; Robinson et al., 2017). Therefore, it is

important to design and evaluate OCL environments

that can support students’ and teachers’ needs and

expectations. Therefore, the design of a good OCL

environment has been a research concern (Johler,

2022).

OCL environment facilitates OCL by providing

various functions that enhance the OCL process, such

as Chatroom, uploading learning materials,

whiteboard, file sharing, annotating, feedback and

assessment, and by mediating the OCL activities

(Robinson et al., 2017).

Regulation of the learning process is an important

factor affecting OCL, and successful OCL needs

socially shared regulation (SSR) (Borge et al., 2022).

In SSR, group members collectively set goals, make

plans, monitor collaborative learning, and evaluate

and reflect on the learning process (Järvelä et al.,

2013). They continuously adjust their cognition,

metacognition, emotion, motivation, behaviour, etc.,

Nanzhe, L. and Shukor, N.

TransLaboration: An Online Collaborative Learning Environment with Socially Shared Regulation Prompts in Translation Classroom.

DOI: 10.5220/0012618200003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 363-370

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

363

in OCL process so as to complete the learning task

together (Isohätälä et al., 2017).

Socially shared regulation of learning is proven

useful to improve students’ knowledge construction

(Chen et al., 2019; Grau & Whitebread, 2012), group

performance (Panadero & Järvelä, 2015) and problem

solving (Hurme et al., 2009; Panadero et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, SSR is difficult to achieve because

group members possess different previous

experiences and regulatory strategies. They may not

be aware of the opportunity for SSRL or lack the

motivation to regulate collectively even if the

collaborative learning tasks are pedagogically

designed (Järvelä et al., 2014; Malmberg et al., 2015).

Learners’ SSR levels could only be improved with the

engagement of regulation prompts (Järvelä et al.,

2016).

Translation, as a complex cognitive and linguistic

activity, involves the conversion of two languages,

cultures and thinking modes (Li, 2018). Translation

education can benefit from OCL because

collaboration is also crucial for learning translation,

as it enables translation learners to theorise and test

hypotheses, transmit translation knowledge, utilise

better translation strategies, get real-life translation

experience, gain improvement in translation

competence and achieve optimum translation results

(Al-Shehari, 2017; Moghaddas & Khoshsaligheh,

2019).

However, to work collaboratively in a translation

classroom, students need such support as the

coordination strategy (Barros, 2011), task assignment

(Bayraktar Özer & Hastürkoğlu, 2020), time

management and collective problem-solving (Amini

et al., 2022) which could be addressed with the help

of SSR. However, no research has been conducted on

the effect of SSR in translation learning.

Based on this background, this paper presents a

new OCL environment, TransLaboration, aiming to

facilitate translation learning in higher education.

TransLaboration comprises a Moodle LMS, a

Chatroom and a co-authoring system. SSR prompts is

embedded in TransLaboration to ensure meaningful

collaboration. The development of TransLaboration

and the corresponding learning activities will be

presented and discussed in this paper.

2 METHODOLOGY

This study applied ADDIE instructional system

design model to develop the OCL environment. The

ADDIE model has been verified and widely used to

create a learning environment (Johnson-Barlow &

Lehnen, 2021; Muruganantham, 2015). The model

boasts an agile, iterative design process, which means

that each step during development can be revised and

improved. As such, errors can be fixed, and the

learning environment can be optimized on time

(Drljača et al., 2017).

2.1 The Translaboration Online

Collaborative Learning

Environment

The TransLaboration OCL environment aims to

facilitate English-major undergraduates to foster

translation competence in the translation classroom.

Based on ADDIE model, the development of

TransLaboration goes through five phases: analysis,

design, development, implementation, and

evaluation. These phases are interrelated and

sometimes overlap. In each phase, tasks and outputs

are set as guidelines to ensure the successful

development of the OCL environment (Spatioti et al.,

2022).

2.1.1 Analysis

Analysis phase aims to assess the needs of

TransLaboration OCL environment. Firstly, the

learning objective for designing TransLaboration is

to foster skills in translating text with the guidance of

socially shared regulation (SSR) prompts.

Next, the target learners’ profile was identified

based on their background and previously acquired

knowledge. The learners are second-year English

major students in a Chinese public university. They

take the translation class and already understand the

theoretical issues of translation. However, they need

to improve their translation practice skills. Besides,

they have Internet access and have experience in

using OCL environments.

These characteristics were considered when

setting SSR prompts in the TransLaboration and

assigning the group work according to the

pedagogical considerations based on Vygotsky

(1978)’s social constructivist learning theory and

Hadwin et al. (2011)’s SSR theory.

Following the above analysis, TransLaboration

consists of three components: the Learning

Management System (LMS), the online synchronous

discussion tool, and the online co-authoring platform.

Moodle is used as the LMS to set the OCL

environment with SSR prompts because it integrates

three central learning system components: the

learning strategy, learning material and learning

media (Gamage et al., 2022). Students obtain learning

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

364

tasks, SSR prompts and submit the group work in

Moodle.

Tencent QQ (QQ) is applied as the online

synchronous discussion tool. TransLaboration uses

QQ rather than Moodle Chatroom for the following

reasons. Firstly, QQ is independent of Moodle, which

means that students can simultaneously discuss in QQ

and refer to Moodle for task specifications and SSR

prompts. If students use Moodle Chatroom, they have

to log out of the Chatroom to check the learning

materials, which would interrupt the discussion.

Secondly, compared with Moodle Chatroom, Tencent

QQ provides functions such as capturing, annotating

and sending screenshots, which were necessary to

discuss translation tasks in this study.

Kingsoft Document (KDoc), an online co-

authoring platform, is used to edit the translated text

collaboratively online. Group members could log in

to Kingsoft Document and edit the translation while

checking the SSR prompts and other learning

materials in Moodle and discuss via Tencent QQ.

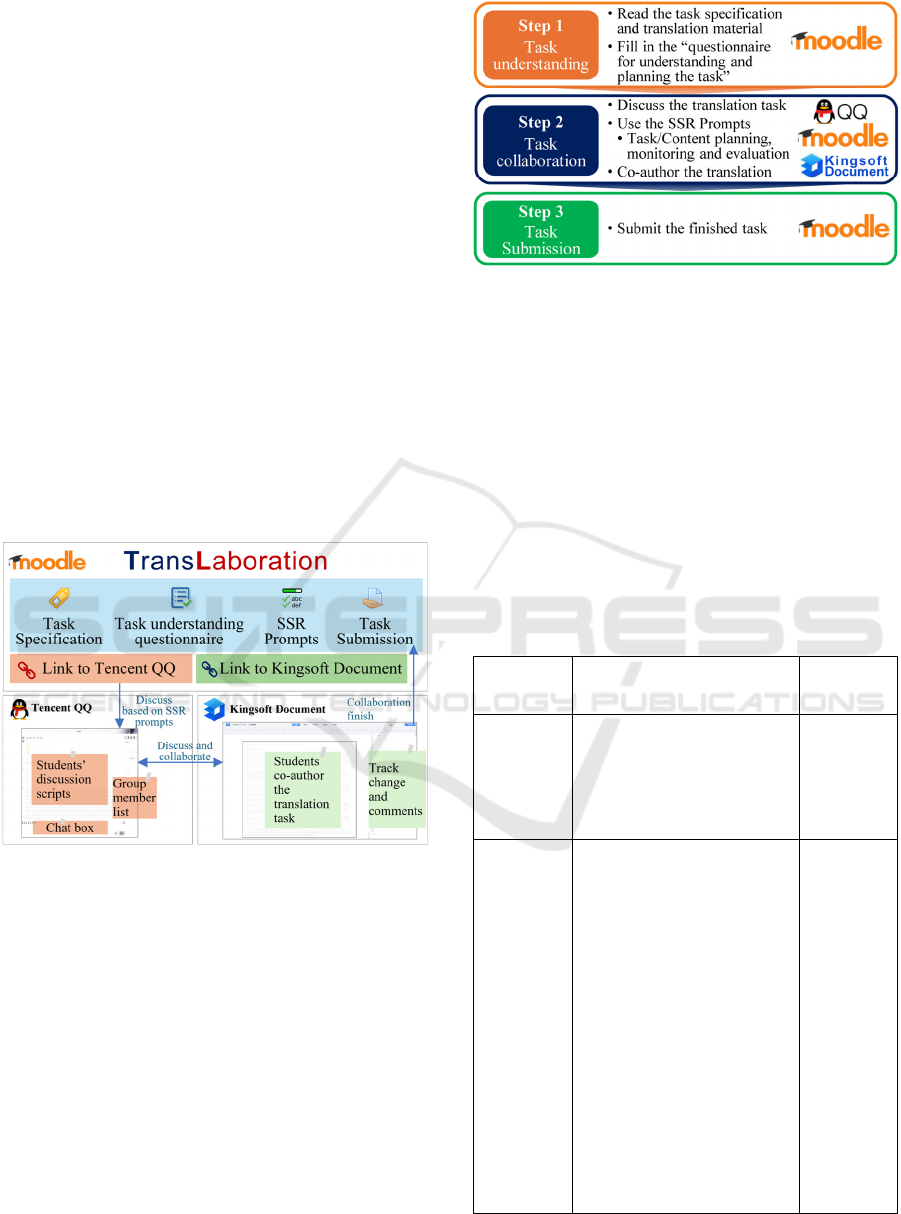

Figure 1 illustrates the working space for

TransLaboration.

Figure 1: Working space for TransLaboration.

2.1.2 Design

Design phase aims to create a framework for

collaborative learning activities. Figure 2 illustrates

the flow chart of the using TransLaboration in

translation learning.

The learning activities go through three steps. In

Step 1, students read the task specification to

understand the learning task and make a preliminary

plan individually. They are required to read the task

specification, translation materials, and fill in the

“questionnaire for individual task understanding and

planning” to help arouse their prior knowledge and

understand the learning task to facilitate their group

discussion. Step 1 is finished in the Moodle platform.

Figure 2: Design of learning step.

In step 2, students engage in group discussion via

QQ and edit the translation together in KDoc. During

the discussion, group members should refer to the

SSR prompts embedded in TransLaboration.

The design of SSR prompts is based on six SSR

strategies – task planning, content planning, task

monitoring, content monitoring, task evaluation and

content evaluation – aiming to prompt students to set

group goals, make a group plan, monitor and evaluate

the task progress and learning contents during the

collaboration procedures. Table 1 shows the design of

SSR prompts during the group discussion.

Table 1: Design of SSR prompts during the collaboration.

Procedures SSR prompts

SSR

Strategies

1.

Set group

goal

Please consider the task

requirement.

Please set a specific goal

rather than a general goal.

Please consider whether

the

g

oal is feasible.

Task

planning

2.

Make

group plan

Please consider the group

goal.

Please allocate the time

and subtasks.

Please assign roles for

group members.

Please consider the

resources you may use to

complete the task.

Please consider the

translation theories you

may use to complete the

task (e.g. translation

standards, strategies,

methods and skills).

Please consider whether

the plan is feasible.

Task

planning

Content

planning

TransLaboration: An Online Collaborative Learning Environment with Socially Shared Regulation Prompts in Translation Classroom

365

Table 1: Design of SSR prompts during the collaboration

(cont.).

Procedures SSR prompts

SSR

Strategies

3.

Finish

transla-

tion task

in group

Please check the time.

Please verify the progress

of the completion of the

task.

Please check for the

accurate use of translation

theories (e.g. translation

standards, strategies,

methods and skills).

Please provide a reason to

support your idea.

Task

monitoring

Content

monitoring

4.

Evaluate

group

work

Please check whether your

group completed all the

task requirements.

Please check whether your

group met the initial goal.

Please reflect on whether

your group applied

translation theories to

guide translation practice.

Please reflect on the

strategies your group used

to solve problems.

Please summarize gains

and weaknesses.

Please rate your group’s

final product.

Task

evaluation

Content

evaluation

In step 3, after evaluating the group work,

students submit their translation works to the OCL

environment through Moodle.

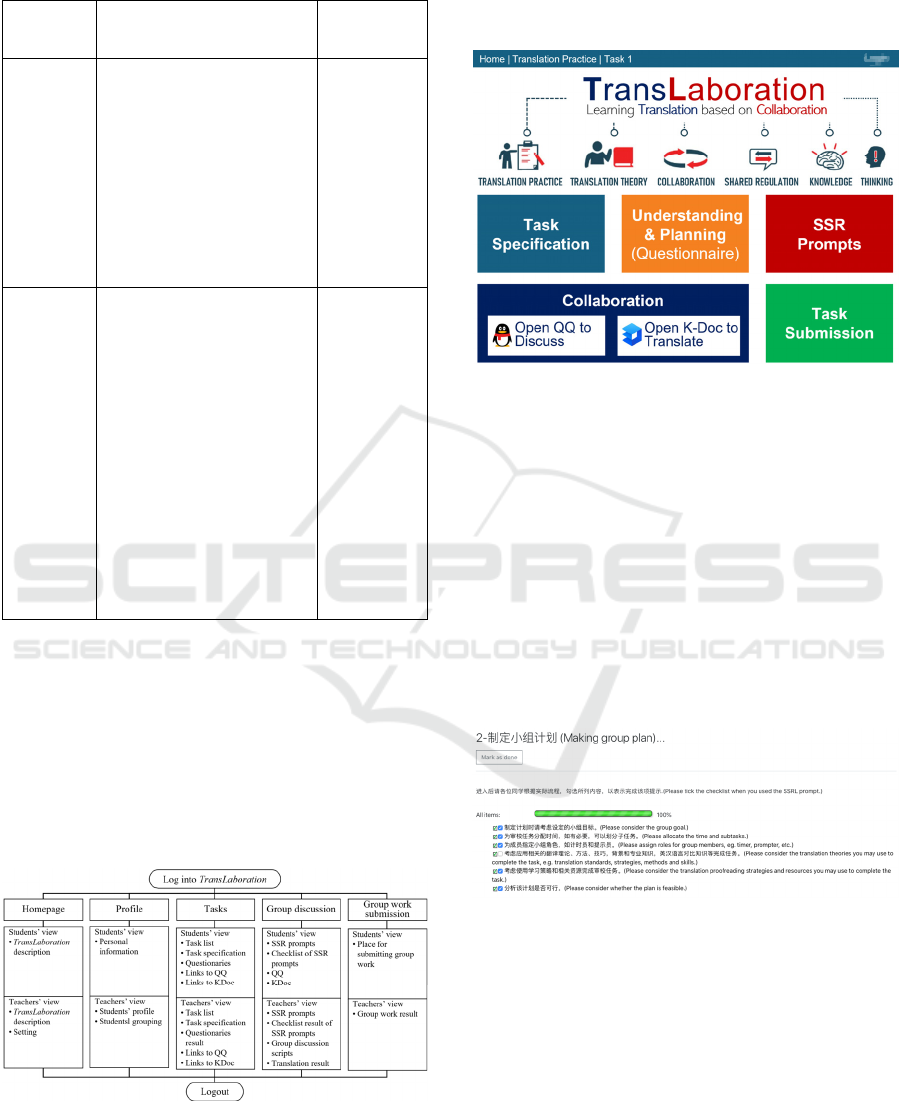

2.1.3 Development

TransLaboration

OCL environment is developed based

on the information gathered in the analysis and design

phase. The architecture of

TransLaboration

is shown as

Figure 3.

Figure 3: Architecture of TransLaboration.

To make

TransLaboration user-friendly, the user interface

is

simple and clear, as shown in Figure 4. In the

learning task webpage, appealing colours are used to

draw students’ attention. The buttons are set based on

the learning steps. As such, students only need to

click the button and finish the task step by step.

Figure 4: Screenshot of learning task portal in

TransLaboration.

To facilitate students using SSR prompts in the

group discussion, SSR prompts are set along the

sequential order of the tasks and embedded in

TransLaboration (as shown in Table 1). SSR prompts

are shown with a checklist to remind the group

members of each other’s progress and promote their

group awareness and regulation (Hadwin et al., 2011).

Students are asked to tick the checklist after using the

SSRL prompt item. If they have applied all the items,

100% is shown. As an example, Figure 5 illustrates

the checklist for SSR prompts when making the group

plan.

Figure 5: Checklist for SSR prompts (The contents are the

same with SSR prompts in Procedure 2. Make group plan).

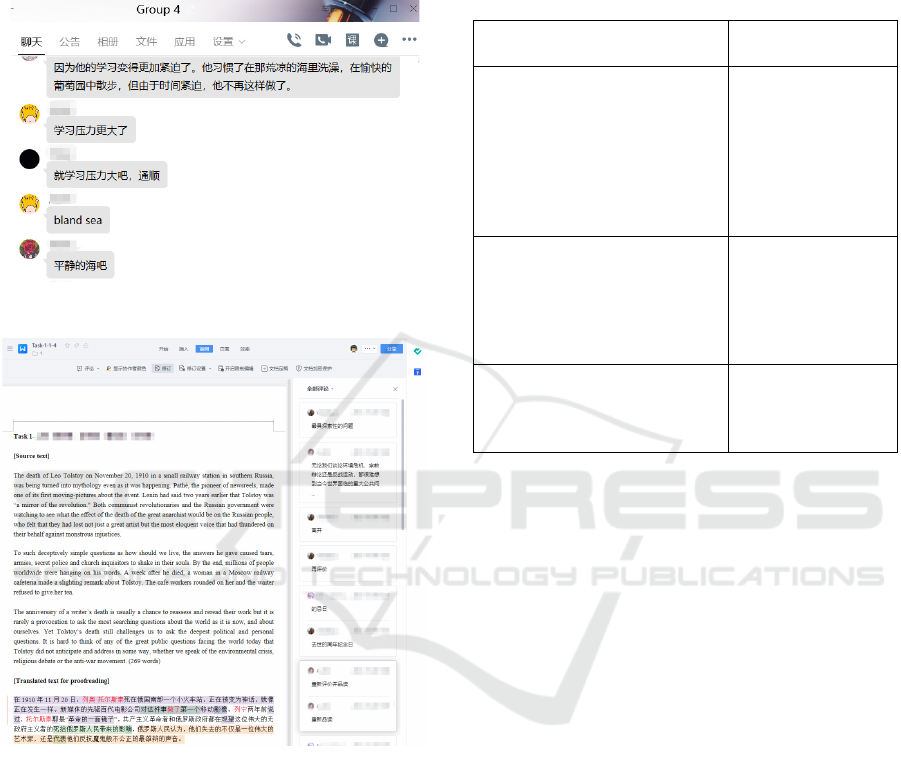

The function and interface of

TransLaboration

are

designed to facilitate students’ group work. Students

discuss in separate groups via QQ chatroom, meaning

that each group member could only see their own

group members, and others were invisible. In this

case, their discussion would not be disturbed by other

groups. Figure 6 shows students’ discussion in QQ

chatroom.

Students edit the translation together in KDoc,

while while discussing via QQ. KDoc could be

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

366

accessed directly through a link from the learning task

portal. During the collaboration, each group

member’s version is tracked, facilitating their

interaction and evaluation. Figure 7 illustrates

students co-author the translation in Kdoc.

Figure 6: Students discuss in QQ Chatroom.

Figure 7: Students co-author the translation task

collaboratively in KDoc.

2.1.4 Implementation

User test is carried out before the implementation of

actual learning activity to ensure the functionality and

integrity of TransLaboration. The OCL environment

is tested by 20 students. All the participants were

informed of the consent. They work in groups of 4

members and are given a sample translation task,

aiming to test the usability of task specification,

questionnaire, SSR prompts, online Chatroom,

translation practice collaboration and group work

submission. Their comments and suggestions are

used to improve the design and functionality of

TransLaboration. Table 2 shows the feedback from

the students in the pilot study and the corresponding

improvement.

Table 2: Examples of feedback from the students in the user

test and the corresponding improvement.

Feedback Improvement

“Moodle Chatroom is not user-

friendly. We neet to discuss

while reading the SSR prompts.

We have to log in and log out of

the Chatroom from time to

time. It is distractive and

reduces our efficiency.”

Tencent QQ was

used to replace

Moodle Chatroom

because Moodle log

files were not used

in this study.

“It will be more convenient if

we can go to Kingsoft

Document directly from a

button with our group number.”

The URL links to

Kingsoft groups

were redesigned as

a button with the

group number in it.

“When I do not know what to

do next, I check the SSR

prompts and have an idea.”

-

2.1.5 Evaluation

Expert evaluations are carried out to correct the errors

and improve the functionality of TransLaboration.

The evaluation phase comprises two parts: formative

and summative evaluation.

The formative evaluation is ongoing between

development phases to correct the errors and improve

the functionality of TransLaboration. In the analysis,

design and development phases, all the task

information, learning objectives, learning content,

learning strategy and prototype of the learning

environment are evaluated and revised by experts.

For example, in the design phase, the consistency of

SSR theory and SSR prompts used for the online

collaborative learning environment was validated by

an expert, and revisions were made before moving to

the development phase.

The summative evaluation is conducted after the

completion of TransLaboration along with the user

test. Education technology experts and teachers are

invited to validate the effectiveness and efficiency of

TransLaboration, especially whether the learning

activities align with the learning objectives. Table 3

shows the comments from the expert validation.

TransLaboration: An Online Collaborative Learning Environment with Socially Shared Regulation Prompts in Translation Classroom

367

Table 3: Expert validation of online learning tasks and

environment.

Expert Position/Qualification/

Working Experience

General comments

A Teacher/PhD in

Translation Studies/14

years

The tasks are

generally good for

translation practice.

B Associate Professor in

Computer

Science/Software

engineer/15 years

The online learning

system is tested and

suitable for this

study.

C Teacher/PhD in

Educational

Technology/15 years

The online learning

activity is suitable

and the SSR Prompts

are good to go.

2.2 Collaborative Learning Task

TransLaboration is developed to improve students’

practical translation skills in the translation

classroom. Following the collaborative translation

task design in previous studies (Pitkäsalo & Ketola,

2018; Turiman et al., 2023), the learning tasks in

TransLaboration go through three procedures: a.

identify the source text, b. translating the text, and c.

submit the translated text. The three procedures are

clearly structured in TransLaboration.

In terms of the types of CL tasks,

TransLaboration supports translation tasks and

translation post-editing tasks depending on the

learning materials uploaded to the co-authoring

system. For translation tasks, the co-authoring system

only contains the source text, and for translation post-

editing tasks, the co-authoring system contains both

the source text and the initially translated text (with

errors). Students read the learning materials, make

analyses, and input or edit the translation collectively.

To promote students’ collaboration,

TransLaboration embeds SSR prompts (See Table 1)

that guide group members to collectively understand,

proceed, and reflect on the collaborative translation

tasks. As such, the design of SSR prompts focuses on

prompting the discussion regarding both the task

content, such as checking for the appropriate use of

translation skills, and the task process, such as

checking for compliance with task instructions.

Meaningful discussion is one of the preconditions

for the success of collaborative translation (Tekwa,

2023). Pedagogically, to promote students’

discussion and collaboration, before collaboration,

students are required to finish the “Questionnaire for

task understanding and planning”, which guides them

to understand the learning task and make preparation

for the coming group work.

During the group work, one group member can be

assigned as the prompter to help activate the SSR

prompts in a timely manner and ensure that all the

group members are engaged in meaningful discussion.

Besides, during the collaborative translation tasks,

students may use such functions as track-change,

comments, and screenshot capture, which are all

included in TransLaboration. For example, students

may capture a website’s screenshot to support their

translation; They may need to revert to a previous

translation version through track-change; and they

may use the comments when doing the peer review.

3 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

This paper aims to introduce TransLaboration, an

OCL environment for undergraduate students in the

translation classroom. The OCL environment breaks

down the limitations of time and space in

collaborative learning and provides students with

more opportunities to internalize socially constructed

knowledge (Smith, 2017). The key to successful OCL

is to ensure that group members share information in

the learning group (Johler, 2022). Nevertheless,

merely situating students in an OCL environment and

assigning the group task does not necessarily result in

effective learning activities because they cannot

automatically be involved in the discussion (Qureshi

et al., 2023). Group members need guidance for

interaction during OCL (Le et al., 2022).

As such, we apply the ADDIE model to develop

the TransLaboration OCL environment and optimize

it to improve students’ engagement in online

discussion during collaborative translation practice.

Following Isohätälä et al. (2017); Michalsky and

Cohen (2021); Vuorenmaa et al. (2022) that SSRL

can facilitate social interaction by promoting learners’

social presence, social support, and social feedback,

we take SSR into the pedagogical consideration in

TransLaboration.

As SSR is difficult to achieve and prompts are

needed for the emergence of SSR (Kielstra et al.,

2022; Zheng et al., 2019), we embed SSR prompts in

TransLaboration to enable students to regulate their

learning activities collectively throughout the

collaboration. With the help of SSR prompts, group

members align their task perception and planning

(Järvelä & Hadwin, 2015) before the collaborative

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

368

translation task. Group members apply SSR prompts

during the translation task to ensure effective and

meaningful collaboration (Kielstra et al., 2022). Upon

completion of the translation task, SSR prompts

engage students in group evaluation and reflection,

which helps the group members improve future

learning and regulation skills (Michalsky & Cohen,

2021).

The TransLaboration OCL environment provides

students with the workspace to develop their

translation competence based on SSR. Although it is

designed with a user-friendly interface, clear structure

and scientific translation learning logic,

improvements are still needed in the following two

aspects.

At first, the integration level of TransLaboration

could be higher. The current TransLaboration

encompasses three separate components: the Moodle-

based learning portal, the QQ-based discussion tool

and KDoc-based co-authoring system. Fusing the

three components into one OCL platform would

increase the learning efficiency.

Secondly, in the current TransLaboration, the

SSR prompts function in a manual method. Students

need to refer to the SSR prompts by themselves or by

the group member who acts as the prompter. The AI-

enhanced self-adaptive SSR prompts could be

developed into TransLaboration to prompt students

to use the appropriate SSR strategies so as to make

them better involved in collaborative translation

learning.

For further study, we plan to validate the

effectiveness TransLaboration in improving students’

translation practice competence. SSR prompts

stimulate students’ cognitive cognitive performance

(Järvelä et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2019) including

critical thinking and creative thinking skills, which

significantly impact students’ translation

performance (Cheng, 2022; Li et al., 2022). As a

future study, we plan to conduct research to assess the

effect of TransLaboration on students’ translation

performance and higher-order thinking skills. Besides,

students’ log files and discussion scripts can be

gathered from TransLaboration to analyse students’

social interaction during OCL.

REFERENCES

Al-Shehari, K. (2017). Collaborative learning: trainee

translators tasked to translate Wikipedia entries from

English into Arabic. The Interpreter and Translator

Trainer, 11(4), 357-372.

Amini, M., Ravindran, L., & Lee, K.-F. (2022). A review

of the challenges and merits of collaborative learning in

online translation classes. Journal of Research, Policy

& Practice of Teachers and Teacher Education, 12(1),

69-79.

Barros, E. H. (2011). Collaborative learning in the

translation classroom: preliminary survey results. The

Journal of Specialised Translation, 16(3), 42-60.

Bayraktar Özer, Ö., & Hastürkoğlu, G. (2020). Designing

Collaborative Learning Environment in Translator

Training: An Empirical Research. Research in

Language, 18, 137-150.

Borge, M., Aldemir, T., & Xia, Y. (2022). How teams learn

to regulate collaborative processes with technological

support. Educational Technology Research and

Development, 70(3), 661-690.

Chen, X., Luo, C., & Zhang, J. (2019). Shared Regulation:

A New Research and Practice Framework for

Collaborative Learning. Journal of distance

education(1), 7.

Cheng, S. (2022). Exploring the role of translators’ emotion

regulation and critical thinking ability in translation

performance. Frontiers in psychology, 13.

Drljača, D., Latinović, B., Stankovic, Z., & Cvetkovic, D.

(2017). ADDIE Model for Development of E-Courses.

Sinteza 2017 - International Scientific Conference on

Information Technology and Data Related Research.

Gamage, S. H. P. W., Ayres, J. R., & Behrend, M. B.

(2022). A systematic review on trends in using Moodle

for teaching and learning. International Journal of

STEM Education, 9(1), 9.

Grau, V., & Whitebread, D. (2012). Self and social

regulation of learning during collaborative activities in

the classroom: The interplay of individual and group

cognition. Learning and Instruction, 22(6), 401-412.

Hadwin, A., Järvelä, S., & Miller, M. (2011). Self-

regulated, co-regulated, and socially share regulation of

learning. Handbook of self-regulation of learning and

performance, 2011, 65-84.

Hurme, T.-R., Merenluoto, K., & Järvelä, S. (2009).

Socially shared metacognition of pre-service primary

teachers in a computer-supported mathematics course

and their feelings of task difficulty: A case study.

Educational Research and Evaluation, 15(5), 503-524.

Isohätälä, J., Järvenoja, H., & Järvelä, S. (2017). Socially

shared regulation of learning and participation in social

interaction in collaborative learning. International

Journal of Educational Research, 81, 11-24.

Järvelä, S., & Hadwin, A. (2015). Promoting and

researching adaptive regulation: New Frontiers for

CSCL research. Computers in Human Behavior, 52,

559-561.

Järvelä, S., Järvenoja, H., Malmberg, J., & Hadwin, A.

(2013). Exploring socially-shared regulation in the

context of collaboration. The Journal of Cognitive

Education and Psychology, 12, 267-286.

Järvelä, S., Kirschner, P. A., Hadwin, A., Järvenoja, H.,

Malmberg, J., Miller, M., & Laru, J. (2016). Socially

shared regulation of learning in CSCL: understanding

and prompting individual- and group-level shared

TransLaboration: An Online Collaborative Learning Environment with Socially Shared Regulation Prompts in Translation Classroom

369

regulatory activities. International Journal of

Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 11(3),

263-280.

Järvelä, S., Kirschner, P. A., Panadero, E., Malmberg, J.,

Phielix, C., Jaspers, J., Koivuniemi, M., & Järvenoja,

H. (2014). Enhancing socially shared regulation in

collaborative learning groups: designing for CSCL

regulation tools. Educational Technology Research and

Development, 63(1), 125-142.

Johler, M. (2022). Collaboration and communication in

blended learning environments. Frontiers in Education,

7.

Johnson-Barlow, E. M., & Lehnen, C. (2021). A scoping

review of the application of systematic instructional

design and instructional design models by academic

librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship,

47(5).

Kielstra, J., Molenaar, I., van Steensel, R., & Verhoeven, L.

(2022). Supporting socially shared regulation during

collaborative task-oriented reading. International

Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative

Learning, 17(1), 65-105.

Le, V. T., Nguyen, N. H., Tran, T. L. N., Nguyen, L. T.,

Nguyen, T. A., & Nguyen, M. T. (2022). The

interaction patterns of pandemic-initiated online

teaching: How teachers adapted. System, 105, 102755.

Li, J., Liu, J., Yuan, R., & Shadiev, R. (2022). The Influence

of Socially Shared Regulation on Computational

Thinking Performance in Cooperative Learning.

Educational Technology and Society, 25(1), 48-60.

Li, Y. (2018). Fusion of Critical Thinking and Translation

Teaching. Journal of Guangzhou Polytechnic Normal

University, 6.

Michalsky, T., & Cohen, A. (2021). Prompting Socially

Shared Regulation of Learning and Creativity in

Solving STEM Problems. Frontiers in psychology, 12.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722535

Moghaddas, M., & Khoshsaligheh, M. (2019).

Implementing project-based learning in a Persian

translation class: a mixed-methods study. The

Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 13(2), 190-209.

Muruganantham, G. (2015). Developing of E-content

package by using ADDIE model. International journal

of applied research, 1, 52-54.

Ng, P. M. L., Chan, J. K. Y., & Lit, K. K. (2022). Student

learning performance in online collaborative learning.

Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 8129-

8145.

Oyarzun, B., & Martin, F. (2023). A Systematic Review of

Research on Online Learner Collaboration from 2012–

21: Collaboration Technologies, Design, Facilitation,

and Outcomes. Online Learning, 27.

Panadero, E., & Järvelä, S. (2015). Socially Shared

Regulation of Learning: A Review. European

Psychologist, 20, 190-203.

Panadero, E., Kirschner, P., Järvelä, S., Malmberg, J., &

Järvenoja, H. (2015). How Individual Self-Regulation

Affects Group Regulation and Performance: A Shared

Regulation Intervention. Small Group Research, 46,

431-454.

Picciano, A. G. (2021). Theories and frameworks for online

education. Guide Adm Distance Learn, 2, 79-103.

Pitkäsalo, E., & Ketola, A. (2018). Collaborative translation

in a virtual classroom: Proposal for a course design.

Transletters. International Journal of Translation and

Interpreting(1), 93-119.

Qureshi, M. A., Khaskheli, A., Qureshi, J. A., Raza, S. A.,

& Yousufi, S. Q. (2023). Factors affecting students’

learning performance through collaborative learning

and engagement. Interactive Learning Environments,

31(4), 2371-2391.

Robinson, H., Kilgore, W., & Warren, S. (2017). Care,

communication, support: Core for designing

meaningful online collaborative learning. Online

Learning Journal, 21(4).

Smith, E. E. (2017). Social media in undergraduate

learning: categories and characteristics. International

Journal of Educational Technology in Higher

Education, 14(1), 12.

Spatioti, A. G., Kazanidis, I., & Pange, J. (2022). A

Comparative Study of the ADDIE Instructional Design

Model in Distance Education. Information, 13(9), 402.

Tekwa, K. (2023). Process-oriented collaborative

translation within the training environment: comparing

team and individual trainee performances using a

video-ethnography approach. Education and

Information Technologies.

Turiman, S., C Suppiah, P., Nozakiah Tazijan, F., Ravinthra

Nath, P., & Shamshul Bahrn, F. F. (2023). Online

Collaborative Translation in Translation Classrooms:

Students’ Perceptions and Attitudes. AWEJ for

Translation & Literary Studies, 7(3).

Vuorenmaa, E., Järvelä, S., Dindar, M., & Järvenoja, H.

(2022). Sequential Patterns in Social Interaction States

for Regulation in Collaborative Learning. Small Group

Research.

Vygotsky. (1978). Mind in Society: Development of Higher

Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

Zheng, L., Li, X., Zhang, X., & Sun, W. (2019). The effects

of group metacognitive scaffolding on group

metacognitive behaviors, group performance, and

cognitive load in computer-supported collaborative

learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 42, 13-

24.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

370