Aesthetics as a Decisive and Motivational Factor for Online Training

Anaïs Niveau and Jean-Christophe Sakdavong

CLLE CNRS UMR 5263, University of Toulouse, 5 allée Antonio Machado, Toulouse, France

Keywords: E-Learning, Digital Learning, Aesthetics, Credibility, Purchase Intention, Learning Motivation.

Abstract: In an increasingly competitive world, including that of online education and training, it is important to stand

out from the crowd if one wants to attract learners, and therefore customers. Studies show the importance of

a website’s credibility in influencing the intention to buy a service, while others show the impact of a teacher’s

credibility on motivation to learn. Researchers have also shown that an important factor in an individual’s

assessment of credibility is based on visual appearance, or “aesthetics”. This is why we wanted to check that,

for the same training content, an individual would be more inclined to opt for a site that he or she considered

aesthetically pleasing than for another that he or she did not consider aesthetically pleasing. We therefore had

2 training websites evaluated, one “aesthetic” and the other “non-aesthetic”, divided randomly between 2

groups of participants (82 in total). The results of our survey show a preference for the “aesthetic” site when

it comes to evaluating the credibility of the site, the credibility of the training, the intention to buy and the

motivation to learn. We then suggest some avenues for future research.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital technology is omnipresent in education,

leading to an abundance of scientific studies and the

principles that stem from them. For example, Mayer’s

multimedia learning principles (2001) guide

instructional designers in creating pedagogically

effective digital resources. In order to guarantee

inclusivity, accessibility and usability are also

prioritised, taking into account elements like colour

contrast, layout guidelines, and readable font choices.

But design and aesthetics are frequently

overlooked in favour of pedagogy, usability, and

accessibility, raising the question of why this

happens.

The design principle of “form follows function”

suggests that aesthetics should follow functionality in

design. This principle has both descriptive and

prescriptive interpretations, with the latter implying

that aesthetics are secondary to functionality (Lidwell

et al., 2010). This viewpoint aligns with the historical

mind-body dichotomy, where the mind (function) is

deemed superior to the body (form) (Gray et al.,

2011).

Aesthetics and pedagogical content are

inextricably linked for people who create educational

resources and digital learning materials in the field of

instructional design and graphic design. Numerous

research works, including those by Mayer (2001),

Lohr (2007), and Clark and Lyons (2004), highlight

the cognitive advantages of aesthetics in supporting

learning. To improve the learning process, Lohr

(2007) suggests taking visual aesthetics into account

while designing instructional materials.

Examining additional factors is crucial, especially

in light of aesthetics’ demonstrated cognitive

benefits.

In this study, we wanted to check if aesthetic has

an effect on credibility, intention to buy and

motivation to learn in a learning website. Our main

findings will show that it has a significant effect on

all these variables.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Observation

The saying “Don’t judge a book by its cover” captures

the idea that beauty and aesthetics are often perceived

as superficial elements that do not necessarily reflect

the content or substance. Yet, it is undeniable that

colourful and engaging book covers attract the

attention of potential readers. The cover is the initial

entry point into a book, sparking interest, prompting

readers to pick it up, read the synopsis, and make the

78

Niveau, A. and Sakdavong, J.

Aesthetics as a Decisive and Motivational Factor for Online Training.

DOI: 10.5220/0012618700003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 78-90

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

decision to purchase it. This principle also applies to

marketing, visual communication, and product

design, amongst others.

In this context, it is relevant to extend this

observation to education and training. In today’s

world, especially in the post-COVID era, the

availability of online learning options is increasing

exponentially (KPMG, 2015; Research and Markets,

2023). The global e-learning market has been

growing rapidly, and competition amongst

educational providers is intensifying.

2.2 Research Questions

In this competitive context, what influences

prospective learners’ choices between seemingly

equivalent educational offerings? Does the aesthetics

and visual appeal of a learning platform impact the

learner’s perception of its credibility and,

consequently, their intention to enrol (and pay) for a

course?

Beyond being a deciding factor, does aesthetics

and visual appeal affect the motivation of enrolled

learners in a course?

Exploring these questions is the goal of this

investigation. To accomplish this, we will start by

defining important terms like credibility, learning

motivation, and aesthetics through a study of

theoretical and empirical literature. We will next

synthesize these studies to determine the connections

between these concepts and propose one or more

research hypotheses. Lastly, we will describe an

experimental protocol used to test these hypotheses.

2.3 Credibility

Credibility is a fundamental concept in assessing the

trustworthiness and expertise (Choi, 2020; Choi &

Stvilia, 2015; Rieh, 2010) of information sources,

influencing people’s confidence in the information’s

accuracy. This review explores the dimensions of

credibility and its evolving nature, with a specific

focus on digital credibility in online learning

environments.

According to Rieh (2010), credibility has been

traditionally characterized by three primary

dimensions:

• Source Credibility which refers to the perceived

reliability of the individual communicating the

information.

• Message Credibility which concerns the

apparent reliability of the content, structure,

language, and presentation used to convey the

information.

• Media Credibility which deals with the

perceived reliability of the channel used for

information dissemination, such as television,

radio, or newspapers.

The evolution of technology has given rise to

contemporary considerations of credibility,

particularly in the digital realm. Two significant

aspects of digital credibility have emerged:

• Web Credibility which relates to the ambiguity

of the source and the relative youth of the

medium.

• Computer Credibility which relates to the

computer as a source of information

(“knowledge repositories, user instructions,

etc.”). It comprises four subtypes:

o Presumed Credibility: Based on individual

beliefs and assumptions.

o Reputed Credibility: Rooted in what is

reported by third parties, such as other

individuals, the media, or institutions.

o Surface Credibility: Hinging on initial

impressions and superficial traits, such as

website design, visual elements, and

information architecture.

o Experienced Credibility: Based on

individual experiences with the source.

Various frameworks have been proposed to assess

digital credibility. Amongst these, Fogg’s Web

Credibility Framework identifies three key factors

(cited in Choi & Stvilia, 2015):

a. The operator of the site

b. The content provided

c. The design of the website, including

information structure, technical design,

aesthetic design, and interaction design.

Online learning environments found on websites

being the focus of this study, it is critical to define the

exact criteria that will be used to determine the

credibility of these settings. Credibility of online

learning platforms is mostly based on elements such

as the overall user experience, the calibre of the

course content, the platform’s navigability, and the

standing of the course provider.

Credibility is a multifaceted concept that has

expanded from traditional dimensions to include

several types of digital credibility. Factors impacting

credibility in online learning environments are: the

information’s original source, the calibre of the

content, and the platform’s functionality and design

(Metzger et al., 2013). It is crucial to comprehend and

assess credibility in digital environments to make sure

that online learners can rely on and trust the

information they encounter.

Aesthetics as a Decisive and Motivational Factor for Online Training

79

2.3.1 Website Credibility

Choi (2020) and Choi and Stvilia (2015) propose to

combine the concepts of trustworthiness and

expertise with Fogg’s framework (operator, content

and design) for a comprehensive assessment of a

website’s credibility through 6 criteria:

1. Operator Trustworthiness

2. Operator Expertise

3. Content Trustworthiness

4. Content Expertise

5. Design Trustworthiness

6. Design Expertise

Given the vast amount of information available on

the internet and the increasing awareness of fake

news and disinformation, the importance of source

credibility has become clear. This impact is

particularly prominent since the 2016 U.S.

presidential elections (Azzimonti & Fernandes, 2023;

Choi & Stvilia, 2015).

2.3.2 Credibility in Education: Cognitive

Authority

Within the realm of education, cognitive authority is

essential. This term describes people who are

regarded as authorities in particular domains,

including psychology, education, philosophy, and

more (Rieh, 2010; Wilson, 1983). Three essential

factors for credibility have been determined by

studies conducted by McCroskey et al. (quoted in

Finn et al., 2009): perceived benevolence,

competence, and reliability. Since the instructor

serves as the main information source in teacher-

centred learning approaches, credibility is especially

important. Students who think well of their teachers

are more inclined to enrol in more courses taught by

them and to refer others to them.

Trust being a significant factor in e-commerce,

users’ lack of trust is a common barrier to and an

important factor for online purchases (Chong et al.,

2003; Saw & Inthiran, 2022). Since online learning

often involves financial transactions on websites,

e-commerce credibility criteria can be applicable.

Ensuring that an online education platform is

perceived as credible and reliable is essential for

attracting and retaining learners.

2.3.3 Aesthetics and Website Credibility:

“What Is Good Is Beautiful”

Studies, such as the one by Dion et al. (1972), have

shown that visually appealing people can enhance

perceptions of credibility. The concept of “what is

beautiful is good” may extend beyond physical

attractiveness to include the visual aspects of

websites.

2.3.4 Prominence Interpretation Theory

(PIT): Understanding Website

Credibility Evaluation

The Prominence Interpretation Theory (PIT) (Fogg,

2003), sheds light on how people assess the

credibility of websites. For the purpose of

determining credibility, prominence and

interpretation must both be present. On a website,

prominence refers to an element’s visibility, whereas

interpretation is the result of user judgement. Both

prominence and interpretation are influenced by

multiple factors, such as individual differences, user

involvement, website theme, user task, and user

experience.

In digital contexts, credibility is a complex idea

with very large effects. It is crucial for e-commerce,

education, and other online activities. Then, it is

essential to comprehend the several aspects of

credibility, such as the role of aesthetics and cognitive

authority, to create and maintain trustworthy online

platforms.

2.4 Aesthetics

The Cambridge Dictionary defines something as

“aesthetically pleasing” as “something that is

enjoyable to look at because you think it is beautiful”.

While this might be commonly understood, it is

important to define how this pertains to websites and

online education.

2.4.1 “What Is Beautiful Is Usable”

The notion that “what is beautiful is good,”

introduced by Dion et al. in 1972 is extended to the

realm of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) by

Tractinsky and colleagues in 2000. Their research

demonstrates that users associate aesthetics with

usability, emphasizing the significance of aesthetics

in the design process. Moreover, Hancock (2004)

defines the aesthetics of a digital learning

environment as “an emotional response evoked by

visual elements within a learning environment”.

Consequently, several key considerations are outlined

for achieving a successful interface. When addressing

the aesthetics of a digital object, the focus is not just

on displaying images or graphics on the screen but

rather on intentionally arranging elements to engage

the user’s senses and emotions, a practice commonly

associated with the principles of Gestalt theory.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

80

2.4.2 Gestalt Theory

The Gestalt Theory, also known as Gestaltism,

originated in Germany and Austria in the early 20

th

century through the works of Max Wertheimer, Kurt

Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler (Köhler, 1967). This

theory was built on the premise that “the whole is

greater than the sum of its parts” (Rock & Palmer,

1990), a fundamental principle that governs sensory

perceptions. According to Todorovic (2008), several

laws and principles derived from Gestalt Theory are

regularly used in fields such as graphic design,

interior design, and user interface design (UI). These

principles include:

• Figure-Ground Articulation: The contrast

between a figure and its background, where the

figure is perceived as salient and deserving of

attention.

• Proximity Principle: Elements placed close to

each other are perceived as a group.

• Common Fate Principle: Elements moving in

the same direction are seen as a group.

• Similarity Principle: Elements with similar

attributes (e.g., shape, colour, size) are

perceived as belonging to the same group.

• Continuity or Continuation Principle: Aligned

or connected elements are perceived as a group.

• Closure Principle: Elements forming a closed

figure are grouped together.

• Good Gestalt Principle: Individuals interpret

complex shapes in the simplest possible way.

It is worth mentioning that, still according to

Todorovic (2008), there is no definitive list of Gestalt

principles but that the aforementioned laws are the

most known.

The Gestalt Theory’s wide application in the

design of user interfaces and user experiences

underlines its relevance in creating effective and

functional digital experiences.

2.4.3 Facets of Visual Aesthetics for

Websites

Moshagen and Thielsch (2010) introduce four

objective facets of visual aesthetics for websites,

partly based on Gestalt principles, referred to as the

Visual Aesthetics of Website Inventory (VisAWI):

• Simplicity: Emphasizing unity, homogeneity,

order, and clarity, simple presentations tend to

be processed more smoothly and are positively

appreciated.

• Diversity: Stimulating interest and tension,

diversity counters low levels of arousal induced

by overly simple stimuli.

• Colourfulness: The use of colours significantly

impacts a website’s aesthetic evaluation.

• Craftsmanship: Skilful and coherent integration

of relevant design dimensions.

These criteria become central to the assessment of

website aesthetics, which is further elaborated in this

study’s methodology section.

2.4.4 Use of Colours, Psychology, and

Marketing

The choice of colour palettes holds significance in

shaping a user’s perception of a website. Several

studies have demonstrated the role of colour in

influencing the perceived attributes of an object

(Papachristos et al., 2005; Singh & Srivastava, 2011;

Suriadi et al., 2022). Colours, or combinations of

colours, also have a notable impact on brand

perception and consumer behaviour. Singh and

Srivastava (2011) present a selection of colour

meanings used to convey specific messages in

marketing. The study underscores the importance of

these colour choices, especially when it comes to web

design.

The second part of this scientific summary

focuses on the impact of aesthetics in education and

online learning, considering the role of aesthetics in

designing digital learning environments. Hancock

(2004) evaluates the impact of aesthetics on student

engagement and motivation in digital learning spaces.

His research demonstrates a preference for

aesthetically pleasant surroundings, emphasising the

importance of creating visually appealing e-learning

platforms. A study by Ghai and Tandon (2022)

evaluates the visual design components that influence

the e-learning experience. Their research identifies

many aspects, such as graphics, typography, and

layout, that greatly contribute to enhancing learners’

engagement and motivation.

Furthermore, this scientific summary discusses

the rapid judgments formed by users about the

aesthetics of websites, noting that over 45% of users

evaluate a website’s credibility based on its

appearance (Fogg et al., 2003). A study by Lindgaard

and colleagues (2006) suggests that users form

opinions about website aesthetics in as little as

50 milliseconds, highlighting the need for a visually

appealing website to capture and retain users’

attention.

The role of aesthetics in data visualization,

especially in educational infographics, is also

explored. This section emphasizes the importance of

colour choices and complexity in infographics, as

they affect user engagement and the retention of

Aesthetics as a Decisive and Motivational Factor for Online Training

81

information in educational materials (Harrison et al.,

2015).

We have seen a comprehensive overview of the

role of aesthetics in design, particularly in the contexts

of web design and online learning. It highlights the

essential aspects of aesthetics, incorporating principles

from the Gestalt Theory and the facets of visual

aesthetics. This study underlines the significance of

aesthetics in user experience, engagement, and

credibility in digital environments, emphasising the

need for designers and educators to consider aesthetics

as a fundamental element in their work.

2.5 Overview

As we have seen, when it comes to credibility, many

criteria can influence its perception by a user

browsing a website (Choi, 2020; Choi & Stvilia,

2015; Fogg, 2003; Fogg et al., 2003; Rieh, 2010).

However, web credibility is crucial at a time when

fake news and all types of disinformation are rife

(Azzimonti & Fernandes, 2023; Choi & Stvilia,

2015). In addition, credibility has an important impact

for learners at cognitive and metacognitive levels

when it comes to cognitive authority, and therefore

the teacher (Finn et al., 2009). The same goes for the

trust placed by users in e-commerce sites if the user

wishes to have confidence before proceeding, for

example, with an online purchase (Chong et al., 2003;

Saw & Inthiran, 2022).

The factors listed as bearers of credibility very

often relate to aesthetics, amongst other elements

(Choi & Stvilia, 2015; Fogg et al., 2003; Rieh, 2010).

This could be due to the popular perception that “what

is beautiful is good” (Dion et al., 1972; Tractinsky et

al., 2000) and the importance of making a good

impression in the first moments of exposure to the

digital element (Lindgaard et al., 2006).

Several empirical studies have noted the impact of

the visual aspect of digital resources belonging to the

learning framework such as digital training

environments (Ghai & Tandon, 2022; Hancock,

2004) and infographics (Harrison et al., 2015) on

motivation, engagement and general perception of the

resource.

On the other hand, there is, to our knowledge, no

study focusing specifically on the importance of

aesthetics on the perceived credibility of an online

training website and on the training itself, nor on the

intention of registration (and therefore purchase), or

even on the motivation felt by the (future) learner.

To develop a solid methodology, we will

formulate our research hypotheses taking into

account the “objective” aesthetic and the “perceived”

aesthetic. The former will be the aesthetic by design

(it respects the aesthetic rules) and the latter will be

subjectively measured by the users.

In the rest of this article, we will call the

“aesthetic” website, the one that respects the aesthetic

rules, and the “non aesthetic” one, the one that doesn’t

respect them.

2.6 Research Hypotheses

H1: an aesthetic website is perceived as being more

aesthetic than a non-aesthetic one

H2a: an aesthetic website is perceived as being more

credible than a non-aesthetic one

H2b: a website perceived as more aesthetic is

perceived as being more credible than if it is

perceived less aesthetics

H3a: an online training offered on an aesthetic

website is perceived as being more credible than on

a non-aesthetic one.

H3b: an online training hosted on a website perceived

as more aesthetic is perceived as being more

credible than if it is hosted by a website perceived as

less aesthetics

H4a: an individual will be more inclined to pay for

an online training offered on an aesthetic website than

on a non-aesthetic one

H4b: an individual will be more inclined to pay for

an online training hosted on a website perceived as

more aesthetic than on a less aesthetics

H5a: an individual will be more motivated in his or

her learning with an online training offered on an

aesthetic website than on a non-aesthetic one

H5b: an individual will be more motivated in his or

her learning with an online training hosted on a

website perceived as more aesthetic than if it is hosted

by a website perceived as less aesthetics.

3 METHODOLOGY

To test these hypotheses, 2 websites, one aesthetic

and the other non-aesthetic were evaluated by

participants. Perception of the aesthetic of the website

was measured to verify H1, and perceptions of the

credibility of the website, the credibility of the online

training course, the intention to purchase and

motivation to learn were measured to verify all other

hypotheses.

3.1 Participants

To allow collection of sufficient data, a bilingual

(French and English) online survey was created

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

82

through LimeSurvey and distributed via public

posting on the professional media platform LinkedIn

as well as direct messaging. This survey was open

from beginning of July 2023 to mid-August 2023. In

compliance with the RGPD, the anonymous data was

stored securely on a server at the University of

Toulouse.

No selection was implemented other than being

over the age of 18 and not to suffer from uncorrected

visual impairment, the accurate evaluation of

aesthetics being based on visual perception.

82 participants completed the survey (55 women, 27

men, 0 non-binaries).

3.2 Materials and Apparatus

Participants were asked to evaluate 2 websites: one

objectively considered aesthetic (Figure 1) that

respects general rules such as Gestalt principles and

colour uses, and one objectively non-aesthetic (Figure

2) that doesn’t respect these general rules. Both were

inspired by existing e-learning websites, from which3

screenshots were extracted for each. To reduce

Figure 1: 3 Screen captures of the aesthetic website.

Figure 2: 3 Screen captures of the non-aesthetic website.

potential biases, each site was evaluated by a separate

group, was sufficiently modified to reduce the risk of

potential biases such as prior knowledge of the site

(Dam, 2020), and the opinions of Internet users were

obliterated to remove the factor of “reputed

credibility” (Rieh, 2010), parasitic in the case in

question, and to focus attention on aesthetics alone.

To verify the hypotheses, participants must then

evaluate the 18 points of the VisAWI (Moshagen and

Thielsch, 2010) measured by a Likert scale between

0 and 6 for a total score theoretically between 0 and

108.

4 additional points assessing credibility of a

website, credibility of an online training course,

potential intention to buy, and motivation to learn

were all measured by a Likert scale between 0 and 5

(no neutral choice to ensure a clear statement by the

participant) for a total score theoretically between 0

and 5 for each item:

• “I think this website is trustworthy.”

• “I think the training offered by this website is

trustworthy.”

Aesthetics as a Decisive and Motivational Factor for Online Training

83

• “I would be prepared to pay to register for

training on this website.”

•

“I find the aesthetics of this website motivating

for my learning.”

3.3 Procedure

After basic consent and identifying information (age,

gender, socio-professional category, level of

education, experience of online training, experience

of the importance of aesthetics in general),

participants were invited to observe, during 1 minute,

3 screenshots from one out of two sites (randomly

presented by LimeSurvey). Each website, one

aesthetic and the second non-aesthetic, was evaluated

by separate groups to eliminate a bias that could arise

from exposure to an aesthetic website before

evaluating a non-aesthetic one, and vice versa. After

the time of observation, participants must evaluate the

18 statements of the VisAWI, then the 4 elements

concerning the credibility of the website, the

credibility of the online training, the intension to

purchase, and the motivation to learn. The survey

then finished by thanking the participants for their

participation.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Sample

102 people started the survey and 82 completed it.

From this sample, a profile can be drawn up with the

following characteristics.

A majority of women responded to the survey, 55

versus 27 men. The average age of the participants is

43.7 years (44.6 years for women, 41.7 years for

men).

The most represented socio-professional category

is employees (37.8%) followed by executive or

higher intellectual professions (30.5%).

In the sample, half of the participants have never

experienced paid online training, although the

proportion is higher for women (34.1%, compared to

15.9% for men). Only 20.8% of the participant have

never experienced free online training (15.9% of

women, compared to 4.9% of men)

70.7% of the participants answered in French and

29.3% in English.

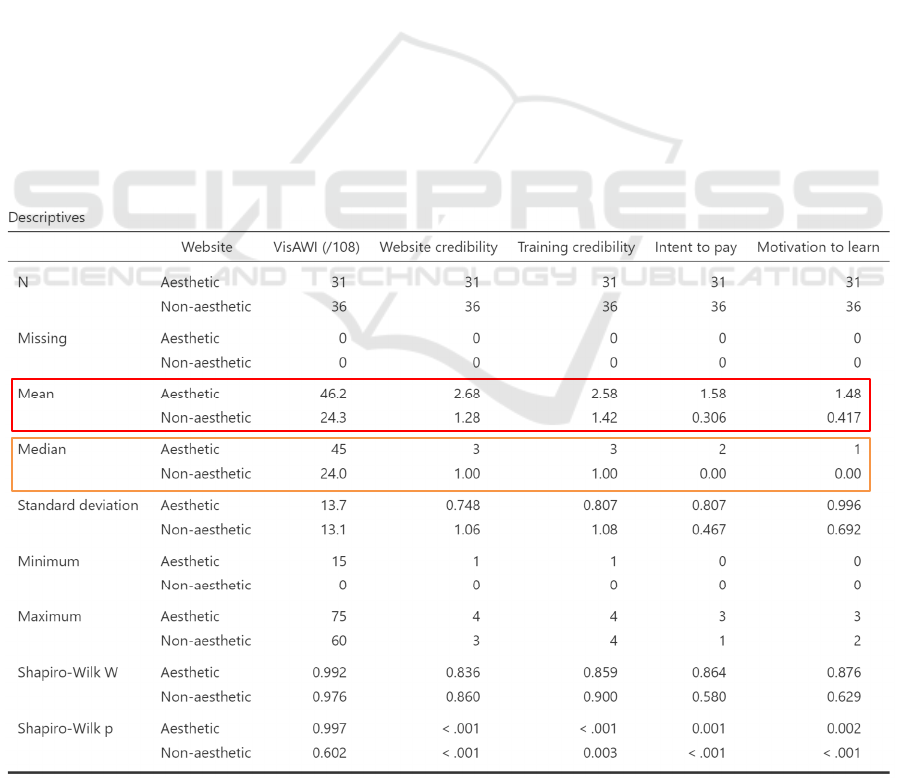

Table 1: Descriptive data split by website (aesthetic and non-aesthetic).

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

84

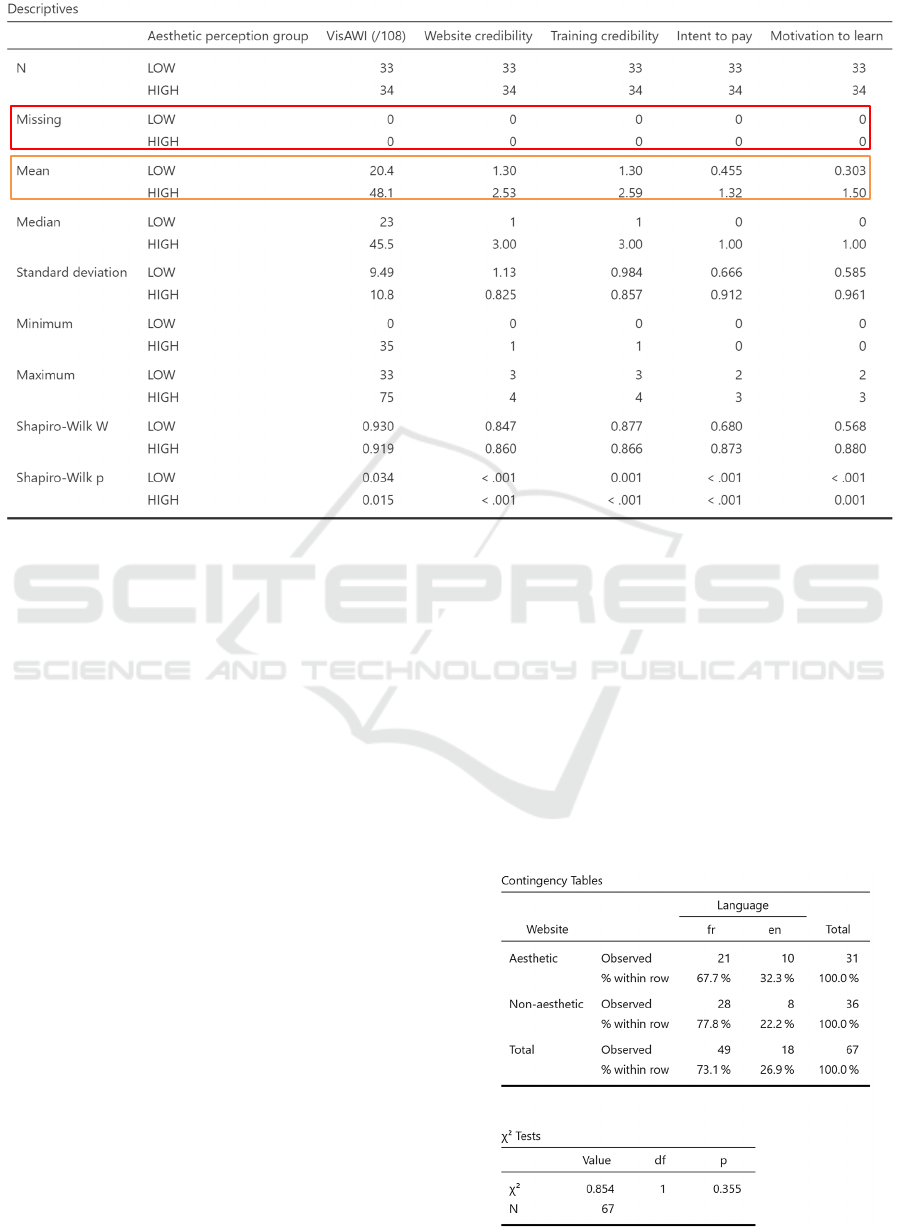

Table 2: Descriptive data split by aesthetic perception score (VisAWI).

4.2 Descriptive Processing of Data

To verify H1, H2a, H3a, H4a and H5a, participants

are split in two groups, the first one (41) viewing the

“non-aesthetic” website and the second one (38)

viewing the “aesthetic” website.

To verify H2b, H3b, H4b and H5b, participants

are also split in two groups using their answer to the

VisAWI questionnaire to separate them. The first

group (“LOW”) is composed of the participants

having a score lower than the global average score,

and the second group (“HIGH”) with a higher score.

As participants were not in a controlled

environment, precautions were taken, and 15 outliers

were identified using Jamovi software and excluded

from the study. 49 women and 18 men remained.

After removing the outliers, there are 36

participants in the aesthetic website group, 31 in the

non-aesthetic one. Since the VisAWI average score is

34.5, there are 33 participants in the LOW aesthetic

perception group and 34 in the HIGH one.

Table 1 shows that the means of the variables

VisAWI score, credibility of the website, credibility

of online training, intention to pay and motivation of

the “aesthetic group” are much higher than for the

other group. It is also true for the medians. These

descriptive data are coherent with our hypotheses H1,

H2a, H3a, H4a and H5a.

Table 2 shows that the means of the variables

credibility of the website, credibility of the online

training, intention to pay and motivation of the HIGH

perceived aesthetic group are much higher than for

the other group. It is also true for the medians. These

descriptive data are coherent with our hypotheses

H2b, H3b, H4b and H5b.

A Chi-test shows that the language of the

participant is well distributed between the two groups

(Table 3).

Table 3: Contingency tables between website and survey

language.

Aesthetics as a Decisive and Motivational Factor for Online Training

85

4.3 Inferential Statistics

To evaluate our hypothesis H1, we carry out a T-test

between the website (two independent groups) and

the VisAWI score (integer value between 0 and 108).

As shows in Table 1 with the Shapiro-Wilk test, the

two groups are normally distributed for the VisAWI.

We proceed to a Levene’s test to check the

homogeneity of variances. The result of the test

(p = .721) shows that there is homogeneity of the

variances, which allows to use a Student T-Test.

We hypothesize that the VisAWI score will be

higher in the aesthetic group.

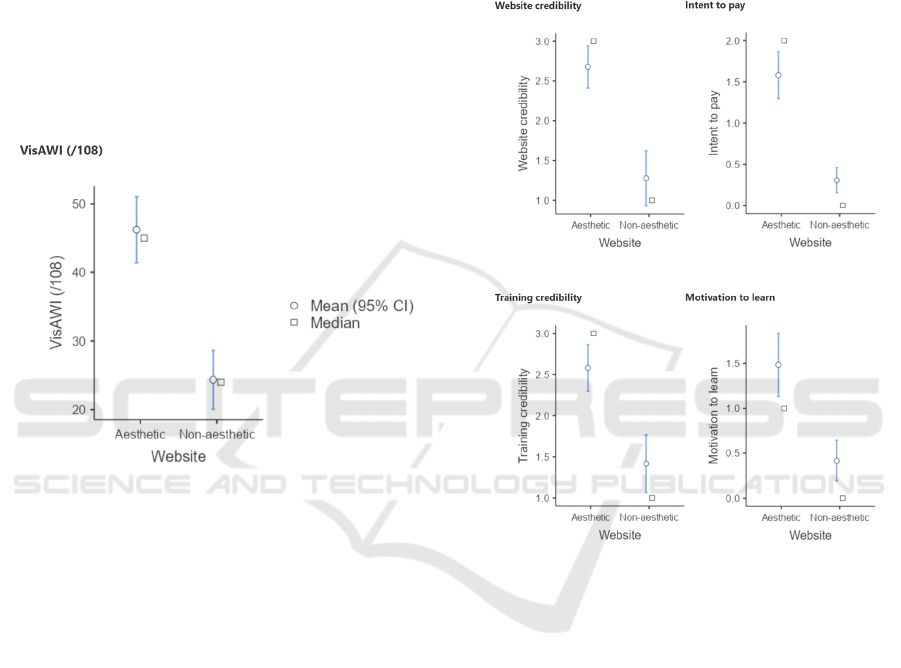

Figure 3 shows the difference between the two

groups.

Figure 3: VisAWI score split by website.

There is a significant effect of website aesthetic

over the VisAWI t(65) = 6.69, p < .001 with a large

effect size of 1.64.

We can conclude that H1 is verified.

To verify H2a, H3a, H4a and H5a, we carry out a

test between the website (two independent groups)

and the following variables: the credibility of the

website, the credibility of the online training, the

intention to pay and the motivation to learn (all coded

by integer values between 0 and 5). As Table 1 shows

with the Shapiro-Wilk test, the two groups aren’t

normally distributed for all variables. We must

proceed a Mann-Whitney U test.

We hypothesize that all these variables will be

higher in the aesthetic group which is confirmed with

p < .001 for each variable with medium effect sizes:

the credibility of the website (d = 0.681), the

credibility of the online training (d = 0.588), the

intention to pay (d = 0.788), and the motivation to

learn (d = 0.599).

We can conclude that H2a, H3a, H4a and H5a are

verified as illustrated by Figure 4.

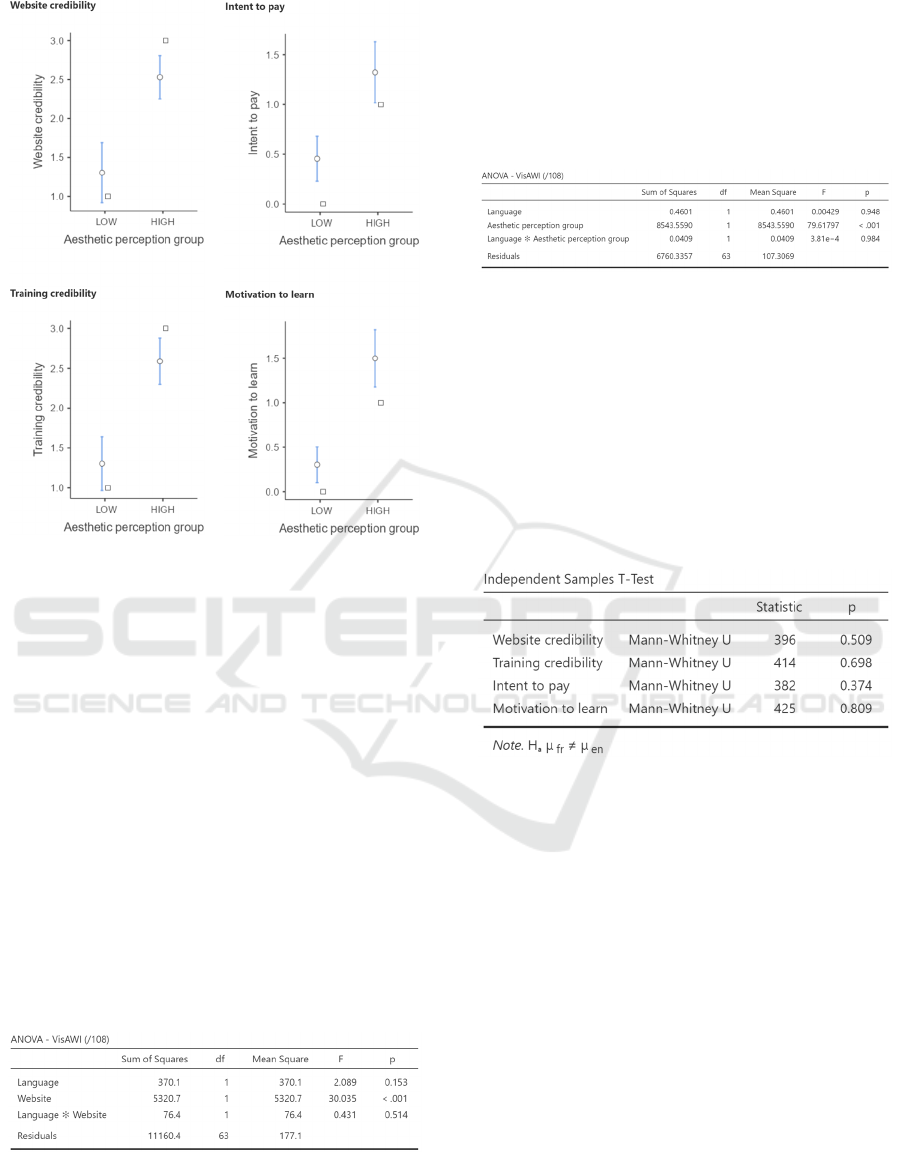

To verify H2b, H3b, H4b and H5b, we carry out a

test between the aesthetic perception variable (two

independent groups) and the following variables: the

credibility of the website, the credibility of the online

training, the intention to pay, and the motivation to

learn (all coded by integer values between 0 and 5).

As Table 2 shows with the Shapiro-Wilk test, the two

groups aren’t normally distributed for all variables.

We must proceed a Mann-Whitney U test.

Figure 4: Credibility of the website, credibility of the online

training, intention to pay, and motivation to learn split by

website aesthetic.

We hypothesize that all these variables will be

higher in the HIGH aesthetic perception group which

is confirmed with p < .001 for each variable and with

medium effect sizes: the credibility of the website

(d = 0.577), the credibility of the online training

(d = 0.643), the intention to pay (d = 0.535), and the

motivation to learn (d = 0.684).

We can conclude that H2b, H3b, H4b and H5b are

verified as illustrated by Figure 5.

As we distributed the survey in two languages, we

must verify that there is no effect of the language on

our measures of the VisAWI score, the credibility of

the website, the credibility of the online training, the

intention to pay, and the motivation to learn,

regardless of the website group or the perception

group.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

86

Figure 5: Credibility of the website, credibility of the online

training, intention to pay, and motivation to learn split by

aesthetic perception group.

This can be done by a two-factor ANOVA with

language and website group (or perception group) as

factors, and the different scores.

The verification of normal distribution for these

10 ANOVAs (5 × 2) shows that there is normality

only for VisAWI scores (split by website or by

perception).

For the website split, Shapiro-Wilk test (p = .856)

and homogeneity of the variances (Levene’s test

p = .407) are good. Table 4 shows that only the

Website (aesthetic or not) variable has an effect of the

VisAWI, which is necessary to ensure that there is no

interference of the language on the measures of

VisAWI, regardless of the group.

Table 4: Two-factor ANOVA between language, website

and VisAWI.

For the perception split, Shapiro-Wilk test

(p = .263) and homogeneity of the variances

(Levene’s test p=0.560) are good. Table 5 shows that

only the perception group has an effect of the

VisAWI, which is necessary to ensure that there is no

interference of the language on the measures on

VisAWI whatever the group is.

Table 5: Two-factor ANOVA between language, website

and VisAWI.

Table 5 shows that there is no significant effect of the

language on the VisAWI scores.

For the other variables, we cannot proceed with an

ANOVA using the group because of the non-

normality of the distribution, but we can do a non-

parametric Mann-Whitney U test using only the

language as a factor. Table 6 shows that there is no

significant effect of the language on our measures.

Table 6: Mann-Whitney U Test on the effect of language on

the credibility of the website, of the online training, the

intention to pay and the motivation to learn.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Summary of Results

Following a literature review on the importance of

aesthetic factors on dimensions such as credibility

and education, we wanted to verify several

hypotheses related to these aspects. To do this, we

proposed a survey allowing participants to evaluate

the visual appearance based on 3 screenshots of a

website. Two websites were proposed to enhance the

results and to be able to compare them to each other:

the first respects the rules of aesthetic design, while

the second does not.

Thanks to this study, we were able to verify

several hypotheses.

The first one (H1) allowed us to show that a

website designed in accordance with the rules of

Aesthetics as a Decisive and Motivational Factor for Online Training

87

aesthetic design is perceived more aesthetic than

another site that does not respect these rules.

We then wanted to verify certain variables that, in

our opinion, follow from “successful” aesthetics.

Indeed, an “aesthetic” website (H2a) and online

training (H3a) are considered to be more credible than

when these rules have not been respected. Similarly,

an individual will be more likely to pay for training

(H4a) based on an aesthetic website than if the site

that hosts it is not. Finally, an individual will feel

more motivated in their learning (H5a) if the training

is designed by respecting these rules of aesthetics.

Moreover, we were able to show the same results

(H2b, H3b, H4b, H5b), provided that the individual

perceives the site or training as being aesthetic for

them, even beyond all considerations of aesthetic

rules. This could be explained by the fact that, while

aesthetics must respect rules, it remains a matter of

taste, and a person can naturally find something more

aesthetic than another person, whether for cultural or

other reasons.

These very positive first results give us leads for

additional research that could be conducted.

5.2 Research Perspectives

Here we have proposed 2 existing sites positioned at

the extremes of an aesthetic prism: one professional

respecting the rules of aesthetics, and the other

amateur not respecting them. However, it could be

interesting to evaluate the impact of the aesthetics of

sites with “intermediate” aesthetics as well. Or, just

as Hancock (2004) did by comparing 2 versions of the

same LMS (Learning Management System), propose

an “aesthetic” version and a “neutral” version of a

training; or by varying only one parameter to try to

define more precisely which aesthetic rule

predominates, or which rule can be a real deal

breaker, THE rule that cannot be broken at the risk of

losing all credibility.

It would also be possible to repeat the same study

but, this time, not to exclude people with a visual

impairment, and instead target one or other specific

visual impairment (such as colour-blindness) to

measure its impact on the results.

We could also consider extending the questioning

beyond the simple website hosting the training to

include presentation slides by a teacher or trainer,

infographics (like Ghai & Tandon, 2022), educational

videos, and any other educational support or resource.

Finally, the sample being composed of voluntary

individuals for the needs of this experiment, one can

wonder what the results would be if one asked the

question of purchase intention to real visitors of a

website offering online training, and the question of

motivation in learning to real learners enrolled in a

training. Since our sample did not necessarily have a

real interest in the training offered on the sites used in

this experiment, even if we instructed them to base

their judgment only on the visual aspect, perhaps the

result would be even more convincing on real users.

Indeed, while aesthetics has been repeatedly

highlighted as being a primordial factor of credibility,

it is naturally not the only and unique evaluation

factor, as we have been able to develop in the state of

the art. Other variables could therefore be included to

verify their relevance.

6 CONCLUSION

Our aim here is to highlight the importance of

aesthetics in the world of education. Often, form is

disregarded in favour of content: the focus is on the

content, to the detriment of the visual aspect of the

resource or medium, which is considered to be

secondary or even a nuisance. Yet in an increasingly

competitive world, and with the exponential growth

of online training, it is important for any company,

large or small, to be able to stand out from the crowd.

While content is of course essential, it is also vital to

make a good impression on potential future

customers, and in increasingly record times. Faced

with multiple offers for the same training course, we

need to find that little bit extra that will make

someone decide to sign up for our training course, or,

in other words, to pay for the service we offer.

One of the most direct ways of making a good

impression is based on the visual aspect, since this is

the first approach that people (without visual

impairment) will have. We have therefore been able

to demonstrate this impact from a number of angles

in order to highlight the importance of thinking

aesthetically about the educational services on offer,

and in so doing try to eradicate the idea that content

is all that matters.

REFERENCES

Azzimonti, M., & Fernandes, M. (2023). Social media

networks, fake news, and polarization. European Journal

of Political Economy, 76, 102256. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2022.102256

Choi, W. (2020). Older adultsʼ credibility assessment of

online health information: An exploratory study using an

extended typology of web credibility. Journal of the

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

88

Association for Information Science and Technology,

71(11), 1295–1307. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24341

Choi, W., & Stvilia, B. (2015). Web credibility assessment:

Conceptualization, operationalization, variability, and

models. Journal of the Association for Information

Science and Technology, 66(12), 2399–2414.

https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23543

Chong, B., Yang, Z., & Wong, M. (2003). Asymmetrical

impact of trustworthiness attributes on trust, perceived

value and purchase intention: A conceptual framework

for cross-cultural study on consumer perception of online

auction. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference

on Electronic Commerce, 213–219. https://doi.org/

10.1145/948005.948033

Clark, R. C., & Lyons, M. (2004). Graphics and learning: The

role of illustrations, diagrams, and photographs in

complex learning tasks. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 96(1), 157-168.

Dam, T. C. (2020). Influence of Brand Trust, Perceived

Value on Brand Preference and Purchase Intention. The

Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business,

7(10), 939–947. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol

7.no10.939

Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is

beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 24(3), 285–290. https://doi.org/10.1037 h0

033731

Finn, A., Schrodt, P., Witt, P., Elledge, N., Jernberg, K., &

Larson, L. (2009). A Meta-Analytical Review of Teacher

Credibility and its Associations with Teacher Behaviors

and Student Outcomes. Communication Education -

COMMUN EDUC, 58, 516–537. https://doi.org/

10.1080/03634520903131154

Fogg, B. J. (2003). Prominence-interpretation theory:

Explaining how people assess credibility online. CHI ’03

Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, 722–723. https://doi.org/10.1145/765891.765

951

Fogg, B. J., Soohoo, C., Danielson, D. R., Marable, L.,

Stanford, J., & Tauber, E. R. (2003). How do users

evaluate the credibility of Web sites? A study with over

2,500 participants. Proceedings of the 2003 Conference

on Designing for User Experiences, 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1145/997078.997097

Ghai, A., & Tandon, U. (2022). Analyzing the Impact of

Aesthetic Visual Design on Usability of E-Learning: An

Emerging Economy Perspective. Higher Learning

Research Communications, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.188

70/ hlrc.v12.i2.1325

Gray, K., Knobe, J., Sheskin, M., Bloom, P., & Barrett, L. F.

(2011). More Than a Body: Mind Perception and the

Nature of Objectification. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 101(6), 1207–1220.

Hancock, D. J. (2004). Improving the Environment in

Distance Learning Courses Through the Application of

Aesthetic Principles. https://www.semanticscholar.org/

paper/Improving-the-Environment-in-Distance-Learnin

g-the-Hancock/8af1ea310dbd393f896ad241e3155936b

2a513ea

Harrison, L., Reinecke, K., & Chang, R. (2015). Infographic

Aesthetics: Designing for the First Impression.

Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1187–1190.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702545

Köhler, W. (1967). Gestalt psychology. Psychologische

Forschung, 31(1), XVIII–XXX. https://doi.org/10.1007/

BF00422382

KPMG. (2015). Corporate Digital Learning—How to Get It

“Right” [https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/

pdf/2015/09/corporate-digital-learning-2015-KPMG]

Lidwell, W., Holden, K., & Butler, J. (2010). Universal

Principles of Design, Revised and Updated: 115 Ways to

Enhance Usability, Influence Perception, Increase

Appeal, Make Better Design ... Design Decisions, and

Teach through Design (Revised edition). Rockport.

Lindgaard, G., Fernandes, G., Dudek, C., & Brown, J. (2006).

Attention web designers: You have 50 milliseconds to

make a good first impression! Behaviour & Information

Technology, 25(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/01

449290500330448

Lohr, L. L. (2007). Creating Graphics for Learning and

Performance: Lessons in Visual Literacy (2nd edition).

Pearson.

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia Learning. Cambridge

University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO97811391

64603

Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., Eyal, K. K., Lemus, D. R., &

Crawford, A. (2013). Credibility judgments of online

information sources: A comparison of cognitive and

heuristic processing approaches. Communication

Research, 40(5), 559-584.

Moshagen, M., & Thielsch, M. T. (2010). Facets of visual

aesthetics. International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, 68(10), 689–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.ijhcs.2010.05.006

Papachristos, E., Tselios, N., & Avouris, N. (2005). Inferring

Relations Between Color and Emotional Dimensions of

a Web Site Using Bayesian Networks. In M. F. Costabile

& F. Paternò (Eds.), Human-Computer Interaction—

INTERACT 2005 (pp. 1075–1078). Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/11555261_108

Research and Markets. (2023). E-Learning: Global Strategic

Business Report - Research and Markets.

https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/2832322/

e-learning-global-strategic-business-report

Rieh, S. Y. (2010). Credibility and Cognitive Authority of

Information. In Encyclopedia of Library and Information

Sciences (3rd ed., pp. 1337–1344).

Rock, I., & Palmer, S. (1990). The Legacy of Gestalt

Psychology. Scientific American, 263(6), 84–91.

Saw, C. C., & Inthiran, A. (2022). Designing for Trust on E-

Commerce Websites Using Two of the Big Five

Personality Traits. Journal of Theoretical and Applied

Electronic Commerce Research, 17(2), Article 2.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17020020

Singh, N., & Srivastava, S. K. (2011). Impact of Colors on

the Psychology of Marketing—A Comprehensive over

View. Management and Labour Studies, 36(2), 199–209.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600206

Aesthetics as a Decisive and Motivational Factor for Online Training

89

Suriadi, J., Mardiyana, M., & Reza, B. (2022). The concept

of color psychology and logos to strengthen brand

personality of local products. Linguistics and Culture

Review, 6(S1), Article S1. https://doi.org/10.21744/

lingcure.v6nS1.2168

Todorovic, D. (2008). Gestalt principles. Scholarpedia,

3(12), 5345. https://doi.org/10.4249/scholarpedia.5345

Tractinsky, N., Katz, A. S., & Ikar, D. (2000). What is

beautiful is usable. Interacting with Computers, 13(2),

127–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-5438(00)0003

1-X

Wilson, P. (1983). Second-Hand Knowledge: An Inquiry Into

Cognitive Authority. Greenwood Press.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

90