Piloting Case Studies of Technology-Enhanced Innovative Pedagogies

in Four European Higher Education Institutions

Blaženka Divjak

a

and Josipa Bađari

b

Faculty of Organization and Informatics, University of Zagreb, Pavlinska 2, Varaždin, Croatia

Keywords: Hybrid Teaching, Flipped Classroom, Higher Education, Professional Development.

Abstract: This study investigates the implementation and effects of innovative pedagogical practices in higher education

across four European countries: Croatia, Finland, Portugal, and Spain. The research centres on 40 educators

and encompasses a variety of advanced teaching approaches, including flipped classrooms, project-based,

problem-based, inquiry-based, and team-based learning. It also assesses the transition to different modes of

delivery such as blended, hybrid, and online education, along with the inclusion of entrepreneurial

competencies. The primary focus is on understanding educators' experiences and challenges in adopting these

innovative methods during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The research was conducted over the academic

year 2022/2023, employing a methodology designed to reflect real-life implementation of redesigned courses.

Data were collected through an anonymous feedback survey from educators involved in piloting, which

included responses from 90% of the educators. It included the self-reflection of educators based on the

documented journals and their summarised view of students’ perspectives. Availability of technology and

training opportunities for educators enhanced the use of innovative teaching and learning approaches. The

results indicate that with appropriate support in redesigning their courses, educators found the innovative

approaches to be effective and potentially sustainable.

1 INTRODUCTION

Advancements in technology have brought far-

reaching impacts to educational delivery. The use of

technologies has become essential in a broad range of

pedagogical activities and promoted the development

of new modes of education. (Wong et al., 2022)

review that there has been an increasing trend in the

amount of work on hybrid learning and teaching over

the past decade. In response to COVID-19 pandemic

lockdowns, hybrid learning and teaching have been

widely adopted as a substitution for the face-to-face

approach. Such a sudden shift in the mode of

educational delivery has also contributed to the rapid

development of this emerging learning and teaching

mode (Li et al., 2023).

On the other hand, the growth of the need to

improve entrepreneurship education developing skills

necessary for the labour market has challenged

educators to reconsider what to teach and how to

teach (Canziani et al., 2015; Fiet, 2001), and how to

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0649-3267

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-1289-6748

include innovative teaching and become more

entrepreneurial in their teaching (Peltonen, 2015).

Research results presented here were conducted

during 2022 and 2023 within Erasmus+ project e-

DESK – Digital and Entrepreneurial Skills for

Teachers implemented in the period 2021-2023. Its

main objective was to provide European HE

educators with the required digital skills and

entrepreneurial mind-set to succeed in the 21st

century teaching environment. The project included

the expertise of four European universities

(University of Cantabria (UC), NOVA University of

Lisbon (NOVA), University of Zagreb (UZ),

Lappeenranta-Lahti University of Technology

(LUT)) and the International Entrepreneurship Centre

of Santander (project coordinator) in online training,

curricula design and entrepreneurship education.

(OECD, 2009) states that it is useful to distinguish

between teaching competences and educator

competences and understanding the importance and

the necessity of both for the 21ct educators and e-

Divjak, B. and BaÄ

´

Sari, J.

Piloting Case Studies of Technology-Enhanced Innovative Pedagogies in Four European Higher Education Institutions.

DOI: 10.5220/0012619300003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 371-379

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

371

DESK project was focused on the innovative

combination of the established pedagogies (Peterson

et al., 2018) as active learning accelerators, as well as

a successful enabler for the development of digital

and entrepreneurship skills of educators described in

the EntreComp (Bacigalupo et al., 2016), a common

reference framework that identifies 15

entrepreneurial competences in 3 key areas. The

novelty within the project was based on the goal to

research and pilot how the development of

entrepreneurial competences can be integrated in

teaching and learning activities using novel

pedagogical approaches. At the beginning of the e-

DESK in 2021 the state-of-the art survey was

performed among educators from the e-DESK partner

countries to find out more about the experiences of

HE educators with the shift to digital teaching during

the COVID-19 pandemic (Svetec et al., 2022). The

study found the portion of educators fully using ICT

was almost three times higher than before the

pandemic but also that some innovative pedagogies

were not used to their full potential. About more than

a half participants (56.3%) found their organization

needed to offer more support to improve online

teaching.

Since designing, implementing, and assessing

learning experiences in hybrid, blended, or fully

online delivery modes can be a transformative

journey for both educators and students if it goes hand

in hand with implementation of innovative

pedagogies, e-DESK offered key considerations and

strategies for designing effective learning

experiences, successful implementation, and

monitoring with respect that successful

implementation requires continuous reflection,

adaptation, and improvement (e-DESK, 2023).

Also, the project was delivered within the

acknowledgement that as education continues to

evolve, it is essential to embrace the possibilities

offered by hybrid, blended, and fully online delivery

modes since these modes provide opportunities for

personalized learning, collaboration, and self-

directed exploration.

(OECD, 2022) reports that a lack of ICT skills

continues to be one of the key barriers keeping people

from fully benefiting from the potential of digital

technologies, including opportunities for online

learning. Most OECD countries found resources to

purchase digital tools for in-classroom and remote

learning and to train educators in their use which was

a big step in the right direction, but they did not go far

enough. To fully benefit from digitalisation, the

innovation culture must be strengthened in education.

Based on the objectives of the e-DESK project

and performed activities, the aim of the study is to

answer the following research questions: RQ1: What

is the experience of educators introducing innovative

pedagogies during and post-COVID higher education

(HE)?; RQ2: Did available technology and

professional development increase the use of

innovative teaching approaches and/or vice versa?

RQ3: Were there any country-related differences in

reported piloting experiences?

2 BACKGROUND

As seen by (Pischetola, 2022) the sudden

digitalisation that occurred with the COVID-19

pandemic has shown us that one of the most complex

and daunting challenges for HE educators is

managing the ongoing transformation of learning

environments.

This entails identifying emerging technologies

and platforms (EdTech) with potential relevance for

teaching and customisation and providing students

with high-quality learning experiences (Rapanta et al.

2020; Ní Shé et al., 2019). It also requires institutional

and organizational strategies to foster educator

sensitivity to expanded possibilities beyond space–

time boundaries (McGregor, 2003) and conventional

face-to-face lectures (Hodges et al., 2020).

What regards the modes of delivery, as analysed

by (Ulla and Perales, 2022) the literature presents no

clear definition of hybrid teaching, its differences

from other modes of lesson delivery (e.g., blended

learning), and how such teaching methodology was

conducted in the teaching and learning environment,

especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Very

often studies used the concept of hybrid

interchangeably with blended learning (O’Byrne and

Pytash, 2015; Klimova and Kacetl, 2015; Solihati and

Mulyono, 2017; Smith and Hill, 2019), emphasizing

the combination of classroom instruction with online

instruction. However, in the context of e-DESK

project we distinguish between hybrid, blended and

online learning, in line with (Svetec et al., 2022)

where hybrid mode of teaching considers that

students are simultaneously present in the same

classroom, either physically or remotely. It means

that an educator is working simultaneously with a

group of students physically present in a classroom,

and those present remotely via a conferencing system.

The use of innovative pedagogies hand in hand

with the hybrid and fully online teaching was of

particular interest during the pandemic. For

innovative pedagogies such as flipped classroom

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

372

(FC), literature findings indicated that those who had

used FC approaches in face-to-face or blended

learning environments more successfully continued

to use them in online environments than those who

had not used it before (Divjak et al., 2022).

Furthermore, in the context of e-DESK project,

hybrid learning modes and active learning methods

that ask students to engage in their learning by

thinking, discussing, investigating, and creating and

where they practice skills, solve problems, make

decisions, propose solutions is important for the

development of entrepreneurial competences.

(Joensuu-Salo et al., 2021) state that educators, as

entrepreneurship educators, are acknowledged to play

a significant role in developing entrepreneurial ways

of thinking and acting in students.

Therefore, and based on EntreComp framework,

project e-DESK created a free and open e-DESK

MOOC in 10 units aiming to support educators on the

development of digital and entrepreneurial

competences for the implementation of digital tools,

and innovative pedagogical techniques in their

classrooms. During 2022, 40 educators from e-DESK

partner institutions used this MOOC to prepare

themselves for the piloting of redesigned courses:

https://edeskeurope.eu/e-desk-mooc/.

3 PILOT METHODOLOGY

3.1 Sampling and Instrumentation

The main aim of the e-DESK piloting performed

during the academic year 2022/2023 was to

experiment with the methodology developed within

the project in real-life educational situations.

The educators were selected at partner institutions

in a piloting group helping the e-DESK team validate

the methodology and training scheme (e-DESK

MOOC) developed for this project. The selection

process was conducted as an open call for all interested

educators. The suggested optimal number was 10

educators/pilots per involved educational institution

(4).

The piloting data collection instrument was

developed (recommended diary and final survey, both

for qualitative and quantitative data collection) within

project partner meetings and tested on a small sample.

The piloting was divided into three different

phases focused on: preparation of the learning design

(Phase 1), support in the delivery and monitoring of

the designed courses (Phase 2), and guidance through

the evaluation and reporting of the experience (Phase

3). Educators were supported in their design and

implementation work within regular workshops and

meetings at the beginning/end of each phase, as well

as via e-DESK MOOC.

3.2 Demographic Features

The piloting data was collected anonymously after the

piloting and received from 90% of the educators

involved in piloting (36/40). It included 10 responses

from LUT (Finland), 9 from NOVA (Portugal), 6 from

UC (Spain) and 11 from the UZ (Croatia). (see 4.3)

The piloting courses were planned (Phase 1) using

the following methods/tools: 20 Balanced Design

Planning (BDP) learning design tool, 10 spreadsheet

planning, 4 other design tools, 2 without design tools.

Within 36 pilots the educators reported the following

modes of delivery: 51 blended deliveries, 46 hybrid, 16

fully online and 10 other modes of delivery (see 4.2).

In addition, different methodological approaches

have been implemented in the pilots: 21 reported

entrepreneurial competencies development, 19

flipped classroom method, 17 project-, 19 problem-

based learning, 27 team-based learning while 10

included inquiry-based learning and 10 other (e.g.

Joint Creative Classrooms, Gamification Labs)

approaches. Regarding the number of the involved

educators and students: besides the responding

educator, each pilot mainly (n=17) involved 1

additional educator, 9 pilots were performed by a

single educator, 7 with 3 educators, and there were 1

pilot examples with 4, 5 and 5+ educators; all courses

together included more thousands of students in the

following ranges: 4 courses with 6-10 students, 3 with

11-15 students, 5 with 16-20 students, 6 with 20-30

students, 11 with 30-100 students, 6 with 100-300

students and 1 course with 300+ students.

3.3 Data Collection

Data was collected in the academic year 2022/2023

with the Ethical Approval of the Ethical Committee

of the Faculty of Organization and Informatics,

University of Zagreb. The instrument was used for

final data collection and was distributed

electronically by each project partner among their

educators. The conducted research was not

experimental design research and therefore it did not

include a control group.

3.3.1 Qualitative Data

Educators were instructed to take journal notes on

how they have proceeded in the learning design

process (Phase 1). The process included the selection

Piloting Case Studies of Technology-Enhanced Innovative Pedagogies in Four European Higher Education Institutions

373

of the suitable course or course part and topic(s),

selecting and better defining the learning outcomes,

used technologies, delivery modes etc. Also, they

were advised to make notes about the experience in

using the e-DESK MOOC and learning design tools.

During the implementation (Phase 2), educators

took notes on how designed activities succeeded (e.g.

did the technology and delivery mode work as

planned, did the planned assignments work as

planned, were the learning outcomes achieved and

what feedback came from students to educator(s)).

3.3.2 Quantitative Data

Qualitative data included student grades (where

available) and the digital footprint in LMS

(participation, engagement, time-on-task, the number

of students taking part in activities). In some cases, it

included the questionnaires for students, with close-

and open-ended questions, related to course delivery.

The data was collected and analysed (Phase 3) in

collaboration and with the guidance of the

institutional project coordinator. The reporting

process, important to close the improvement cycle,

was done using an online questionnaire (see 4

Results) which guided educators to summarize

specific quantitative and qualitative data collected

and prepared throughout the piloting.

4 RESULTS

In this study, we focus on educators’ perspective

within e-DESK piloting, taking into account the

different national contexts and teaching areas in

which the pilots were performed.

The results include the analysis of the answers

from 36 pilots (90% of all included) provided by

educators involved in the pilot. Since the context of

the project allowed that one educator performs

multiple different pilots, the feedback was gathered

by pilots (redesigned courses) and not by educators.

Besides general questions about the institution,

modes of course delivery, course planning tool and

used innovative approaches, the instrument included

12 statements developed by the e-DESK project team.

The answers were collected as the feedback based on

the Likert scale (5 Fully Agree -1 Fully Disagree).

Educators’ answers were based on their monitoring of

a learning design orchestration.

4.1 General Results

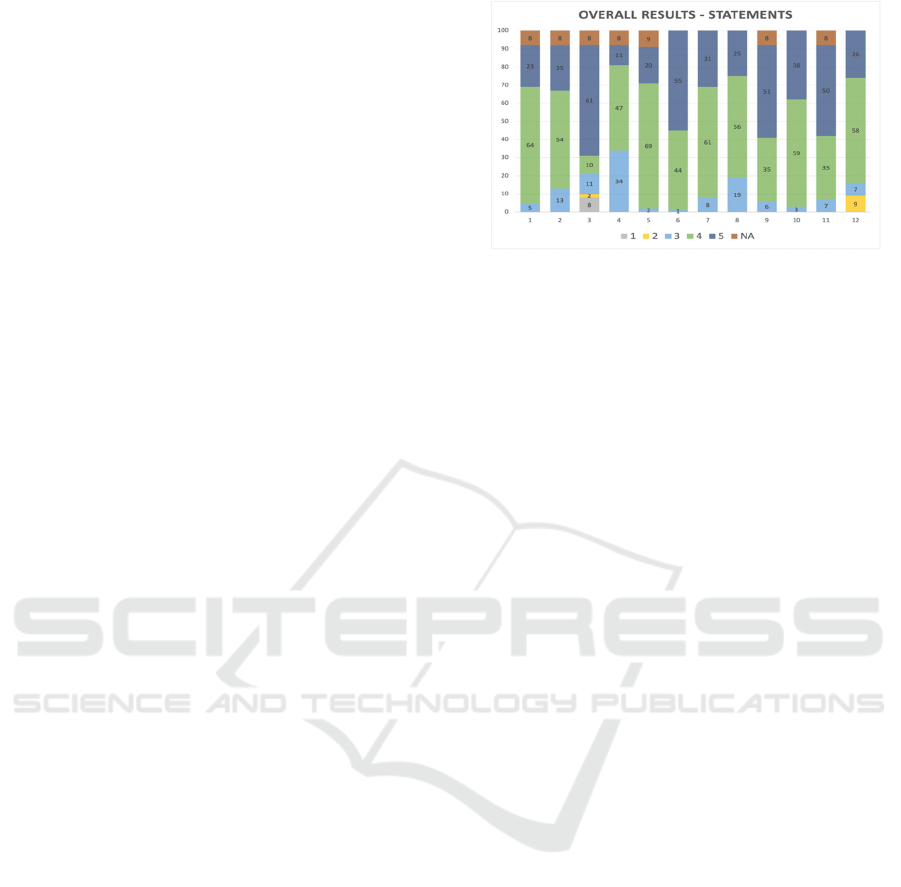

The following overall feedback was received:

Figure 1: Overall results (%).

Statement 1 - I defined the learning outcome for pilot

delivery without significant difficulties: 64%

educators agree and 23% fully agree with the

statement.

Statement 2 - I adapted teaching and learning

activities to align with pilot goals without significant

difficulties: 54% of educators agreed and 25% fully

agreed with the statement.

Some negative answers were received within

statement 3 - I had sufficient access to technical

infrastructure within my University/department: 8%

of educators completely disagreed and 2% disagreed.

However, 61% of educators fully agreed with the

statement, only 10% agreed with the statement while

11% neither agreed nor disagreed. Further research

revealed that the disagreement is mostly present in

one organization while other educators have positive

experiences.

Regarding students’ perspective: in statement 4 -

I perceived the students' engagement in the chosen

mode of delivery higher than before: 34% of

educators stated that they neither agree nor disagree

and 47% stated that they agree while 8% of them find

the statement not applicable. Further, within

statement 7 - I perceive this pilot supported my

students in better achieving intended learning

outcomes: 61% of educators agreed with the

statement and 31% fully agreed. Very similarly

within statement 8 - I perceive the interest of my

students towards the piloted subject has increased:

56% of educators agreed and 25% fully agreed with

the statement while 19% of them neither agreed nor

disagreed.

Within statement 5 - I find the support for pilot

delivery provided within e-DESK MOOC useful: 69%

agreed with the statement, 20% fully agreed while 2%

neither agreed nor disagreed or found the statement

not applicable (9%).

What regards educators’ future intentions: within

statement 6 - I find this pilot helpful for my future

teaching delivery: 55% of educators fully agreed,

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

374

while 44 agreed, and 2% neither agreed nor

disagreed. Further, within statement 9 - I am planning

to include this delivery mode in my future teaching:

51% of educators fully agreed, 35% agreed while

others neither agreed nor disagreed (6%) or found the

statement not applicable (8%). In further research

results (below) we state the distribution of future

intentions of the included educators by delivery

modes.

Regarding the pilot success and relevance, within

statement 9 - I find the pilot overall successful: 58%

of educators agreed and 38% fully agreed with the

statement. Very similarly, within statement 11 - I find

this pilot relevant to my institution: 54% of educators

fully agreed and 39% agreed.

Finally, the educators were asked to provide

feedback on the requested workload within statement

12 - I find my workload invested into this pilot

justified by the results. Although 9% disagreed with

the statement, 26% of educators completely agreed

and 58% agreed.

4.2 Results per Delivery Mode

The educators included in the piloting were free to

decide which of the recommended delivery modes

they piloted and their choice was based on their

personal and institutional preferences.

4.2.1 Blended

The piloting experiment included 51 blended

experiences, 30 of which have been planned within a

collaborative BDP tool, 13 by using spreadsheet

planning and 8 by using other design tools.

Regarding the included competences or new

pedagogical approaches, the educators reported the

use of: 9 developing entrepreneurial competencies,

10 FC, 6 Inquiry-based learning, 8 problem-based

learning, 5 project-based learning, 11 team-based

learning and 2 other. All approaches were more or

less used by educators from all involved institutions

with the exception of the educators from NOVA that

minimally used FC and inquiry-based learning (1

example).

The institutions using a blended mode of delivery

included: UZ (17), LUT (16), UC (15) and NOVA (3)

with the following number of educators: the majority

of courses included 2 (23) and 3 educators (12) or

single educator (9), and other courses had 5 (3) or 6+

educators (4). Regarding the class sizes: 14 deliveries

included 100-300 students, 16 included 30-100, 5

included16-20, 6 included 20-30, and 10 included 6-

10 students.

Educators reported great satisfaction that the

workload invested into this pilot was justified by the

results: 10% fully agreed, 75% agreed and 15%

neither agreed, nor disagreed; as well as high level of

the intention of further use of blended delivery since

49% of educators reported to fully agreed and 31%

agreed to continue with blended delivery.

4.2.2 Hybrid

The piloting experiment included 52 hybrid

experiences, 30 of which have been planned within a

collaborative BDP tool, 20 by using spreadsheets for

planning and 2 without a tool.

Regarding the included competences or new

pedagogical approaches, the educators reported: 7

developing entrepreneurial competences, 8 FC, 3

inquiry-based learning, 9 problem-based learning, 9

project-based learning, 11 team based learning and 5

other, not listed.

Institutions using hybrid mode of delivery

included: UZ (24), NOVA (20), UC (6) and LUT(2)

while the majority of courses included 2 and 3

educators (17) or single educator (11), and other

courses had 4 (3) or 6+ educators (4).

Hybrid teaching was not dependant on the class

size since in 3 deliveries 300+ students were

involved, in 6 deliveries 100-300, in 13 deliveries 30-

100, in 9 deliveries 16-20, in 8 deliveries 23-30 in 4

deliveries 11-15 and in 3 deliveries 6-10 students.

What regards the educator satisfaction about the

workload invested into hybrid pilot justified by the

results: 52% fully agreed, 40% agreed and 8% neither

agreed, nor disagreed which is in line with the

intention to further use the hybrid teaching since 62%

of educators fully agreed that they are planning to

include hybrid delivery mode in their future teaching,

23% agreed and 6% neither agreed nor disagreed with

the statement. Others found the statement not

applicable (9%).

4.2.3 Online

The piloting experiment included 17 fully online

experiences, 15 of which have been planned mainly

planned within a collaborative BDP tool (15).

Regarding the included competences or new

pedagogical approaches, the educators reported: 4

developing entrepreneurial competences, 2 Inquiry-

based learning, 2 problem-based learning, 2 project-

based learning, 3 team based learning and other 4.

Educators did not report the use of flipped classroom

method in fully online teaching.

Institutions using a fully online mode of delivery

included: LUT (12), UZ (4) and NOVA (1). The

Piloting Case Studies of Technology-Enhanced Innovative Pedagogies in Four European Higher Education Institutions

375

educators from UC did not report using a fully online

mode of delivery.

The majority of courses included 1 educator (10)

or 2 educators (6), and only 1 course reported 3

included educators. There were no fully online

courses with 4 or more educators with the following

number of students - 1 course included 100-300

students, 5 included 30-100 students, 4 included 20-

30 students and there were 7 courses with 11-15

students. The fully online teaching was not used with

300+ groups nor with the groups including 10 or less

students.

The educators fully agreed that the workload

invested into the online was justified by the results

(12%), or agreed (59%), while 6% neither agreed, nor

disagreed and 23% disagreed.

Despite high disagreement with the workload,

59% of educators reported to fully agree and 41%

agree to deliver online teaching in future.

4.2.4 Other

The educators in piloting experiment from UZ (4) and

UC (6) also reported the use of other modes of

delivery, usually together with the above listed

options (e.g. gamification labs, technology enhanced

learning…) These courses mainly included 2 (6) or 1

educator (4) and smaller groups of students (20-30 -

6 courses; 6-10 - 4 courses).

What regards the included teaching methods, the

piloting experiences were diverse: 1 included

developing entrepreneurial competences, 2 flipped

classroom, 1 problem-based, 2 project based and 3

team-based teaching and learning. These courses

were planned by use of BDP tool (4), other design

tools (4) or without a tool (2).

All educators (100%) agreed that they will

continue to practice that kind of teaching.

4.3 Results per Institutions

Overall, the educators from LUT, Finland (n=10)

created 30 piloting experiences and found the piloting

experience positive. The statement where they

disagree most is statement 4 - I perceived the students'

engagement in chosen mode of delivery higher than

before where the majority of educators (66%) neither

agree nor disagree while 33% agree. Regarding

further use, 53% of LUT educators fully agree and

40% agree that they are planning to include piloted

delivery mode in their future teaching. The educators

from LUT were mainly (53%) using blended delivery

mode and online mode (40%) with the following

learning approaches: Developing entrepreneurial

competences (30%), team-based learning (27%),

problem-based learning (13%) and inquiry-based

learning (10%). Only in one piloting experience (3%)

they used the flipped classroom approach. Regarding

the learning design of the piloted courses, 87% of the

educators from LUT reported to have used the BDP

collaborative design tool, and 13% to have used other

design tools.

Educators from FOI, Croatia (n=11) created 49

piloting experiences and were the most positive with

the piloting experience and the most positive in

statement 3 - I had sufficient access to technical

infrastructure within my University/department

where 78% of educators fully agreed while 2% agreed

and 10% found the statement not applicable.

Regarding further use, in 43% of piloting experiences

educators fully agreed and in 37% agreed that they

are planning to include piloted delivery mode in their

future teaching while 20% consider the statement not

applicable. Educators from FOI reported to use all

delivery modes: hybrid (49%), Blended (35%), online

(8%) and other (8%) combined with the following

innovative approaches: problem (20%) and project

based learning (20%), flipped classroom (16%),

team-based learning (16%), inquiry based learning

(12%), developing entrepreneurial competences

(8%).

Educators from UC Spain (n=6) created 27

piloting experiences and also expressed very positive

and useful piloting experience with unanimous

agreement within statement 12 - I find my workload

invested into this pilot justified by the results.

However, although the piloting instructions, as well

as e-DESK MOOC included the strong suggestion for

educators to use a learning design tool (e.g.

collaborative BDP tool), only 33% of piloting

experiences designed by the educators from Spain

was designed via a design tool (and never via a

collaborative BDP tool). Regarding further use the

educators from Spain were extremely positive and

60% of them fully agreed and 40% agreed that they

are planning to include piloted delivery mode in their

future teaching. They reported the use of the

following delivery modes: blended (56%), hybrid

(22%) and other (22%) combined with the following

innovative approaches: flipped classroom (30%),

team-based learning (22%), developing

entrepreneurial competences (11%), problem (11%)

and project based learning (11%), as well as inquiry

(3%) and other (Technology Enhanced Learning,

Gamification) approaches (11%).

Educators from NOVA, Portugal (n=9), although

giving very positive feedback on most of the

statements, 50% disagree with the statement 3 - I had

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

376

sufficient access to technical infrastructure within my

University/department. Also, they show strong

agreement with statement 6 - I find this pilot helpful

for my future teaching delivery and statement 9 - I am

planning to include this delivery mode in my future

teaching. Only 17% of piloting experiences by

NOVA educators were designed with the support of

the tool (collaborative BDP tool).

Regarding further use, in 58% of piloting

experiences educators fully agreed and in 17% agreed

that they are planning to include piloted delivery

mode in their future teaching.

Also for 63% piloting experiences educators fully

agreed and for 27% agreed that the workload invested

into pilot was justified by the results. Educators from

Portugal reported the following deliveries: blended

(13%), hybrid (83%) and online (4%) combined with

the following innovative approaches: flipped

classroom (13%), team-based learning (25%),

developing entrepreneurial competences (21%),

problem (13%) and project based learning (17%), as

well as inquiry (4%) and other approaches (8%).

5 DISCUSSION

Considering the above presented results, and

regarding the RQ1 it is evident that the educators and

institutions have made a successful effort at planning

and piloting their courses in including innovative

pedagogies, and supporting development of digital

and entrepreneurial skills of educators and students.

The educators followed all planned

implementation phases, gathered quantitative and

qualitative data about the orchestration of a learning

design, as well as about the student satisfaction and

achievement of learning outcomes, and provided

feedback on their experience. The results confirmed

that the guidance provided within the e-DESK project

and the peer support had a positive impact on the

educators’ satisfaction and they expressed that the

piloting experience helped them deciding to include

innovative pedagogical methods and non-traditional

modes of delivery in their future teaching. It seems

that provided training made them comfortable with

the use of learning outcomes and constructive

alignment (Biggs, 1996) in LD, which have been

recognized as challenging for educators (Goodyear,

2020).

Furthermore, the positive attitude of the educators

reflects in the fact that 86% of them in total perceived

the invested efforts being justified by the results, but

also that they planned to use innovative approaches

and technology-supported delivery mode in the

future.

Structured feedback on the learning design related

to the intended learning outcomes was available only

to those educators using the planning tools (70%). As

stated above, the educators were encouraged to use

such tools and especially the collaborative BDP tool

(RQ2).

Croatian educators reported the highest

satisfaction with technical infrastructure, the highest

satisfaction with the pilots, as well as the willingness

to use new approaches in the future. This supports the

claim that infrastructure and peer-learning is a

necessary condition for pedagogical innovation and

sustainability (Rapanta et al., 2021)(RQ2).

Regarding RQ3, this piloting confirmed once

again that the education innovation is both a

pedagogic and organizational challenge approached

differently in different countries (OECD, 2016).

Related to the mode of delivery, blended and

hybrid were more popular choices than fully online.

This is in line with the institutional strategies because

involved institutions are primarily campus-based and

encourage technology-enhanced teaching and

learning. There are country-related differences with

Finnish educators preferring online delivery while the

hybrid delivery was mainly used by educators from

Croatia (RQ3).

Educators used a variety of pedagogical

approaches, mostly flipped classroom (FC), project-,

problem-, team- and inquiry-based learning.

Interestingly, educators did not report the use of FC

in online delivery while FC was a very popular choice

in blended and hybrid delivery. This can be linked to

the earlier research results (Divjak et al., 2022) or due

to teaching tradition at an institution and previous

training in certain pedagogical approaches required

by institutional or national authorities (RQ3). Finally,

the highest level of satisfaction with the results, as

well as with the workload invested into this pilot,

expressed the educators with hybrid delivery

experiences.

Differences regarding the organizational support

relate to the conclusion of the (Svetec et al., 2022)

conducted within e-DESK prior to the piloting stating

more than a half (56.3%) found their organization

needed to offer more support to improve online

teaching. Within this research, the participants from

Portugal reported that the received access to the

needed institutional infrastructure did not meet their

expectations while other participants mainly agreed

about the sufficient access to technical infrastructure

within their institutions. The limitation of the research

is that the sample is too small to generalize but it will

Piloting Case Studies of Technology-Enhanced Innovative Pedagogies in Four European Higher Education Institutions

377

be useful in future research to relate the level of

support and infrastructure availability to the use of

mode of delivery.

Furthermore, regarding the students' engagement

being higher than before course re-design, the

majority of educators from Finland (80%) neither

agreed nor disagreed with the statement, while the

educators from other countries mainly reported

agreement with the statement. The answers to this

statement were based on students’ questionnaires and

sometimes on the educators’ personal observations

and prior teaching experience. This means

evaluations were also dependent on the usual levels

of students’ engagement in different national

education systems, as well as on their prior

experience with different teaching modes and

innovative teaching approaches. Further, since there

was no unified student satisfaction survey created

within the e-DESK project, it can be considered as a

limitation since the student experience data was

gathered by educators according to their preferences.

Moreover, preferences and willingness to use

structured approach to learning design also varied

(RQ3). The acceptance of the BDP tool was the

highest in Croatia and Finland and the lowest in Spain

and Portugal. These differences can be rooted in the

institutional approaches to learning design and

recommended tools at different institutions. On the

other hand, explicitly recognizing development of

entrepreneurial competences was the highest among

the educators from Finland and Portugal and reason

might been in previous stronger promotion of their

importance on institutional level. However, one of the

e-DESK project goal was to strongly promote the fact

that the entrepreneurial competences can be

developed by use of innovative pedagogical

approaches (e.g. problem-, project and team-based

learning) and we can notice that there are many

learning designs that incorporated both.

To summarize, the limitation of this research

include the size of the sample since larger sample and

a wider range of participants may have elicited

different results. Furthermore, collecting more data

directly from the students about the quality of

learning design and implementation of new

pedagogical approaches, as well as about the students'

grades might shed more light on the results and

interpretation of it.

Finally, studying organizational culture and in-

depth analysis of infrastructure availability and

opportunities for professional development can more

firmly support claims related to RQ2. These

limitations can also pave the avenues for further

research.

6 CONCLUSION

This study sheds light on the integration of innovative

technology-enhanced pedagogical practices and

especially those that support development of

entrepreneurial competences (e.g. project-based

learning, team work) in HE within four European

countries.

The experiences of educators in transitioning to

hybrid, blended, or online modes of delivery reveal

advancements in achieving learning outcomes and

generating student interest for their courses.

However, challenges persist in enhancing active

student engagement through these innovative

methods. Educators preferred blended and hybrid

modes of delivery to fully online or face to face.

A key finding is the positive impact of structured

support, including professional development and

learning design planning tools, on educators'

willingness to embrace and sustain new teaching

approaches. The variations in preference for delivery

modes among institutions highlight the importance of

contextual factors, such as institutional strategy, peer

learning and technical infrastructure, in the successful

adoption of these methods.

While the study identifies a general readiness

among educators to continue using innovative

approaches, it also underscores the need for continued

support and respected resources to ensure long-term

sustainability and effectiveness of innovations.

Future research should focus on expanding the

scope of participants and incorporating more detailed

analyses of organizational culture and infrastructure,

which are crucial in understanding the dynamics of

pedagogical innovation in HE.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was conducted within the project e-DESK:

Digital and Entrepreneurial Skills for European

Teachers, financed from the Erasmus+ Programme of

the European Union. The sole responsibility for the

content of this article lies with the authors. It does not

necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Union.

REFERENCES

Bacigalupo M, Kampylis P, Punie Y and Van Den Brande

L. (2016) EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Compe-

tence Framework. EUR 27939 EN. Luxembourg

(Luxembourg): Publications Office of the European

Union; 2016. JRC101581

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

378

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive

alignment. Higher Education 32, 347-364

Canziani B, Welsh DHB, Hsieh Y, et al. (2015) What

pedagogical methods impact students’ entrepreneurial

propensity? Journal of Small Business Strategy 25(2):

97–113.

Divjak, B., Grabar, D., Svetec, B. & Vondra, P. (2022)

Balanced Learning Design Planning: Concept and Tool.

Journal of information and organizational sciences, 46

(2), 361-375 doi:10.31341/jios.46.2.6.

Divjak, B., Rienties, B., Iniesto, F., Vondra, P., & Žižak, M.

(2022). Flipped classrooms in higher education during

the COVID-19 pandemic: findings and future research

recommendations. International Journal of Educational

Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 9.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00316-4

eDESK Toolkit/Guide for Educators. (2023)

https://edeskeurope.eu/edesk-tools/

Fiet J. (2001) The pedagogical side of entrepreneurship

theory. Journal of Business Venturing 16: 101–117.

Goodyear, P. (2020), Design and co-configuration for

hybrid learning: Theorising the practices of learning

space design. Br J Educ Technol, 51: 1045-1060.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12925

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A.

(2020). The difference between emergency remote

teaching and online learning. Educause Review, 27

March. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-

difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-

online-learning.

Joensuu-Salo, S., Peltonen, K., Hämäläinen, M., Oikkonen,

E., & Raappana, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial teachers do

make a difference – Or do they? Industry and Higher

Education, 35(4), 536-546. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0950422220983236

Klimova, B. F., and Kacetl, J. (2015). Hybrid learning and

its current role in the teaching of foreign languages.

Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 182, 477–481. doi:

10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.830

Li KC, Wong BTM, Kwan R, Chan HT, Wu MMF, Cheung

SKS. (2023). Evaluation of Hybrid Learning and

Teaching Practices: The Perspective of Academics.

Sustainability; 15(8):6780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su

15086780

Mcgregor (2003). Making Spaces: teacher workplace

topologies. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 11(3), 353-

377. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360300200179.

Ní Shé, C., Farrell, O., Brunton, J., Costello, E., Donlon, E.,

Trevaskis, S., & Eccles, S. (2019). Teaching online is

different: critical perspectives from the literature.

Dublin: Dublin City University.

O’Byrne, W. I., and Pytash, K. E. (2015). Hybrid and

blended learning. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 59, 137–140.

doi: 10.1002/jaal.463

OECD. (2009). Creating Effective Teaching and Learning

Environments. First Results from TALIS. Paris: OECD.

http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/17/51/43023606.pdf

OECD (2016), Innovating Education and Educating for

Innovation: The Power of Digital Technologies and

Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1787/9789264265097-en

OECD (2022), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD

Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/

10.1787/3197152b-en.

Peltonen, K. (2015) How can teachers’ entrepreneurial

competences be developed? A collaborative learning

perspective. Education + Training 57(5): 492–511.

Peterson, A., et al. (2018), "Understanding innovative

pedagogies: Key themes to analyse new approaches to

teaching and learning", OECD Education Working

Papers, No. 172, OECD Publishing, Paris,

https://doi.org/10.1787/9f843a6e-en.

Pischetola, M. (2022) Teaching Novice Teachers to

Enhance Learning in the Hybrid University.Postdigit

Sci Educ 4, 70–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-

021-00257-1

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., &

Koole, M. (2020). Online University Teaching During

and After the Covid-19 Crisis: Refocusing Teacher

Presence and Learning Activity. Postdigital Science

and Education, 2(3), 923–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s42438-020-00155-y

Smith, K., & Hill, J. (2019). Defining the Nature of Blended

Learning through Its Depiction in Current Research.

Higher Education Research & Development, 38, 383-

397. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1517732

Solihati, N., and Mulyono, H. (2017). A hybrid classroom

instruction in second language teacher education

(SLTE): a critical reflection of teacher educators. Int. J.

Emerg. Technol. Learn. 12, 169–180. doi:

10.3991/ijet.v12i05.6989

Svetec, B., Oksanen, L., Divjak, B. & Horvat, D. (2022).

Digital Teaching in Higher Education during the

Pandemic: Experiences in Four Countries. in: Vrček,

N., Guàrdia, L. & Grd, P. (ur.). Proceedings of the 33rd

Central European Conference on Intelligent

Information Systems (CECIIS).

Ulla MB and Perales WF (2022) Hybrid Teaching:

Conceptualization Through Practice for the Post

COVID19 Pandemic Education. Front. Educ.

7:924594. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.924594

Wong, B.T.M.; Li, K.C.; Chan, H.T.; Cheung, S.K.S. The

publication patterns and research issues of hybrid

learning: A literature review. In Proceedings of the 8th

International Symposium on Educational Technology,

Hong Kong, China, 19–22 July 2022; pp. 135–138.

Piloting Case Studies of Technology-Enhanced Innovative Pedagogies in Four European Higher Education Institutions

379