Crafting a Journey into the past with a Tangible Timeline Game: Net Als

Toen as a Tool to Enhance Reminiscence in Elderly with Alzheimer’s

Disease

Renske Mulder

1

, Puck Kemper

1

, Hannah Ottenschot

1

and Anis Hasliza Abu Hashim

1,2 a

1

Faculty of EEMCS, University of Twente, Drienerlolaan 5, Enschede, The Netherlands

2

Research Group Human Media Interaction, University of Twente, The Netherlands

Keywords:

Alzheimer’s Disease, Reminiscence Therapy, Interactive Games.

Abstract:

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) poses significant challenges for individuals and their caregivers due to its impact

on memory, behavior, and cognitive abilities. With the projected increase in AD cases in the coming years,

innovative technologies are needed to address the growing demand for elderly care and support for people with

AD. Reminiscence therapy (RT) can have positive effects on the rate at which AD symptoms worsen. This

paper presents an interactive game based on RT called Net Als Toen, which serves as a conversation starter. The

ideation phase, lo-fi prototype development, and hi-fi prototype testing are discussed. Results from playtests

show that the embedded reminiscence theory in Net Als Toen can help people with AD in talking about their

memories. Additionally, results suggest that personalization options and improved user interface elements are

important in making the application successful. Overall, this paper contributes to developing a social game

based on RT, focusing on interpersonal reminiscence therapy, to foster interactive conversations and enhance

the well-being of individuals with AD.

1 INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), a form of dementia, can

have a significant impact on someone’s life. It can

cause problems with memory and behavior, and cog-

nitive impairment. These symptoms can create chal-

lenges in caring for people who suffer from AD. More

and more people are expected to suffer from AD in

the upcoming years, with about 152 million people in

2050, compared to 58 million cases in 2019 (Nichols

et al., 2022). In the earlier stages of AD, memory

will often be affected most, making daily life more

difficult. In the later stages of the disease, this im-

pact can grow, which could also influence speech and

movement. These symptoms often lead to anxiety,

irritability, confusion, and frustration, which in turn

can greatly impact someone’s social life, isolating

them from others and increasing feelings of loneli-

ness (Balouch et al., 2019).

There is no cure yet to battle AD and its symp-

toms. However, the progression of AD can be slowed

down (Wimo et al., 2015; Anand and Singh, 2013;

Kaduszkiewicz et al., 2005) and some treatments are

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3204-5719

already available. There are medicine-focused ap-

proaches and non-pharmacological methods available

that include but are not limited to psycho-social ther-

apies like art (Beard, 2011), music (McDermott et al.,

2012; Wall and Duffy, 2010), and movement ther-

apy (Karkou and Meekums, 2017), cognitive stim-

ulation therapy (Carrion et al., 2018) like memory

training (Woods et al., 2006) or ’Snoezelen’ (Verkaik

et al., 2005), and reminiscence therapy (Gr

¨

asel et al.,

2003; Vernooij-Dassen et al., 2010). These forms of

therapy are in most cases proven to improve qual-

ity of life (Woods et al., 2006) and mood (McDer-

mott et al., 2012; Wall and Duffy, 2010), reduce ag-

gression and levels of agitation, and alleviate feelings

of loneliness (Filan and Llewellyn-Jones, 2006; Wall

and Duffy, 2010) and depression (Verkaik et al., 2005;

Vernooij-Dassen et al., 2010) in elderly with demen-

tia.

This study highlights the application of reminis-

cence therapy (RT) theory in an interactive game. It

is a non-pharmacological approach to slow down the

progress of AD, or ”a structured process of system-

atically reflecting on one’s life”. The main idea be-

hind RT is to help the person with AD to remem-

Mulder, R., Kemper, P., Ottenschot, H. and Hashim, A.

Crafting a Journey into the past with a Tangible Timeline Game: Net Als Toen as a Tool to Enhance Reminiscence in Elderly with Alzheimer’s Disease.

DOI: 10.5220/0012620400003690

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024) - Volume 2, pages 497-504

ISBN: 978-989-758-692-7; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

497

ber parts of their life, for example through stimulating

conversation. This can reduce depression, help with

calming behavior, and is used to treat psychological

symptoms of AD (Lazar et al., 2014). RT can be very

effective since it targets the remote memory of ther-

apy participants (Cotelli et al., 2012). This means that

participant would remember things from their earlier

life but it is harder to remember events from the past

years. This of course does vary per person and even

per day (Cotelli et al., 2012).

To cope with this increasing request for elderly

care and care for people with AD, new and innova-

tive technologies are necessary. Combining technol-

ogy and RT could help support people with AD to en-

hance their memory and aid them in social communi-

cation. For this study, we have developed a prototype

of an interactive tangible game called Net Als Toen

that could assist people with AD and their relatives to

improve their well-being.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Memory and Alzheimer’s Disease

The effect of AD on memory mainly impacts ex-

plicit memory instead of implicit memory (Son et al.,

2002). Explicit memory is the conscious remember-

ing of past events, such as what you ate for breakfast

yesterday. Implicit memory on the other hand is re-

membering past events or manners without intent. An

example could be that someone might unconsciously

remember how to use an old phone with a turning

dial (Treadaway et al., 2019).

Another difference in effect on memory is the dif-

ference between short-term and long-term (remote)

memory. The short-term memory of someone with

AD can be heavily impacted. From someone not

knowing where they put their keys, to not recogniz-

ing their family members. The symptoms can vary

per person and the order and severity of the symptoms

are different for everyone (MacDuffie et al., 2012).

2.2 Reminiscence Therapy

Reminiscence therapy can take many forms (Cotelli

et al., 2012) and can be greatly influenced by the psy-

chologist, researcher, or patient. Methods can be per-

sonalized, like a life story book where personal pho-

tographs or artifacts can be used (Lazar et al., 2014).

There are also more general methods, where the top-

ics are less personal. RT can be divided into two cate-

gories: intrapersonal and interpersonal. Intrapersonal

is a form of individual and cognitive therapy, whereas

interpersonal is done in groups and takes more of

a conversational form (Parsons, 1986). Researchers

also see great opportunities for using multi-media

solutions to spark conversations with other people.

In conclusion, reminiscence therapy can be versatile

and can take many different forms (Subramaniam and

Woods, 2012). Since a social game based on RT is de-

veloped in this project, the focus lies on interpersonal

reminiscence therapy. This means it is important for

the players of the game to start reminiscing together,

to talk about past life events, and to engage in an in-

teractive conversation about these memories.

2.3 Reminiscence and Interactive

Games

Reminiscence therapy has been integrated into inter-

active games in quite some instances already. Pre-

vious work, described in this section, on developing

interactive games for people with AD has shown that

personalization and familiarity are great tools to use

during reminiscence therapy.

Nazareth et al. have created a board game,

”Babbelbord”, to stimulate narrative reminiscence.

Babbelbord has used an interactive and personalized

way to reach this goal. The game is a board game

based on ”Game of the Goose”, which is a gener-

ally well-known game to Dutch elderly people. The

game asks questions from a book called ”Dierbare

herrineringen” on topics like childhood and friend-

ship (Nazareth et al., 2019). Reactions to the game

have been positive overall. It is suggested for future

research to refrain from including sensitive topics so

uncomfortable interactions can be avoided and to for-

mulate questions clearly and in an easy-to-understand

way.

In another study, six different designs for toys

were used for patients with AD. The toys were highly

personalized and adapted to the user. The designers

co-created the products with the families and care-

givers of the patients. Within the design, they used

events and artifacts from the participants’ lives as a

form of reminiscence therapy. Examples are a person-

alized music system and a fidget ring with seashells

for someone who likes going to the beach. Most prod-

ucts had a great result, especially with one patient

who started talking again after a long time of not com-

municating verbally (Treadaway et al., 2019).

Another example of reminiscence therapy is a

study using food stamps in a game for people with

AD. This game was focused on the use of food stamps

and buying food with them. The researchers have

found that this game helped the participants with

memory and calculation (Chang et al., 2013).

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

498

Personalized photos can also be a great tool to use

in reminiscence therapy. One study has used a library

of old photos to spark a conversation between an older

person with AD and a younger person, often a care-

giver or visitor. This has helped initiate a conversation

and therefore start reminiscing (Jiang et al., 2021).

King et al. exposed AD patients to personalized

music and did a small training program. The re-

searchers found that the favored music contributed

to overall less anxiety, agitation, and behavioral is-

sues (King et al., 2018).

2.4 Design Guidelines for People with

AD

The main problems for designing for older people or

Alzheimer’s patients are memory, cognitive, visual,

hearing, and mobility impairments; attention, con-

centration, personality changes; declining language

and speech abilities, decent/no computer and literacy

skills (Ghorbel et al., 2017).

A lot of studies have been done on how to de-

sign for people with AD. There is an abundance of

papers about designing for dementia or Alzheimer’s

patients, all with their categorization of the prob-

lems and the proposed solutions/guidelines (Tread-

away et al., 2019; Astell et al., 2018; Ghorbel et al.,

2017; Satoshi Kawamoto et al., 2014; Carvalho and

Ishitani, 2012; Sunwoo et al., 2010; Orpwood et al.,

2005). There is a lot of overlap in the general rules

and the reasoning behind those rules, so for this

proposal the rules are generalized and put into the

most common categories: cognitive, physical, and so-

cial. The guidelines are based on user experience,

user interface, and system design for dementia or

Alzheimer’s patients.

In a 2018 paper, Astell et al. discuss the main diffi-

culties people with AD can have (Astell et al., 2018).

They have proposed fitting guidelines when design-

ing to accommodate these problems. These guide-

lines present a well-substantiated list of rules to fol-

low when designing for people with AD. This list, as

seen in Table 1, presents the used guidelines.

3 METHODOLOGY

This section explains the design phases of the study.

It consists of three phases: ideation, lo-fi prototyp-

ing, and hi-fi prototyping. During the ideation, brain-

storming was done to develop the initial idea for the

game. Further interviews led to specifying the con-

cept idea. Later, a lo-fi prototype was designed to test

the user experience, which included investigating the

Table 1: This table shows the guidelines from (Astell et al.,

2018) on the left side and the method of implementation on

the right side.

Guidelines Implementation

Choose a goal or task that is

clear, engaging and achievable

Focus on one goal (completing

the timeline), there should al-

ways be a solution

Ensure that instructions are ap-

propriate and understandable

Limited amount of text on an in-

struction slide, use simple rules

Ensure that prompts are effec-

tive and enabling

Focus on what the players can

do instead of what they cannot

do

Avoid timed responses and com-

plex interactions

No time limits or timed interac-

tions

Reduce or eliminate the possi-

bility of failure

There is no way to fail at the

game

Account for inaccurate or im-

precise motor control

Use big pieces that do not re-

quire too precise movements

Create interfaces and interac-

tions that are intuitive and real-

istic

Big buttons that clearly state

what they do

Include visual and auditory ac-

commodations

Use of a screen and an audio

playback option

Tailor the activity to the person’s

interests

Possibility of a personalized

version of the game

Design for an audience (group

activity)

The game can be played with

multiple people

appearance, interaction, and gameplay. The results

from the lo-fi design round led to new design guide-

lines, in addition to the existing guidelines in Table 1,

applied to the hi-fi prototype. During the hi-fi pro-

totype test round, the technology and again the user

experience were evaluated.

Because this study designs a game for people with

AD, it is important to include the target group and

stakeholders in every design phase as much as possi-

ble. By using a user-centered approach, you can con-

tinuously shape your project based on real user inter-

actions and needs (Augusto Wrede et al., 2018). It

makes sure the project remains closely aligned with

the preferences of the target users.

3.1 Design Phases

This section explains the processes involved in this

study.

3.1.1 Ideation

The ideation phase was supported by the extensive lit-

erature review that was carried out beforehand. From

the literature review, a set of guidelines was devel-

oped and followed with the brainstorming session.

During the brainstorming session, the researchers sat

together and used the Aoki method to come up with

Crafting a Journey into the past with a Tangible Timeline Game: Net Als Toen as a Tool to Enhance Reminiscence in Elderly with

Alzheimer’s Disease

499

ideas (Higgins, 1994). From these ideas, the concept

was chosen. In this concept, players are presented

with a physical board, event pieces, an info slot, and a

screen. The players can use the screen to view and ex-

plore information about the events by putting a piece

in the info slot. On the board, the players can move

the event pieces from their starting position on the

bottom to the timeline on the top side of the board.

The board has some LEDs incorporated to indicate if

the piece has been put in the right place. As soon as an

event piece has been put in the right place, the screen

displays conversation starter questions for the players

to talk about. To illustrate the idea, a storyboard was

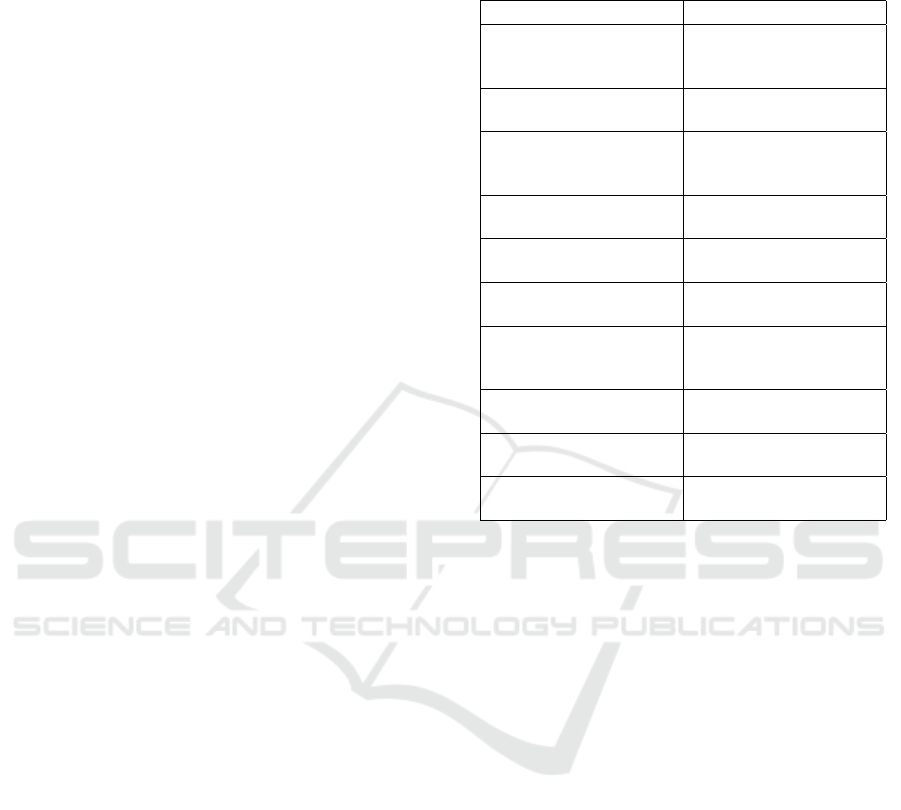

created as in Figure 1.

Figure 1: This storyboard shows seven steps of an example

interaction with the game. 1) Take out a puzzle piece. 2)

Place it on the timeline, the location is correct. 3) Place

another piece on the timeline, the place is almost correct.

4) Place the piece in the info slot. 5) Receive information

about this puzzle piece. 6) Place the piece on another spot in

the timeline, this time the placement is correct. 7) Continue

until the timeline is filled out completely.

To emphasize as much as possible with the tar-

get group, interviews were conducted. Due to ethical

considerations, people with AD were not included in

the interviews. Instead, 5 interviews took place which

consisted of one expert and four caregivers. The ex-

pert interview questions were focused on getting tips

on working with and designing for people with AD,

reminiscence therapy, other forms of therapy, and the

concept of the game. This expert is a senior lecturer

at a university in Malaysia and specializes in psychol-

ogy, aging and dementia studies, and mental health

studies. The caregiver interviews gave insight into

how to take care of someone with AD. Topics of the

interviews included observations of and interactions

with the person with AD, familiarity with technology,

experience with therapy, and the concept of the game.

From the interviews, the participants agreed that

the concept would be interesting to investigate and

expected the game to be an effective and fun conver-

sation starter. The following insights were gathered

from the interviews.

• The game should be intuitive to play. Instructions

should not be difficult to understand. It needs to

be investigated whether having explanations for

specific game elements would be beneficial.

• Personalization should be done via loved ones of

the person with AD, not via nurses. The acqui-

sition of personalized material should be looked

into more clearly.

• The personal events can also include events that

happened during the life of people who are close

to the person with AD.

• The possibility of skipping conversation starter

questions and/or receiving more questions should

be investigated.

• It should be possible to quit the game at any point.

3.1.2 Lo-Fi Prototype

A lo-fi prototype was designed based on the ideas

from the ideation phase and the interview results.

From the interviews, it was concluded that the general

idea for the appearance, interaction with the game,

and ideas for gameplay are worth investigating.

The lo-fi prototype consisted of a physical proto-

type of the timeline board, without any technology in

it yet, accompanied by a touchscreen with a working

User Interface (UI). Figure 2 depicts the outline for

the main slide that users were shown after putting an

event on the info slot. Users were able to travel to sev-

eral information slides from the main one. Figure 3

shows one of the three possible feedback slides (’cor-

rect’, with the other possibilities being ’incorrect’ and

’almost correct’). The example used in the figures

shows one of the general events used in the game.

Figure 2: Main slide with information and buttons.

Figure 3: ’Correct’ feedback slide.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

500

For testing, the technology was mimicked by other

means. For example, the LED lights were indicated

with small pieces of paper in the color of the LED, and

the screen and sound were controlled with a Wizard-

of-Oz method instead of the prototype being auto-

mated. Figure 4 shows the lo-fi testing setup.

Figure 4: Lo-fi testing setup.

The user testing took place at the homes of the

participants. These participants were not part of the

target group for this research, but rather a proxy

group. The participants were family members of the

researchers who were all older than 50 years old. The

user testing process consisted of two phases. The first

phase consisted of four short scenarios which were

done with the participants individually: reading the

instructions, starting the game, evaluating the LED

colors, and evaluating the sounds of the game. Addi-

tionally, the participants were asked what they think

the goal of the game is. For the second phase, the

participants were placed in pairs and they played the

game without instructions from the researchers. The

researchers observed the playtest. Once the partici-

pants completed the game, the researcher interviewed

the participants to evaluate the playtest. The main

goal of the lo-fi tests was to find out if the UI of the

game is intuitive to use, if the instructions are clear

if the sounds and LED colors are used logically, and

if the game can effectively be used as a conversation

starter.

The first phase was tested 6 times, which took ap-

proximately 15 minutes per participant. The second

phase was tested 4 times, which approximately took

45 minutes per test session. Two lo-fi tests were held

with 2 participants playing the game together, while

the other 2 were held with only 1 participant playing.

In these cases, the participant was asked to talk to the

researcher during the game.

Findings from the lo-fi tests were used to improve

the game. Below are some of the main findings that

were gathered during the user test:

• The UI and corresponding LEDs should be im-

proved for various reasons. Many participants

showed difficulties with finding, understanding,

and paying attention to the instructions. Addi-

tionally, some participants showed difficulty un-

derstanding the LEDs.

• The game should include one or multiple per-

sonalization options. Many participants indicated

that personal events would serve a more effective

purpose as conversational starters than a limited

amount of general events.

• The sounds do not have to be fine-tuned. When

played in combination with showing the LED

color, participants clearly understood the mean-

ing of the sounds. More effort should be put into

other aspects of the game due to time limitations.

3.1.3 Hi-Fi Prototype

The goal for the hi-fi prototype was to have a fully

autonomous prototype, which would allow the re-

searchers to test all functionalities of the concept. The

results from the ideation phase and the lo-fi testing led

to the final prototype design of the concept.

The few changes made entail the info slot being

higher and a bit slanted towards the user. The reason

behind these changes was that this design would bet-

ter capture the user’s attention towards the info slot.

In addition to that, the board’s reduced depth was in-

tended to facilitate easier access to the top row of the

slots. Lastly, the board was made to be a bit higher,

to house all the technology in it. Figure 5 shows an

improved version of one of the instruction slides.

Figure 5: One of the instruction slides.

Personalization is one of the elements that was

highly suggested during the lo-fi session. However,

due to time constraints, it was quite challenging to

obtain the materials. Fortunately, it was possible to

create a personalized version of the game with the

help of family members. For the hi-fi test, two types

of personalization were developed. The first one in-

volved incorporating the user’s actual personal events,

while the other version allowed the caregiver to select

from a variety of general events. For this session,

the researchers recruited two types of user groups.

The first group comprised proxy users, aged 50 and

Crafting a Journey into the past with a Tangible Timeline Game: Net Als Toen as a Tool to Enhance Reminiscence in Elderly with

Alzheimer’s Disease

501

above, who happened to be the family members

of the researchers. The second group was the actual

target group, consisting of one person with AD

and their caregiver. Regarding personal events, the

researchers gathered personal information and events

from the proxy users. Only one game was available

as it was created specifically for them. In contrast,

the other version of the game contained 12 general

events, and the caregiver was asked to select 6 events

out of the given options.

The goal of these tests was to find out if the game

could be a tool to initiate conversation between people

with AD and their caregivers, if the users enjoy play-

ing the game and to assess the game’s performance,

both in terms of technical aspects and user interac-

tion.

This session consisted of a playtest and followed

by an interview. During the session, two participants

were present: a person with AD or a proxy user, and

someone close to this person. Due to technical is-

sues, the tests were conducted using the Wizard-of-Oz

method, instead of a fully autonomous prototype.

For both the tests with target users as well as proxy

users, the participants played the game together while

being observed by researchers. After the playtest was

over, both participants joined the interview to answer

questions about their experience. The caregivers were

contacted to get permission to include the person with

AD in the interview. They were also asked to dis-

cuss the game’s content and identify any topics that

should be excluded from both the game and the inter-

view. The Results section includes results from the

hi-fi tests. An impression of the hi-fi playtest setup is

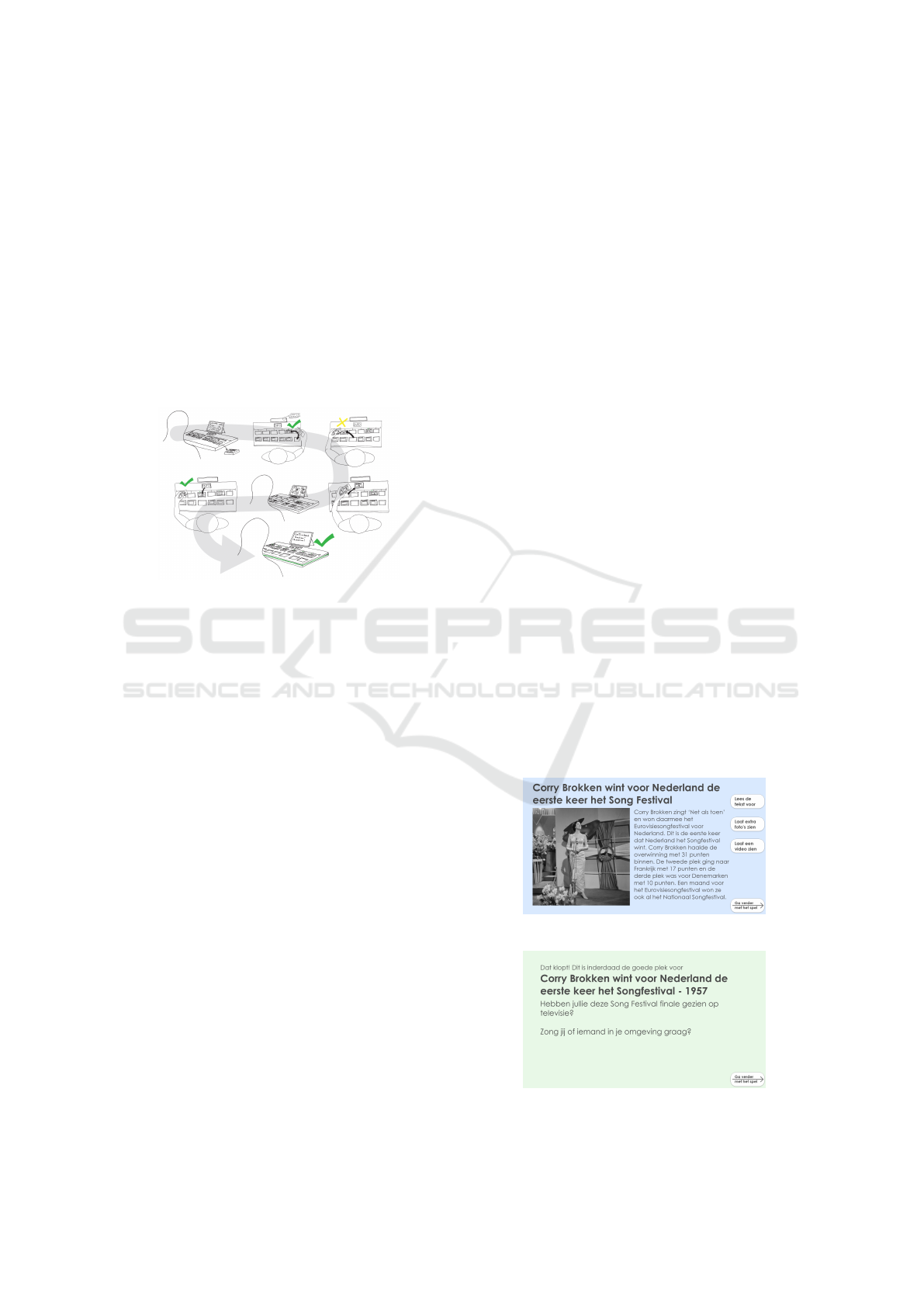

seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Hi-Fi testing setup.

3.2 Ethics

During all stages of this research, informed con-

sent was gathered from the participants. For experts

and proxy users, simple consent for participation and

recording of data was acquired. When dealing with

people within the target group, people with AD, the

consent was also discussed with the caregiver. In all

cases, the person with early-stage AD was able to give

consent.

Transparency has been a crucially important topic

regarding ethics. All participants were aware of the

exact test layout and what was expected of them.

They were told they would be playing a game to-

gether, focusing on creating a timeline of events. The

participants were told the prototype was not function-

ing on its own, so a person puppeteering the game was

sat next to the setup. At the beginning of the test, it

was explained to the participants that they could ask

questions to the observers only if they were unable

to progress using the instructions provided or if any-

thing besides the game was unclear. Next to that, it

was made clear that the researchers would take place

at some distance to observe and take notes.

After the Hi-Fi test, the participants could ask any

last questions or give any comments. They were also

reminded of their right to withdraw from the study at

any time and were thanked for their participation.

The ethical application was approved by the ethi-

cal committee of EEMCS at the University of Twente.

4 RESULTS & DISCUSSION

This section describes the results of the playtests, di-

vided into subsections according to the topics of the

interviews that were held after the playtests.

4.1 Results

In total, four playtests were carried out with partici-

pant pairs. Two pairs consisted of one person from

the target group and one caregiver, while the other two

served as proxy pairs.

When observing the participants it became clear

that none of the participants completed the instruc-

tions before trying out the game. As a result of

this, the conversation starter questions were often not

seen or quickly disregarded. Additionally, this caused

some groups to be left without understanding what the

info slot was meant for, resulting in the info slot not

being used as often as anticipated. Despite this, all

pairs were able to play the game and talk about their

past and/or the presented general events.

Three out of four pairs were enthusiastic about the

game. Their feedback included, among other things,

that the puzzling aspect was a positive feature. The

fourth pair noted they were not interested in the topics

of the general events, which had a negative effect on

their enjoyment.

All pairs were able to interact with the game with-

out help until completion and noted that the lights and

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

502

sounds used gave clear feedback about the status of a

placed piece. However, the visual feedback on the

screen was often not noticed or quickly disregarded.

Pairs who had not read the instructions during the

game were led through them afterward. Participants

mentioned the instructions were not too complex and

did not contain too much information. However, fu-

ture versions of the game would need a better way to

keep the attention of users.

The duration of the game was highly dependent

on how much the participants talked with each other.

Those who did not talk a lot noted that the game

seemed brief. Most participants found the replayabil-

ity of the game high, with the side note that the event

pieces would need to be different. One pair noted that

the number of pieces could be overwhelming, but oth-

ers found 6 to be a suitable number of pieces.

The participant pairs with one person from the tar-

get group played the game with general event pieces.

Beforehand, a poule of 12 event pieces was prepared

by the researchers. Together with the caregiver, 6 out

of these 12 event pieces were chosen before the start

of the playtest based on the assumed preferences of

the participant from the target group. Some events

were found to be more enjoyable than others, depend-

ing on whether the participants knew much about the

event. It was also mentioned that the music events

were too modern. One participant pair noted they

would have liked to play the game with event pieces

from their personal life.

Proxy users played the game with personalized

event pieces. Both pairs were enthusiastic about the

events and the game in general. Even though the

events were familiar to the players, it did not take

away the puzzling aspect. There were mixed opinions

about the difficulty of the game, with one pair sug-

gesting options to make the game easier and the other

to make the game more difficult. It was also noted that

it is not possible to control which memories, good or

bad, an event piece can bring up. This should be kept

in mind when picking event pieces, and it is good to

have someone present when playing the game who

can comfort the users.

4.2 Limitations

Limitations related to testing and project setup should

be taken into consideration. In general, the number of

people who participated in interviews and user test-

ing was low and did not include many people from

the target group. It should also be considered that all

participants were Dutch, leaving no room for investi-

gating cultural differences. User testing was also done

with self-made lists of questions instead of scientifi-

cally grounded existing questionnaires. Additionally,

due to unforeseen technical issues, the final prototype

did not function autonomously and it was not possible

to play audio and video directly.

4.3 Conclusion

Net Als Toen was able to provide an enjoyable experi-

ence for most participants of the study. The personal-

ized version of the game, which includes events from

the users’ personal lives, proves to be a highly effec-

tive conversation starter. However, it is important to

note that this study was conducted with a small group

of people. Although lo-fi user tests were performed,

any future prototype will require more usability test-

ing. Most guidelines from Table 1 are met during the

hi-fi tests, except the unclear instructions. Thus, im-

portant aspects, such as users omitting the instruction

slides or not utilizing the info slot, should be thor-

oughly considered before future user tests. An es-

tablished questionnaire should be used to gather user

feedback.

In conclusion, our prototype requires further test-

ing. Future testing should include a fully working

prototype, subjected to a more extensive, broader, and

more diverse participant pool, particularly including

individuals with AD. The integration of personalized

events is recommended to enhance enjoyment and en-

courage the participants to share their memories.

REFERENCES

Anand, P. and Singh, B. (2013). A review on cholinesterase

inhibitors for alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Phar-

macal Research, 36(4):375–399.

Astell, A. J., Czarnuch, S., and Dove, E. (2018). System de-

velopment guidelines from a review of motion-based

technology for people with dementia or mci. Frontiers

in Psychiatry, 9:3–7.

Augusto Wrede, J., Kramer, D., Alegre, U., Covaci, A., and

Santokhee, A. (2018). The user-centred intelligent

environments development process as a guide to co-

create smart technology for people with special needs.

Universal Access in the Information Society, 17:117.

Balouch, S., Rifaat, E., Chen, H. L., and Tabet, N.

(2019). Social networks and loneliness in people with

alzheimer’s dementia. International Journal of Geri-

atric Psychiatry, 34(5):666–673.

Beard, R. L. (2011). Art therapies and dementia care: A

systematic review. Dementia, 11(5):633–656.

Carrion, C., Folkvord, F., Anastasiadou, D., and Aymerich,

M. (2018). Cognitive therapy for dementia patients: A

systematic review. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive

Disorders, 46(1-2):1–26.

Crafting a Journey into the past with a Tangible Timeline Game: Net Als Toen as a Tool to Enhance Reminiscence in Elderly with

Alzheimer’s Disease

503

Carvalho, R. and Ishitani, L. (2012). Motivational fac-

tors for mobile serious games for elderly users.

Simp

´

osio Brasileiro de Games e Entretenimento Digi-

tal (SBGames), pages 26,27.

Chang, K., An, N., Qi, J., Li, R., Levkoff, S., Chen, H., and

Li, P. (2013). Food stamps: A reminiscence therapy

tablet game for chinese seniors. 2013 ICME Interna-

tional Conference on Complex Medical Engineering.

Cotelli, M., Manenti, R., and Zanetti, O. (2012). Remi-

niscence therapy in dementia: A review. Maturitas,

72(3):203–205.

Filan, S. L. and Llewellyn-Jones, R. H. (2006). Animal-

assisted therapy for dementia: A review of the litera-

ture. International Psychogeriatrics, 18(4):597–611.

Ghorbel, F., M

´

etais, E., Ellouze, N., Hamdi, F., and Gar-

gouri, F. (2017). Towards accessibility guidelines of

interaction and user interface design for alzheimer’s

disease patients. In Advances in Computer-Human In-

teractions(ACHI) 2017.

Gr

¨

asel, E., Wiltfang, J., and Kornhuber, J. (2003). Non-drug

therapies for dementia: An overview of the current sit-

uation with regard to proof of effectiveness. Dementia

and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 15(3):115–125.

Higgins, J. M. (1994). 101 creative problem solving tech-

niques : the handbook of new ideas for business. New

Management Pub. Co.

Jiang, L., Siriaraya, P., Choi, D., and Kuwahara, N. (2021).

A library of old photos supporting conversation of two

generations serving reminiscence therapy. Frontiers in

Psychology, 12:10.

Kaduszkiewicz, H., Zimmermann, T., Beck-Bornholdt, H.-

P., and van den Bussche, H. (2005). Cholinesterase

inhibitors for patients with alzheimer’s disease: Sys-

tematic review of randomised clinical trials. BMJ,

331(7512):321–327.

Karkou, V. and Meekums, B. (2017). Dance movement

therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database of System-

atic Reviews, 2017(2):3,4.

King, J., Jones, K., Goldberg, E., Rollins, M., MacNamee,

K., Moffit, C., Naidu, S., Ferguson, M., Garcia-

Leavitt, E., Amaro, J., and et al. (2018). Increased

functional connectivity after listening to favored mu-

sic in adults with alzheimer dementia. The Journal Of

Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, 6(1):1–7.

Lazar, A., Thompson, H., and Demiris, G. (2014). A

systematic review of the use of technology for rem-

iniscence therapy. Health Education & Behavior,

41(1):51S, 52S.

MacDuffie, K. E., Atkins, A. S., Flegal, K. E., Clark,

C. M., and Reuter-Lorenz, P. A. (2012). Memory dis-

tortion in alzheimer’s disease: Deficient monitoring

of short- and long-term memory. Neuropsychology,

26(4):509–516.

McDermott, O., Crellin, N., Ridder, H. M., and Orrell,

M. (2012). Music therapy in dementia: A narrative

synthesis systematic review. International Journal of

Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(8):781–794.

Nazareth, D. S., Burghardt, C., Capra, A., Cristoforetti, P.,

Lam, W., van Waterschoot, J. B., Westerhof, G. J.,

and Truong, K. P. (2019). Babbelbord: A personal-

ized conversational game for people with dementia.

Communications in Computer and Information Sci-

ence, page 169–173.

Nichols, E., Steinmetz, J. D., Vollset, S. E., Fukutaki, K.,

Chalek, J., Abd-Allah, F., Abdoli, A., Abualhasan, A.,

Abu-Gharbieh, E., Akram, T. T., and et al. (2022). Es-

timation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019

and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the

global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet Pub-

lic Health, 7(2):e106.

Orpwood, R., Gibbs, C., Adlam, T., Faulkner, R., and

Meegahawatte, D. (2005). The design of smart

homes for people with dementia—user-interface as-

pects. Universal Access in the Information Society,

4(2):156–164.

Parsons, C. L. (1986). Group reminiscence therapy and lev-

els of depression in the elderly. The Nurse Practi-

tioner, 11(3):75,76.

Satoshi Kawamoto, A. L., Martins, V. F., and Soares Cor-

rea da Silva, F. (2014). Converging natural user in-

terfaces guidelines and the design of applications for

older adults. 2014 IEEE International Conference on

Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC).

Son, G.-R., Therrien, B., and Whall, A. (2002). Implicit

memory and familiarity among elders with dementia.

Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 34(3):263–267.

Subramaniam, P. and Woods, B. (2012). The impact of indi-

vidual reminiscence therapy for people with dementia:

Systematic review. Expert Review of Neurotherapeu-

tics, 12(5):545–555.

Sunwoo, J., Yuen, W., Lutteroth, C., and W

¨

unsche, B.

(2010). Mobile games for elderly healthcare. Pro-

ceedings of the 11th International Conference of the

NZ Chapter of the ACM Special Interest Group on

Human-Computer Interaction on ZZZ - CHINZ ’10.

Treadaway, C., Fennell, J., Taylor, A., and Kenning, G.

(2019). Designing for playfulness through compas-

sion: Design for advanced dementia. Design for

Health, 3(1):27–47.

Verkaik, R., van Weert, J. C., and Francke, A. L. (2005).

The effects of psychosocial methods on depressed, ag-

gressive and apathetic behaviors of people with de-

mentia: A systematic review. International Journal of

Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(4):301–314.

Vernooij-Dassen, M., Vasse, E., Zuidema, S., Cohen-

Mansfield, J., and Moyle, W. (2010). Psychosocial

interventions for dementia patients in long-term care.

International Psychogeriatrics, 22(7):1121–1128.

Wall, M. and Duffy, A. (2010). The effects of music ther-

apy for older people with dementia. British Journal of

Nursing, 19(2):108–113.

Wimo, A., Ali, G.-C., Guerchet, M., Prince, M., Prina, M.,

and Wu, Y.-T. (2015). Adi - world alzheimer report

2015.

Woods, B., Thorgrimsen, L., Spector, A., Royan, L., and

Orrell, M. (2006). Improved quality of life and cogni-

tive stimulation therapy in dementia. Aging & Mental

Health, 10(3):219–226.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

504