Spread the Word! BaLex, A Gamified Lexical Database for Collaborative

Vocabulary Learning

Enzo Simonnet

1,2 a

, Mathieu Loiseau

1 b

,

´

Emilie Magnat

3 c

and

´

Elise Lavou

´

e

1,2 d

1

Universit

´

e Jean Moulin Lyon 3, Iaelyon School of Management, Lyon, France

2

Univ. Lyon, INSA Lyon, CNRS, UCBL, LIRIS, UMR5205, F-69621, Villeurbanne, France

3

Universit

´

e Lyon 2, Laboratoire ICAR UMR 5191, France

Keywords:

Vocabulary Learning, Gamification, Motivation, Collaboration, Lexical Database.

Abstract:

Many tools have shown positive effects on vocabulary learning. They can enable learners to work au-

tonomously, both inside and outside the classroom. However, learning the few thousand words needed to

master a language takes time, and maintaining learners’ motivation over long periods is a key issue. More-

over, Technology-Assisted Vocabulary Learning (TAVL) tools rarely offer features to involve teachers in the

learners’ vocabulary learning process, although this type of guidance has been shown to be effective. In this

context, we propose a gamified lexical database for collaborative learning named BaLex, designed according

to an iterative design process, intended to (1) improve vocabulary learning, (2) keep learners motivated over the

long term (months and years of learning), (3) support collaboration between learners, and (4) involve teachers

in the learning process carried out autonomously. Learners have access to individual and group lexicons with

learning features, collaborative features and gamified indicators, the latter thought to enhance learners’ moti-

vation and provide feedback. We conclude by discussing the possibilities offered by the generic architecture

of BaLex and the applications that can be added to enrich vocabulary learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Vocabulary learning is an essential dimension of for-

eign language learning, like grammar, phonology

or culture (Nation, 1999). However, it is rarely

addressed explicitly, neither in the classroom nor

through out of class activities (Oxford and Crookall,

1990). In French higher education for instance, lan-

guage classes for non specialists are typically granted

around 20 hours each semester. In this context, the

mastery of the necessary few thousands words

1

has

to be acquired in a large part autonomously, out-

side the classroom, while classroom time is dedicated

to interaction and production tasks (Freund, 2016).

Many studies highlight the need to foster independent

and autonomous learning (Ginanjar Anjaniputra and

Salsabila, 2018; Farangi et al., 2015).

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9740-5212

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9908-0770

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8857-9405

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2659-6231

1

Some 3000 families of words, at least, are required to

communicate in a foreign language (Laufer, 1992).

Numerous Technology-Assisted Vocabulary

Learning (TAVL) tools

2

have been developed and

have shown positive impact on learning processes,

particularly for acquiring and practicing new vocabu-

lary (Hao et al., 2021). However, these tools have also

shown certain limitations when used autonomously

by learners. Based on a review study on TAVL,

(Klimova, 2021) suggested such applications should

be used in a guided and controlled context to lead to

an effective learning process. Therefore, implicating

the teacher in the learning process appears as a key

element to ensure that students learn vocabulary

efficiently. Furthermore, vocabulary learning is a

complex, multi-skilled task (Tremblay and Anctil,

2020) that can prove taxing for learners, and thus

likely to demotivate them (Tseng and Schmitt, 2008).

Maintaining motivation over long periods of time is

2

Although the acronym TAVL is still not widely

used, we believe it makes a logical addition to Mobile-

Assisted Vocabulary Learning (MAVL) (Ye et al., 2023; Ma,

2017) and Computer-Assisted Vocabulary Learning (CAVL)

(A. Al-Jasir, 2019). It is noteworthy that the expression

”Technology-Assisted Vocabulary Learning” has already

been used in (Hao et al., 2021).

388

Simonnet, E., Loiseau, M., Magnat, É. and Lavoué, É.

Spread the Word! BaLex, A Gamified Lexical Database for Collaborative Vocabulary Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0012620800003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 388-395

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

a key component in vocabulary learning and can be

supported by TAVL.

In this context, we propose BaLex, a personal-

ized digital vocabulary learning environment ensuring

continuity outside the classroom. Its features were de-

signed using an iterative and participatory design pro-

cess. We first conducted a survey to identify teach-

ers’ and students’ expectations regarding such a tool.

Based on the results of this study, and on a theoretical

background on vocabulary learning, BaLex has been

developed as a gamified vocabulary notebook that en-

courages collaboration between students. Learners

are provided with both individual and group lexicons,

as well as outside resources. Teachers can also inter-

act with the learners and share lists of words with their

groups of students.

In this paper, we first delve into the theoreti-

cal background on vocabulary learning and identify

the specific challenges that arise, particularly when

it comes to learner motivation. We also review ex-

isting TAVL tools to identify the relevant functional-

ities they propose, but also limitations in the field.

We then present the results of our preliminary study

conducted with language teachers and students. Fi-

nally, we present the features and the architecture of

the BaLex software. In conclusion, we outline the re-

search avenues offered by such a vocabulary learning

environment and present the upcoming improvements

that will complete the lexical database BaLex.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Learning and teaching vocabulary constitutes a part of

any foreign language studying program. Therefore, it

is important to place vocabulary in proper perspec-

tive. Nation’s “four strands” (Nation, 2013, pp.2–3)

offer a comprehensive model for characterizing lan-

guage learning activities. According to Nation, each

strand should receive the same attention. The first two

strands are meaning-focused: (1.) “comprehensible

meaning-focused input” (2.) “meaning-focused out-

put”. In both strands, the focus of the learner is cen-

tered on the information conveyed to/by them. The

third strand concerns activities focusing on form, or

accuracy. In the context of vocabulary learning, this

strand implies that “a course should involve the di-

rect teaching of vocabulary and the direct learning and

study of vocabulary” (Nation, 2013, p. 2). The last

strand (4.) is fluency development i.e. the learners

become more fluent with what they already know.

In this perspective, vocabulary learning, present in

all four strands, plays a fundamental role in the lan-

guage learning process. Studies indicate that profi-

ciency in vocabulary plays a crucial role for second

language readers, and the lack thereof constitutes the

most significant challenge for Second language (L2)

readers to surmount (Alqahtani, 2015).

Mastering vocabulary requires the synthesis of

many different cognitive elements (Tremblay and An-

ctil, 2020). Tremblay et al. (2016) propose to charac-

terize lexical competence through three components:

knowledge, skills and attitudes. They refer to at-

titudes towards vocabulary as ”lexical sensitivity”.

Among many examples of such manifestations pro-

posed in their work, we can highlight the following:

(1.) be enthusiastic about learning new words and

phrases; (2.) be motivated to learn new words; (3.)

enjoy sharing their lexical discoveries with others;

(4.) show an interest in learning the meaning of a

new word encountered in a text and understanding its

subtleties.

This underlines the importance of motivation in

vocabulary learning, and maintaining learners’ moti-

vation over a long period emerges as a key feature

(Tseng and Schmitt, 2008). The notion of “lexical

sensitivity” also involves teachers and is echoed by

Manzo and Sherk (1971) who highlight that teachers

communicating excitement about word learning and

the ideas being developed facilitate vocabulary learn-

ing. Therefore, another essential element in enhanc-

ing student vocabulary learning includes the teacher’s

attitude on said learning (Rausch, 1969).

Digital learning environments offer tools and solu-

tions to equip teachers and learners for the challenges

of vocabulary learning. We review in next section the

potential of such resources to foster learners’ auton-

omy and motivation for vocabulary learning. Existing

studies indicate that the computer-assisted setting has

the potential to enhance students’ linguistic aware-

ness, facilitate peer interaction and collaboration, and

promote learner autonomy within a learner-centered

learning environment (Benson, 2013, p. 146).

3 TECHNOLOGY ASSISTED

LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

Many TAVL tools have been developed over the past

two decades. Yu and Trainin (2022) analysed 34 stud-

ies with 2,511 participants yielding 49 separate effect

sizes and identified a moderate overall positive effect

size for using technology to learn L2 vocabulary. On a

similar scope, Hao et al. (2021) made a meta-analysis

of 45 studies conducted between 2012 and 2018 on

TAVL for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learn-

ers and found an overall large positive effect of TAVL,

compared to traditional instructional methods. Fi-

Spread the Word! BaLex, A Gamified Lexical Database for Collaborative Vocabulary Learning

389

nally, Lin and Lin (2019) conducted a meta-analysis

examining more particularly the effectiveness of L2

Mobile-Assisted Vocabulary Learning (MAVL) in 33

studies carried out between 2005 and 2018, and found

a positive and large effect size on L2 word retention.

These 3 meta-reviews all agree on the positive effect

of TAVL for vocabulary learning and point out that

these tools need to support learners’ motivation and

guide them through the learning process.

Games and gameful tools are widely used for vo-

cabulary learning. They can take various forms, such

as role playing games like RPG Story (Hwang and

Wang, 2016), virtual reality games like House of Lan-

guages (Alfadil, 2020) or gamified tools like Idiom-

sTube (Lin, 2022). Various game elements (virtual

money, points, badges, trophies) are used to reward

learners’ actions that benefit their learning. The im-

pact of games and gamification are studied in several

literature reviews on TAVL (Wang et al., 2021; Lin and

Lin, 2019; Zou et al., 2021) as approaches to increase

learners’ motivation and vocabulary knowledge.

Another way to enhance learning in vocabulary

tasks is to offer collaboration opportunities (Trim,

2002). Zou et al. (2021) showed in their review that

collaborative vocabulary learning embedded in game

environments could tend to produce effective learn-

ing outcomes. For instance, Quizlet (Bueno-Alastuey

and Nemeth, 2020) and Linguatorium (Chukharev-

Hudilainen and Klepikova, 2016) offer the possibil-

ity to share vocabulary lists with other users and both

were successfully used in a way that improved vo-

cabulary learning among learners. However, we ob-

serve that few collaborative functionalities are inte-

grated into existing TAVL(Wang et al., 2021; Lin and

Lin, 2019).

Finally, we observe that only few tools specifically

address the concern of including the teacher in the

learning process, thus limiting their ability to guide

learners and ensure that they learn vocabulary effi-

ciently outside the classroom. One rare example of

such inclusion can be found in Moodle in which learn-

ers and teachers can communicate directly via chat

messaging while implementing a vocabulary learn-

ing activity (Barcomb and Cardoso, 2020). Other

examples include Vocabulary.com (Nishioka, 2020),

which enables learners’ progress to be tracked, and

IdiomsTube (Lin, 2022), which provides an interface

for teachers to automatically compile reports on the

learning progress of students and classes.

4 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

In summary, previous studies on the field of TAVL

highlighted the effectiveness of technology-assisted

approaches in enhancing vocabulary learning for sec-

ond language (L2) learners, most often in the con-

text of EFL. The studies identified various types of

digital tools used for vocabulary learning, emphasiz-

ing their impact on vocabulary retention, motivation,

attitudes, and perceptions. Additionally, they high-

lighted several key factors influencing the effective-

ness of TAVL, such as learner motivation and enjoy-

ment, and teacher involvement in the process of using

the tool to guide learners outside the classroom (Teng,

2014). Based on these findings, and to address gaps in

existing research, we identified three research objec-

tives to guide the development of the BaLex lexical

database:

1. Improving vocabulary learning and keeping learn-

ers motivated on the long term;

2. Supporting collaboration between learners;

3. Involving teachers in the learning process, to

guide the learning task carried out in autonomy.

5 PRELIMINARY STUDY ON

TEACHERS’ AND STUDENTS’

PRACTICES AND

EXPECTATIONS

5.1 Methodology and Participants

We conducted a preliminary study on lexicon learning

practices in the context of language classes for non-

specialists. This study involved two separate ques-

tionnaires — one for learners and one for teachers —,

followed by semi-structured interviews with teachers.

It was mainly carried out at the University Lyon 2.

The aim was to confront the literature with field data:

actual practices and in a user-driven approach, con-

crete needs and associated features.

The teacher questionnaire gathered 70 complete

responses. After regular demographic questions, we

asked them about 3 main themes: 1) importance

granted to, and class time spent on vocabulary teach-

ing; 2) useful features for vocabulary learning tools,

both for them and their students; 3) means to motivate

students when using the tools. The semi-structured

interviews were conducted to allow the teachers to ex-

plain more thoroughly their practice and expectations.

The learner questionnaire gathered 124 complete an-

swers. After demographic questions, we asked them

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

390

about the features they would like in a vocabulary

learning tool that would be linked to the language

course.

5.2 Results

5.2.1 Vocabulary Teaching Practices and

Teachers’ Expectations

The survey brought insights into vocabulary teach-

ing practices and teachers’ perceptions on the subject.

To the question ”How important do you think lexi-

cal skills are in language learning?”, on a 5 degrees

Likert scale, the mean result was 4.4, showing the im-

portance of vocabulary learning for teachers. They

declared spending on average 11 hours (with a me-

dian of 6 hours) every semester on explicit vocabulary

learning with a class. Most of them were enthusiastic

about having tools allowing autonomous vocabulary

learning on the students’ part.

5.2.2 Students’ Motivation for Vocabulary

Learning Tools

In exploring the motivations behind learners using

new vocabulary learning tools, our focus was on iden-

tifying the factors influencing their choice. By an-

alyzing teachers’ responses to the questionnaire, we

uncovered two aspects: the ”game” aspect, empha-

sizing pleasure and entertainment, and the “serious”

aspect, highlighting the learning facet hidden within

the activities.

Games and playing emerged as key elements

bringing pleasure to learners. Terms such as ”fun”

(”learning different from classes is fun”), ”attrac-

tiveness,” ”gadget” (a new and amusing object), and

”playful” are recurrent, emphasizing the enjoyment

derived from games. Some teachers linked games to

digital technologies and attributed the playful effect

to the digital support itself. They encouraged making

these tools accessible on mobile phones and tablets,

allowing for autonomous learning outside the class-

room. Conditions for creating a playful atmosphere

include usability (ease of use), affordances, and inter-

face attractiveness. Moreover, the possibility of re-

mote group play was identified as a way to foster in-

teraction, socialization, and the formation of friend-

ships among learners.

Regarding the didactic aspect, teachers enumer-

ated characteristics essential for achieving learning

objectives. Feedback, either in the form of grades,

bonus points, or visualizing learners’ progress, was

deemed crucial. Visualizing learning steps was em-

phasized, with teachers proposing graphic representa-

tions to make progress and learning evolution visible.

Multiple requirements for lexicons were also consid-

ered essential: customizable, adapted to learners’ lev-

els, contextualized, anchored in learning situations.

The ideal scenario is inline with Nation’s strands and

involves production task for learners to create utter-

ances involving newly learned words. Teachers ad-

vocated for vocabulary to be linked to the course,

allowing learners and teachers to create their own

word lists. To ensure regular tool use, some teachers

proposed introducing these tools in class, integrating

them into assignments, and dedicating time to these

activities during lessons.

5.2.3 TAVL Features

The option of sharing a common vocabulary across

the entire class was the most demanded feature (31%

of teacher respondents). Teachers expressed a de-

sire to share word lists with their students. Follow-

ing closely, 26% of instructors voted for feedback,

acknowledging its crucial role in the learning pro-

cess. The possibility of having a personal vocabu-

lary notebook reached 24%, while direct messaging

received the lowest percentage at 17%. It is notewor-

thy that in the ”other” category, teachers proposed ad-

ditional features such as creating a collaborative and

exportable glossary — which not unlike the shared

common vocabulary — and access digital resources

like corpora and selected usage examples.

On the students’ side, we found a similar interest

for the vocabulary notebook as 74% of the students

found it useful in a vocabulary learning tool. Among

the other most required features, the ability to moni-

tor their own progression was highlighted by 92% of

them and a feature for exchanging with other learners

reached 62%.

6 BaLex

This preliminary study was the first step of the de-

sign and development of a collaborative vocabulary

learning tool using a user-centered approach (Nor-

man, 2013; Bastien and Scapin, 2004). After the anal-

ysis of the results of the preliminary study, we con-

ducted a meeting with several teachers during which

a functioning prototype was presented to them. This

allowed us to gather remarks and suggestions in order

to adapt the tool to their pedagogical practices.

Spread the Word! BaLex, A Gamified Lexical Database for Collaborative Vocabulary Learning

391

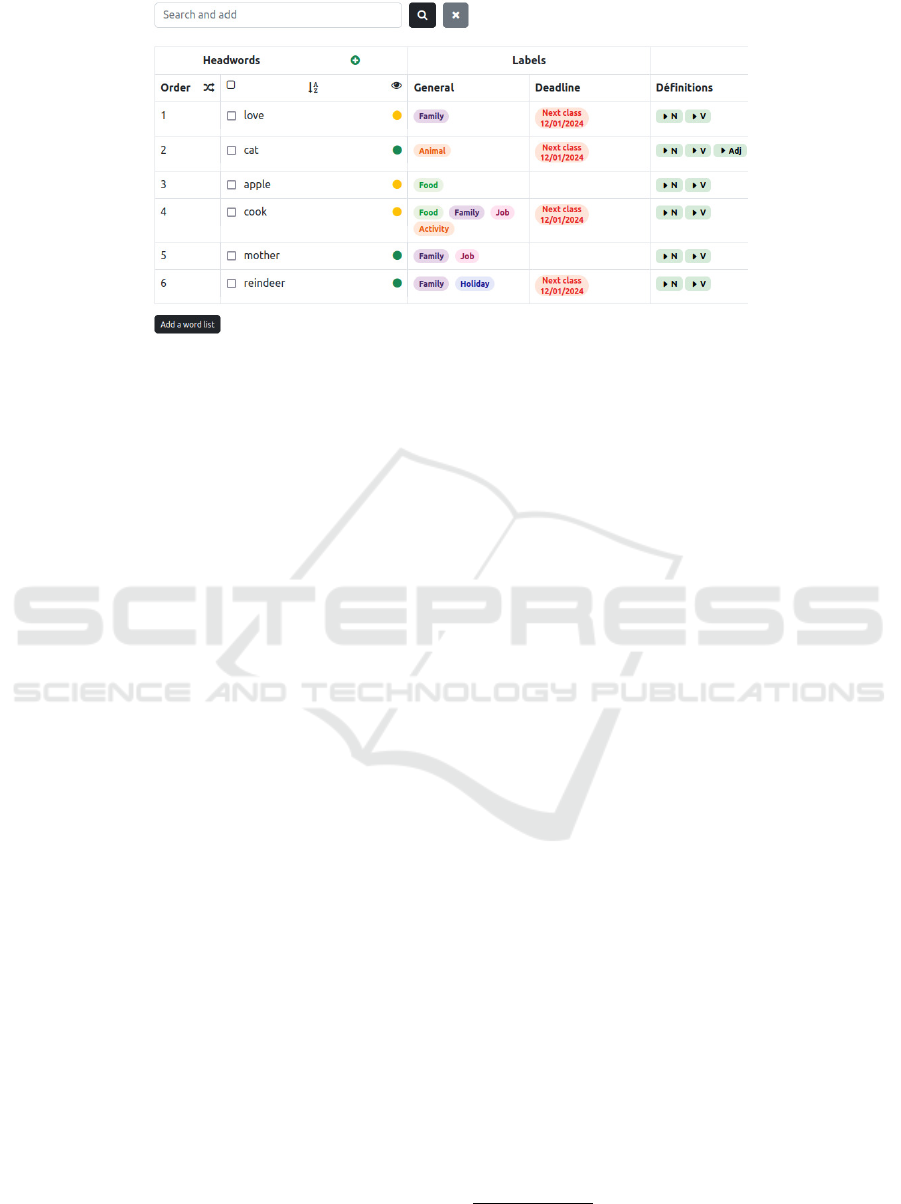

Figure 1: An example of shared lexicon. At the top, the bar allows users to search for words inside the lexicon and, if not

found, in the Wiktionary. Words can be sorted by addition date (order), alphabetically, randomly, by label or by deadline.

Toggle buttons allow quick display of definitions without having to change pages. The button at bottom left allows users to

add word lists (batch mode).

6.1 Main Features

6.1.1 Individual and Group Lexicons

Learners have access to various vocabulary note-

books, which we refer to as a ”lexicons”. BaLex de-

fines three distinct levels for organizing lexical data.

The primary lexical database encompasses reliable in-

formation extracted from the Wiktionary in the tar-

get language. Second, at the group level collections

are dynamically managed by a student group (e.g. a

whole class or just a work group), with or without a

supervising teacher. To share a collaborative lexicon

with other learners, anyone can create a group and

invite new members into the group. The group will

automatically have a lexicon available to all its mem-

bers. The collaborative lexicons each contain a dis-

cussion zone enabling members to interact and each

entry page provides a “comment” feature. Both fea-

tures are meant to encourage discussion. Finally, each

user has their own personal lexicon.

The features on the lexicon’s main page (see Fig.

1) allow teachers and learners to sort, organize and

manipulate large lexicons, displayed as lists of words.

Users can sort the words (by alphabetical order, order

of added date, or random order), have a quick view of

the words definition, select some words and perform

specific actions on the selection. They can export a se-

lection of words into a different lexicon, delete them,

mark them as known or unknown, and apply labels

and deadlines.

Labels enable users to list headwords according to

various criteria, in the form of tags attached to a word

and providing information about it (e.g. the labels An-

imal, Travel, Feeling, etc.). Labels thus serve both

an organizational and a learning purpose. Indeed, in

order to create their own labels and apply them to

words, learners need knowledge about the meanings

of the words they are labelling. Therefore, they might

gain some understanding of the concept of polysemia.

Labels consist of several parameters: a name, a type

(general or milestone), a category of users that can

access it (personal, group or public).

The general labels are added by users, they can

have a ”universal” scope (e.g., Sport, Animal), a

scope specific to the label’s creator (e.g., Summer

2020, Words that sound good) or a scope specific

to a group (e.g., Words we laughed about). The

deadlines operate similarly to general labels, but they

also require a date (e.g. Next class, 05/01/2024

or Final exam, 20/03/2024). When the date is

reached, a dialog prompts the label creator whether to

delete or renew the milestone (in which case, a new

date is requested).

The owner parameter determines the label access

rights. There are 3 modes: Personal Labels belong to

a unique user who has exclusive access to it (i.e. view,

modify, use

3

, delete). Group Labels are accessible to

a unique group and only group members can access

them. This type of labels can allow teachers to mark

some words with useful and contextual information

for the students, with labels such as “False friend” or

“For the project”. Public Labels are available to all

BaLex users and everyone has access to them. For

critical actions, such as deleting or renaming the la-

bel, an ”approval” vote is required before making the

change. Every BaLex user can participate and vote

3

By “use” we mean applying the label to an entry or

removing it from an entry.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

392

”In favour” or ”Against” the action.

On the lexicon main page, users can look up words

in the search bar. It searches if the word is already in

the lexicon, if not it proposes to add it. Batch addition

of a list of words is also available to users, especially

teachers who might want to share a list of objectives

in one single step. For every word in the list, the soft-

ware looks up an existing entry and, if needed, im-

ports lexical information. The lexical information is

extracted from the Wiktionary and a copy is stored in

the application database using Python scripts that au-

tomatically retrieve and structure it. Each language

has its own Wiktionary with its own structure and

templates (we currently process the French and En-

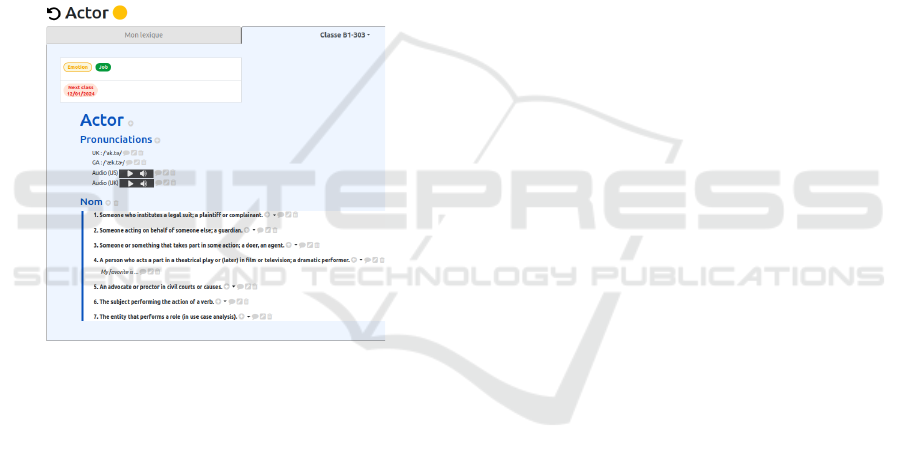

glish wiktionaries). Users can then consult the entry

and modify all the information: add, remove and re-

order pronunciations, parts of speeches, definitions,

examples, sub-definitions and sub-examples.

Figure 2: An example of entry. In the top left, the arrow

takes the user back to the lexicon. Learners can click on

the orange dot to turn it green, indicating that they know

the word. Labels are displayed above pronunciations, then

parts of speech with their definitions and examples. Each

element can be modified, commented, deleted or created.

6.1.2 Gamified Indicators

As discussed in section 3, keeping learners motivated

is one of the main challenges for vocabulary learning

and encouraging learners to collaborate is one way to

motivate them. Another approach consists in gam-

ifying the learning process, which can also provide

feedback to learners on their activities and progress

(Lavou

´

e et al., 2019). According to Deterding, ”gam-

ification is an informal umbrella term for the use of

video game elements in non-gaming systems to im-

prove user experience (UX) and user engagement”

(Deterding et al., 2011). Examples of game elements

include completing quests or earning rewards, scores,

badges, trophies (Dumas Reyssier et al., 2023).

We relied on the methodology proposed by Halli-

fax et al. (2018) to design and implement game ele-

ments in BaLex. We first listed the activities available

in BaLex and then identified the users’ expected be-

havior in particular regarding vocabulary learning and

collaboration. Finally, we selected the game elements

best suited to these behaviors. This process aims to

create game elements that, in addition to being mo-

tivating, guide learners by giving them positive feed-

back and showing them a methodology for learning

vocabulary.

We propose 8 different types of badges, a daily

quest and a point system that applies to all game ele-

ments. The daily quest requires to complete 3 tasks:

adding a word to one of their lexicons, modifying the

information on an entry and applying a label to an

entry. Once they complete the 3 tasks in a 24 hours

span, they complete the quest and are rewarded 10

points. This element is meant to encourage regularity

and daily training.

The 8 types of badges are the following: Vocabu-

lord rewards the number of words added by learners

in all their lexicons. It relates to vocabulary width

(number of known words) as it encourages learners

to add new words; Labellicist rewards the number of

labels applied by learners. This badge is related to

vocabulary depth (meaning, polysemy): learners have

to understand the meaning(s) of a word in order to la-

bel it; Knowledge Guardian rewards the number of

views on all learners’ entries pages. It is also related

to vocabulary depth as it encourages learners to con-

sult frequently the lexical information; Time Mas-

ter rewards the number of consecutive days learners

completed the daily quest. It encourages learners to

memorize words by emphasizing regularity and rep-

etition. Altruist rewards the number of headwords

added to a public label by learners. Steps: [1, 5, 10,

20, 35]. With the use of public labels, this badge in-

cites learner collaboration on shared lexicons, and tar-

gets word depth (like the labellicist). Acolyte Anony-

mous rewards the number of entries modified by

learners in a group lexicon. This badge encourages

learners to collaborate to enrich the group’s lexicon.

It also targets word depth, since modifying an entry

requires an understanding of the lexical information

it contains; Do not Shoot the Messenger rewards the

number of messages posted by learners in a group lex-

icon. This badge promotes social exchanges between

learners, facilitating collaboration on the group’s lex-

icon; Mighty Commentator rewards the number of

comments posted by learners in a group lexicon. As

comments are linked to the content of an entry, this

badge favors collaborative work.

All these elements are displayed on the homepage

Spread the Word! BaLex, A Gamified Lexical Database for Collaborative Vocabulary Learning

393

of the application in a summarized version (see Fig.

3) and the details are available on a dashboard.

Figure 3: Summarized game elements displayed on the

homepage.

These game elements are meant to maintain mo-

tivation and engagement in a vocabulary notebook

type of task, and to give cues regarding vocabulary

learning methodology, by drawing attention to vari-

ous ways in which the learner can deepen their knowl-

edge of one given word.

7 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we propose the gamified vocabulary

notebook BaLex. It was designed to promote vo-

cabulary learning by supporting collaboration among

learners, enhancing their motivation and favouring

autonomous learning. This software provides lexical

information from the Wiktionary and lets users adapt

the content of their different notebooks according to

their learning curriculum.

Features such as managing labels, deadlines and

word sorting are designed to facilitate the organiza-

tion and learning of word lists. Group lexicons pro-

vide group chats and allow to comment every block

in entry pages. Both features are intended to foster

collaboration, and we hypothesize it will have a posi-

tive effect on both learner motivation and vocabulary

learning. Game elements are also implemented to en-

hance learner motivation and provide methodological

guidance regarding vocabulary learning.

Teachers can easily monitor their students by cre-

ating groups for their classes. Their role as admin-

istrator in the group allows them to view the work

carried out in individual and group lexicons, as well

as give instructions and feedback. As literature sug-

gests it, we expect it to improve learners’ vocabulary

skills. Indeed, vocabulary learning requires method-

ology and strategies on the part of learners (Nation,

2013), and the presence of the teacher will foster con-

tinuity between learning in the classroom and out-

side, on their own. In this way, the tool can be in-

tegrated into the school curriculum, providing a link

between classroom teaching practices and the au-

tonomous learning of vocabulary expected.

BaLex is meant to be integrated more closely in a

workflow involving various applications. We provide

a dedicated Application Programming Interface (API)

that allows to extend the learners’ vocabulary outside

of the notebook application. As part of our future

works, we will plug BaLex with external tools such as

vocabulary learning games, flashcards applications,

reader assistants, or other vocabulary learning appli-

cation. Connecting more deeply the different appli-

cations via the BaLex API will contribute to creating

a complete learning ecosystem organised around the

vocabulary notebooks. We will also enrich the gami-

fied indicators with more information on the learners’

activities carried out in the different applications to

provide a deep feedback on their progress and rele-

vant rewards. Finally, another perspective is the inte-

gration of new languages in BaLex, which currently

only operate with the English words from the English

Wiktionary.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the LABEX ASLAN of Univer-

sit

´

e de Lyon (ANR–10–LABX–0081) for its finan-

cial support as part of the french program “Investisse-

ments d’Avenir” managed by the Agence Nationale

de la Recherche (ANR). They also thank Ameni Tlili

for her help in collecting the data.

REFERENCES

A. Al-Jasir, M. (2019). Computer Assisted Vocabulary

Learning: A Case Study on EFL Students at Al-Imam

Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University. Arab World

English Journal, (249):1–63.

Alfadil, M. (2020). Effectiveness of virtual reality game in

foreign language vocabulary acquisition. Computers

& Education, 153:103893.

Alqahtani, M. (2015). The importance of vocabulary in lan-

guage learning and how to be taught. International

Journal of Teaching and Education, 3(3):21–34.

Barcomb, M. and Cardoso, W. (2020). Rock or Lock? Gam-

ifying an online course management system for pro-

nunciation instruction: Focus on English /r/ and /l/.

CALICO Journal, 37(2):127–147.

Bastien, C. and Scapin, D. (2004). La conception de logi-

ciels interactifs centr

´

ee sur l’utilisateur :

´

etapes et

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

394

m

´

ethodes. In Falzon, P., editor, Ergonomie, pages

451–462. Paris, 1 edition.

Benson, P. (2013). Teaching and Researching: Autonomy

in Language Learning. London, 2 edition.

Bueno-Alastuey, M. C. and Nemeth, K. (2020). Quizlet and

podcasts: effects on vocabulary acquisition. Computer

Assisted Language Learning, 0(0).

Chukharev-Hudilainen, E. and Klepikova, T. A. (2016). The

effectiveness of computer-based spaced repetition in

foreign language vocabulary instruction: a double-

blind study. CALICO Journal, 33(3):334–354.

Deterding, S., Sicart, M., Nacke, L., O’Hara, K., and Dixon,

D. (2011). Gamification. using game-design elements

in non-gaming contexts. In Proceedings of the 2011

annual conference extended abstracts on Human fac-

tors in computing systems - CHI EA ’11, page 2425,

Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Dumas Reyssier, S., Serna, A., Hallifax, S., Marty, J.-C., Si-

monian, S., and Lavou

´

e, E. (2023). How does adaptive

gamification impact different types of student motiva-

tion over time? Interactive Learning Environments,

0(0):1–20.

Farangi, M., Nejadghanbar, H., Askary, F., and Ghor-

bani, A. (2015). The effects of podcasting on EFL

upper-intermediate learners’ speaking skills. CALL-

EJ, 16:1–18.

Freund, F. (2016). Pratiques d’apprentissage

`

a distance dans

une formation hybride en Lansad – Le juste milieu en-

tre contr

ˆ

ole et autonomie. Alsic, 19(2).

Ginanjar Anjaniputra, A. and Salsabila, V. (2018). The mer-

its of quizlet for vocabulary learning at tertiary level.

Indonesian EFL Journal, 4:1.

Hallifax, S., Serna, A., Marty, J.-C., and Lavou

´

e, E. (2018).

A Design Space For Meaningful Structural Gamifica-

tion. In Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI

EA ’18, pages 1–6, New York, NY, USA.

Hao, T., Wang, Z., and Ardasheva, Y. (2021). Technology-

Assisted Vocabulary Learning for EFL Learners: A

Meta-Analysis. Journal of Research on Educational

Effectiveness, 14(3):645–667.

Hwang, G.-J. and Wang, S.-Y. (2016). Single loop or dou-

ble loop learning: English vocabulary learning perfor-

mance and behavior of students in situated computer

games with different guiding strategies. Computers &

Education, 102:188–201.

Klimova, B. (2021). Evaluating Impact of Mobile Applica-

tions on EFL University Learners’ Vocabulary Learn-

ing – A Review Study. Procedia Computer Science,

184:859–864.

Laufer, B. (1992). How Much Lexis is Necessary for Read-

ing Comprehension? In Arnaud, P. J. L. and B

´

ejoint,

H., editors, Vocabulary and Applied Linguistics, pages

126–132. London.

Lavou

´

e, E., Monterrat, B., Desmarais, M., and George, S.

(2019). Adaptive Gamification for Learning Environ-

ments. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies,

12(1):16–28.

Lin, J.-J. and Lin, H. (2019). Mobile-assisted ESL/EFL

vocabulary learning: a systematic review and meta-

analysis. Computer Assisted Language Learning,

32(8):878–919.

Lin, P. (2022). Developing an intelligent tool for computer-

assisted formulaic language learning from YouTube

videos. ReCALL, 34(2):185–200.

Ma, Q. (2017). Technologies for Teaching and Learning L2

Vocabulary, chapter 4, page 45–61.

Manzo, A. V. and Sherk, J. K. (1971). Critical Perspectives

in Reading: Some Generalizations and Strategies for

Guiding Vocabulary Learning. Journal of Reading Be-

havior, 4(1):78–89.

Nation, I. S. P. (1999). Teaching and learning vocabulary.

Boston, Mass, nachdr. edition.

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning Vocabulary in Another

Language. Cambridge Applied Linguistics. 2 edition.

Nishioka, H. (2020). Learning Technology Review: Vocab-

ulary.com. CALICO Journal, 37(2):205–212.

Norman, D. (2013). The design of everyday things. Re-

vised and expanded edition (formerly psychology of

everyday things) edition.

Oxford, R. and Crookall, D. (1990). Vocabulary Learn-

ing: A Critical Analysis of Techniques. TESL Canada

Journal, 7(2):09–30.

Rausch, S. (1969). Enriching vocabulary in secondary

schools, pages 191–200. International Reading As-

sociation, Newark.

Teng, F. (2014). Research Into Practice: Strategies for

Teaching and Learning Vocabulary. Beyond Words,

2:41–57.

Tremblay, O. and Anctil, D. (2020). Introduction. —

Recherches actuelles en didactique du lexique :

avanc

´

ees, r

´

eflexions, m

´

ethodes. Lidil. Revue de lin-

guistique et de didactique des langues, (62).

Tremblay, O., Anctil, D., and Perron, V. (2016). Vers un

mod

`

ele de la comp

´

etence lexicale en didactique du

lexique.

Trim, J., editor (2002). Cadre europ

´

een commun de

r

´

ef

´

erence pour les langues: apprendre, enseigner,

´

evaluer — guide pour les utilisateurs. Division des

Politiques Linguistiques, Strasbourg.

Tseng, W.-T. and Schmitt, N. (2008). Toward a Model of

Motivated Vocabulary Learning: A Structural Equa-

tion Modeling Approach. Language Learning 58:2.

Wang, F., Zhang, R., Zou, D., Au, O., Xie, H., and Wong, L.

(2021). A review of vocabulary learning applications:

From the aspects of cognitive approaches, multimedia

input, learning materials, and game elements. Knowl-

edge Management and E-Learning, 13(3):250–272.

Ye, S. X., Shi, J., and Liao, L. (2023). An evaluative review

of mobile-assisted l2 vocabulary learning approaches

based on the situated learning theory. Journal of Cur-

riculum and Teaching.

Yu, A. and Trainin, G. (2022). A meta-analysis examining

technology-assisted L2 vocabulary learning. ReCALL,

34(2):235–252.

Zou, D., Huang, Y., and Xie, H. (2021). Digital game-based

vocabulary learning: where are we and where are we

going? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(5-

6):751–777.

Spread the Word! BaLex, A Gamified Lexical Database for Collaborative Vocabulary Learning

395