Shifting from Traditional to Alternative Assessment Methods in

Higher Education: A Case Study of Norwegian and Italian

Universities

Alexandra Lazareva

1

and Daniele Agostini

2

1

Department of Education, University of Agder, Universitetsveien, Kristiansand, Norway

2

Department of Psychology and Cognitive Science, University of Trento, Corso Bettini, Rovereto, Italy

Keywords: Higher Education, Traditional Assessment Methods, Alternative Assessment Methods.

Abstract: The background of this study is the growing focus on so-called “student-active” or “student-centered” learning

and teaching methods, which have demonstrated to improve students’ learning outcomes and soft skills.

However, despite the benefits of these methods, much university teaching still relies on final high-stakes

summative examinations, which may lead to students’ lack of engagement in learning activities during the

semester and increased focus on the preparation for the final exam. This paper is aimed at exploring the

traditional and alternative assessment methods used in higher education in Norway and Italy and focuses on

two research questions: (1) What are the different types of student assessment involved at universities in

Norway and Italy? and (2) What are the benefits and challenges related to alternative assessment formats in

higher education when compared to the traditional ones? To answer the first question, the assessment forms

used in selected units at a university in Norway and Italy were mapped out. To answer the second question,

six university instructors with experience in alternative assessment were interviewed. The results contribute

to a better understanding of the factors motivating instructors to transition to alternative assessment, as well

as possible barriers for the implementation of alternative assessment.

1 INTRODUCTION

International efforts in higher education (HE) reflect

a widespread recognition of the need for educational

systems to evolve, underscoring a global movement

towards more interactive and student-centred

learning environments, especially at the HE level,

which seems to lag behind other educational levels in

this respect (Børte et al., 2023). Across the globe,

educational institutions are exploring innovative

teaching methods and assessment strategies that go

beyond traditional approaches (Fraser, 2019; Puranik,

2020).

These global trends reflect a growing consensus

that education should not only focus on knowledge

acquisition but also on developing critical thinking

and problem-solving skills (Hitchcock, 2022).

In Norway, much focus has been put on so-called

“student-active learning and teaching methods”

which require HE institutions to break away from

one-way communication by the teacher and employ

more practical methods such as cases, discussions,

and participation in research (Meld. St. 16, 2020-

2021). The same is true for Italy, where the creation

of Teaching Learning Centres and Digital Education

Hubs is at the core of the NRRP (the Next Generation

EU-funded National Recovery and Resilience Plan)

effort. This should be the major impulse towards a

transformation in Italian’s HE teaching practice after

several laws and guidelines that served as precursors,

such as "Reform of university and research" (Legge

30 dicembre 2018, n. 145), "Guidelines for the quality

of university teaching" (Ministero dell'Università e

della Ricerca, 2019), "Guidelines for the evaluation

of university teaching" (ANVUR, 2020) and "Report

on the quality of university teaching" (ANVUR,

2021, periodically published).

However, both in Norway and Italy, despite a

continuous and ongoing debate among HE

institutions’ leadership, previous research suggests

that high-stakes final exams are still the most used

form of TA (Gray & Lazareva, 2022; Grion &

Serbati, 2019). Relying on final high-stakes

summative exams as the basis for grading may limit

Lazareva, A. and Agostini, D.

Shifting from Traditional to Alternative Assessment Methods in Higher Education: A Case Study of Norwegian and Italian Universities.

DOI: 10.5220/0012623300003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 2, pages 533-540

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

533

students’ opportunities to demonstrate their

knowledge and skills holistically, which can lead to

reduced motivation to engage in learning activities

and increased focus on exam preparation.

This paper focuses on two research questions: (1)

What are the different types of student assessment

involved at universities in Norway and Italy? (RQ1)

and (2) What are the benefits and challenges related

to alternative assessment formats in higher education

when compared to the traditional ones? (RQ2)

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2

provides a brief overview of related research and

introduces the background of this study. Method is

outlined in Section 3. Section 4 presents the results of

the study, which are further discussed in Section 5.

Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

RESEARCH

Research in HE has demonstrated that student-active

learning methods have the potential to foster higher-

order thinking skills, including analysis, synthesis,

and evaluation thus improving students' learning

outcomes (Komulainen et al., 2015). The design of

those approaches is also beneficial for the

development of soft skills, such as collaboration,

presentation, and assessment (Godager et al., 2022).

Students perceive these methods as motivating and

supportive of knowledge acquisition (Langsrud &

Jørgensen, 2022).

As the education landscape evolves towards more

interactive and student-centered learning

environments, it is crucial to adapt assessment

methods accordingly (Gibson & Shaw, 2011; Hand,

Sanderson & O'Neil, 2015). Relying solely on

traditional assessment (TA) approaches such as

multiple-choice questions or final exams with short

answers falls short when it comes to evaluating skills

development, critical thinking, and problem-solving

abilities (Bryan & Clegg, 2019).

To ensure that assessment practices are effective,

it is essential to be mindful of the principles of

constructive alignment. This means that teaching

activities and assessment tasks should directly

support the intended learning outcomes, and the type

of assessment employed should be influenced by the

desired learning outcomes (Biggs, 2014).

According to Wiggins (1990), the principles of

authentic assessment need assignments that prompt

students to apply their newfound knowledge by

performing, creating, or producing something that

reflects the complexity of real-world scenarios. By

incorporating these theoretical frameworks into

alternative assessment methodologies, educators can

better align evaluation practices with desired learning

objectives, leading to more profound comprehension

and more precise evaluations of student competence.

Furthermore, in the last year, the use of artificial

intelligence (AI) in HE, such as for essay writing, has

further complicated the concept of final exams,

forcing institutions and instructors to rethink the way

of assessing students’ products (Agostini & Picasso,

2023; Rudolph, Tan & Tan, 2023). Some universities

have temporarily returned to traditional pen-and-

paper exams while searching for a way to redesign

student assessment. Alternative assessment (AA) and

innovative methods are needed in this conjuncture to

address the rising complexity of the educational

landscape (Bryan & Clegg, 2019).

This paper aims to provide a better understanding

of both TA and AA methods, as well as explore some

of the possible barriers for the implementation of AA

methods in Norway and Italy. Additionally, the paper

aims to identify the factors that motivate instructors

to transition from TA to AA. By discussing the

findings from the two countries, this paper aims to

contribute to a better understanding of the

complexities involved in shifting from TA to AA

methods.

3 METHOD

This section outlines the methods of data collection

and analysis used in the study and addresses some of

the study’s limitations.

3.1 Data Collection

To answer RQ1, the assessment forms used at a

Faculty of Business and Law at one university in

Norway and a Department of Economy and

Management at one university in Italy were mapped

out. This choice was made because the two units were

comparable in terms of the subject areas that were

covered by the course offers. In addition, the two

units were not too different in terms of size. To map

out the assessment forms, the course syllabi available

online were analysed (total N=378).

To answer RQ2, semi-structured interviews with

six university instructors were carried out (three in

Norway and three in Italy). The informants were

chosen using the snowball sampling method. The key

criteria (besides the informants’ availability and

willingness to participate) was the informants having

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

534

experience with alternative assessment methods in

HE. The interview guide consisted of three sections:

background questions focusing on the informants’

teaching experience, informants’ experiences with

traditional assessment (TA) formats, and informants’

experiences with alternative assessment (AA)

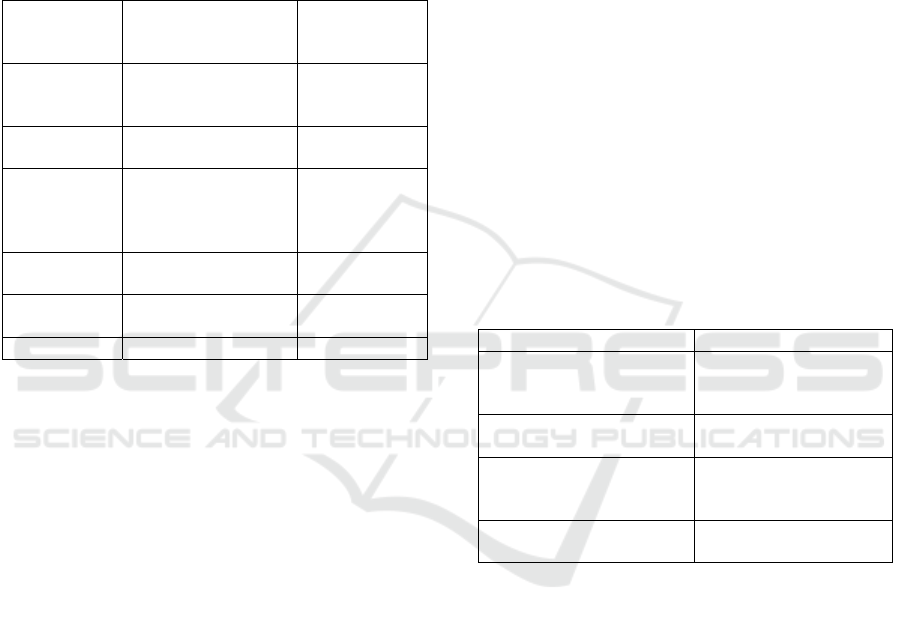

formats. Table 1 presents an overview of the

informants’ teaching background (the informants

were assigned fictitious names).

Table 1: Informants’ teaching background.

Informant Years of experience

teaching at

universit

y

Subject area

Markus

(Norway)

20+ ICT, human-

computer

interaction

Henrik

(

Norwa

y)

20 History

Walter

(Norway)

3 Religion,

philosophies

of life and

ethics

Giulia (Italy) 21 Economy and

management

Cecilia

(

Ital

y)

26 Economy and

mana

g

ement

Sara

(

Ital

y)

10 Education

This project was approved by NSD (Norwegian

Centre for Research Data). The interviews were audio

recorded and manually transcribed afterwards.

3.2 Data Analysis

To analyse the interviews, the content analysis

method was employed. The inductive approach was

chosen as the objective was to explore and understand

the phenomenon rather than draw any generalizations

(Forman & Damschroder, 2008). One of the benefits

of qualitative content analysis is that the lack of a

theory-led hypothesis makes it possible to learn from

the informants without imposing predefined

categories on them (Hseih & Shannon, 2005).

3.3 Limitations

An important limitation that must be considered when

discussing the results of this research is that even

though many courses in Norwegian universities

employ final high-stakes summative exams, many

instructors make use of compulsory assignments that

students must complete during the semester to be able

to sit for the exam. Such compulsory assignments

may be of the formative character (e.g., students

working on the same project throughout the semester

with feedback from the instructor and peers). This

information is not always available in the course

description published online. In Italy, there is no such

type of compulsory assignments for most of the

courses, except for some mandatory attendance

courses that might implement a similar approach if

clearly stated in the syllabus.

It must also be mentioned that the data were

collected for the academic year of 2022. With the

arrival of ChatGPT in late 2022, many instructors

made modifications to the assessment formats in the

following year.

4 RESULTS

To answer RQ1, this section presents an overview of

the assessment forms used at a Faculty of Business

and Law at a university in Norway, where 132 course

syllabi were analysed, and a Department of Economy

and Management at a University in Italy, where 246

course syllabi were analysed (see Table 2).

Table 2: An overview of assessment forms used in selected

units at universities in Norway and Italy.

University in Norway University in Italy

Written school

examination format

(

47,8%

)

Written school

examination format

(

52,3%

)

Portfolio assessment

(20,5%)

Oral assessment

(23,5%)

Term paper/project

examination format

(14,4%)

Portfolio examination

(14,7%)

Take-home examination

(9,1%)

To answer RQ2, the interview transcripts were

analysed. The analysis was done in three rounds: (1)

Each of the two researchers coded three of the

interviews and summarised the results in the form of

a concept map with excerpts from the interviews as

examples; (2) The researchers compared and

discussed the results, eliminating repetitions,

reformulating the names of some of the categories

and codes, and merging the categories and codes each

of us has developed; (3) Each of the two researchers

went back to the interview transcripts comparing the

content of the interviews against the coding scheme

and suggesting final minor edits to fine-tune the

overview of the results. As a result, four main

categories were distinguished: (1) the problem of

definitions, (2) traditional assessment (TA) forms, (3)

alternative assessment (AA) forms, and (4) the

Shifting from Traditional to Alternative Assessment Methods in Higher Education: A Case Study of Norwegian and Italian Universities

535

informants’ general reflections. Categories 2 and 3

were further divided in several sub-categories.

Below, each of the categories is discussed in detail,

and sub-categories are presented.

4.1 The Problem of Definitions

One of the issues that Norwegian informants

repeatedly mentioned was how to define which

assessment formats are to be considered traditional

and which ones can be called alternative. For

example, one of the informants reflected that a written

exam may be both traditional or alternative depending

on what kind of questions the students are asked,

whether the question is aimed at memorising and

reproducing the knowledge or, on the other hand,

applying the knowledge and creating something new.

In contrast, Italian informants never challenged the

interviewer’s assumption of what is traditional and

what is alternative assessment in their contexts. They

seem to be comfortable with these definitions and

distinguish them without overlap and ambiguity.

The different informants also had different

thoughts when it came to students having access to all

resources during the exam. Some informants

considered it a usual and rather traditional practice,

while others viewed it as something more innovative.

4.2 Traditional Assessment Forms

This category included three sub-categories:

examples of TA forms, benefits of TA forms, and

challenges related to TA forms. Each sub-category is

presented below.

4.2.1 Examples of Traditional Assessment

Forms

The informants had various examples of TA formats

they have employed in their teaching, such as written

exams, multiple-choice tests, online quizzes/tests,

continuous assessment tests (CATs), project reports,

demos, plenary presentations, oral exams, student

lectures, questions and answers (Q&A), short essays,

long essays, and digital written home exams (i.e.,

those where students produce linear texts).

4.2.2 Benefits of Traditional Assessment

Forms

A major benefit that was mentioned by most of the

informants is that the TA formats set clear boundaries

for the students and help them focus on the parts of

the syllabus that are of key importance. For example,

Markus noted: “… when they know they have a

traditional exam, like a sitting written exam, they

really tend to prepare a lot […], at least it really forces

the students to study to learn what they have to learn;

it sets very clear limited boundaries of what they

should learn”.

Thus, there was an agreement among the

respondents that TA forms are straightforward to

design, manage, and grade. This is especially relevant

for large classes and becomes even more efficient

when it is possible to involve technology for

automated grading. Sara said: “You can assess

knowledge, and you can easily scale up to 200

students; one of my courses has 200 students. You

can easily scale up to 100 students this kind of

questions, and if you use the technology, for example

the online computer-based assessment, you can

actually get the automatic correction, so that’s for

sure a very effective way to assess knowledge”.

TA forms are seen as an effective way to assess

factual knowledge, ensure that all students have

studied the course material, as well as prevent free

riding in group work. One of the informants noted

that written exams can be a good format for

evaluating students’ reflection as well.

4.2.3 Challenges Related to Traditional

Assessment Forms

A major challenge related to TA forms reported by

the informants was students focusing primarily on

what is going to be on the exam, which increases the

risk of students just memorising, only doing the

minimum required input to pass the exam and likely

forgetting the material soon after the exam. Cecilia

maintained that: “… students should not just have to

process concepts and repeat things back, especially at

master's level, but also in the bachelor's, know-how,

and to know how to do is key. That's it. This is my

point of view.”

Time limitation was described as another

challenge. One of the informants discussed that what

a student can demonstrate during a set time frame

(e.g., a 30-minute oral examination, or a 4-hour

written exam) is extremely limited, which often

makes it challenging to claim that the student’s

competence was assessed in a fair way. Another issue

is the limitations introduced by the chosen format

itself. Here, the informants mentioned students

struggling with dyslexia or writing in general, or

experiencing anxiety during oral examinations which

reduces their performance overall.

Finally, another limitation reported by the

informants lies in the fact that TA formats focus

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

536

primarily on content rather than students’ skills,

applied knowledge or critical thinking.

4.3 Alternative Assessment Forms

This category included three sub-categories:

examples of AA forms, instructor’s motivation to

employ AA, and instructor’s experiences of AA. Each

sub-category is presented below.

4.3.1 Examples of Alternative Assessment

Forms

Various examples were discussed by the informants,

such as different forms of portfolio assessments, peer

teaching, writing blogs (with less structure provided

by the instructor), students grading their own exams,

students developing an assessment instrument (e.g.,

questionnaire), roleplay, students recording

themselves teaching with a 360 camera, group

projects, participation in expert seminars,

presentations, online quizzes/tests, peer feedback,

and creating a digital story. In the latter, the students

were required to use a combination of Creaza and

PowerPoint to discuss a challenging classroom

situation using the theories from the course syllabus.

Some other examples of digital tools used for AA

were Moodle (as a platform to facilitate AA

activities) and Google Drive, which was used both for

collaboration and submissions.

Another example of AA which was mentioned by

Markus is drop-in examinations, where a student

could themselves select and book a time slot at the

instructor’s office to take the exam. Then, random

questions would be given to the student from a large

question database, and if the student was not satisfied

with the result, it was possible to retake the exam at a

later point of time during the semester. Markus

discussed that even though he did not employ the

drop-in examination himself, he borrowed the

element of flexibility from this examination format

into his own teaching. Namely, he chose to pay less

attention to the deadlines during the semester and

instead let the students choose themselves which

portfolio assignment to start with and when to deliver

during the semester.

Another example described by Henrik was an

individualized exam, where the instructor let the

students choose from four formats (Q&A, giving a

lecture, three short essays or one long essay). Yet

another informant talked about personalising the

exam topic based on students’ practical experiences.

4.3.2 Instructor’s Motivation to Employ

Alternative Assessment

Here, both factors related to intrinsic and extrinsic

motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000) were mentioned.

When it comes to the former, the informants reflected

that they wanted to individualise the exams for the

students to help them better understand and apply

concepts, as well as demonstrate a better performance

in the exam situation. Giulia reported her willingness

to let the students to really connect with the matter of

the course: “[…] the goal was more to work on

learning to use these things. Not so much learning to

repeat them, so this was my transition and leaving

them a bit more free to experiment because, for

example, in the first year I don't give them companies

[as case studies], I tell them «Choose the one you

want», and so it seemed to me to give them a

motivation linked to passions too, someone tells me

«My uncle has a tavern», I say «Okay, do your uncle's

company»”.

Another commonly reported reason is related to

the instructors noticing that specific students struggle

with specific formats such as oral examination or

written exams. For example, Markus reflected: “I had

some students in the class… and my classes are

usually small… some students are very clever when

it comes to being creative. Then I give them a written

exam and they are hardly getting 60% or 50-

something % because I was asking them in the way

they weren’t used to think or create. It made me very

sad the first three years, why students aren’t doing

well... They didn’t fail per se, but they didn’t do well.

And they were clever.” Henrik said: “[…] there are

students I have experienced who come to oral

examinations, when this is the only option, being

extremely nervous and, of course, this influences their

performance and the grade, and it’s not fair. There are

also students who have dyslexia or, you know, other

difficulties that, you know, are kind of a brake in their

performance either in oral examinations or written

examinations, when you only follow one traditional

method of assessing the students”.

However, factors related to extrinsic motivation

were also mentioned: Walter was asked to develop an

AA format involving digital tools as part of the course

description when he overtook the course.

4.3.3 Instructor’s Experiences of Alternative

Assessment

There was a general agreement among the informants

that AA formats are overall more expensive as they

imply more workload for the instructor during the

Shifting from Traditional to Alternative Assessment Methods in Higher Education: A Case Study of Norwegian and Italian Universities

537

semester. In addition, AA forms can be rather

difficult to manage. For example, not all colleagues

in the group may be comfortable with AA formats or

employing new digital tools in their assessment.

Moreover, the IT systems used at the university may

not be designed to support AA forms. For example,

the system may require the instructors to specify one

deadline for the students to deliver the exam by –

while some AA forms may imply that students are

free to choose a date during the semester themselves

or deliver parts of the assessment continuously during

the semester. In a similar way, it may be difficult to

individualise the exam where students can choose the

format of the examination, because the IT system

would normally require the instructor to specify one

format (e.g., an oral examination). AA forms,

therefore, often require closer collaboration with the

exam and/or administration unit at the university.

Moreover, mastering a new assessment format is

also learning. Thus, this can be seen as “stealing” time

from working on the course content itself. Here,

Walter discussed specifically the digital story exam

and reflected on various challenges related to that

format. First, the time limitation made it difficult for

the students to properly discuss the subject. In

addition, many students did not focus enough on

presenting their story in an engaging way; instead,

they read the script monotonously. Walter said: “[…]

transitioning from the written to oral format is more

demanding than one might think. Most students who

completed this assignment most likely had written

down the whole script at first and then read it out loud

while recording the PowerPoint presentation. […]

And then the whole oral presentation sounds like

there is someone just sitting down and reading which

is not engaging to listen to. It becomes more

monotonous than it could have been”. In addition,

formalities such as structure and proper referencing

seemed to have taken much of students’ focus.

While the informants reflected that with AA the

students had a very good performance overall and that

AA seems to contribute to the development of

students’ soft skills, some of the informants also

mentioned that they have had to step away from the

AA formats due to the limitations discussed above.

4.4 General Reflections

This section presents other reflections made by

informants that did not fall under any of the categories

mentioned above. First, some of the informants

reflected that all assessment formats can be good if

they are designed and implemented as an organic part

of the learning process, which reflects the concept of

constructive alignment (Biggs, 2014). What is of key

importance here is that assessment should target both

content knowledge and metacognitive knowledge

(i.e., help students understand how they learn). Thus,

as Markus noted, one of the issues where more

research is needed is how to create good exam

questions and how to assess students’ soft skills such

as collaboration and critical thinking.

The informants also note that it is good practice

for students to experience various assessment formats

and demonstrate their competence in different ways,

and not only through the traditional written linear

texts or oral Q&A type of examination.

One major challenge that Walter discussed is the

increased focus on grading criteria which may lead to

increased instrumentalism in teaching and learning:

“One is often caught in the expectation that one must

be in line with something… such as what the sensor

or the one who created the exam assignment thought

when they gave that assignment; so, one is going to

try to sort of approach as close as possible the

objectives that the assignment creator thought of […],

there is a kind of an expectation that one who created

the objective already has an idea of how all students

should reach that objective. And this implies a certain

form of instrumentalism, doesn’t it, where everything

in one way or another is in the instructor’s or teacher’s

head (or the one who created the task) and then

everything is about how close the student can

approach this understanding in one way or another

[…]”. According to Walter, this is a challenge

especially because students are often expected to

show more independence in their reflection and

discussion of their own standpoints.

The informants also reflected that AA can be

“messy” and, therefore, it requires good planning. It

is also important to communicate to students why this

specific form of assessment is going to be used. Some

other issues that informants raised concerned

involving AI in assessment in a good way. Some of

the informants reflected that there is a need for

improving tools for teacher and peer feedback, and

this is where more research is needed on the use of AI

for semi-automated feedback.

5 DISCUSSION

The results of this research project demonstrate that

TA is prevalent in HE in Norway and Italy. Both

countries share similar issues when it comes to

student assessment (e.g., administrative issues and

instructor workload), but Norway seems to have a

wider variety of AA assessment methods in place. AA

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

538

often depends on the individual instructors’

motivation and requires extra work hours to design

and implement. This aligns with earlier research

reporting on such barriers for AA in HE as policy

barriers, institutional change, and resources (Gray &

Lazareva, 2022). While there was an overall

agreement among the informants on the pedagogical

benefits of AA methods (e.g., improved student

performance and the development of students’ soft

skills), some of the informants also admitted that they

have had to step away from using the AA methods

due to such limitations as increased workload.

Moreover, the informants also supported the view

that there is a need for teachers’ professional

development, clearer university guidelines and

flexibility. According to the informants, AA often

requires an even closer collaboration with the exam

and/or administration unit at the university, as well as

the IT department, which adds to the extra workload.

This trend seems to be global, underlining how efforts

for active learning and AA should be supported by the

institution at different levels such as at the

administrative and organisational one (Griffith &

Altinay, 2020; Ujir et al., 2020). Experiences in other

countries, such as the Netherlands, Denmark,

Singapore, and the USA, suggest that strong

organisational support, specific program

management and custom curriculum development

might be needed to allow a wide and sustainable

adoption of active teaching and AA methods (Li,

2022; Tan, 2021).

Another important aspect to note is that the

informants in this research project have experience

with teaching in different subject areas. This may

have contributed to the fact that different

understandings of what AA entails were reported.

This demonstrates that there is more work to be done

for HE instructors to reach a common understanding

of the types of student assessment. Moreover, in

courses taught by several instructors, extra effort may

be necessary for all the instructors involved in

teaching and assessment to have a positive view on

the AA method that is being used, as well as an

appropriate level of training if there is a new digital

technology involved.

Finally, there has been a growing interest among

university instructors regarding the role of AI in

assisting them. This enhanced interest highlights the

perceived advantages of using AI to streamline time-

consuming tasks in AA methods. With such

assistance, it is possible that AA methods and

constructive alignment will become more sustainable

(Agostini, 2024).

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presents the results of an explorative

research project aiming to map out and describe the

different traditional and alternative assessment forms

used in HE in Norway and Italy, as well as discuss the

benefits and challenges related to AA formats in HE

when compared to the traditional ones. To answer

RQ1, the assessment forms used at the Faculty of

Business and Law at a university in Norway and the

Department of Economy and Management at a

university in Italy were mapped out (see Table 2). To

answer RQ2, semi-structured interviews with three

university instructors in Norway and three university

instructors in Italy were carried out. There was an

agreement among the informants participating in the

study that TA forms are easy to design and

administrate. While TA forms are suitable for

assessing students’ factual knowledge, they may not

always be well-suited for addressing students’ skills,

applied knowledge, or critical thinking. Moreover,

time and format limitations may make it challenging

to fairly assess students’ competence. The

informants’ intrinsic motivation to individualise the

assessment format for their students was often the

main drive to implement AA. While the informants

reported positive experiences with AA overall,

especially in terms of student performance and the

development of students’ soft skills, several of the

informants admitted that they had to step away from

AA due to the increased workload related to the

design and administration of AA.

The results of the interviews suggest several

potential areas for future research, such as (1)

reaching a common understanding of what

“traditional” and “alternative” assessment entails, (2)

exploring the potential of AI technology in assisting

instructors in AA methods, (3) developing

assessment methods that would target both students’

content and metacognitive knowledge, and (4)

exploring in what ways the formulation of the grading

criteria may affect students’ performance in different

types of assignments and exams.

This research project primarily describes the

results and outlines some similarities and differences

in HE in Norway and Italy. In the future, we aim at

carrying out comparative research, which will imply

a closer analysis of the Norwegian and Italian

education systems and, more specifically, assessment

culture in HE. This will make it possible to initiate a

deeper and more nuanced discussion around HE

student assessment in the two countries.

Shifting from Traditional to Alternative Assessment Methods in Higher Education: A Case Study of Norwegian and Italian Universities

539

REFERENCES

Agostini, D. (2024). Are Large Language Models Capable

of Assessing Students’ Written Products? A Pilot Study

in Higher Education. Research Trends in Humanities,

Education & Philosophy, 11, 38-60.

Agostini, D., & Picasso, F. (2023). Large Language Models

for Sustainable Assessment and Feedback in Higher

Education: Towards a Pedagogical and Technological

Framework. Proceedings of the First International

Workshop on High-Performance Artificial Intelligence

Systems in Education Co-Located with 22nd

International Conference of the Italian Association for

Artificial Intelligence (AIxIA 2023). AIxEDU 2023

High-performance Artificial Intelligence Systems in

Education, Aachen. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3605/

ANVUR (2020). Linee guida per la valutazione della

didattica universitaria. Roma, IT.

ANVUR (2021). Rapporto sulla qualità della didattica

universitaria. Roma, IT.

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive

alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347-364.

Biggs, J. (2014). Constructive alignment in university

teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 1, 5-

22.

Børte, K., Nesje, K., & Lillejord, S. (2023). Barriers to

student active learning in higher education. Teaching in

Higher Education, 28(3), 597-615.

Bryan, C., & Clegg, K. (Eds.). (2019). Innovative

assessment in higher education: A handbook for

academic practitioners. Routledge.

Forman, J., Damschroder, L. (2008). Qualitative content

analysis. In: Jacoby, L., Siminoff, L.A. (eds.) Empirical

Methods for Bioethics: A Primer, pp. 39–62. Elsevier

Publishing, Oxford.

Fraser, S. (2019). Understanding innovative teaching

practice in higher education: a framework for

reflection. Higher Education Research &

Development, 38(7), 1371-1385.

Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2004). Conditions under which

assessment supports students’ learning. Learning and

Teaching in Higher Education, 1, 3-31.

Gibson, K., & Shaw, C. M. (2011). Assessment of active

learning. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of

International Studies.

Godager, L. H., Sandve, S. R., & Fjellheim, S. (2022).

Studentaktive læringsformer i høyere utdanning i

emner med stort antall studenter. Nordic Journal of

STEM Education, 6(1), 28–40.

Governo Italiano (2018). Legge 30 dicembre 2018, n. 145.

Riforma dell'Università e della Ricerca. Gazzetta

Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana.

Gray, R., Lazareva, A. (2022). When the past and future

collide: Digital technologies and assessment in

Norwegian higher education. In S. Hillen, P. Wolcott,

C. Schaffer, A. Lazareva, & R. Gray (Eds.), Assessment

Theory, Policy, and Practice in Higher Education:

Integrating Feedback into Student Learning, pp. 39-58.

Waxmann Verlag.

Griffith, A. S., & Altinay, Z. (2020). A framework to assess

higher education faculty workload in US

universities. Innovations in education and teaching

international, 57(6), 691-700.

Grion, V., & Serbati, A. (2019). Valutazione sostenibile e

feedback nei contesti universitari. Prospettive

emergenti, ricerche e pratiche. Lecce:

PensaMultimedia.

Hand, L., Sanderson, P., & O'Neil, M. (2015). Fostering

deep and active learning through assessment.

In Accounting Education Research (pp. 71-87).

Routledge.

Hitchcock, D. (2022). Critical thinking. In Edward N. Zalta

& Uri Nodelman (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition). Metaphysics

Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved at:

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/crit

ical-thinking/

Hseih, H.-F., Shannon, S.E. (2005). Three approaches to

qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res, 15(9),

1277–1288.

Komulainen, T. M., Lindstrøm, C., & Sandtrø, T. A. (2015).

Erfaringer med studentaktive læringsformer i

teknologirikt undervisningsrom. UNIPED, 38(4), 363–

372.

Langsrud, E., & Jørgensen, K. (2022). Studentaktiv læring

i juridiske emner. UNIPED, 45(3) 171–183.

Li, H. (2022). Educational change towards problem based

learning: An organizational perspective. River

Publishers.

Meld. St. 16 (2020-2021). Utdanning for omstilling – Økt

arbeidslivsrelevans i høyere utdanning. Kunnskaps-

departementet. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/doku

menter/meld.-st.-16-20202021/id2838171/

Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca. (2019). Indirizzi

per la qualità della didattica universitaria. Roma, IT.

Puranik, S. (2020). Innovative teaching methods in higher

education. BSSS Journal of Education, 9(1), 67-75.

Rudolph, J., Tan, S., & Tan, S. (2023). ChatGPT: Bullshit

spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher

education?. Journal of Applied Learning and

Teaching, 6(1).

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic

motivations: Classic definitions and new directions.

Contemporary educational psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

Tan, O. S. (2021). Problem-based learning innovation:

Using problems to power learning in the 21st century.

Gale Cengage Learning.

Ujir, H., Salleh, S. F., Marzuki, A. S. W., Hashim, H. F., &

Alias, A. A. (2020). Teaching Workload in 21st

Century Higher Education Learning Setting.

International Journal of Evaluation and Research in

Education, 9(1), 221-227.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

540