Improving the Digital Literacy and Social Participation of Older Adults:

An Inclusive Platform that Fosters Intergenerational Learning

Yusuf Farag, Gopichand Narra, Dharini Balasubramaniam

a

and Kenneth M. Boyd

School of Computer Science, University of St Andrews, North Haugh, St Andrews, U.K.

Keywords:

Accessibility, Aging Population, Autonomy and Active Ageing, Dignity and Equal Opportunities of Senior

Citizens, Digital Literacy, Digital Divide, Intergenerational Learning, Self-Fulfilment and Social Participation,

Social Inclusion, Older Adults, User Interface Design.

Abstract:

In an increasingly digitalised world, many older adults face the choice of improving their digital skills or

risking social isolation and exclusion from essential services. With older adults expected to represent 16% of

the global population by 2050, there is a renewed urgency to improve their digital literacy. Although many

in-person and online technology training initiatives exist, they are often not accessible or poorly optimised

for older adults. Younger adults, who typically form older adults’ support network, may be key to any so-

lution. However, their help typically serves as a temporary fix until a new issue arises, leading to a cycle

of dependency. This pilot study offers insights into the technology experiences of older adults, the ways in

which younger individuals assist them, and how both groups stay connected. We conducted small-scale but

in-depth user studies with older adults, and an online survey of younger adults, to understand how the tech-

nology support process could be improved to promote older adult autonomy and active ageing. Based on our

findings, we propose an age-friendly platform that leverages intergenerational exchanges for a personalised

learning experience that brings together younger and older adults. The final prototype was well received by

participants in the user study. However, further exploration of other aspects of their lives and cultural differ-

ences in intergenerational learning, and larger studies of younger and older individuals are needed to co-create

a solution that helps bridge the global digital divide while enabling older adults to have more fulfilling lives.

1 INTRODUCTION

The world is facing an unprecedented demographic

shift with the number of older adults aged 65+ pre-

dicted to double over the next three decades to 1.6

billion in 2050, and account for 16% of the global

population (United Nations Department of Economic

and Social Affairs, 2023). At the same time, we face

an increasingly digitalised world with services and re-

sources migrating online at a rate accelerated by the

COVID-19 pandemic (United Nations Conference on

Trade and Development, 2021). Since older adults

experience lower rates of technology adoption, accep-

tance, and use, with these levels negatively correlated

with age (Mullins, 2022), there is a growing digital

divide that can cause them to lose access to essential

services such as healthcare, banking, shopping, and

communication channels (Age UK, 2019), while also

increasing the likelihood of social isolation. Accord-

ing to a 2019 Fundamental Rights Survey in the Euro-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5093-0906

pean Union, only one in five individuals aged 75 and

older “at least occasionally engaged in Internet activi-

ties”, compared to 98% of those aged 16 to 29 (United

Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2021).

Consequently, the digital divide is likely to widen as

more services migrate online (Hashimi, 2021).

Older adults often turn to the younger people

in their lives for assistance with technology. Yet,

many younger adults lack the availability, resources,

and training skills to effectively support their el-

ders, resulting in little improvement in the older per-

son’s technology skills and frustration for both sides

(Azevedo and Ponte, 2020; Yuan et al., 2016).

This pilot study, conducted as part of a wider re-

search agenda of reducing the digital exclusion of

older adults, explores two goals: to improve the digi-

tal literacy of older adults to enable continued inde-

pendence, and to increase their social participation

by facilitating digital use with family and peers. We

adopt the definition of digital literacy as “the ability

to use information and communication technologies

Farag, Y., Narra, G., Balasubramaniam, D. and Boyd, K.

Improving the Digital Literacy and Social Participation of Older Adults: An Inclusive Platform that Fosters Intergenerational Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0012623400003699

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2024), pages 47-58

ISBN: 978-989-758-700-9; ISSN: 2184-4984

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

47

to find, evaluate, create, and communicate informa-

tion” (American Library Association, 2023). This re-

search focuses on strategies to reduce the anxieties

older adults may feel when interacting with technol-

ogy, while addressing the motivations and pain points

for both older adults and younger people to whom

they turn for help. Our contributions include a sur-

vey of related work, user studies with older adults, a

survey of younger helpers, prototype user interfaces

reflecting findings, an evaluation of these prototypes,

and insights from the work.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The

background for the work on the digital literacy of

older adults and existing approaches to address this

issue are described in Section 2. An outline of our

methodology to gather insights for potential solutions

is provided in Section 3 followed by the main find-

ings from the user studies in Section 4. The descrip-

tion and evaluation of two prototype solutions are in-

cluded in Sections 5 and 6 with possible limitations

outlined in Section 7. We provide some conclusions

and thoughts on future work in Section 8.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Digital Literacy Barriers for Older

Adults

As well as the traditionally acknowledged physical

and cognitive factors of ageing, older adults also face

significant social barriers such as limited motivation,

lack of support, and anxiety stemming from the fear

of “breaking” the technology they use (Helsper and

Reisdorf, 2013; Friemel, 2016; Bolton, 2010). Stud-

ies have shown the lack of compelling reasons and

interest in digital technologies as a significant factor

in internet non-use (Hashimi, 2021; Helsper and Reis-

dorf, 2013). Moreover, older adults may be discour-

aged from going online due to the unavailability of

and lack of support from family members, including

the belief that their family members are uninterested

in the same technologies. The barrier to digital lit-

eracy is exacerbated by their reliance on others for

training and technical support, physical challenges,

and lack of confidence in their ability to learn to use

the technology (Czaja, 2019; Yuan et al., 2016).

The lack of support and the low technological self-

efficacy of some older adults can further create anxi-

ety around technology due to fears of breaking it and

causing errors (Bolton, 2010; Flynn, 2022; Friemel,

2016). Such concerns stem from the uncertainties of

utilising new technologies with which they have lim-

ited experience (Han and Nam, 2021; Mullins, 2022).

The lack of experience combined with declining mo-

tor skills and the significant cognitive requirements

of trial-and-error learning can cause older adults to

spend more time on tasks (Brajnik and Giachin, 2014;

Yoo, 2021). As a result, older adults are more nega-

tively affected by mistakes and experience a stronger

psychological effect than younger users, leading to in-

creased anxiety over potential negative outcomes due

to operational errors (Brajnik and Giachin, 2014; Tsai

et al., 2017; Yoo, 2021). These fears not only stifle

the exploration of new technologies but also decrease

their motivation to learn and willingness to use them

(Atkinson et al., 2016; Brajnik and Giachin, 2014;

Patr

´

ıcio and Os

´

orio, 2011).

2.2 Digital Literacy Motivators for

Older Adults

Older adults are motivated to embrace digital tech-

nologies (Han and Nam, 2021) and more inclined to

learn and use them with higher levels of satisfaction if

these technologies are perceived as valuable and easy

to operate (Tsai et al., 2017; Tyler et al., 2020). In

addition, any benefits from such technologies must

relate to the older adults’ personal and social needs

(Mart

´

ınez-Alcal

´

a et al., 2018). Another key moti-

vator, self-efficacy through learning, has been found

to improve perceived usefulness and ease of use by

raising the confidence of older adults in using digi-

tal technology and reducing their technology-related

anxiety (Han and Nam, 2021; Tyler et al., 2020).

Older adults are more likely to wish to learn specific

tasks and require content that is designed with their

learning styles, interests and expectations in mind, in-

stead of generalised learning (Mart

´

ınez-Alcal

´

a et al.,

2018; Mitzner et al., 2008). Studies have shown

that tailoring a learning activity to the preferences of

older adults can increase their motivation to partici-

pate (Hashimi, 2021; Tyler et al., 2020).

Measures to reduce cognitive load and improve

system support can enhance error prevention and

recovery, which improves the learning experience.

Strategies such as training at an accessible pace,

step-by-step instructions, repetition of content, visual

aids, and digitalised note-taking can also address var-

ious age-related challenges including poor memory

(Mullins, 2022). The provision of quick, efficient, and

accessible pathways to system support can help users

avoid making errors when interacting with digital

technologies and reduce their annoyance from search-

ing for advice to deal with their difficulties (Tsai et al.,

2017; Tyler et al., 2020). In addition to encouraging

them to engage with digital technologies, a friendly

space for trial and error serves as an important fa-

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

48

cilitator for the learning experience of older adults

(Barnard et al., 2013; Tsai et al., 2017). Likewise,

user guidance has a direct impact on the perception of

usefulness and learnability and an indirect impact on

end-user satisfaction (Tsai et al., 2017).

Studies have shown that social support plays a

significant role in improving the digital literacy of

older adults (Hashimi, 2021). Ongoing support from

trusted sources is essential in enabling older adults to

overcome their anxieties and challenges, build skills,

and develop confidence in the ever-changing land-

scape of digital technologies (Bolton, 2010). This

leads older adults to perceive the usefulness and ease

of use of digital technologies (Han and Nam, 2021).

In particular, older adults value social connection and

are intrinsically motivated to adopt and regularly use

digital technologies when they are personally rele-

vant, useful and supported by members of the older

adult’s family (Mart

´

ınez-Alcal

´

a et al., 2018; Tyler

et al., 2020).

2.3 Leveraging Intergenerational

Learning

Family members are often the preferred source of

support with digital technology among older adults,

with children influencing technology adoption and

use (Flynn, 2022; Friemel, 2016; Fausset et al., 2013;

Tsai et al., 2017). The intergenerational approach, in-

volving younger family members as tutors, can pro-

vide effective support through its informal nature, ac-

cessibility, and understanding of any special needs

(Atkinson et al., 2016; Flynn, 2022; Tsai et al., 2017).

By creating a supportive learning atmosphere and ad-

dressing technical challenges, the younger generation

plays a crucial role in alleviating demotivating emo-

tions like anxiety and confusion. Their encourage-

ment also sparks a newfound interest in digital tech-

nologies among older adults, while fostering stronger

familial bonds (Hashimi, 2021).

As well as increasing the self-esteem of older

adults and their trust in digital technologies, the

reinforced social connection between younger and

older family members can mitigate physical ab-

sence, promote independence and autonomy, and en-

hance family communication regardless of geograph-

ical distance to combat loneliness and social isola-

tion (Azevedo and Ponte, 2020; Flynn, 2022). While

younger adults appreciate the value of social connec-

tion and consider it important to assist older family

members with their technical issues (Flynn, 2022),

they may also feel social pressures to do so (Azevedo

and Ponte, 2020). The intergenerational approach

offers reciprocal learning opportunities for younger

adults who develop increased patience and under-

standing when teaching older relatives the digital

technologies they take for granted (Flynn, 2022). This

interaction strengthens family relations, reduces bar-

riers, and breaks “negative stereotypes between gen-

erations” (Hashimi, 2021). In addition, these younger

adults gain improved leadership abilities, self-esteem

and confidence (Hashimi, 2021).

However, the intergenerational approach can be

inhibited by limits to the availability of family mem-

bers and their teaching abilities. One of the great-

est barriers older adults face is family members be-

ing busy with their work, families, and social lives.

While, along with geographical distance, this can

make communication difficult (Yuan et al., 2016),

family members are still mostly supportive whenever

possible (Tsai et al., 2017). Increased digital liter-

acy with Internet usage could offer more opportuni-

ties to make communication easier and more flexible

for older and younger family members (Azevedo and

Ponte, 2020).

Even if a younger family member has the tech-

nical experience and readiness to help, they may not

have the required teaching skills (Azevedo and Ponte,

2020). Without an understanding of older adults’

slower learning pace of due to the physical and cogni-

tive limitations of ageing, younger adults may lack the

patience to teach them (Azevedo and Ponte, 2020).

This can lead to a situation where younger people

demonstrate solutions too quickly to be useful. The

quick fix is for the younger person to simply per-

form the task themselves rather than persisting with

the learning process (Renaud and van Biljon, 2008).

This not only discourages older adults from improv-

ing their digital skills but can also increase confu-

sion and intimidation by such technologies, leading

to frustrations for both older adults and their support

network due to the older adults’ ongoing dependence

on their younger peers for completing tasks (Flynn,

2022). Only when these limitations are addressed

can intergenerational learning offer new opportuni-

ties for older adults to improve their digital literacy,

while bringing them and their younger family mem-

bers closer together.

2.4 Evaluation of Existing Solutions

Older adults can now access a range of online ser-

vices to improve their digital literacy. Platforms

such as Learn My Way

1

, TechBoomers

2

, and Google’s

1

https://www.learnmyway.com/

2

https://techboomers.com/

Improving the Digital Literacy and Social Participation of Older Adults: An Inclusive Platform that Fosters Intergenerational Learning

49

Applied Digital Skills

3

offer online help guides and

courses for older adults who are struggling with tech-

nology, or want to expand their understanding of it.

There is also preliminary research into an age-friendly

online learning system within the context of informal

family learning (Vaswani et al., 2023), which moti-

vates this work.

In some cases, an easy-to-use interface, for exam-

ple, with information clearly laid out or requiring a

few simple steps to complete a task, with a single

search bar and step-by-step guides may be sufficient

for older adults to learn about the digital technol-

ogy they require, especially when they are accessed

through a desktop or laptop. However, with the rising

adoption of touchscreen devices among older adults

(Faverio, 2022), many may struggle to use platforms

that are not optimised for touch interfaces. For in-

stance, text and interactive elements such as buttons

and links may appear smaller and harder to read or

tap on (Kane, 2019), and menus may be hidden be-

hind icons that are unfamiliar.

Moreover, these platforms often have a separate

user registration process requiring the creation of an

additional account, the details of which need to be re-

membered, offer limited error prevention and recov-

ery measures, and lack system support such as prod-

uct tours and help on every page. Given that many

older adults tend to experience a slowdown of cog-

nitive processes as they age (Caprani et al., 2012),

these limitations can make completing tasks on such

platforms more stressful and challenging. Since older

adults are particularly sensitive to making errors, such

experiences may increase their apprehension and de-

crease their motivation to learn and use such plat-

forms (Brajnik and Giachin, 2014; Yoo, 2021).

There are usually limited options in existing sys-

tems to personalise the learning process based on

one’s abilities and impairments (such as vision lev-

els or motor skills), and their goals and interests. This

can reduce the accessibility, perceived usefulness, and

ease of use of such platforms, which are pivotal fac-

tors for engagement (Han and Nam, 2021). In addi-

tion, the lack of note-taking features (other than the

option to print guides) and an isolated training envi-

ronment, along with memory issues, may hinder the

ability of older adults to retain information, while also

feeling unsupported. Existing platforms frequently

fail to consider the perspectives of the younger fam-

ily members and acquaintances, who provide support,

by either involving them in the training process or of-

fering them guidance on how to help the older adults

with their technology-related enquiries. Since older

3

https://applieddigitalskills.withgoogle.com/s/en-

uk/home

adults frequently mention family members as their

preferred source of digital technology support (Flynn,

2022; Friemel, 2016; Mitzner et al., 2008; Tsai et al.,

2017), this is a missed opportunity for them to play

a significant role in creating a supportive learning en-

vironment, especially to address feelings of anxiety

or confusion during the older adult’s training process,

and to be the stimulus for engaging with learning.

3 METHODOLOGY

Our approach to improving the digital literacy of older

adults involves both older adults and their support net-

work, who are usually the younger people in their

lives. Therefore, user studies with older adults (more

likely to be available in person) and an online sur-

vey of younger individuals (typically with more time

commitments) were conducted to better understand

how intergenerational learning can be leveraged to in-

crease digital literacy among older adults and foster

social participation between the generations. Ethics

approval from the authors’ institution was obtained

prior to this work.

Thematic coding of the responses from both

groups of users was conducted using Work Activity

Affinity Diagrams (WAADs), which is a hierarchical

bottom-up technique that places similar feedback to-

gether to highlight common or shared themes (Hart-

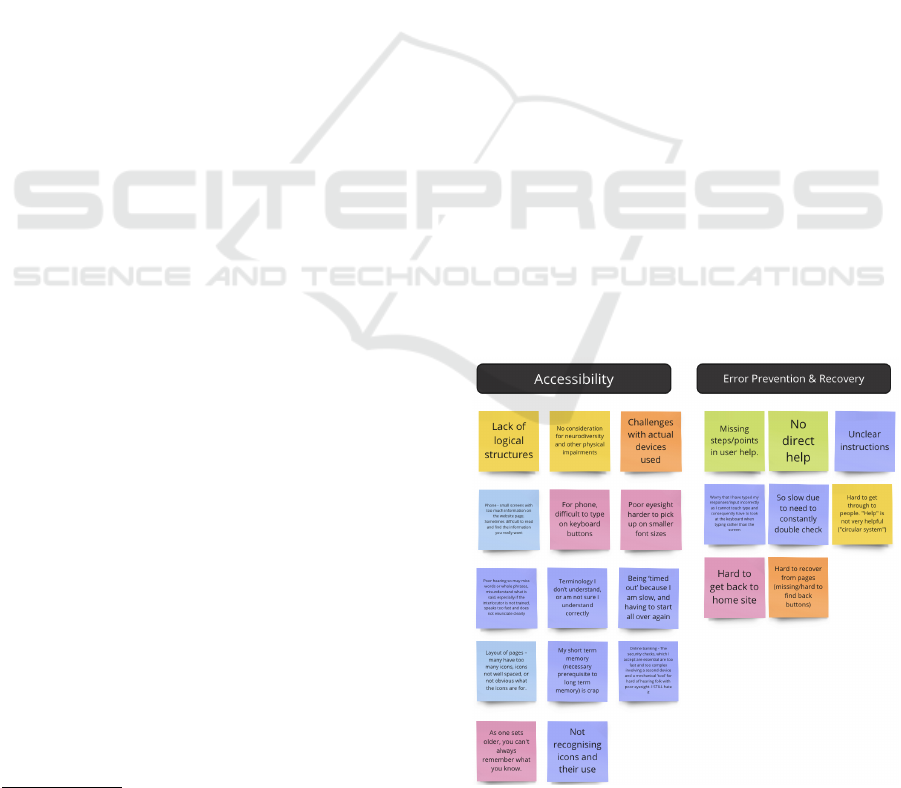

son and Pyla, 2018). As shown in Figure 1, this in-

cluded key strategies, pain points, and areas of im-

provement within the technology support process for

both younger and older adults. The results were then

Figure 1: Sample Older Adult Interview WAAD for their

Key Digital Technology Challenges and Frustrations.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

50

used to develop prototypes of the EldersOnline plat-

form discussed in Section 5.

3.1 User Studies with Older Adults

6 participants (4 women and 2 men) aged 70 to 79

were recruited from the UK through snowball sam-

pling and split across 3 rounds of in-depth user study

sessions. For the first part of the study, in-person

semi-structured interviews were carried out to explore

the motivations and challenges for older adults us-

ing digital technology, their preferred means of sup-

port with technology issues, and ways to increase

their social connectedness with younger generations.

The second part involved a think-aloud session where

users completed tasks on a prototype tablet appli-

cation (produced as a high-fidelity on Figma

4

) and

another semi-structured interview to explore partici-

pants’ experience using the prototype, with the pro-

totype being updated after each round of feedback as

part of an iterative user-centred design process.

3.2 Survey of Younger Individuals

An anonymous online survey of younger adults be-

tween the ages of 18 and 64 was conducted to gather

feedback on the methods used, motivations, chal-

lenges, and areas of improvement in supporting older

adults, as well as ways to increase engagement be-

tween them and older adults. Participants were re-

cruited through social media and snowball sampling.

In total, 50 responses were collected with 39 aged 18-

24, 7 aged 25-34, 2 aged 45-54, and 2 aged 55-64

(Figure 2). 70% of the respondents were comfortable

with using and teaching others to use information and

communication technology (ICT) devices and online

services, 26% were comfortable using them, and 4%

required assistance with them.

4 DISCUSSION OF INITIAL

FINDINGS

In this section, we outline the findings from our stud-

ies with older adults and their younger helpers.

4.1 Findings from the First User Study

with Older Adults

Our participants appeared more digitally literate than

typical in literature from the past decade (Friemel,

4

https://www.figma.com/

Figure 2: Survey Respondent Age Demographics.

2016; Czaja, 2019; Yazdani-Darki et al., 2020;

Mart

´

ınez-Alcal

´

a et al., 2018), with all 6 using the

Internet daily. All participants primarily use a lap-

top/desktop, and own a tablet and smartphone, thus

having access to a range of devices. The following

themes were identified from their experience with dif-

ferent online interfaces:

• Accessibility. 5 participants highlighted accessi-

bility challenges, including limited consideration

for neurodiversity and physical impairments, poor

content layouts, and unfamiliar terminology and

icons. Phones, due to their smaller display, posed

usability issues for 3 participants. Cognitive de-

clines mentioned by 2 participants led to difficulty

with tasks timing out and having to restart due to

the time taken to complete them.

• Error Prevention and Recovery. A recurring

theme among 5 participants was the lack of er-

ror prevention and recovery methods: inadequate

user help, including unclear instructions and miss-

ing steps (3 participants), and challenges with re-

covery due to missing or hard-to-find “back but-

tons” that caused delays and frustrations (2). Ef-

fective help and user control are needed to allevi-

ate the impact of these issues (Nielsen, 2020).

• Online Security. 5 participants had concerns

about online security, including scams and hack-

ing. 2 mentioned worries about privacy due to

weak protections and data leaks. Text/email ver-

ification delays caused access concerns for one

participant. Overall, participants shared a cau-

tious and vigilant approach to online navigation.

• Fear of Making Mistakes. Limited digital famil-

iarity led 2 participants to express fear of damag-

ing or permanently altering the digital technolo-

gies they use, aligning with literature (Bolton,

2010; Flynn, 2022; Friemel, 2016; Hashimi,

2021; Mullins, 2022; Tsai et al., 2017).

Improving the Digital Literacy and Social Participation of Older Adults: An Inclusive Platform that Fosters Intergenerational Learning

51

Participants mentioned the following as the most

appealing aspects of different online interfaces:

• Good Design and Usability. Participants valued

well-designed and intuitive interfaces. This in-

cluded a clear structure, identifiable “home” op-

tions, and a streamlined process.

• Personalisation. Participants emphasised the im-

portance of providing plenty of personalisation

options, with customisable font sizes and the abil-

ity to remove distracting elements to enhance in-

formation focus.

The following themes were highlighted in ad-

dressing technology-related struggles:

• Frequency of Issues. In general, participants do

not struggle with major issues often, with the fre-

quency ranging from 1-2 issues weekly to once or

twice a year.

• Sources of Support. Participants predominantly

turn to four support channels for technology as-

sistance: family, friends, customer support, and

video tutorials. Notably, grandchildren play a

heightened role, with some participants preferring

them over their children due to their increased

availability. “Tech-savvy” friends and video tuto-

rials are also highlighted as important resources.

• Increasing Awareness. For 4 participants, a re-

curring theme was raising awareness about their

physical and cognitive challenges, gaps in their

knowledge, and learning styles within their sup-

port network. Participants emphasised the need

for empathy, supported practice, opportunities to

practise in real life without feeling inadequate,

and more relatable help facilities. These answers

highlight the importance of a learning environ-

ment that offers accessible, empathetic help and

regular practice.

On engagement with younger family members,

the resulting feedback showed variances as indicated

below:

• Bonding Through Technology Support. Partic-

ipant views varied on whether receiving technol-

ogy support from younger family members would

strengthen their relationships. 3 participants ex-

pressed concerns about feeling burdensome or be-

ing mocked, and noted that their slower learn-

ing pace could reduce the willingness of younger

members to assist. Others saw it as a means

of mutual support that broke traditional norms.

While 2 participants acknowledged the potential

for enhanced connections, they pointed out that

the busy schedules of their younger family mem-

bers might affect the feasibility of such support.

4.2 Findings from Online Survey of

Younger Adults

The following insights were gathered regarding sup-

porting older adults with their technology-related is-

sues:

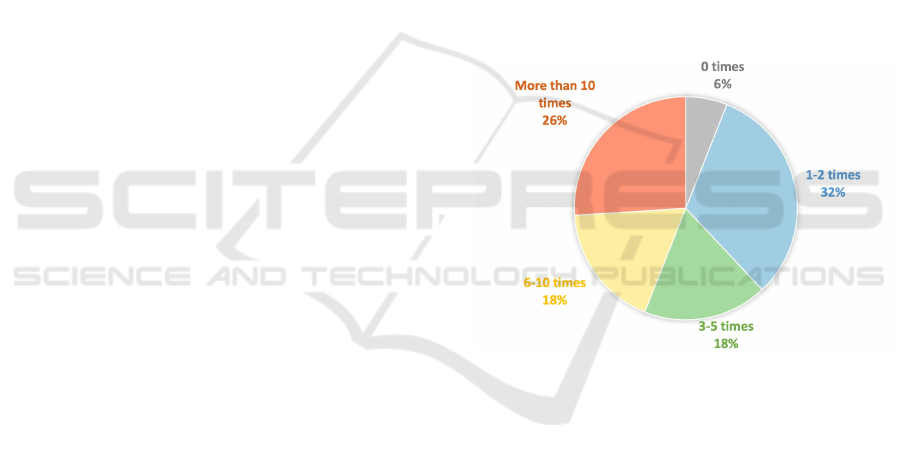

• Supporting Older Adults. 94% of respondents

had helped older adults around them with their

technology issues in the previous six months, with

26% doing so more than ten times (Figure 3). 46

respondents were intrinsically motivated to help

because they: wanted to enhance the lives of

their older peers, were approached for assistance,

wanted to show their appreciation, or felt obli-

gated to do so. 3 mentioned how doing so pre-

vents them from being asked about issues “again

and again”. 2 respondents shared the increased

satisfaction and self-confidence from helping, and

another 2 remarked on how it improved family

connections.

Figure 3: Frequency of Technology Support within the Last

6 Months.

• Common Frustrations. There were frustrations

with explaining basic concepts (29 individuals),

repeating solutions (9), and the time-consuming

nature of supporting older adults with technology

issues (2). Challenges also arose from the reluc-

tance of older adults to learn (7) and their con-

cerns about scams and privacy (2).

• Enhancing the Support Process. Respondents

suggested clear and understandable tutorials (10

individuals), a platform for any initial queries (7),

and screen-recording facilities for demonstrations

(9) to enhance support. 7 respondents also em-

phasised the importance of having more patience

when teaching older adults.

• Connecting with Older Adults. 72% of respon-

dents contacted the older adults in their lives at

least once a month (Figure 4). Among the respon-

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

52

dents, 20 enjoyed hearing about life experiences

and advice from their older family members, 16

wanted to receive updates about their health and

daily life, 4 on their shared hobbies/interests and

general chat, and 2 respondents liked to explore

the views of older adults on current events.

Figure 4: Frequency of Contact with Older Adults.

• More Intergenerational Interactions. While 22

respondents were unsure how to increase engage-

ment with their elders, 11 proposed more frequent

interactions based on shared interests. 6 respon-

dents mentioned the idea of reminders, 4 sug-

gested encouraging older adults to use social me-

dia to improve communications, and 3 suggested

the ability to exchange pictures and memories.

One respondent expressed the wish to let older

adults know they are in their family’s thoughts and

to keep them updated on their lives.

5 THE EldersOnline PLATFORM

We developed prototypes of a platform called Elder-

sOnline to implement the insights gained from the ini-

tial user studies, which were organised and prioritised

using a MoSCoW Analysis in the order of “Must”,

“Should”, “Can”, and “Won’t” have requirements.

This included features that facilitated and stored inter-

generational exchanges through an accessible user in-

terface as well as error prevention/recovery measures

to reduce barriers to using technology.

Before the proposed interface solution was devel-

oped, a consistent visual design and style guide was

established through an extensive literature review for

the system’s visual elements, including:

• Well-contrasted colour options of magenta or pur-

ple (alongside light/dark modes) with distinct

hues (Farage et al., 2012) and a minimum contrast

ratio of 4:5:1 (Anagnostou, 2020).

• The use of Helvetica typeface (Farage et al.,

2012), adjustable font sizes starting at 16 pixels

(Campbell, 2015; Universal Design, 2020), and

the use of plain language for maximum readabil-

ity (Guimar

˜

aEs et al., 2022).

• Icons with descriptive text (Farage et al., 2012),

minimum 15.9mm x 9.0mm button size, and spac-

ing of interface elements (Gao and Sun, 2015).

• Simple and uncluttered interface to make the con-

tent clear and easy to find (Guimar

˜

aEs et al., 2022;

Universal Design, 2020).

• Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

Level AAA compliance (Who Can Use, 2023).

5.1 EldersOnline Features

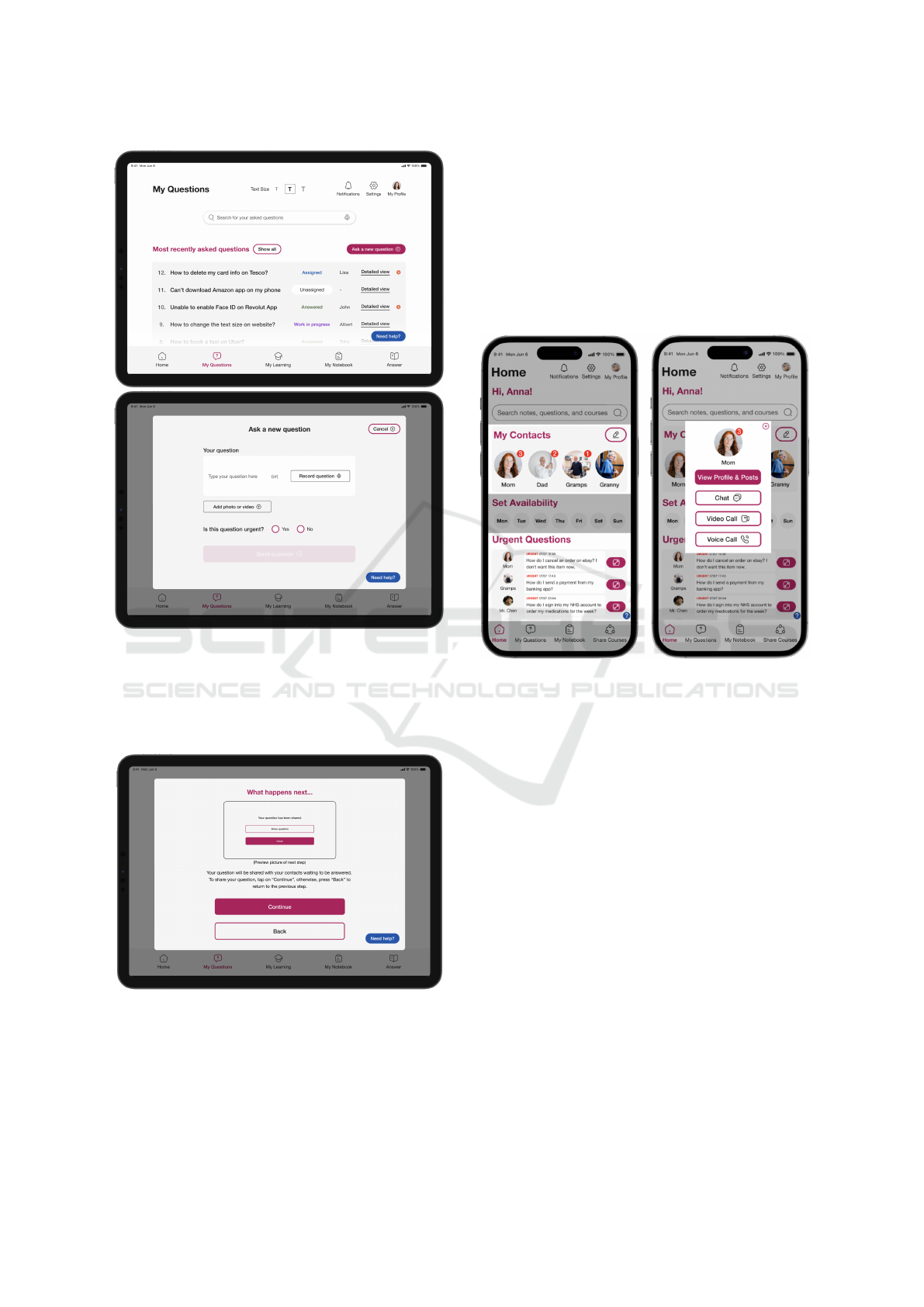

Initially, lower-fidelity prototypes were developed

based on the survey of existing work. Two high-

fidelity Figma prototypes were then created and re-

fined through user studies to form the EldersOnline

platform. This included a tablet application to support

the digital literacy and social participation of older

adults and a smartphone version for younger adults

to better assist and engage with their older peers. The

interface for older adults includes the following fea-

tures:

• Passwordless Login/Registration. The elimina-

tion of passwords for a more streamlined authen-

tication process that addresses the issue of forgot-

ten passwords due to poor memory. This miti-

gates any feelings of confusion, frustration, and

decreased confidence that might discourage use.

• Personalisation. To maximise accessibility for a

diverse user demographic, personalisation options

to change the text size, system theme, and back-

ground colour were implemented.

• Question Sharing. Older users can search or

view all their existing technology-related ques-

tions and resolution statuses, or ask a new one

to their younger contacts with text, audio, and

photo/video input options (Figure 5).

• Question Answering. Intergenerational ex-

changes are facilitated by enabling older adults to

view and respond to questions posted by younger

adults. As well as encouraging older adults to en-

gage more with the platform, this allows younger

adults to draw on a lifetime of experiences and

wisdom. At the same time, this feature can allevi-

ate an older adult’s feeling of being burdensome

to their younger peers by giving them a chance to

offer meaningful contributions, all while improv-

ing intergenerational social participation.

Improving the Digital Literacy and Social Participation of Older Adults: An Inclusive Platform that Fosters Intergenerational Learning

53

Figure 5: Question Sharing Feature.

• Action Preview. Users are shown what happens

next before proceeding with their inputs. This was

implemented for various creation actions to im-

prove error prevention and recovery (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Action Preview Feature.

• Online Learning. Users can search for and view

online tutorials/guides (including those recom-

mended by their contacts) with options to add an-

notations and save specific tutorials/guides to their

digital notebook, which is a place for them to add

new notes or access any previously saved ones.

The smartphone version of EldersOnline has simi-

lar design and functional features as the tablet version,

but it differs in the following features to better cater

to the needs of the younger user base.

• Offering Support. Users can assist their older

peers with their technology issues by accessing

the older contact’s posts or getting in touch di-

rectly by voice/video call or chat (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Ways to Identify and Support Older Adult Tech-

nology Issues.

• Support Guidance. Both the ”Accessibility” and

”Support Tips” sections raise awareness of the

challenges faced by older adults, while guiding

younger users to provide tailored support for op-

timal learning outcomes (Figure 8).

• Setting Availability. Given the busy schedules of

younger adults and the concerns of older adults

about making requests of them when they are

busy, EldersOnline allows users to set the times

when they are free to help with technology-related

questions, alleviating the concerns of older adults.

• Check-In Reminders. Users can set reminders to

encourage more frequent interactions.

• Share Courses. A place for safe and age-friendly

solutions that younger users could share with

their older peers immediately with minimal ef-

fort. This is also an opportunity for them to en-

courage their older peers to grasp basic technol-

ogy concepts/knowledge that could improve their

long-term digital literacy.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

54

Figure 8: Tips for Helping Older Adults.

6 EVALUATION OF EldersOnline

PLATFORM

The in-person evaluation of the EldersOnline high-

fidelity tablet prototype for older adults consisted of

two stages: a think-aloud product testing session and

a post-session semi-structured interview about their

experiences of using it. We also include a comparison

of EldersOnline with existing solutions mentioned in

Section 2.4.

6.1 Think-Aloud Evaluations

Think-alouds require participants to continuously ver-

balise their thought process as they perform a series

of pre-determined tasks (Birch and Whitehead, 2020).

This protocol was specifically chosen for its value in

identifying usability problems (Fan et al., 2020). Par-

ticipants were given an iPad with the prototype loaded

for a more realistic experience for this session. Given

the iterative nature of our design process, we began

our first think-aloud round with three tasks and grad-

ually extended them with additional features and up-

dates. We also included metrics such as a 1-5 ease of

use rating, task success, task time, and the number of

errors to better understand how easy or hard it was to

use our prototype for each task.

In general, participants found the interface easy

and straightforward to use, especially once they were

familiar with it. They frequently used a trial-and-

error approach to navigate around the platform and

its functions. There was constructive feedback on

the size, colour, and placement of buttons, the op-

tion to directly get in touch with a specific contact to

pose a question instead of “troubling” or “bombard-

ing” everyone, and the wording of different interface

elements, which highlight the ongoing need to elimi-

nate “technical jargon” that many take for granted and

which can prove confusing for older users.

6.2 Post-Session Interviews

Participants appreciated the accessibility, password-

less login, and error prevention/recovery measures

within the prototype. They praised the simple, clear

layout with contrast and text-resizing options. They

noted that being able to see what happens next before

initiating an action can be “rescuing”, prevent the per-

ception of causing serious damage, and offer a simple

and well-delineated escape route for people, making

it easy to recover from errors.

At the same time, they recommended enhancing

the clarity and navigation of certain pages by simpli-

fying them. They emphasised the need for a system

guide/tutorial and suggested rewording certain inter-

face elements to be more understandable. Overall,

our prototype garnered a mixed response from par-

ticipants. Two expressed intent to use, one saw value

if accessible on their phone, and three showed disin-

terest. When asked about the reasons for their inter-

est, participants mentioned the advantages of learning

to access specific digital technologies and online ser-

vices. Notably, a participant highlighted the potential

safety and reassurance this prototype offers to older

users compared to searching on Google. Conversely,

reasons for non-use included favouring existing social

connections and using Google for queries.

6.3 Comparison with Existing Solutions

EldersOnline shares a number of key features with ex-

isting solutions, such as having an age-friendly inter-

face, step-by-step tutorials that are printable, course

recommendations, and a single search function.

Building on existing work and making use of

the insights gained from older adults and younger

helpers, EldersOnline offers its users a more acces-

sible authentication process, enhanced error preven-

tion measures such as action previews, touchscreen

optimisation, a more personalised learning experi-

ence, including customisable interface elements and

digitalised note-taking, and greater involvement from

older adults’ support network, including sharing ques-

tions, knowledge and resources, and facilitating inter-

actions.

At the same time, as a prototype solution to the

Improving the Digital Literacy and Social Participation of Older Adults: An Inclusive Platform that Fosters Intergenerational Learning

55

problems identified earlier, EldersOnline focuses on

touchscreen use and currently lacks an onboarding

process and desktop optimisation found in some exist-

ing solutions. This can impact the experience of some

users, especially those who become anxious with new

technologies or primarily use a computer to access the

internet. Adding these features is part of the future

work planned for EldersOnline.

7 THREATS TO VALIDITY

While even a few older participants can provide valu-

able insights in this context (Budiu, 2021), a key lim-

itation of this preliminary investigation is the small

sample size in terms of the diversity of age, abilities,

and cultures, as all were recruited locally and may not

be fully representative of this demographic. In partic-

ular, there is a lack of input from participants over the

age of 79, which combined with the fact that digital

engagement is negatively correlated to age (Mullins,

2022), can lead to a gap in this research.

8 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Existing work in this area emphasises the develop-

ment of accessible experiences. However, there has

been limited consideration of the potential of an older

adult’s immediate support network to encourage a

dignified two-way exchange of knowledge in support

of active ageing and stronger intergenerational bonds.

Key findings of this pilot study include the im-

portance of designing interfaces for older adults that

promote accessibility, customisability, simplicity, er-

ror prevention and recovery, confidence in use, and

trusted support. Effective intergenerational support

is vital, and requires a greater awareness of the chal-

lenges of ageing and empathy for older adults’ learn-

ing style and their concerns among their support net-

works, as well as learning platforms that provide

mechanisms to reduce teaching frustrations. Such

measures can allow older adults to develop greater

self-reliance and break the cycle of dependency on

their younger peers.

At the same time, there is an opportunity for older

adults to further contribute to the intergenerational

learning process by sharing their experiences with

their younger peers. As well as encouraging two-way

engagement, this can lead to improved social partici-

pation and reduce the risks of social isolation.

The study led to the development of two pro-

totypes that attempted to implement these findings.

While the evaluation yielded mixed responses, the

prototypes show potential in addressing the issue.

User studies indicate that the “action preview” con-

cept could be applied to destructive actions like

“delete” across different platforms to mitigate the

negative impact of errors. The proposed solutions can

be extended to support general enquiries older adults

may have about their daily lives. Expanding its usage

scenarios may encourage older adults to use Elder-

sOnline to maintain their independence as it is able to

meet more of their needs.

There are many avenues for further research. The

prototypes need to be evaluated with younger adults

to determine their efficacy from that perspective. A

popular sentiment among older participants was that

EldersOnline could not fully replace face-to-face in-

teractions. Hence, it may be less useful to users with

younger families close by, highlighting the need to

facilitate a greater variety of interactions beyond a

’question and answer’ experience. Likewise, this so-

lution may not fully apply to older adults without

younger people who can help. Additional research is

required to determine alternative ways to engage with

them and support their digital literacy.

Another area for further research is how intergen-

erational learning can be applied across different cul-

tures, since each may approach such exchanges differ-

ently. Support mechanisms for digital literacy need

to be re-evaluated regularly to take into account the

rapidly changing technology landscape. By consider-

ing the above factors, platforms such as EldersOnline

can inspire innovative and impactful solutions that ef-

fectively bridge the digital divide, foster social par-

ticipation through stronger intergenerational ties, and

enhance the overall quality of life for older adults.

REFERENCES

Age UK (2019). Later life in the united kingdom

2019. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/

age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/

later life uk factsheet.pdf.

American Library Association (2023). Digital literacy.

https://literacy.ala.org/digital-literacy/.

Anagnostou, J. (2020). Ux study: Designing for older

people. https://uxplanet.org/ux-study-designing-for-

older-people-6c67575d9c2f.

Atkinson, K., Barnes, J., Albee, J., Anttila, P., Haataja, J.,

Nanavati, K., Steelman, K., and Wallace, C. (2016).

Breaking barriers to digital literacy: an intergenera-

tional social-cognitive approach. In Proceedings of

the 18th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference

on Computers and Accessibility, pages 239–244.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

56

Azevedo, C. and Ponte, C. (2020). Intergenerational sol-

idarity or intergenerational gap? how elderly people

experience ict within their family context. Observato-

rio (OBS*), 14(3):16–35.

Barnard, Y., Bradley, M. D., Hodgson, F., and Lloyd,

A. D. (2013). Learning to use new technologies by

older adults: Perceived difficulties, experimentation

behaviour and usability. Computers in human behav-

ior, 29(4):1715–1724.

Birch, P. D. and Whitehead, A. E. (2020). Investigating the

comparative suitability of traditional and task-specific

think aloud training. Perceptual and Motor Skills,

127(1):202–224.

Bolton, M. (2010). Older people, technology and commu-

nity: the potential of technology to help older people

renew or develop social contacts and to actively en-

gage in their communities. Independent Age.

Brajnik, G. and Giachin, C. (2014). Using sketches and

storyboards to assess impact of age difference in user

experience. International journal of human-computer

studies, 72(6):552–566.

Budiu, R. (2021). Why 5 participants are okay in a qualita-

tive study, but not in a quantitative one. https://www.

nngroup.com/articles/5-test-users-qual-quant/.

Campbell, O. (2015). Designing for the elderly:

Ways older people use digital technology differ-

ently. https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2015/02/

designing-digital-technology-for-the-elderly/.

Caprani, N., O’Connor, N., and Gurrin, C. (2012). Touch

screens for the older user. In Assistive Technologies,

chapter 5, pages 95–118. IntechOpen.

Czaja, S. J. (2019). Usability of technology for older adults:

Where are we and where do we need to be. Journal of

usability studies, 14(2):61–64.

Fan, M., Li, Y., and Truong, K. N. (2020). Automatic de-

tection of usability problem encounters in think-aloud

sessions. ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent

Systems (TiiS), 10(2):1–24.

Farage, M. A., Miller, K. W., Ajayi, F., and Hutchins,

D. (2012). Design principles to accommodate older

adults. Global journal of health science, 4(2):2.

Fausset, C. B., Harley, L., Farmer, S., and Fain, B. (2013).

Older adults’ perceptions and use of technology: A

novel approach. In Universal Access in Human-

Computer Interaction. User and Context Diversity:

7th International Conference, UAHCI 2013, Held as

Part of HCI International 2013, Las Vegas, NV, USA,

July 21-26, 2013, Proceedings, Part II 7, pages 51–58.

Springer.

Faverio, M. (2022). Share of those 65 and older

who are tech users has grown in the past

decade. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-

reads/2022/01/13/share-of-those-65-and-older-

who-are-tech-users-has-grown-in-the-past-decade/.

Flynn, S. (2022). Bridging the age-based digital divide:

An intergenerational exchange during the first covid-

19 pandemic lockdown period in ireland. Journal of

Intergenerational Relationships, 20(2):135–149.

Friemel, T. N. (2016). The digital divide has grown old:

Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New

media & society, 18(2):313–331.

Gao, Q. and Sun, Q. (2015). Examining the usability of

touch screen gestures for older and younger adults.

Human factors, 57(5):835–863.

Guimar

˜

aEs, L., Martins, N., Pereira, L., Penedos-Santiago,

E., and Brand

˜

aO, D. (2022). Interface design guide-

lines for low literature users: a literature review. In

Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference

on Education and E-Learning, pages 29–35.

Han, S. and Nam, S. I. (2021). Creating supportive environ-

ments and enhancing personal perception to bridge the

digital divide among older adults. Educational Geron-

tology, 47(8):339–352.

Hartson, R. and Pyla, P. S. (2018). The UX book: Agile UX

design for a quality user experience. Morgan Kauf-

mann.

Hashimi, S. A. (2021). The role of empowering mature

and older people’s usage of digital media in enhancing

intergenerational communication and family relation-

ships in bahrain. Gerontechnology, 20(2).

Helsper, E. J. and Reisdorf, B. C. (2013). A quantitative

examination of explanations for reasons for internet

nonuse. Cyberpsychology, behavior, and social net-

working, 16(2):94–99.

Kane, L. (2019). Usability for seniors: Challenges and

changes. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-

for-senior-citizens/.

Mart

´

ınez-Alcal

´

a, C. I., Rosales-Lagarde, A., Alonso-

Lavernia, M. d. l.

´

A., Ram

´

ırez-Salvador, J.

´

A.,

Jim

´

enez-Rodr

´

ıguez, B., Cepeda-Rebollar, R. M.,

L

´

opez-Noguerola, J. S., Bautista-D

´

ıaz, M. L., and

Agis-Ju

´

arez, R. A. (2018). Digital inclusion in

older adults: A comparison between face-to-face and

blended digital literacy workshops. Frontiers in ICT,

5:21.

Mitzner, T., Fausset, C., Boron, J., Adams, A., Dijkstra,

K., Lee, C., Rogers, W., and Fisk, A. (2008). Older

adults’ training preferences for learning to use tech-

nology. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Er-

gonomics Society, 52:2047–2051.

Mullins, E. (2022). Building digital liter-

acy among older adults: Best practices.

https://www.socialconnectedness.org/wp-

content/uploads/2022/11/Emily-Final-Report-

Building-Digital-Literacy-Among-Older-Adults.pdf.

Nielsen, J. (2020). 10 usability heuristics for user inter-

face design. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-

usability-heuristics.

Patr

´

ıcio, M. R. and Os

´

orio, A. (2011). Lifelong learning,

intergenerational relationships and ict: perceptions of

children and older adults. In Elderly, Education, Inter-

generational Relationships and Social Development.

Proceedings of 2nd Conference of ELOA, pages 224–

232. ELOA.

Renaud, K. and van Biljon, J. (2008). Predicting technology

acceptance and adoption by the elderly: a qualitative

study. In Proceedings of the 2008 Annual Research

Conference of the South African Institute of Computer

Improving the Digital Literacy and Social Participation of Older Adults: An Inclusive Platform that Fosters Intergenerational Learning

57

Scientists and Information Technologists on IT Re-

search in Developing Countries: Riding the Wave of

Technology, SAICSIT ’08, pages 210–219. Associa-

tion for Computing Machinery.

Tsai, T.-H., Chang, H.-T., Chen, Y.-J., and Chang, Y.-S.

(2017). Determinants of user acceptance of a specific

social platform for older adults: An empirical exami-

nation of user interface characteristics and behavioral

intention. PLOS ONE, 12(8):e0180102.

Tyler, M., De George-Walker, L., and Simic, V. (2020). Mo-

tivation matters: Older adults and information com-

munication technologies. Studies in the Education of

Adults, 52(2):175–194.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Devel-

opment (2021). How covid-19 triggered

the digital and e-commerce turning point.

https://unctad.org/news/how-covid-19-triggered-

digital-and-e-commerce-turning-point.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social

Affairs (2023). World social report 2023: Leav-

ing no one behind in an ageing world. https:

//desapublications.un.org/publications/world-social-

report-2023-leaving-no-one-behind-ageing-world.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

(2021). Mainstreaming ageing - revisited.

https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/ECE-

WG.1-39-PB27 0.pdf.

Universal Design (2020). The 7 principles.

https://universaldesign.ie/what-is-universal-

design/the-7-principles/the-7-principles.html.

Vaswani, M., Balasubramaniam, D., and Boyd, K. (2023).

A novel approach to improving the digital literacy

of older adults. In 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th Interna-

tional Conference on Software Engineering: Software

Engineering in Society (ICSE-SEIS), pages 169–174.

IEEE.

Who Can Use (2023). Who can use this color combination?

https://www.whocanuse.com/.

Yazdani-Darki, M., Rahemi, Z., Adib-Hajbaghery, M., and

Izadi, F. (2020). Older adults’ barriers to use tech-

nology in daily life: A qualitative study. Nursing and

Midwifery Studies, 9(4):229–229.

Yoo, H. J. (2021). Empowering older adults: Improving

senior digital literacy. American Association for Adult

and Continuing Education.

Yuan, S., Hussain, S. A., Hales, K. D., and Cotten, S. R.

(2016). What do they like? communication prefer-

ences and patterns of older adults in the united states:

The role of technology. Educational Gerontology,

42(3):163–174.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

58