Evaluating UX Factors on Mobile Devices: A Feasibility Study

Adriana Lopes Damian

a

, Cinthia Carrenho

b

, Graziela Martin

c

, Lucas Castro

d

, Bruna Brotto

e

,

Frederick Lucan

f

and Raquel Pignatelli da Silva

g

Eldorado Research Institute, Brazil

Keywords:

User Experience, UX Factors, UX Characteristics, Evaluation Methods.

Abstract:

The acceptance of consumers regarding software products determines their success of technologies, making

it a crucial topic in industrial research. In this context, the evaluation of User Experience (UX) can provide

benefits in understanding for practitioners and researchers before the launch of products in the market. The

literature encompasses works that focus on the assessment of UX for various software products, emphasizing

the importance of clearly evaluating UX characteristics for those involved in a project. This paper presents a

feasibility study with the participation of 25 practitioners engaged in the evaluation of UX for mobile devices,

analyzing UX problems concerning different UX factors presented in the literature. The application of these

factors was deemed easy and useful in understanding the quality of mobile devices before their market release.

The study aims to contribute to practitioners and researchers involved in the assessment of UX for mobile

devices, addressing different perspectives on product quality.

1 INTRODUCTION

The acceptance of consumers regarding software

products determines their success of technologies

(Wang et al., 2013). In this context, User Experience

(UX) can contribute to the acceptance of these prod-

ucts. Researchers and practitioners understand the

importance of providing a good user experience when

developing interactive software products (Kou and

Gray, 2019). For example, (Lallemand et al., 2014)

conducted a survey with 758 participants from differ-

ent fields and 35 nationalities, revealing that 83.9%

consider UX as central or very central to their practi-

tioner work. Thus, the prior evaluation of UX prod-

ucts can significantly contribute to product success.

Some works present studies from different per-

spectives of UX evaluation (Alves et al., 2021) (Je-

sus et al., 2022), focusing on experiments conducted

through sessions with users, providing insights for fu-

ture improvements. However, UX evaluations over

a longer period contribute to collecting more data

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0072-6958

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3730-9308

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-8203-4049

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8640-0034

e

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-9599-8519

f

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2540-1640

g

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-1203-877X

about the quality of a given product. One approach

that has been adopted by UX evaluation by compa-

nies is Dogfooding (Harrison, 2006). Through this

approach, company employees experience their prod-

ucts and services before they are launched in the mar-

ket. This can be a way for an organization to test

its products in the real world, obtaining feedback on

how end-users would use them. This approach has

been used by well-known technology market play-

ers such as Apple, Facebook, and Google (Soderquist

et al., 2016). For mobile devices, for example, we

can understand positive and negative aspects, such as

camera quality and adaptation of different used ap-

plications. In addition, equally important to conduct

UX evaluation is the understanding of different UX

characteristics discussed in the literature (Nakamura

et al., 2022) because it helps software development

team make decisions about product quality (Schrepp

et al., 2023), including the practitioners’ perceptions

concerning such characteristics.

Our paper presents a feasibility study that aims

to assess the practitioners’ perceptions, that working

in UX evaluation using Dogfooding approach about

factors that can characterize UX through evaluations

(Nakamura et al., 2022). To guide our research, we

explored the following research questions: RQ1 - Is

the use of UX factors understandable for practi-

tioners during problem analysis? and RQ2 - What

Damian, A., Carrenho, C., Martin, G., Castro, L., Brotto, B., Lucan, F. and Pignatelli da Silva, R.

Evaluating UX Factors on Mobile Devices: A Feasibility Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0012623600003690

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024) - Volume 1, pages 265-272

ISBN: 978-989-758-692-7; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

265

is the level of participants’ acceptance for this type

of analysis in mobile device development projects?

Our investigation was based on an action research

methodology (Petersen et al., 2014), which combines

theory and practice for the development of solutions

to real problems through collaboration between re-

searchers and practitioners. The results indicated that

the analysis of UX factors is feasible, as the factors

were applied coherently with the expectations of the

researchers. Furthermore, this study showed a pos-

itive acceptance from practitioners involved in UX

evaluation for a better understanding of the accep-

tance of consumers regarding mobile devices. Thus,

our work can contribute to other practitioners and re-

searchers working on UX evaluation, providing valu-

able insights for the continuous improvement of this

user experience dimension.

2 BACKGROUND

ISO 9241-210 defines UX as “a person’s perceptions

and responses that result from the use and/or antici-

pated use of a product, system, or service” (de Nor-

malisation, 2010). UX encompasses both pragmatic

aspects, focusing on the traditional usability features

that aid in task accomplishment and hedonic aspects,

involving sentiments and emotional responses from

using a product (Hassenzahl, 2018). For instance, a

product may be perceived as pragmatic if it efficiently

facilitates task completion, while it may be seen as

hedonic if it provides stimulation, identification or

evokes memories.

In terms of UX evaluation, practitioners and re-

searchers recognize its importance as it enables an un-

derstanding of how users apply and perceive a prod-

uct or service, facilitating improvements aligned with

user expectations (Moreno et al., 2013). This ap-

proach allows the identification of potential problems

in the applications usage, their causes and provides

suggestions for improvement. While various methods

exist for evaluating the UX of system products (Mar-

ques et al., 2018), many works primarily offer indi-

cations about the overall experience, necessitating a

deeper understanding of issues that can lead to a neg-

ative user experience.

Schrepp et al. (2023) investigated the importance

of UX aspects for different product types through

five independent studies, involving 361 participants.

They found that the significance of UX quality aspects

varies depending on the product type, offering valu-

able guidelines for UX developers and researchers

during the design and evaluation phases of interac-

tive products. Their conclusion emphasized that the

relevance of UX factors is subjective, varying among

individuals and different product categories.

Nakamura et al. (2022) conducted a systematic

mapping of UX factors for mobile devices based on

user reviews in app stores. The study identified 31

distinct factors, such as Compatibility, measured by

issues on a specific device or operating system version

and Attractiveness, defined as the user’s experience

and feelings towards a product in a particular situation

during evaluative judgment.

Given the escalating interest in UX within the sci-

entific community and industry, it is crucial to com-

prehend UX characteristics specific to certain types

of products. In addition, it is important to investigate

UX factors presented in the literature concerning the

practitioners’ perceptions.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

It is crucial to analyze the UX characteristics for dif-

ferent types of products to make decisions about prod-

uct quality, as highlighted by (Schrepp et al., 2023).

In our work, we are examining the feasibility of us-

ing a set of UX factors identified from user reviews

for mobile devices in general. In other words, partic-

ipants in UX evaluations use mobile devices in their

daily lives and share their perceptions about aspects

such as camera quality, connectivity, and available

applications in the market. For this purpose, a fea-

sibility study involving practitioners from a Brazilian

company has been planned. This company is involved

in both local and international projects, including the

evaluation of UX for mobile devices before their mar-

ket release.

3.1 UX Factors in UX Evaluation

In our previous work (Damian et al., 2023), we in-

vestigated the possibility of applying the factors iden-

tified by Nakamura et al. (2022) in the context of

UX evaluation of mobile devices. Twelve researchers

in three weekly meetings internally discussed this

work. The factors related to UX were reviewed and

problems from four mobile devices were selected to

be evaluated. After applying the factors to different

products, the researchers noticed that some of them

were not applicable to the context of product evalua-

tion. As a result, the factors are presented in Table 1.

Nevertheless, since this was an internal effort by the

involved researchers to create a new approach for en-

hancing UX analysis, it was decided that it would be

valuable to evaluate the perception of other individu-

als involved in this type of evaluation.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

266

Table 1: Adapted UX Factors for Mobile Devices UX Evaluation.

UX Factors Description

Accuracy

Characterizes discrepancies between the proximity of aspects experienced by

users and the value obtained in data measurement.

Attractiveness

Characterizes discrepancies representing positive and negative perceptions of a

product. What attracts the customer to that product.

Comparison

Characterizes discrepancies with comparisons to other products or comparisons

within the same product but in different software versions.

Ease of Use

Characterizes discrepancies about the effort required to use a specific functionality

or feature of the product. Ease of use can also be related to tutorials with missing

information. It does not characterize problems with the app/feature itself; the focus

here is on the user experience.

Satisfaction Characterizes praise and criticism regarding product features during its use.

Screen Interface

Discrepancies related to the appearance of the product (display), font and color

schemes, and icons.

Performance Discrepancies related to the product’s performance, given the configuration.

Customization

Characterizes discrepancies related to screen and feature/functionality

customization.

Bugs

Characterizes discrepancies about functionalities with issues during the use of

the product.

Crash

Characterizes discrepancies that present constant crashes in the use of a

functionality or feature.

Network Issues Discrepancies related to telephony network problems.

Exceeded Resources

Discrepancies related to excessive consumption of product resources, such as

memory and battery.

Software Update

Discrepancies related to updates, improvements, and changes to the operating

system.

Hardware Component

Hardware component that was implemented in different versions of the phone

hardware.

3.2 Feasibility Study Design

The feasibility study was meticulously planned to be

conducted in the industry within the scope of UX

evaluations for mobile devices before their market

launch. This scope encompasses both new devices

and operating system updates.

3.2.1 Context of UX Evaluation

Regarding UX evaluation participants, the company’s

own employees use these products and share their

perceptions of their quality via the Dogfooding ap-

proach. The product evaluation cycle begins with an

analysis of the minimum requirements to be met in

mobile devices, covering both hardware and opera-

tional system version. During the evaluation cycle,

which lasts an average of three to four months, vari-

ous methods are employed to characterize UX, such

as focus groups, weekly meetings, surveys, and the

use of an application that records suggestions for im-

provement/problem and automatically collects device

logs. Related to this last aspect, this contributes to

a more in-depth analysis of problems by developers.

Moreover, different roles play specific functions in

this type of analysis, such as UX analysts, analysts

responsible for problem screening, leaders for recruit-

ing and engaging participants, engineers responsible

for the tools used during evaluation and product man-

agers. These practices significantly contribute to the

improvement of product UX, as scenarios often not

identified by the testing team are revealed in such

evaluations (Silva et al., 2019). Additionally, we have

observed that it is possible to obtain a preview of end-

users’ perceptions.

3.2.2 Problem Selection

Sixteen problems reported by different users, from

eight different mobile devices and two Operating Sys-

tems, were randomly selected for analysis in the

study. This amount was chosen based on the aver-

age analysis workload of a practitioner responsible for

tracking issues reported by users during the review cy-

cle, forwarding them to different development teams,

such as camera experts, battery specialists, and others.

Evaluating UX Factors on Mobile Devices: A Feasibility Study

267

3.2.3 Participant Selection

Invitations were extended to practitioners with differ-

ent roles in mobile device UX evaluation to partic-

ipate in the study. Approximately 40 practitioners

were contacted and, of these, 25 voluntarily agreed

to participate. The study’s objective was explained to

the participants, emphasizing that they were to ana-

lyze problems reported in review cycles and classify

the most relevant UX factor. It was clarified also that

a single issue could be associated with more than one

factor. The study was planned to take place over a

7-day period, during which participants would con-

duct the analysis and remotely submit the results. Fol-

lowing this phase, a post-study questionnaire, consist-

ing of both open-ended and closed questions, was de-

signed to collect participants’ insights on the activity.

3.2.4 Questionnaire

Regarding participants’ acceptance, we applied

a questionnaire based on Technology Acceptance

Model (TAM) (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000) adding

also some open questions. This model has been ap-

plied to evaluate the acceptance of a large set of tech-

nologies about users’ perceived ease of use, the de-

gree to which a person believes that using a specific

technology will be free effortless and the perceived

usefulness that a person believes that using a spe-

cific technology will enhance his or her work per-

formance (Maranguni

´

c and Grani

´

c, 2015). In addi-

tion, according to TAM, the user’s behavioral inten-

tion to use a specific technology is determined by

perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. The

TAM statements adapted for our study are presented

below. Regarding the adapted TAM statements, par-

ticipants provided their answers on a seven-point Lik-

ert scale, as follows: “Totally Agree, Strongly Agree,

Partially Agree, Neutral, Partially Disagree, Strongly

Disagree and Totally Disagree”.

PERCEIVED EASE OF USE: E1. My interaction

(comprehension of the information) with these UX

factors was clear and understandable; E2. Interact-

ing (comprehension of the information) with these UX

factors does not require a lot of mental effort; E3. I

find these factors easy to understand about user ex-

perience information products; and E4. I find it easy

to make these factors do what I want (user experience

information product overview).

PERCEIVED USEFULNESS: U1. Using these fac-

tors improves my performance to better understand

aspects of the product; U2. Using these factors in my

work has improved my productivity in understanding

aspects of the product; U3. Using these factors en-

hances my effectiveness in understanding aspects of

the product; U4. I consider these factors useful for

product analysis.

INTENTION TO USE: I1. Assuming I had enough

time to analyze the UX of a product, I do intend to

use these factors; I2. Whereas if I could choose any

method to analyze the UX of a product, I predict I

would use these factors.

3.2.5 Feasibility Study Execution

For the execution of the study, a questionnaire con-

taining the description of UX factors and the list of

issues was provided to the participants. This allowed

them to categorize the problems based on the most

relevant factors and they also had the opportunity to

review each factor. After completing this phase, a

post-study questionnaire was sent to each participant.

We conducted a pilot study with four participants,

according to the planned procedures. After analysing

the problems and completing the questionnaires, we

held a meeting with the participants to assess whether

they faced any challenges with the study materials and

to gather their insights on this type of research. After

this meeting, we determined that there were no im-

pediments to continuing the study with the remaining

participants.

4 RESULTS

Below are the results obtained in the evaluation of the

feasibility of applying UX factors. Table 2 shows the

number of problems analyzed in the study and the

factors applied by one of them. Regarding the de-

scription of the problems, we omitted it in Table 2

due to the confidential rules of our projects. Table 2

also highlights the factors expected to be applied by

researchers. Given the qualitative nature of this anal-

ysis, it is expected that a problem may be related to

more than one UX factor explored in this study. Re-

garding the analysis conducted, it’s possible to notice

that each one of the factors was utilized by the partic-

ipants, although, they utilized one or more of the fac-

tors. In the case of Problem 2, for example, it can be a

problem related to device functionality (Bugs) after a

software update (Software Update) that impacted the

Wi-Fi connection (Network Problem).

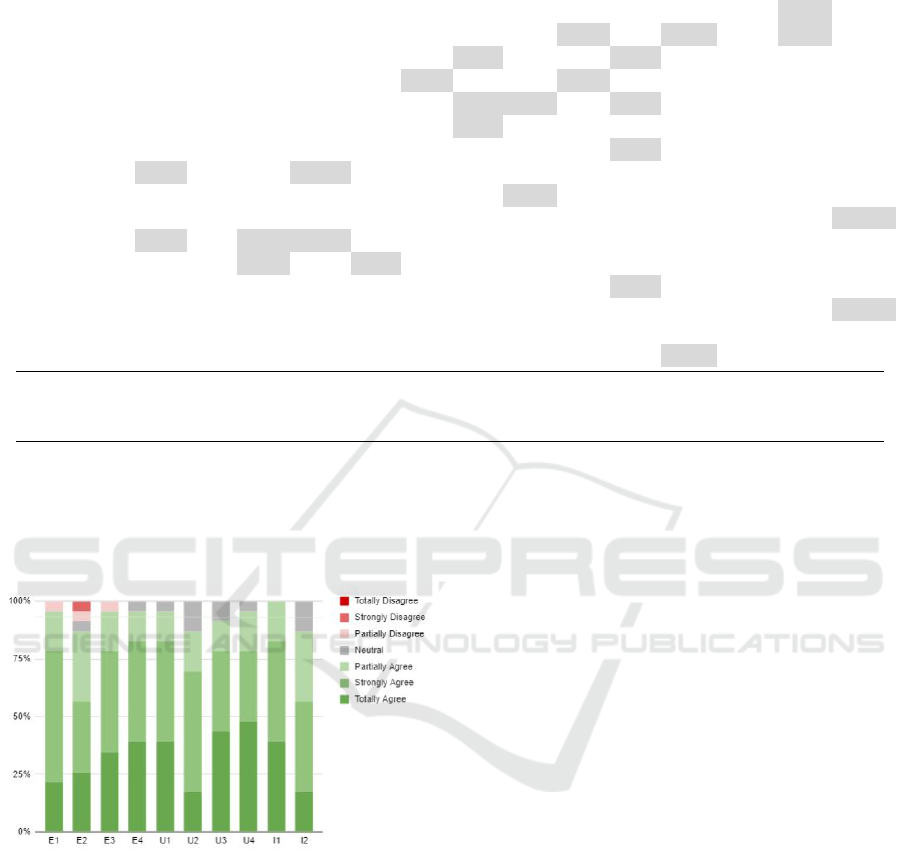

Regarding the TAM indicators, participants pro-

vided their answers regarding the level of acceptance

of the statements of each indicator using a seven-point

scale, with response options ranging from Strongly

Agree to Strongly Disagree. Figure 1 shows the par-

ticipants’ level of acceptance for the indicator Ease of

Use (P1 to P4), Usefulness (U1 to U4) and Intention

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

268

Table 2: UX problems concerning UX factors.

UX Problem Ac. At. Co. E.U. Sa. S.I. Pe. Cu. Bu. Cr. N.I. E.R. S.U H.C.

Problem 1 5 1 2 1 6 1 1 25

Problem 2 1 3 1 17 7 11 12

Problem 3 1 10 6 22 5

Problem 4 13 6 19 5 3

Problem 5 8 6 10 21 2

Problem 6 2 5 24 3 2 3

Problem 7 3 10 25

Problem 8 13 15 8 5 6

Problem 9 8 7 8 21

Problem 10 6 12 21

Problem 11 14 8 13 9 6

Problem 12 23 14 3

Problem 13 5 9 24

Problem 14 9 8 22

Problem 15 15 12 17

Problem 16 3 8

24

Ac. - Accuracy; At. - Attractiveness; Co. -Comparison; E.U. - Ease of Use; Sa. - Satisfaction;

S.I. - Screen Interface; Pe. - Performance; Cu. - Customization; Bu. - Bugs; Cr. - Crash, N.I. -

Network Issues, E.R. - Exceeded Resources, S.U. - Software Update, and H.C. - Hardware Component.

to Use (I1 and I2), where the vertical axis of the graph

refers to the statements of each of the indicators and

the horizontal axis refers to the participants’ level of

acceptance. The bars represent the participant codes

(P1, P2, and so on).

Figure 1: Participants’ acceptance of UX factors.

The majority of responses were positive, indicat-

ing a positive acceptance of the UX problem analysis

process. We organized the participant’s answers into

different categories, which represent the participants’

perceptions. In terms of the Ease of Use construct, P6

and P9 state that they did not encounter difficulties

applying this type of analysis: ’It was smooth; the de-

scription of the factors was very helpful’ and ’The de-

scription of the factors was clear and for most cases,

the application was intuitive.’ Although the major-

ity stated that this is an ease-to-implement analyti-

cal process, it was noticed in the feedback the diffi-

culty in understanding some factors: ’In my opinion,

some factors do not have a very clear description;

more examples could be given to facilitate its appli-

cation’ (P3) and ’I had doubts in some answers, espe-

cially between Bug, Crash and Accuracy; they seemed

like the same response’ (P15). To enhance the under-

standing of each factor, some participants suggested

the inclusion of more examples for a better com-

prehension of a UX factor based on the problems,

as mentioned by P8: ’User reports do not always di-

rectly indicate all the UX factors that could be linked

to that problem.’ We agreed that providing more ex-

amples could reduce uncertainty for some participants

during the analysis, as observed in the report from P2:

’In some cases where I couldn’t fit the problem into

the available options, I used the Bug option.’ An-

other aspect noticed by the participants was the lack

of clarity in the problem reports from UX evalua-

tion participants, which is a limitation in this type of

evaluation, as reported by P20: ’Most of the factors

seemed clear and sufficient to categorize user issues.

However, I think that a few pieces of feedback don’t fit

completely,’ and P10: ’The majority of feedback were

easy to understand, but there are always cases that

require a bit more attention to be comprehended.’

Regarding the usefulness of this type of anal-

ysis, different participants affirm that this analysis

supports the understanding of the device features

that are affected and the development of quality

metrics during the project and after the products

are launched in the market, as seen in the follow-

ing quotes: ’I think these factors are highly useful;

they serve as a comprehensive classifier and filter for

Evaluating UX Factors on Mobile Devices: A Feasibility Study

269

problems and device features...’ (P4); ’The utility of

the factors could collaborate with metrics during the

project development and after its launch’ (P5); ’...

serve as a well-elaborated foundation for analyzing

CRs and user feedback’ (P8); ’I believe it is useful

during the evaluation cycle to map the most affected

areas and, overall, what the user is reporting’ (P13);

’The factors are extremely useful, whether in the im-

plementation phase, pre-launch maintenance or post-

launch in the market’ (P16). Additionally, a better

understanding of the affected areas of the products

and the problems fix, which are included in weekly

releases, contributes to the engagement of users par-

ticipating in the UX evaluation, as perceived by P14:

’I agree because the improvement of the UX always

leads to their loyalty to the brand, caused by the feel-

ing of being heard and having their problems solved’.

The participants’ responses also indicate that

through the ’analysis of UX factors, a better un-

derstanding for those involved in product quality

can be achieved: ’I agree that the analysis of each

of the factors shown in the research can help im-

prove the quality of the product’ (P15); ’The user

responses, whether from end consumers or partici-

pants in the evaluation, actively shape the actions, im-

provements and corrections of the product. Therefore,

understanding this information is a crucial step in

decision-making in the process for product improve-

ment’ (P16); ’UX factors play a fundamental role in

product quality analysis, being extremely useful in all

stages of development’ (P17). Consequently, differ-

ent stakeholders in project management, such as man-

agers, developers, testers and UX specialists, can pri-

oritize issue resolutions and product improvements.

Regarding the intention to use, we’re aware that

a new activity in an ongoing process may not be ac-

cepted by all those involved. However, the responses

to most open-ended questions from participants sug-

gest a positive predisposition for the adoption of this

type of analysis. P5 and P17 state that such analy-

sis would support a better understanding of a prob-

lem before forwarding it to the development team:

’I would apply it in my daily activities; I believe it

would help in a better understanding of the problems’

(P5) and ’The application of these factors is crucial to

ensure that products meet user expectations, are intu-

itive to use, and offer a pleasant experience. There-

fore, the application of these factors through a system

would be a highly recommended choice to improve the

quality and success of new products’ (P17).

Still, when applying these factors in practice, it is

beneficial to adapt the process of evaluating prob-

lems reported during UX analyses. This allows for

a deeper understanding of the key roles involved in

this analysis, such as UX analysts and developers.

P11 and P22, for example, provided such insights: ’If

we raise awareness and discuss new good practices

for factors, it would be a viable option to adopt simi-

lar practices globally’ (P11) and ’As a developer, it is

unclear to me how and when these factors will be as-

signed to a CR (Change Request). During triage? In

this case, would the factors already be applied when

I receive the CR?’ (P22). Thus, the factors can be

widely adopted and viewed by all those involved in

the project. Consequently, it is possible to observe

that incorporating these factors into problem analy-

sis can positively contribute to product development

projects that will be launched in the market.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Findings

In reference to our findings regarding to RQ1 (Is the

use of UX factors comprehensible by practitioners

during problem analysis?), the results presented in

Table 2 indicated that the majority of the employed

factors are related to the analysis expected by the

main researchers. Since this is a qualitative analy-

sis, we understand that the use of most factors for a

specific problem may indicate that the participants un-

derstood them. However, some aspects were observed

that could affect this analysis, such as the lack of in-

formation from users who submit their evaluations of

the products. As the problem sample was randomly

selected, there were some reports with limited infor-

mation. Additionally, some participants had difficul-

ties with the factors’ description, indicating the need

for more examples in this context to minimize un-

certainties in the use of factors during problem anal-

ysis. Therefore, we plan to include more examples

in the description of the factors and also incorporate

this activity into our analysis process, indicating the

key roles involved in this analysis and the stage at

which such problems can be evaluated regarding UX

aspects. Thus, the results of the feasibility study indi-

cate that the description of the factors is feasible and

it was possible to understand the main limitations for

the use of these factors during evaluation.

For RQ2 (What is the level of participants’ accep-

tance for this type of analysis in mobile device devel-

opment projects?), utilizing the TAM revealed partic-

ipants’ acceptance of this analysis type. The quan-

titative results demonstrated predominantly positive

responses, as depicted in Figure 1. Regarding user

perceptions, while some indicated difficulties in un-

derstanding factor descriptions and others felt a lack

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

270

of examples, the majority of participants highlighted

the importance of this type of analysis. They empha-

sized the ability to comprehend the affected character-

istics of the device and the potential to formulate met-

rics to evaluate product quality. Based on the partic-

ipants’ responses, it became apparent that the aspect

that most influences the intention to use the factors is

their utility in analyzing product quality.

5.2 Threats to Validity

The threats that may affect the validity of our study re-

sults (Falessi et al., 2018) are described below, along

with the treatment for each of them.

Internal Validity. An identified threat is the sharing

of information between participants during the study.

To address this threat, the study’s selection and ma-

terials were individually sent to participants, as par-

ticipants don’t need to be close. This minimizes the

identification of other participants, thus reducing the

possibility of communication between them. Limited

information regarding problems can also affect the in-

terpretation of UX factors.

External Validity. Validity of the assessed problems

as a representative sample. To mitigate this threat,

16 problems were randomly selected from different

projects. Additionally, this number is related to the

average number of problems analyzed by a triage an-

alyst, reflecting a real activity in this company.

Construct Validity. Regarding UX factors, as these

are qualitative data, they were discussed in vari-

ous meetings by the researchers beforehand to mit-

igate misunderstanding about the problems. About

the adoption of TAM, it has been employed and

adapted for the evaluation of different technologies

(Maranguni

´

c and Grani

´

c, 2015).

Conclusion Validity. The short period of use of UX

factors in problem analysis. However, this is an initial

result and the findings cannot be generalized.

6 RELATED WORKS

Soleimani and Law (2017) present an empirical study

and highlight the importance of using a methodolog-

ical approach to measure UX. The main objective of

this study was to recognize emotions via the Think-

Aloud technique. The empirical study was carried out

with 46 participants using an online shopping plat-

form to evaluate each person’s emotional experiences

in different sessions. As the study was exploratory

in nature, the main intention was to develop a practi-

cal approach to explore momentary perceptions and

user interactions regarding the qualities of a prod-

uct/service. The techniques applied do not require any

additional expense or equipment and they can be im-

plemented in any work environment.

Fernandez et al. (2013) present the results of a

family of empirical experiments executed to compare

the proposed inspection method WUEP (Web Usabil-

ity Evaluation Process) with a well-known inspection

method - HE (Heuristic Evaluation) regarding its Ef-

fectiveness, Efficiency, Perceived ease of use and Per-

ceived satisfaction of use. To evaluate the results, the

authors did a quantitative analysis of the results and

tested all the null hypotheses. The statistical analy-

sis and meta-analysis of the data obtained separately

from each experiment indicated that WUEP is more

effective and efficient than HE in the detection of us-

ability problems. The evaluators were also more satis-

fied when applying WUEP and found it easier to use

than HE. The experiment concluded that the WUEP

method performed better for all the 4 points analyzed.

Regarding the works above, we notice the impor-

tance of evaluating the UX of a system and show a

specific approach to supporting the collection of user

feedback through evaluation sessions (Soleimani and

Law, 2017). Our work, on the other hand, evaluates

UX during a period of 3 to 4 months, including the

methods to support it, which allows us to figure out

the users’ perceptions. While the paper from (Fer-

nandez et al., 2013) evaluated usability for web appli-

cations during the development process considering

Effectiveness, Efficiency, Perceived ease of use and

Perceived satisfaction, our work evaluated the appli-

cation of 14 factors in different types of real issues

reported by users of your daily life. Our work focuses

on UX factors, that can help to figure out pragmatic

or hedonic aspects of mobile devices, contributing to

the quality of these products.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented a feasibility study on the appli-

cation of UX factors in the analysis of real problems

in mobile devices’ UX evaluations. Considering the

action research methodology, we systematically eval-

uated UX factors for mobile devices, identifying key

elements for use in projects focusing on UX evalua-

tion. This kind of analysis can contribute to understat-

ing the main problems, both pragmatic and hedonic,

that may impact the end user’s perception of mobile

devices before their market launch. Based on the re-

sults obtained, the consensus among practitioners is

that this form of analysis is valuable for comprehend-

ing the fundamental factors of UX. While the majority

agreed that it is easy to implement this type of anal-

Evaluating UX Factors on Mobile Devices: A Feasibility Study

271

ysis, we observed the need for improvements in de-

scribing the factors to be implemented in the daily ac-

tivities of the practitioners dealing with the UX eval-

uation. Our perspective is that these factors can high-

light the hedonic aspects related to the UX in evalu-

ations, once the predominant focus of developers lies

in fixing and enhancing the pragmatic aspects.

For future work, we intend to incorporate exam-

ples of problems related to the factors to facilitate

the UX problem analysis. Additionally, we intend

to refine the problem analysis process to incorporate

UX factors, covering the necessary activities and met-

rics that can assist this type of evaluation in future

projects. Moreover, it will also be possible to ana-

lyze the contributions of UX factors toward a deeper

software quality comprehension in this aspect.

REFERENCES

Alves, F., Aguiar, B., Monteiro, V., Almeida, E., Marques,

L. C., Gadelha, B., and Conte, T. (2021). Immersive

ux: A ux evaluation framework for digital immersive

experiences in the context of entertainment. In ICEIS

(2), pages 541–548.

Damian, A. L., Teixeira, L., Carrenho, B. C., Ferreira, B. B.,

Bentes, B. A., Tordin, M. G., Martin, M. G., Castro,

M. L., Brotto, M. B., Pereira, B. V., et al. (2023). Ex-

ploring ux factors through the dogfooding approach:

An experience report. In Proceedings of the XXII

Brazilian Symposium on Software Quality, pages 236–

243.

de Normalisation, O. I. (2010). Iso 9241-210: Ergonomics

of human-system interaction-part 210: Human-

centered for interactive systems. International Orga-

nization for Standardization.

Falessi, D., Juristo, N., Wohlin, C., Turhan, B., M

¨

unch, J.,

Jedlitschka, A., and Oivo, M. (2018). Empirical soft-

ware engineering experts on the use of students and

professionals in experiments. Empirical Software En-

gineering, 23:452–489.

Fernandez, A., Abrah

˜

ao, S., and Insfran, E. (2013). Em-

pirical validation of a usability inspection method for

model-driven web development. Journal of Systems

and Software, 86(1):161–186.

Harrison, W. (2006). Eating your own dog food. IEEE

Software, 23(3):5–7.

Hassenzahl, M. (2018). The thing and i: understanding the

relationship between user and product. Funology 2:

from usability to enjoyment, pages 301–313.

Jesus, E. A., Guerino, G. C., Valle, P., Nakamura, W. T.,

Oran, A. C., Balancieri, R., Coleti, T. A., Morandini,

M., Ferreira, B., and Silva, W. (2022). An experimen-

tal study on usability and user experience evaluation

techniques in mobile applications. In ICEIS (2), pages

340–347.

Kou, Y. and Gray, C. M. (2019). A practice-led account

of the conceptual evolution of ux knowledge. In Pro-

ceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Fac-

tors in Computing Systems, pages 1–13.

Lallemand, C., Koenig, V., and Gronier, G. (2014). How

relevant is an expert evaluation of user experience

based on a psychological needs-driven approach? In

Proceedings of the 8th Nordic conference on human-

computer interaction: Fun, fast, foundational, pages

11–20.

Maranguni

´

c, N. and Grani

´

c, A. (2015). Technology accep-

tance model: a literature review from 1986 to 2013.

Universal access in the information society, 14:81–

95.

Marques, L. C., Nakamura, W. T., Valentim, N. M. C.,

Rivero, L., and Conte, T. (2018). Do scale type tech-

niques identify problems that affect user experience?

user experience evaluation of a mobile application (s).

In SEKE, pages 451–450.

Moreno, A. M., Seffah, A., Capilla, R., and Sanchez-

Segura, M.-I. (2013). Hci practices for building usable

software. Computer, 46(04):100–102.

Nakamura, W. T., de Oliveira, E. C., de Oliveira, E. H., Red-

miles, D., and Conte, T. (2022). What factors affect

the ux in mobile apps? a systematic mapping study on

the analysis of app store reviews. Journal of Systems

and Software, 193:111462.

Petersen, K., Gencel, C., Asghari, N., Baca, D., and Betz,

S. (2014). Action research as a model for industry-

academia collaboration in the software engineering

context. In Proceedings of the 2014 international

workshop on Long-term industrial collaboration on

software engineering, pages 55–62.

Schrepp, M., Kollmorgen, J., Meiners, A.-L., Hinderks, A.,

Winter, D., Santoso, H. B., and Thomaschewski, J.

(2023). On the importance of ux quality aspects for

different product categories.

Silva, E., Tanaka, E., and Tordin, G. (2019). Dogfooding:

” eating our own dog food” in a large global mobile

industry player. In Proceedings of the 14th Interna-

tional Conference on Global Software Engineering,

pages 52–57.

Soderquist, K., Tirabeni, L., and Pisano, P. (2016). Em-

ployee engagement practices in support of open inno-

vation. In 3rd Annual World Open Innovation Confer-

ence, pages 15–16.

Soleimani, S. and Law, E. L.-C. (2017). What can self-

reports and acoustic data analyses on emotions tell us?

In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Designing

Interactive Systems, pages 489–501.

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical exten-

sion of the technology acceptance model: Four longi-

tudinal field studies. Management science, 46(2):186–

204.

Wang, T., Oh, L.-B., Wang, K., and Yuan, Y. (2013). User

adoption and purchasing intention after free trial: an

empirical study of mobile newspapers. Information

Systems and e-Business Management, 11:189–210.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

272