The Perceived Learning Behaviors and Assessment Techniques of

First-Year Students in Computer Science: An Empirical Study

Manuela Petrescu

a

and Tudor Dan Mihoc

b

Department of Computer Science, Babes¸ Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Keywords:

Learning, Online, Students, Computer Science, Survey, Evaluation, Stress.

Abstract:

The objective of our study is to ascertain the present learning behaviors, driving forces, and assessment tech-

niques as perceived by first-year students, and to examine them through the lens of the most recent devel-

opments (pandemic, shift to remote instruction, return to in-person instruction). Educators and educational

institutions can create a more accommodating learning environment that takes into account the varied needs

and preferences of students by recognizing and implementing these findings, which will ultimately improve

the quality of education as a whole. Students believe that in-person instruction is the most effective way to

learn, with exercise-based learning, group instruction, and pair programming. Our research indicates that, for

evaluation methods, there is a preference for practical and written examinations. Our findings also underscore

the importance of incorporating real-world scenarios, encouraging interactive learning approaches, and creat-

ing engaging educational environments.

1 INTRODUCTION

Education in the present day faces a number of novel

challenges. These problems originate either from

global unfortunate events, such as the pandemic, or

from mandated educational activities, such as dis-

tance e-learning, as a result of these events (Gutierrez-

Aguilar et al., 2023). These difficulties have had a

substantial impact on the quality of education and stu-

dents’ ability to learn. As a result, students may strug-

gle to keep track of their schoolwork and fall behind;

their academic performance may suffer as a result, as

will their motivation. This will eventually jeopardize

their ability to achieve their academic objectives and

realize their full potential. Therefore, it is critical that

teachers provide enough support and resources to help

students overcome these obstacles and stay on track

with their studies.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced both teachers

and students to switch from traditional in-person in-

struction to online learning environments (Lemay

et al., 2021).

Although most campuses have faculty members

with training to guarantee the quality of the content,

few have created strategies for this type of interac-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9537-1466

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2693-1148

tion with students. Some suggestions to improve stu-

dent participation and engagement in online learn-

ing environments are provided in (Neuwirth et al.,

2021). They proposed a framework that academic de-

partments might use to create policies that cover best

practices and recommendations for post-pandemic

synchronous and asynchronous virtual classrooms.

Any attempt to solve these problems is hampered

by the lack of knowledge about the preferences and

study habits of the students after the quarantine pe-

riod. We attempt to close this knowledge gap in this

study by finding out what students think is the best ap-

proach to carrying out the teaching and learning pro-

cess.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Several strategies have been proposed to increase the

efficacy of instruction (Liu et al., 2022; Seikkula-

Leino et al., 2010), with many focusing on com-

puter science teaching methods (Salas, 2017; George,

2020). In addition, some offer resources to computer

science instructors (Hazzan et al., 2020), and suggest

technical professional development and collaboration

tactics for teachers (Wang et al., 2021).

Several research papers have been published on

the topic of online student motivation (Baquerizo

Petrescu, M. and Mihoc, T.

The Perceived Learning Behaviors and Assessment Techniques of First-Year Students in Computer Science: An Empirical Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0012674000003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 2, pages 405-412

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

405

et al., 2020), online course assessments (Vegliante

et al., 2018), and focus of elements such as teacher

collaboration strategies and technical professional de-

velopment (Wang et al., 2021).

Online classes have the benefit of allowing stu-

dents to learn at their own pace using text or video

resources, which can facilitate learning. Before lec-

tures, students can access the materials, which allows

them to ask more questions and complete more diffi-

cult assignments. (Sobral, 2020).

The student dropout rate is a problem educators

face on a regular basis. The percentage of students en-

rolled who do not graduate with a degree or dropout

varied significantly in European countries, from a low

14,4% in the UK, to approximately 29% in Germany,

according to (Heublein et al., 2017). The highest

value, according to EU reports (Centre for Higher Ed-

ucation Policy Studies, 2015) is 60,6% in France. On-

line or hybrid learning environments (de Sousa et al.,

2022) were also considered as a response to dropout

rates in traditional classroom settings. There are other

factors that affect the dropout rate, including aca-

demic achievement, starting age, and parental educa-

tional background (Araque et al., 2009).

Fear of failure can also be a factor that slows

academic development. (Martino, 1993) offers some

goal-setting strategies that can help young students

avoid becoming failure-accepting students.

There is a lot of literature related to mechanisms

that can be employed by people when faced with chal-

lenging circumstances that carry a high risk of failure

and possible harm to their self-esteem (Norem and

Cantor, 1986). In the literature, as guideline for ed-

ucators, the main approach to this matter is mostly

by creating a supportive and nurturing environment,

provide educational treatment, and use autonomy-

supportive teaching styles.

3 STUDY SETUP

Scope: We aim to determine the current learning

habits, motivations, and evaluation methods in the

freshmen students opinion and analyze them from the

perspective of the changes in the last period (COVID,

transition to online teaching, transition back to face-

to-face teaching).

The COVID-19 pandemic’s restrictions on this

generation of students also had a direct impact on

their initial years of high school study: social isola-

tion, a sudden switch to online instruction for a year,

and after to a return to in-person instruction from

teachers.

We were interested in students’ perspective on a

stage in life when, after graduating high school and

enrolling at the university , they had little time to ad-

just to the new academic environment.

We aim with this up-to-date data to fill in the gaps

in our understanding of the students.

The research questions are:

- What drives students’ primary motivation to ac-

quire knowledge?

- Which evaluation method is considered by stu-

dents to be the most equitable, and why?

- What do students think are the most effective

ways to learn?

The authors formulated these research questions

after defining the study objective.

Setup. In order to explore the answers to our research

questions, we designed a survey addressed to young

students. We sent the survey link to students in the

eighth week of the first semester, which were ran-

domly allocated to one of the authors of this research

in the Computer Science Architecture.

We outline the purpose of collecting their input

and the intended use of the gathered data in an effort

to boost engagement. A brief speech about our re-

search and expressing our appreciation for their time

in responding served as the sole source of motivation.

We also noted the anonymity of the survey.

Participants. A group of 43 students enrolled in the

first year of computer science in the English line of

study participated in the survey. The initial set of

participants consisted of 67 students, of whom 43 de-

cided to participate. The selection of the 67 students

that were required to participate was aleatory; the stu-

dents were randomly selected from the students as-

signed to classes with one of the authors of this study.

There was no discrimination between the students;

all received the survey link. Participation was op-

tional and we did not use any reward mechanism for

participation, except for the motivational speech men-

tioned above. We obtained 64.17% responses from

the initial set of participants.

Study Design. After analyzing and deciding on the

research questions, we designed the survey. The pro-

cess of elaborating the questions was made up of a

series of steps: each author proposed some questions

that formed the first draft and we discussed, analyzed,

and modified the questions until we reached consen-

sus.

We used open questions because they provide

more information about the students’ thoughts and

can better reflect their perceptions of reality. The

questions were asked in the student’s native language,

even if the participants were enrolled in the English

line to obtain more descriptive and complex answers.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

406

We asked positive and negative questions to avoid

bias, and we asked the students to motivate their re-

sponses rather than specify a reason or a learning

method. We provide the learning methods examples

only in the last question as we did not want to influ-

ence previous responses. The list of survey questions

is shown in Table 1.

3.1 Methodology

In the eighth week of the second semester, we con-

ducted an online survey using both accountable and

open questions. Accountable questions facilitate

working with and interpreting some facts, and open

questions offer a further level of insight. To eval-

uate and interpret responses to open questions, we

used quantitative techniques, particularly question-

naire surveys, according to the guidelines established

by the empirical community (Ralph, Paul (ed.), 2021).

For the interpretation of the text, we apply the defini-

tion of theme analysis found in (Braun et al., 2019).

These techniques have already been applied in other

studies related to computer science (Petrescu and Mo-

togna, 2023; Motogna et al., 2021; Petrescu et al.,

2023).

The following steps constitute the text analysis

methodology.

(1) In order to identify the keys in the text, two

researchers performed an independent analysis.

(2) Using techniques that include generalization,

removal, and reassignment of significant items with

low prevalence to similar themes or classes, we clas-

sified important items based on shared themes or

classes.

(3) In the last phase, all authors review the pro-

cess with careful consideration in order to assess the

degree of trust in the methodology. Examining and

debating numerous topics, explanations and corrobo-

rating data related to the categorization procedure was

part of this process.

We calculated the frequency of the keywords used

in the answers. Some student submissions featured

only one or two ideas, while others provided up to

four arguments to support their choice of research top-

ics. Thus, an answer could include additional things

or significant words. We used the calculated preva-

lence of several key items, classified them, and com-

pared them with the total number of responses re-

ceived. As a result, the total percentages will exceed

100%.

Data Collection. Several steps were taken in the pro-

cess of developing survey questions. Initially, we de-

veloped the study objectives and determined the scope

of the article. Each author supplied a list of survey

questions based on these. We studied and debated

the proposed collection of questions before deciding

which questions would be selected for the survey.

The questions were translated from English into

the students’ native language, allowing them to re-

spond in their preferred language. We used this

strategy to promote student participation. We em-

ployed automatic language translation technologies to

translate them into English before having the authors

double-check the translation.

To increase the number of responses, we left the

survey open for two weeks. We distributed the survey

link to the student group so we could gather responses

anonymously, allowing students to respond when and

how they chose.

The collected answers were pre-processed prior to

analysis, eliminating some special characters, empty

lines, and spaces.

3.2 Q1 - What Drives Students’

Primary Motivation to Acquire

Knowledge?

Motivation is a key component in the learning pro-

cess, it can be positively or negatively influenced, de-

pending on a sum of factors. We wanted to explore

which are these factors for first-year students in com-

puter science, as in this period, the are still deeply in-

volved in the learning process but are mature enough

to appreciate and take into consideration a large broad

range of factors. We asked them to describe what fac-

tors motivate them to learn a course and what factors

discourage them.

What Are the Factors that Motivate Students to

Learn the Content of the Course?

We grouped the factors mentioned by students in two

major classes, one set of factors are related to eco-

nomical perspectives and the second set of factors re-

lated to personal reasons:

• Economic: Will help me in the future, Useful, To

pass (the exam), Important

• Personal: Interesting, I like (the topics), I like the

teacher

A set of factors such as ”To learn how different com-

puter programs work” have a small prevalence, so we

decided to place them in the class ”Other”. The per-

centages of motivational factors, grouped by classes,

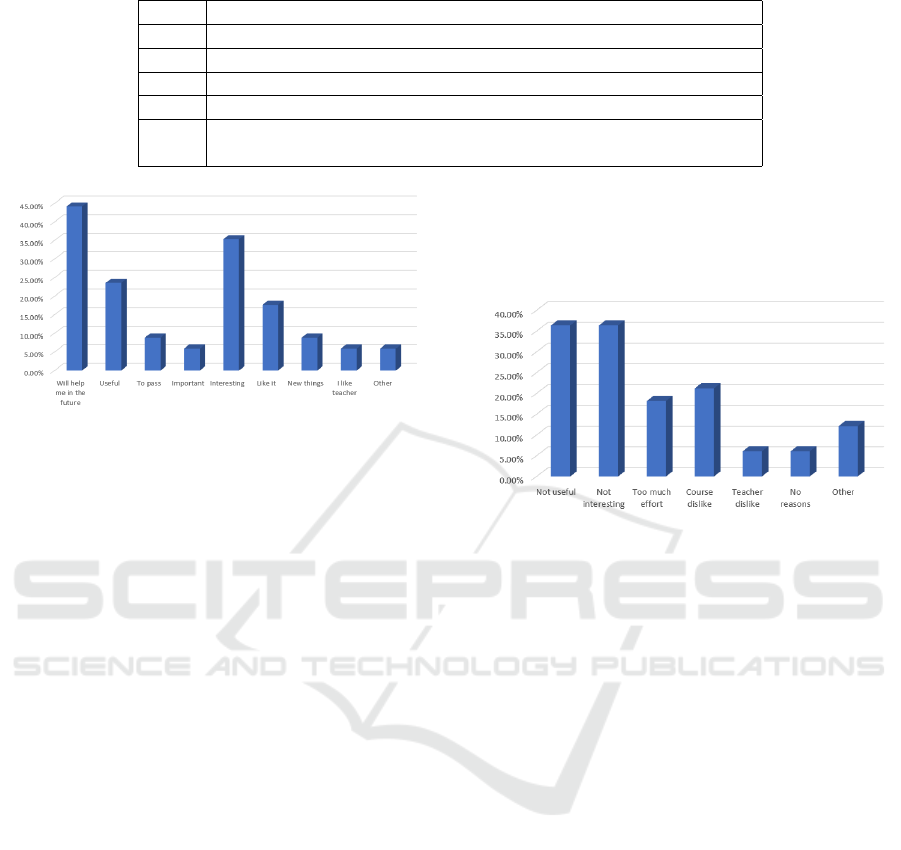

mentioned by the students are presented in Figure 1.

Economic factors seem to have a higher preva-

lence compared to personal / emotional factors. The

responses of many students reflected this aspect: ”If

the things I learn in the course are up-to-date and will

help me in the future job”,”If the course is useful to

The Perceived Learning Behaviors and Assessment Techniques of First-Year Students in Computer Science: An Empirical Study

407

Table 1: Survey Questions.

Q1 What are the factors that motivate you to learn?

Q2 What are the factors that discourage learning a topic or a course?

Q3 What do you consider to be the worst form of evaluation and why?

Q4 What do you consider to be the best form of evaluation and why?

Q5 Which are in your opinion the best teaching methods?

Q6 Which teaching methods worked best for you? What do you use?

(online courses, face-to-face teaching, pair programming)

Figure 1: Factors that motivate students to learn.

me, I study it, if not, I don’t”, ”The main reason is

represented by the existence of an exam that forces

me to study”.

Personal and emotional factors are related to each

individual’s passions: ”I am curious and I like to

learn new things”, ”Because I like it”, ”If it is a topic

that interests me”. The personal relationship with the

teacher seems to count less at this level, only 5.88%

of the students mentioning it, compared to 35.29% of

students mentioning ”Interesting” as a learning fac-

tor.

What Are the Factors That Discourage Learning a

Topic or a Course?

The main discouraging factors are the mirror reflec-

tion of the most motivating factors: Not Interesting

and Not useful” ”It is hard, the teacher is demand-

ing, exams are hard, I don’t find it interesting, it

wouldn’t help me in the future”, ”It is useless in my

development”, ” It does not captivates my attention”,

”the uselessness of course in life”. Not liking the

course and the topics or the teacher are discouraging

factors: ”Disinterest in the topic”, ”If I am not

interested”, ”Because I do not like the teacher or the

topics”.

A large group mentioned too much effort to be a

discouraging factor, others referred to stress, lack of

time, theoretical and unuseful learning materials: ”If

there is too much to learn and I do not have the time

necessary to retain everything”, ”Exam stress”, ”If it

involves memorization and not thinking”.

Other answers reflect a learning mindset and a

positive attitude: ”There are no many reasons, it is

always worth trying to learn something”. The per-

centages for the factors that discourage learning are

shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Factors that discourage students to learn.

In Conclusion. Based on the answers to the ques-

tions, we can establish that the most important rea-

sons are the how useful is the learned information and

how interesting are the topics in the course. Personal

relationship with the teacher seem to be less impor-

tant, however, other factors such as too much effort or

lack of time can negatively impact learning.

3.3 Q2 - Which Evaluation Method Is

Considered by Students to Be the

Most Equitable and Why?

To find out, we decided to ask the students which

forms of evaluation are in their opinion the best and

which are the worst and why. Students prefer to

be evaluated on written exams, practical projects, or

practical examinations, or to have projects during the

course. The percentages are shown in Figure 3.

As we did not want to create bias, we asked about

the worst form of evaluation. If the oral evaluation

scored low in the best forms of evaluation, it scored

high in the worst form of evaluation. The surprise test

was the second worst form of evaluation mentioned,

as can be seen in Figure 4. Written examination was

mentioned third as a bad form of evaluation, but only

for programming courses: ”Tests written on paper,

especially for topics that are run in computer pro-

grams”, ”Reproducing, in writing, the theory or pro-

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

408

Figure 3: Best forms of evaluations methods in student’s

opinions.

gram sequence step-by-step, especially when a def-

inition is formulated strangely and/or I do not have

the possibility to test, in real time, what my program

does”

Figure 4: Worst forms of evaluations methods in student’s

opinions.

The students based their opinion on different rea-

sons, the most important being stressful situations,

not enough time and learning memorizing / Unuse-

ful information.

Students do not like stressful situations that ap-

pear during exams, especially in oral examinations;

the stress is induced by the situation and the poten-

tial lack of time ”Personally, I do not like oral listen-

ing”, ”The oral assessment because it is very stress-

ful and you do not have much time to think”, ” Oral

test because the student does not have enough time

to think about the answers”, ”Practical assessment

in a short time, because it does not assess logic but

speed”. A large group mentions the theoretical ex-

amination, some students just mention it without ad-

ditional explanations: ”Theory exams”, while others

provide a more detailed reasoning: evaluation of theo-

retical knowledge, because not all information is use-

ful in practice, or used, other claim that testing the

assimilation of theoretical notions it is shifting the fo-

cus from the actual learning of the subject to some

information that will be forgotten in a short time. The

percentages can be visualized in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Reasons for worst forms of evaluations methods

in student’s opinions.

In conclusion, students prefer practical examina-

tion and written examination, but not when it involves

writing programs on a piece of paper. Oral examina-

tion is considered by far the worst method of evalu-

ation due to induced stress and lack of time. Also,

a large group does not like theoretical exams that re-

quire information that is not useful in the long run.

3.4 Q3 - What Do Students Think Are

the Most Effective Ways to Learn?

This set of participants has special characteristics:

students spend two years in high school in the COVID

19 pandemic, where most of the learning activities

were online. Their exposure to online learning and

courses has given them an extended experience over

previous generations, so a high percentage, around

30% of students mentioned it as an effective learning

method. However, face-to-face was still the preferred

learning method, scoring more than 50% in student

options. Programming in pairs, group learning, indi-

vidual work, or practical problems also scored high in

student’s options as can be seen in Figure 6. As a re-

mark, some students mentioned more than one learn-

ing method: ”Different online tutorials, face-to-face

teaching and consulting the opinions of colleagues”,

so the sum of percentages exceeds 100%.

Figure 6: Most effective learning methods in student’s opin-

ions.

The Perceived Learning Behaviors and Assessment Techniques of First-Year Students in Computer Science: An Empirical Study

409

Some students did not provide reasons for their

learning preferences: ”Different online tutorials,

face-to-face teaching and consulting the opinions of

colleagues”, ”face-to-face teaching, study groups”,

”Online courses and programming (learning) with a

group of friends”. Others provided a detailed reason-

ing for their choice: ”Doing homework alone. Be-

fore doing my homework, I study the subject and then

apply the learned things to the problems. I notice

that the information settles very well in this way, not

only in this course. Another good method of learning

would be to teach a colleague / explain to someone

who does not understand.” Learning by exercise is

another method mentioned by students: ”for me the

best way of learning is practice. By doing many exer-

cises, I learn much easier”.

In conclusion, face-to-face learning is in the stu-

dent’s opinions the most effective learning method,

followed by learning using exercises, group learning,

and programming in pairs. So even for a generation

that has extensive experience with online learning,

they still prefer face-to-face learning,

4 TREATS TO VALIDITY?

Through the verification and application of commu-

nity standards as described in (Ralph, Paul (ed.),

2021), we attempted to reduce potential risks and ad-

dressed the validity threats mentioned in software en-

gineering research (Ralph, Paul (ed.), 2021). We con-

sidered the following possible threats: construct va-

lidity, internal validity, and external validity.

The target participant set, participant selection,

dropout contingency measures, and author biases

were among the issues we focused on for internal va-

lidity.

Selection and Participant Set. We selected for

the set of participants students who were enrolled in

classes taught by one of the study’s authors, chosen at

random.

Ethical Concerns. Before all students received the

survey link, we informed them that participation was

anonymous and voluntary. We also presented the

scope of the research and how the collected data will

be used.

Rates of Dropouts. We had few options to increase

participation in the study, as we were restricted by its

voluntary nature. The only influence on the participa-

tion of the students in the study was to ensure that they

understood the purpose of the survey. In addition, in

an attempt to boost participation, we kept the survey

open for two weeks and translated the questions into

the students’ native tongue.

Author Subjectivity. We have taken measures to ad-

dress the possibility of subjectivity in our data pro-

cessing methodology. Following suggested data pro-

cessing procedures, we as authors made sure that our

work was cross-validated by examining each other’s

contributions.

External Validity. We examine the possibility of ex-

tending and applying the study findings to the IT sec-

tor. The general research topic of the study is related

to industry and the difficulties that various teams face

when developing their human resources. We can con-

clude that the results of the study are useful to the

local IT industry due to the topic.

Validity of the Construction. We examined the sur-

veys’ questions for coherence, relevance, and perti-

nence. We developed the set of questions in three

stages: first, a set of questions was proposed by the

authors. All authors discussed and examined the

questions to increase clarity. Only a subset of the

questions that were most relevant to our study were

chosen to be included in the survey (second step). In

the final step, we verified the questions and decided

which questions were required and which were op-

tional. After these procedures were completed, we

created and distributed the survey to the participants.

Since the data were gathered anonymously, the au-

thors were unaware of the identities of the respon-

dents.

5 DISCUSSIONS

Upon examination of the data, we found that the stu-

dents primarily attribute their learning to two things:

the course’s or the topics’ level of interest and utility.

Practical Aspects. There is a definite tendency to

value and adhere to practical and passionate aspects.

Students dislike mechanical learning or theoretical

examinations where they are ”asked to know infor-

mation without use” or where they ”will later forget.”

This tendency toward practical aspects is reinforced

through answers to other questions. For example,

their preference for projects or continuous evaluation

are different aspects of the same disposition.

An intriguing feature about the students’ view on

evaluation is the absence of opinions regarding its

fairness; preferences are solely based on stress, pref-

erences, workload, and practicability.

Fear and Stress. Numerous students indicated that

the evaluation results were significantly impacted by

their ability to control their emotions and stress. Stu-

dents believe that oral evaluations are the worst due to

stressful circumstances, time constraints, and teacher

discussion — all of which make it difficult for them

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

410

to handle. We have to ask ourselves after looking at

these results Are these signs of a more emotional gen-

eration? One more argument would be the fact that

some of them acknowledge, admit, and express that

they”are afraid”. Stress and fear are strong emotions

that can affect performance, attitude toward learning

in general, and school / university specifically. Fail-

ure in a sphere of accomplishment can be a challeng-

ing experience that elicits feelings of guilt and fear,

ranging from mild to severe conditions, such as aty-

chiophobia, which can affect an individual’s behav-

ior and performance (Atkinson, 1957). Fear of being

wrong, of being judged appears as a collateral reason

for written examination: ”because I can make mis-

takes without fear of being judged”.

Given that first-year students in the participant set

had recently completed their high school education,

these findings should raise concerns about the teach-

ing methods and attitudes of high school teachers.

Reluctance to Work. Some students stated that they

would prefer simpler courses that do not require a lot

of work or learning time and effort when asked for

the reasons why they do not learn. Although there are

certain factors that can make learning more difficult,

such as scheduling classes during challenging times

of the day, such as 6 to 8 p.m. or half past seven or

eight a.m., they should not have a significant effect

on learning. More future research can determine how

these factors affect learning. However, stating that the

time spent learning something new is too much could

be a reflection of a recent development: students’ un-

willingness to put in the necessary effort to learn.

Although the outcomes can serve as a guide for

future modifications to instructional strategies, stu-

dent preferences should not be the only factor con-

sidered. Their point of view should be regarded more

as a guide for determining the best means of motivat-

ing and constraining them in order to optimize their

academic performance.

For instance, it’s not always detrimental that a

large portion of students exhibit a fear of failing. Be-

cause they consider learning hard and fear failure, it

does not mean that we should simplify the learning

content. Much better would be to search for methods

to bias the natural tendency for anxious people to set

either extremely low or very high aspirations in favor

of the last, or to reduce the anxiety related to failure.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Our investigation of the students’ primary motivations

to acquire knowledge reveals that the most crucial fac-

tors are the perceived usefulness of the learned infor-

mation and the level of interest in the course topics.

Although personal relationships with teachers were

found to be less influential, external factors, such as

excessive effort or time constraints, can negatively

impact the learning experience. These findings under-

score the importance of aligning educational content

with real-world applications and fostering student en-

gagement to improve motivation.

Students believe that in-person instruction is the

most effective way to learn, with exercise-based

learning, group instruction, and pair programming

coming in second and third.

Regarding the evaluation methods preferred by

students, our research indicates a preference for prac-

tical and written examinations. However, it should be

noted that the inclusion of writing programs on paper

is met with resistance. Oral examinations emerged as

the least favored method, attributed to induced stress

and perceived time constraints. Additionally, a sub-

stantial portion of students expressed dissatisfaction

with theoretical exams that they perceive as provid-

ing information that lacks practical utility in the long

run. These insights highlight the need for educators to

consider various assessment strategies that align with

students’ preferences and alleviate unnecessary stress.

Furthermore, our investigation of effective learn-

ing methods uncovered valuable information. The

emphasis on practical and applicable knowledge is

evident in students’ preferences for hands-on learn-

ing experiences. Our findings underscore the impor-

tance of incorporating real-world scenarios and en-

couraging interactive learning approaches. As edu-

cators and institutions strive to optimize the learning

process, understanding and integrating these prefer-

ences can contribute significantly to creating a more

effective and engaging educational environment.

In summary, our research provides valuable infor-

mation on the complex interplay of factors that in-

fluence students’ motivations, preferences in evalu-

ation methods, and effective learning strategies. By

acknowledging and incorporating these findings, ed-

ucators and educational institutions can foster a more

conducive learning environment that reflects the di-

verse needs and preferences of students, ultimately

enhancing the overall educational experience.

REFERENCES

Araque, F., Roldan, C., and Salguero, A. (2009). Factors

influencing university drop out rates. Computers &

Education, 53:563–574.

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-

taking behavior. Psychological review, 64(6p1):359.

The Perceived Learning Behaviors and Assessment Techniques of First-Year Students in Computer Science: An Empirical Study

411

Baquerizo, G. E. B., M

´

arquez, F. A. A., and Tobar, F. R. L.

(2020). La motivaci

´

on en la ense

˜

nanza en l

´

ınea. Re-

vista Conrado, 16(75):316–321.

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., and Terry, G. (2019).

Thematic Analysis, pages 843–860. Springer Singa-

pore.

Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies, N. (2015).

Dropout and completion in higher education in eu-

rope.

de Sousa, M. M., de Almeida, D. A. R., Mansur-Alves, M.,

and Huziwara, E. M. (2022). Characteristics and ef-

fects of entrepreneurship education programs: a sys-

tematic review. Trends in Psychology, pages 1–31.

George, M. L. (2020). Effective teaching and examination

strategies for undergraduate learning during covid-19

school restrictions. Journal of Educational Technol-

ogy Systems, 49(1):23–48.

Gutierrez-Aguilar, O., Talavera-Mendoza, F., Chica

˜

na-

Huanca, S., Cano-Villafuerte, S., and Sotillo-

Vel

´

asquez, J. A. (2023). E-learning and the factors

that influence the fear of failing an academic year in

the era of covid-19. Journal of Technology and Sci-

ence Education, 13(2):548–564.

Hazzan, O., Lapidot, T., and Ragonis, N. (2020). Guide to

teaching computer science. Springer.

Heublein, U., Ebert, J., Hutzsch, C., Isleib, S., K

¨

onig, R.,

Richter, J., and Woisch, A. (2017). Zwischen studi-

enerwartung und studienwirklichkeit. Ursachen des

Studienabbruchs, beruflicher Verbleib der Studienab-

brecherinnen und Studienabbrecher und Entwicklung

der Studienabbruchquote an deutschen Hochschulen.

Lemay, D. J., Doleck, T., and Bazelais, P. (2021). Transi-

tion to online teaching during the covid-19 pandemic.

Interactive Learning Environments, 31:2051 – 2062.

Liu, M., Gorgievski, M. J., Qi, J., and Paas, F. (2022).

Increasing teaching effectiveness in entrepreneurship

education: Course characteristics and student needs

differences. Learning and Individual Differences,

96:102147.

Martino, L. R. (1993). A goal-setting model for young

adolescent at-risk students. Middle School Journal,

24:19–22.

Motogna, S., Suciu, D., and Molnar, A.-J. (2021). Inves-

tigating student insight in software engineering team

projects. In Proceedings of the 16th International

Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to

Software Engineering - ENASE,, pages 362–371. IN-

STICC, SciTePress.

Neuwirth, L. S., Jovi

´

c, S., and Mukherji, B. R. (2021).

Reimagining higher education during and post-covid-

19: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Adult

and Continuing Education, 27(2):141–156.

Norem, J. K. and Cantor, N. E. (1986). Defensive pes-

simism: harnessing anxiety as motivation. Journal of

personality and social psychology, 51 6:1208–17.

Petrescu, M. and Motogna, S. (2023). A perspective from

large vs small companies adoption of agile method-

ologies. In Proceedings of the 18th International

Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to

Software Engineering - ENASE, pages 265–272. IN-

STICC, SciTePress.

Petrescu, M.-A., Pop, E.-L., and Tudor-Dan Mihoc (2023).

Students’ interest in knowledge acquisition in ar-

tificial intelligence. Procedia Computer Science,

225:1028–1036. 27th International Conference on

Knowledge Based and Intelligent Information and En-

gineering Sytems (KES 2023).

Ralph, Paul (ed.) (2021). ACM Sigsoft Empirical Standards

for Software Engineering Research, version 0.2.0.

Salas, R. P. (2017). Teaching entrepreneurship in computer

science: Lessons learned. In 2017 IEEE Frontiers in

Education Conference (FIE), pages 1-7. IEEE.

Seikkula-Leino, J., Oikkonen, E., Ik

¨

avalko, M., Kolhinen,

J., and Rytkola, T. (2010). Promoting entrepreneur-

ship education: The role of the teacher? Education +

Training, 52:117–127.

Sobral, S. (2020). Online teaching principles. In Erasmus

Teaching Week (HMU).

Vegliante, R., Miranda, S., and De Angelis, M. (2018). On-

line evaluation in the massive courses. In 11th annual

International Conference of Education, Research and

Innovation, pages 8214–8220.

Wang, S., Bajwa, N. P., Tong, R., and Kelly, H. (2021).

Transitioning to online teaching. Radical Solutions

for Education in a Crisis Context: COVID-19 as an

Opportunity for Global Learning, pages 177–188.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

412