A Community-Based Support Scheme to Promote Learning Mobility:

Practices in Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Japan

Rika Ikeda

a

, Andrey Ferriyan, Keiko Okawa and Achmad Husni Thamrin

Keio University, 2-15-45, Mita, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords:

Learning Mobility, Communities of Practice, Landscape of Practice, Micro-credentials, Open Badges,

e-portfolio, Higher Education, Southeast Asia, Japan.

Abstract:

Learning mobility enhances employability and expands career networks. Despite easy access to global knowl-

edge and skills through online and short-term learning mobility programs, learning fragmentation and inco-

herence have become issues. This research proposes a new scheme called Inxignia, which aims to enable

learners to achieve coherent learning continuity within or outside of School on the Internet Asia (SOI Asia),

an inter-university network in Southeast Asia and Japan, and increase a sense of community. Inxignia inte-

grates the three modes, namely (1) Engagement: Engaging with Communities of Practices within or connected

to SOI Asia; (2) Imagination: reflecting on experiences and small-scale learning achievements in SOI Asia;

and (3) Alignment: Coordinating with SOI Asia stakeholders to achieve the desired learning and career path.

A micro-credentialing e-portfolio platform supports enhancing each mode such as a feature to support reflec-

tion and plan learning from a bird’s eye view and open badges to visualize past journeys and future potential.

The implementation results indicated that Inxignia supported Imagination and Alignment modes for SOI Asia

Learners and the importance of including young faculty to make the scheme autonomous and sustainable.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Research Background

Learning Mobility is defined as the mobility of learn-

ers transnationally, regionally, or online, undertaken

for a specific period, organized for educational pur-

poses (EU, 2023), and a learning experience where

individuals move from their everyday context (LLLP,

2016). It includes summer programs and Massive

Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Learning Mobility

enhances employability and career networks (Bran-

denburg et al., 2014)(Babcock, 2012). Today, people

can easily acquire knowledge and skills and connect

with people worldwide through online and short-term

learning mobility programs (Brown et al., 2021) (De-

vlin et al., 2017). Although people can accumulate

knowledge, skills, and experiences, the challenge is

that the learning is short and different from the every-

day context. Therefore, it will need more continuity

with future learning and professional pursuits (van der

Hijden and Martin, 2023). In a rapidly changing so-

ciety, it is crucial to continue learning and acquiring

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-2491-5903

new skills through accumulating small-scale learning

offered in different locations and disciplines (Brown

et al., 2021). They also have the potential to pro-

vide education and training opportunities to a broader

range of learners, including disadvantaged and vul-

nerable groups (EU, 2022). Therefore, it is crucial to

solve the fragmentation and incoherence of learning.

A Landscape of Practice (LoP) offers a framework

to integrate learning outcomes from different commu-

nities for future learning and careers (Wenger-Trayner

et al., 2014). It comprises three modes: Engage-

ment, Imagination, and Alignment. Engagement is

participation in activities of Communities of Practice

(CoPs), not just memorizing knowledge one way on-

line or only in school. Imagination is using our imag-

ination to understand our current position and pos-

sibilities. Alignment is coordinating stakeholders to

achieve desired effects in the real world. Comprehen-

sive learning outcomes can incorporate even short-

term learning experiences through different modes.

1.2 Experimental Field

Inter-university networks play a crucial role in learn-

ing mobility. They offer joint educational programs

404

Ikeda, R., Ferriyan, A., Okawa, K. and Thamrin, A.

A Community-Based Support Scheme to Promote Learning Mobility: Practices in Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Japan.

DOI: 10.5220/0012679600003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 404-411

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

and credit transfers among partner universities, fund-

ing for study abroad, and collaborative research.

Inter-university networks exist in various fields and

sizes, depending on their objectives.

The research is conducted in SOI Asia (School

on the Internet Asia), an inter-university network in

Southeast Asia and Japan (Figure 1). Twenty-four

universities from twelve countries join this network.

Figure 1: Map of SOI Asia partner universities.

SOI Asia offers learning mobility programs in col-

laboration with partner universities, such as the Asia

Pacific Internet Engineer (APIE) program, to build In-

ternet Engineering skills, knowledge, and community

(SOI-Asia, 2016) (Arima et al., 2023). These pro-

grams combine in-person and online activities over

a few months or weeks and provide opportunities to

connect with communities in the region. APIE con-

sists of self-paced online courses, synchronous online

sessions, an on-site camp, and an internship. The pro-

gram begins with the self-paced online courses on Fu-

tureLearn, an online education platform, and the syn-

chronous online sessions held fortnightly. After fin-

ishing these components, participants can apply for

the on-site camp. The camp is held in various loca-

tions based on which partner university becomes the

host. This one-week training program teaches partic-

ipants how to independently deploy enterprise-level

networks, providing them with practical and valuable

knowledge. The internship is available for candidates

who have completed all other program components

in collaboration with relevant communities. Around

300 undergraduate and graduate students from partner

universities in seven countries and various disciplines

applied to the course in the latest batch in 2023.

During the interviews with a director of SOI Asia

and one advisory board member, they stated that the

community’s objective is to provide programs en-

abling all competent cyberspace engineers in each

country and economy to collaborate. This collabora-

tion will enable them to interact with people beyond

network engineers and work together to solve social

issues in the future.

1.3 Preliminary Research

The research takes the APIE program as an exam-

ple to understand the situation in SOI Asia through

the lens of the LoP framework. The research found

that SOI Asia has a strong Engagement mode due

to the opportunity to interact with peers, faculty, and

working professionals from diverse backgrounds with

a shared interest in internet engineering. An online

survey of the 28 participants in APIE indicates high

Engagement levels. The survey used a five-grade

evaluation, and respondents chose from Strongly Dis-

agree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, and Strongly Agree

for questions related to rating on Engagement. The

survey includes eight questions. More than 90 per-

cent of respondents agree or strongly agree that they

could confidently explain to others the objective and

content of the APIE program. Also, they are will-

ing to be more involved in the APIE community by

participating in internships and as teaching assistants.

More than 86 percent of respondents answered that

the most significant impact on their motivation is hav-

ing a clear idea of how they can utilize the experience

for their future learning and career or enjoyment of

the learning process. During the in-depth interview,

respondents who chose either of these answers high-

lighted that it was greatly influenced by the ability to

meet and interact with people from different contexts

and professionals in the field.

However, for Imagination and Alignment, the

results of the interviews and observation indicated

a need to support learners in navigating these two

modes. Even though interacting with faculty and

working professionals gave them a clearer idea of

their career possibilities, they need opportunities to

imagine where they stand and the next step to achieve

their career image after the program. Some students

mentioned that they did not know what to learn next

after the program ended, and they returned to their

daily lives. Furthermore, if they do, there is no op-

portunity to communicate their needs to the other

stakeholders to realize the step. The online survey

evaluated the Sense of Community with ten APIE

camp participants using The Brief Sense of Commu-

nity Scale (BSCS)(Peterson et al., 2008). The BSCS

was designed to assess the dimensions of Needs Ful-

fillment, Group Membership, Influence, and Emo-

tional Connection by using a 5-point Likert-type re-

sponse option format ranging from strongly agree to

disagree strongly. It has nine questions and 2-3 ques-

tions for each dimension. Although there were only a

few samples available, they provided interesting in-

A Community-Based Support Scheme to Promote Learning Mobility: Practices in Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Japan

405

sights. As a result, all ten students selected either

Agree or Strongly Agree for all dimensions except

for Influence. In contrast, they chose Strongly Dis-

agree, Disagree, or Neutral for the questions related

to Influence, a sense of mattering, of making a differ-

ence to a group. It is strongly related to the Align-

ment mode. The average for the Influence question

was 3.75, while the average for the other dimensions

ranged from 4.4 to 4.5. In in-depth interviews, one re-

spondent mentioned they did not have an opportunity

to communicate their needs to stakeholders. Lack of

Imagination and Alignment modes may prevent them

from further Engagement in the community, and from

developing a sense of community to SOI Asia related

to SOI Asia’s objective mentioned in 1.3.

SOI Asia is also challenged by the gap in learn-

ing and career opportunities among universities. In

an interview with a partner university from Indone-

sia, one faculty member said that his university is lo-

cated in an area that is not as central as the univer-

sities in Jakarta, and companies do not recognize the

quality of the students. Suppose we create an environ-

ment where smaller-scale learning mobility programs

lead to continued consistent learning and further in-

volvement in the community. In that case, it can solve

this opportunity gap by increasing their employabil-

ity and career network. This research aims to design

a scheme integrating three modes defined by the LoP

framework for learners to encourage coherent learn-

ing continuity within or outside of SOI Asia and a

sense of community in SOI Asia. Quantitative and

qualitative evaluation was used to validate the impact

of the delivery method.

Next, a literature review explored the LoP frame-

work and the possibilities of designing Imagination

and Alignment modes that are lacking in SOI Asia.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Communities of Practice and

Landscape of Practice

Lave and Wenger define learning as a participation

process in a Community of Practice (CoP). A CoP

is a group of people who share a common concern,

problem, or interest and come together to fulfill in-

dividual and group goals. The Landscape of Prac-

tice (LoP) concept compares participation in mul-

tiple CoPs to a landscape and that learning is the

path one follows in that landscape. The learning

outcome is the identity formed while traversing this

landscape(Wenger-Trayner et al., 2014). The follow-

ing are modes for building identity in LoP (Wenger-

Trayner et al., 2014)(Morimoto et al., 2014)(de Nooi-

jer et al., 2022):

• Engagement. To participate in an activity by

working or talking with people in the CoPs.

• Imagination. Using our imagination to situate

ourselves in the world, identify different ways of

thinking, reflect on our situation, and search for

new possibilities.

• Alignment. A two-way process of adjusting per-

spectives, interpretations, and contexts so that ac-

tions have the expected effects.

Wenger notes that while these modes of identifi-

cation are distinct, they are the most effective in com-

bination (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2014).

A few practical studies still have yet to be con-

ducted in the context of inter-university networks.

Therefore, this research can contribute to validating

this framework in that aspect.

2.2 Reflection Method for Learning

In the context of SOI Asia, Imagination is reflect-

ing on experiences, including small-scale learning, to

imagine where they stand and future learning and ca-

reer possibilities. E-portfolio is a tool accepted and

used for reflection in education (Hamdan and Yassine-

Hamdan, 2022). It is also used to plan for the fu-

ture (Morimoto et al., 2014). An E-portfolio is elec-

tronic data that continuously accumulates all possi-

ble learning evidence to utilize it to promote learning

and career development (Wiedmer, 1998)(Morimoto

et al., 2014). The emergence of an e-portfolio, an

electronic or digital portfolio, in the mid-1990s con-

stituted a small step within the school reform agenda

and teacher accountability, where learners construct,

articulate, and assess their learning. Thus, using an e-

portfolio, students respond to challenges in preparing

critical thinkers who participate in the learning pro-

cess rather than act as passive recipients (Hamdan and

Yassine-Hamdan, 2022). Also, building structured

opportunities, such as using e-portfolios to reflect and

integrate learning, can improve students’ ability to re-

flect better (Hj. Ebil et al., 2020). However, they con-

tain a large amount of information, making them less

likely to be reviewed on an ongoing and overarching

basis. There is a need for other approaches to lifelong

learning that combine learning offered in different lo-

cations and disciplines.

Life storytelling is an act of telling one’s life story

as a reflection method and an action performed to

understand oneself and the world (Trentham, 2007).

This reflection method is used in e-portfolios as

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

406

well. For example, Kanazawa Institute of Technol-

ogy provides an e-portfolio where students register

their life history (KIT, 2017). Arima proposed the

Life-storytelling Board, a tool designed to be con-

sistent in life-storytelling, creating opportunities for

continuous and overarching reflection on life (Arima,

2021). Combining blocks with keywords related to

the episode of the user’s life supports continuous re-

flection on the whole life and its relationships with-

out information overload with text. Specifically, the

speaker and listener interact and write the speaker’s

experiences and memories - episodes - in hexagonal

blocks called episodic blocks. This process connects

the individual episodes to the episodic block, an On-

tological Metaphor. An Ontological metaphor is a

metaphor whereby abstract, unwieldy, or fuzzy con-

cepts are viewed as objects with human scale and in-

teraction potential (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). This

process transforms abstract and ambiguous episodes

into a handleable form. These episodic blocks will

download episodes onto the physical or online space,

thus reducing the cognitive load on the brain. Mul-

tiple episodic blocks can be combined, divided, and

arbitrarily placed in physical or online space to bring

meaning to the relationships between episodic blocks.

2.3 Co-Design of Learning in Multiple

Stakeholders

Alignment within the context of SOI Asia means co-

ordinating with stakeholders to achieve the desired

learning and career pathways. Co-Design is one of

customer co-creation, and it allows a design team to

combine two sets of knowledge that are key to ser-

vice design: Customer insights into latent user needs

and in-house professionals’ conversion of promising

new ideas into viable concepts (Trischler et al., 2018).

Co-Design allows selected customers or users to be-

come part of the design team as experts in their ex-

periences. By actively involving customers in the in-

novation process, the firm can overcome the problem

of user needs being sticky, difficult to transfer, and ar-

ticulate (Von Hippel, 2001) (Witell et al., 2011). The

involvement of key users through Co-Design during

the ideation stage of a service design process can lead

to the development of design concepts with more sig-

nificant user benefit than a team composed solely of

in-house experts (Trischler et al., 2018).

Micro-credentials can be used to create a learn-

ing pathway by combining various forms of learning

opportunities by different entities. Micro-credentials

certify learning outcomes acquired in much smaller

learning modules than a traditional degree. Its role

makes learning outcomes visible and provides a com-

mon language within the communities while simulta-

neously resolving fragmentation of small-scale learn-

ing (Yonezawa, 2020). Micro-credentials are of-

ten provided as Open Badges, digital representations

of credentials as digital badges that contain meta-

data about learning achievements such as informa-

tion on the issuer, the badge criteria, and so on (IMS,

2020). There are micro-credential services that pro-

vide the ability to create, issue, collect, and share

Open Badges, such as Credly. The services also pro-

vide a Learning Pathway function that combines dif-

ferent badges to visualize learning pathways available

for learners. Companies, universities, and educational

institutions are increasingly adopting those services.

2.4 Summary

The literature review indicates that the LoP provides

a framework for considering solutions to fragmen-

tation and incoherence of learning. Specifically, to

integrate learning from different CoPs as identity =

learning outcomes, it is crucial to navigate through

three modes: Engagement, Imagination, and Align-

ment. While SOI Asia supports Engagement, the need

for help in Imagination and Alignment was suggested

based on the preliminary research.

A further literature review was conducted to de-

sign methods for Imagination and Alignment in SOI

Asia. Regarding Imagination, the literature review

suggested that e-portfolios can effectively encour-

age reflection. The Life-storytelling Board allows

for visual, comprehensive, and ongoing reflection on

life-extended learning in different CoPs. Regarding

Alignment, it indicates that involving learners and

experts, such as faculty members and working pro-

fessionals, in designing learning pathways makes it

easier to incorporate learners’ needs. Additionally,

micro-credentials make learning outcomes visible and

provide a common language for various educational

programs offered by different organizations. There-

fore, it is suitable for visualizing learning opportuni-

ties from different organizations, bringing them to-

gether as a single learning path, and continuously

editing them.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

This research proposes Inxignia: A community-based

scheme to promote learning mobility. It consists of

the process that supports learners in navigating three

modes defined based on the LoP framework and a

micro-credentialing e-portfolio platform to enhance

each mode. Three SOI Asia community members join

A Community-Based Support Scheme to Promote Learning Mobility: Practices in Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Japan

407

the scheme proposed in this research: Learners who

are current or former students of the partner univer-

sities, faculty from SOI Asia partner universities, and

working professionals who are experts with several

years of experience in industries, governments, and

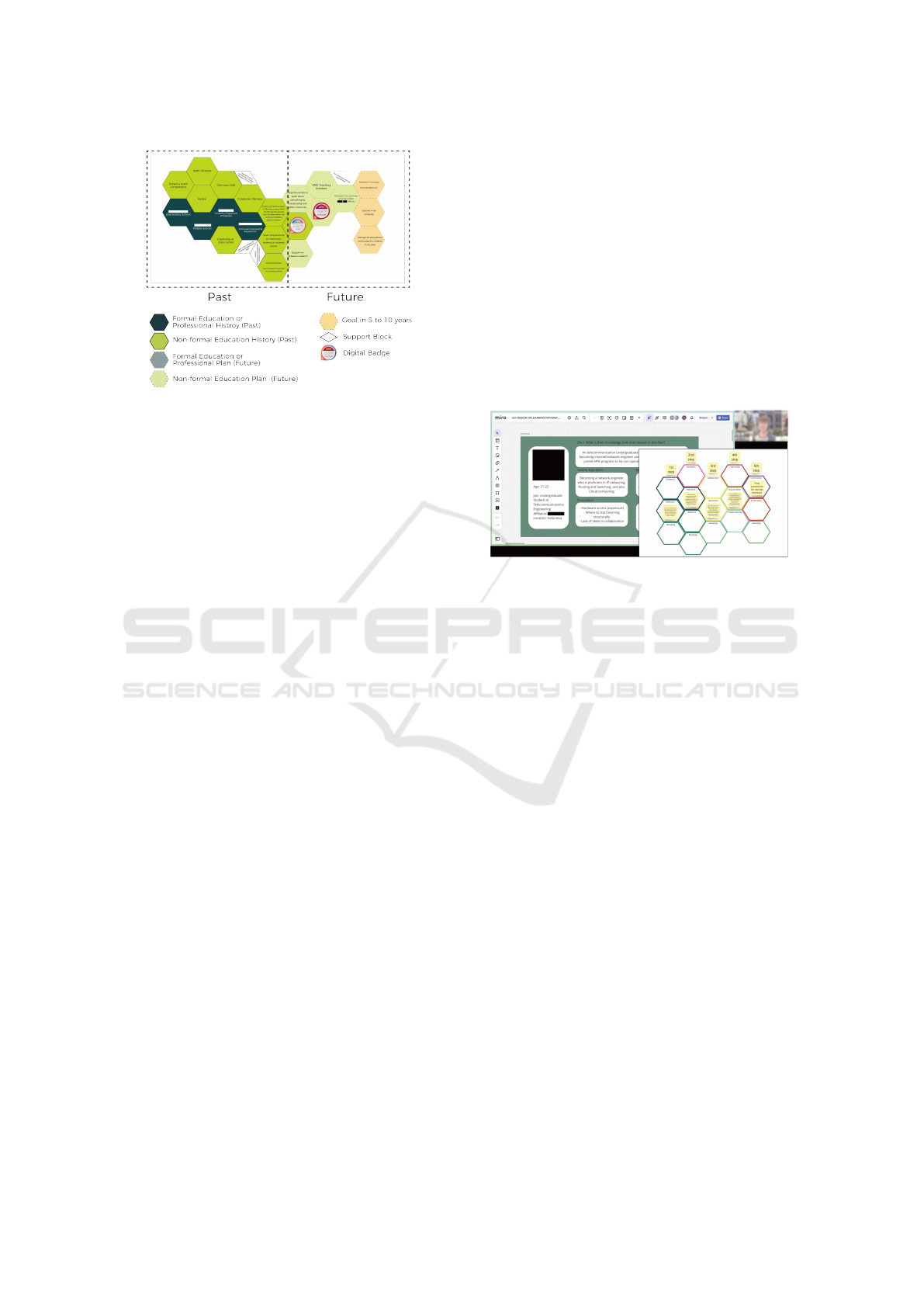

international organizations. Figure 2 gives a whole

picture of Inxignia. The utilization of technology en-

hances each mode, such as e-portfolios for tracking

learning journeys and learners’ spontaneous reflection

and the open badge to provide a common language to

design learning with multiple stakeholders.

Figure 2: Inxignia Scheme.

In addition to the features of other micro-

credentialing services, the platform offers the Life-

storytelling Board. The platform will be updated

to integrate and manage micro-credential data from

other sources so learners can utilize them for each

process. The platform uses an Open-Badge to main-

tain compatibility with other micro-credential sys-

tems and works on adaptation with version 3.0. It

unifies the information to be included in Open-Badge

with other micro-credential services. Quality assur-

ance standards will also be aligned in the future.

In the Engagement mode, learners engage with

CoPs within or connected to SOI Asia through learn-

ing mobility programs. The Faculty designed and

delivered the programs involving Working Profes-

sionals’ interaction with learners through lecturers

and other forms. To motivate the further participa-

tion of learners, recognition of small achievements

in the form of open badges is issued and stored on

the platform. Visualizing and collecting their learn-

ing achievements into a single platform is also ex-

pected to foster a sense of community across time and

place. In the Imagination mode, learners use the life-

storytelling board to reflect and imagine where they

stand and their future possibilities. Then, through the

Learning Pathway Codesign workshop, learners col-

laborate with faculties and working professionals to

design their subsequent learning (Alignment mode).

Participants can utilize existing learning opportunities

to create the learning pathway and create new oppor-

tunities. Combined with the open badge to visualize

learning opportunities in the community. It will be-

come a new credential if new learning opportunities

are implemented. Lastly, community involvement is

necessary to implement the ideas from the workshop

and connect them to re-engagement.

This research is divided into three phases.

• Phase 1. Design Imagination component for

Learners can imagine how they can connect the

learning experience to the subsequent learning

and career.

• Phase 2. Design Alignment component so Learn-

ers can communicate their needs to stakeholders.

• Phase 3. Integrate the scheme into the community

to make it sustainable.

This paper reports on the results of Phase 1 and 2, and

the progress of Phase 3.

4 IMPLEMENTATION

4.1 Phase 1. Life-Storytelling Board

This research proposes a Life-storytelling Board to

facilitate the Imagination mode. Unlike the original

Life-storytelling Board, design an online version to

be added as a platform feature. Figure 3 shows an ex-

ample of a completed board and the components to

create the board.

To create the board, two or three Learners are

paired up and divided into a speaker and a listener,

and the speaker describes their formal and non-formal

educational and professional history. Those keywords

are written in a block and placed on the board. Each

block of formal and non-formal educational history is

color-coded. After placing the blocks about the past,

the speaker set a goal in 5-10 years and considered the

steps to bridge that goal and the present while placing

the transparent blocks. Any comments or ideas they

want to add should be noted and placed in the support

block. The listener looks at the blocks and asks the

speaker questions, digging deeper into past and fu-

ture stories and offering ideas. When they reflect on

the past and plan the future, they can place the digital

badges they earned and plan to get on the block, to

visualize the correlation.

Pre- and post-online surveys were conducted to

see changes before and after the experiment. A 5-

point Likert Scale, from Strongly Disagree to Agree

Strongly, was used in the survey to avoid the extremes

of yes/no answers and to understand the nuances of

the answers. We asked twelve questions for each of

the pre- and post-surveys. Interviews were also con-

ducted to dig deep into the survey responses.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

408

Figure 3: An Example of Life-storytelling Board and the

Components (Ikeda et al., 2023).

The Life-storytelling Board was implemented

with 27 students in APIE. This time, we used a vi-

sual collaboration platform, as a prototype. When

asked if they had a clear idea of how APIE could be

used in the long or short term, some respondents an-

swered Neutral or Disagree before the test, and all

responded Strongly Agree or Agree after they cre-

ated the Life-storytelling Boards. The overall aver-

age also improved from 4.22 to 4.63. One respondent

mentioned that he was able to come up with specific

steps to take. In addition, seventeen speakers who did

not state plans to utilize APIE in the pre-survey men-

tioned ideas for the future to take advantage of APIE

opportunities, such as participating in an APIE Intern-

ship and getting deeper involvement with the APIE

community after creating the Life-storytelling Board.

Some also suggested that they could use the contacts

they made at the APIE to hold workshops on their

own campuses to share the knowledge they gained

from the APIE. It indicated that the Life-storytelling

Board prompted using the opportunities available in-

side and outside of SOI Asia to leverage the experi-

ence of participating in APIE. One student said this

helps because he can see the big picture and how each

block supports the other. Another said he thinks the

most important thing is to see the connections, and

looking back at the past and future trends made it clear

what he is more interested in.

4.2 Phase 2. Learning Pathway

Co-Design Workshop

This research proposes the Learning Pathway Co-

design Workshop to support the Alignment mode. In

the workshop, stakeholders discuss designing a learn-

ing pathway while involving learners as the experts of

their experiences.

We ran three trials with a total of 33 participants

and refined the workshop based on observations and

feedback. The final trial separated the learners’ and

faculties’/working professionals’ sessions to facilitate

comfortable communication. Learners develop fic-

tional characters called personas based on their cur-

rent situation. Faculty and working professionals de-

fine the image of human resources they want to de-

velop and create corresponding learning pathways us-

ing pre-defined learning activities (Figure 4). Af-

ter faculty and working professionals create learning

pathways, students provide feedback. Interviews and

observations are conducted to assess if the Alignment

mode is supported.

Figure 4: Learning Pathway Co-design Workshop and the

Learning Pathway created.

The third trial was implemented online with three

learners and four faculty members involved in the

APIE program. They created subsequent learning

pathways after the APIE program. This workshop

took 90 minutes. The interviews and observation

showed that the workshop enabled faculty members to

understand learners’ needs and discuss how it can be

realized. One faculty member mentioned that learn-

ing design is traditionally faculty and government-

centric in her country, and this approach enables a

shift to student-centric. Two faculty members men-

tioned that the persona defined by learners supported

understanding their needs. Another faculty said that

vague ideas in his head became more concrete and

realistic. Also, young faculty members actively led

discussions, expressing interest in implementing the

learning pathway at their campuses. One young fac-

ulty mentioned that if this proves successful, he wants

to duplicate it at other universities. Students also

spoke up more and showed interest in participating

in the learning pathway. However, one student high-

lighted the lack of real-time exchange with faculty.

This affects the sense of community. Therefore, the

final scheme needs to be improved.

A Community-Based Support Scheme to Promote Learning Mobility: Practices in Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Japan

409

4.3 Phase 3. Community Integration

For the scheme to work well within a community, it

is necessary to ascertain how the new initiatives work

and create a scheme based on that. In the APIE Pro-

gram, two instances where learning opportunities ini-

tiated by partner universities emerged in Indonesia,

and interviews were conducted to investigate the fac-

tors contributing to this. The first instance was start-

ing study groups at one of the partner universities in

Indonesia after the APIE camp. This study group was

focused on more advanced topics related to the pro-

gram. The second instance was observed when a part-

ner university implemented a program that replicated

the content of the APIE camp.

The interview was conducted with four faculties,

three teaching assistants, and six students from the

partner universities. For the first instance, the study

group began when one of the faculty members knew

about the student’s learning progress in the APIE pro-

gram, which motivated him to support them in their

subsequent learning. Specifically, it was when he

heard that the students had completed their online

studies and would participate in the APIE camp in

Japan. The faculty member then approached other

faculty members he knew and enlisted their help.

However, there were challenges in continuing the

study group. Learners commented that the faculty

members who organized the study group were busy

and had been canceled several times. One of the

learners said he had tried conducting study groups but

could not start without getting instructions on what to

do.

The second case study was a partner university

implementing a program modeled after APIE. The

presence of young faculty and graduate students was

cited as a significant factor influencing the implemen-

tation of this program. Young faculty and graduate

students, who are the contacts of those who play a

central role as SOI Asia community members, led

the implementation of this program. Senior faculties

were involved as mentors to them in implementing the

programs or participated in the program as partial in-

structors or technical supporters. However, one of the

young faculty members mentioned that it would be

difficult for him to continue leading that program in

the future because of his schedule. On the other hand,

the doctoral student who became a Teaching Assis-

tant showed motivation to organize the APIE program

in the future. This suggested connecting the younger

generation to take the next lead.

The result indicates that building bridges between

students and the older generation of faculty and work-

ing professionals, including young faculty and gradu-

ate students, is essential to implementing the scheme

sustainably and smoothly in the SOI Asia community.

During the interview, the young faculty members and

graduate students involved in the second case men-

tioned that their motivation for participating was to

build relationships with other faculty members from

different campuses or countries and gain the neces-

sary skills for their careers, such as planning and im-

plementing educational programs. In addition, be-

cause the educational programs at SOI Asia also in-

volve corporations and international organizations as

stakeholders, it can be an opportunity to expand ca-

reer pathways outside academia. Applying these re-

sults to the community integration of the scheme,

young faculty and graduate students can play a role

in encouraging learners to conduct a Life-storytelling

Board for Imagination mode. In the Alignment mode,

they, with the mentorship of the older generation, will

be responsible for sharing learners’ progress, present-

ing ideas that emerge from the Learning Pathway Co-

design Workshop in regular meetings of the SOI Asia

community, and executing them.

5 CONCLUSION

This research proposes a community scheme called

Inxignia to address the fragmentation of small-scale

learning mobility programs. Designed based on En-

gagement, Imagination, and Alignment modes de-

fined by LoP, it was implemented in SOI Asia. The

research comprises three phases: the design of Imag-

ination and Alignment modes, and the community

scheme integration. In Phase 1, we designed the Life-

storytelling Board, which supported learners in imag-

ining how they could connect the learning experi-

ence to their subsequent learning and career. Phase

2 featured the Learning Pathway Co-design work-

shop to communicate learner needs to stakeholders.

Phase 3 emphasized involving the young generation

for scheme autonomy and sustainability in the com-

munity. The Life-storytelling Board and Learning

Pathway Co-design Workshop will be integrated into

the APIE program, led by young faculty and grad-

uate students as the next plan. They spearhead ac-

tivities such as encouraging learners to create a Life-

storytelling Board, conducting the Learning Pathway

Co-design Workshop, sharing workshop ideas with

the SOI Asia community, and leading discussions for

implementation in regular meetings. The following

items will be evaluated through online surveys, inter-

views, and observations with community members.

• What factors contributed to the implementation of

subsequent learning?

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

410

• What elements fostered the learning continuity of

learners within or outside the community?

• What aspects led to improving learners’ sense of

community?

• What circumstances played a role in the sustain-

ability of the scheme?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by SOI Asia. We express

our deepest gratitude to them for designing and im-

plementing learning mobility programs for university

students in Asia-Pacific and to all other institutions

and individuals who contributed to this research.

REFERENCES

Arima, S. (2021). Design of fermentational reflection

model. PhD thesis, Keio University Graduate School

of Media Design.

Arima, S., Maekawa, M. S., Kudo, N., and Okawa, K.

(2023). Design of a blended learning ict education

program for undergraduate students in asia-pacific

based on communities of practice. In Proceedings of

the 15th International Conference on Computer Sup-

ported Education.

Babcock, E. D. (2012). Mobility mentoring®. In Boston,

MA: Crittenton Women’s Union.

Brandenburg, U., Berghoff, S., and Taboadela, O. (2014).

The erasmus impact study. European Commission Ed-

ucation and Culture.

Brown, M., Mhichil, M. N. G., Beirne, E., and

Mac Lochlainn, C. (2021). The global micro-

credential landscape: Charting a new credential ecol-

ogy for lifelong learning. In Journal of Learning for

Development, volume 8, pages 228–254. ERIC.

de Nooijer, J., Dolmans, D. H., and Stalmeijer, R. E. (2022).

Applying landscapes of practice principles to the de-

sign of interprofessional education. In Teaching and

Learning in Medicine 2022, volume 34, pages 209–

214. Taylor & Francis.

Devlin, M., Kristensen, S., Krzaklewska, E., and Nico, M.

(2017). Learning mobility, social inclusion and non-

formal education: Access, processes and outcomes.

volume 22. Council of Europe.

EU (2022). Council recommendation on a european ap-

proach to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and

employability. pages 10–25.

EU (2023). European platform on learning mobil-

ity. https://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/youth-partnership/

european-platform-on-learning-mobility. Accessed:

2023 Dec 29.

Hamdan, S. M. and Yassine-Hamdan, N. (2022). eportfolio:

A tool of reflection and self-evaluation in teaching. In

THE GLOBAL eLEARNING JOURNAL, volume 9.

Hj. Ebil, S., Salleh, S. M., and Shahrill, M. (2020). The use

of eportfolio for self-reflection to promote learning:

A case of tvet students. In Education and Information

Technologies, volume 25, pages 5797–5814. Springer.

Ikeda, R., Ferriyan, A., Okawa, K., and Thamrin,

A. H. (2023). Enhancing learning mobility with

a community-based micro-credential e-portfolio plat-

form service for higher education. In European Con-

ference on Technology Enhanced Learning, pages

566–572. Springer.

IMS (2020). Ims open badges. https://openbadges.org/. Ac-

cessed: 2023 Dec 29.

KIT (2017). Kit portfolio system. https://www.kanazawa-it.

ac.jp/kyoiku/portfolio.html. Accessed: 2023 Dec 29.

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By.

University of Chicago Press.

LLLP (2016). Learning mobility for all. https://

lllplatform.eu/policy-areas/skills-and-qualifications/

learning-mobility-for-all/. Accessed: 2023 Dec 29.

Morimoto, Y., Nagata, T., Ogawa, K., and Yamakawa, O.

(2014). e-portfolio in education. In Education and

Information Technologies. Minervashobo.

Peterson, N. A., Speer, P. W., and McMillan, D. W. (2008).

Validation of a brief sense of community scale: Con-

firmation of the principal theory of sense of com-

munity. In Journal of Community Psychology, vol-

ume 36, pages 61–73. Wiley Online Library.

SOI-Asia (2016). School on internet asia. https://www.soi.

asia/. Accessed: 2023 Dec 29.

Trentham, B. (2007). Life storytelling, occupation, so-

cial participation and aging. In Occupational Therapy

Now, volume 9, pages 23–26.

Trischler, J., Pervan, S. J., Kelly, S. J., and Scott, D. R.

(2018). The value of codesign: The effect of cus-

tomer involvement in service design teams. In Journal

of Service Research, volume 21, pages 75–100. Sage

Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

van der Hijden, P. and Martin, M. (2023). Short courses,

micro-credentials, and flexible learning pathways: A

blueprint for policy development and action. In Policy

paper. International Institute for Educational Planning

Paris.

Von Hippel, E. (2001). User toolkits for innovation. In Jour-

nal of Product Innovation Management, volume 18,

pages 247–257. Wiley Online Library.

Wenger-Trayner, E., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Hutchinson, S.,

Kubiak, C., and Wenger-Trayner, B. (2014). Learning

in Landscapes of Practice: Boundaries, identity, and

knowledgeability in practice-based learning. Rout-

ledge, 1 edition.

Wiedmer, T. L. (1998). Digital portfolios. In Phi Delta

Kappan, volume 79, page 586. Phi Delta Kappa.

Witell, L., Kristensson, P., Gustafsson, A., and L

¨

ofgren, M.

(2011). Idea generation: customer co-creation ver-

sus traditional market research techniques. In Journal

of Service Management, volume 22, pages 140–159.

Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Yonezawa, A. (2020). Raising the issue of international ac-

ceptability of quality assurance. https://www.mext.go.

jp/content/20201125-mxt koutou01-1422495 04.pdf.

Accessed: 2023 Dec 29.

A Community-Based Support Scheme to Promote Learning Mobility: Practices in Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Japan

411