The Influences of Employees' Emotions on Their Cyber Security

Protection Motivation Behaviour: A Theoretical Framework

Abdulelah Alshammari

1

, Vladlena Benson

2

and Luciano Batista

2

1

Faculty of Economics and Administration, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

2

Operation and Information Management, Aston University, Aston Street, Birmingham, U.K.

Keywords: Cybersecurity, Positive Emotions, Negative Emotions, Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), Broaden and

Build Theory (BBT), Employees’ Protection Motivation Behaviour.

Abstract: At the employee level, cyber threats are a sensitive issue that requires further understanding. Cyber-attacks

can have a multifaceted impact on an organisation. Psychological research has demonstrated that emotions

influence individuals’ motivation to engage in cybersecurity protection behaviour. Most extant research

focuses on how external influences may affect employees’ cyber security behaviours (e.g., understanding risk,

rationality in policy decision-making, security regulations, compliance, ethical behaviour, etc.). Little

research has been done to date on how employees’ internal emotions affect their motivations for cybersecurity

protection. To bridge this gap, this paper aims to expand the research by establishing a model for measuring

the effect of employees’ negative and positive emotions on their cybersecurity protection motivation

behaviour. The model will emphasise self-efficacy as a mediating factor and cybersecurity awareness as a

moderating factor, and this model is based on a comprehensive evaluation of the existing literature. More

specifically, the proposed theoretical model was established by integrating the protection motivation theory

(PMT), and the broaden and build theory (BBT) to understand the effects of negative and positive emotions

on employees' cybersecurity protection motivation behaviour. This study opens the gates for future research

on the role of emotions on employees’ cybersecurity protection motivation behaviour. Furthermore,

understanding how emotions affect employees’ cybersecurity protection motivation will be a valuable

contribution to academia, helping decision-makers and professionals deal with the effects of emotions

regarding cybersecurity.

1 INTRODUCTION

Many confidential information and data are collected,

processed, stored, and transmitted over networks by

governments, organisations, financial institutions,

universities, and businesses. Globally, in 2023, 5.16

billion people are using the internet, representing

64.4% of the world’s population (DataReportal.,

2023). This population has become more vulnerable

to cyber-attacks due to this rapid growth rate. Cyber

activities by hacker groups, criminals, terrorists, and

state and non-state actors have also increased due to

civilisation’s reliance on the internet and information

technology (Spidalieri and Kern, 2014). As a result,

government agencies, as well as private and public

companies, have been attacked by cybercriminals.

Individuals and organisations are adversely affected

by cybersecurity attacks, financially and

psychologically, and in other ways (Liang et al.,

2019).

The argument on the range of human aspects of

cybersecurity has drawn the attention of many

researchers. Individual aspects of cybersecurity

influence cybersecurity decisions (Snyman et al.,

2018). For example, emotions and understanding risk

are considered human aspects of cyber security (Beris

et al., 2015), while McCormac et al. (2018) claim that

resilience and job stress are human. Other aspects

include emotional reactions to cybercrime (Liang et

al., 2019; Brands and Van Doorn, 2022), fear of

cybercrime (Jansen and van Schaik, 2018), rationality

in security policy decision-making (Bulgurcu et al.,

2010), compliance with security regulations and

ethical behaviour in cybersecurity (Spanaki et al.,

2019), consequences of avoiding technology due to

adverse incidences (Zamani and Pouloudi, 2021). The

role of emotions and emotion-related aspects is still

524

Alshammari, A., Benson, V. and Batista, L.

The Influences of Employees’ Emotions on Their Cyber Security Protection Motivation Behaviour: A Theoretical Framework.

DOI: 10.5220/0012681600003690

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024) - Volume 2, pages 524-531

ISBN: 978-989-758-692-7; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

developing in cybersecurity and security-related

behaviours (D’Arcy et al., 2014; Lowry and Moody,

2015; Boss et al., 2015).

The extant literature has neglected employees’

emotions about protecting information systems

resources against internal and external attacks.

Additionally, greater attention needs to be paid to the

organisations in stimulating negative and positive

emotions in employees when protecting their

information systems resources. According to Burns et

al. (2017), the behaviours of employees are closely

related to their psychological movement regarding

security. In the past, humans have been regarded as a

vulnerability in the field of cybersecurity (Benson &

McAlaney, 2019). Security challenges stemming

from employees' non-compliance have grown in

complexity and difficulty for modern firms, even

though many have implemented cybersecurity

policies (Anderson et al., 2017; Khan and AlShare,

2019). Prior research has primarily focused on

investigating the impact of different factors on

employees' adherence or non-adherence to

cybersecurity policies. These studies have drawn

upon theories from psychology, sociology, and

theoretical criminology (Cram et al., 2017). Few

studies have specifically examined the impact of

employees' emotions on their engagement in

protective security behaviours.

To bridge this gap in prior research, this paper

aims to expand our knowledge by establishing a

model for measuring the effects of employees’

emotions on their cybersecurity protection motivation

behaviour. The research underpins the PMT and the

BBT. Ifinedo (2012) posits that PMT is a crucial

framework elucidating an individual's intention to

participate in cybersecurity protection. It is utilised in

research on cybersecurity issues, specifically in the

context of safeguarding an organisation's information

assets. Nevertheless, the BBT posits that positive

emotions, such as enjoyment, interest, and

anticipation, expand an individual's consciousness

and stimulate innovative and exploratory thinking

and behaviours. However, negative emotions narrow

the focus of thoughts, although this does not indicate

a counter-association between positive and negative

emotions (Fredrickson and Branigan 2005). This

paper follows the Posey et al. (2013, 2015) definition

that protection motivation behaviour is actions taken

by individuals within an organisation to safeguard

both organisationally relevant information and the

computer-based information systems that store,

collect, share, and control that information from risks

related to cybersecurity.

To accomplish the research aim, the following

objectives have been set: (1) to identify whether

negative or positive emotions have a direct effect on

employees' cyber security protection motivation

behaviours; (2) to emphasise how self-efficacy may

contribute to cybersecurity protective motivation

behaviours by mediating the effects of these emotions;

(3) to examine how cybersecurity awareness modifies

the association between employees' self-efficacy,

protective motivation behaviours, and positive and

negative emotions. Moreover, these objectives make

valuable contributions to academia in various

dimensions. Additionally, it presents an advanced

theoretical framework for examining emotions.

Furthermore, it assists decision-makers and experts in

managing the impact of emotions about cybersecurity.

This is because there is a lack of published papers that

attempt to establish a conceptual framework using

PMT and BBT to measure negative and positive

emotions related to employee protection motivation

behaviour.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

2.1 Protection Motivation Theory

(PMT)

The development of PMT was prompted by the need

to predict behavioural change using fear appeals,

which is part of persuasive communication (Rogers,

1975, 1983). According to Ifinedo (2012), PMT is a

critical theory that explains an individual’s intent to

engage in cybersecurity protection. It is employed in

studies of cybersecurity problems where workers

must protect an organisation’s information assets,

because it focuses on developing protective

behaviours when dealing with personal health threats

(Boss et al., 2015). Rogers (1975) developed the PMT

approach by introducing three independent stimulus

variables. Perceived efficacy, perceived security

threats, and perceived susceptibility are the basis of

the cognitive meditational process. Consequently,

perceptions impact protection motivation, which is

synonymous with behavioural intentions (Rogers,

1983). Self-efficacy refers to the belief that

individuals can perform a suggested response.

Reflecting on the applications of PMT in

cybersecurity, threat appraisal encompasses the

potential vulnerability of cyber-attacks and the

severity of the latter. This appraisal includes ways for

employees to assess their strengths and ability to avert

The Influences of Employees’ Emotions on Their Cyber Security Protection Motivation Behaviour: A Theoretical Framework

525

potential losses from threats (Woon et al., 2005). It

deals with how individual employees can assess the

damage resulting from cybercrimes. In a coping

appraisal, there is a mixture of reaction and self-

efficacy. An individual’s confidence plays an active

role in averting cyber-attacks.

Employees can determine whether or not the

threat is mild and whether they should wait for expert

assistance rather than become involved in the

aversion process (Herath and Rao, 2009). The PMT

has been employed in cybersecurity research to find

connections between preventive behaviour, well-

being, and computer security issues. It has

successfully explained the security behaviours in

various cybersecurity applications within an

institutional environment (e.g., Burns et al., 2017;

Zhen et al., 2020; Burns et al., 2019).

2.2 Broad and Build Theory (BBT)

Emotions play a significant role in human behaviour

(Fredrickson, 2004). Positive emotions are believed

to increase actions and thoughts in this theory. This

means they increase opportunities to consider the

many factors logically with situational responses and

consequently promote adaptive reactions to the

environment. The broadening sets the stage for

allocating the resources necessary to promote

complete well-being. Positive emotions indicate not

only current well-being but also enhance future well-

being. Well-being is facilitated by the building of

resources, which results in flourishing. Positive

emotions facilitate the expression of thoughts and

actions, whereas negative emotions limit coping

resources (Fredrickson, 2001).

The BBT states that resilient individuals can use

constructive coping methods more often, thus

generating positive emotions (Tugade et al., 2004).

Individuals who have coped feel good and assured

they can face future situations successfully. Therefore,

the experience of positive emotions causes the growth

of coping resources, leading to better well-being and

future experiences. The BBT has three perspectives:

the broadening role, the narrowing role, and the

building role (Fredrickson and Joiner, 2002). These

are explored in the following sub-sections.

2.2.1 The Broadening Role

Positive emotions enhance a person’s ability to

recognise and understand external signals (e.g.,

expand their attention scope and improve their ability

to process information). It allows an individual to

expand the range of thoughts and actions they can

take. A broader scope of attention also increases

cognitive variation, which may raise the number of

unique ideas (Amabile et al., 2005). According to

Fredrickson (2004), expanding individuals’

understanding of a particular issue can help them to

solve creative problems. Therefore, an increase in

interaction with an organisation’s information

systems causes employees to seek to protect their

organisations (Posey et al., 2013; Zhen et al., 2020;

Burns et al., 2019). Positive emotions might provide

employees with essential cybersecurity resources as

they increase cognitive agility and broaden

information processing (Fredrickson, 2004; Amabile

et al., 2005). As a result, the BBT argues that positive

emotions enhance security-related thinking and

behaviours.

2.2.2 The Narrowing Role

Fredrickson and Branigan (2005) explain that

negative emotions narrow the focus of thoughts,

although this does not indicate a counter-association

between positive and negative emotions. Positive and

negative emotions independently influence cognition

and behaviour. For example, distrust and trust are

distinct constructs rather than opposing ends of the

same spectrum (e.g., Moody et al., 2014).

Furthermore, negative emotions play a pivotal role in

adaptive behaviour due to their narrowing effects.

They elicit specific actions in response to adaptive

needs (Fredrickson and Branigan, 2005).

2.2.3 The Building Role

Psychological resources such as resilience, optimism

and creativity are gradually developed due to positive

emotions (Fredrickson, 2001). Therefore, a positive

psychology-based paradigm for positive emotions,

hope, well-being, optimism and happiness are all

positive traits linked with positive psychology.

3 HYPOTHESES

DEVELOPMENT

3.1 The Effects of Negative Emotions

on Employees’ Cybersecurity

Protection Motivation Behaviours

Cybersecurity risks are influential precursors of

negative emotions, especially about an individual’s

life goals. For example, employees might develop

negative emotions when they face something

preventing them from achieving their goals (Kemper

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

526

and Lazarus, 1990). Baumeister et al. (2001) stated

that negative emotions affect interpersonal

interactions and predict people’s behaviours.

According to Ayoko et al. (2012), the most

documented negative emotions are anger, fear, and

sadness, which bring out particular behavioural

tendencies in people. These negative emotions affect

employees’ actions and their workplace productivity.

According to Bada and Nurse (2019), cybersecurity

attacks have caused emotional trauma and depression.

Negative emotions that occur as immediate

psychological reactions to cybercrime and have long-

term effects include frustration, distress, insecurity,

fear, sadness, anxiety, disappointment, and anger

(Beaudry and Pinsonneault, 2010; Liang et al., 2019).

Emotional responses can result in different

employee reactions and behaviours (Carmichael and

Piquero, 2004). Beaudry and Pinsonneault (2010)

argue that individuals’ reactions to personal and

professional relevance, especially in IT-based

activities, determine their primary and secondary

appraisals. The primary and secondary assessments

form the negative emotions, anxiety, frustration, and

anger in the information security behaviour of an

employee (Beaudry and Pinsonneault, 2010; Burns et

al., 2019; Gulenko, 2014). The use of technology

causes powerful and negative emotions among people.

For instance, employees’ productivity, well-being,

and learning experience can be influenced by

negative emotions such as frustration, worry, and

anger. Pervez (2010) suggests that emotions

significantly influence employee performance and

that organisations must have employees with a high

level of control over their emotions to increase

productivity. Employees who encounter a

cybersecurity threat are likely to experience negative

emotions, especially when they lack control or self-

efficacy over their emotions or the consequences of

the events. The ability of employees to learn and

memorise is also affected by negative emotions,

leading to poor performance (Izard, 2002). The

negative emotions experienced by employees often

result in poor behaviours such as abuse of work

computers, unqualified password usage, and

ignorance when taking information security

precautions (Burns et al., 2019; Gulenko, 2014). Thus,

it is posited that:

H

1

: Negative emotions promote negative protection

motivation behaviour among employees.

H

2

: Negative emotions promote a negative effect on

employees’ self-efficacy.

3.2 The Effects of Positive Emotions on

Employees’ Cybersecurity

Protection Motivation Behaviours

Positive emotions have been documented to affect

employees' attitudes towards adopting protection

motivation behaviours. Gulenko (2014) posited that

positive emotions could be utilised in preventive

interventions to manage adverse cybersecurity

incidents linked to a lack of cybersecurity awareness.

There have been few studies on the role of positive

emotions in encouraging employees to act in a data

security-conscious manner (Zhen et al., 2020; Burns

et al., 2017; Gulenko, 2014; Burns et al., 2019).

Despite the increasing number of studies examining

how employees adhere to or violate cybersecurity

standards, studies on inside competencies and

emotional elements that allow individuals to

safeguard organisational communication assets

remain limited (Siponen and Vance, 2010;

Farshadkhah et al., 2021). Positive emotions may

encourage employees to defend their information

technology assets against outside and inside threats

(Zhen et al., 2020). Given the substantial impact of

positive emotions on employees’ reactions and

cybersecurity behaviour and awareness, it is

advocated that organisations should motivate

employees by eliciting positive emotions that will

fuel the employee’s protection motivation behaviours.

Therefore, it is posited that:

H

3

: Positive emotions promote positive protective

motivation behaviour among employees.

H

4

: Positive emotions promote a positive effect on

employees’ self-efficacy.

3.3 Self-Efficacy as a Mediating Role in

Protection Motivation Behaviour

Self-efficacy is individual confidence in taking the

necessary actions when facing challenges and

consequently overcoming them successfully

(Bandura, 2004; Compeau & Higgins, 1995).

Research demonstrates that self-efficacy directly

affects the decisions that result in particular (Bandura,

2012). Concerning cybersecurity, self-efficacy is

depicted as an individual's trust in their skills to

protect the information systems’ property from

threats. These are prone to being influenced by

emotions, thus contributing to behaviour that

motivates protection. Negative characteristics such as

low income, upbringing and poor mental health

adversely affect an individual’s self-efficacy (Bingöl,

2018). Self-efficacy can be enhanced by improving

The Influences of Employees’ Emotions on Their Cyber Security Protection Motivation Behaviour: A Theoretical Framework

527

an individual’s physical and emotional states

(Bandura, 2012). Negative emotions such as anxiety

and anger limit a person’s mindset, thus influencing

learning ability and memory retention capabilities

(Gulenko, 2014). According to Mallinckrodt and Wei

(2005), persons who have extreme levels of anxiety

should consider engaging in self-efficacy

enhancement activities. Hence, employees who have

negative emotions experience a self-efficacy deficit.

Positive emotions stimulate cognitive enthusiasm,

which results in proactive thinking that promotes self-

efficacy (Zhen et al., 2020). According to Beaudry

and Pinsonneault (2010), positive emotions

encourage learning and mastery of new skills and

knowledge essential to information systems.

According to the PMT, the risk factors in an

employee’s work environment affect their response to

the individual elements; this response can be either

positive or negative. Employees' response to these

risk factors is usually determined by their awareness

of the threats and their self-efficacy (Ma, 2022). In

this regard, employees must clearly understand the

responsibilities of cybersecurity and the preventive

action that can be taken when faced with the risk

factors that constitute security risks. Self-efficacy is

fundamental if employees adjust and adopt the new

protection motivation behaviours that cultivate self-

efficacy. Thus, it is posited that:

H

5

: Self-efficacy promotes a positive protection

motivation behaviour among employees.

H

6

: Self-efficacy intervenes in negative emotions and

employees’ protection motivation behaviours.

H

7

: Self-efficacy intervenes the positive emotions and

employees’ protection motivation behaviours.

3.4 Employees’ Awareness of

Cybersecurity as the Moderating

Factor

Cybersecurity awareness is defined as the

understanding of policies and practices established to

enhance their knowledge of cyber exposures, risks,

and incidents that emanate from purposeful and

accidental activities (Berkman et al., 2018).

Employees’ awareness in the cybersecurity context

could include general knowledge regarding

cybersecurity practice, the confidence level of their

capacity, and awareness of threats and consequences.

Protecting an organisation’s information systems and

networks can be regarded as the shared responsibility

of every organisation member, pointing to the

importance of cybersecurity awareness in refining

employees’ understanding of how they can protect the

organisation’s data and network systems (Kim, 2017).

Cybersecurity awareness has been linked to helping

moderate emotions and an employee’s level of self-

efficacy (Zhen et al. 2020). Research has indicated

that high levels of cybersecurity awareness can

influence employees’ emotions and self-efficacy

levels efficacy. This study proposes that

cybersecurity awareness weakens the relationship

between negative emotions and self-efficacy and

strengthens the relationship between positive

emotions and self-efficacy. Therefore, it is posited

that:

H

8

: Cybersecurity awareness moderates the direct

relationship between negative emotions and

employees’ protection motivation behaviours.

H

9

: Cybersecurity awareness moderates the

relationship between negative emotions and self-

efficacy.

H

10

: Cybersecurity awareness moderates the direct

relationship between positive emotions and

employees’ protection motivation behaviours.

H

11

: Cybersecurity awareness moderates the

relationship between positive emotions and self-

efficacy.

H

12

: Cybersecurity awareness moderates the

relationship between Self-efficacy and employees’

protection motivation behaviours.

3.5 Effects of Moderated Mediation

Moderated mediation is used as a general expression

to describe various outcomes (Preacher et al., 2007;

Fairchild and McQuillin, 2010). In this study,

‘moderated mediation’ describes all situations during

which the moderating impact is conveyed through

one or more mediating variables. Employees’

negative and positive emotions may impact their

motivation to engage in cybersecurity protection

through the mediating effect of self-efficacy. When

employees have high cybersecurity awareness levels,

negative emotions are less associated with self-

efficacy than self-efficacy is associated with

protection motivation behaviours. However, for

employees with high levels of cybersecurity

knowledge, the relationship between self-efficacy

and positive emotions and between self-efficacy and

protection motivation behaviour will be enhanced.

Cybersecurity awareness might moderate the effect of

self-efficacy as a mediating variable on the

correlation between negative and positive emotions

and employees’ cybersecurity protection motivation

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

528

behaviour. Additionally, an employee with high

levels of cybersecurity awareness may weaken the

relationship between negative emotions and self-

efficacy. Therefore, it is hypothesised that:

H

13

: Cybersecurity awareness moderates the indirect

relationship between negative emotions and

employees’ protection motivation behaviours through

Self-efficacy.

H

14

: Cybersecurity awareness moderates the indirect

relationship between positive emotions and

employees’ protection motivation behaviours through

Self-efficacy.

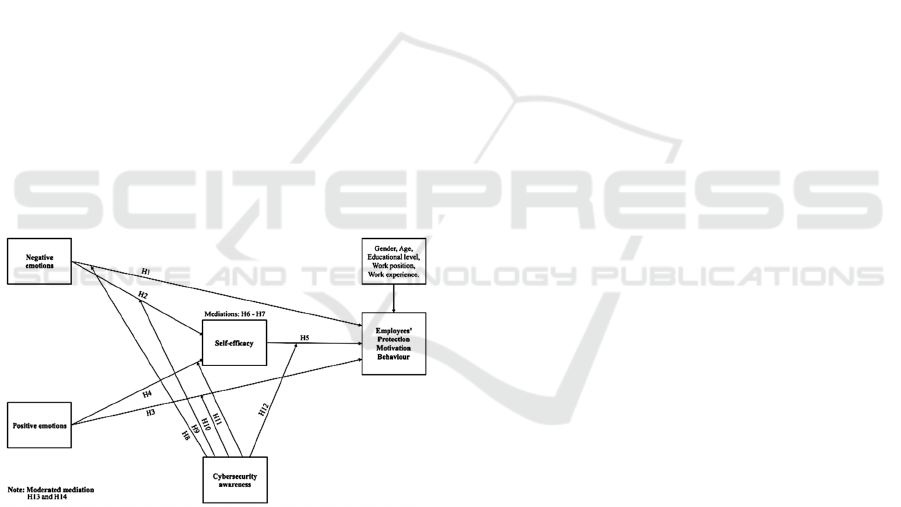

4 THE PROPOSED

FRAMEWORK

Building on the theories mentioned earlier, a

theoretical model is illustrated in Figure 1, which

explains the relationship between employees’

negative emotions, positive emotions, and self-

efficacy as a mediating factor; employees’ awareness

of cybersecurity as a moderator; and employee

protection motivation behaviour. The control

variables included in this model are gender, age,

educational level and organisational work position.

Figure 1: Proposed conceptual framework.

5 CONCLUSION

According to this study, the proposed model may help

measure employee motivation to engage in

cybersecurity protection based on negative and

positive emotions. This model was developed with

two popular theories, PMT and BBT, and the

published literature on emotions in the cybersecurity

context. The conceptual model of research comprises

independent, mediating, and moderating variables.

The independent variables are negative and positive

emotions. The mediating variable is self-efficacy,

while the moderating variable is cybersecurity

awareness. Accordingly, fourteen hypotheses are

formulated to explain the relationships between the

constructs of the research model. The author of this

paper advocates that the PMT and BBT are sufficient

to model employees’ cybersecurity protection

motivation behaviour. The proposed model will be

empirically tested in a future study.

REFERENCES

Amabile, T. M., Barsade, S. G., Mueller, J. S., & Staw, B.

M. (2005). Affect and creativity at work.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 367-403.

Anderson, C., Baskerville, R. L., & Kaul, M. (2017).

Information security control theory: Achieving a

sustainable reconciliation between sharing and

protecting the privacy of information. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 34(4), 1082–1112.

Ayoko, O. B., Konrad, A. M., & Boyle, M. V. (2012).

Online work: Managing conflict and emotions for

performance in virtual teams. European Management

Journal, 30(2), 156–174.

Bada, M., & Nurse, J. R. C. (2019). The Social and

Psychological Impact of Cyber-Attacks. In Emerging

cyber threats and cognitive vulnerabilities. Academic

Press. (pp. 73–92).

Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive

means. Health Education and Behavior, 31(2), 143–

164.

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of

perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of

Management, 38(1), 9–44.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs,

K. D. (2001). Bad Is Stronger Than Good. Review of

General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Beaudry and Pinsonneault. (2010). The Other Side of

Acceptance: Studying the Direct and Indirect Effects of

Emotions on Information Technology Use1. 34(4),

689–710.

Benson, V., & McAlaney, J. (2019). Cybersecurity as a

social phenomenon. Cyber Influence and Cognitive

Threats, January, 1–8.

Beris, O., Beautement, A., & Sasse, M. A. (2015).

Employee rule breakers, excuse makers and security

champions: Mapping the risk perceptions and emotions

that drive security behaviors. ACM International

Conference Proceeding Series, 08-11-Sept, 73–84.

Berkman, H., Jona, J., Lee, G., & Soderstrom, N. (2018).

Cybersecurity awareness and market valuations.

Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 37(6), 508–

526.

Bingöl, T. Y. (2018). Determining the predictors of self-

efficacy and cyber bullying. International Journal of

Higher Education, 7(2), 138–143.

The Influences of Employees’ Emotions on Their Cyber Security Protection Motivation Behaviour: A Theoretical Framework

529

Boss, S. R., Galletta, D. F., Lowry, P. B., Moody, G. D., &

Polak, P. (2015). What do systems users have to fear?

Using fear appeals to engender threats and fear that

motivate protective security behaviors. MIS Quarterly:

Management Information Systems, 39(4), 837–864.

Brands, J., & Van Doorn, J. (2022). The measurement,

intensity and determinants of fear of cybercrime: A

systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior, 127,

107082.

Brooks, A. T., Krumlauf, M., Beck, K. H., Fryer, C. S.,

Yang, L., Ramchandani, V. A., & Wallen, G. R. (2019).

A Mixed Methods Examination of Sleep Throughout

the Alcohol Recovery Process Grounded in the Social

Cognitive Theory: The Role of Self-Efficacy and

Craving. Health Education and Behavior, 46(1), 126–

136.

Bulgurcu, B., Cavusoglu, H., & Benbasat, I. (2010).

Information security policy compliance: An empirical

study of rationality-based beliefs and information

security awareness. MIS Quarterly: Management

Information Systems, 34(SPEC. ISSUE 3), 523–548.

Burns, A. J., Posey, C., Roberts, T. L., & Benjamin Lowry,

P. (2017). Examining the relationship of organizational

insiders’ psychological capital with information

security threat and coping appraisals. Computers in

Human Behavior, 68, 190–209.

Burns, A. J., Roberts, T. L., Posey, C., & Lowry, P. B.

(2019). The adaptive roles of positive and negative

emotions in organizational insiders’ security-based

precaution taking. Information Systems Research, 30(4),

1228–1247.

Carmichael, S., & Piquero, A. R. (2004). Sanctions,

Perceived Anger, and Criminal Offending. Journal of

Quantitative Criminology, 20(4), 371–393.

Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Computer self-

efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test.

MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems,

19(2), 189–210.

Cram, W. A., Proudfoot, J. G., & D’arcy, J. (2017).

Organizational information security policies: a review

and research framework. European Journal of

Information Systems, 26, 605–641.

D’Arcy, J., Herath, T., & Shoss, M. K. (2014).

Understanding Employee Responses to Stressful

Information Security Requirements: A Coping

Perspective. Journal of Management Information

Systems, 31(2), 285–318.

DataReportal. (2023). DIGITAL AROUND THE WORLD.

https://datareportal.com/global-digital-overview

Fairchild, A. J., & McQuillin, S. D. (2010). Evaluating

mediation and moderation effects in school psychology:

A presentation of methods and review of current

practice. Journal of School Psychology,

48(1), 53–84.

Farshadkhah, S., Van Slyke, C., & Fuller, B. (2021).

Onlooker effect and affective responses in information

security violation mitigation. Computers and Security,

100, 102082.

Fredrickson, B. (2001). The Role of Positive Emotions in

Positive Psychology. The American Psychologist, 56,

218–226.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of

positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the

Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449),

1367–1377.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive

emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-

action repertoires. Cognition and Emotion, 19(3), 313–

332.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions

trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being.

Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175.

Gulenko, I. (2014). Improving passwords: influence of

emotions on security behaviour. Information

Management & Computer Security, 22(2), 167–178.

Herath, T., & Rao, H. R. (2009). Protection motivation and

deterrence: A framework for security policy

compliance in organisations. European Journal of

Information Systems, 18(2), 106–125.

I. M. Y. Woon., Tan., W., & R. T. Low. (2005). A

PROTECTION MOTIVATION THEORY APPROACH

TO HOME WIRELESS SECURITY. 5, 186–204.

Ifinedo, P. (2012). Understanding Information systems

security policy compliance. Computers and Security,

31(1), 83–95.

Izard, C. E. (2002). Translating emotion theory and

research into preventive interventions. Psychological

Bulletin, 128(5), 796–824.

Jansen, J., & van Schaik, P. (2018). Persuading end users to

act cautiously online: a fear appeals study on phishing.

Information and Computer Security, 26(3), 264–276.

Kemper, T. D., & Lazarus, R. S. (1990). Emotion and

Adaptation. Contemporary Sociology, 21(4), 522.

Khan, H. U., & AlShare, K. A. (2019). Violators versus

non-violators of information security measures in

organizations—A study of distinguishing factors.

Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic

Commerce, 29(1), 4–23.

Kim, L. (2017). Cybersecurity awareness: Protecting data

and patients. Nursing Management, 48(4), 16–19.

LaRose, R., Rifon, N. J., & Enbody, R. (2008). Promoting

personal responsibility for internet safety.

Communications of the ACM, 51(3), 71–76.

Liang, H., Xue, Y., Pinsonneault, A., & Wu, Y. (2019).

What users do besides problem-focused coping when

facing it security threats: An emotion-focused coping

perspective. MIS Quarterly: Management Information

Systems, 43(2), 373–394.

Lowry, P. B., & Moody, G. D. (2015). Proposing the

control-reactance compliance model (CRCM) to

explain opposing motivations to comply with

organisational information security policies.

Information Systems Journal, 25(5), 433–463.

Ma, X. (2022). IS professionals’ information security

behaviors in Chinese IT organizations for information

security protection. Information Processing and

Management, 59(1), 102744.

Mallinckrodt, B., & Wei, M. (2005). Attachment, social

competencies, social support, and psychological

distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3),

358–367.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

530

McCormac, A., Calic, D., Parsons, K., Butavicius, M.,

Pattinson, M., & Lillie, M. (2018). The effect of

resilience and job stress on information security

awareness. Information and Computer Security, 26(3),

277–289.

Moody, G. D., Galletta, D. F., & Lowry, P. B. (2014). When

trust and distrust collide online: The engenderment and

role of consumer ambivalence in online consumer

behavior. Electronic Commerce Research and

Applications, 13(4), 266–282.

Pervez, M. A. (2010). Impact of emotions on employee’s

job performance: An evidence from organizations of

Pakistan. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable

Development, 1(5), 11–16.

Posey, C., Roberts, T. L., Lowry, P. B., Bennett, R. J., &

Courtney, J. F. (2013). Insiders’ protection of

organizational information assets: Development of a

systematics-based taxonomy and theory of diversity for

protection-motivated behaviors. MIS Quarterly:

Management Information Systems, 37(4), 1189–1210.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007).

Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory,

methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral

Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A Protection Motivation Theory of

Fear Appeals and Attitude Change1. The Journal of

Psychology, 91(1), 93–114.

Rogers W., R. (1983). Cognitive and physiological

processes in fear appeals and attitude change: a revised

theory of protection motivation. In Social

Psychophysiology: A Sourcebook (pp. 153–177).

Siponen, M., & Vance, A. (2010). Neutralization: New

Insights into the Problem of Employee Information

Systems Security Policy Violations1. MIS Quarterly,

34(3), 487–502.

Snyman, D. P., Kruger, H., & Kearney, W. D. (2018). I

shall, we shall, and all others will: paradoxical

information security behaviour. Information and

Computer Security, 26(3), 290–305.

Spanaki, K., Gürgüç, Z., Mulligan, C., & Lupu, E. (2019).

Organizational cloud security and control: a proactive

approach. Information Technology and People, 32(3),

516–537.

Spidalieri, F., & Kern, S. (2014). Professionalizing

Cybersecurity: A path to universal standards and status.

401.

Tugade, M. M., Fredrickson, B. L., & Barrett, L. F. (2004).

Psychological resilience and positive emotional

granularity: Examining the benefits of positive

emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality,

72

(6), 1161–1190.

Zamani, E. D., & Pouloudi, N. (2021). Generative

mechanisms of workarounds, discontinuance and

reframing: a study of negative disconfirmation with

consumerised IT. Information Systems Journal, 31(3),

384–428.

Zhen, J., Xie, Z., & Dong, K. (2020). Positive emotions and

employees’ protection-motivated behaviours: A

moderated mediation model. Journal of Business

Economics and Management, 21(5), 1466–1485.

The Influences of Employees’ Emotions on Their Cyber Security Protection Motivation Behaviour: A Theoretical Framework

531