Building Suitable Observation Points to Enhance the Learner’s

Perception of Information in Virtual Environment for Gesture Learning

Vincent Agueda

1,2

, Ludovic Hamon

1

, S

´

ebastien George

1

and Pierre-Jean Petitprez

2

1

LIUM, EA 4023, Le Mans Universit

´

e, 72085 Le Mans, Cedex 9, France

2

HRV Simulation, 53810 Chang

´

e, France

Keywords:

Technical Gesture, Virtual Learning Environment, Motion Capture, Pedagogical Resources.

Abstract:

This paper presents an architecture to build Virtual Pedagogical Resources (VPR) dedicated to gesture learn-

ing. This architecture proposes: (a) to replay any captured gesture from an expert, in a 1:1-scaled Virtual

Environment (VE) using a Virtual Reality (VR) headset (b), a full control of the replay process (play, pause,

speed control, replay, etc.) and (c), a method to generate observation points from the activity traces of the

learners in their observation process. Most of the Virtual Learning Environments (VLE) dedicated to gesture

learning, put the learner into a practising process, neglecting the observation and study time of the gesture to

learn. In addition, the VLE with dedicated observation functionalities are very specific to the task to learn,

or lack of relevant strategies regarding the appropriate viewpoints to recommend. Therefore, this work in

progress proposes a method able to make a VLE as a relevant pedagogical resource for observing and study-

ing the gesture outside or during the practical session, with the appropriate point of view. A description of a

first experiment is presented, which aims at validating the consistency and the pedagogical relevance of the

generated viewpoints.

1 INTRODUCTION

Teaching technical skills has always been a specific

case of education because of the involved tacit knowl-

edge. This includes gesture learning i.e. motor skills

linked to the underlying motions, performed for a par-

ticular purpose in a specific context. There are three

main non-exclusive teaching methods: (i) gesture vi-

sualization followed by practising (ii), learning spe-

cific constraints/features defined by geometric, kine-

matic or dynamic properties of the movement and

(iii), considering the gesture as a sequence of actions

focusing more on the goal to reach than the motion

to perform. Outside of being tutored by an expert,

different pedagogical resources exist as alternatives

when the latter is absent, such as books with pictures

describing motions with schemes, and videos demon-

strating them. Both of those resources come with their

advantages and disadvantages.

There are software tools for the biomechanical

analysis of motions, mainly dedicated to the sport and

health domains such as Motion Analysis, Kinovea,

Qualisys, etc. They provide, in particular, a motion

visualisation, statistical functionalities, graph display-

ing based on geometric and kinematic criteria. How-

ever, these tools were not designed as Virtual Learn-

ing Environments (VLE), making them difficult to use

as simulators for training, especially if one does not

have a biomechanics expertise. Nevertheless, with

the emergence of motion capture technologies, novel

learning tools have been designed offering a new kind

of teaching. In this context, Virtual Reality (VR) has

increasingly become the focus of attention, thanks to

its ability to immerse users in a rich and compelling

Virtual Environment (VE). Indeed, learners can focus

on their task while VE provides real-time pedagog-

ical feedback (Oagaz et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2020;

Wu et al., 2020). Furthermore, motion capture allows

saving and reusing captured gestures executed by an

expert to automatically evaluate learners by compar-

ison, or replay them in VE. This allows the learning

situation to dynamically evolve with or without the

expert. In case of a replay, the gesture is reproduced

through a 3D virtual anthropomorphic avatar that rep-

resents a human in VE (Chen et al., 2019; Zhao, 2022;

Esmaeili et al., 2017).

Works and studies on VLE using 1:1-scale VE

with a VR headset, and dedicated to gesture learning

have already been done in various fields of work (Liu

et al., 2020; Rho et al., 2020; Jeanne et al., 2017).

428

Agueda, V., Hamon, L., George, S. and Petitprez, P.

Building Suitable Observation Points to Enhance the Learner’s Perception of Information in Virtual Environment for Gesture Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0012686100003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 428-435

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

The main contributions of those studies are linked to

the design and the impact on the learning situation.

One can also observe that most of previous works

focus on immediate practising, neglecting the neces-

sary discovering and observation time. In most cases,

only basic functionalities are available to the learner,

limiting them to get in depth the necessary informa-

tion of a gesture from the temporal and spatial view-

point (Oagaz et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2019). Even

with the possibility to observe the 3D avatar from any

angle using a VR headset, the learner may struggle

to effectively discover and integrate the related skills

and knowledge if the appropriate viewpoints are not

found. It is crucial to provide a clear guidance on

where, when and what to observe in this context, and

consequently, propose the appropriate viewpoints in

order to maximize the perceived information related

to the gesture to learn. This work raises the ques-

tion of designing an interactive and appropriate VLE

for maximizing the perception of a 3D avatar to effec-

tively learn a gesture, according to the needs and prac-

tices of the users (learners and teachers). However,

the literature misses of works detailing a complete

production chain to build adapted Virtual Pedagogi-

cal Resources (VPR) for gesture learning. A VPR is

defined as a virtual resource made of VE in which

a technical captured gesture can be observed in time

and space for gesture learning, the VPR being used

in the learning process during practical sessions and

beyond, as long as the user has the necessary equip-

ment. In this work in progress, a system architecture

for creating VPR designed for gesture learning will be

described, and an experimental protocol is formalized

to validate the architecture. Section 2 presents the

contributions made by the article. Section 3 reviews

VLE for gesture learning that includes a 3D human-

based avatar. Section 4 presents the proposed system

architecture for replaying any captured movement in

VLE, and including an automatic observation point

recommendation system. Section 5 proposes a proto-

col allowing to evaluate the coherence of the gener-

ated observation points, while providing initial feed-

back from the learners on VPR. Section 6 discusses

the protocol, the design choices, and the article con-

cludes with Section 7.

2 CONTRIBUTIONS

This article does not study VLE as a practice tool

but as a visualization tool. In this way, studying the

learner’s performances and skills after using either the

VLE or any other kinds of resources is out of the

scope of this work in progress in terms of contribu-

tions. This article focuses on identifying the features

where the information is best perceived and what the

challenges and methods are to design effective VPR

adapted to the gesture to learn.

This paper proposes a complete process and its un-

derlying system architecture able to replay any cap-

tured movement in a VLE and recommend relevant

observation points to learners, thereby enhancing the

perceived information and their learning experience.

This system allows the learner to visualize the ges-

ture at any time outside of teaching hours. A first ap-

plication case is also presented with a load lift and

displacement to prevent gestures leading to Muscu-

loSkeletal Disorders (MSD).

3 RELATED WORKS

Most existing VLE for gesture learning are just con-

sidered as a tool for practical sessions and not as a

fully new learning resource. The use of a 3D avatar

combined with motion capture for gesture learning

purposes has already been studied in a context of skill

acquisition for the specific tasks they were designed

for. As a result, they are mainly used for practising. If

available, the VLE can offer basic media player func-

tionalities and a free navigation, without providing

any observation guidance. This section reviews exist-

ing VLE for gesture learning that include a 3D avatar.

For each work, four main topics are covered: (a) the

gesture or task to learn (b), the VLE functionalities

based on the interactions available to the learner (c),

the presence of observation points, their features, and

design process, and (d), the potential use of the VLE

as a pedagogical resource.

The combination of VLE and motion capture for

enhancing gesture learning has already been studied

in many domains such as sport (Liu et al., 2020; Wu

et al., 2020; Oagaz et al., 2022; Zhao, 2022; Chen

et al., 2019), sign language (Rho et al., 2020) and in-

dustry (Jeanne et al., 2017). The use of motion cap-

ture depends on the used strategy of the captured data:

the motion can be used for evaluation purposes, ob-

servation by replay, or in a combination of the two

previous points. However, the main objective is the

same: to evaluate the acquisition of motor skills by

using those VLE.

When motion capture is added, the first strategy is

to assess the gesture done by the learner in real time

(or close) during the practical session. The expert’s

gesture is captured beforehand and then used to eval-

uate the learner by comparison. Zhao (2022) applied

this method in a VLE dedicated to Yao dance teach-

ing where students, while wearing a motion capture

Building Suitable Observation Points to Enhance the Learner’s Perception of Information in Virtual Environment for Gesture Learning

429

equipment, practiced the dance. The system gave in-

stant feedback to them. It is important to note that

only the student’s gesture was displayed on the screen

and not the expert’s one. In addition, the pedagogi-

cal feedback was displayed through highlighted body

parts depending on the executed gesture. It was not

the case for Oagaz et al.’s work for table tennis, where

the student and expert gestures were simultaneously

shown while the evaluation was running (Oagaz et al.,

2022). The learners can observe and imitate the ges-

ture performed by the expert’s 3D avatar, while the

learner’s gesture was evaluated by comparing the tilt-

ing of different body joints (elbow, wrist, knees, etc.)

displayed on the second 3D avatar.

A captured gesture replayed in a VLE may origi-

nate from a teacher or an expert (Esmaeili et al., 2017;

Nawahdah and Inoue, 2013), a learner (Zhao, 2022)

or both (Liu et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2019; Oagaz

et al., 2022). Depending on which one is replayed

between the expert or the learner, the VLE design ob-

jectives and main functionalities may vary. Replaying

the teacher’s motions often aims at following the imi-

tation learning method. In this case, the 3D avatar can

be: (a) placed in front of them or (b) observed from

any viewpoint by navigating in the VLE or moving

the expert’s 3D avatar (Esmaeili et al., 2017; Nawah-

dah and Inoue, 2013; Wu et al., 2020). Replaying

the student’s gesture is also often linked to an auto-

matic evaluation process, with the feedback displayed

on the student’s 3D avatar (Zhao, 2022). Finally,

the combination of both displays allows combining

observation and evaluation (Liu et al., 2020; Oagaz

et al., 2022). Replaying a captured motion in a VLE

can also mean that player-type controls (play, pause,

decreasing speed, etc.) are available to the learner.

However, not all works precisely describe whether

those kinds of interactions are available or not (Es-

maeili et al., 2017). Nevertheless, in works indicating

the available functionalities, one can note the play and

pause options (Oagaz et al., 2022; Rho et al., 2020), or

replaying the gesture from the beginning (Chen et al.,

2019; Rho et al., 2020). Finally, other more advanced

options such as fast-forward, rewind, or speed control

are rarer (Liu et al., 2020).

With the possibility of displaying a 3D avatar

demonstrating the gesture, the question ”how the

avatar should be observed” emerge, and that question

is answered at different levels. The first one is by giv-

ing one static and fixed viewpoint to the learner (Chen

et al., 2019). A second method allows users to freely

move in VLE or around the expert’s 3D avatar to ob-

serve the replayed gesture from any view angle. This

allows the student to visualize and acquire more in-

formation from the 3D avatar compared to a single

fixed point (Liu et al., 2020). However, students may

not know the most appropriate viewpoint if existing.

Therefore, in order to guide the learner more effec-

tively, the VLE can provide specific and predefined

viewpoints for a better observation and understanding

of the gesture. Esmaeili et al. (2017) implemented

floor squares at locations defined by the expert, where

the learner can observe more effectively some specific

parts of the gesture.

Defining appropriate viewpoints can be tedious.

Given the complexity of the gesture, a large num-

ber of viewpoints must be defined. In addition, the

number and location of these points may differ de-

pending on the gesture. Some gestures may require

more points than others, with different positions and

orientations, particularly in a VLE using a VR head-

set. Moreover, the definition of an appropriate ob-

servation point can differ between experts. An ex-

pert can use the VLE to place the points themselves

in an empirical way. Consequently, this raises the

question of the automatic generation of viewpoints,

especially if one wants to expand the scope of VLE to

include other gestures. Mamoun Nawahdaha and In-

oue (2013) proposed a system where the learner was

static. The position and orientation of the expert’s 3D

avatar around the learner changed, based on the ges-

ture made at each moment, for example, depending

on the arm used for the task. Based on a survey and

experiments coupled to the expert’s captured gesture,

their work allowed achieving an ideal placement of

the 3D avatar, according to the expert’s used hand dur-

ing the demonstration and its position to enhance the

learning. However, to our knowledge, no past works

cover the automatic generation of observation points

in a VLE around the expert’s 3D avatar.

In the context of this study, there are three over-

looked aspects. The first one is related to the ac-

quisition of information when observing a 3D avatar.

Few articles address the optimal configurations to bet-

ter perceive the information when observing a ges-

ture. Next, the analysis of all the works highlights

the absence of a detailed and complete description of

the architecture of the whole system, from the cap-

ture of the expert movement to the building of an

appropriate and interactive VPR. Finally, the com-

parison between appropriate observation-based VLE

and other resources (book and video, for example) in

terms of perception of information linked to gesture-

based skills has not been enough studied.

Based on current state-of-the-art, the presented

work relies on the following research question:

• How to design Virtual Pedagogical Resources

dedicated to gesture learning from captured move-

ments, that maximize the learner’s perception of

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

430

the gesture to learn?

The following section presents the proposed sys-

tem architecture for building an interactive VPR from

a captured movement, including the method to auto-

matically generate the observation points.

4 SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE

In the proposed process, the gesture of the teachers

are captured with any motion capture equipment, as

long as the Capture Module outputs the animation as

a FBX or BVH file. It is important to note that the

captured movement has already been processed (noise

filtering, gap filling, etc.) before being imported in the

system, which is outside the scope of this paper.

4.1 Virtual Learning Environment

Afterwards, the teacher can import the animation file

to the VLE, where the learner will be able to visual-

ize it. The proposed system is currently implemented

with the Unreal Engine, and aims at building a VPR

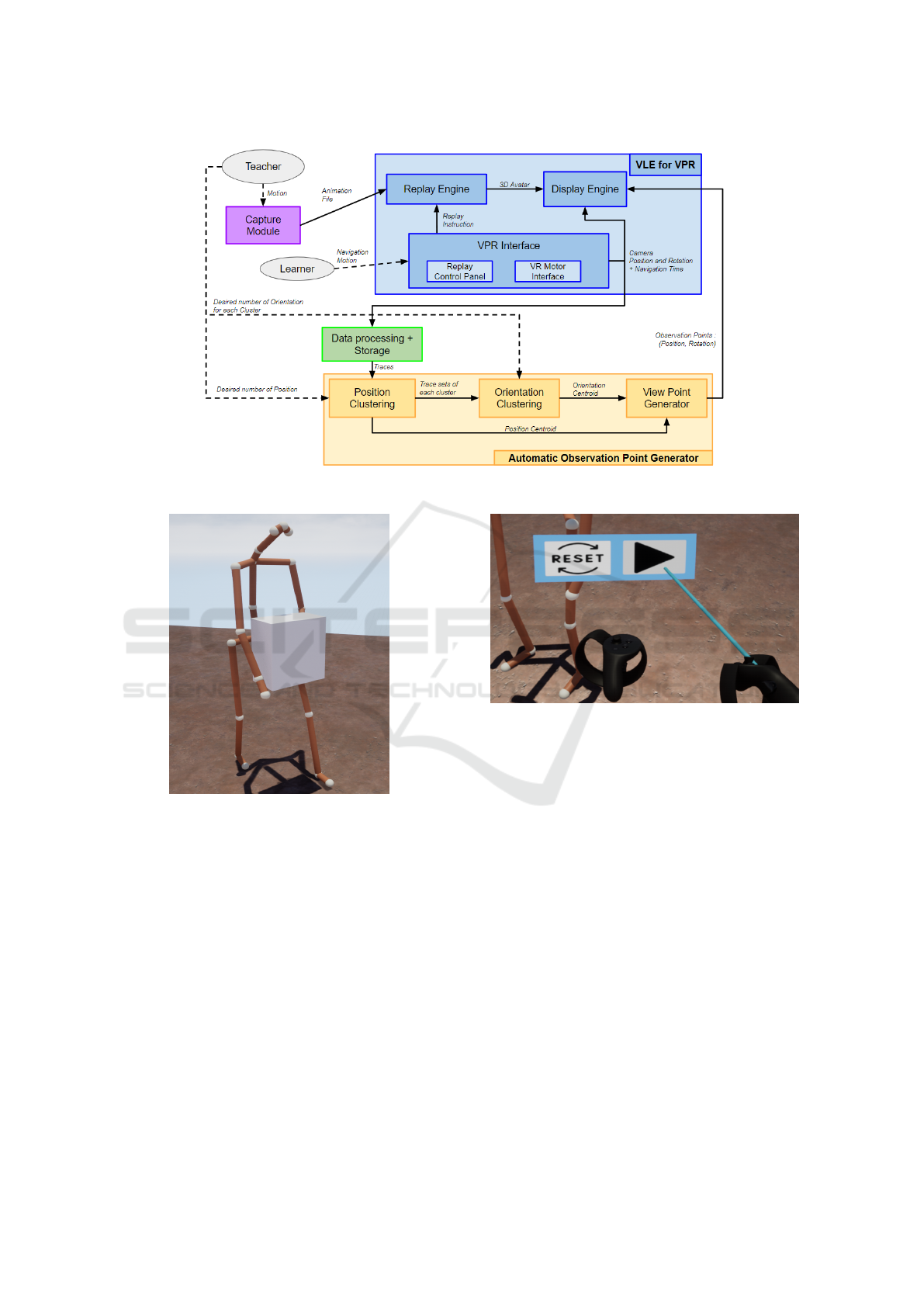

thanks to three main modules (fig. 1):

• The Replay Engine: the data of the animation file

are extracted and stored in a new data structure

to manage different file types for different mo-

tion capture systems. The state and temporal vari-

ables related to the replay are instanced to manage

its features (play, pause, restarting the animation,

and, in the future, speed control and move for-

ward/backward). Whenever a replay is going on,

the Replay Engine module will know which time

of the animation should be played based on its

variables and the learner’s interactions, and will

return the corresponding posture data of the 3D

avatar to the display module.

• The Display Engine renders the 3D avatar in the

VLE, in which the learner is able to navigate and

observe without any restriction (fig. 2). The de-

sign of the VLE must be simple, for example a

platform with no specific objects. If the gesture

implies the manipulation of 3D objects, those ob-

jects must be captured and a 3D mesh must be

defined and manually associated.

• The VPR Interface module allows the learner to

interact and observe the 3D avatar reproducing the

gesture in a 1:1-scaled VE through a VR Headset.

The learner can freely walk in the environment to

observe the 3D avatar from any point of view. A

Replay Control Panel is also available to interact

with the 3D avatar with the replay functionalities

available thanks to the replay engine (fig. 3). Fi-

nally, the interface sends the learner’s headset po-

sition and rotation to the Display Engine to spawn

and position the learner in the Environment.

4.2 Automatic Observation Point

Generator

The user’s navigation traces (position and rotation)

are recorded and exported in a file. With these data,

it is possible to track the learner’s position and orien-

tation of their head throughout the simulation. Those

traces are saved on the basis of a first assumption for

this work: the most used, consistent and efficient ob-

servation points can be computed from the free ob-

servation practical activity. This problem can be for-

malized with the following question: do several con-

sistent sets of close data, made of headset positions

and orientations exist in the traces, obtained from an

activity where the user freely navigates in the VLE to

observe the gesture? This is an unsupervised problem

where a clustering approach must be applied.

Clustering allows to group data based on specific

similarities. In this case, the data are the user’s posi-

tions and orientations of the headset. This method can

be paired with the eye-tracking technology, for exam-

ple by allowing to know what the specific parts of the

screen the user is looking at are. Works have already

been done combining VR, Eye Tracking and cluster-

ing for attention tasks (Bozkir et al., 2021). How-

ever, data defining the position and orientation of the

headset seems to be poorly used. Different cluster-

ing algorithms exist, each being optimized for differ-

ent contexts, and for this work the DBSCAN methods

will be used (Kraus et al., 2020). The DBSCAN al-

gorithm is a density-based clustering method that can

create an unspecified number of clusters based on two

parameters: ε is the radius around a point defining its

neighbourhood, and MinPts the minimum of points

inside that radius in order to shape a dense region.

This choice is based in particular on two features: it

is not limited to spherical clusters and can exclude

outliers in contrary of K-means, for example. In ad-

dition, one can choose the distance function (default:

Euclidean) and make their own distance function if

necessary when dealing with specific data such as an-

gles, for example, or heterogeneous ones.

The Automatic Observation Point Generator

(AOPG) system will get the data from the traces and

apply two DBSCAN:

• The first clustering is done on the positions. This

allows outputting a number K of clusters. This

number is specified by the teacher beforehand,

Building Suitable Observation Points to Enhance the Learner’s Perception of Information in Virtual Environment for Gesture Learning

431

Figure 1: Architecture of the Virtual Pedagogical Resource and the generator.

Figure 2: A 3D Avatar replaying the captured gesture, here,

lifting a load.

and inputted in the clustering process by adjust-

ing the aforementioned two parameters to reach

K. For each cluster, the resulting centroid will

be the generated observation point location. This

specific position and the data set of its belonging

cluster are sent to the next clustering.

• From each K position cluster, a second cluster-

ing is performed on the orientation part of each

trace belonging to the cluster. The teacher also

specifies the desired number L of orientations for

each observation point location, the clustering in-

puts being adjusted in the same way to reach L.

The resulting centroids are the generated orienta-

tions associated with the current observation point

location.

Figure 3: One panel of the Replay Control Panel limited to

the play/pause and reset functionalities for the experiment.

After passing through the two clustering phases,

the system will compute K × L observation points.

Finally, the AOPG system sends those observation

points to the Display Engine module so that each one

can be proposed to the learner.

5 SYSTEM EXPERIMENT

The system needs to be tested and validated from

computing and information perception considera-

tions. The objective of this first experiment is dual:

(a) comparing the information perception between

a VPR and other resources (books or videos) in a

gesture-based learning context and (b), evaluating the

generated observation points in terms of consistency

of the obtained centroids, acting as relevant view-

points from the perspective of the information percep-

tion. The experiment will also provide initial feed-

back from learners on the proposed VPR.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

432

5.1 Protocol

The main lines of the experimental protocol are the

following: each learner must learn a technical ges-

ture by either observing it in the VLE (Test group) or

through a pedagogical video (Control group). After-

wards, the learner will reproduce the observed gesture

in the real world while being evaluated on simple cri-

teria. Each participant is randomly assigned to one of

the two groups.

No additional information is provided to the

learner regarding the expected features of the ges-

ture to learn. Indeed, the learner must reproduce the

gesture based only on the visual information taken

from the motion displayed through the VPR or the

video. The video was taken from internet and mod-

ified to avoid any textual or audio information. Af-

ter being modified, the video is made of six view-

points

1

. The expert reproduces the gesture seen in

the video as closely as possible, and is recorded with

the Qualisys

®

motion capture system. The VLE and

the video will have the same control functionalities

in terms of gesture replaying. Participants in the test

group can freely navigate in the VLE using the VR

headset. The gesture to learn consists in lifting, dis-

placing and depositing a box.

Figure 4: An example of a lifting tutorial.

A list of criteria is drawn up according to the orig-

inal pedagogical video to evaluate the gesture repro-

duced by the learner. A subset of the selected crite-

ria is chosen to easily observe them when the learner

performs the gesture in the real world. As an exam-

ple, a subset of some criteria can be a straight back,

the position of the feet during the lift and deposit, the

placement of the hands to hold the box, etc.

After completing a first questionnaire regarding

different aspects like their previous experience with

VR, the learner will be briefed on the protocol they

will follow and the available interactions. The learner

begins to observe the gesture to learn, either from the

video or in the VLE. They can spend any amount of

1

Click here to access the video of the gesture.

time for the observation. The traces are saved for the

generation of observation points, while the video’s

screen is recorded for further analysis. Once the

learners decide to stop their first observation, they are

invited to reproduce the gesture with a real box once,

while they are rated based on the predefined set of cri-

teria. If at least one of the criteria is not respected, the

learner is informed but not told which one. Indeed,

the learner has to find the expected criteria to evaluate

the quality of the perceived information. After this

first try, they are invited to watch again their resource

in order to repeat the sequence (watching/performing)

five times. Finally, the learner is invited to complete

a second questionnaire made of three parts: an open-

ended question on what the evaluation criteria are ac-

cording to them, a self-assessment on their perfor-

mances based on the real criteria, and lastly their feed-

back on the resource used.

At the end of the experiment, the VLE will pro-

duce the traces, consisting of the learner’s positions

and orientations. The video traces will be analysed to

get the observation time for each pass, and the used

interactions during the observation (Play/Pause and

Reset usage). The VLE traces will be used in the

AOPG system to generate observation points for anal-

ysis.

5.2 Result Analysis

The consistency and the pedagogical relevance of

the generated observation points must be evaluated.

Three different methods can be used:

• Clustering Consistency: a first verification con-

sists in using the Average Silhouette Score (ASS)

metric. It is based on the average of the Silhouette

Score (SS) of each data point, which is a mea-

sure giving how close each point of a cluster is

from points of other clusters. This metric outputs

an indication of the homogeneity and separabil-

ity (including the non-overlapping aspect) of each

cluster from the others (Hussein et al., 2021).

• Pedagogical Relevance: an expert validation will

also be used as a verification method by approving

the generated observation points. The method will

be based on the Inter-rater reliability, where two

or more judges independently evaluate the gener-

ated observation points. The degree of agreement

between them is estimated thanks to the Cohen’s

Kappa coefficient (Eagan et al., 2020).

• Impact on Gesture Learning: a third verifica-

tion can also be done through a second experi-

mentation where the generated observation points

are compared with the expert’s observation points

Building Suitable Observation Points to Enhance the Learner’s Perception of Information in Virtual Environment for Gesture Learning

433

in terms of learner skill acquisition. This experi-

mentation will focus more on the learner’s perfor-

mances according to the observation points used

in order to compare them.

Finally, one can note that the proposed protocol

does not aim at evaluating the task performances be-

tween the two groups, this kind of experiment (i.e.

VLE vs. traditional teaching methods) being done

multiple times in the literature (Cannav

`

o et al., 2018;

Zhao, 2022). However, this could be the topic of a

second experiment once the observation points max-

imizing the perception of the most important gesture

features are found and integrated in the VPR.

6 DISCUSSION

The results of the experiment must ensure that the

main goals are met, i.e. the generated observation

points are consistent and relevant, and the user satis-

faction with the VPR is at least acceptable (through

the S.U.S questionnaire for example (Corr

ˆ

ea et al.,

2017)). If these objectives are reached, the sys-

tem can therefore be considered as hopeful for cre-

ating VPR for gesture learning and teaching, in-

cluding recommendations regarding the observation

points. Afterwards, the generated observation points

will be studied from the perspective of information

perception in comparison to other methods defining

them (Teacher’s proposal, teacher’s trace analysis, de-

ducted from known and admitted books or videos

in the considered application domain, etc.). How-

ever, the generator tool only takes in consideration the

learner’s traces for generating the observation points.

The teacher’s expertise is not formally integrated in

the system in order to improve the generator. One

possible solution is to analyse the teacher’s traces

when using the environment to generate the observa-

tion points. However, the teachers, by their exper-

tise, will not navigate to discover the gesture. Their

proposal could be limited to predefined observation

points recommended by their empirical experience,

avoiding the discovering of new ones. Nonetheless,

their expertise must be considered. The proposed pro-

tocol also presents another way to integrate the teach-

ers: by letting them validate the generated observa-

tion points, computed from learner traces, before be-

ing sent to the VLE.

Furthermore, the current system misses different

aspects. The first one is related to the animation time.

A learner can decide at any moment to pause the ani-

mation to look in detail a specific posture while turn-

ing around it. This can lead to observation points that

are only consistent for a specific animation time and

not for the overall gesture. Consequently, the follow-

ing works must extend the architecture to consider the

animation time, alongside other parameters like the

user inputs with the replay control panel for the gen-

eration of observation points.

The other aspect is related to the user’s eye gaze.

As for now, the system defines the observation as the

head’s position and orientation in the 3D space. This

must be completed with the eye gaze, as eyes can fo-

cus on different objects in the field of view of the cur-

rent defined observation point. is Using eye-tracking

technologies is one way to extract the eye gaze, such

as the one implemented in the Oculus Quest Pro head-

set. However, the first version of the architecture must

be validated as the eye gaze must be analysed only

with validated observation viewpoints.

7 CONCLUSION &

PERSPECTIVES

This article presents an architecture that allows build-

ing a VPR dedicated to the interactive observation of

a gesture to learn. Using a captured gesture of an ex-

pert and a VR Headset, any learner can then observe

the 3D avatar replays the gesture from any point of

view, and control the replay (play, pause, speed con-

trol, replay, etc.). The learners’ traces including their

head positions and orientations are sent to the cluster-

ing process for generating observation point recom-

mendations. These viewpoints can help the learner in

perceiving the relevant features of the gesture to learn.

In the future, the system will be tested in an experi-

ment to evaluate the consistency and the pedagogical

relevance of the generated viewpoints, as well as the

ability of the built VPR to convey the appropriate fea-

tures of the gesture to learners.

REFERENCES

Bozkir, E., Stark, P., Gao, H., Hasenbein, L., Hahn, J.-

U., Kasneci, E., and G

¨

ollner, R. (2021). Exploiting

Object-of-Interest Information to Understand Atten-

tion in VR Classrooms. In 2021 IEEE Virtual Reality

and 3D User Interfaces (VR), pages 597–605. ISSN:

2642-5254.

Cannav

`

o, A., Prattic

`

o, F. G., Ministeri, G., and Lamberti,

F. (2018). A Movement Analysis System based on

Immersive Virtual Reality and Wearable Technology

for Sport Training. In Proceedings of the 4th Inter-

national Conference on Virtual Reality, ICVR 2018,

pages 26–31, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Chen, X., Chen, Z., Li, Y., He, T., Hou, J., Liu, S., and He,

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

434

Y. (2019). ImmerTai: Immersive Motion Learning in

VR Environments. Journal of Visual Communication

and Image Representation, 58:416–427.

Corr

ˆ

ea, A. G., Borba, E. Z., Lopes, R., Zuffo, M. K.,

Araujo, A., and Kopper, R. (2017). User experience

evaluation with archaeometry interactive tools in Vir-

tual Reality environment. In 2017 IEEE Symposium

on 3D User Interfaces (3DUI), pages 217–218.

Eagan, B., Brohinsky, J., Wang, J., and Shaffer, D. W.

(2020). Testing the reliability of inter-rater reliability.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference

on Learning Analytics & Knowledge, LAK ’20, pages

454–461, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

Esmaeili, H., Thwaites, H., and Woods, P. C. (2017).

Immersive virtual environments for tacit knowledge

transfer focusing on gestures: A workflow. In 2017

23rd International Conference on Virtual System &

Multimedia (VSMM), pages 1–6. ISSN: 2474-1485.

Hussein, A., Ahmad, F. K., and Kamaruddin, S. (2021).

Cluster Analysis on Covid-19 Outbreak Sentiments

from Twitter Data using K-means Algorithm. Jour-

nal of System and Management Sciences.

Jeanne, F., Thouvenin, I., and Lenglet, A. (2017). A study

on improving performance in gesture training through

visual guidance based on learners’ errors. In Proceed-

ings of the 23rd ACM Symposium on Virtual Real-

ity Software and Technology, VRST ’17, pages 1–10,

New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Ma-

chinery.

Kraus, M., Weiler, N., Oelke, D., Kehrer, J., Keim, D. A.,

and Fuchs, J. (2020). The Impact of Immersion on

Cluster Identification Tasks. IEEE Transactions on Vi-

sualization and Computer Graphics, 26(1):525–535.

Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Visualiza-

tion and Computer Graphics.

Liu, J., Zheng, Y., Wang, K., Bian, Y., Gai, W., and Gao,

D. (2020). A Real-time Interactive Tai Chi Learning

System Based on VR and Motion Capture Technol-

ogy. Procedia Computer Science, 174:712–719.

Nawahdah, M. and Inoue, T. (2013). Setting the best view of

a virtual teacher in a mixed reality physical-task learn-

ing support system. Journal of Systems and Software,

86(7):1738–1750.

Oagaz, H., Schoun, B., and Choi, M.-H. (2022). Real-time

posture feedback for effective motor learning in ta-

ble tennis in virtual reality. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies, 158:102731.

Rho, E., Chan, K., Varoy, E. J., and Giacaman, N. (2020).

An Experiential Learning Approach to Learning Man-

ual Communication Through a Virtual Reality Envi-

ronment. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technolo-

gies, 13(3):477–490. Conference Name: IEEE Trans-

actions on Learning Technologies.

Wu, E., Nozawa, T., Perteneder, F., and Koike, H. (2020).

VR Alpine Ski Training Augmentation using Visual

Cues of Leading Skier. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Con-

ference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition

Workshops (CVPRW), pages 3836–3845. ISSN: 2160-

7516.

Zhao, Y. (2022). Teaching traditional Yao dance in the

digital environment: Forms of managing subcultural

forms of cultural capital in the practice of local cre-

ative industries. Technology in Society, 69:101943.

Building Suitable Observation Points to Enhance the Learner’s Perception of Information in Virtual Environment for Gesture Learning

435