Job Crafters Going Digital: A Framework for IT-Based Workplace

Adaption

Angelina Clara Schmidt

a

, Michael Fellmann

b

and Jakob Voigt

Institute of Business Informatics, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

Keywords: Job Crafting, Job Crafting Information Systems, Work Design, Workplace Wellbeing.

Abstract: The changing world of work is leading more and more people to reflect on the meaning and organization of

their work. Increased flexibility allows individuals to define and shape their own jobs. However, adapting

one’s job, which is referred to as job crafting, is a challenging manual task since many variables can be

modified with unclear dependencies. Hence, to systematically promote job crafting behaviors, Job Crafting

Information Systems (JCIS) were proposed a decade ago. However, up to now, it is highly unclear which IT-

supported interventions could be implemented in such systems. Against this gap, we develop an integrated

model that matches the different job crafting behaviors discussed in the literature with supporting and

facilitating IT components. As a result of our literature review, we include the functional IT components

recommendation, coaching, time management, and complaint management and identify gamification,

simplification, prediction, and integration as important non-functional characteristics of JCIS.

1 INTRODUCTION

In a changing society shaped by globalization and

digitalization, where individual and personal values

are becoming increasingly important, the world of

work is also changing. As a result, more and more

people are beginning to reflect on the meaning and

organization of their work. In recent years, the

number of self-employed and employees with

flexible, more individualized working conditions has

increased (Jent & Janneck, 2016).

With increasing flexibility, work boundaries,

meaning of work, and work identities no longer

entirely determined by formal work requirements,

employees have the freedom to define their jobs

themselves (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). People

with individualized working conditions often receive

less support from colleagues and supervisors. Thus,

the planning of work tasks, ergonomic workplace

design as well as structuring of working time, breaks,

and leisure time are shifting towards the individuals’

responsibility (Jent & Janneck, 2016). In this regard,

the work tasks and social interactions become the

‘raw material’ out of which employees construct their

jobs (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6967-4287

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0593-4956

This predominantly employee-driven way of

reconstructing job design, also known as job crafting,

offers a unique perspective on job redesign theory.

Traditionally, job design or redesign has been seen as

a top-down process where the organization creates

jobs and selects people with the appropriate

knowledge, skills, and abilities for those jobs. The

supervisors have been solely responsible for changing

tasks or roles. In contrast to this job crafting offers an

alternative bottom-up approach at the individual level

(Tims & Bakker, 2010). Without diminishing the

significance of the general organizational top-down

design (Peng, 2018), job crafting creates an

employee-centred, bottom-up concept with great

potential, e.g., to better accommodate an individual’s

preferences for working pace, place, and space for

strength-use and long-term stress reduction. It differs

from earlier concepts in that it focuses on proactive

changes in job design that do not have to be

negotiated as specific arrangements with the

organization (Tims & Bakker, 2010), and in this

sense, can be considered as an approach for the ex-

post adaptation of the job. Although it is discussed

that job crafting can be formally approved or

unapproved (Berg et al., 2008), the different typical

Schmidt, A., Fellmann, M. and Voigt, J.

Job Crafters Going Digital: A Framework for IT-Based Workplace Adaption.

DOI: 10.5220/0012689200003690

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024) - Volume 2, pages 703-712

ISBN: 978-989-758-692-7; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

703

forms of job crafting are usually not even noticed by

the supervisor (Tims & Bakker, 2010) (sometimes

also referred to as “bottom-up leadership”).

Based on the definition of a job as a collection of

tasks and interpersonal relationships assigned to a

person in an organization (Berg et al., 2008), there are

different dimensions that characterize job crafting.

Generally, the sum of all the resulting physical and

cognitive changes that individuals make to the task or

relationship boundaries of their work is referred to as

job crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Another

approach postulates that employees take individual

action to counteract the imbalance between stressful

work demands (their costs) and compensating work

resources (their benefits) by proactively shaping the

characteristics of their jobs and tasks (Tims &

Bakker, 2010). In this way, job crafting is an activity,

and those who execute it, also called job crafters,

read, interpret, and modify cues to the boundaries of

work (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Though these

activities may be performed as a continuous process

(Peng, 2018), job crafting does not explicitly involve

only long-term solutions. It can also occur in a short-

term form (Tims & Bakker, 2010) and complements

the material rewards of work with intangible rewards

such as well-being or personal values (Peng, 2018).

However, executing job crafting is inherently

complex and challenging since many interdependent

variables may be modified, such as one’s pace of

work (e.g., rapid progress in a single project or multi-

tasking), place of work (e.g., remote or onsite) or

space of work (e.g., used files and folders, tools or

rooms).

IT-supported interventions offer the opportunity

to improve the productivity and health of employees.

In the direction of job crafting, so-called Job Crafting

Information Systems (JCIS) were proposed a decade

ago (Kehr et al., 2014) as a way to promote job

crafting behaviors systematically. To do so, they

should be tailored to strengthen the individual’s

ability to shape their working environment, e.g., to

improve strength-use or alleviate causes of stress. By

applying high-scalable and cost-efficient solutions,

employees' individual health, productivity, and

overall organizational performance could be

improved (Kehr et al., 2014). These are usually based

on findings from the theoretical foundations of

psychology and the behavioral sciences (Xu et al.,

2018). However, concrete implementations of JCIS

are still rare, as the focus so far has been on clarifying

the requirements and overarching abstract principles

of such systems (Kehr et al., 2014). What is greatly

lacking is a set of concrete features for such systems

that could inform the creation of dedicated JCIS

systems or the extension of existing enterprise

systems with JCIS features. Against this research gap,

we analyze how research activities have developed

since the introduction of the job crafting concept,

which behaviors constitute job crafting, how job

crafting behaviors can be supported and promoted by

IT-supported interventions, and which perspectives

and limitations of IT support exist. Based on a

literature analysis, we present an integrated model

that correlates the different behaviors discussed in the

literature with the existing supporting and facilitating

IT components. We hope that our model will inform

and inspire the addition of JCIS features to existing

enterprise systems as well as the development of

future JCIS systems.

2 JOB CRAFTING THEORIES

This paper examines the current state of research on

interventions and components for JCIS. Starting from

the general behaviors that constitute job crafting, the

aim is to find out how these are supported by IT or

how IT could support these behaviors. For this

reason, the fundamental theories of job crafting are

presented in this section, as they are essential for the

development of suitable IT systems. The different

theories are integrated into our model.

2.1 Original Job Crafting Theory

Wresniewski and Dutton define job crafting as the

physical and cognitive changes and actions that

individuals take at the task or relationship boundaries

of their work to shape, form, or redefine their jobs

(Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Job crafting is

divided into task, cognition, and relationship

crafting. Task crafting describes changes in task

boundaries, for example, by adjusting the form or

number of tasks or activities. Cognition crafting, on

the other hand, focuses on shifts in cognitive work

boundaries, i.e., how work is viewed. Relationship

crafting refers to adjusting relationship boundaries

and interactions with others at work. These actions

influence work meaning, as the individual’s

understanding of the purpose of their work and work

identity, as well as the way individuals define

themselves at work (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

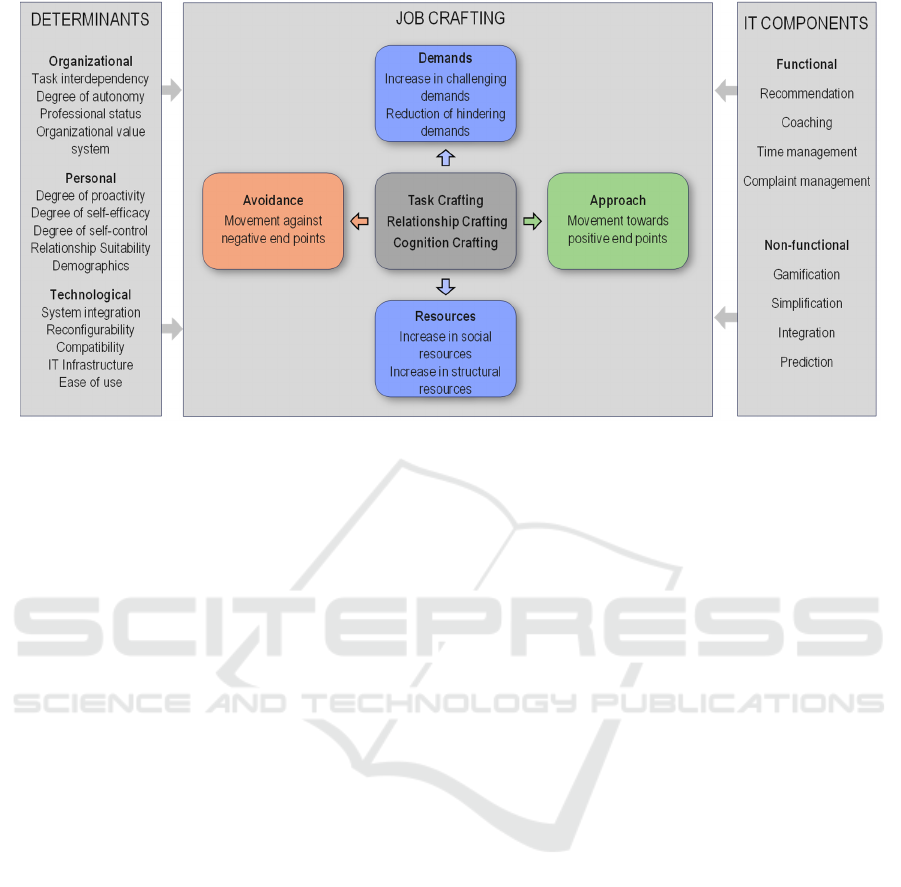

Figure 1 shows the methods that can be used to

perform the different subforms of crafting. These

methods are included as the core of our model.

Task crafting is characterized by changes in the

type of work tasks, the task domain, or the number of

work tasks (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). The way

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

704

work tasks are performed is also important (Berg et

al., 2008). Relationship crafting can be done by

changing the quality or quantity of relationship

interactions and adjusting the interaction partners and

one's own interaction being (Wrzesniewski & Dutton,

2001). In addition, the frequency of interaction can be

adjusted (Tims & Bakker, 2010). Cognition crafting

aims to create a changed view of work as individual

parts or as an integrated whole (Wrzesniewski &

Dutton, 2001). Reflection on the work situation (Kehr

et al., 2014) as well as the inner reorientation of the

social purpose of work to include personal passions

(Berg et al., 2008) can lead to changes in the personal

perspective.

Figure 1: Core of the model.

2.2 Demand Resource Theory

A completely different approach than the original

theory is taken by the representatives of the demand-

resource (DR-)theory. First described by Tims and

Bakker in 2007, this theory assumes that job crafting

is a specific form of proactive behavior in which

employees initiate changes in work demands and

work resources (Tims & Bakker, 2010). The founders

of this theory also see the approach as a form of cost-

benefit analysis in which employees take individual

actions to strike a balance between more burdensome

demands resp. costs and more compensating

resources resp. benefits (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Work demands are physical, social, or organizational

aspects of work that require constant effort (Lee et al.,

2018). The counterpart to this, work resources, are all

the means that help the individual achieve the desired

work goals (Lee et al., 2018). The goal is to minimize

stress-increasing work demands, increase stress-

reducing ones, and expand one’s own work resources.

According to Tims and Bakker, job crafting can

be divided into four categories based on work

demands and resources (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

These include (i) the increase of (challenging) work

demands, (ii) the reduction of hindering work

demands, (iii) the increase of social work resources,

and (iv) the increase of structural work resources

(Tims & Bakker, 2010). Challenging work demands

are those that challenge and fulfill the employee

positively. On the other hand, obstructive or

hindering work demands are often externally defined

demands that interfere with or disrupt the employee’s

work in an unpleasant way. Social work resources are

all of the employee's social skills and abilities that

they can use to achieve their work goals. Structural

work resources, on the other hand, are all the material

or technological aids that help to achieve goals.

2.3 Approach Avoidance Model

Due to the widespread acceptance of the theories

described so far, there have been few additional

attempts to categorize or describe job crafting

behavior. One approach that combines the two most

common theories is the approach-avoidance model

proposed by Zhang and Parker (Zhang & Parker,

2019). It derives from Andrew Elliot's theory of

approach-avoidance motivation, which is widely

accepted in the behavioral sciences and suggests that

people tend to move towards positive end points and

against negative end points (Elliot, 2006). Movement

against a positive end point represents approach

behavior and is approach-motivated. Movement

towards a negative end point, on the other hand,

represents avoidance behavior and is therefore

avoidance-motivated.

A first attempt to build on this theory was the so-

called role-resource-avoidance approach by Bruning

and Campion (2018), which is a combination of the

role-resource theory (or demand-resource theory) and

the approach-avoidance approach but does not

include the original theory by Wrzesniewski and

Dutton (Bruning & Campion, 2018). This theory

classifies job crafting behaviors along two

dimensions, each with distinct characteristics. The

first dimension ranges from role (or demand) to

resource crafting. The second dimension ranges from

approach to avoidance crafting. The different

manifestations of job crafting can now be classified

by allocating the different sectors between approach

and demand, avoidance and demand, approach and

resources or avoidance and resources. From their

Task Crafting

Relationship Crafting

Cognition Crafting

Changing the type of tasks

Changing the number of tasks

Changing the approach

Moving the task area

Expand the task role

Changing the quality of the working relationship

Changing the quantity of the working relationship

Changing the frequency of interaction

Changing the persona of interaction

Changing the art of interaction

Consideration of work as integrated single entity

Consideration of work as individual parts

Changing the personal perspective

Job Crafters Going Digital: A Framework for IT-Based Workplace Adaption

705

position, it can be deduced whether each behavior is

more need- or resource-oriented and if it represents

an approach or avoidance behavior.

In contrast to Bruning and Campion, Zhang and

Parker’s model also incorporates the original theory,

thus providing a holistic approach. Approach and

avoidance crafting function as two distinct

overarching constructs, resulting in a model with

three hierarchical levels (Zhang & Parker, 2019). The

first level includes job crafting orientation and

distinguishes between approach and avoidance

(Zhang & Parker, 2019). The second level concerns

the form of job crafting and, according to the original

theory, distinguishes between task crafting,

relationship crafting, and cognition crafting (Zhang &

Parker, 2019). The third level describes the job

crafting content and distinguishes between demands

and resources (Zhang & Parker, 2019). The idea

behind this is that each job crafting behavior fulfills

exactly one characteristic at each level and can thus

be clearly categorized.

3 IT SUPPORT FOR JOB

CRAFTING

Research in the area of job crafting has so far mainly

focused on clarifying the theoretical foundations,

requirements, and abstract overarching design

principles, while concrete implementations are

lacking (Kehr et al., 2014) (cf. also Section 2).

Therefore, in the following we exemplary present few

existing JCIS and then analyze which components

already used in other systems can be additionally

adapted for enriching existing systems with JCIS-

features or to create dedicated JCIS.

3.1 Literature Analysis

The research team has analyzed the literature using

the databases Scopus and AIS eLibrary. As search

terms, we used “job crafting” and combined it with

“information system” or “IT system”, “software” and

other variants denoting IT. The search delivered 42

results in AISeL and 91 results in Scopus, whereby

nine results have occurred in both databases. The

result set of 124 sources was further sorted. Sources

written in English or German were included. Due to

the strong overlap with disciplines such as

psychology, sociology, and behavioral sciences,

articles that were more concerned with psychological

studies on the causes and consequences of job

crafting and focused on the connection with

behavioral or personality-related variables were

excluded. We included articles that specifically focus

on developing JCIS as well as articles that investigate

the influence of other IT tools on job crafting. As a

result, 15 articles were identified as relevant for our

context, which will be described in the following.

From 2014 onwards, job crafting research with a

growing relevance of IT and JCIS began. In their

research-in-progress works Kehr et al. identified the

need for validated design principles for JCIS (Kehr et

al., 2013) and started to develop an evaluation model

(Kehr et al., 2014). Continuous, repeated use of JCIS

seems to be fundamental for the effectiveness of the

app (Kehr et al., 2014).

One attempt to support job crafting through IT is

the Job Crafting Coach by Jent and Janneck: An

online coaching application with gamification

elements. The extent to which these elements

promote user motivation was investigated (Jent &

Janneck, 2016). Gamification is the use of game

design elements in non-game contexts to increase

user motivation and activity (Jent & Janneck, 2016).

The application aims to educate users about the

benefits of job crafting through various lessons, some

of which can be unlocked, and to support this with

gamification elements (Jent & Janneck, 2016).

However, the analysis of the system is reduced to the

influence of the gamification elements and less to the

overall technological design of the software.

Important findings of the study are that the elements

indeed had varying degrees of influence on learning

success and supported continuous use of the

application (Jent & Janneck, 2016). It can be deduced

from this that those elements successfully used on

educational platforms are also suitable for JCIS (Jent

& Janneck, 2016). While some gamification elements

proved to be beneficial and popular, others had a less

positive effect. For example, countdowns seem rather

unsuitable as they create time pressure and stress and

thus counteract the actual goals of the applications

(Jent & Janneck, 2016). The same applies to ranking

lists, which create social pressure (Jent & Janneck,

2016). On the other hand, elements such as progress

bars, badges, unlocking exercises, and a score

accumulation system were rated positively (Jent &

Janneck, 2016). In addition, study participants

indicated that they would also feel motivated by

quizzes or a star rating system, but not by a tip of the

day or a badge for using the app on consecutive days

(Jent & Janneck, 2016). It can be concluded that

gamification, as in other applications, can play an

important role in the design of JCIS.

The effectiveness of an electronic job crafting

intervention via an electronic learning environment,

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

706

which aims to stimulate task, relationship, and

cognition crafting, was examined by (Verelst et al.,

2021). The design of an e-job crafting intervention is

supposed to be usable as well as persuasive to reach a

good adherence (Verelst et al., 2021).

Apart from the aforementioned approaches, the

remaining literature did not aim to develop a JCIS but

provides interesting insights regarding the interplay

between IT and job crafting. IT is a key factor in the

recent revival of job crafting (Lee et al., 2018).

Xu et al. integrate job crafting and proactive

behavior theories to conceptualize the antecedents of

collaborative job crafting (Xu et al., 2018). Therefore,

they highlighted technological characteristics (e.g.,

technological reconfigurability, system integration)

as important elements that impact employees’

motivational states, which subsequently affect

collaborative job crafting (Li et al., 2022). In another

study, Xu et al. show that IT can increase work

meaningfulness if the characteristics of the

technologies include reconfigurability and

customization to enable employees to redesign their

jobs (Xu et al., 2023). Technology reconfigurability

describes how a user perceives that IT is implemented

in a way that enables the adaption of IT features

during use (Xu et al., 2023), whereas customization is

the way that the system meets the users’ functional

needs of the user to perform tasks (Xu et al., 2023).

Research started to investigate “adoption job

crafting”, meaning “the active and goal-directed use

of technology and other sources of knowledge to alter

the job and enhance a work process” (Bruning &

Campion, 2018), e.g., automating tasks to reduce

potential errors (Mansour & Nogues, 2022). In doing

so, workload reduction could increase opportunities

for task-enhancing job crafting (Mansour & Nogues,

2022), e.g., alter the time or energy spent on tasks,

drop old or add new tasks, or change the nature of

tasks (Berg et al., 2013).

The findings of Mansour and Nouges suggest that

the adoption of new technology is highly dependent

on the level of supervision and technical maintenance

devoted to the new technology (Mansour & Nogues,

2022). To avoid creating additional problems and

workload, employees should not be too involved in

the maintenance of the software (Kehr et al., 2013).

Users adopt technology that helps them to do their job

(Lee et al., 2018), when it can improve work

performance without much effort (Kehr et al., 2013).

A qualitative pilot study by Gennaro et al.

examined the effect of work digitalization and

information and communication technology (ICT) on

job crafting by exploring public sector workers’

attitudes towards technology through semi-structured

interviews. This study provides indications that

individual attitudes are significant drivers of the job

crafting process. The workers who have a positive

attitude towards technology are the ones who modify

their jobs (Gennaro et al., 2022). Perceptions of utility

and ease of use influence attitudes (Gennaro et al.,

2022), further highlighting the importance of these

aspects for new systems.

Lee et al. examine, among other things,

compatibility and actual use as characteristics of

technology. Their field survey data indicates that

these characteristics appear to shape the individual

job crafting behavior. Compatibility means that

technology can only be used well if the features

support what the users need to execute their tasks

(Lee et al., 2018), which is in line with the definition

about technology customization mentioned before.

Furthermore, IT can only be influential if it is actually

used (Lee et al., 2018).

Apart from that, Blazejewski and Walker explore

a potentially critical aspect of digitalization: they seek

to understand job crafting practices when

digitalization processes might reduce perceived

autonomy through an empirical organizational case

study of the introduction of a new system in a retail

group. Their results show that employees try to

reduce their digital work stress by attributing a

function to the technological system in use that does

not conflict with their professional self-perception

(Blazejewski & Walker, 2018).

According to Batova’s research, the motivation to

use a component content management system also

increased when users were motivated to do job

crafting (Batova, 2018). Consequently, job crafting

and a potential JCIS can also positively impact user

activity in other systems. It is also known from the

use of customer relationship management systems

that job mechanisms can work in existing systems

(Xu et al., 2018). For example, employees can change

their schedule, focus on clients and tasks that yield

high returns or minimize stress, or rate tasks and

clients with different levels of importance and

urgency (Jent & Janneck, 2016). It can be deduced

from this that those components already integrated

into an existing corporate infrastructure system could

also be adapted for a potential JCIS.

ICT can be used to increase job resources and

tackle job demands, increasing overall occupational

well-being (Tarafdar & Saunders, 2022). Tarafdar

and Saunders conceptualize and define “ICT-enabled

job crafting as the use of ICT to shape the task,

relational, and cognitive aspects of work” (Tarafdar

& Saunders, 2022). Peters et al. showed that low-code

development platforms enable job crafting forms for

Job Crafters Going Digital: A Framework for IT-Based Workplace Adaption

707

business unit developers as an example of ICT-

enabled job crafting (Li et al., 2022). Moreover, being

able to “bring your own device” is expected to have

an influence on job crafting (Wang et al., 2018).

Electronic human resource management can also be a

stimulus for employee initiative (Zhou et al., 2021).

Summarizing the results so far, research on

dedicated JCIS is very scarce and JCIS are still an

(almost) non-existent category of enterprise systems.

Therefore, it seems to be more promising to analyze

the literature for relevant functional IT components

that could be used to extend existing enterprise

systems with JCIS-features or to build dedicated JCIS

and which non-functional characteristics should be

considered in system design (cf. Section 3.3).

3.2 Barriers and Influences

Nowadays, job crafting is known to be practiced in a

variety of organizations and professions (Berg et al.,

2008). However, whether an employee can engage in

job crafting depends on various influencing factors.

These are determined either by the structure of the

organization and the task design, by the technical

possibilities of the organization, or by the personality

of the employee.

Wrzesniewski and Dutton suggest that economic

constraints give or deny individuals with different

personal resources the opportunity to evaluate,

interpret, and act within job categories (Wrzesniewski

& Dutton, 2001). For example, differences in

professional status, standards and requirements, as

well as organizational values, beliefs and norms, may

influence the ability to engage in job crafting

(Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Among the most

frequently mentioned job characteristics in the

literature that have a significant influence on job

crafting are the degree of task interdependence and

the degree of autonomy (Tims & Bakker, 2010;

Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Zhang & Parker,

2019).

The lower the interdependence of tasks and the

less complex the task profile of the organization, the

more likely it is that job crafting is possible. The same

applies to the degree of autonomy. The higher the

degree of autonomy granted to the employee, the

greater the possibilities for job crafting. Other

organizational aspects that can influence employees'

job crafting behavior are workload, work resources

and demands, and the manager’s leadership style

(Zhang & Parker, 2019).

In addition to these organizational aspects, the

personality of the employee plays a crucial role.

There are several personality traits that favor the

adoption of job crafting behaviors. In particular,

proactive personality is considered to be a good

predictor of job crafting (Parker et al., 2010; Peng,

2018; Tims & Bakker, 2010; Zhang & Parker, 2019).

Proactive behavior in this context means getting

things done, anticipating and avoiding problems or

seizing opportunities when they arise (Parker et al.,

2010).

Besides proactive behavior, there are other

personality-related predictors of job crafting. These

include, for example, self-efficacy and self-control

(Tims & Bakker, 2010). Demographic parameters

such as age can also influence behavior (Jent &

Janneck, 2016). In addition, the individual need for a

positive self-image, work experience and human

connection play a role (Niessen et al., 2016).

Extroversion, openness, psychological capital, work

engagement and organizational involvement are also

mentioned in the literature as positive influencing

factors (Zhang & Parker, 2019).

Besides these more facilitating personality traits,

however, there are also less facilitating traits. For

example, employees who already suffer from

burnout, depression or excessive demand on their

work role engage in significantly less job crafting

(Zhang & Parker, 2019). Furthermore, it is

conceivable that demographic parameters such as age

also have a negative influence here (Jent & Janneck,

2016). Neuroticism is also mentioned as a negative

factor (Zhang & Parker, 2019).

In addition to the organizational and personality-

related aspects, the technological environment is also

becoming increasingly relevant as digitalization

progresses. Through the literature review described in

section 3.1, the following factors could be identified.

The organization’s internal IT-infrastructure and

certain IT characteristics play a decisive role here.

Key IT characteristics include reconfigurability,

system integration (Xu et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2023),

compatibility (Lee et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2023) and

ease of use (Gennaro et al., 2022).

A more flexible, quickly reconfigurable, and

integrative IT system offers employees more

opportunities for job crafting, e.g. by adjusting

settings. The better an organization's various IT

systems are integrated, the smoother work processes

involving several people will run. An adaptable

design of the IT landscape is also of central

importance with regard to the integration of JCIS.

Which approaches for JCIS already exist and how a

JCIS should be designed is discussed in the following.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

708

Figure 2: Integrative job crafting model.

3.3 Analysis of IT Components

Based on the identified literature (cf. Section 3.1),

several workshop meetings among the author team

were conducted to elicit relevant components based

on the findings in the literature. Based on the

discussions in the meetings, four possible functional

IT components of JCIS emerged, which we explain in

the following:

• Recommendation

• Coaching

• Time Management

• Complaint Management

As a proactive component, the recommendation

system should make suggestions to the user based on

his or her usage activity. For example, appropriate

work items could be recommended that match the

users’ preferences or strengths. It could also

recommend a particular task or the appropriate

number of people to complete a task. This way,

appropriate recommendations may also nudge less

proactive users to engage in job crafting.

Furthermore, it should be possible to predict the

perceived stress of a task so that the application can

suggest a balanced repertoire of tasks to the user.

The coaching component helps to raise awareness

and provide training. The client should learn which

job crafting behaviors exist and how to use them to

gain an advantage. Furthermore, the client should

learn how to train their cognitive mindset and the

methods available to reduce stress at work. The

learning should take place in different lessons, similar

to the Job Crafting Coach developed by Jent and

Janneck.

The time management component, in line with the

insights gained in the context of customer relationship

management systems and similar systems (cf. Section

3.1), ensures that employees have a higher degree of

autonomy in managing their time. In this context,

time management means both free organization and

time tracking. The aim is therefore to be able to freely

allocate and document the time spent on different

projects, but also to use the recommendation system

to warn the user if they are working too much

overtime.

Also derived from customer relationship

management is the complaint management

component. This is intended to let the user

communicate concerns and problems within the

organization, in order to proactively eliminate

obstructive demands.

The identified functional components should

operate as a combined unit rather than as independent

sub-systems, thus supporting each other. Ideally, the

user should not be able to distinguish which

component or sub-system is currently being used. In

addition, the JCIS as a whole should adhere to certain

non-functional characteristics that have been shown

to be beneficial. To this end, we identify four main

non-functional characteristics:

• Gamification

• Simplification

• Prediction

• Integration

Job Crafters Going Digital: A Framework for IT-Based Workplace Adaption

709

Jent and Janneck have already been able to

demonstrate the benefits of gamification (Jent &

Janneck, 2016). These seem essential for a system

that is supposed to improve the work design of

employees to ensure high user satisfaction, adequate

user activity and positive long-term effects.

Simplification should also be applied. A JCIS should

be as detailed as necessary, but as simple as possible

to avoid overwhelming users. Moreover, a JCIS

should also have a predictive character and identify

the needs of the customer as proactively as possible

(prediction). This is particularly necessary for the

recommendation components. Finally, a JCIS should

have a high degree of technical embeddability and

integrability. If possible, it should be able to be

integrated into the company’s existing IT

infrastructure, run on the most common operating

systems or even be executable as an add-on in other

software.

Figure 2 summarizes the previous findings in an

integrative model. The organizational, personal and

technological influencing factors (cf. Section 3.2) are

shown on the left and the influencing IT components

on the right. Both sides act as drivers for the

implementation of job crafting. In the center is an

overview of all the possible job crafting methods that

could be adopted by the employee. Our approach is

that avoidance and approach are not superordinate

constructs, but that different job crafting methods are

complementary. At the core of the model are the

behaviors identified in the original theory. Starting

from this core, the work demands and resources are

adjusted using a wide variety of methods. These can

be changed through task crafting, relationship

crafting or cognition crafting. In addition, the

different methods of job crafting (including demand

crafting and resource crafting) may represent a

tendency towards avoidance or approach behavior,

which we will show in the following section.

3.4 Mapping

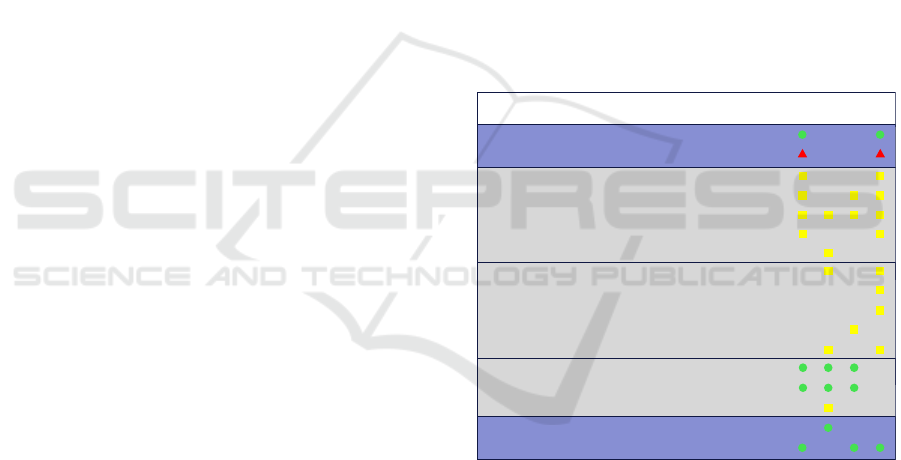

Figure 3 shows the influence of the IT components on

the different job crafting methods in the form of a

matrix. For this purpose, the IT components are

transferred to the matrix: Recommendation (R),

Coaching (C), Time Management (TM) and

Complaint Management (CM). Different symbols are

used to illustrate whether one of the IT components

has the potential to support the respective job crafting

method (symbol) or not (no symbol). In addition, a

traffic light rating system indicates whether the

respective support is more of an approach behavior

(green circle) or an avoidance behavior (red triangle)

or whether the method shows forms of both variants

(yellow square). All assignments have been made by

the authors individually and discussed later on in

workshops until a consensus was reached.

When looking at Figure 3, it is obvious that most

methods of job crafting can be considered both as an

approach and an avoidance behavior. Depending on

the direction in which one adjusts, for example, the

number of tasks or work relationships, the job crafter

can avoid tasks or work relationships or approach

new ones. On the other hand, viewing work as an

integrated whole or as individual components,

increasing challenging demands and any form of

resource crafting represent approach behavior in each

case. The only purely avoidance behavior identified

was the reduction of hindering work demands. This

means that for most behaviors, it is up to the job

crafters if they prefer more approach-orientation or

avoidance-orientation. This emphasizes the

importance of a recommendation approach sensitive

to the users’ preference for approach or avoidance

styles of job crafting behaviors.

Figure 3: Influence of IT components in matrix

representation.

Key: R=recommendation, C=coaching, TM=time mgmt.,

CM=complaint mgmt.

3.5 Perspectives and Limitations

Implementing job crafting programs requires highly

qualified workplace and health specialists (Kehr et

al., 2014), which is why JCIS are not widespread in

practice. For this reason, there are currently only a

small number of prototypes or systems, as

development requires highly qualified specialists

from several disciplines.

Job Crafting Method

Increase in challenging demands

Reduction of hindering demands

Changing the type of tasks

Changing the number of tasks

Changing the approach

Moving the task area

Expand the task role

Changing the quality of the working relationship

Changing the quantity of the working relationship

Changing the frequency of interaction

Changing the persona of interaction

Changing the art of interaction

Consideration of work as integrated single entity

Consideration of work as individual parts

Changing the personal perspective

Increase in social resources

Increase in structural resources

RCTMCM

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

710

The use of job crafting methods in general, and

thus also the use of supporting IT systems, is limited

by the organizational, personal, and technological

factors shown in Figure 2. In particular, relationship

crafting as a subcategory of job crafting could

become a challenge for IT systems, as it is mainly

supported by the complaint management system in

the method matrix (Figure 3) and less by several IT

components at the same time.

In general, besides the multitude of positive

consequences, it should be noted that job crafting can

also have negative consequences. These include, for

example, additional stress (Berg et al., 2008), which

can be triggered if the application of JCIS is perceived

as a constraint or even as overwhelming. The use of

such programs should therefore be voluntary.

Negative consequences may include intentions to

switch jobs due to dissatisfaction with the new system

and increased workload, even burnout (Zhang &

Parker, 2019).

On the other hand, job crafting can positively

influence work engagement, job satisfaction, and job

performance (Tims & Bakker, 2010). The

meaningfulness of work, identification with work,

and individual well-being can be strengthened (Peng,

2018; Tims & Bakker, 2010). Furthermore, there is

evidence that job crafting is positively related to

person-job fit (Niessen et al., 2016) and can impact

creativity, personal growth and the development of

personal competences. Therefore, the goal should be

to promote the many positive effects of job crafting

and avoid negative effects (Berg et al., 2008). This

should be taken into account when developing

suitable IT systems.

4 CONCLUSION

So far, only a few approaches offer IT support for job

crafting, despite the term of JCIS has been coined

almost a decade ago. The research field focuses

primarily on the description of job crafting behavior

and the underlying personality and environmental

factors that promote such behavior. In doing so, the

theory was further developed from the distinction

between task crafting, relationship crafting, and

cognition crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001)

and the demand resource approach (Tims & Bakker,

2010) into a synthetic model that also includes the

categories of avoidance and approach (Zhang &

Parker, 2019).

The focus of IT support is currently mainly on the

aspect of gamification. In addition, other supporting

IT components such as recommender systems, time

recording systems, or complaint management

systems can be implicitly derived. Still, concrete

implementations or prototypes are missing in the

literature.

Furthermore, it is conceivable that components

that cannot be derived from the literature, such as

knowledge management systems, are also suitable for

IT support of job crafting. Moreover, it seems

possible that there are implementations of job crafting

that are on the market but not discussed in the

scientific literature. Knowledge about such

components and systems could close knowledge gaps

about the value proposition of JCIS and provide

further approaches to how a JCIS should be designed.

Based on the findings, an integrative model was

developed, which follows the approach that the

different job crafting behaviors should not be

arranged in a hierarchical order but complement each

other. A job crafting behavior can belong to several

categories at the same time. The resulting model is an

initial proposal that may be expanded and discussed.

All in all, job crafting offers enormous potential

to make working life easier for employees and, by

extension, for employers and the entire organization.

The promotion of job crafting in the company, if

implemented correctly, offers a suitable approach to

reduce the stress of employees and, indirectly, to

increase the company's profit in the long run.

However, further research seems necessary to

identify the value contribution of such systems. This

also includes the development of prototypes and the

required tests. The main barriers to development

mentioned are the high development costs due to the

high demand for specialists. Furthermore, although

awareness of the social and economic benefits of

sound occupational health management seems to be

growing, it is still low at the societal and

organizational level.

REFERENCES

Batova, T. (2018). Work Motivation in the Rhetoric of

Component Content Management. Journal of Business

and Technical Communication, 32(3), 308–346.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651918762030

Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2008). What

is job crafting and why does it matter. Purpose and

Meaning in the Workplace.

Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job

crafting and meaningful work. In B. Dik, Z. S. Byrne,

& M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the

workplace (pp. 81–104). American Psychological

Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14183-005

Job Crafters Going Digital: A Framework for IT-Based Workplace Adaption

711

Blazejewski, S., & Walker, E.‑M. (2018). Digitalization in

Retail Work: Coping With Stress Through Job Crafting.

management revu, 29(1), 79–100. https://doi.org/

10.5771/0935-9915-2018-1-79

Bruning, P. F., & Campion, M. A. (2018). A Role–resource

Approach–avoidance Model of Job Crafting: A

Multimethod Integration and Extension of Job Crafting

Theory. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 499–

522. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0604

Elliot, A. J. (2006). The Hierarchical Model of Approach-

Avoidance Motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 30(2),

111–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9028-7

Gennaro, D. de, Adinolfi, P., Piscopo, G., & Cavazza, M.

(2022). Work Digitalization and Job Crafting: The Role

of Attitudes Toward Technology. In (pp. 59–72).

Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-

86858-1_4

Jent, S., & Janneck, M. (2016). Using Gamification to

Enhance User Motivation in an Online-coaching

Application for Flexible Workers. In Volume 2:

WEBIST 2016 (pp. 35–41). https://doi.org/10.5220/000

5898400350041

Kehr, F., Bauer, G., Jenny, G., Güntert, S. T., & Kowatsch,

T. (2013). Towards a Design Model for Job Crafting

Information Systems Promoting Individual Health,

Productivity and Organizational Performance.

Kehr, F., Baür, G., Jenny, G., & Güntert, S. (2014).

Enhancing Health and Productivity at Work: towards an

Evaluation Model for Job Crafting Information

Systems. ECIS 2014 Proceedings.

Lee, J., Lee, H., & Suh, A. (2018). Information Technology

and Crafting of Job: Shaping Future of Work? PACIS

2018 Proceedings, 275.

Li, M. M., Peters, C., Poser, M., Eilers, K., & Elshan, E.

(2022). ICT-enabled job crafting: How Business Unit

Developers use Low-code Development Platforms to

craft jobs. ICIS 2022 Proceedings, 16.

Mansour, S., & Nogues, S. (2022). Advantages of and

Barriers to Crafting New Technology in Healthcare

Organizations: A Qualitative Study in the COVID-19

Context. International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, 19(16). https://doi.org/

10.3390/ijerph19169951

Niessen, C., Weseler, D., & Kostova, P. (2016). When and

why do individuals craft their jobs? The role of

individual motivation and work characteristics for job

crafting. Human Relations, 69(6), 1287–1313.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715610642

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making

Things Happen: A Model of Proactive Motivation.

Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363732

Peng, C. (2018). A Literature Review of Job Crafting and

Its Related Researches. Journal of Human Resource

and Sustainability Studies, 06(01), 1–7.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jhrss.2018.61022

Tarafdar, M., & Saunders, C. (2022). Remote, Mobile, and

Blue-Collar: ICT-Enabled Job Crafting to Elevate

Occupational Well-Being. Journal of the Association

for Information Systems, 23(3), 707–749. https://

doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00738

Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a

new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of

Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1–9.

Verelst, L., Cooman, R. de, Verbruggen, M., Laar, C., &

Meeussen, L. (2021). The development and validation

of an electronic job crafting intervention: Testing the

links with job crafting and person‐job fit. Journal of

Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(2),

338–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12351

Wang, W [Weian], Iyer, L., & Panigrahi, P. (2018). The

Impact of BYOD Use on Employees' Proactive

Behaviors: A Job Crafting Perspective. AMCIS 2018

Proceedings.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a Job:

Revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their

Work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–

201. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378011

Xu, M., Ou, C. X., & Wang, W [Wei] (2018). Information

technology-enabled collaborative job crafting in self-

leading team. PACIS 2018 Proceedings, 72.

Xu, M., Wang, W [Wei], Ou, C. X., & Song, B. (2023).

Does IT matter for work meaningfulness? Exploring the

mediating role of job crafting. Information Technology

& People, 36(1), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-

08-2020-0563

Zhang, F., & Parker, S. K. (2019). Reorienting job crafting

research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting

concepts and integrative review. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 126–146.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2332

Zhou, L., Chen, Z., Li, J., Zhang, X., & Tian, F. (2021). The

influence of electronic human resource management on

employee's proactive behavior: based on the job

crafting perspective. Journal of Management &

Organization, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.20

21.33

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

712