Business Process Improvements in Hierarchical Organizations:

A Case Study Focusing on Collaboration and Creativity

Simone C. dos Santos

a

, Malu Xavier

b

and Carla Ribeiro

Centro de Informática, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil

Keywords: Business Process Improvement, Collaboration, Creativity, Case Study, Hierarchical Organization.

Abstract: This paper describes a case study of business process improvement (BPI) in a large and hierarchical

organization in the public sector. Business Process Management (BPM) is crucial in the inevitable digital

transformation of large organizations, streamlining workflows and enhancing efficiency. It involves

systematic design, execution, and continuous improvement of processes, incorporating efficient activities and

digital tools like automation and artificial intelligence. Despite the benefits, implementing BPM in highly

hierarchical organizations poses challenges, including resistance to change and communication barriers. Thus,

the paper advocates a collaborative and creative BPI approach to address these as a crucial stage of the BPM

cycle. Collaboration is essential for breaking down silos and promoting a holistic BPM approach, while

creativity facilitates transformative change in established norms. From several BPI methodologies available,

we select and apply one called Boomerang in a collaborative workshop format. This methodology is based

on a design thinking process and gamification strategy. A case study utilizing Boomerang demonstrates

successful BPI by balancing established structures with innovative transformations. Still, lessons learned are

identified, emphasizing the need for careful preparation of a collaborative workshop, stakeholders’ selection,

a kit of artifacts to support this event, and a trained group to conduct the BPI process.

1 INTRODUCTION

Business Process Management (BPM) plays a

fundamental role in the digital transformation of large

organizations, optimizing and streamlining their

operational workflows (Pihir, 2019). At its core, BPM

involves the systematic design, execution,

monitoring, and continuous improvement of business

processes to increase organizational efficiency and

effectiveness (Brocke and Rosemann, 2015; Jeston

and Nelis, 2006). In large and hierarchical

organizations, easily found in the public sector, BPM

can help identify outdated or inefficient processes and

replace them with automated, technology-based

solutions (Ghatari et al., 2014). This may involve

integrating digital tools such as workflow

automation, artificial intelligence, and data analytics

to improve productivity and decision-making (Pihir,

2019). Moreover, BPM can promote collaboration

between departments, eliminating silos and

promoting a more cohesive approach to digitalization

(Pernici and Weske, 2006; Rosemann, 2015). By

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7903-9981

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-6835-4589

continually monitoring and analysing processes,

BPM allows organizations to identify areas for

improvement, ensuring that digital initiatives are

implemented and refined for continued success in the

ever-evolving digital landscape. Therefore, BPM is a

strategic driver that guides large organizations along

their digital transformation journey, driving

operational excellence and promoting a culture of

continuous improvement (Ahmad & Van Looy,

2020).

Despite these opportunities and benefits,

implementing BPM presents several challenges,

especially in large, highly hierarchical organizations.

Due to their complex structures and human-centric

and knowledge-intensive business processes, a

significant obstacle is resistance to change from

stakeholders involved in a BPM project since

hierarchical structures often establish entrenched

processes and organizational culture (Ghatari et al.,

2014). Convincing leaders to adopt BPM can be

complex, as it can disrupt existing power dynamics

and require a change in mentality that cannot always

Santos, S., Xavier, M. and Ribeiro, C.

Business Process Improvements in Hierarchical Organizations: A Case Study Focusing on Collaboration and Creativity.

DOI: 10.5220/0012697900003690

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2024) - Volume 2, pages 721-732

ISBN: 978-989-758-692-7; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

721

be achieved agilely (Looy, 2018). This complexity is

even more evident in the public sector, where

leadership positions are dynamic and periodic

(Ghatari et al., 2014). Siled departments may resist

sharing data, making creating integrated, streamlined

processes challenging. Furthermore, decision-making

processes can be slow and bureaucratic, preventing

the agility that BPM aims to achieve. Thus,

communication and collaboration barriers are

prevalent in hierarchical organizations, hindering the

continuous flow of information necessary for

effective BPM (Ghatari et al., 2014).

These challenges require change management

strategies, promoting a culture of openness to

innovation, and ensuring clear communication

channels (Looy, 2018). In this context, this article

defends an approach that stimulates the collaboration

and creativity of stakeholders involved in BPM

projects of hierarchical organizations, focusing on the

business process redesign and co-creation of the To-

Be model, a critical stage in business process

improvement (BPI) (Stojanović, 2016).

Collaboration and creativity are fundamental to

business process improvement (BPI) in large, highly

hierarchical organizations. In a context where rigid

structures and silos often prevail, promoting

collaboration is crucial to breaking down

communication barriers and promoting a holistic

approach to BPI, considering business and

technology sectors (Attaran, 2003). Furthermore,

cross-functional collaboration involving multiple

sectors and perspectives leads to more comprehensive

insights into existing processes and innovative

solutions for improvement with a broad view of

existing problems (Pernici and Weske, 2006). On the

other hand, creativity plays a central role in

identifying new approaches to streamline operations

and increase efficiency. Creative problem-solving

allows teams to think beyond traditional boundaries

and envision new, more effective processes (Figl &

Weber, 2012). Thus, in hierarchical organizations,

where adherence to established norms is common,

infusing creativity into BPI processes becomes a

catalyst for transformative change.

Several strategies can be employed to promote

collaboration and creativity within the BPI of these

organizations (Rosemann, 2015). Leadership must

actively encourage a culture of openness to ideas,

recognizing and rewarding innovative thinking.

Establishing cross-functional teams that bring

together individuals from different departments

promotes diverse perspectives (Cereja et al., 2018).

Creating a safe space for employees to express ideas

without fear of criticism encourages creative thinking

(Brown, 2009). Additionally, implementing

technology platforms for collaborative work and

sharing ideas facilitates communication and

engagement (Kock, 2005). By prioritizing these

aspects, large hierarchical organizations can navigate

the challenges of their structures and harness the full

potential of their workforce for successful business

process improvement.

This paper describes a case study that adopts a

combination of these alternatives through the

Boomerang Methodology defined in (Picanço &

Santos, 2022). Based on collaborative techniques,

design thinking methodology, and a gamification

strategy, this method was adapted and used in a BPM

Project of a large, highly hierarchical organization in

the judicial sector. The results prove the effectiveness

of this approach, showing that successful BPM in this

kind of organization requires a careful balance

between respecting established structures and driving

the transformations necessary to unlock efficiency

and innovation.

2 BPI METHODOLOGIES

Business Process Improvement (BPI) holds

significant importance within the Business Process

Management (BPM) cycle, contributing to enhanced

efficiency, effectiveness, and overall organizational

performance (Rashid & Ahmad, 2013; Smith, 2003;

Jeston and Nelis, 2006). BPI involves identifying,

analysing, and restructuring existing processes to

optimize outcomes. Integrating BPI into the BPM

cycle ensures a continuous and systematic approach

to managing and refining business processes.

Moreover, BPI fosters innovation and creativity. It

encourages a culture of continuous improvement,

empowering employees to contribute ideas for

process enhancement. This adaptability is crucial in

today's dynamic business environment, where

continuous changes require organizations to be

efficient and responsive.

BPI has two primary modalities (Stojanović,

2016): process redesign and reengineering. Process

redesign involves making incremental changes to

existing processes for optimization. In contrast,

process reengineering is more radical, requiring

fundamental restructuring to achieve significant

improvements. Both modalities aim to improve

operational performance to achieve substantial gains

in efficiency and effectiveness. Considering large and

hierarchical organizations, a BPM project usually

focuses on process redesign. So, the case study

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

722

discussed in Section 5 describes a public sector

experience in this context.

In general, there are several approaches to

carrying out a BPI initiative. Rashid & Ahmad (2013)

identifies and summarizes eight methodologies used

in BPI: MIPI (Model-Based Integrated Process

Improvement) Methodology, Super Methodology,

Benchmarking Methodology, PDCA (Plan-Do-

Check-Act) cycles, Lean Thinking, Six Sigma,

Kaizen, and TQM (Total Quality Management).

MIPI Methodology is a comprehensive approach

developed by Adesola & Baines (2005) to enhance

business process improvement in organizations. This

generic model comprises phases of understanding

business needs, modelling, and reviewing new

processes. It provides a hierarchical structure with

elements such as aim, actions, people involved,

checklists, and relevant tools. MIPI helps

organizations select and address the main barriers to

achieving their vision and mission, aligning with

business needs. Its generic nature may lead to

limitations in addressing specific industry nuances.

The hierarchical structure, while providing guidance,

may also introduce complexity. The Super

Methodology proposed by Lee and Chuah (2001)

combines continuous process improvement (CPI),

business process reengineering (BPR), and

benchmarking (BPB). This approach recognizes that

not all organizations can benefit from each, and a

combination may be more suitable. The Super

Methodology focuses on process selection,

understanding, measurement, execution, and

reviewing, aiming to make significant improvements,

particularly in small to medium-sized companies. The

Benchmarking Methodology involves continuously

comparing an organization's strategy, products, and

processes with those of successful counterparts

(Dragolea & Cotirlea, 2009). Originating in Japan in

the 1950s, it aims to adapt successful practices and

ideas to reduce costs and cycle time and enhance

competitive positioning. The methodology includes

planning, analysis, integration, actions, and maturity

phases, with internal and external benchmarking. The

PDCA Methodology is a continuous improvement

cycle developed by Walter Shewhart and popularized

by Dr. W. Edwards Deming (Sokovic, 2010). It

consists of four phases that emphasize accurate

planning, incremental implementation, measurement,

and feedback. PDCA is widely used in developing

and deploying quality policies within organizations.

Lean Thinking, originating in Toyota, focuses on

reducing waste to improve business performance. The

methodology involves sorting, straightening,

scrubbing, systematizing, and sustaining activities to

eliminate non-value-added elements (Valencia,

2006). Lean is recognized for its effectiveness in both

manufacturing and service industries. Six Sigma

Methodology, introduced by Motorola's Bill Smith in

1986, aims to eliminate errors and defects in business

processes (Antony, 2004). The DMAIC phases

(Define, Measure, Analyse, Improve, Control) focus

on measuring and analysing operational processes,

identifying root causes of defects, and implementing

improvements. Combining with Lean Manufacturing

results in Lean Six Sigma, enhancing savings and

efficiency across sectors. The Kaizen method,

implemented in Japanese industries after World War

II, emphasizes continuous improvement through

small, incremental changes involving all employees

(Radnor, 2010). Utilizing the PDCA cycle, Kaizen

fosters a culture of improvement at minimal

implementation costs. TQM is a system that aims to

increase customer satisfaction through continuous

improvement (Dahlgaard and Dahlgaard-Park, 2006).

It fosters a collaborative culture with active employee

participation, focusing on quality, long-term success,

and customer satisfaction. The methodology involves

process selection, preparation, analysis, redesign,

implementation, and improvement, leading to

financial, operational, and customer success.

Regardless of their benefits and challenges, many

of these methodologies are focused on the industrial

and manufacturing sectors. Furthermore, some are

not recommended for large companies, such as Super

Methodology, and others are too generic or complex,

making adopting difficult. Despite these

characteristics, these methodologies can be

references to more prescriptive approaches. Thus,

considering these methodologies, the Boomerang

Methodology proposed in this study is firmly based

on the PDCA – concerning a process that includes

planning, prototyping, evaluation, and continuous

improvements – combined with the Design Thinking

process concerning the people's collaboration and

creativity.

3 COLLABORATION AND

CREATIVITY IN BPI

Several approaches, especially those based on design

thinking (DT), can be used in BPI, focusing on

collaboration and creativity.

The Double Diamond Methodology involves four

stages — Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver.

Emphasizing collaboration encourages diverse teams

to ideate and refine solutions collaboratively,

Business Process Improvements in Hierarchical Organizations: A Case Study Focusing on Collaboration and Creativity

723

ensuring creative input at every stage of BPI

(Caulliraux et al., 2020).

The IDEO's Human-Centered Design (HCD)

framework focuses on understanding user needs and

involves continuous collaboration (Rosinsky et al.,

2022). Teams work together to empathize with users,

define problem areas, ideate creative solutions, and

implement iterative prototypes, fostering a

collaborative and user-centric BPI process. IBM's

Design Thinking approach integrates design thinking

into problem-solving (Liedtka et al., 2013). It

emphasizes collaboration through multidisciplinary

teams, encourages user feedback, and employs

iterative prototyping. This fosters a creative, user-

centric mindset in BPI projects, ensuring the final

solutions address stakeholders' needs and

experiences. The Service Design Thinking approach

involves visualizing and improving the entire service

experience (Stickdorn et al., 2018). Collaboration is

inherent as cross-functional teams work together to

understand user journeys, identify pain points, and

co-create solutions. This methodology strongly

emphasizes creativity and collaboration to enhance

the overall service or business process. Finally,

Stanford D.School's Design Thinking methodology

provides tools and methods for design thinking,

emphasizing collaboration and creativity (D.School,

2017). It includes brainstorming and prototyping,

fostering a hands-on, collaborative approach to

problem-solving in BPI. The Boomerang

methodology adopted in this current study is based on

this methodology.

All these methodologies share common traits of

user-centricity, iterative processes, and cross-

functional collaboration. They prioritize empathy,

ensuring solutions resonate with user needs. Cross-

functional teams with diverse perspectives

collaborate in problem framing and creative ideation.

Visualization techniques, such as prototyping,

facilitate hands-on understanding and foster

creativity. Open communication encourages the free

exchange of ideas, creating a dynamic environment.

It is essential to highlight that, even with all these

positive characteristics, stakeholders' different power

levels can negatively impact open communication in

large, highly hierarchical organizations. In this

context, the proposal adopted in this study proved

entirely appropriate, as it combines the characteristics

of a DT-based process and gamification strategies to

guarantee everyone's participation, regardless of the

positions involved.

4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This qualitative research adopts action research and

the case study method. According to Patton (2002),

research is said to be qualitative when it aims to

investigate what people do, know, think, and feel

through data collection techniques such as

observation, interviews, questionnaires, document

analysis, interactive dynamics, and among others.

Merriam & Tisdell (2015) explain that action research

is an approach that aims to solve a problem in

practice, contributing to the research process itself

and addressing a specific problem in an authentic

environment such as an organization. Johansson

(2007) highlights that the case study must have a

"case" that is the object of study, which must be a

complex functional unit, be investigated in its natural

context with different methods, and be contemporary.

It is common for case studies to use several research

methods, considered a "meta-method," allowing data

collection from various sources and at different times,

which need to be cross analysed for consistent

considerations and conclusions.

The following subsections will present the

research steps and BPI methodology used in the case

study to clarify how the research was conducted.

4.1 Research Steps

The current study continues the applied research

published in (Picanço & Santos, 2022). The original

study's research problem was engaging, stimulating,

and motivating stakeholders in BPI projects. With

practical motivation, based on evidence found in the

authors' work environment, interviews with process

stakeholders, related studies in the literature,

exploratory research on creative companies, and an

investigation of collaboration and management

techniques, a methodology based on Design Thinking

(DT) and gamification strategy was defined, called

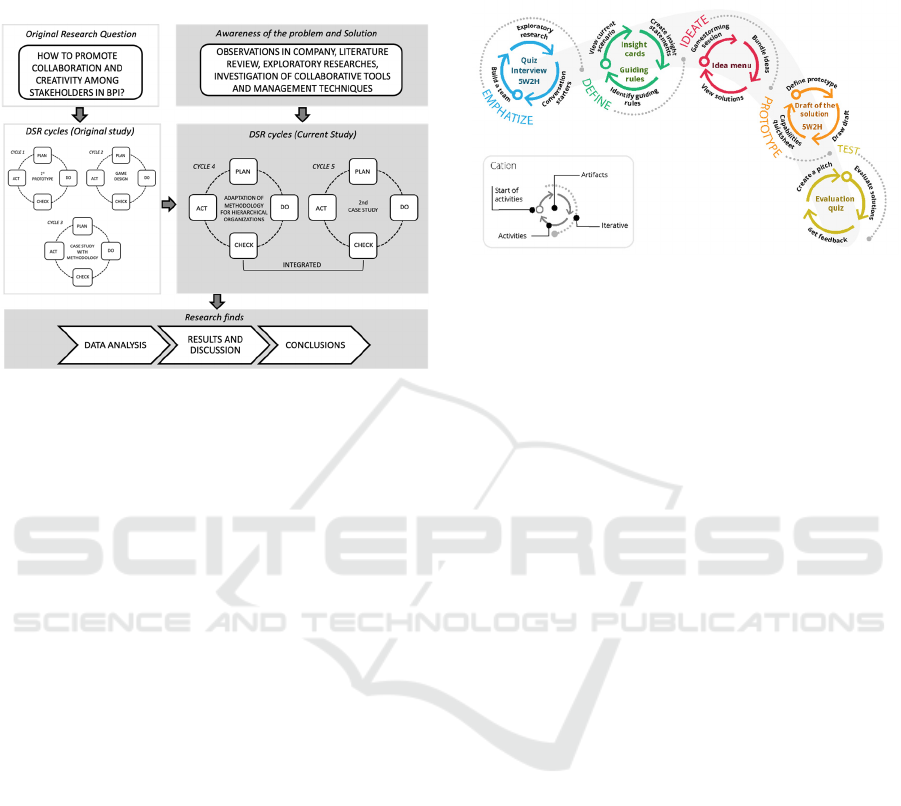

Boomerang Methodology. Figure 1 illustrates the

research process in summary.

The methodology was created following the

Design Science Research (DSR) method by Hevner

(2004) in three PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) cycles.

During the creation process, the methodology

evolved to define stages based on a DT process (cycle

1) and the need to build a collaborative game for the

ideation stage (cycle 2), which generally requires

greater participant creativity.

In (Picanço & Santos, 2022), considering

evaluating the usability and usefulness of the

methodology, a first case study was carried out on a

simple and short BPM project aimed at improving the

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

724

monitor selection process in a higher education

institution (cycle 3). The results were very positive,

in addition to identifying lessons learned and used as

recommendations for use (guides).

Figure 1: Methodology framework.

Continuing this research, the current study sought

to apply the Boomerang methodology in a complex

BPM project. Identifying the same problems as the

original research related to stakeholders' motivation,

engagement, and collaboration in business process

improvement projects, the methodology was quickly

identified as an appropriate strategy by the

consultants in this BPM project. Considering the

institution's characteristics (large, highly hierarchical,

and public sector) and the BPM project (legal sector

processes, strongly human-centered and knowledge-

intensive), some adaptations to the Boomerang

methodology were necessary (cycle 4), enabling its

use in this new scenario, detailed in the next section.

The new case study is detailed in Section 5 (cycle 5).

It is important to emphasize that both check steps of

DSR cycles 4 and 5 were carried out through

feedback from participants in the case study described

in this paper, discussed in Section 5.

4.2 Adapting BPI Methodology

The objective of the Boomerang Methodology is to

support the process analyst or any manager in a BPM

project in business process redesign activities

(Picanço & Santos, 2022). This support is based on a

DT process in five stages: empathize, define,

imagine, prototype, and test. Each stage involves

activities, guidelines for conducting these activities,

recommendations for artifacts and support tools for

each, and the definition of expected results. Figure 2

illustrates the Methodology process. The description

of these activities, guidelines, recommendations, and

expected results can be found in (Picanço & Santos,

2022).

Figure 2: Boomerang Methodology. Source: (Picanço &

Santos, 2022).

The Boomerang Methodology was developed to

motivate, engage, and stimulate business process

stakeholders' involvement, participation, and

creativity, focusing on BPI. To achieve this, the

Methodology is based on four principles: Innovation

& creativity, aiming to bring together people to

collaborate in solving problems in exchange for

recognition and offering new experiences to improve

processes; Engagement, seeking collaboration

mechanisms and promoting people's involvement and

motivation; Agility, understanding people's desires

and speeding up the production of ideas through

learning from errors and rapid evolution;

Adaptability, and can be applied and adapted to

different contexts and organizations.

Considering these principles, the Boomerang

Methodology was presented to a group of managers

and process analysts from a process office of a large

public institution in Law during the phase of

proposing improvements in a BPM project. This

group comprised six members: a process office

manager, a project manager, two process analysts,

and two BPM specialists. From this presentation and

discussions, it was decided to adopt the methodology

in a workshop format, as recommended in (Picanço &

Santos, 2022). Considering the institution's

characteristics, the need for some adaptations to the

Methodology was pointed out. The following

subsections describe the main changes at each stage.

4.2.1 Empathize

According to (Picanço & Santos, 2022), this phase is

concerned with ensuring empathy, recovering

people's stories, identifying the researched

community members, and beginning to understand

the problem to be solved. This stage has the following

Business Process Improvements in Hierarchical Organizations: A Case Study Focusing on Collaboration and Creativity

725

activities: team building, exploratory research, and

conversation initiation.

Considering the model of large hierarchical

institutions, forming teams involves selecting key

stakeholders involved with the process to be

redesigned and the need to maintain heterogeneous

teams concerning their roles and responsibilities.

These considerations reflect the need to form teams

that involve business areas (owners, users, and

process managers) and technology (systems and

infrastructure), in addition to participants with skills

in process modelling, such as the process analyst, and

with the power to conduct the workshop, as the

process office manager. It is essential to highlight

that, in complex processes, it is common for many

stakeholders to be involved in activities related to

various functional sectors. As a cross-functional

strategy, it is essential to identify which key

stakeholders should participate and define the number

of teams, enabling the effectiveness of the results and

control of the workshop.

Exploratory research activities often involve the

need for preparation on the part of workshop

participants so that they can contribute to proposing

improvements. Therefore, guests must receive a

communication explaining the project objectives, the

list of participants, and the expected results of the

event days before the meeting. Considering that large

projects involve their stakeholders from the initial

planning phase, it is natural that most guests already

know each other. However, a self-introduction by

each participant is recommended as part of the event's

opening. Finally, it is also important to establish good

conduct agreements for the workshop, such as

avoiding cell phone use, staying focused on your

team's work, and respecting time control.

4.2.2 Define

This step seeks a deep understanding of the needs,

constraints, and challenges to be faced through the

following activities: visualizing the current scenario,

creating an insights statement, and identifying

guiding rules.

In this study, this stage did not change; we only

reinforced some recommendations. The first of these

concerns the current scenario. Even considering that

the process improvement workshop is a step in the

BPM life cycle after other interactive steps of the

BPM project (such as planning, modelling of the

current process, and process analysis), it is crucial to

post the current process model (model As-Is) in the

environment where the in-person event will take

place so that stakeholders can consult it if necessary.

It is essential to note that this model should not be

entirely unknown to the participants, as it would

involve time spent explaining the process that would

compromise the improvement workshop's objectives.

Therefore, this model must be part of the information

necessary to prepare the meeting, provided for in the

previous stage of the methodology (Empathy).

Another critical point is to bring consolidated results

of earlier stages of the BPM cycle to the workshop,

such as initial ideas for solutions discussed in the

process analysis (insights) and guiding criteria such

as prerequisites, assumptions, and restrictions for

idealizing improvements.

4.2.3 Ideate

The Ideate stage aims to create new opportunities and

solutions for the challenge of process improvements,

containing the following activities: gamestorming

session, combining best solutions, and visualizing

solutions. The gamestorming activity is supported by

the game (Creative Thinking Planning game or CTP,

for short), developed in the second design cycle of the

methodology, allowing each participant to propose

ideas that are voted on by others, approving or

disapproving them. This was the main adaptation

made to the methodology.

In the initial version, the CTP game considered

forming a single team whose participants interact

with each other in proposing ideas and voting. So, the

first change was to adapt the game for multiple teams.

In the context of complex processes, a good practice

adopted by the market is to design the model as a

macro process composed of sub-processes. Thus,

multiple team formation favours identifying

improvements by sub-processes and provides an

integrated vision between the teams in understanding

the macro process. The second change was to adapt

the game's dynamics to enable short encounters of 3-

4 hours in length, considering multiple teams and

many ideas to manage. To achieve this, the number of

ideas to be defended by each team was limited, even

though several ideas were discussed among its

members. Finally, rejected ideas were discarded in

the initial version, while in this new version, rejected

ideas are recorded in a history of ideas, justifying the

results. The case study section will discuss this phase

and game dynamics.

4.2.4 Prototype

The Prototype stage results in implementing the ideas

generated in the previous stage through a new design

of the suggested process (To-Be model), in addition

to analysing the feasibility of the proposed solution

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

726

(Picanço & Santos, 2022). This stage has the

following activities: the definition of a prototype with

the selected ideas, the design of the improved process

draft, and the capabilities spreadsheet to support the

feasibility analysis.

Two main updates were made at this stage.

Considering the complexity of the process under

discussion and the work with multiple teams, the first

recommendation is that the process design can be

built by sub-processes led by their respective teams.

Planning time for integration between process models

during the workshop is essential, giving all

stakeholders a holistic view of the complete process.

The second update was the creation of a spreadsheet

to record ideas, with information on who, how, and

when to implement the solutions. This spreadsheet

also has specific tabs for analysing feasibility from

economic, technological, and chronological

perspectives, supporting the process analyst in

completing this stage. The case study will present

more details about this artifact in the next section.

4.2.5 Test

The Test phase supports feedback from those

involved more broadly, considering information

sharing among everyone. This stage has the following

activities: evaluate solutions, create a pitch, and

obtain feedback. The methodology maintained these

activities, including the time necessary for each team

to present the ideas incorporated in the draft To-Be

process and for debates about these ideas,

capabilities, and information about implementation

and feasibility. It is essential to highlight that all

participants voted on and approved all ideas

incorporated in the draft process designed in the

workshop.

After the workshop, a more detailed assessment

was carried out with all participants using an

electronic form consisting of seven questions (five

objective and two subjective). The objective

questions related to the information shared, group

work, activity quality, methodology, and workshop

conduction. These questions were segmented into

statement items, subject to evaluation based on the

Likert scale of five values: strongly disagree (SD),

partially disagree (PD), neither agree nor disagree

(NN), partially agree (PA), and strongly agree (SA).

Subjective questions refer to positive points and

points for improvement. More details about the

application of these assessments will also be

described in the case study section.

4.2.6 Comparing Boomerang with Others

BPI Methodologies

The Boomerang method is unique in its structured yet

flexible approach, incorporating elements like

gamification for engagement, a straightforward five-

stage process for innovation, and adaptability to

different organizational contexts. It aims to make the

process improvement experience more engaging and

innovative, contrasting with methodologies that may

focus more on efficiency, standardization, or

statistical control. Unlike Boomerang, MIPI is more

about harmonizing existing processes with standards

and less about innovation and engagement. The Super

Methodology, while also versatile, may not

specifically prioritize user experience and rapid

ideation as Boomerang does with its five stages.

Considering the Benchmarking Methodology,

Boomerang emphasizes internal innovation and

creative problem-solving rather than external

comparison. Boomerang shares a cyclic nature

(through its stages) as PDCA cycles but adds a strong

focus on creativity and user engagement. Unlike

Boomerang, Lean Thinking is more about

streamlining and efficiency than exploring innovative

solutions. Boomerang, while potentially benefiting

from Six Sigma's analytical rigor, places more

emphasis on ideation and adaptability. Kaizen and

Boomerang emphasize engagement, but Boomerang

specifically incorporates gamification and a

structured five-stage process. TQM shares a focus on

quality and involvement with Boomerang but may not

explicitly prioritize rapid prototyping and testing.

5 CASE STUDY

The case study was conducted in a Pernambuco Court

of Justice (Brazil) by its BPM Office (BPMO) with

the support of a consulting team from the Centre of

Informatics at UFPE University. The institution is

part of the public sector and has a low level of

maturity in BPM. There are a few documented

processes, some developed by the BPMO, but the IT

sector developed most.

In BPI workshop, the BPMO focused on the

Repetitive Demand Resolution Incident (RDRI)

process, considering its impact on the efficiency of

the judgments. The RDRI consists of generating and

setting a standardized judicial solution (legal thesis)

that can solve a mass of repetitive similar demands

that enter the institution (lawsuits filed in court). The

main intention was to optimize that process and allow

to monitor its performance. Between the start of the

Business Process Improvements in Hierarchical Organizations: A Case Study Focusing on Collaboration and Creativity

727

process and the generated decision application, a list

of procedures needs to be executed by different roles

and sectors. So, the process redesign was mapped

during the first phases of the pilot project with the

cooperation of diverse process stakeholders.

All stakeholders already knew the current state of

the process, and the BPMO needed their collaboration

to propose solutions for the problems and challenges.

At that moment, some concerns arose regarding the

engagement of stakeholders in this activity due to this

highly hierarchical environment.

The proposal to use the Boomerang Methodology

was grounded in the idea of active participation of

stakeholders from different sectors and mindsets.

There was a consensus that gamification would make

it possible to reduce certain inhibiting factors. Thus,

it was expected that all participants, not just the

magistrates, would feel confident in proposing and

approving – or rejecting – new ideas.

5.1 Applying BPI Approach

5.1.1 Empathize

The first stage was organically developed during the

BPM lifecycle's Design (As-Is modelling) and

Analysis phases. Since then, the involved team of

stakeholders has been collaborating with the

understanding of needs, problems to be solved, and

challenges in the process.

The first activity, “Build a Team,” was based on

the team of stakeholders of the project and other

collaborators with qualification or expertise related to

the theme and with different responsibilities. With the

help of the Strategic Management sector, the

workshop teams with seven facilitators (from BPMO

and consulting team) and 15 participants (project

stakeholders) were defined. From that moment of

defining participants, there had already been the

intention of composing heterogeneous groups. To

optimize the workshop execution, the participants

were divided into three heterogenous groups, each

with five members from different professional areas:

Process Operations, Process Management, Legal

(Magistrate), and IT.

The “Exploratory Research” was mainly the

compilation by the BPMO of the most relevant

information collected from interviews, meetings, and

questionnaires applied before the BPI workshop.

Many of the participants' teams had already

collaborated with the project precisely by providing

information about the process. Furthermore, the

entire defined group was familiar with the ongoing

project.

5.1.2 Define

According to the Boomerang Methodology, the first

activity of this second stage, "View Current

Scenario," consisted of presenting the current process

(As-Is) to the participants' team. Even though most of

them participated in the As-Is modelling workshop

the semester before, the visualization would be

crucial to rekindle everyone's memory and focus on

the workshop's goals. The BPMO team plotted the

As-Is model and posted it on one of the room's walls

to optimize the time available to hold the workshop

event, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: As-Is model plotted in the event.

The activities for creating an insight statement

were also previously developed by the BPMO based

on the information gathered until then. That way, the

Boomerang Methodology cards were set to start the

CTP game: 1) Challenge Cards were oriented by the

process indicators previously defined by the

institution's Strategic Plan, for example, the average

time to judge cases; 2) Insight Cards were based on

general ideas already given by some stakeholders in

the As-Is process analysis. Still, it was identifying

guiding rules related to the premises and restrictions

of the BPM project.

5.1.3 Ideate

The third Boomerang Methodology stage began with

the division of participants into three different

predetermined groups in different tables. A facilitator

with prior knowledge of BPM was assigned to assist

at each table. Four more facilitators were assigned to

perform the following activities: (1) introduce the

game dynamics and conduct the activities, (2) support

the voting process using a platform specialized in

game-based learning, and (3) assist all other

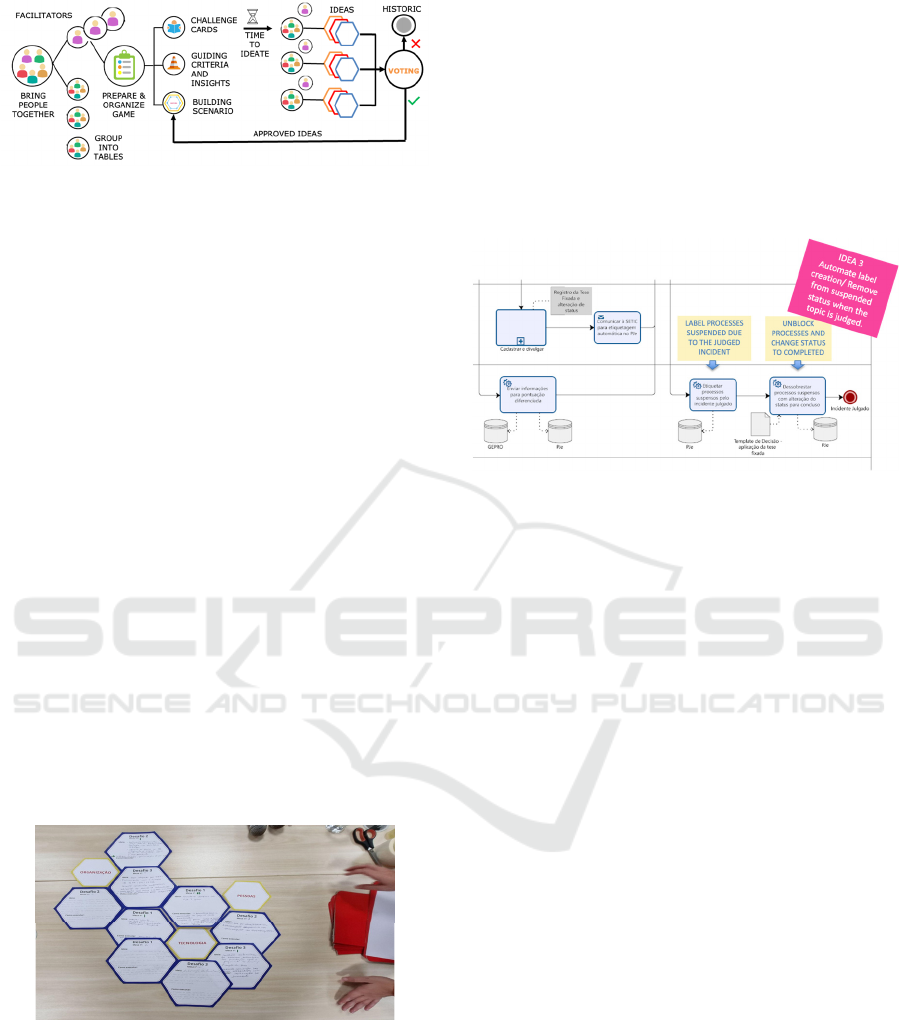

facilitators and participants. Figure 4 illustrates the

game dynamic.

After explaining the play mechanics, the

gamestorming began with the introduction of a

Challenge Card. The related guiding criteria and

Insight Cards were then presented.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

728

Figure 4: CTP Game dynamic. Source (Picanço & Santos,

2022).

Each group had the opportunity to (1) discuss

internally the problem presented, (2) think of possible

solutions, (3) choose one to three of them to register on

the blue anagram card (a hexagon-shaped paper card),

and finally (4) present and submit their idea(s) for

consideration and voting by the other participants.

Activities 1 to 3 took 20 minutes, and all group

members participated intensely. Activity 4, which took

2 minutes, was led by a group speaker aided by

colleagues' commentaries, and voting took 2 minutes.

A timer projected on one of the room's walls controlled

the duration of activities. From the tutor's perspective,

the motivation and engagement of participants in these

activities were evident, as will be shown in Section 5.2.

This cycle was performed three times, one for

each Challenge Card introduced. Of the nine

anagrams presented, only one was not approved by

the other groups. It is important to highlight that the

unapproved idea was from a magistrate participant

(top management), highlighting how democratic this

approach is. The approved ideas were placed near

their respective yellow anagram cards (Organization,

People, and Technology), forming a hive, and thus

showing their connections with each of the themes

represented on the cards, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Approved solutions posted in an anagram.

5.1.4 Prototype

At this stage, the groups registered the approved

solutions on the “Menu of Ideas.” Then, with the help

of BPM analysts (facilitators), the solutions

mentioned above were designed in BPMN.

The first activity was to define a prototype with

the approved ideas. To reduce redundancy among

similar submissions, it was agreed that only one of the

groups that suggested overlapping ideas would be

responsible for modelling them.

After that, the groups filled out the capabilities

spreadsheet to support the feasibility analysis of each

approved idea. The time spent for these two activities

was 1 1/2 hours, and by the end, except for only one

solution, all the others were prototyped in BPMN and

had their feasibility sheets filled. Figure 6 shows one

of these prototypes, after process update.

Figure 6: Process model considering idea 3.

5.1.5 Test

The last Boomerang Methodology stage is intended

to consolidate the ideas generated for the new process

during the event. Considering the limitation of time

to execute the workshop, the BMPO decided

previously that this stage activities would be mainly

realized asynchronously. Therefore, the first and

second activities, “Evaluate Solutions” and “Create a

Pitch,” were developed by the BPMO team as part of

the BPM Lifecycle To-Be stage. The “Evaluate

Solutions” activity was carried out from 3

perspectives of viability: technological, economic,

and chronological. Based on the information gathered

with stakeholders, each solution was rated from 1 to

10 in these three aspects. This information is relevant

to rank and select the solutions implemented at the

BPM Lifecycle Implantation stage.

5.2 Assessment & Analysis

The last Boomerang Methodology activity, “Obtain

Feedback,” was executed through an electronic form

sent to the workshop participants. To coordinate the

collected data, the research was carried out from the

following perspectives: information shared, group

work, activity quality, Boomerang methodology,

workshop conduction, the positive points, and, finally,

points for improvement. The first five questions were

objective ones. This evaluation is based on the assess-

ment model proposed in (Picanço & Santos, 2022),

considering the usability and utility of the approach.

Business Process Improvements in Hierarchical Organizations: A Case Study Focusing on Collaboration and Creativity

729

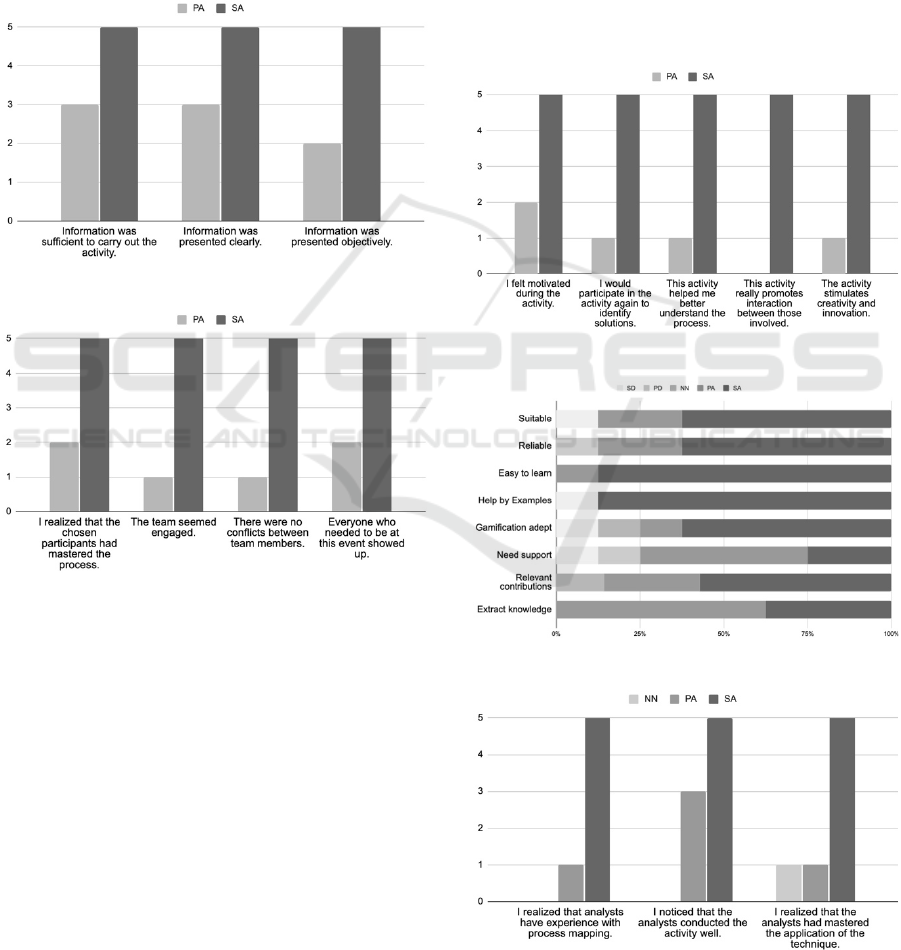

Regarding the information provided to realize the

activities, 100% of the interviewees agree (strongly

and partially) that it was enough and clearly and

objectively presented, as shown in Figure 7.

About the group of participants, 100% agree

(most strongly) that the selected participants had full

knowledge about the process and showed

engagement during the event, as shown in Figure 8.

There were no conflicts between the participants, and

88% (strongly agree) indicated that everyone who

needed to participate attended the workshop.

Figure 7: Information shared results.

Figure 8: Group work results.

Regarding their feelings about the overall

workshop (Figure 9), 100% of the interviewees agree

(most strongly) that they felt motivated during the

activities, stated that they would participate again to

identify solutions, that the seminar had contributed to

a better understanding of the process, and that the

activities can stimulate creativity and innovation, and

opined that the workshop dynamics promoted the

interactions between participants.

Regarding the technique adopted (Figure 10),

100% of the respondents agree that most people

would learn the methodology easily and that the

Boomerang was capable of extracting their

knowledge about the process; 88% reported that the

Boomerang is entirely adequate to improve business

processes, that they felt it trustworthy, that they felt

comfortable to apply the concepts and techniques into

real-life situations, and that the workshop offered

practical examples that helped the better

understanding of the gamification; and 75% opined

that the technical support is needed to utilize the

techniques and disagreed that the Boomerang does

not favour the contribution with essential insights.

About the process analysts that conducted the

workshop (Figure 11), 100% agree (strongly and

partially) that the analysts conducted well the

workshop dynamics and 88% had the perception that

the analysts had experience with process mapping and

had a domain of the Boomerang application.

Figure 9: Quality activity results.

Figure 10: Methodology results.

Figure 11: Workshop conduction results.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

730

The last two questions were subjective. The first

subjective question asked about the positive points of

the workshop. The respondents highlighted the clarity

and objectivity of the explanations, the interaction,

the engagement, the acquisition of knowledge, the

plurality of professionals involved, and the suitable

place to carry on the activities.

Finally, the second subjective question asked for

points for improvement. The interviewees pointed out

that there should be more time to debate since some

of the participants couldn't always contribute because

of that limitation; the voting system adopted could be

a better one; it would be better for the competition if

there were more clarity about the level of

development of the ideas; it would be better if the

event had more breaks because the overall duration of

the event.

5.3 Discussions: Lessons Learned and

Guidelines

Adopting the Boomerang Methodology in the BPM

project in a large, highly hierarchical organization

revealed opportunities and challenges. On the one

hand, it was easy to integrate the approach into the

BPI stage, benefiting from the outputs generated in

the previous stages of the BPM cycle. On the other

hand, we encounter difficulties due to common

factors when applying new dynamics with

heterogeneous groups in interests and levels of

power. As main lessons learned and guidelines, we

highlight the following:

Simplification of the initial steps: The Empathize

and Define steps could be executed quickly and

objectively since both the potential participants and

the information about the As-Is process were already

mapped. Thus, the Boomerang Methodology's initial

stage can be simplified when adopted in a large

project as part of a BPM cycle.

Number of challenges for the Ideate stage: An

aspect identified in the Define stage was related to the

number of possible obstacles to be proposed. Ten

specific problems had already been detected in the

As-Is process. Still, as there was not enough time to

apply the dynamics aimed at all of them, the BPMO

team needed to abstract the problems according to the

process phases, and, therefore, some possible

emphases could not be taken advantage of. This

situation indicated that an analysis of the BPMO is

necessary during the planning of the BPI workshop,

sizing the workshop based on the perspectives of

quantity and complexity of the challenges and time

control. Depending on the case, more than one

workshop may be necessary to meet the desired

objectives without compromising the involvement

and motivation of participants.

Coordination of the game: It is important to

highlight two other aspects of this phase. The first

relates to redundant ideas of possible solutions for

each challenge since the groups developed solution

ideas simultaneously and without knowing the other

teams' ideas. In the case of redundant ideas, consider

the score for all groups involved. The second aspect

concerns care with the voting system. The original

system proposed by the Boomerang Methodology is

based on coins and (tangible) paper. In the case study,

an electronic system was adopted, and some

participants who did not know how to use the voting

tool correctly voted for ideas that had not yet been

presented, causing the system to be restarted a few

times and causing a waste of time.

Process prototype: a lesson learned in the

Prototype stage was the application of BPM notation

to model the new process based on the approved

solutions. As months have passed since the As-Is

process modelling event, many participants have

forgotten the BPMN notation. At the end of the event,

when there was not much more time available, the

facilitators had to act as process modelers. Therefore,

it is essential to highlight the BPM notation to

participants and display the As-Is models placed on

the walls.

Assessment of approved ideas: As BPMO carried

out the Testing stage based on all the information

collected in the workshop, some doubts arose in the

validation meeting, especially when the solution

presented involved redundant ideas with slight

differences between them. Even so, this mishap was

resolved through debate and voting. In the end, there

was consensus on applying the approved solutions in

the new To-Be process.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In large, highly hierarchical organizations, it becomes

a significant challenge to objectively improve a

business process in a participatory and creative way.

The challenges are even more significant when these

processes are human-centred and knowledge-

intensive in a traditional organizational structure,

dependent on different interests and power levels. In

this scenario, BPI approaches based on Design

Thinking and engagement strategies, such as

gamification, can involve and motivate different

professionals and perspectives with a business

process and its needs, developing a cross-functional

vision of the BPM organization and culture. The case

Business Process Improvements in Hierarchical Organizations: A Case Study Focusing on Collaboration and Creativity

731

study and evaluations indicated that the main

objective was achieved. As a result, a new business

process was implemented in the organization, and the

Boomerang methodology was incorporated into the

BPMO methodology.

In future works, new BPM projects will be

initiated in this organization, considering the lessons

and recommendations learned in this study for BPI

stage.

REFERENCES

Adesola, S., & Baines, T. (2005). Developing and

evaluating a methodology for business process

improvement. BPM Journal, 11(1), 37-46.

Ahmad, T., & Van Looy, A. (2020). Business process

management and digital innovations: A systematic

literature review. Sustainability, 12(17), 6827.

Antony, J. (2004). Some pros and cons of Six Sigma: an

academic perspective. TQM Magazine, 16(4), 303-306.

Attaran, M. (2003). Information technology and business‐

process redesign. BPM journal, 9(4), 440-458.

Brocke, J. V., Rosemann, M. 2015. “Business Process

Management”.

Brown, T. 2009. “Change by design: how design thinking

transforms organizations and inspires innovation”. New

York: Harper Business.

Caulliraux, A. A., Bastos, D. P., Araujo, R., & Costa, S. R.

(2020). Organizational optimization through the double

diamond-Applying Interdisciplinarity. Brazilian

Journal of Operations & Production Management,

17(4), 1-12.

Cereja J.R., Santoro F.M., Gorbacheva E., Matzner M.

(2018). “Application of the Design Thinking Approach

to Process Redesign at an Insurance Company in

Brazil”. In: vom Brocke J., Mendling J. Management

for Professionals. Springer, Cham.

Dahlgaard, J. J. and Dahlgaard-Park, S. M. (2006) Lean

Production, Six Sigma Quality, TQM and Company

Culture, TQM Magazine, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp 263-281.

Dragolea, L, & Cotirlea, D. (2009). Benchmarking-a valid

strategy for the long term? Annales Universitatis

Apulensis Series Oeconomica, 11(2), 813-826.

Figl, K., & Weber, B. (2012). Individual creativity in

designing business processes. In CAiSE 2012, Gdańsk,

Poland, pp. 294-306. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Ghatari, A. R., Shamsi, Z., & Vedadi, A. (2014). Business

process reengineering in public sector: ranking the

implementation barriers. IJPMB, 4(3), 324-341.

Jeston J., Nelis J. (2006). Business Process Management:

Practical Guidelines to Successful Implementations.

Oxford: Elsevier Ltd.

Johansson, R. (2007). On case study methodology. Open

house international, 32(3), 48-54.

Kock, N. (Ed.). (2005). Business Process Improvement

through E-Collaboration: Knowledge Sharing through

the Use of Virtual Groups. IGI Global.

Lee, K. T., & Chuah, K. B. (2001). A SUPER Methodology

for Business Process Improvement-An industrial case

study in Hong Kong/China. IJOPM, 21(5/6), 687-706.

Liedtka, J., King, A., & Bennett, K. (2013). Solving

problems with design thinking: Ten stories of what

works. Columbia University Press.

Merriam, Sharan B. and Tisdell, Elizabeth J. (2015)

"Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and

Implementation". Jossey-Bass, Fourth Edition.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation

Methods. 3rd. ed. California: Sage Publications.

Pernici, B. and M. Weske, M. (2006). Business process

management, Data & Knowledge Engineering, vol.56,

no.2, pp.1-3.

Picanço, C. T., & dos Santos, S. C. (2022). Promoting

Collaboration and Creativity in Process Improvement:

A Proposal based on Design Thinking and

Gamification. In ICEIS (2) (pp. 418-429).

Pihir, I. (2019). Business process management and digital

transformation. Economic and Social Development:

Book of Proceedings, 353-360.

Radnor, Z. J. (2010). Review of business process

improvement methodologies in public services.

Advanced Institute of Management Research (AIM

Research).

Rashid, O. A., & Ahmad, M. N. (2013). Business process

improvement methodologies: an overview. Journal of

Information System Research Innovation, 5, 45-53.

Rosemann, M. (2015). “Proposals for future BPM research

directions”. 2nd Asia Pacific Business Process

Management Conference, Brisbane, p. 1-15.

Rosinsky, K., Murray, D. W., Nagle, K., Boyd, S., Shaw,

S., Supplee, L., & Putnam, M. (2022). A review of

human-centered design in human services. Human

Centered Design for Human Services.

Smith, H. (2003). Business process management—the third

wave: business process modelling language (bpml) and

its pi-calculus foundations. Information and Software

Technology, 45(15), 1065-1069.

Sokovic, M., Pavletic, D., & Pipan, K. K. (2010). Quality

improvement methodologies – PDCA cycle, RADAR

matrix, DMAIC and DFSS. JAMME, 43(1), 476-483.

Stickdorn, M., Hormess, M. E., Lawrence, A., & Schneider,

J. (2018). This is service design doing: applying service

design thinking in the real world. O'Reilly Media, Inc.

Stojanović, D., Slović, D., Tomašević, I., & Simeunović, B.

(2016). Model for selection of business process

improvement methodologies. In 19th International

Toulon-Verona Conference on Excellence in Services

(Vol. 5, pp. 453-467). Huelva.

Valencia S. (2006). Process Improvement: Which

Methodology is best for Your Project? Consulting

systems outsourcing, CSC.

Van Looy, A. (2018). On the synergies between business

process management and digital innovation. In: 16th

International Conference, BPM 2018, Sydney, NSW,

Australia, September 9–14, 2018, Proceedings 16 (pp.

359-375). Springer International Publishing.

ICEIS 2024 - 26th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

732