New Insights into the end-User Requirements for Remote Monitoring

for Aging at Home Contributions to the Third Digital Divide

Cosmina Paul

a

, Andreea Stamate

b

and Luiza Spiru

c

Ana Aslan International Foundation, Spatarului nr 3, Bucharest, Romania

Keywords: Older 47Adults, Gerontographics, Monitoring, Digital Divide, Data Ethics.

Abstract: Well-being and independence are highly valued in Western European countries. Though, we need a more in-

depth understanding of how older adults and their next of kin perceive how monitoring technologies can

support ageing at home. Older adults are the most heterogeneous population in terms of health and functional

status comparative to all the other age groups and their formal and informal caregivers need also to be

accounted for in this endeavor. Therefore, the understanding of the process of accepting and adopting new

monitoring products is cumbersome as the current low adoption rates show despite innovators promises. By

employing a gerontographics approach, we aim at understanding what are the older adults’ expectations from

remote monitoring, a growing industry but with a low adoption rate. Hence, we have concluded that a) all

categories are interested in alarm features rather than day to day monitoring, b) the more independent one is,

more interested is in controlling/ handling the device, c) those psychologically well are rather stressed about

monitoring and prefer not to trade their privacy for safety,) all next of kin are much interested in high data

accuracy. We have also noted that the first and second digital divides, related to costs and relevance, persist,

and they add up to the third one. The third digital divide is about to happen, with respect to data and ethics of

the technologies, the need of the older adults or their next of kin to control and understand the device.

1

INTRODUCTION

At the outburst of the Covid-19 pandemic, people

reacted emotionally by singing songs out of their

balconies – a strong emotional response to an

essentially medical issue. However, in time, due to

lockdown measures, these emotional responses faded

away and people adjusted to technology-mediated

communication. Placing our focus on the alleged

impact of technology on emotions, the overall aim of

our project is to contribute to the understanding of

how technology affects the way we care. What are the

challenges brought by new technologies – such as

diminishing human contact – to the way we are and

feel being cared for, and our capacity to care for

others?

On the same par, the world population is ageing

(Eurostat, Ageing Europe, 2020). Worldwide, there is

a sharp increasing in the need for care and the Covid-

19 pandemic exacerbated this need (Power, 2020;

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3827-2290

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3385-9714

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5308-205X

Alharbi et al, 2020). It is not only that there are just

fewer family caregivers available to provide everyday

assistance, but many of them are experiencing their

own physical and mental health challenges, at a rate

that can be as high as 70-80% (Alex Mihailidis,

ICT4AWE, 24-26 April, 2021).

As the wide range of implications of increasing

numbers of the older population is becoming a public

agenda, the need for technology adoption, as a

solution to face this problem, increases as well.

Literature shows that remote monitoring

technology, coupled with care-coordination, has the

potential to revolutionize the way older adults are

“Aging in Place”. This belief led to a context where:

a) Remote patient-monitoring industry is growing

and there is still high demand and b) All these

technological solutions are designed to complement

the increasing need for care which is answered

through: at-home caregivers, nursing homes, or PERS

devices (PERS personal emergency response

Paul, C., Stamate, A. and Spiru, L.

New Insights into the end-User Requirements for Remote Monitoring for Aging at Home Contributions to the Third Digital Divide.

DOI: 10.5220/0012730400003699

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2024), pages 291-297

ISBN: 978-989-758-700-9; ISSN: 2184-4984

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

291

system).

The success of remote monitoring technology is

allegedly given by the degree of being perceived as

unobtrusive and/or non-stigmatizing. Hence,

independent older adults would prefer devices which

are not wearable but passive – (More passive, more

successful, Vedantam, 2021) and, more, able to

detect a range of emergencies, and require no or

minimal action on the part of the user (Rantz et al,

2013; de Bruin et al, 2008).

On the same part, the perception of the product by

the caregivers is equally relevant. They need to

clearly understand the degree to which the assistive

technologies give them peace of mind and ease their

burden. Hence, older adults’ monitoring is meant to

support reducing caregiver burden and preserving

well-being outcomes for older adults (Czarnuch and

Mihailidis, 2011; Marasinghe, 2016; Creber et al.,

2016).

With respect to the professional care providers,

beyond their effectiveness, performance also

increases as more time is allocated to implementing

interventions. Along these advantages there are also

some limitations of remote monitoring, which refer to

a) high costs, b) the impossibility to assess the

performance of an individual, and c) accuracy is

limited because the collected data is rather inferred.

If we closely look to the evolution of remote

monitoring, we see that it encompasses the

advantages and limitations of the first and second

grey digital divides, which have been already

discussed at large within the research milieu

(Karahasanovic´ et al, 2009; Delello et al, 2017;

Battersby et al, 2017). The first refers to the low

adoption of the technology by the elderly because of

high costs, while the second divide refers to the

suboptimal adoption of technology by the elderly

because of new products’ lack of relevance to them.

van Deursen et al (2015) are discussing the upcoming

of the third divide of technology adoption which

relates to a lack of theoretical development about

which types of people are most likely to benefit from

technological innovation.

In our view, the first and second digital divides

gave not been overcome but, more they contribute to

deepen the third one. The answer for understanding

the correct status of the digital divides relies in the

right older adult population segmentation and co-

creation process, specifically involving older adults to

contribute from the concept development phase,

rather than only in the stages of testing solution as

end-users.

2

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

2.1 “Theoretical Framework”

We employ a gerontographics segmentation, which

suggests that rather than considering age per se, more

accurate and relevant data are to be obtained when

accounting for physical and psychological state of the

older adults. Geronthographics is an approach

developed by Moschis (1996) and it shows its

efficacy in analysing elderly’ consumer activity based

on their physically and psychologically state

(Nimrod, 2013; Sthienrapapayut et al, 2018).

Therefore, Moschis refers to four categories of older

adults which are selected based on their state of health

on a continuum from independency towards

dependency (Moschis and Mathur 1993; Moschis

1996, 2003;). The approach assumes that older adults

show similar behaviour consumer activity if they had

encountered similar circumstances, experiences and

past events, based on the type of aging experience.

Starting from the gerontographics segmentation,

we have found that in the case of older adults

psychologically well, the ‘Perceived Usefulness’ of a

new technology determines the acceptance or rejection

of a technology, while in the case of those psycholo-

gically unwell, the influence of the formal and/or

informal caregivers is decisive (Paul and Spiru, 2021).

For example, if a person is overall physically and

psychologically well, then the A4A Solution needs to

detect the transition towards either physically well

and psychologically unwell or physically unwell and

psychologically well.

MoSCoW Prioritization for Older adults

psychologically well. Must have: Limited usage: just

for a notification or alarm, The option to control the

device; Easy to install; Reliable alarm.

MoSCoW Prioritization for Older adults

psychologically NOT well: Pre-alarms; Basic ADL

identification, toileting or feeding; (Individualized)

Movement behaviour patterns.

Tak et al (2013) presents a meta-analysis of the

association between physical activity (PA) and the

incidence and progression of basic ADL disability

(BADL) positioning PA as the most effective

preventive strategy in preventing and reducing

disability, independence and health care cost in aging

societies. More, functional independence influences

emotional wellbeing, while emotional well-being

predicts subsequent functional independence and

survival. For example, Ostir et al (2015) support the

concept that positive affect, or emotional well-being,

is different from the absence of depression or

negative affect. Their study results show that positive

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

292

affect seems to protect individuals against physical

declines in old age. Katt et al (2009) shows that ability

to perform ADLs has little to do with cognitive well-

being, but is an influential factor in determining

emotional well-being.

Hence, to support aging at place and prolong

the independence of the elderly, we need to consider

both physical activity and emotional wellbeing for

functional independence.

But geriatric wellbeing, positive ageing, wellness

for the elderly or successful aging are, generally,

concepts assessed through both objective and

subjective indicators. Therefore, we define wellbeing

as the capacity of an older adults to at least

maintain/preserve their ADLs to the specific

gerontographics category to which they belong.

Hence, the transition to a different category is

prevented, slowed down or even reversed due to the

dyad of OA/NoKs and OA/PCP supported by A4A

remote monitoring system.

2.2 Methodology

Within the framework of the project “From Smart

Home to Care Home – AAL4All (A4A)”, co-funded

by the European Programme AAL (Active Assisted

Living – ICT), we have set up and undertook the

documentation and co-creation process from its very

inception and carried it out over the course of 2022.

We have taken a questionnaire-based survey

method, which is part of the Positivism research

approach, along with the explanatory design. The data

was collected through a semi-structured survey

questionnaire. The survey questionnaire was

circulated to respondents electronically through

internet and traditional hard copies. For electronic

distribution, Google Forms have been used and no

personal data have been collected.

However, each participant has been properly

informed on the purpose of the research and given the

possibility to withdrawn at any time. The data was

analysed using SPSS.

The survey was conducted by the end-user

organizations involved in the A4A project, in

Romania, Switzerland, Portugal and Denmark. The

survey was carried via online and face2face interviews

during the period of May to July 7, 2022, from a sample

of 202 adults. 107 participants are from Romania, 32

from Portugal, 27 from Switzerland, and 36 from

Denmark. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to 99

years (mean = 57.88 years, sd = 18.61 years), with

more than half (66.3%) female. Slightly more than one-

third of respondents (37.6%) reported living alone,

while nearly one third live with their spouse (27.7%).

Of those sampled, the adoption of the technology

which supports independence at home and quality of

living is low. 76% did not adopt any technology and

from those who did, smartphones and computers are

the most common adopted technologies.

The 7-Questions. Respondents were asked seven

questions relating to the relevance of various A4A

Solution features, in their quality as a care giver or a

care-receiver. The participants were asked to rate the

relevance of 7 features of the A4A Solution, on a

scale from 1 to 5. The mode (the most frequent value)

is 5 for each item (the participants rated the relevance

of each of the 7 features on a scale from 1 to 5).

The 7-question item which was asked is the

following:

How useful is the A4A device, for you or for

somebody you care for (e.g. your parents)? To send

a notification to a relative or carer if you (or your

care-receiver) did not get out of bed by a specific time

in the morning,

To know the Activities of daily living based on the

sound monitoring (eating, toileting, etc.), Proactively

generate an ALARM to the sounds” HELP" or

repetitive beats which might mean “HELP” to a next-

of-kin or professional carer, Identify the abnormal

movement behaviour (for example, overnight or high

toilet frequency, To switch off and on the device as

you (or your care-receiver) want, Early identification

of depression or anxiety, Early identification of

cognitive decline.

Participants

From the perspective of gerontographics

segmentation the population of people aged 65 and

over can be grouped in 4 categories, based on the

wellness or unwellness of their physical and

psychological status. Therefore, there are 4

categories:

1. Physically and Psychologically Well (Healthy

Indulgers)

2. Physically Unwell and Psychologically Well

(Ailing Outgoers)

3. Physically Well and Psychologically Unwell

(Healthy Hermits)

4. Physically and Psychologically Unwell (Frail

Recluses)

Individuals may move to the next life-stage due to

biophysical and psychosocial ageing process

(Moschis, 2019). That means that generally, someone

who is physically and psychologically well, through

the ageing process, in time, will become either

New Insights into the end-User Requirements for Remote Monitoring for Aging at Home Contributions to the Third Digital Divide

293

physically or psychologically unwell or both.

90 participants fell into the first category, (who

identify or self-identify as A4A beneficiary) being

physically and psychologically well. The group of

those who are physically and psychologically well is

over-represented comparative to the other groups.

44% live alone.

The second category comprises 30 participants,

who identify or self-identify as being physically

unwell and psychologically well. 70% are female.

The third category comprises 25 participants, who

identify or self-identify as being physically well and

psychologically unwell. 64% are female.

The fourth category comprises 23 participants,

who identify or self-identify as being physically and

psychologically unwell. 71% are female.

3

RESULTS

In line with other research findings, data show that

the first two hurdles of the digital divides have not

been fully past.

First Digital Divide: Costs

There is a sharp difference between those psychologi-

cally well and those psychologically unwell in the

decision of buying a monitoring product and assistive

technology in general. Those who are psychologically

well tend to adopt devices which are not specifically

designed for older adults and would tend to avoid

monitoring. Interestingly to note, when those

psychologically well are involved in testing or are

curious about the products, they would tend to feel

stressed about being monitored and to refuse

technology.

Whereas those psychological unwell would firstly

be influenced by others in this decision and tend to

accept any kind of monitoring or technology which

might support/ accompany/ or give a sense of being

secure.

For those psychologically well regardless of their

physical status, in the decision of NOT buying the

A4A Solution, the ‘technology alternatives on the

market’ is the less important factor, while all others

(price, privacy, not being monitored and false alarms)

are very relevant and relevant for about 60% of the

participants.

For those physically well and psychologically

unwell, the price matters the most in the decision for

not buying the product (60% rated 5 this reason in not

buying the A4A). Similar for the category of those

both physically and psychologically unwell, price is

the most important factor for not buying the product

(71%), followed by privacy (57,2%). Reticence for

being monitored is the least important factor in the

decision of not buying the product. A negative weak

correlation exists between the willingness to pay

more for the A4A Solution as long as they pay

themselves the price (Pearson correlation -.418).

Second Digital Divide: Relevance

The A4A Index

‘The A4A Index’ was conceived to assess the

robustness of the new technology proposed for the

seniors and their next of kin. The index puts together

7 key-measures of the new technology: ‘alarm’,

‘notification’, ‘anormal behaviour, ‘control

ON/OFF’, ‘ADLs’ cognitive decline’ and ‘mental

unwellness’.

A reliability test has been conducted, which

measures the internal consistency of the index, that is,

how closely related the set of 7 items are as a group.

The reliability test is conducted through Cronbach’s

Alpha, which is .917. That shows a high reliability

(significantly higher than .800).

On a scale from 1 to 5, the mean of the A4A Index

is 3.76 and the median is 4 and the mode, the most

common value, is 5 (19.5% rated with 5 each of the

A4A features). High relevance of the A4A Solution

was found among 48% (Those who rated 4 or 5 each

feature of A4A) and No relevance of the A4A

Solution was found among 20.7% (Those who rated

1 or 2 each feature of A4A).

The A4A Solution is seen as being very relevant

and relevant by the large majority of the participants.

The Alarm feature (‘Proactively generate an

ALARM to the sounds” HELP" or repetitive beats

which might mean “HELP” to a next-of-kin or

professional carer) is seen as being the most relevant.

The following 3 advantages: easy to install,

relevance of the alarm, and the price, are moderately

correlated to the relevance of the Index A4A (Pearson

Correlation .469; .468 and .405 respectively).

The advantage of ‘notifications of cognitive

decline’ is significantly stronger correlated to the

Index A4A (Pearson Correlation .679).

The Q4 Index “Worries” has a high reliability, and

weakly predicts the relevance of the A4A Solution

(Adjusted R Square= .208).

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

294

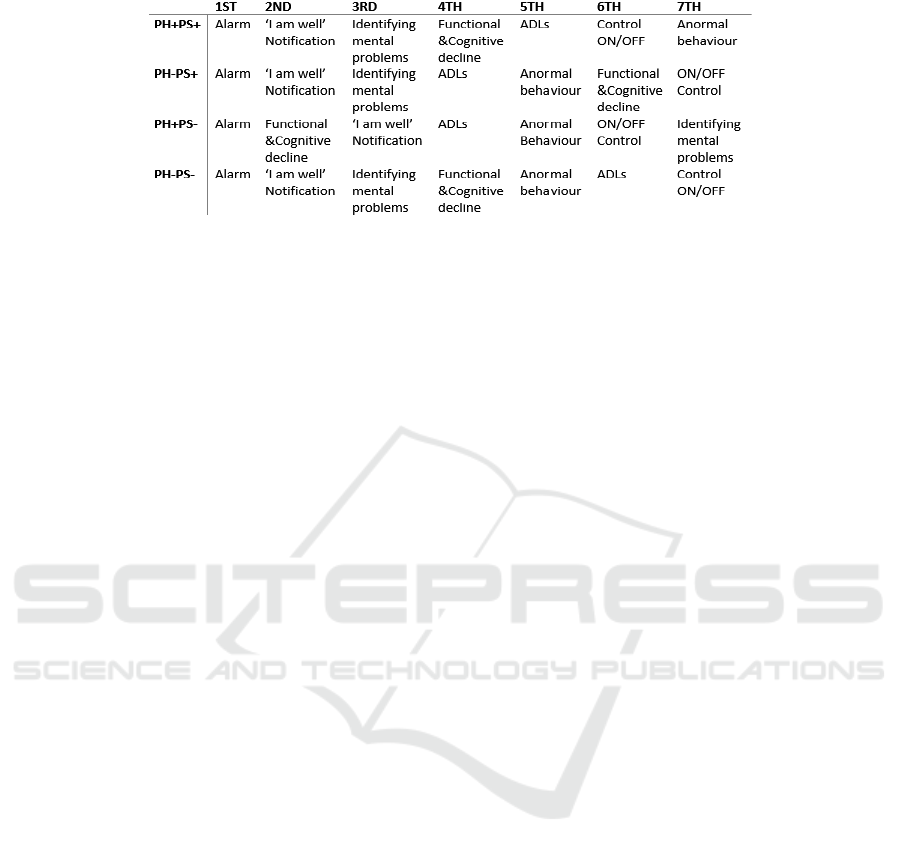

Table 1: The relevance of the A4A features.

The Q8 Index ‘the advantages which influence the

decision to buy the A4A Solution’ and The Q9 Index

‘the features which influence the decision NOT to

buy the A4A Solution’ are not reliable, meaning that

we cannot conclude on each advantage/feature of the

A4A Solution as counting in the decision to buy or

not to buy the product.

Therefore, we have decided to group the

participants in 4 groups, according to the

gerontographics segmentation in order to account for

more subtle preferences and characteristics of the

participants in relation to the A4A Solution. Hence,

the co-creation process was key in giving the right

direction towards the development of the new

technology

.

In line with literature review, the results show that

there is a wide range of requirements because older

adults (henceforth, OA) are a very heterogeneous

population, with many people over the age of 80

continuing to live independently, while others show

frailness and advanced cognitive impairment. The fact

that their next of kin (henceforth, NOK) and formal

care providers (henceforth PCP) are involved in the

A4A co-creation process as end-users and buyers

make the process more complex.

Those who exhibit psychological wellbeing and

have relatively good health conditions, regardless

of their age-related physical limitations and still

living independently would tend to adopt technology

which support their positive ageing. They look for

volunteering and community involvement as well as

new communication channels, and opt for

smartphone for tracking their physical activity (Paul

and Spiru, 2021). The healthy and independent older

adults and their professional and next of kin carers

think about A4A device as having some basic

functions:

-the control over the device and over the alarm,

-notification or pre-alarm to be sent to NoK or PCP if

they do not wake up,

-avoiding false alarms and easy to install.

They merely show that they want to keep their

independence and control over their life, while NoK

and PCP look to avoid overloading.

Those who Exhibit a Low Psychological Well-

Being. would tend to adopt technology who make

them feel more secure, have a feeling of being

supported and cared for. Hence, they would tend to

adopt remote sensors or wearables.

The Third Digital Divide: Ethics and More

As Ethics and data protection is a growing point of

concern for older adults. As people age and become

more and more accustomed to the new technologies

they are also more informed about the data protection

and ethics. Their next of kin claim more and more

transparency and information regarding data

collection and processing. Hence, they tend to refuse

monitoring until they reach the point of trading their

privacy for security.

Though, ethics and data protection is not the only

point of their concern. New monitoring products

require an ecosystem to be in place for them to

optimal function. Data interpretation is one point of

concern as current monitoring products add to the

burden of caring by asking their next of kin or

professionals to step in.

4

DISCUSSION

Research shows that there is a correlation between

physical activity and subjective well-being on the one

hand, and health and longevity on the other hand,

even there is still much more to learn about the

relation between the two. Growing evidence from

neuroscience, biology and social studies shows that

there is a strong connection between physical activity,

emotional wellbeing and functional independence but

more research is needed to establish the causation

direction and moderators.

New Insights into the end-User Requirements for Remote Monitoring for Aging at Home Contributions to the Third Digital Divide

295

With respect to monitoring technologies, the first

and second digital divides have not been yet

overcome. That is because one needs a whole system

in place for monitoring, such as the caregiver, the

system to run, data interpretation. All these further

restrict even the HAVEs to access monitoring

technologies because the ecosystems which allow

monitoring products to work are not in place. More,

even when they are, it is cheaper to opt for monitoring

only for accidents, i.e. fall alarms.

A4A Solution would infer on the ADLs and

IADLs to detect early anomalies in functional

independence. These early detected anomalies are

much related either to the deterioration of physical

activity, emotional or cognitive wellbeing.

5

CONCLUSIONS

We see that the first digital divide has not passed and

the costs of the assistive technologies and their

services stay high and widen the gap between the

have and have nots. With respect to the second digital

divide, we have also noted that the heterogeneity of

the older adult population leads to different

expectations based on the health and functional

status. A third digital divide is about to happen, with

respect to data and ethics of the technologies, the need

to control the device clearly expressed by the

participants.

To some extent, technology drives away emotions

in a process aimed at optimizing care. A nurse ceases

to hold someone’s hand because of the pulsometer,

children and older adults are monitored, surveillance

technologies are on the rise, doctors may gradually

become redundant due to AI of decision support

systems, and biometrics can tell you about subtle

changes in your body even before you can perceive

them (Harrari, 2018).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was performed in the frame of the national

project „Increasing research capacity and national

and international visibility of the Ana Aslan

International Foundation (FAAI), through promoting

research results”, SMART-BEAR, PN-III-P3-3.6-

H2020-2020-0174, nr. 61/2021 and EU project

AAL4All (AAL-2021-8-164-CP) funded by the AAL

Programme and co-funded by the European

Commission and the National Funding Authorities of

the partner countries.

REFERENCES

Battersby, L., Fang, M.L., Canham, S.L., Sixsmith, J.,

Moreno, S. and Sixsmith, A., 2017, July. Co-creation

methods: informing technology solutions for older

adults. In International Conference on Human Aspects

of IT for the Aged Population (pp. 77-89). Springer,

Cham.

Creber RM, Maurer MS, Reading M, Hiraldo G, Hickey

KT, Iribarren S. Review and analysis of existing mobile

phone apps to support heart failure symptom

monitoring and self-care management using the Mobile

Application Rating Scale (MARS). JMIR mHealth and

uHealth. 2016 Jun 14;4(2):e5882.

Czarnuch, S. and Mihailidis, A., 2011. The design of

intelligent in-home assistive technologies: Assessing

the needs of older adults with dementia and their

caregivers. Gerontechnology, 10(3), pp.169- 182.

De Bruin, E.D., Hartmann, A., Uebelhart, D., Murer, K. and

Zijlstra, W., 2008. Wearable systems for monitoring

mobility-related activities in older people: a systematic

review. Clinical rehabilitation, 22(10-11), pp.878-895.

Delello, J.A. and McWhorter, R.R., 2017. Reducing the

digital divide: Connecting older adults to iPad

technology. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(1),

pp.3- 28.

Grzes M, Hoey J, Khan S, Mihailidis A, Czarnuch S,

Jackson D, Monk A. Relational approach to knowledge

engineering for pomdp-based assistance systems with

encoding of a psychological model. KEPS 2011. 2011

Jun 12:77.

Istrate, D., Vacher, M. and Serignat, J.F., 2008. Embedded

implementation of distress situation identification

through sound analysis. The Journal on Information

Technology in Healthcare, 6(3), pp.204-211.

Karahasanović, A., Brandtzæg, P.B., Heim, J., Lüders, M.,

Vermeir, L., Pierson, J., Lievens, B., Vanattenhoven, J.

and Jans, G., 2009. Co-creation and user-generated

content–elderly people’s user requirements. Computers

in Human Behavior, 25(3), pp.655-678.

Katt JA, Speranza L, Shore W, Saenz KH, Witta EL. Doing

Well: A sem analysis of the relationships between

various activities of daily living and geriatric well-

being. The Journal of genetic psychology. 2009 Sep

30;170(3):213-26.

Madara Marasinghe K. Assistive technologies in reducing

caregiver burden among informal caregivers of older

adults: a systematic review. Disability and

Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. 2016 Jul

3;11(5):353-60.

Moschis, G.P., 1996. Gerontographics: Life-stage

segmentation for marketing strategy development.

Greenwood Publishing Group. Moschis, G.P., 2003.

Marketing to older adults: an updated overview of

present knowledge and practice. Journal of Consumer

Marketing, 20(6), pp.516-525.

Moschis, G.P., Mathur, A. and Sthienrapapayut, T., 2020.

Gerontographics and consumer behavior in later life:

Insights from the life course paradigm. Journal of

Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 30(1), pp.18-33.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

296

Moschis, George P. 2019. Consumer Behavior over the Life

Course. Research Frontiers and New Directions,

Springer Nature.

Nimrod, G., 2013. Applying Gerontographics in the study

of older Internet users. Participations: Journal of

Audience & Reception Studies, 10(2), pp.46-64

Ostir GV, Berges IM, Ottenbacher KJ, Fisher SR, Barr E,

Hebel JR, Guralnik JM. Gait speed and dismobility in

older adults. Archives of physical medicine and

rehabilitation. 2015 Sep 1;96(9):1641-5.

Paul, C. and Spiru, L., 2021. From Age to Age: Key

Gerontographics Contributions to Technology

Adoption by Older Adults.

Rantz MJ, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Flesner M, Hicks L,

Mehr D, Russell T, Minner D. The influence of teams

to

Spiru, L., Marzan, M., Paul, C., Velciu, M. and Garleanu,

A., 2019. The Reversed Moscow Method. A General

Framework for Developing age-Friendly Technologies.

In Multi Conference on Computer Science and

Information Systems, MCCSIS 2019–Proceedings of

the International Conference on e-Health 2019 (pp. 75-

81). Lisbon: IADIS Press

Tak, H.J., Curlin, F.A. and Yoon, J.D., 2017. Association

of intrinsic motivating factors and markers of physician

well-being: a national physician survey. Journal of

general internal medicine, 32(7), pp.739-746.

van Deursen, A.J.A.M. and Helsper, E.J. (2015), "The

Third-Level Digital Divide: Who Benefits Most from

Being Online?", Communication and Information

Technologies Annual (Studies in Media and

Communications, Vol. 10), Emerald Group Publishing

Limited, Bingley, pp. 29- 52

New Insights into the end-User Requirements for Remote Monitoring for Aging at Home Contributions to the Third Digital Divide

297