Review of Evaluations of Enterprise Architecture

Anders W. Tell

a

and Martin Henkel

b

Department of Computer and Systems Sciences, Stockholm University, Borgarfjordsgatan 12, Kista, Sweden

Keywords: Systematic Literature Review, Stakeholder Analysis, Enterprise Architecture, Evaluation, Work-Oriented

Approach, WOA, Relationship, Practice, Information Product.

Abstract: The use of information which is useful for collaborating stakeholders has encouraged and enabled businesses

to advance. Enterprise architecture (EA) provides frameworks and methods with information products that

aim to satisfy stakeholders' concerns. For positive effects to emerge from using EA, it is necessary, during

EA development and evaluation, to examine the work stakeholders do, their practices, how these practices

relate to each other, how EA deliverables contribute to stakeholders' work, and how EA information products

are (co)-used in stakeholders practices. This paper presents a systematic literature review on evaluations of

EA. The review aims to gain insights related to aspects of EA stakeholder practices and relationships that

were considered essential to evaluate and how different stakeholders contributed to evaluations of EA. The

insights are intended to inform the design of the Work-oriented Approach (WOA), which aims to enrich EA

stakeholder analysis and co-use of EA information products. The results of the survey show an uneven

contribution by stakeholders and that stakeholder practices and relationships were not clearly defined and

evaluated, leaving uncertainties about whether relevant stakeholders evaluated EA benefits. The lack of

stakeholder voices and details provides challenges to the validity of results relating to the organisational

benefits of using EA.

1 INTRODUCTION

Access to and exchanges of information that is

relevant, useful and valuable are essential for

organisations and stakeholders in their collaborations.

When people have to consider not only their own

actions but also other people's views and practices,

the design, production and consumption of useful

information become more complex.

Enterprise architecture (EA) is a field that works

with architectural knowledge and information

products (IP), such as models aimed to satisfy

stakeholders' concerns. Embedded in EA are

stakeholder analysis and management practices.

However, several challenges have been identified in

EA and its stakeholder analysis practices through

literature and empirical studies.

A case study of the use and utility of an

information product, the concept of capability, in EA

(Tell and Henkel, 2018) identified problems when a

single information product does not suit different

stakeholder-specific practices when the stakeholders

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3201-8742

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3290-2597

collaborate. For example, some stakeholders did not

see the utility of using the EA information product to

support their work. Literature studies of EA standards

and practised EA frameworks (Tell and Henkel, 2023)

(Tell, 2023) reveal that the representation of stake-

holders and their concerns is mostly not detailed, which

impairs understanding of who is doing what, together

with others, for what purpose, and impairs evaluations

of an IP's relative advantage (Dearing and Cox, 2018;

Venkatesh et al., 2003) compared to other IPs.

EA stakeholder analysis methods can also lack

support for representing relationships between

stakeholder practices, which limits analysis of

stakeholders' work in relation to each other and right-

sizing of the use of information products in a multi-

stakeholder environment (Tell and Henkel, 2023).

Furthermore, stakeholders can be reluctant to be

engaged in EA and participate in evaluations

(Kotusev, 2019), leading to misalignment between

stakeholders when not all stakeholder voices are

heard or when knowledge about stakeholders is

mediated by analysts (Tell and Henkel, 2023).

226

Tell, A. and Henkel, M.

Review of Evaluations of Enterprise Architecture.

DOI: 10.5220/0012734100003687

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering (ENASE 2024), pages 226-237

ISBN: 978-989-758-696-5; ISSN: 2184-4895

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Research has identified EA success factors

(Lange et al., 2016), but EA value-generating

mechanisms are often simplified (Ahlemann, Legner,

& Lux, 2021), and empirical evidence is based on

perceptions from not all stakeholders.

The above challenges led to the design of the

Work-Oriented Approach (WOA) that aims to

improve the representation, design, use, evolution and

evaluation of IPs such as EA models (Tell, 2023)

(Tell and Henkel, 2023). WOA offers an approach for

analysing, explaining and evaluating stakeholders'

(possibly diverging) interests and co-use of IPs based

on practices and relationships. WOA has the potential

to enrich the EA stakeholder analysis (Tell and

Henkel, 2023), increase stakeholder participation in

EA practices, and ultimately increase the relevance

and benefits of EA.

This paper aims to inform the design of the WOA,

which contains constructs and methods for

representing and evaluating the use of EA and other

information products in related practices, through a

Systematic Literature Review (SLR), exploring

aspects related to stakeholder practices and

relationships that were considered essential to include

in evaluations of EA and how different stakeholders

contributed to evaluations of EA.

The structure of the paper is as follows. The

analytical model used for the survey is described in

section 2, and the systematic literature review

methodology in 3. The research results in 4. Sections

5 and 6 conclude with discussions and a summary.

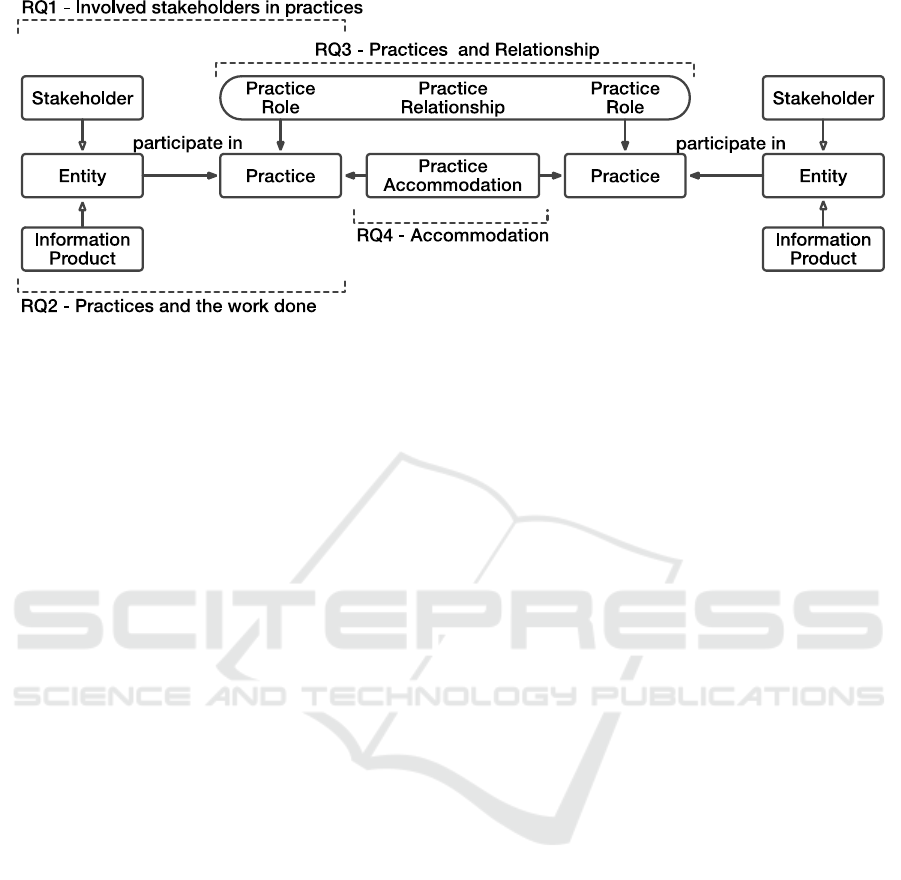

2 WOA AS ANALYSIS MODEL

In this paper, WOA (Tell, 2023; Tell and Henkel,

2023) is used as an analysis tool to examine how

evaluations of EA consider stakeholders, their

practices and relationships. While WOA contains

concepts and methods to describe practices and

relationships in detail, we only use the main concepts

here. Figure 1 portrays concepts in WOA relevant to

this paper.

In WOA, the work that stakeholders perform in

organisational settings is viewed as practices where

stakeholders participate, and information is needed,

offered and used. Stakeholders collaborate in

different formations and form relationships where

stakeholders produce, exchange, consume, and use

IPs, such as EA content, for mutual benefits.

WOA recognise that agents, such as stakeholders,

can have their own volition or purpose, points of

view, responsibilities, interests (Freeman, 2010), jobs

to be done (Ulwick, 2016), use of IPs, needs

(INCOSE, 2023), gains and pains (Osterwalder et al.,

2015), goals, and access to people and data. This

means they can also disagree, leading to potential

conflicts between collaborating agents.

The main concepts In WOA are described here:

Information Part: A separately identifiable body

of information that is produced, stored, and delivered

for human and machine use [Source: ISO 42010–-

Software, systems and enterprise–- Architecture

description, (ISO/IEC/IEEE, 2022)].

Information Product: An information part that is

intended to or participates in a practice. An EA model

is an example of an information product whose design

is governed by a model kind, such as a meta-model.

Agent: An entity that can bring about a change in

the world, such as a stakeholder or information

system.

Stakeholder: an agent (person or organisation)

that can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be

affected by a decision or activity (ISO/IEC, 2015).

Practice: The customary, habitual, or expected

procedure or way of doing something (Bueger and

Gadinger, 2014) (Nicolini, 2012) (Clark et al., 2018)

(Tell and Henkel, 2018).

Practices typically involve more than activities,

such as responsibilities, features, questions that can

be answered, access to data, information needs, and

pains that may be deemed relevant for a stakeholder’s

“what is in it for me” and the use of IPs.

Participation: Agents, such as stakeholders, and

Entities, such as information products, participate in

a practice in (thematic) roles. Participation of an

information product in a producer's practice is

different from participation in a consumer practice,

which means that the utility of an information product

in use can be different depending on the practice.

Furthermore, two practices may have different views

of a single information product that is intended to be

exchanged, resulting in two different but related

information products being identified and described.

For example, when a consumer has information needs

that are not matched by a proposed or produced

information product. Such diverging views of the

information product should preferably be resolved to

enable efficient collaboration.

Use: An entity such as an information product

participates in one practice where it is used.

Co-Use: An entity such as an information product

participates in more than one practice where it is used.

Practice Relationship: The way in which two or

more practices with their participating agents and

entities are connected, interact or involve each other.

Practice Role: How a practice plays a part or

assumes a function in a practice relationship.

Review of Evaluations of Enterprise Architecture

227

Figure 1: Illustration of main concepts of the WOA analysis model.

Practice Accommodation: How practices and

related entities fit or are suitable or congruous, in

agreement, or in harmony with each other. The

accommodation is a characterisation of a relationship

and of what entities in the practices (what)

structurally fit each other, the mechanism of how they

fit, and the effectuation of how the fit is (dynamically)

achieved through actions over time.

As an example, in the case of EA, the specific way

a produced EA model leads to reduced complexity,

where the fit is described as <EA model, (cause or

mean), reduced complexity (effect or end)>, the

mechanism is described as <description of

interconnected entities increase understanding of

complexities>, and the effectuation can be described

as <users are trained in understanding the EA model

before it is used>.

In WOA, practices, relationships, agents and

information products can be described at the desired

level of detail using a set of sentences from controlled

(domain-specific) languages (Group, 2019). Each

sentence can be associated with the agent that made

the sentence, which enables analysis of who said what

and whose voices are heard.

Alternative: Something which can be chosen

instead of something else.

WOA suggests that alternative (ISO/IEC/IEEE,

2019) practices, relationships and information

products should be considered during design and

evaluation to shift focus from local use of IPs to

organisational optimisation of co-uses of IPs and

aggregate utility of collaborations.

Relative Advantage: The degree to which using

something is perceived as better than something else.

To support design, innovation (Everett, 2003;

Dearing and Cox, 2018), and acceptance of the

information technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003),

WOA suggests considering and evaluating a practice,

a relationship, or an IP relative advantage compared

to other existing practices, relationships, or IPs.

Moreover, the WOA method enables the situating

and tailoring of generic IPs to stakeholders' specific

and actual work (Tell, 2023) to increase the value of

IPs by improving relevance, intention to use and by

providing a better fit between information needs and

information products in actual use.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This study relies on a systematic literature review

(SLR) approach where generated insights are

gathered and presented using an explicit and

reproducible method based on a four-phased process

proposed by Kitchenham (Kitchenham, 2007),

followed by the phase of writing the review. The 4+1

phases form a review protocol that is essential to

reduce the researcher’s bias, increase reliability and

improve the study's validity (Kitchenham, 2007).

3.1 Planning the Review

This review is motivated by the identified challenges

(Tell and Henkel, 2023; Tell and Henkel, 2018; Tell,

2018) and the intentions to improve WOA.

The SLR was preceded by an exploratory pilot

survey of articles with empirical grounded results

from evaluations of EA (Kitchenham, 2007). The

study indicated a diverse nature of evaluative EA

articles, which motivated a more systematic literature

review of articles to gain insights and suggest further

investigations. To structure the review, a set of review

questions was constructed to examine how the EA

evaluations addressed the issues of stakeholders, their

practices, relationships, and accommodations of IPs.

ENASE 2024 - 19th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

228

The review intends to answer the following primary

research questions:

RQ1: Which categories of stakeholders

contribute to EA evaluations of EA?

RQ2: How are practices and the work done in

practices part of the EA evaluations?

RQ3: How are relationships between practices

part of the EA evaluations?

RQ4: How are accommodations between

practices part of the EA evaluations?

The research questions aim to improve the

understanding of aspects that are considered essential

to include in evaluations of EA. RQ1 focuses on the

degree to which stakeholders' voices were heard

about aspects in their domains of interest, control and

responsibility. RQ2 focuses on the work stakeholders

do in their practices, and RQ3 on the relationships

between stakeholders' practices. RQ4 focuses on how

practices and related entities structurally fit and

causally relate with each other.

3.2 Data Selection

The principles for the data selection were established

before the review protocol was defined to reduce the

likelihood of bias (Kitchenham, 2007), and the search

terms, inclusion and exclusion criteria are based on

the research questions.

The search process aimed to identify primary

journals that reasonably can answer the research

questions (Kitchenham, 2007). The search and

indexing engines SCOPUS, Proquest, ACM Digital

library and IEEE Xplore were used, which include

articles from journals mentioned in the Senior

Scholars' List of Premier Journals as specified in 2023

(AIS, 2023).

The search terms were formulated liberally to

incorporate articles with poorly formulated abstracts

and keywords, but where the articles could be

relevant to the study (Kitchenham, 2007), and then

applied to the article's title, abstract and keywords.

The first set of search terms scoped the search for

articles in the field of enterprise architecture and the

publication period of the latest 10 years of articles

since 2013. The second set focused the results on

empirically grounded articles. Table 2 presents the

applied keywords, and Table 1 presents the inclusion

and exclusion criteria that guided the reviews of

individual articles to determine the relevance of the

articles to the research questions.

The quality of the search process and the

relevance and quality of articles were assessed using

the DARE criteria ((UK), 1995), where the review

satisfied the required 4 criteria.

Table 1: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Inclusion criteria

- Empirically grounded articles

- Peer-reviewed articles

- Journal articles, conference proceedings, books,

book chapters, and no conference reviews.

- Full-text articles

-En

g

lish lan

g

ua

g

e articles

Exclusion criteria

- Articles that report evaluations of methods,

constructs, and systems designed using EA and

not evaluations about EA itself.

- Articles in which the keywords exist but with a

different meaning from the study context.

- Duplicate articles.

- Articles that lack research methodology

- Conceptual, formative demonstrations, case

studies, explorative, or non-empirical articles.

- Theoretical and conceptual studies that are

based on informed reasoning and

demonstrations.

- Full articles that cannot be found.

3.3 Data Collection

The data and articles were extracted from each search

and indexing engine, added to the Bookends

reference database, where duplicates were removed,

and then added to the MaxQDA analysis tool,

supporting qualitative research methods.

3.4 Data Analysis

The articles were analysed using thematic analysis

(Myers, 2009) and the process outlined by Virginia

Braun & Victoria Clarke (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Coding notes: The articles varied greatly in focus,

detail and scope, leading to multiple revisions of the

codes and themes. The identified aspects related to

practices, practice relationships and practice

accommodations were drawn from evaluative

sentences and factors, which serve as indicators for

what the evaluators consider essential. For example,

many of the examined evaluations used Likert-scale

evaluative sentences when collecting data. These

sentences were used for analysis.

4 RESULTS

Following the review protocol, 29 articles were

collected for review, and 6 articles were snowballed

in, which saturated the insights. Table 2 presents the

Review of Evaluations of Enterprise Architecture

229

number of articles organised per search and indexing

engine after each step.

Table 2: Applied Search Terms and Reviewed Articles.

Search Criteria SCOPUS Pro

q

uest IEEE ACM

Conference Reviews, English language, June 2023, Search

Term "enter

p

rise architecture"

3338 2249 783 88

Search Terms: "evaluat*" or "verificat*" or "validat*" or

assess*

1022 388 247 23

Search Terms: "case study" or "qualitat*" or "empiric*" or

"quantitat*" or "survey*"

400 151 84 10

Only English, Peer reviewed, No Reviews, Commentaries

or Reports, Final papers, Full text

314 32 5 7

Restricted to Journals

98 32 5 1

Selected Primar

y

Articles 29

(Qazi et al., 2019; Kaddoumi and Watfa, 2022)

(Nikpay et al., 2017a) (Mirsalari and Ranjbarfard,

2020; Anthony Jnr et al., 2023) (M. and B., 2018)

(Ahlemann et al., 2021; Foorthuis et al., 2016)

(Jonnagaddala et al., 2020) (Nikpay et al., 2017b)

(Lange et al., 2016) (Alzoubi and Gill, 2020) (N. and J.,

2014) (Perez-Castillo et al., 2021)

(Bernaert et al., 2016;

Rouhani et al., 2019) (Abraham et al., 2015) (R. et al.,

2020) (Al-Kharusi et al., 2021) (Kotusev, 2019)

(Fakieh, 2020) (Niemi and Pekkola, 2016) (Doumi, 2019)

(Ahmad et al., 2020)

(Zhou et al., 2020) (Dang, 2021)

(Nakakawa et al., 2013) (Nor et al., 2021) (Rogier,

2021)

Snowballed Articles 6

(Shanks et al., 2018) (M. et al., 2015; Pattij et al.,

2020; Plessius et al., 2014; Aier, 2014; Alaeddini et

al., 2017)

4.1 Stakeholder Contribution (RQ1)

The stakeholders' contributions were coded by

individuals' participation in surveys and interviews

(respondents) grouped by categories of stakeholders,

as presented in Table 3.

The reporting varied in detail among the articles,

and it was difficult to categorise respondents due to a

lack of precise information. Detailed coding was

attempted but determined not to provide reliable and

valid results. In many cases, the organisational role

was not reported (column Unknown and row

Undetermined), and often general terms were used,

such as ‘manager’ and ‘architect’, which made it

difficult to understand which kind of individual's

voice was heard (rows Mixed).

The predominant data collection methods in the

articles were surveys and interviews where the

population was asked about their perception of

evaluative sentences. The contentious use of

perceptual and self-reported measures was reported in

some articles (Shanks et al., 2018; Jonnagaddala et

al., 2020) (Rogier, 2021), although argued not to be a

problem for the validity of the results.

Table 3: Contributing respondents per stakeholder group.

Stakeholder groups (sources

of data

)

Respondents Unknown

Res

p

ondents

EA 998 3x articles

IT 626 1x articles

Mixed EA & IT 145 1x articles

Mixed EA, IT & Stakeholde

r

541 1x articles

Stakeholder / Business 479 3x articles

Student 10

Undetermine

d

444 4x articles

The data were predominately reported to be

provided by EA respondents, followed by IT

respondents with prior knowledge of EA. They

answered questions about their own practice but also

about aspects that lie within other stakeholders'

spheres of interest, control and responsibility.

Five (5) papers included discussions (Lange et al.,

2016; Dang, 2021; Al-Kharusi et al., 2021) on how

stakeholders perceived a particular topic compared to

other stakeholders in their evaluative sections, where

(Plessius et al., 2014) (Alaeddini et al., 2017)

provided short evaluations. Six (6) papers (Abraham

et al., 2015; Lange et al., 2016; Jonnagaddala et al.,

2020) (M. et al., 2015; Aier, 2014; Pattij et al., 2020)

included statements that their samples were not

representative as a limitation.

However, no paper included a clear limitation that

evaluations should be attributed to relevant

stakeholders.

4.2 Practices (RQ2)

The use of practices in the evaluation was mostly not

well defined. The review of the articles revealed that

while the importance of practices was reported

(Ahlemann et al., 2021; Nikpay et al., 2017b),

practices were not found to be clearly delineated and

characterised and thus not directly considered during

the evaluations. Even when the term “practice” was

defined (Nikpay et al., 2017b), the EA

Implementation Methodology (EAIM) practice was

ENASE 2024 - 19th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

230

not distinctly defined and evaluated in detail with

respect to its parts.

A common theme found in many reviewed

articles was that factor-oriented approaches were

used in the evaluations, where factors related to

entities such as EA, IS/IT or Organisation were

identified, linked together and evaluated.

The coding, therefore, focused on identifying

clusters of activities that could be reasonably argued

to resemble and approximate practices. In many

cases, a practice was broadly referred to as ‘EA’, ‘IT’,

‘management’, ‘organisation’, or ‘project’ or a

‘service’ or ‘capability’. Table 4 presents

approximate generic and more specific practices.

Table 4: Clusters of activities that approximate practices.

Generic practices

Stakeholder, Project, Management, Business,

Organisation, Company, Customer, and External

Specific Practices

EA, Agile EA, EA Driven (Dynamic Capability), EA

Project, EA Management (Capability), EA Governance

(Capability), EA Implementation (Capability), EA

Modelling (Capability), EA Planning (Capability), Inter-

EA, EAM Infrastructure management, EA Infused

Business Project, EA Service (Capability), IT, IS

(

Ca

p

abilit

y)

, Innovation.

To determine how EA was applied in the

practices, evaluative sentences were coded. The first

coding revealed a rich language based on many

disparate aspects related to the approximated

practices. A precise coding of the aspects and level of

details was determined not to provide reliable and

valid results because each approximated practice was

defined differently, most likely because of the

article's varying focus and scope and the reliance on

factors.

In a second coding, phrases and statements in the

evaluative sentences were coded and categorised, as

exemplified in Table 5. The categories provide broad

insights into the languages used to represent

evaluations of EA.

The level of details was coded using the schema:

Generic (G) phrases that refer to a broad concept such

as ‘risk’, ‘organisation’, or ‘complexity’, Specific (S)

phrases that refer to a specific concept such as an

‘action’ or ‘noun’, and Characteristic (C) phrases that

refer to characteristics of specific concepts such as

‘feature of information product’, or a verb ‘modifier’.

The majority of the phrases were found to be (S),

followed by (G), and rarely (C), with an even

distribution amongst categories of phrases.

Table 5: Examples of categorised phrases and statements

related to how EA is used in practices.

Enable

“EA turns out to be a good instrument to enable the

organization to respond to changes in the outside world in

an agile fashion”(Foorthuis et al., 2016)

Achieve

“…EA Framework has helped the Organization in

achieving all the goals it had intended to fulfill with EA

p

ro

g

ram”

(

Qazi et al., 2019

)

Relate

“EA turns out to be a good instrument to achieve an

optimal fit between IT and the business processes it

supports.”(Foorthuis et al., 2016)

Definitional

“The roles of EA stakeholders were clearly

de

f

ined”

(

Rouhani et al., 2019

)

Have (access to)

“Appropriate infrastructure was provided for the

enter

p

rise”

(

Rouhani et al., 2019

)

Personal Attitude

“I am satisfied with the outcomes/output of the

session”

(

Nakakawa et al., 2013

)

Partici

p

ate

“The CEO must be involved” (Bernaert et al., 2016)

Do

“Project portfolio planning is effective and informed by

EA services”

(

Shanks et al., 2018

)

Use

“AEA is used to assess major project investment in

GDAD”

(

Alzoubi and Gill, 2020

)

Service

“The service quality of enterprise architecture will

p

ositively influence IT practitioners and urban

stakeholder’s intention to use EA for digitalization of

cities”

(

Anthon

y

Jnr et al., 2023

)

Result

“use our EA to adjust our business processes and the

technology landscape in response to competitive strategic

moves or market opportunities” (Rogier, 2021)

Noted is that explicit statements about the

participation of agents and IP in a practice, who uses

an IP or who co-uses an IP, were rarely found but

could, in a few cases, be inferred.

4.3 Practice Relationships (RQ3)

The review revealed that relationships between

stakeholders and their practices were not explicitly

defined and characterised, although relationships

could be derived from the evaluative sentences

covering two or more practices.

The phrase “improvement of an organizations

efficiency resulting from EAM” (Lange et al., 2016)

illustrates the implicit nature of relationships. It is

reasonable to infer that at least two practices

Review of Evaluations of Enterprise Architecture

231

(organization and Enterprise Architecture

Management (EAM)) are related, and something in

EAM leads to improving the efficiency of one or

more underdefined parts of the organisations. It is

also highly likely that ‘organisation’ is divided into a

multitude of specialised (work) practices.

Furthermore, several evaluative statements in the

articles covered long causal chains over many

relationships, such as EA-Project-Organisation-

Customer (Plessius et al., 2014).

Table 6 briefly presents key relationships between

generic practices and EA using the “⇔” separator.

Table 6: Key derived practice relationships.

EA modelling] ⇔ [IT], [EA/EAM] ⇔ [IT/IS], [EA/EAM]

⇔ [Project], [EA/EAM]⇔ [Organisation], [EA] ⇔ [IT] &

[Organisation], [EA] ⇔ [Innovation], [EA] ⇔ [External],

[EA Service] ⇔ [IT], [EA Service] ⇔ [Business project],

[EA Governance] ⇔ [IT], [EA] ⇔ [GDAD], [EA

Adoption] ⇔ [Management], [EA] ⇔ [Undetermined].

Note: GDAD - Geographically Distributed Agile

Development

No distinct aspects of the relationship were coded

due to the same reasons practice aspects were not

coded. However, underlying theories such as

institutional logic (Dang, 2021) and alignment

(Doumi, 2019) (Alaeddini et al., 2017) suggest that

there are important dynamics to consider between

specific organisational units or practices.

General roles such as stakeholder and architect

were frequently referenced but not used to

characterise agents' participation in relationships. In

two (2) articles, roles were defined: (Foorthuis et al.,

2016) defined EA creator and EA user, and (Plessius

et al., 2014) defined EA Developer, EA Applier, and

Stakeholder, which correspond to the archetypical

roles of creator, producer, and consumer (Tell and

Henkel, 2023), and not with organisational units.

4.4 Practice Accommodation (RQ4)

The fourth RQ concerns how the evaluations

examined how practices and related entities fit and

causally relate with each other, including how EA

was considered to deliver value. The effectuation

aspect was not included in this survey.

Regarding how EA delivers value, only three (3)

articles were found to be directly focusing on

evaluating ‘how’ EA delivers values, (Foorthuis et

al., 2016) (using survey questionnaires and partial

least squares (PLS) method to statistically analyse

perceptual measures and correlations/causality),

(Ahlemann et al., 2021) (using interviews and coding

of open questions and documents), and (Aier, 2014)

(survey questionnaires and partial least squares).

However, the details about ‘how’ were primarily

defined through informed reasoning and not by

formal theories of change.

Even though other articles included evaluations of

factors (what) as exemplified by - EA align business

strategies with IT resources to create competitive

advantage (Fakieh, 2020), the details of ‘what’,

’‘how’ and causality were predominately left to

informed reasoning.

No article evaluated time series, and EA

constructs such as information flow were not used in

the evaluations.

4.5 Additional Observations

EA Frameworks

An interesting observation emerged from the coding,

indicating that EA frameworks were not used to

formulate the evaluations.

Alternatives and Relative Advantages

The early coding of accommodation suggested that

the evaluations did not include alternative sources and

mechanisms that deliver the benefits of EA.

Evaluations of alternatives are suggested in the

ISO 42030 (ISO/IEC/IEEE, 2019), and relative

advantages are suggested in the diffusion of

innovation theory Field (Everett, 2003) and

acceptance of the information technology (Venkatesh

et al., 2003).

Therefore, later codlings included evaluations of

alternative methods and relative advantages.

One (1) article (Zhou et al., 2020) included an

evaluation of alternative methods for modelling EA

models (traditional .vs a method based on

ArchiMate), where a controlled experiment shows

that the proposed method has better performance than

the traditional approaches in terms of efficiency,

effectiveness, quality and experience. Furthermore,

one (1) article (Abraham et al., 2015) discussed the

malleability of boundary objects.

Situated Information Product Artefacts

The early coding of practices suggested that the

evaluations did not include the differences between

generic information products, such as EA models, and

information products that are adapted to specific

stakeholders’ work and practices.

Therefore, later codlings included evaluations of

the situating of EA information products and their

adjustment to stakeholder-specific practices.

ENASE 2024 - 19th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

232

One (1) article evaluated the malleability of

boundary objects to support overcoming pragmatic

boundaries where “A jointly transformable object

helps different communities to try out solution

alternatives and negotiate a common solution”

(Abraham et al., 2015). Otherwise, no article

evaluated the adaptation of information products to

stakeholders' unique perspectives, practices, and

relationships.

5 DISCUSSIONS AND

KNOWLEDGE GAPS

5.1 Stakeholder Contribution and

Uneven Coverage of Voice (RQ1)

The finding that stakeholders' voices were heard

unevenly and that predominately EA experts

followed by IT individuals with prior knowledge

about EA participated in evaluations raises questions

about biases and whether there is a knowledge gap in

understanding to whom and how EA delivers

organisational benefits. Interestingly, there were few

discussions about covering relevant stakeholders'

voices. Furthermore, evaluations of stakeholder

perceptions may be problematic when stakeholders

express their views of other stakeholders' interests,

control, and responsibilities. Do they have the same

beliefs, and do they agree?

Leaving stakeholders out in the evaluations of the

co-use of IP may create un(der)used IP or illusions of

success and satisfaction. The identified problems with

the co-use of models, as exemplified in “Enterprise

Modelling for the Masses – From Elitist Discipline to

Common Practice” (Sandkuhl et al., 2016) and

stakeholder engagement (Kotusev, 2019), suggest

more emphasis on including stakeholders' voices.

A theme was found where EA experts often play

multiple roles in evaluations. They build EA theories

and define evaluation questions to be answered by

either EA experts or individuals with knowledge

about EA in surveys and interviews. This further

challenges the validity of evaluative results. This also

raises questions about the balance between

participatory vs. expert evaluations and the view that

summative participatory evaluations should

complement formative expert evaluations (Sager and

Mavrot, 2021) to ensure real utility is generated for

relevant stakeholders.

5.2 EA and Use in Practices (RQ2)

The findings that stakeholder practices were

indirectly, thinly, and variably expressed posed

questions about who is doing what with what to

achieve some results and complicate the analysis and

comparison of research models and evaluations.

For example, the evaluative sentence “EA turns

out to be a good instrument to control costs.”

(Foorthuis et al., 2016) raises questions on a servicing

relationship where a generic EA is instrumental in

controlling organisational costs. Not analysing the

underlying practices leads to a number of unanswered

questions. What precisely is the source of control in

EA? Who is responsible for the costs? What costs

were considered? Who evaluated the control and

cost? What does ‘good’ mean?

The level of detail in the evaluative sentences

suggests there is a knowledge gap in evaluations of

how, in detail, stakeholders' practices and the (co-)

use of EA information products contribute to

organisational benefits, as valued by relevant

stakeholders.

5.3 Relationship Between EA and

Stakeholders Practices (RQ3)

The finding that relationships were not explicitly

defined but derived from the evaluative statements

and the research models complicates the precise

understanding of who collaborates with whom, co-

using information products, and how artefacts and

values are exchanged to deliver organisational

benefits (Tell and Henkel, 2023) to someone.

The evaluative hypothesis “Use of EA Services in

IT-Driven Change has a positive impact on Project

Benefit.” Field (Shanks et al., 2018) illustrates the

questions raised. Three distinct stakeholder practices

can be identified (EA, IT, and Project), but who and

what produces what impact, how, and what is the

utility? Were all three stakeholders' voices heard in

the evaluations? Did all stakeholders agree on the

benefits?

The findings suggest there remains a knowledge

gap in the detailed understanding of how stakeholders

explicitly collaborate, co-use IP, generate benefits for

each other, and generate aggregate utility for the

organisation in the use of EA.

5.4 EA and Effects on Stakeholder

Practices (RQ4)

The finding that few articles evaluated in detail the

what (fit) and how (mechanism) of relationships

Review of Evaluations of Enterprise Architecture

233

supports what is reported in reviewed articles "…the

EA literature is quite fragmented (individual studies

focusing on a single EA topic), often implicit (no

explicit causal models) and usually not based on

empirical data.” (Foorthuis et al., 2016), and “To

date, the causal relationships and processes behind

EAM value generation have not been studied in great

detail, nor have they been provided with a solid

theoretical foundation.” (Ahlemann et al., 2021).

Evaluative sentences such as, “EA turns out to be

a good instrument to control the complexity of the

organization.” (Foorthuis et al., 2016) raises

questions about what (cause) in EA is instrumental to

the consequences expressed by the general verb

‘control’ and noun ‘complexity’ (effect) and the

causal how (mechanism).

The findings suggest a continued knowledge gap

in the understanding and evaluation of the mechanism

of change behind the proposition that EA leads to

organisational benefits and what, in detail, fits, that

is, what the real causes/means and effects/ends are.

5.5 Additional Discussions

Alternatives and Relative Advantages

The lack of evaluations of alternatives and relative

advantages raises questions regarding what and how

could be contributing to stakeholder benefits, as

reported in “While the presented results focus on the

major causal relationships that the empirical data

uncovered, we cannot be sure that there are no other,

uncovered aspects.”(Ahlemann et al., 2021).

The finding suggests a knowledge gap in the

understanding of whether other (possibly non-EA)

IPs or services can be more acceptable and better

suited for co-use and deliver higher aggregated utility

for collaborating stakeholders. Maybe, the most

effective part of an EA model is not its content but the

discussions about what the EA model represents.

Situated Information Products

Mature companies are found to analyse the

information needs of EA stakeholders and to design

target group-specific visualisations and reports

(Ahlemann et al., 2021). Moreover, “Second, far from

all EA artefacts that proved useful in practice are

mentioned in the literature and far from all EA

artefacts described in the literature can be found in

practice, …“ (Kotusev, 2019).

In the examined evaluations, there was a lack of

discussion on how information products can be

adjusted from generic to situated. This finding and

aspects of genericity as defined in GERAM

(ISO/IEC, 2006) and situational method engineering

(Henderson-Sellers et al., 2014) suggest that there are

relevant differences between how generic IP found in

EA frameworks and specific IP products that are

adapted to stakeholders' actual jobs to be done and

needs, contribute to stakeholder benefits. The

findings suggest a knowledge gap with regard to the

evaluation of general vs specific EA information

products.

5.6 Discussions of WOA

The WOA offer a number of features that promise to

address and clarify the knowledge gaps and raised

questions outlined in sections 4.2 to 4.5, thereby

enriching EA stakeholder analysis, EA evaluations,

and the design of the (co-) use of EA information

products.

The practice orientation of WOA provides a

natural representation of stakeholder interests, such as

who is doing what” and what is in it for me.

The findings indicate that stakeholders' voices

were heard unevenly and that predominately EA

experts followed by IT individuals with prior

knowledge about EA participated in evaluations.

The voices of stakeholders can be represented by

stakeholders' ‘Participation’ in ‘Practices’ and

through the link between each descriptive sentence

and who made this sentence. These two features

provide visibility of and encourage due consideration

of stakeholders' points of view, which can improve

the design of IPs and the validity of evaluations and

enable participatory evaluations in addition to expert

evaluations. Thus, WOA can separate stakeholder

views relating to their own practices and views about

other stakeholders' spheres of interests, influence and

control.

The explicit representation of ‘Practice’ enables

representations, design, and evaluations of who does

what with whom, who said what about what and who

values what at the desired level of detail, which can

increase the understanding by and relevance to

stakeholders in their use of IPs and participation in

EA activities. The directness of practices makes it

clear to stakeholders that they should be engaged in

EA-infused activities and consider what is in it for

them.

The concept of ‘Participation’ supports the view

by Feldman and Orlikowski (Feldman and

Orlikowski, 2011)] that there is an essential

distinction between the inherent value of

technological artefacts such as IPs and the artefact-in-

use. It is the ways that artefacts are used by

stakeholder in their practices that make them

resources, valuable and meaningful for organisations.

ENASE 2024 - 19th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

234

This indicates the need to be able to evaluate both the

inherent qualities of IPs and the qualities of IPs that

participate and are used in a practice.

The richness and diversity of the languages used

to express evaluative sentences and factors are

supported by using a set of sentences from controlled

(domain-specific) languages that cover common

aspects of practices, agents, relationships, and

information products. The use of controlled

languages can simplify comparisons of EA research

models and factor evaluations.

The explicit representation of ‘Relationships’

enables the due consideration and evaluation of

stakeholders' different responsibilities and the work

they do and the representation and evaluation of

alignment and asymmetries (Donaldson and Preston,

1995) between EA and stakeholders in their practices.

Relationships provide a structure for representing and

evaluating the co-use of information products and the

calculation of aggregated utility based on each

stakeholder's view of their own use and participation

in relationships.

The explicit representation of ‘Accommodations’

encourages due consideration of visible and

formulated causal mechanisms based on theories of

change, which provides a vehicle that strengthens the

formulation of testable hypotheses and increases

rigour and specificity in representations, design and

evaluations.

The presence of longer causal (cause leads to

effect) and benefit (means leads to ends) chains in

reviewed articles and theories, such as the

institutional theory, suggests the importance of

considering networks of collaborating stakeholders.

WOA can explicitly represent networks and

information streams through relationships that can

capture the fuller dynamics of EA value-creation by

considering the interlinked practices of customers,

partners, business management, projects, IT

management, IT, EA, EA Governance, etcetera.

The explicit consideration of alternative sources

of benefits and relative advantages of IPs and EA

content can reduce uncertainty about what generates

the most benefits and subsequently improve the trust

in and qualities of EA services, methods and content.

Furthermore, WOA offers a structure to anchor

evaluative factors to stakeholders and the work they

do with others in a way that is straightforward for

stakeholders to understand and relate to.

While the WOA provides a number of features, as

outlined in this section, that address and clarify the

knowledge gaps and raised questions, it can enrich

and complement traditional factor analysis but not

fully replace factor analysis and evaluations of EA.

6 SUMMARY

This paper presents a systematic literature review on

empirical evaluations of EA that aims to gain insights

into aspects related to stakeholder practices and

relationships that were considered essential to

evaluate and how different stakeholders contributed

to evaluations of EA. The SLR aim to inform the

design and improvement of the WOA.

The main knowledge contributions are, firstly,

that stakeholders' voices were heard unevenly and

that predominately EA experts followed by IT

individuals with prior knowledge about EA

participated in evaluations, raising challenges about

biases and validity in evaluation results. Secondly,

stakeholder practices, relationships, and

accommodations were not clearly delineated, directly

defined and evaluated, suggesting that there are

knowledge gaps and questions in the detailed

understanding of who does what and co-using what,

what impacts what and who evaluates what. Thirdly,

few articles evaluated ‘how’ something (‘what’) in

EA in detail delivers benefits, suggesting a continued

knowledge gap. Fourthly, alternative sources of

benefits and relative advantages of IPs and EA

content were not evaluated, raising the possibility that

new sources of benefit could be created or other

existing sources should be identified.

The findings indicate that WOA includes features

that can address issues with the participation of

stakeholders, knowledge gaps, and raised questions,

and enrich EA stakeholder analysis, evaluations of

EA, and IP design by including representations of

stakeholders' voices, practices, relationships,

accommodation and co-use of IP at the desired level

of detail.

Based on the findings, it is recommended that

summative participatory evaluations complement

formative expert evaluations (Sager and Mavrot,

2021) to ensure that real and aggregated utility is

generated and evaluated by relevant stakeholders.

Limitations and areas for future work. A

grammatical analysis and detailed coding were not

performed on evaluative sentences, leaving

uncertainties in the identified aspects, which can be

addressed as future work to build controlled

languages enabling representations of common

aspects of practices, such as decisions, activities,

needs, access to data, data provenance and uses of

IPs, at the desired level of detail.

Another future work involves identifying

common practices and relationships related to EA.

The derived relationships can be viewed as

forming workflows, streams and causal networks that

Review of Evaluations of Enterprise Architecture

235

could, as future work, be identified and more

precisely evaluated considering stakeholders' actual

practices, exchanges and co-use of IP. Moreover,

archetypical EA benefit networks could be identified

based on practice networks, which can be used as

comparative baseline(s) for constructing new and

comparing EA evaluation studies.

Theories of (social) qualities of ‘co-use’ and

‘aggregated utility’ could be developed and added to

the toolbox of EA stakeholder analysis and

evaluations.

The WOA offers a practice-oriented approach,

which differs from factor-oriented evaluations. An

analysis of the relative advantages of the practice vs.

factor approaches could forward knowledge on how

to evaluate the benefits of EA considering the utilities

for each stakeholder and aggregated utility in

relationships and networks. On this theme, an

interesting combination of the factor and practice

approaches includes the evaluation of factors that are

associated with practices and other parts of WOA.

REFERENCES

Abraham, R., Aier, S. & Winter, R. (2015) Crossing the

Line: Overcoming Knowledge Boundaries in

Enterprise Transformation. Busin. Info. Sys. Eng., 57.

Ahlemann, F., Legner, C. & Lux, J. (2021) A resource-

based perspective of value generation through

enterprise architecture management. Inf. Manage, 58,

Ahmad, N.A., Drus, S.M. & Kasim, H. (2020) Factors That

Influence the Adoption of Enterprise Architecture by

Public Sector Organizations: An Empirical Study. IEEE

Access, 8, 98847-98873.

Aier, S. (2014) The role of organizational culture for

grounding, management, guidance and effectiveness of

enterprise architecture principles. Inf. Syst. eBus.

Manage, 12, 43-70.

AIS (2023) Senior Scholars’ List of Premier Journals.

Senior Scholars’ List of Premier Journals,

Al-Kharusi, H., Miskon, S. & Bahari, M. (2021) Enterprise

architects and stakeholders alignment framework in

enterprise architecture development. Inf. Syst. e-Bus.

Manage., 19, 137-181.

Alaeddini, M. et al. (2017) Leveraging business-IT

alignment through enterprise architecture - an empirical

study to estimate the extents. Information Technology

and Management, 18, 55-82.

Alzoubi, Y.I. & Gill, A.Q. (2020) An Empirical

Investigation of Geographically Distributed Agile

Development: The Agile Enterprise Architecture is a

Communication Enabler. IEEE Access, 8.

Tell, A.W. & Henkel, M. (2023) Enriching Enterprise

Architecture Stakeholder Analysis with Relationships.

22nd International Conference on Perspective in

Business Informatics Research (BIR2023).

Anthony Jnr, B., Petersen, S.A. & Krogstie, J. (2023) A

model to evaluate the acceptance and usefulness of

enterprise architecture for digitalization of cities.

Kybernetes, 52, 422-447.

Bernaert, M. et al. (2016) CHOOSE: Towards a metamodel

for enterprise architecture in small and medium-sized

enterprises. Inf. Syst. Front., 18, 781-818.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in

psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-

101.

Bueger, C. & Gadinger, F. (2014) International Practice

Theory: New Perspectives. PALGRAVE

MACMILLAN,

(UK), C.F.R.A.D. (1995) Database of Abstracts of Reviews

of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews.

Clark, A.E., Friese, C. & Washburn, R.S. (2018) Situational

analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn.

Sage Publications,

Dang, D. (2021) Institutional Logics and Their Influence on

Enterprise Architecture Adoption. Journal of Computer

Information Systems, 61, 42-52.

Dearing, J.W. & Cox, J.G. (2018) Diffusion Of Innovations

Theory, Principles, And Practice. Health Affairs, 37.

Donaldson, T. & Preston, L.E. (1995) The Stakeholder

Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and

Implications. The Academy of Management Review, 20.

Doumi, K. (2019) Evolution of business it alignment: Gap

analysis. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences,

14, 1211-1218.

Everett, M.R. (2003)

Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition.

Free Press,

Fakieh, B. (2020) Enterprise Architecture and

Organizational Benefits: A Case Study. Sustainability,

12, 8237.

Feldman, M.S. & Orlikowski, W.J. (2011) Theorizing

Practice and Practicing Theory. Organization Science,

22, 1240-1253.

Foorthuis, R. et al. (2016) A theory building study of

enterprise architecture practices and benefits. Inf. Syst.

Front., 18, 541-564.

Freeman, R.E. (2010) Strategic Management: A

Stakeholder Approach. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Henderson-Sellers, B. et al. (2014) Situational Method

Engineering. Springer,

INCOSE (2023) Guide to the Systems Engineering Body of

Knowledge. 2023,

ISO/IEC (2006) 19439:2006 Enterprise integration -

Framework for enterprise modelling.

ISO/IEC (2015) 9000 Quality management systems‚

Fundamentals and vocabulary. 1 - 60.

ISO/IEC/IEEE (2019) 42030:2019 Architecture evaluation

framework. 42030:2019,

ISO/IEC/IEEE (2022) 42010:2022 Architecture

description. 42010:2022,

Jonnagaddala, J. et al. (2020) Adoption of enterprise

architecture for healthcare in AeHIN member countries.

BMJ Health and Care Informatics, 27,

Kaddoumi, T. & Watfa, M. (2022) A foundational

framework for agile enterprise architecture.

ENASE 2024 - 19th International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering

236

International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 13, 136-155.

Kitchenham, B. (2007) Guidelines for performing

Systematic Literature Reviews in Software

Engineering.

Kotusev, S. (2019) Enterprise architecture and enterprise

architecture artifacts: Questioning the old concept in

light of new findings. Journal of Information

Technology, 34, 102-128.

Lange, M., Mendling, J. & Recker, J. (2016) An empirical

analysis of the factors and measures of Enterprise

Architecture Management success. Eur. J. Inf. Syst., 25,

411-431.

M., L. & B., B. (2018) A Model-Based Method for the

Evaluation of Project Proposal Compliance within EA

Planning. 2018 IEEE 22nd International Enterprise

Distributed Object Computing Workshop (EDOCW).

M., N. et al. (2015) How Does Enterprise Architecture

Support Innovation. 2015 International Conference on

Enterprise Systems (ES), 192-199.

Mirsalari, S.R. & Ranjbarfard, M. (2020) A model for

evaluation of enterprise architecture quality. Evaluation

and Program Planning, 83,

Myers, M.D. (2009) Qualitative Research in Business &

Management. Sage Publications Ltd,

N., R. & J., D. (2014) Application of a lightweight

enterprise architecture elicitation technique using a case

study approach. 2014 9th ENASE, 1-10.

Nakakawa, A., Bommel, P.V. & Proper, H.A.E. (2013)

Supplementing enterprise architecture approaches with

support for executing collaborative tasks - A case of

TOGAF ADM. Int. J. Coop. Inf. Syst., 22,

Nicolini, D. (2012) Practice Theory, Work, and

Organization: An Introduction. Oxford University

Press,

Niemi, E.I. & Pekkola, S. (2016) Enterprise architecture

benefit realization: Review of the models and a case

study of a public organization. Data Base for Advances

in Information Systems, 47, 55-80.

Nikpay, F., Ahmad, R. & Yin Kia, C. (2017a) A hybrid

method for evaluating enterprise architecture

implementation. Eval. Program Plann., 60, 1-16.

Nikpay, F. et al. (2017b) An effective Enterprise

Architecture Implementation Methodology. Inf Syst e-

Bus Manage, 15, 927-962.

Nor, A.A., Sulfeeza, M.D. & Kasim, H. (2021) The Effect

of Multidimensional Factors on Organizational

Adoption of Enterprise Architecture: The Moderating

Role of Organization Type. Journal of Physics:

Conference Series, 1962,

Group, O.M. (2019) Semantics of Business Vocabulary and

Business Rules (SBVR) v1.5.

Osterwalder, A. et al. (2015) Value proposition design:

How to create products and services customers want.

John Wiley Sons,

Pattij, M., Van de Wetering, R. & Kusters, R.J. (2020)

Improving Agility Through Enterprise Architecture

Management: The Mediating Role of Aligning

Business and IT. AMCIS,

Perez-Castillo, R. et al. (2021) ArchiRev - Reverse

engineering of information systems toward ArchiMate

models. An industrial case study. Journal of Software:

Evolution and Process

, 33,

Plessius, H., van Steenbergen, M. & Slot, R. (2014)

Perceived Benefits from Enterprise Architecture.

MCIS, 23,

Qazi, H. et al. (2019) A Detailed Examination of the

Enterprise Architecture Frameworks Being

Implemented in Pakistan. International Journal of

Modern Education and Computer Science, 11, 44.

R., E., C., S. & R., B. (2020) Current Practices in the Usage

of Inter-Enterprise Architecture Models for the

Management of Business Ecosystems. 2020 IEEE 24th

International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing

Conference (EDOC), 21-29.

Rogier, V.D.W. (2021) Understanding the Impact of

Enterprise Architecture Driven Dynamic Capabilities

on Agility: A Variance and fsQCA Study. Pacific Asia

Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13.

Rouhani, B.D. et al. (2019) Critical success factor model

for enterprise architecture implementation. Malaysian

Journal of Computer Science, 32, 133-148.

Sager, F. & Mavrot, C. (2021) Participatory vs expert

evaluation styles. Sage Handbook of Policy Styles,

London: Routledge,

Sandkuhl, K. et al. (2016) Enterprise Modelling for the

Masses – From Elitist Discipline to Common Practice.

In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing:

The Practice of Enterprise Modeling, Springer

International Publishing, Cham, pp. 225-240.

Shanks, G. et al. (2018) Achieving benefits with enterprise

architecture. The Journal of Strategic Information

Systems, 27, 139-156.

Tell, A. (2023) A Situating Method for Improving the

Utility of Information Products. 25th International

Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, ICEIS,

2, 589-599.

Tell, A.W. (2018) Designing Situated Capability

Viewpoints: Adapting the general concept of capability

to work practices. Stockholm University.

Tell, A.W. & Henkel, M. (2018) Capabilities and Work

Practices - A Case Study of the Practical Use and

Utility. World Conference on Information Systems and

Technologies, 1152 - 1162.

Ulwick, A.W. (2016) Jobs to be done: theory to practice.

Idea Bite Press,

Venkatesh, V. et al. (2003) User Acceptance Of

Information Technology - Toward A Unified View.

MIS Quarterly, 27, 425-478.

Zhou, Z. et al. (2020) IMAF: A Visual Innovation

Methodology Based on ArchiMate Framework. Int. J.

Enterp. Inf. Syst., 16, 31.

Review of Evaluations of Enterprise Architecture

237