From Theory to Training: Exploring Teachers' Attitudes Towards

Artificial Intelligence in Education

Cecilia Fissore

a

, Francesco Floris

b

, Valeria Fradiante

c

, Marina Marchisio Conte

d

and Matteo Sacchet

e

Department of Molecular Biotechnology and Health Sciences, University of Turin, Via Nizza 52, 10126, Turin, Italy

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Didactic Activities, Mathematics, Primary School, Secondary School, Teacher

Training.

Abstract: Every year, there is increasing interest in applying Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms and systems in

education. Educating students about the conscious use of AI and its challenges is essential. Still, even before

that, it is necessary to educate teachers who need to acquire the necessary skills to use these technologies in

the classroom to enrich their students' learning experience. Training must be theoretical and guide teachers in

designing educational activities with AI, about AI, and preparing for AI. This article presents research

conducted in Italy to understand educators' attitudes toward AI in Education. Responses to a nationwide

questionnaire are analysed to understand the relationship between teachers at all levels of schooling and AI.

The results show that teachers need more confidence in their AI skills but are also not too concerned about

the increasing spread of AI at various levels. From the findings, we can also say that AI has found little space

in the school activities of Italian teachers. At the same time, teachers state that they urgently need to be trained

on AI issues.

1 INTRODUCTION

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a “booming

technological domain capable of altering every aspect

of our social interactions” (Pedro et al., 2019; p. 6)

and it now plays a significant role in multiple facets

of everyday life, as well as in all education levels.

The application of AI algorithms and systems in

education is gaining more and more interest every

year. According to Chassignol et al. (2018), AI in

education has been integrated into administration,

teaching or instruction, and learning. As education

evolves, researchers are trying to apply advanced AI

techniques, such as deep learning, data mining, and

learning analytics, to address complex problems and

customise teaching methods for individual students

(Floris et al., 2022; Fissore et al., 2023a). AI-enabled

education provides timely and personalised

instruction and feedback for both teachers and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8398-265X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0856-2422

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7647-1050

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1007-5404

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5630-0796

learners (Chen et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2018).

Intelligent education systems are designed to improve

the value and efficiency of learning through various

computing technologies, especially those related to

machine learning (Kahraman et al., 2010), which are

closely related to statistical models and cognitive

learning theory.

AI can transform teaching and learning at all

levels of education and in different fields, for

example: AI to support collaborative learning; AI to

support problem solving (Barana et al., 2023); AI-

driven monitoring of student forums; AI to support

continuous assessment; AI learning companions for

students; AI teaching assistants for teachers; AI to

advance learning sciences (i.e. to help us better

understand learning) (Holmes et al., 2023). However,

as highlighted by Holmes et al. (2023), there is also

little robust evidence about the effectiveness of the

rapidly growing number of AI tools in education.

118

Fissore, C., Floris, F., Fradiante, V., Marchisio Conte, M. and Sacchet, M.

From Theory to Training: Exploring Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence in Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0012734700003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 2, pages 118-127

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Even where there is some evidence, it has typically

been compared to business as usual, rather than to

another technology with at least some degree of

comparability. The purported effectiveness of many

other tools may be due to their novelty in the

classroom rather than having anything to do with the

AI used. This is despite the fact that most studies of

AI in education are concerned with university

learning and teaching.

Several systematic reviews have been conducted

by different research teams to highlight the common

problem in AI in education, namely the lack of

connection between AI techniques and theoretical

underpinnings, which in turn critically influences the

impact of AI implementations in education (Ouyang

& Jiao, 2021). The use of AI in education is

characterised on the one hand by the ease with which

students can access AI-based tools, both for

educational purposes and in everyday life, and by the

difficulty for teachers to explain the mechanisms and

technologies behind them, given their complexity. It

is essential to train teachers in the theoretical concepts

related to these issues, but above all in the planning

of didactic activities using innovative pedagogical

approaches (Fissore et al., in press).

However, in order to plan effective and usable

training actions for teachers in their daily teaching, it

is necessary to understand the starting point,

especially concerning primary and secondary

schools. In fact, it is important to understand the

relationship of Italian teachers with AI: how much

they know about it, how much they are interested in

knowing about it, how much they talk about AI with

students, how much they use itboth in and out of

class, how much they are interested in using it, with

what frequency, how the use of AI is regulated in their

school, and much more.

This paper presents part of the results of a survey

proposed to Italian teachers of all levels and

disciplines from October 2023 to January 2024,

entitled "AI and Gamification in education". The

survey was carried out among participants of the

PP&S - "Problem Posing and Solving" – an initiative

dedicated to the integration of advanced technologies

and methods, such as artificial intelligence and

gamification, in education in Italy. The PP&S

(available at www.progettopps.it), led by the Italian

Ministry of Education, has been promoting, since

2012, the training of Italian lower and upper

secondary school teachers in innovative teaching

methods and the use of technologies as essential tools

for professional growth and for improving teaching

and learning (Barana et al., 2020; Fissore et al.,

2023b). The survey has also been also fundamental

for collecting observations, suggestions, and ideas for

the preparation of future training activities of the

project.

In this paper we focus on AI in education, starting

with the following research questions:

(RQ1) How confident are Italian teachers about

AI?

(RQ2) How much do Italian teachers use AI in

education?

(RQ3) How interested are Italian teachers in

receiving training on AI in education?

The survey involved 255 teachers. The state-of-

the-art section provides an introduction to the topic of

AI in education and teacher training on it. The

“Methodology” section presents the research

methodology, i.e. the structure of the questionnaire,

the different types of questions, and how they were

analysed. The section “Results” shows data and

statistics based on teachers’ responses. In the

“Conclusions” section, based on the results of the

research, a design of training interventions aimed at

integrating advanced technologies and

methodologies, such as Artificial Intelligence, into

training in Italy is proposed. Finally, final remarks are

discussed.

2 STATE OF THE ART

2.1 Definition of AI

Despite the increased interest in AI by the academic

world, industry, and public institutions, there is no

standard definition of what AI actually involves

(Samoili et al., 2020). Definitions of AI multiplied

and expanded, often becoming entangled with the

philosophical questions of what constitutes

“intelligence” and whether machines can really be

“intelligent” (Miao et al., 2021). For example, Zhong

(2006, p. 90) defined AI as “a branch of modern

science and technology aimed at the exploration of

the secrets of human Intelligence ”n on’ hand and the

transplantation of human intelligence to machines as

much as possibile on the other hand, so that machines

would be able to perform functions as intelligently as

they can”. Luckin et al. (2016) defined IA as a

computer system that has been designed to interact

with the world through capabilities that we usually

think of as human. The definition provided by the

European AI Strategy is: “Artificial Intelligence

refers to systems that display intelligent behaviour by

analysing their environment and taking action — with

some degree of autonomy — to achieve specific

goals” (EC Communication, 2018). Chassignol et al.

From Theory to Training: Exploring Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence in Education

119

(2018) provide a two-faceted definition and

description of AI. They define AI as a field and as a

theory. As a field, they define AI as an area of study

in computer science that aims to solve various

cognitive problems commonly associated with

human intelligence, such as learning, problem

solving, and pattern recognition, and subsequent

adaptation. As a theory, they define AI as a theoretical

framework that guides the development and use of

computer systems with human capabilities,

particularly intelligence, and the ability to perform

tasks that require human intelligence, including visual

perception, speech recognition, decision making, and

translation between languages.

In general, from these definitions and

descriptions, AI encompasses the development of

machines that have some level of intelligence, with

the ability to perform human-like functions, including

cognition, learning, decision making, and adaptation

to the environment. As such, some specific

characteristics and principles emerge as key to AI.

Intelligence, or the ability of machines to demonstrate

some level of intelligence and perform a wide range

of functions and capabilities that require human-like

abilities, emerges from this definition and discussion

of AI as a key characteristic of AI (Chen et al., 2020).

AI research is concentrated on various

components of intelligence, including learning,

reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and

language usage (Pedro et al., 2019). A more detailed

definition is provided by UNESCO's World

Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge

and Technology (COMEST), which describes AI as

machines capable of mimicking certain

functionalities of human intelligence, including

features such as perception, learning, reasoning,

problem solving, language interaction, and even the

production of creative works (COMEST, 2019).

Samoili et al. (2020) present a collection of key

definitions of AI to define an AI taxonomy. The

keywords identified as most relevant within each AI

domain (Reasoning; Planning; Learning;

Communication; Perception; Integration and

Interaction Services; Ethics and Philosophy) were

presented together with the operational definition.

This list of keywords is intended to be dynamically

updated according to new technological

developments in core and transversal domains, and to

be consistent with alternative proposals.

Definitions of AI are also changing depending on

what is being considered, such as the role of people,

especially younger generations , in using AI and

developing their awareness. According to the

UNICEF definition: "AI refers to machine-based

systems that, given a set of human-defined goals, can

make predictions, recommendations or decisions that

influence real or virtual environments" (Dignum et

al., 2021). When using AI tools, it is important to be

aware that AI systems work by following rules, by

learning from examples (supervised or unsupervised),

or by trial and error (reinforcement learning). By

recognising patterns in data, computers can process

text, speech, images, or video and plan and act

accordingly. For this reason, it is important to talk

about other related issues, such as the conscious use

of AI, the protection of personal data, bias, the ethics

of AI, and more.

According to Luckin & Holmes (2016), even

experts find it difficult to define AI. One reason is

that what AI includes is constantly shifting. Another

reason is the interdisciplinary nature of the field.

Anthropologists, biologists, computer scientists,

linguists, philosophers, psychologists, and

neuroscientists all contribute to the field of AI, and

each group brings its own perspective and

terminology.

2.2 Teacher Training on AI in

Education

AI has given rise to novel teaching and learning

solutions in education, which are currently being

evaluated in various settings. In particular, the

literature on AI in education has grown with the

introduction of artificial intelligence-based chatbots,

such as ChatGPT. ChatGPT has the potential to serve

as an assistant for teachers and a virtual tutor for

students, but there are challenges associated with its

use. Immediate steps should be taken to train

instructors and students to respond to the impact of

ChatGPT on the educational environment (Lo, 2023).

Nevertheless, research into AI in education goes

back several years. The earliest notable AI efforts in

educational technology for education materialised in

the early 1970s. Balacheff (1993) argued that the

main advantage of AI in mathematics education is its

ability to provide concepts, methods, and tools for

designing adaptable and appropriate computerised

systems for educational purposes.

The relationship between AI and education covers

three areas:

• Learning with AI, which involves the use of

AI-powered tools in the classroom;

• Learning about AI, which involves the study

of its technologies and techniques;

• Preparing for AI, which involves enabling all

citizens to gain a better understanding of the

potential impact of AI on human life.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

120

According to Fissore et al. (in press), the use of AI

in education is characterised by a large gap between:

• The ease of use of AI-based tools (for

educational purposes, but also in other

aspects of daily life) and, consequently, their

widespread use by students;

• The difficulty for teachers to explain the

mechanisms and technologies behind them,

given their complexity.

The skills required to adopt, use, and interact with

AI tools are many, such as:

• Basic knowledge of AI;

• Ability to use mobile devices or smartphones;

• Analytical skills, problem solving, critical

thinking and judgement;

• Creativity, communication, teamwork,

multitasking.

For this reason, it is essential to focus not only on

improving the skills of teachers in schools, but also

on revising the structure of the school curriculum. At

the same time, it is important to train teachers not only

in the theoretical content related to these topics, but

also in the planning of didactic activities in order to

adopt innovative pedagogical approaches (Fissore et

al., 2022).

There are many challenges and policy

implications that should be part of global and local

conversations about the opportunities and risks of

introducing AI into education and preparing students

for an AI-powered context. A key challenge is to

prepare teachers for AI-powered education while

preparing AI to understand education, but this must

be a two-way street (Gocen & Aydemir, 2020).

Teachers need to learn new digital skills to use AI in

a pedagogical and meaningful way, and AI

developers need to learn how teachers work and

create solutions that are sustainable in real-world

environments. Another important challenge is to

make research on AI in education meaningful. While

it is reasonable to expect that research on AI in

education will increase in the coming years, it is

worth remembering that the education sector has

struggled to take stock of educational research in a

way that is meaningful for both practice and policy-

making (Gocen & Aydemir, 2020).

The use of AI in education should be regulated at

the national level, and teachers should be provided

with guidelines to help them introduce AI tools into

everyday teaching. The Digital Education Action

Plan 2021-2027, a policy initiative of the European

Union, introduces AI as a key issue and emphasises

the need to update digital literacy curricula to reflect

this new reality. Two actions (Action 6 and Action 8)

aim to ensure that the use of AI and data in education

is conducted ethically and that educators are equipped

with the necessary skills to integrate these

technologies effectively. In Italy, the report

'Proposals for an Italian Strategy for Artificial

Intelligence' (Ministry of Economic Development,

2020) highlights the strategy's strong emphasis on

education, skills, and lifelong learning. The report

states that training people with digital skills is a

fundamental requirement for this transformation,

with AI playing a prominent role. However, it does

not provide any guidelines or regulations for schools.

3 METHODOLOGY

The idea for this national survey came from previous

teacher training experiences on AI in education

within the PP&S project, such as immersive

workshops and open online courses (Fissore et. al.,

2022). The survey was initially distributed among the

community of teachers gravitating around the PP&S

project, but then it was spread to all Italian teachers

through the communication line of the projects that

the research group manages with the schools. We also

asked teachers to distribute the survey among

colleagues. The results showed that teachers are

extremely interested in AI in education, but at the

same time, they have a great need for support and

training in the use of AI in education and the design

of effective teaching activities. Before designing new

training actions aimed at different aspects of AI

(knowledge of AI, use of AI in education, possible

implications of AI in education, etc.), it was necessary

to understand the national scenario of AI in Italian

schools.

The questionnaire is aimed at Italian teachers of

all subjects, from primary to upper secondary school.

The survey is still open, but the responses received

from 17 October 2023 to 31 January 2024 are taken

into account. The responses of 255 teachers were

considered.

The questionnaire is characterised by open

questions, Likert scale questions, multiple choice

questions, and open-ended questions.

The part of the questionnaire considered in this

research is structured in 3 stages:

• Teachers' personal data: age, gender,

discipline they teach, name of the school they

teach in, type of school, region, years of

teaching;

• Background on AI: personal thoughts about

AI, the frequency of using AI for personal

use, the knowledge about AI and AI in

education, considerations about the

From Theory to Training: Exploring Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence in Education

121

proliferation of AI, school policies and

guidelines on the use of AI, the frequency of

using AI with students;

• Teachers' considerations on their training on

AI: their needs, the areas of AI where training

is most required, and the development of

educational activities that cover the three

areas: learning with AI, learning about AI,

preparing for AI.

Descriptive statistics utilizing mean and standard

deviation were employed in the analysis of Likert

scale questions.

4 RESULTS

To answer the research questions, we considered the

255 responses from the national survey. The majority

of teachers surveyed are women (75.7%). Moreover,

most respondents are elderly teachers, since 50.4%

are over 50 years old and 25.3% are in the range 40-

50 years old. Only 12.6% are between 30 and 40 years

old and 11.7% are under 30. These first two results of

the national survey are in line with the periodic

reports on the Italian education system (OECD, 2023)

which highlights the predominance of women and

older teachers in the Italian school context. On the

other hand, older age is associated with more teaching

experience; in fact, more than half of teachers

(52.2%) have taught for more than 15 years. The

teachers surveyed are from primary (6.3%), lower

secondary (44.7%), and upper secondary (49%)

schools. In addition, 67.4% are STEM teachers. The

sample of teachers considered is almost entirely

representative of all regions of Italy (16 out of 20)

even if a major part of teachers come from Piedmont

(65.9%). The success of the initiative in Piedmont

may also be attributed to the close collaboration

between the University of Turin and local schools in

the context of the PP&S Project.

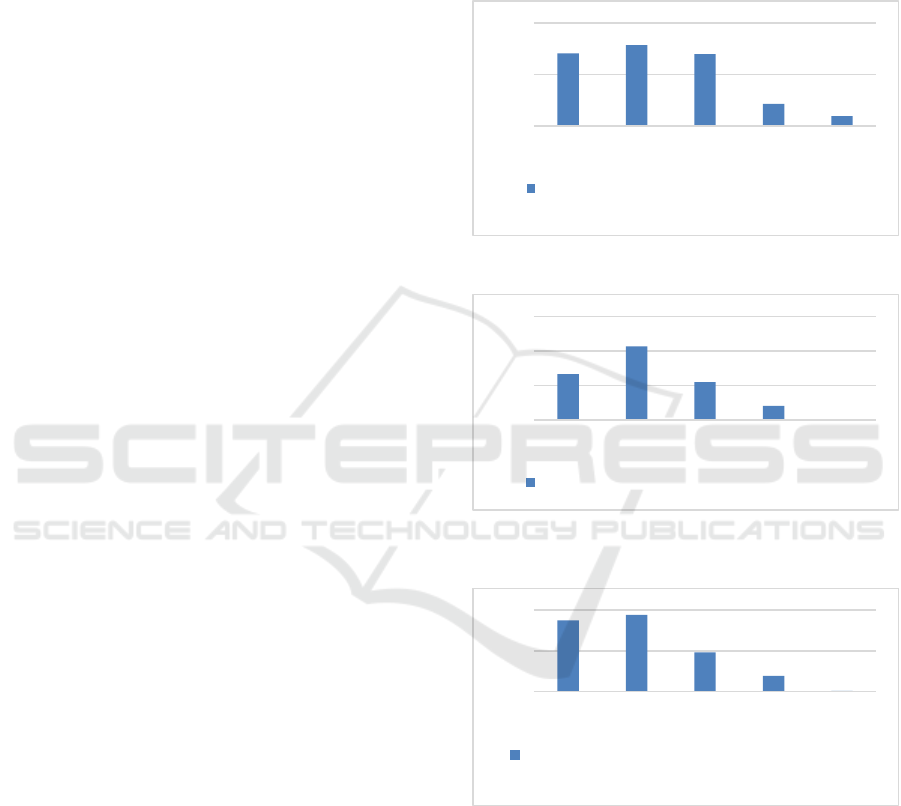

Regarding the AI background of the respondents,

34.1% of them have already attended AI training

courses. The graph in Figure 1 shows that there are

relatively few teachers who frequently use AI for

personal use on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5

(very much). This is probably due to their fear and

low confidence in their abilities and knowledge of AI

as emerged in Figure 2 and Figure 3. In fact, on the

same Likert scale, the mean obtained for the questions

"How confident are you in your knowledge of AI?”

and "How confident are you in your knowledge of AI

applications in education?” are respectively 2.13 and

2.01. This is consistent with the fact that if teachers

are not confident in their knowledge and the use of

AI, they will also lack confidence in applying AI in

education. In this sense, it can be noticed that the

graphs in Figure 2 and Figure 3 follow a similar trend,

with the only difference being that for the second

question there were more responses with a value of 1

(not at all) instead of 2 (not much) than for the first

question.

Figure 1: Frequency of teachers' self-use of AI technology.

Figure 2: Teachers' level of confidence in their knowledge

of AI.

Figure 3: Teachers' level of confidence in their knowledge

of AI applications in education.

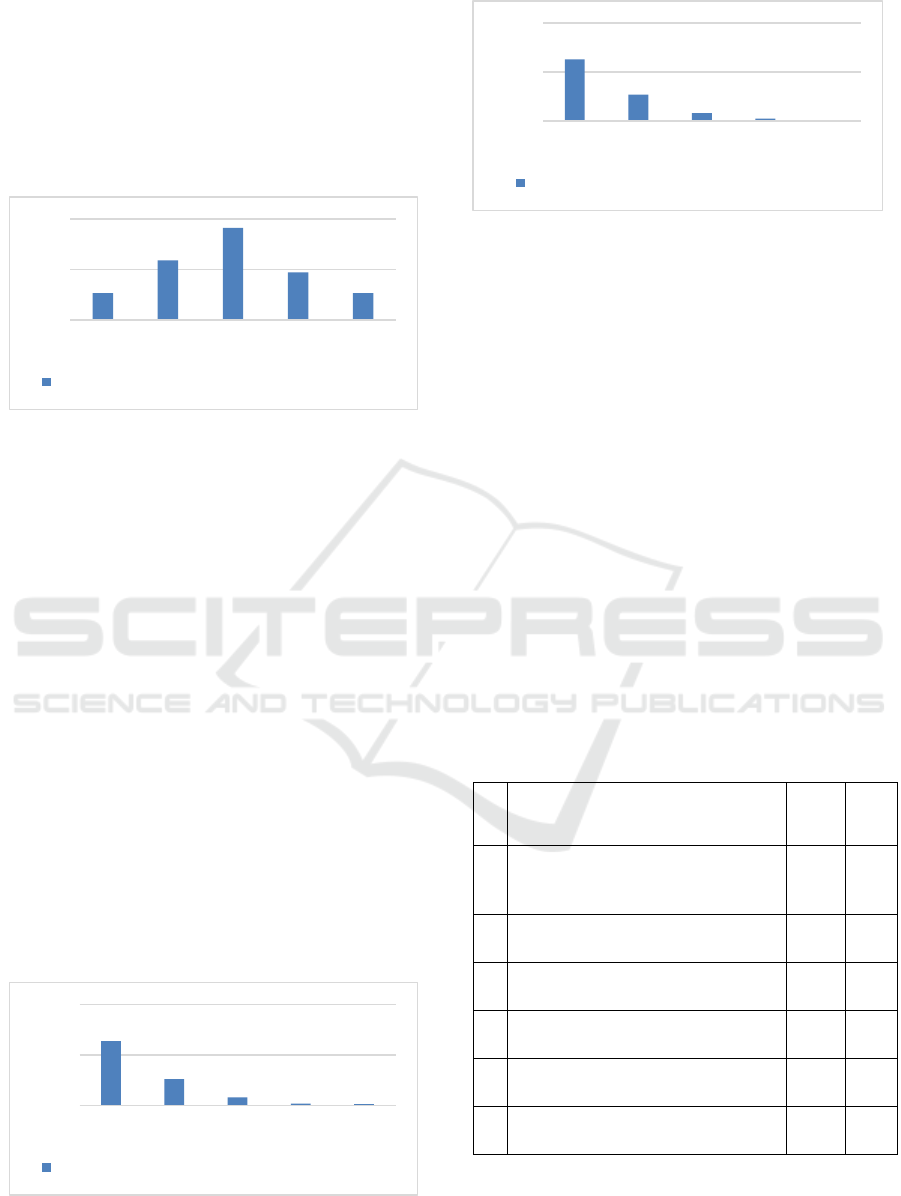

Surprisingly, although teachers are not sure of

their skills in the field of AI, they do not appear to be

too worried about the growing prevalence of AI in

various fields. In fact, the answer to the question

"How worried are you about the growing presence of

AI in many fields?", given on a scale from 1 (not at

all) to 5 (very much) received an average value of

2.95 with a standard deviation of 1.13. Figure 4 shows

0%

20%

40%

12345

How often do you use AI-based technologies for

personal use?

0%

20%

40%

60%

12345

How confident are you in your knowledge of AI?

0%

20%

40%

12345

How confident are you in your knowledge of AI

applications in education?

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

122

the frequency of answers to this question on a Likert

scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). It is possible

to notice that 3 is the most frequent value, and the

number of responses “2” is higher than the number of

responses “4”, the number of “1” and “5” is exactly

the same. It means that teachers are moderately

worried about the massive diffusion of AI in various

sectors, including education.

Figure 4: Frequency of teachers' concerns about the spread

of AI in different areas.

This last result becomes even more significant

when we combine it with the fact that 96.1% of

teachers stated that the school in which they work

does not follow specific guidelines on the use of AI.

This aspect could have caused further apprehension

among teachers, who despite the lack of clarity on the

use of AI in different areas, do not seem to be too

worried about its spread in the educational context. In

addition, only 11.4% of respondents said that the

school where they work encourages the use of AI-

based applications in the classroom. This aspect could

be the basis for the low use of AI in education by

teachers, as they are not stimulated by their schools to

include AI technologies in their teaching practices. In

addition, teachers may be concerned about the use of

unregulated AI by students and the use of their data,

as they are mostly minors. As shown in Figure 5 and

Figure 6, 63.5% of teachers never use AI in their

didactics and 62.7% of them never teach their

students to use AI in the classroom (on a scale of

1=never to 5=always).

Figure 5: Frequency of teachers’ use of AI in their didactic

activities.

Figure 6: How often teachers introduce their students to the

use of AI in the classroom.

Although teachers are not used to employing AI

in their daily activities with the students, almost all of

them (90.6%) agree that it is important for students to

learn to recognise AI and its applications in everyday

life. They also agreed (86.6%) that it is important for

students to have a deep understanding of AI.

Regarding teachers' needs for training on AI

topics, the majority of them (70.6%) stated that they

feel a strong need for AI training while 21.5% think

that it would be beneficial and 7.9% think that it is not

so urgent. In addition, the number of teachers who

expressed a need for educational activities on AI to be

offered to their students was also high (61.2%). In

particular, Table 1 shows teachers' opinions on their

needs for training in AI. For each sentence, they were

asked to indicate how much they agreed on a Likert

scale from 1=“Completely disagree” to

5=“Completely agree. Table 1 shows the mean and

standard deviation (SD) obtained for each question.

Table 1: Teachers' considerations on their training on AI.

How much do you agree with the

following statements about AI:

Mean SD

Q1 It is important for teachers to learn

how to recognise AI and its

a

pp

lications in ever

y

da

y

life.

4.3 0.72

Q2 Teachers must learn to understand

AI.

4.3 0.70

Q3 Learning the ethics of AI is

im

p

ortant fo

r

teachers.

4.5 0.67

Q4 Teachers need to design didactic

activities with AI.

3.3 0.99

Q5 It is important for teachers to design

didactic activities about AI.

3.6 0.94

Q6 It is important for teachers to design

didactic activities to

p

re

p

are fo

r

AI.

3.8 0.94

From Table 1, we can see that teachers perceive a

greater need to learn about AI and recognise its areas

of application and the issues related to its ethics. In

fact, the answers to the first three questions

0%

20%

40%

12345

How often do you use AI in your teaching activities?

0%

50%

100%

12345

How often do you use AI in your teaching activities?

0%

50%

100%

12345

How often do you teach your students to use AI?

From Theory to Training: Exploring Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence in Education

123

concerning AI general features obtained an average

score between 4.3 and 4.5. Similarly, within the three

areas identified above: Learning with AI, Learning

about AI, Preparing for AI, it can be noted that it is

more urgent for teachers to design teaching activities

that prepare students for AI (3.8) and include the

study of its technologies and techniques (3.6).

Therefore, for teachers, before designing didactic

activities that involve the use of AI (3.3), it is

necessary to develop materials that enable them to

gain a better understanding of AI. This result shows

that if teachers do not feel confident about how a tool

works, they will not feel confident about using it with

students. This may be a good general rule. However,

a deep understanding of AI requires deep skills. AI

tools are used every day by people who do not have

many digital skills. Teachers do not necessarily need

to be computer scientists to be able to design activities

that use AI, but they can engage with their students

with a basic understanding of AI. In this case, the

difficulty may lie in the paradigm shift between the

teacher as a dispenser of knowledge and the teacher

as a facilitator of learning.

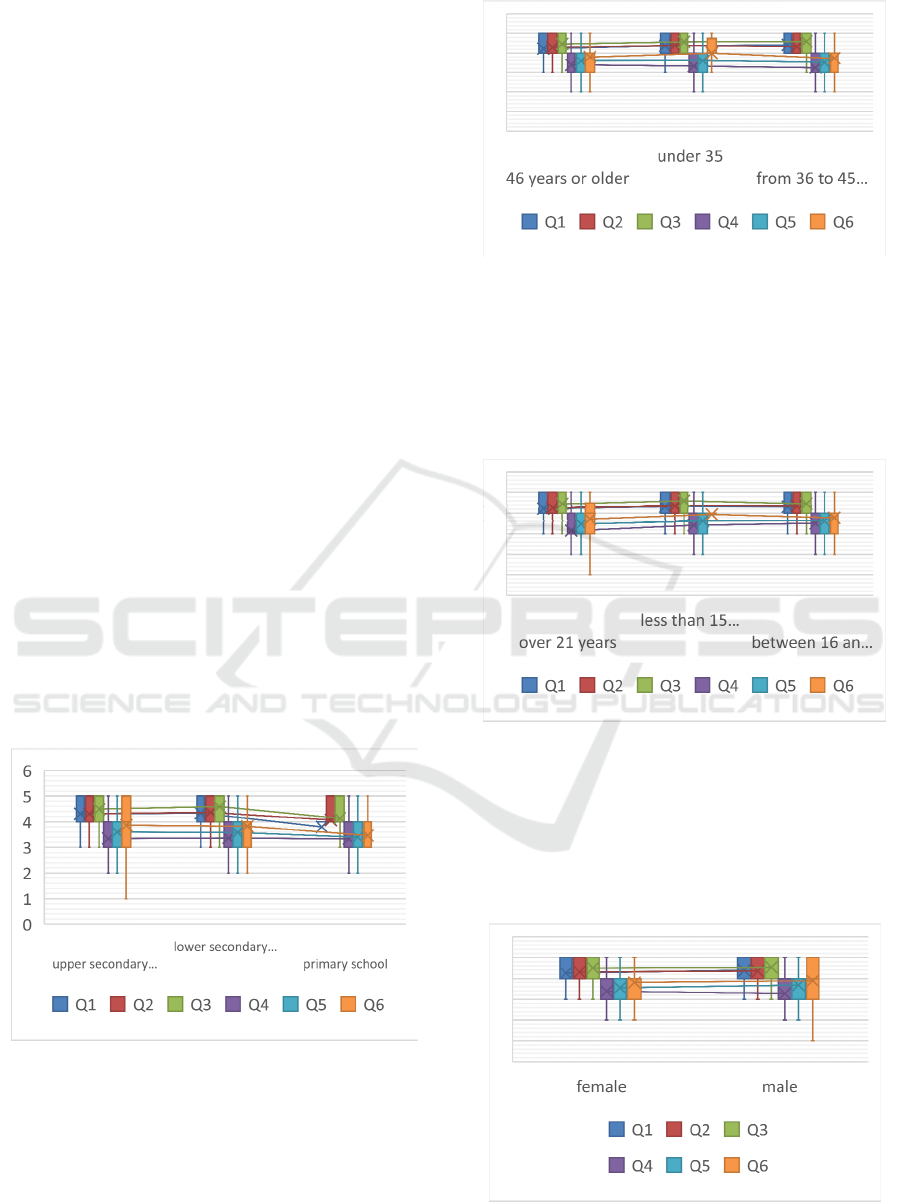

This research also aims at investigating how

responses to the questions in Table 1 were affected by

various parameters. For instance, when considering the

order of the school in which teachers worked, Figure 7

illustrates that, on average, primary school teachers

gave lower responses to all questions. This could be

attributed to the difficulty of introducing and using AI-

related concepts at a lower level of schooling. This

trend was observed across all questions.

Figure 7: Answers to questions of Table 1 divided by order

of school.

Considering the age of the teacher (Figure 8), the

trend is similar for all questions across all three age

groups, with a slight difference for Q6. Younger

teachers appear to agree more on the fact that

designing teaching activities to prepare for AI is

necessary.

Figure 8: Answers to questions of Table 1 divided by age

of teachers.

Regarding years of teaching (Figure 9), the

answers do not differ among the groups considered.

Based on the average trends, it can be concluded that

teachers with fewer years of service are the category

that most agrees with the statements in Table 1.

Figure 9: Answers to questions of Table 1 divided by levels

of years of teaching.

The investigation into gender differences did not

yield significant results (Figure 10). However, it

should be noted that the number of female teachers

who responded is approximately three times higher

than that of male teachers.

Figure 10: Answers to questions of Table 1 divided by

gender of teachers.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

124

5 DISCUSSION

The increasingly widespread use of AI across various

sectors is a notable trend globally. AI technologies are

being adopted in diverse fields, including education.

The paper presents teachers' perspectives on AI in

terms of their knowledge, use, and interest in

receiving training on AI in the education field. The

results from a survey proposed to 255 Italian teachers

of all levels and disciplines from October 2023 to

January 2024 managed to identify important

considerations and needs of teachers. The results

show the level of diffusion and the teachers'

perspective on the use of AI in Italian schools.

The sample of respondents is largely made up of

elderly teachers, some of whom may be at the end of

their careers, and one might expect them to be less

inclined to use innovative tools; instead, a high

propensity to learn about and use AI tools for teaching

purposes was found. Some teachers (34.1%) have

already attended AI training courses, but few of them

frequently employ AI for personal use in their daily

lives (14.8%). The low confidence in their skills and

knowledge of AI emerged. This is probably due to a

lack of previous steps, i.e. general knowledge about

AI, how it works and its aspects and characteristics,

in fact, teachers strongly agree with the statement

related to their needs to learn to use, know and

recognise AI and its ethics and where it intervenes in

everyday life. Their insecurity could be due to the fact

that the schools where they teach (96.1% of the

schools of the respondents) do not follow specific

policies on the use of AI and only 11.4% of

respondents state that the school where they work

encourages the use of AI-based applications in the

classroom. Accordingly, if teachers are unsure of

their AI skills, they are reluctant to use AI not only

for personal use, but also for educational purposes.

Teachers' confidence in their knowledge of AI

applications in education is very low, as highlighted

in the results. Integrating AI into education requires

not only technological literacy but also an

understanding of how to effectively leverage AI tools

to enhance the learning experience. In this sense, an

important synergy between education, research, and

teacher training is necessary to meet the educational

and training needs of the constantly evolving

technological field. As emphasised by Gocen and

Aydemir (2020), in order to implement strategic and

targeted interventions, it is necessary to know what

teachers need and how they work to create solutions

that are sustainable in real-world settings. It is

precisely from this perspective that the survey has

been formulated precisely to test the waters of Italian

teachers and to be able to act with targeted

interventions to accompany teachers in this delicate

transition. The fact that teachers are not too afraid of

the massive proliferation of AI in various fields is a

hopeful sign, suggesting that they are willing to learn

new tools and keep up with technological

developments. As highlighted in the results, the

majority of teachers said they strongly need training

in AI, which is another sign of the current willingness

and readiness of teachers to learn and integrate new

AI tools into education. The urgent need of training

programs for teachers was also suggested in (Lo,

2023) and it is probably also dictated by the large gap

between the ease of use of AI-based tools and the

difficulty teachers have in explaining the mechanisms

and technologies behind them (Fissore et al., in

press).

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study provides an overview of Italian teachers'

attitudes towards AI-related topics and an overview

of the use of AI in Italian schools. The findings

suggest a need for teacher training to prepare them for

AI, including its integration into daily life and the

associated ethical issues. At the European level, there

are many initiatives to define guidelines for the use of

AI in education, to guide schools, teachers, and

students in the conscious use of AI.

To answer the first research question "How

confident are Italian teachers about AI?” even though

about 1/3 of the teachers interviewed have attended a

training course on AI, it is possible to state that they

are not yet confident in their knowledge of the topics.

As a consequence, even if teachers agree that it is

important for students to learn about and recognise AI

and where it is intervening in everyday life, a large

proportion of them do not include AI tools in their

teaching or introduce students to AI technologies.

To answer the second research question “How

much do Italian teachers use AI in education?” up to

now it is possible to state that AI is slowly making its

way into didactics of Italian teachers. It might depend

on the fact that teachers still do not know how to deal

with AI technologies. It could also depend on the fact

that teachers still do not know how to move into AI

technologies, so it is necessary to train them to deepen

these new realities and tools and to integrate them into

education. In this moment it is important to support

teachers through this important change and guide

them to use AI tools without seeing them as a threat

but rather as a resource to enhance the learning

process.

From Theory to Training: Exploring Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence in Education

125

Thus, in response to the third research question,

"How interested are Italian teachers in training on AI

in education?", it is not only possible to state that the

majority of teachers are interested in training on AI,

because it is not just a question of interest, but there

is an urgent need at the moment to know and to be

able to use new AI technologies.

We are aware that the sample of teachers is

limited to STEM teachers mainly in upper secondary

education. This was a first step of scanning teachers’

attitude towards AI aimed at fostering a reasoned and

purpose−driven use of AI in educational practice.

In the future, we hope that Italian schools will also

play their part in facilitating the use of innovative

tools such as AI by introducing guidelines, also

defined by institutional reference frameworks, that

could guide them in this transition and also facilitate

teachers' work.

Additionally, we aim to understand how students

at different levels of education perceive the world of

AI. The goal will be to understand how students

interact with new and emerging tools in the field of

AI, how consciously they use them both in

educational settings and in everyday life, and how

much they understand about the mechanisms behind

using AI-based tools.

The impact of AI on education and research is

significant and will continue to evolve and

increasingly change the way we teach, learn, and

research. To explore the implications of AI in

education, the world of education and research must

work together.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was carried out within Indam - Istituto

Nazionale di Alta Matematica "Francesco Severi"

and the national PP&S - Problem Posing and Solving

Project.

REFERENCES

Balacheff, N. (1993). Artificial intelligence and

mathematics education: Expectations and questions. In

14th Biennal of the Australian Association of

Mathematics Teachers (pp. 1-24). Curtin University.

Barana, A., Fissore, C., & Marchisio, M. (2020, May).

Automatic Formative Assessment Strategies for the

Adaptive Teaching of Mathematics. In International

Conference on Computer Supported Education (pp.

341-365). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Barana, A., Marchisio, M., & Roman, F. (2023). Fostering

problem solving and critical thinking in Mathematics

through generative artificial intelligence. In The 20th

international conference on Cognition and Exploratory

Learning in the Digital Age (CELDA 2023) (pp. 377-

385). IADIS press.

Chassignol, M., Khoroshavin, A., Klimova, A., &

Bilyatdinova, A. (2018). Artificial Intelligence trends in

education: a narrative overview. Procedia Computer

Science, 136, 16-24.

Chen, L., Chen, P., & Lin, Z. (2020). Artificial intelligence

in education: A review. Ieee Access, 8, 75264-75278.

COMEST (World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific

Knowledge and Technology). (2019). Preliminary

study on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence.

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367823

(last access 26 January 2024).

Dignum, V., Penagos, M., Pigmans, K., VoslooPolicy, S.

(2021). Guidance on AI for children (Version 2.0):

Recommendations for building AI policies and systems

that uphold child rights. United Nations Children's

Fund (UNICEF).

EC Communication from the Commission to the European

Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the

European Economic and Social Committee and the

Committee of the Regions. Artificial Intelligence for

Europe. COM(2018) 237 final {SWD(2018) 137 final}.

Fissore, C., Floris, F., Marchisio, M., & Rabellino, S.

(2023a). Learning analytics to monitor and predict

student learning processes in problem solving activities

during an online training. In 2023 IEEE 47th Annual

Computers, Software, and Applications Conference

(COMPSAC) (pp. 481-489). IEEE.

Fissore, C., Fradiante, V., Marchisio, M., Pardini, C.

(2023b). Design didactic activities using gamification:

the perspective of teachers. In: Nunes, M. B., Isaías, P.,

Issa, T., Issa, T. (eds.) Proceedings of E-Learning and

Digital Learning (pp. 11–18). IADIS Press, Porto.

Fissore, C., Floris, F., Marchisio, M., & Sacchet, M. (2022).

Didactic activities on Artificial Intelligence: the

perspective of STEM teachers. In Proceedings of the

19th international conference on Cognition and

Exploratory Learning in the Digital Age (CELDA 2022)

(pp. 11-18). IADIS press.

Fissore, C., Floris, F., Marchisio Conte, M., Sacchet, M. (in

press). Teacher training on artificial intelligence in

education.

Floris, F., Marchisio, M., Rabellino, S., Roman, F., &

Sacchet, M. (2022). Clustering Techniques to

investigate Engagement and Performance in Online

Mathematics Courses. In Proceedings of the 19th

international conference on Cognition and Exploratory

Learning in the Digital Age (CELDA 2022) (pp. 27-34).

IADIS press.

Gocen, A., & Aydemir, F. (2020). Artificial Intelligence in

Education and Schools. Research on Education and

Media, 12(1), pp. 13-21.

Kahraman, H. T., Sagiroglu, S., & Colak, I. (2010).

Development of adaptive and intelligent web-based

educational systems. In 2010 4th international

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

126

conference on application of information and

communication technologies (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

Holmes, W., Anastopoulou, S., Schaumburg, H., Mavrikis,

M. (2018). Technologyenhanced Personalised

Learning: Untangling the Evidence. Robert Bosch

Stiftung GmbH, Stuttgart.

Holmes, Wayne; Bialik, Maya; Fadel, Charles; (2023)

Artificial intelligence in education. In: Data ethics :

building trust : how digital technologies can serve

humanity. (pp. 621-653). Globethics Publications.

Lo, C.K. (2023). What Is the Impact of ChatGPT on

Education? A Rapid Review of the Literature. Educ.

Sci., 13, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040410

Luckin, R., & Holmes, W. (2016). Intelligence unleashed:

An argument for AI in education. Pearson.

Miao, F., Holmes, W., Huang, R., & Zhang, H. (2021). AI

and education: A guidance for policymakers. UNESCO

Publishing.

Ministry for Economic Development (2020), Proposte per

una Strategia italiana per l'intelligenza artificiale,

Elaborata dal Gruppo di Esperti MISE sull’intelligenza

artificiale. Retrieved from https://www.mise.gov.it/

images/stories/documenti/Proposte_per_una_Strategia

_italiana_AI.pdf, last accessed July 25th, 2022.

OECD. (2023). Education at a Glance 2023: OECD

Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris, (https://doi.org/

10.1787/e13bef63-en)

Ouyang, F., & Jiao, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence in

education: The three paradigms. Computers and

Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100020.

Pedro, F., Subosa, M., Rivas, A., & Valverde, P. (2019).

Artificial intelligence in education: Challenges and

opportunities for sustainable development, Education

2030, UNESCO (https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48

223/pf0000366994)

Samoili, S., Cobo, M. L., Gómez, E., De Prato, G.,

Martínez-Plumed, F., & Delipetrev, B. (2020). AI

Watch. Defining Artificial Intelligence. Towards an

operational definition and taxonomy of artificial

intelligence. EUR 30117 EN, Publications Office of the

European Union, Luxembourg, ISBN 978-92-76-

17045-7, doi:10.2760/382730, JRC118163.

Zhong, Y. X. (2006, July). A cognitive approach to artificial

intelligence research. In 2006 5th IEEE International

Conference on Cognitive Informatics (Vol. 1, pp. 90-

100). IEEE.

From Theory to Training: Exploring Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence in Education

127