Measuring Older People’s Attitudes Towards Personal Robots

Helen Petrie

1a

and Sanjit Samaddar

2b

1

Department of Computer Science, University of York, York YO105DD, U.K.

2

School of Arts and Creative Technologies, University of York, York YO105DD, U.K.

Keywords: Older People, Personal Robots, Attitudes, Measurement.

Abstract: Robotic technologies are increasingly an important form of technology to support older people. It is important

to have easy ways of measuring their attitudes to the kinds of robots which might support them. A study was

conducted with 249 older people in the UK who viewed videos of three different types of robots (abstract, pet

and humanoid) and rated their attitudes to each using an adaptation of the Almere model questionnaire.

Analysis of the Almere Questionnaire revealed three underlying components to attitudes to the personal

robots: Positive User Experience; Anxiety and Negative Usability; and Social Presence. There were

significant differences between the three personal robots in older people’s attitudes to them, with the pet robot

having the most positive attitudes. These results are a set towards creating simple methods for developing a

clear understanding of older people’s attitudes to personal robots which may be useful in helping them choose

appropriate robots to support themselves. The results make a contribution to understanding the attitudes of

older people in the UK to three types of personal robot that they may find useful and companionable.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is well known that the world’s population is ageing,

particularly in more developed parts of the world. The

United Nations (UN, 2022) estimates that in 2020

there approximately 6% of the world population was

aged 65 or over (a widely used, if rather coarse,

criterion for “older people”). By 2050 it is estimated

that number will increase to approximately 16.0% of

the population, nearly a three-fold increase in

percentage terms. However, what is perhaps more

important than the raw numbers or percentages of

older people, is the Potential Support Ratio (PSR).

This is the ratio of the number of people of working

age (i.e. those who produce most of the wealth and

value in a society and who are also available as the

main carers for older people who need support) to the

number of older people. Europe currently has a PSR

of approximately four younger people for each older

person, although many European countries have a

PSR of less than three younger people to each older

person, and Japan has the lowest ratio in the world at

just over two younger people to each older person

(UN, 2019).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0100-9846

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0332-3561

Digital technologies are often seen as a major part

of the solution to this problem (Petrie & Darzentas,

2020), with the concept of ambient/active assisted

living (AAL) emerging as early as the 1970s

(Monekosso et al., 2015) to describe “the use of

information and communication technologies in

people’s daily living and working environment to

enable them to stay active longer, remain socially

connected, and live independently into old age”

(AAL Association, n.d.). This also aligns with the

“aging in place” concept (Mynatt et al., 2000), as

most older people wish to live independently in their

own homes for as long as possible. Since the

COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting social

isolation measures, there is a particular relevance and

motivation to understand the technological support

that can be provided to older people and find solutions

to combat lowering PSR ratios globally.

There has been extensive research and

development of robotic technologies. An important

part of this research is assistance provided by robotic

technologies to provide care and support for older

people. These can range from physical care such as

encouraging activity (e.g., El Kamali et al., 2018) or

108

Petrie, H. and Samaddar, S.

Measuring Older People’s Attitudes Towards Personal Robots.

DOI: 10.5220/0012740400003699

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2024), pages 108-118

ISBN: 978-989-758-700-9; ISSN: 2184-4984

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

intelligent mobility aids (e.g., López Recio et al.,

2013) to more social care such as mediating

communication and providing companionship (Feil-

Siefer & Matarić, 2011).

Robots to support older people can come in many

shapes and sizes ranging from abstract robots such as

Afobot (Fig. 1A) to pet robots such as Miro (Fig. 1B).

and humanoid robots such as Sanbot (see Fig. 1C).

With the range of functionalities and types available,

robots may be perceived as intimidating (Frennert,

2020), not useful for general day-to-day care

(Samaddar & Petrie, 2020), or not designed with the

needs of older people in mind (Eftring & Frennert,

2016). Care needs to be taken in the development of

robot technologies for older people to ensure that they

are acceptable to the varied target audience of older

people. Therefore, it is important to have instruments

to easily measure older people’s attitudes to robot

technologies.

Some research has been undertaken to measure

older people’s attitudes to robots. A widely used

measure is the Almere model (Heerink et al., 2010)

which provides a questionnaire which measures the

attitudes to “assistive social agents” by older people.

This was developed from the theoretical constructs of

the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) developed

in the 1980s about technology in general (Davis,

1989) and was tested with Dutch older people mainly

using one small pet robot, the iCat. Other measures

have also been developed to measure attitudes to

robots by users of any age (Bartneck et al; 2009;

Nomura et al, 2008; Smarr et al, 2012). All these

measures are now over a decade old, and the

components of attitudes to robots may have changed

in that time, as there has been much more exposure to

robotic technology.

The aim of this research is to extend the work of

Heerink and colleagues in order to develop a more up-

to-date questionnaire to easily measure the attitudes

of older people to robots. We developed this

questionnaire by asking older people to react to a

range of different types that might support them:

abstract, pet and humanoid robots. We worked with a

large sample of UK older people, to complement the

Dutch participants who participated in the

development of the Almere questionnaire. We

investigated whether the theoretical constructs of the

TAM model were appropriate in this situation. This

is a first step towards a more robust questionnaire for

measuring older people’s attitudes to the robotic

technologies which might be developed to support

them.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Terminology for Robots for Older

People

Thus far we have used the term “robot” to refer to any

robotic technology to support older people. There is

no universally accepted or preferred term for the wide

range of robotic technologies being developed in this

area. The term “robot” has been used as an umbrella

term, with a description of the functionality preceding

the basic word, often “social robot” or “assistive

robot”. Petrie et al. (2018) found there were nearly 30

terms used in relation to robot technologies for older

people. While they suggested a classification of

robots, both physical and virtual, we propose a more

general term to refer to the technologies discussed in

this paper: “personal robot”. This term allows us to

refer to all the different types of robots and robot-like

devices now available, while not focusing particularly

on their type or use. In addition, we feel this term

provides a less stigmatizing term than “assistive

robot” and a more accessible term for a general

audience not familiar with the nuances and

differences between terms such as robot, agent, social

agent etc.

2.2 Personal Robots for Older People

Research on personal robots for older people has

mostly focused on three areas of care: physical

healthcare, supporting declining cognitive

capabilities, and social interaction and

companionship. Healthcare is by far the most

researched and developed area with robots used in a

variety of ways: to help with physical tasks

(Hebesberger et al., 2016), health monitoring

(Rosales et al., 2017), smart walkers (Sinn & Poupart,

2011), and fall detection (Mundher & Zhong, 2014).

To support and aid with cognitive decline and

provide coaching in this area there are robots that

have been designed to act as coaches for both physical

and cognitive tasks. One example is a robot that

provides mental games and tasks for a user to do and

tailors the games to suit the user’s level of cognitive

ability (Agrigoroaie & Tapus, 2016). Other robots

combine both entertainment and cognitive

stimulation by providing games such as bingo (Li et

al., 2016) or a card matching memory game (Khosla

& Chu, 2013). Lastly, there is an abundance of

research into pet robots and other robots that provide

a means of social interaction and which aim to combat

loneliness for older people. Pet robots provide

companionship like a real pet but are sometimes more

Measuring Older People’s Attitudes Towards Personal Robots

109

suited for older people who may not be capable of

taking care of a real pet’s needs. The most well-

known is probably Paro (Wada & Shibata, 2007), a

small, furry baby seal robot that reacts to touch. Paro

has had a significant positive influence on older

people’s lives at care homes. Following this

innovation, there has been much research into pet

robots including other animals as diverse as koalas,

penguins, and dogs (Lazar et al., 2016).

2.3 Measuring Older People’s

Attitudes to Personal Robots

Heerink et al. (2008, 2009, 2010) investigated the

attitudes to “assistive social agents” by older people,

and developed the Almere model and questionnaire.

The Almere questionnaire includes 41 items divided

into 12 different constructs derived from TAM (see

Table 1). Different parts of the model were validated

in four experiments with older people and several

social robots. We argue that while the model and

results are strong, the model was created on the

theoretical model of the TAM rather than empirical

work with older people and therefore would benefit

from further validation with data from a large sample

of older people, as it is not clear that these constructs

are both sufficient and necessary. In addition, there

have been many studies that have adapted the Almere

model, selecting only specific constructs that apply,

to measure or predict acceptance. For example,

removing the social constructs if the robot’s core

functionality is not social in nature (e.g.,

Karunarathne et al., 2019). But taking always small

parts of a questionnaire can be a threat to the validity

of the instrument. These points all provide motivation

to extend Heerink et al’s work to see if a more general

model can be developed for understanding older

people’s attitudes towards personal robots.

In this paper we will build on the work by Heerink

and colleagues on their Almere model by

investigating the reactions of a large sample of older

people in the UK with three types of personal robots.

This will allow us to investigate the underlying

structure of their attitudes to personal robots based

directly on their data. It should also allow us to

conduct a preliminary investigation of similarities

and differences between their attitudes to the three

different types of personal robots used in the study:

abstract, pet and humanoid. We will investigate two

research questions:

RQ1: Are the Almere model constructs

appropriate to describe UK older people’s attitudes to

three types of personal robots?

RQ2: How do attitudes to the three robots differ

on the most appropriate set of constructs?

Table 1: Almere model constructs (source: Heerink et al.,

2010).

Construct Definition

Anxiety Evoking anxious or emotional

reactions when using the system

Attitude Positive or negative feelings about the

appliance of the technology

Facilitating

Conditions

Objective factors in the environment

that facilitate using the system

Intention to

Use

The outspoken intention to use the

system over a longer period of time

Perceived

Adaptability

The perceived ability of the system to

be adaptive to the changing needs of

the user

Perceived

Enjoyment

Feelings of joy or pleasure associated

by the user with the use of the system

Perceived

Ease of Use

The degree to which the user believes

that using the system would be free of

effort

Perceived

Sociability

The perceived ability of the system to

perform sociable behaviour

Perceived

Usefulness

The degree to which a person believes

that using the system would enhance

his or her daily activities

Social

Influence

The user’s perception of how people

who are important to him/her think

about him/her using the system

Social

Presence

The experience of sensing a social

entity when interacting with the system

Trust The belief that the system performs

with personal integrity and reliability

3 METHOD

3.1 Design

A within-participants online study was conducted. To

investigate older adults’ initial understanding of the

idea of a “personal robot”, participants were initially

asked to describe what the term meant to them in an

open-ended question. To assess older people’s

attitudes to personal robots, participants watched one-

minute videos of three robot types (abstract: Afobot;

pet: MiRo; humanoid: Sanbot; see Figure 1), each

video contained several examples of the robot type

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

110

Figure 1: The three personal robots (A: Afobot; B: MiRo; C: Sanbot).

and a range of functions they could perform to assist

older people to live independently at home. A large

sample of participants was required for the validation

planned, so it was not possible to have each

participant actually interact with each robot. In

addition, this research was conducted at the end of the

coronavirus pandemic, when there was a possibility

that social isolation regulations might be re-imposed

which would prohibit in-person research, particularly

with older participants.

After each video participants were asked two

attention check questions to make sure they had

watched the video (these asked for factual

information about the video) and then completed a set

of questions based on the Almere questionnaire. The

order of presentation of the three videos and the order

of the items within the questionnaire were

counterbalanced to avoid practice and fatigue effects.

Ethical approval for the study was given by the

Physical Sciences Ethics Committee of the University

of York.

3.2 Participants

Inclusion criteria were to be 60 years or older, to be

living in the United Kingdom and living

independently (rather than in sheltered

accommodation or a care facility). Participants were

recruited via announcements of a variety of channels:

a local community website, the University of York

news bulletin and Slack channel, and the Prolific

research participant website (prolific.co).

Participants recruited via Prolific were offered GBP

2.00 (approximately USD 2.47, 2.28 euros) for their

time, for the other participants, the researchers paid

GBP 2.00 to the Disasters Emergency Committee

(dec.co.uk) to support work with people in

Afghanistan and the Ukraine.

261 people were recruited and completed the

online study. However, 12 (4.6%) participants

answered more than half the attention check questions

incorrectly, so their data was removed, leaving 249

participants.

Demographic information about the participants

is summarized in Table 2. 153 (61.4%) participants

were in their 60s, 89 (35.7%) were in their 70s and 7

(2.8%) were in their 80s. There was a good gender

balance and a good range of educational

backgrounds. Participants were asked their current or

last occupation and there was a wide range from

builder and bus driver to IT project manager and

biomedical scientist.

Table 2: Demographic information for the participants.

Age Range: 60 - 87 years

Median: 68 years

Gender Women: 134 (53.8%)

Men: 115 (46.2%)

Other 0 (0.0%)

Education High School: 107 (43.0%)

Bachelor degree: 75 (30.1%)

Higher degree: 33 (13.3%)

Professional qualification: 34 (13.7%)

Employment Full-time/Self Employed: 25 (10.0%)

Part-time/Self Employed: 31 (12.4%)

Retired: 193 (77.5%)

Participants were asked to rate their confidence

with computers and with using the Internet on 7-point

Likert items (not at all confident = 1 to very confident

= 7). The median rating for confidence with

computers was 6.0 (semi-interquartile rating (SIQR):

0.5), which was significantly above the midpoint of

Measuring Older People’s Attitudes Towards Personal Robots

111

the scale (Wilcoxon one sample signed rank test T =

11.16, p < .001). The median rating for confidence

with the Internet was also 6.0 (SIQR: 0.05), also

significantly above the midpoint of the scale

(Wilcoxon T = 13.17, p < .001).

Participants were asked whether they had any

experience of personal robots, 39 (15.7%) reported

that they had. The most frequently mentioned type

was robotic vacuum cleaners (mentioned by 32

participants); virtual assistants (e.g., Alexa, Siri) were

mentioned as robots by 9 participants; robotic lawn

mowers (4 participants); industrial/manufacturing

robots (2 participants); information robots at airports,

robotic mops, robotic swimming pool cleaners,

robotic turtles for education were all mentioned by

one participant each.

3.3 Materials

The online study was deployed using the Qualtrics

online survey tool (www.qualtrics.com). The study

comprised three sections:

1. Information page, informed consent

2. Robot videos and Almere Questionnaire

3. Demographic information and thanks.

1. Information page, informed consent: the study

opened with an information screen about what would

be involved in participating in the study, information

about confidentiality and anonymity and how to

withdraw from the study if wished. An informed

consent form then followed.

2. Videos of personal robots and Almere

Questionnaire

Participants were shown three videos of different

types of personal robot (abstract, pet and humanoid,

those illustrated in Figure 1), each video was

approximately one minute long (videos available

from the authors). Each video comprised publicly

available footage of the robot and showed a number

of functions typical of that robot. To orient the

participants, each video was preceded by a short text

introduction to the robot type. These introductions

were all approximately 75 words long and with the

same amount of information (see Table 3).

Each video was followed by two multiple choice

attention check questions which asked for specific

concrete details of the video content, to enable us to

check that participants had watched the video

carefully. Participants then completed a 39 item

questionnaire adapted from the Almere questionnaire

(Heerink et al., 2010). Our questionnaire was two

items shorter than the original Almere questionnaire

(which comprised 42 items), as the original

questionnaire included three statements about

intention to use the robot in the next few days. As this

was not a possibility for participants in this study,

these statements were replaced by one statement “I

would use the [name] robot if offered one”.

The questionnaire consisted of 39 statements

about the robot on a 7-point rating scale from

Strongly Disagree (coded as 1) to Strongly Agree

(coded as 7). Heerink and colleagues asked older

people to rate these statements after they had

interacted with a robot for a short period of time (e.g.,

I think the [name] robot is useful to me), whereas in

this study participants had only seen the robot in the

video, so the formulation of the statements was

changed to the hypothetical form (e.g., I think the

[name] robot would be useful to me). This resulted

in only minor changes to the wording of the

statements in the Almere questionnaire.

3. Demographic information and thanks

Participants were asked demographic questions and

thanked for their participation in the study.

Table 3: Text introductions to the three personal robot

videos.

Afobot is a tabletop personal robot. It has a screen

that will rotate towards you when you speak to it and

will understand your voice commands (like Alexa

and Siri). It can assist in a range of activities of daily

life such as reminding you of appointments or taking

your medicines. It can quickly connect you to your

family and friends via voice or video calls and can

take and send photos for you.

MiRo is a pet-like personal robot. It can move

around independently, but will also be attracted by

human movement and sounds. You can train it to

respond to particular actions like clapping your

hands as you might a pet. It also responds to being

stroked by moving its head, ears, and tail and

changing colour. It also makes animal-like sounds. It

can show different emotions with these features and

goes to "sleep" automatically to recharge itself.

Sanbot is a human-like personal robot with a head

and arms and a screen. It can move around

independently and can recognise different people

using face recognition. It will also understand voice

commands. It can assist in a range of activities of

daily life such as reminding you of appointments or

taking your medicines. It can quickly connect you to

your family and friends via voice or video calls and

monitor your health by linking with a smartwatch.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

112

4 RESULTS

To investigate RQ1(Are the Almere model constructs

appropriate to describe older people’s attitudes to

three types of personal robots?), we first investigated

whether the rating for each of the attitude statements

within each Almere construct were consistent with

each other. Cronbach’s alpha, a measure of internal

consistency, was calculated for each construct, but

separately for each robot type. A Cronbach’s alpha of

at least 0.80 is considered adequate consistency for

this kind of data (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Table 4 presents the Cronbach’s alpha results for

the 11 Almere constructs we measured with more

than one statement (as noted above, Intention to Use

was measured by only one statement). It is interesting

that the consistency measure is very similar across the

three robots for most of the constructs; only on

Perceived Ease of Use and Social Presence was it

very different. However, a number of the constructs

failed to reach an adequate level of consistency for

any of the three robots: Facilitating Conditions,

Perceived Adaptability, and Perceived Ease of Use.

Social Influence and Social Presence failed to reach

consistency for MiRo, and Anxiety just failed to reach

consistency for both Afobot and MiRo. Only on six

of the 11 constructs was consistency reached for all

three robots (we will include Anxiety as consistent, as

this was marginal). Thus, the statements in the

Almere questionnaire, for these participants and these

robots, do not always provide consistent measures of

the constructs they are designed to measure.

Therefore, to investigate whether there is an

alternative to the Almere constructs, that is a

statistically reliable set of underlying meaningful

constructs in older participants’ attitudes to the

personal robots, a Principal Components Analysis

(PCA) was conducted on the Almere Questionnaire

responses, again for each personal robot separately

(see Table 5).

For Afobot and Sanbot, three componennts

3

produced the most appropriate solutions (in terms of

proportion of variance accounted for and semantic

grouping of items): for Afobot 62.1% of the variance

in responses was accounted for, and for Sanbot

64.7%. These are very adequate proportions of the

variance accounted for.

3

We will use component to refer to the results of the

PCA to avoid confusion with the theoretically derived

constructs in the Almere questionnaire.

Table 4: Cronbach’s alpha for each of the Almere model

constructs for each personal robot.

Afobot MiRo Sanbot

Anxiety 0.79 0.79 0.81

Attitude 0.91 0.91 0.91

Facilitating

Conditions

0.75 0.70 0.75

Perceived

Adaptability

0.59 0.62 0.53

Perceived

Enjoyment

0.92 0.94 0.94

Perceived Ease

of Use

0.60 0.33 0.75

Perceived

Sociability

0.88 0.87 0.88

Perceived

Usefulness

0.89 0.90 0.92

Social Influence 0.80 0.77 0.82

Social Presence 0.86 0.63 0.90

Trust 0.91 0.90 0.90

The three components can be summarized as:

Positive User Experience (PUX): includes the

usefulness and adaptability of the robot, as well as the

pleasure of interacting with the robot.

Anxiety and Negative Usability (AnxNegU):

includes anxieties about knowing how to interact

with the robot, and usability issues, but in a negative

sense (i.e. that it would be difficult to learn to use and

the person would need help)

Social Presence (SocPres): the sense that the robot

is a living, sentient being.

For MiRo, two components produced the most

appropriate solution, accounting for 56.4% of the

variance. However, the components were very similar

to those of the other two robots, the difference being

that the SocPres items grouped with the PUX items

rather than creating a separate component.

Thus, there are meaningful groupings of the

attitudes statements, based on the participants own

ratings, which are meaningful and create a simpler

model for studying attitudes to personal robots for

older people than the complex set of contstructs

proposed by TAM.

Measuring Older People’s Attitudes Towards Personal Robots

113

Table 5: Components extracted from PCAs on responses to Almere Questionnaire for each personal robot.

Afobot MiRo Sanbot

Positive User Experience (PUX)

I think it would be a

g

ood idea to use the [X] robo

t

xx x

The [X] robot would make life more interestin

g

xx x

It would be

g

ood to make use of the [X] robo

t

xx x

I would use the [X] robot if offered one x x x

I think the [X] robot would be adaptive to what I nee

d

xx x

I think the [X] robot would only do what I need at that particular

momen

t

x x x

I think the [X] robot would help me when I considered it to be

necessar

y

x x x

I would en

j

o

y

the [X] robot talkin

g

to me x x x

I would en

j

o

y

doin

g

thin

g

s with the [X] robo

t

xx x

I would find the [X] robot en

j

o

y

able x x x

I would find the [X] robot fascinatin

g

xx x

I would find the [X] robot borin

g

[reversed] x x x

I would think the [X] robot would be nice x x x

I think the [X] robot would be useful to me x x x

It would be convenient for me to have the [X] robo

t

xx x

I think the [X] robot would help me with man

y

thin

g

sxx x

I think m

y

famil

y

and friends would like me usin

g

the [X] robo

t

xx x

I think it would

g

ive a

g

ood impression if I were to use the [X] robo

t

xx x

I would find the [X] robot pleasant to interact with x x

When interacting with the [X] robot I would feel like I’m talking to a

real bein

g

x

It would feel as if the [X] robot is reall

y

lookin

g

at me x

I could ima

g

ine the [X] robot to be a livin

g

creature x

I would think the [X] robot is a real bein

g

x

The [X] robot would seem to have real feelin

g

sx

I would consider the [X] robot a pleasant conversational partne

r

x

I would feel the [X] robot would understand me x

Anxiety-Negative Usability (Anx-NegU)

If I were to use the [X] robot, I would be afraid to make mistakes with

it

x x x

If I were to use the [X] robot, I would be afraid to break somethin

g

xx x

I would find the [X] robot intimidatin

g

xx

I have ever

y

thin

g

I would need to use the [X] robot (R) x x x

I know enough about the [X] robot to be able to make good use of it

(R)

x

I think I would know quickl

y

how to use the [X] robot (R) x x x

I would find the [X] robot eas

y

to use (R) x x x

I think I would be able to use the [X] robot without an

y

help (R) x x x

Social Presence (SocPres)

When interacting with the [X] robot I would feel like I’m talking to a

real bein

g

x x

I could ima

g

ine the [X] robot to be a livin

g

creature x x

I would think the [X] robot is a real bein

g

x x

The [X] robot would seem to have real feelin

g

sx x

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

114

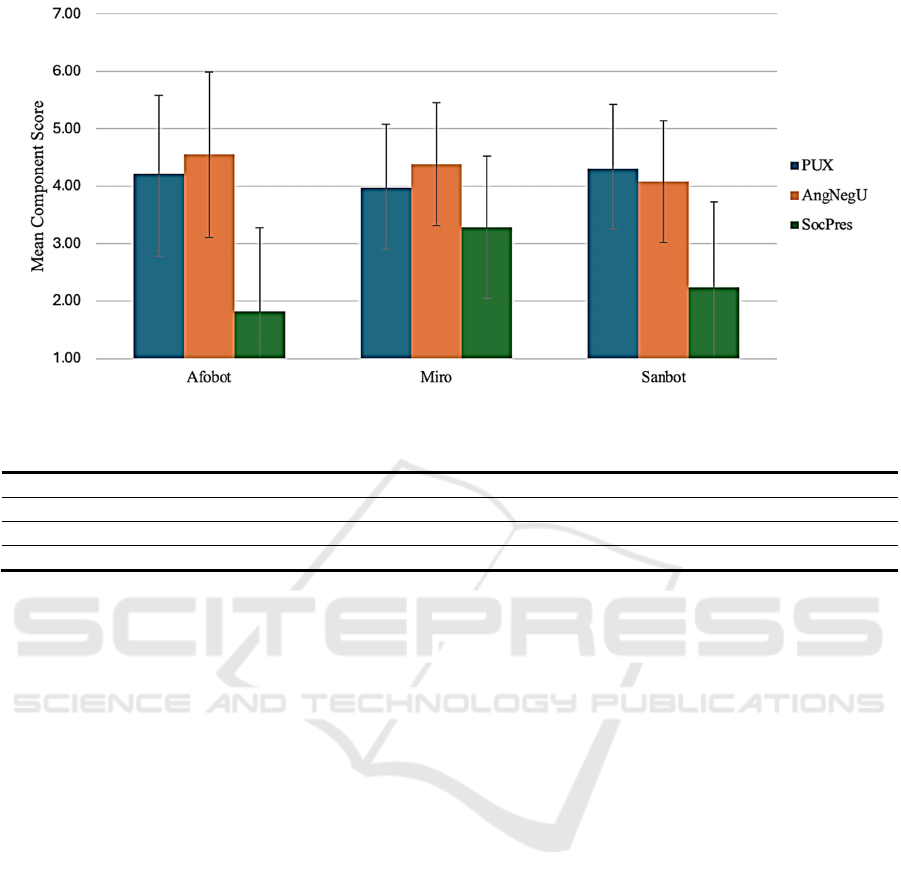

Figure 2: New Almere-derived component scores for the three personal robots.

Table 6: Summary of repeated measures ANOVA on the new components for the three robots.

Source F value df p value Effect size (ηp

2

)

Robot t

y

pe 39.15 1.99, 492.70 < 0.001 0.136

Almere componen

t

317.35 1.68, 415.75 < 0.001 0.561

Robot x Almere 189.06 3.78, 937.15 < 0.001 0.433

To investigate RQ2 (How do attitudes to the three

robots differ on the most appropriate set of

constructs?), participants’ scores on the proposed

three component structure of the Almere items was

calculated for all three robots (although this was not

the best solution for MiRo, the three component

model was used for this robot to allow comparison

with the other two) with the AnxNegU component

ratings reversed, so that a high rating always indicates

a positive attitude (in the case of AnxNegU, not being

anxious or knowing how to interact with the robot).

Fig. 2 illustrates the mean component ratings.

A repeated measures analysis of variance

(ANOVA) was then conducted on the component

ratings for the three robots. The results are

summarized in Table 6. Overall, there was a

significant difference with a large effect size between

the three robots. MiRo had the most positive ratings,

post hoc analysis showed this was significantly higher

than either Afobot or Sanbot which did not differ

significantly from each other. There was also a

significant difference between the three components.

PUX and AnxNegU had significantly higher ratings

than SocPres. There was also a significant interaction

between robot and component. As can be seen from

Fig. 2, this was largely caused by SocPres being much

higher for MiRo than the other two robots.

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated how to measure the attitudes

of older people to a range of personal robots, using a

large sample of older people in the UK and three

different personal robot types. The study had the dual

aims of moving towards a robust measure for

measuring such attitudes and conducting a

preliminary investigation into the attitudes of older

people to three different types of personal robots. The

research built on and extended the work by Heerink

and colleagues on their Almere model.

The first analysis investigated whether the

constructs in the Almere model, which were derived

theoretically from the TAM model of technology

acceptance (Davis, 1989) would show internal

consistency with a large UK sample of older people,

given that Heerink and colleagues had worked with

older people in the Netherlands. Heerink et al. (2008,

2009, 2010) themselves note the need for testing with

larger samples of participants and participants in

difference circumstances.

Six of the 11 constructs showed adequate

consistency of items and consistency across three

Measuring Older People’s Attitudes Towards Personal Robots

115

different types of personal robots, which was

encouraging . However, there were constructs which

showed low consistency (Facilitating Conditions,

Perceived Adaptability, Perceived Ease of Use,

marginally Anxiety) or inconsistent results

(Perceived Ease of Use, Social Presence). Some of

these issues may have been due to differences

between the particular robots and the robot types,

although one would hope for consistency of items

across a range of robots.

Therefore, a series of PCAs were conducted on

the ratings to investigate whether there was a more

meaningful set of underlying components. These

analyses showed very similar grouping of attitude

ratings for two of the personal robots, Afobot and

Sanbot. Only one group of ratings, related to social

presence, were different for MiRo. MiRo is an

animal-like robot (its developers deliberately based

MiRo’s design on a number of small mammals

kittens, dogs, rabbits, to make a “generic

mammalian” form, Collins et al., 2015), whereas

Afobot and Sanbot have more human-like qualities,

which may account for this difference. Although

Afobot does not look very human-like, it speaks in a

human way. Therefore, we propose that all three

components (Positive User Experience,

Anxiety/Negative Usability, and Social Presence)

may be useful high level components of attitudes to

personal robots which can be helpful in studying

robotic technologies to support older people. Further

research and psychometric development of a scale

(DeVellis, 2003) incorporating these components is

needed, using different robots within each type,

particularly to tease out the role social presence as a

separate component in pet robots such as MiRo.

An analysis with the new sets of components, to

investigate differences in the attitudes of the UK

sample of older people towards the three personal

robots. There were highly significant differences

between the robots overall and on all three

components. Of particular interest was the fact that

MiRo received the most positive ratings, due to

significantly higher social presence ratings (an

interesting point, given the issues of how social

presence grouped with other attitudes for MiRo).

This was not surprising, as MiRo was explicitly

designed to interact with the user at an emotional

level and to have numerous characteristics of a pet

animal. Thus, the attitude components do clearly

discriminate between these three different personal

robots of three different types.

The research has several important limitations

that require discussion. Firstly, participants only

viewed videos of the personal robots and did not

interact with them face-to-face. This has several

consequences. Participants did not get a chance to

explore the robot’s behaviour themselves and its

reactions to their own behaviour. This may be

particularly important of issues of perceived

adaptability, which would have been hard to judge

from just watching a video. In addition, as we wanted

to keep the videos short in an online study which

included a lot of ratings and questions for the

participants, so each video only included one example

of each robot type. This had both advantages and

disadvantages. It meant that the participants were

reacting to a specific personal robot, so the ratings are

not a combination of reactions to potentially slightly

different robots within one type. However, they only

represent one example of that robot type and further

research is vital on each robot type and between robot

types to understand commonalities and differences (a

point also made by Heerink et al., 2008, 2009).

Finally, although we tried very hard to make the

videos comparable and show a range of situations and

functions for each personal robot, we used publicly

available videos, so the three videos were not a tightly

controlled set and this may have introduced

differences we are not completely aware of.

Another limitation was that the study was

conducted online, rather than face-to-face, which

would have enabled us to recruit a more diverse

sample of older people. However, the study required

data from a large number of participants for the

analyses we wished to conduct, and we did not have

the resources or stamina to undertake face-to-face

sessions with nearly 250 older people. In addition, as

the study was conducted towards the end of the

COVID-19 pandemic, we were also very concerned

that if we planned for face-to-face sessions, another

social distancing situation might arise and we would

not be able to proceed with the study. Finally, we

were concerned that older people might be reluctant

to participate in face-to-face sessions because of the

risk of COVID-19 infection. However, we chose the

three personal robots in the study because we do have

each of these robots in our laboratories. We are

planning smaller scale follow-up studies in which

older people will actually interact with the robots.

This will allow us to compare the attitudes developed

from watching videos to the attitudes developed from

live interaction. An investigation of such differences

will be of interest in itself, as in the future older

people may well choose a personal robot from

watching a video on television or the Internet, rather

than being able to interact with it live.

A final limitation is that the sample of older

people was an opportunistic one. As the study was

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

116

conducted online and required people to be able to

access the questionnaire software and watch videos

embedded in the questionnaire, this may mean the

sample is biased towards participants more proficient

and comfortable with technology. Certainly, the fact

that participants rated themselves as significantly

above the midpoint of the scale on confidence with

computers and the Internet suggests this. We used the

Prolific participant recruitment website, which also

requires a certain confidence with the internet and

interest in new technology, but we also made

considerable efforts to recruit older participants

through other routes as well, in order to create a more

heterogeneous sample. The wide range of

occupations of participants showed that they were

quite a diverse range of British society. However,

they were also relatively young older people – the

majority were in their 60s, so this is definitely a study

about the attitudes of “young old” UK people to

personal robots.

In conclusion, this study has made a contribution

towards developing a questionnaire to easier measure

older people’s attitudes to personal robots. It has

extended the work on the Almere model with a large

sample of older people in the UK, showing an

underlying grouping of attitudes to personal robots

which may be useful in future work. Given that it is

highly likely that older people will increasingly be

using personal robots to support themselves in the

future, having simple methods for developing a clear

understanding of their attitudes to such technology is

very important. The study has also made a initial

contribution to understanding the attitudes of older

people in the UK to three types of personal robot that

they may find useful and companionable in the near

future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the participants in this

study for their time and efforts, which were quite

considerable. We would also like to thank Jing Hou

for assisting with the first round of data collection for

the study.

REFERENCES

Agrigoroaie, R.M., & Tapus, A. (2016). Developing a

Healthcare Robot with Personalized Behaviors and

Social Skills for the Elderly. Proceedings of the

Eleventh ACM/IEEE International Conference on

Human Robot Interaction. pp. 589–590. IEEE Press.

Ambient Assisted Living Association (n.d.) Aging well in

the digital world, http://www.aal-europe.eu.

Bartneck, C., Kulić, D., Croft, E., & Zoghbi, S. (2009).

Measurement instruments for the anthropomorphism,

animacy, likeability, perceived intelligence, and

perceived safety of robots. International Journal of

Social Robotics. 1, 71–81.

Collins, E.C., Prescott, T.J., Mitchinson, B., & Conran, S.

(2015). MIRO: A versatile biomimetic edutainment

robot. Proceedings of the 12th International

Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment

Technology (ACE '15). ACM Press.

Davis, F.D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology.

Management and Information Systems Quarterly,

13(3), 319 – 340.

Eftring, H., & Frennert, S. (2016). Designing a social and

assistive robot for seniors. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie

und Geriatrie, 1–8.

El Kamali, M., Angelini, L., Caon, M., Andreoni, G.,

Khaled, O.A., & Mugellini, E.: (2018). Towards the

NESTORE e-Coach: A Tangible and Embodied

Conversational Agent for Older Adults. Proceedings of

the 2018 ACM International Joint Conference and 2018

International Symposium on Pervasive and Ubiquitous

Computing and Wearable Computers. pp. 1656–1663.

ACM Press.

Feil-Seifer, D., & Matarić, M.J. (2011). Socially assistive

robotics. Robotics & Automation Magazine, 18, 24–31.

Frennert, S. (2020). Expectations and sensemaking: Older

People and Care Robots In Gao, Q., & Zhou, J. (Eds.),

Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population.

Technology and Society (HCII 2020). Lecture Notes in

Computer Science 12209. Springer.

Hebesberger, D., Dondrup, C., Koertner, T., Gisinger, C.,

& Pripfl, J. (2016). Lessons learned from the

deployment of a long-term autonomous robot as

companion in physical therapy for older adults with

dementia: a mixed methods study. Proceedings of the

Eleventh ACM/IEEE International Conference on

Human Robot Interation. ACM Press.

Heerink, M., Kröse, B., Evers, V., & Wielinga, B. (2008).

The influence of social presence on acceptance of a

companion robot by older people. Journal of Physical

Agents, 2, 33–40.

Heerink, M., Krose, B., Evers, V., & Wielinga, B. (2009).

Measuring acceptance of an assistive social robot: a

suggested toolkit. Proceeding of RO-MAN 2009: The

18th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and

Human Interactive Communication. pp. 528–533.

Heerink, M., Kröse, B., Evers, V., & Wielinga, B. (2010).

Assessing acceptance of assistive social agent

technology by older adults: The Almere model.

International Journal of Social Robotics. 2, 361–375.

Karunarathne, D., Morales, Y., Nomura, T., Kanda, T., &

Ishiguro, H. (2019). Will older adults accept a

humanoid robot as a walking partner? International

Journal of Social Robotics, 11, 343–358.

Khosla, R., & Chu, M.-T. (2013). Embodying care in

Matilda: An affective communication robot for

Measuring Older People’s Attitudes Towards Personal Robots

117

emotional wellbeing of older people in Australian

residential care facilities. ACM Transactions on

Management Information Systems, 4, 18:1--18:33.

Lazar, A., Thompson, H.J., Piper, A.M., & Demiris, G.

(2016). Rethinking the design of robotic pets for older

adults. Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on

Designing Interactive Systems. pp. 1034–1046. ACM

Press.

Li, J., Louie, W.-Y.G., Mohamed, S., Despond, F., & Nejat,

G. (2016). A Uuer-Study with Tangy the bingo

facilitating robot and long-term care residents. IEEE

International Symposium on Robotics and Intelligent

Sensors.

López Recio, D., Márquez Segura, L., Márquez Segura, E.,

& Waern, A. (2013). The NAO models for the elderly.

ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot

Interaction, 187–188.

Monekosso, D.N., Flórez-Revuelta, F., & Remagnino, P.

(2015). Guest Editorial. Special Issue on Ambient-

Assisted Living: Sensors, Methods, and Applications.

IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems. 45,

545–549 (2015).

Mundher, Z.A., Zhong, J.: A Real-Time Fall Detection

System in Elderly Care Using Mobile Robot and Kinect

Sensor. International Journal of Materials, Mechanics

and Manufacturing, 2, 133–138.

Mynatt, E.D., Essa, I., & Rogers, W. (2000). Increasing the

opportunities for aging in place. Proceedings of the

Conference on Universal Usability, 65–71.

Nomura, T., Kanda, T., Suzuki, T., & Kato, K. (2008).

Prediction of human behavior in human-robot

interaction using psychological scales for anxiety and

negative attitudes toward tobots. IEEE Transactions on

Robotics. 24, 442–45.

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric Theory

(3rd edition.) McGraw-Hill.

Petrie, H., & Darzentas, J.S. (2020). Digital Technology for

Older People: A Review of Recent Research. In:

Simeon Yates and Ronald E. Rice (ed.) The Oxford

Handbook of Digital Technology and Society. Oxfored

University Press.

Petrie, H., Darzentas, J.S., & Carmien, S. (2018). Intelligent

support technologies for older people: An analysis of

characteristics and roles. Proceedings of CWUAAT

2018: Breaking Down Barriers: Usability, Accessibility

and Inclusive Design. 89–99.

Rosales, P., Vega, A., De Marziani, C., Gallardo, J.I., Pires,

J., & Alcoleas, R.: (2017). Monitoring system for

elderly care with smartwatch and smartphone. XXIII

Congreso Argentino de Ciencias de la Computación

(La Plata, 2017). 1020–1029.

Samaddar, S., & Petrie, H. (2020). What Do Older People

Actually Want from Their Robots? In Miesenberger,

K., Manduchi, R., Covarrubias Rodriguez, M., &

Peňáz, P. (Eds.), Computers Helping People with

Special Needs (ICCHP 2020.) Lecture Notes in

Computer Science 2376. Springer.

Sinn, M., & Poupart, P. (2011) Smart walkers!: Enhancing

the mobility of the elderly. Proccedings of the 10th

International Conference on Autonomous Agents and

Multiagent Systems - Volume 3. pp. 1133–1134.

International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and

Multiagent Systems.

Smarr, C.A., Prakash, A., Beer, J.M., Mitzner, T.L., Kemp,

C.C., & Rogers, W.A. (2012). Older adults’ preferences

for and acceptance of robot assistance for everyday

living tasks. Proceedings of the Human Factors and

Ergonomics Society. 153–157.

United Nations (2019). World Population Ageing 2019.

New York: United Nations.

United Nations (2022). World population prospects 2022:

Summary of results. New York: United Nations.

DeVellis, R.F.: (2003). Scale development: theory and

applications (2

nd

Edition). Sage.

Wada, K., & Shibata, T. (2007). Robot therapy in a care

house - Change of relationship among the residents and

seal robot during a 2-month long study. Proceedings -

IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human

Interactive Communication, 23, 107–112.

ICT4AWE 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

118