The Preservation of Heritage in a School Campus with Augmented

Reality (AR) and Game-Based Learning

P. B. A. Vu

1a

, Q. Ying

1b

and Kenneth Y. T. Lim

2c

1

Independent Researcher

2

National Institute of Education, Singapore

Keywords: Augmented Reality, Game-Based Environment, Cultural Heritage, Serious Games, Situational Interest.

Abstract: Serious games have showcased tremendous potential in transforming the way we teach and learn. This paper

explores the potential affordances of Augmented Reality (AR) game-based learning, specifically in the

context of preserving school heritage. The AR game-based learning experience is proposed to increase

students’ knowledge of their school’s heritage. By incorporating digital technology and story-telling, the game

is also proposed to make the subject of school heritage more tangible for the enhancement of learning. The

study involves 10 students playing an AR adventure role-playing game (RPG) which uses device location

within the campus of Hwa Chong Institution, Singapore, to trigger in-game events. To assess the effectiveness

of the AR game-based experience as a medium for learning, a general survey is used to collect feedback about

the gameplay experience, while a Situational Interest survey collects data about participants’ situational

interest, which emerges in response to the learning environment created, using the Situational Interest Scale

(Chen et al., 1999). Results confirmed a positive correlation between players’ situational interest and

absorption of information, shed light on the significance of game design elements in influencing the gameplay

experience, and pointed to specific rooms for improvement for future AR game-based learning environments.

It is hoped that this paper will contribute to an understanding of the wider effectiveness of game-based

learning environments in educational contexts.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

1.1.1 Serious Games and Game-Based

Learing

Serious Games (SGs) are video games where the

main purpose is not entertainment (Manuel et al.,

2019). Game-based learning, i.e. serious games used

for education, is defined as “learning that is facilitated

by the use of a game” (Whitton, 2012). Game-based

environments are effective in enhancing students’

learning through promoting experimental learning

and active construction of knowledge i.e. learning

through experience or learning-by-doing (Liarokapis

et al., 2017; Cozza et al., 2021). Their success has also

been linked to alignment with proven pedagogy.

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-3735-2915

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-8724-0640

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3756-6625

Use of SGs for school heritage awareness and

preservation can be classified under “place-based

learning”, which is defined as "learning that is rooted

in what is local—the unique history, environment,

culture, economy, literature, and art of a particular

place” (Smith and Sobel, 2010). For example,

Wisconsin, a state in the United States (US), used

location-based games (LBGs) for the Greenbush

Cultural Tour, a year-long learning project that

involves students helping to develop an AR-based

game “MadCity Mystery”. Through repeated

observations and hands-on experiences with elements

in the “Place”, students form a pattern of culture and

community which deepened their sense of place and

connection to Greenbush (Olson and Wagler, 2011).

Vu, P., Ying, Q. and Lim, K.

The Preservation of Heritage in a School Campus with Augmented Reality (AR) and Game-Based Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0012755400003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 701-710

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

701

1.1.2 Augmented Reality

Augmented Reality (AR) technology, defined as the

augmentation of the physical real-world environment

through the addition of virtual computer-generated

information (Carmigniani and Furht, 2011), is

commonly used to enhance game-based learning

environments. Ying et al. (2021) attribute this to the

elements of gamification and immediate feedback

that can capture and retain learners’ interest and

attention. It is proposed that contemporary game-

based learning environments should employ AR

technologies for student-centred learning instead of

relying on expert-led instructional methods (Lim and

Lim, 2020).

1.1.3 Situational Interest

Situational Interest is defined as a temporary state

aroused by specific features of a situation, task, or

object (Schiefele, 2009). Many studies have

associated students’ situational interest in learning

activities, which encompasses factors such as

enjoyment, curiosity, and attention, with better

learning and knowledge absorption. Chen et al.

(1999) developed a Situational Interest Scale to

identify high interest versus low interest activities.

1.1.4 Learning of School Heritage

School heritage is the cultural heritage of an

educational institution, which refers to any tangible

and intangible assets inherited from the past of that

institution. Balela and Mundy (2015) outlined the

following four dimensions of cultural heritage: Arts

and Artefacts, Environment, People and History.

While SGs have generated significant enthusiasm

in the field of cultural heritage preservation (Yun,

2023; DaCosta and Kinsell, 2023), there is a

noticeable lack of representation when it comes to

school heritage preservation. In undertaking this

study, we consider the heritage and history of a school

as something to be valued and passed down to future

generations. Familiarity with school heritage is

assumed to be able to strengthen the bonds within the

school community, consisting of students, alumni,

and staff.

This study seeks to investigate whether the

proposed benefits of game-based learning

environments with regards to the learning of cultural

heritage and triggering situational interest, can be

applied to the preservation of school heritage. For

example, location-based games (LBGs) have been

praised for its effects in stimulating students’

imagination (Lehto et al., 2020), improving learning

motivation (Volkmar et al., 2018), encouraging

reflection on history (Jones et al., 2019) and fostering

emotional connection to cultural heritage (Othman et

al., 2021).

Hwa Chong Institution in Singapore was chosen

as the basis of the game designed in this study. The

school was founded in 1919 and boasts a rich

heritage, having been through World War II and

bearing witness to student activism throughout the

1930s to 1960s (Liu and Wong, 2004). As a Special

Assistance Plan (SAP) school that seeks to “develop

effectively bilingual students who were inculcated

with traditional Chinese values” (Sim, n.d), the

school plays an important role in promoting Chinese

culture in an increasingly diverse Singapore. The

abundance of urban legends and ghost stories based

around the school’s history, also known as “informal,

non-official heritage” (Barrère, 2016) have inspired

some elements in the game’s narrative, such as

talking statues with glowing eyes and mysterious

ghost figures loitering around the Clock Tower.

1.2 Scope of Investigation

This project explores the potential affordances of

Augmented Reality (AR) game-based learning in

preserving school heritage, by assessing student

players’ situational interest in a game based in their

campus as well as their perception of the strengths

and limitations of the medium.

Our objective is ultimately to explore the potential

affordances of AR in making school heritage more

tangible as a means of preservation.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Location-Based Game

A game-based learning activity using Augmented

Reality (AR) was designed using the Taleblazer

platform developed by the MIT STEP lab, and set in

Hwa Chong Institution, Singapore. The study

involved 10 student participants from the school, to

afford them a scaffolded experience as they explore

the campus with a heritage perspective.

The game was constructed as an AR adventure

role-playing game (RPG) which uses device location

within the boundaries of the campus to trigger in-

game events. Players were required to physically

access points of interest (POIs), identified with

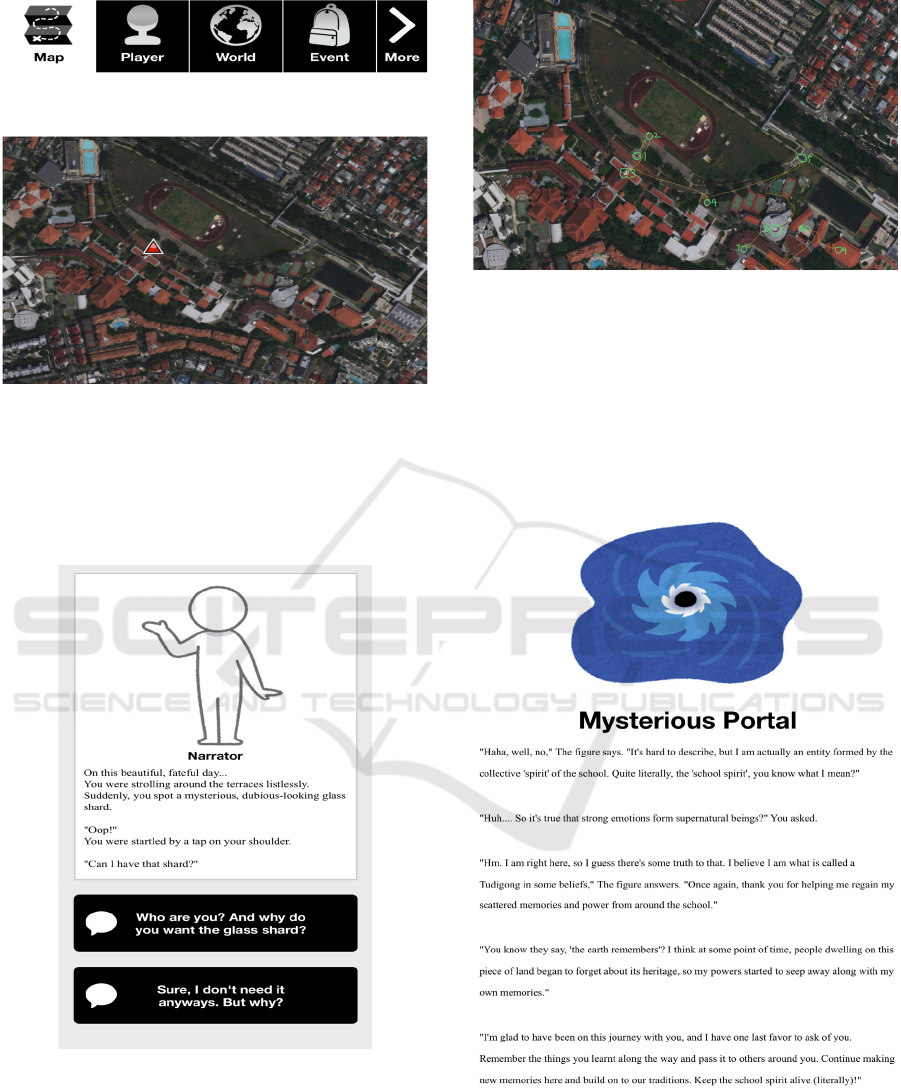

markers on the in-game map (Figure 1).

ERSeGEL 2024 - Workshop on Extended Reality and Serious Games for Education and Learning

702

Figure 1: Screenshot of the in-game map with the first POI

marked by the red triangle icon.

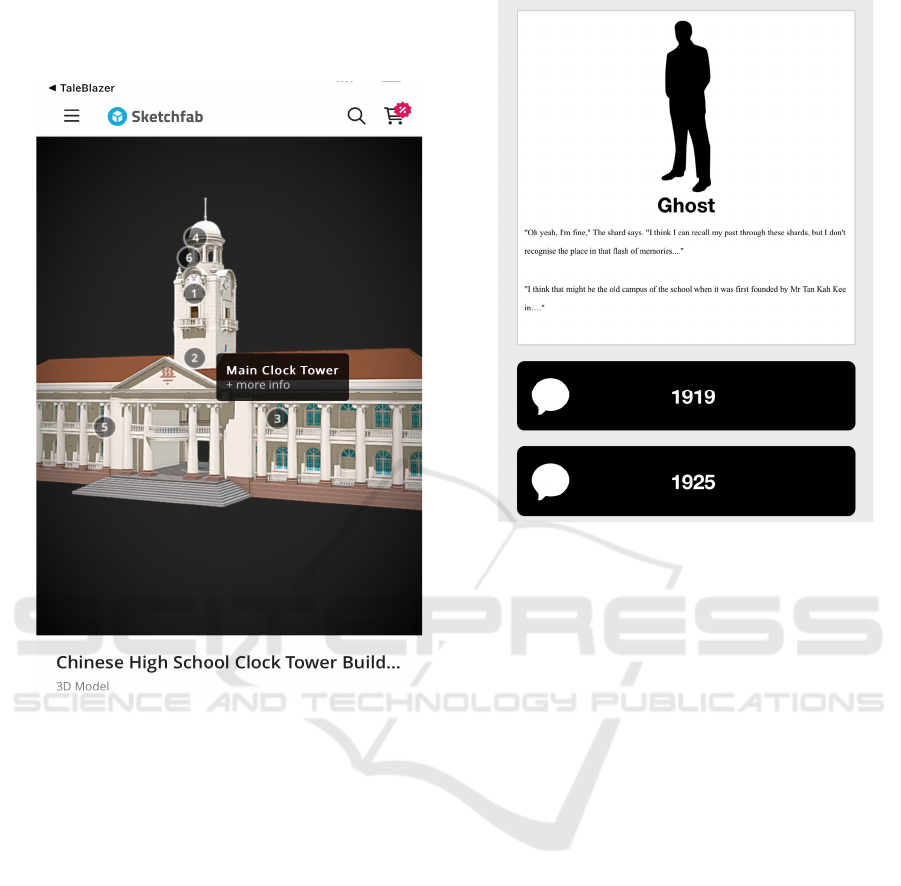

As an adventure RPG, the game’s narrative revolves

around an unnamed playable character (“the player”)

assisting a mysterious ghost figure in its search for

strange ‘shards’ around the school (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A screenshot of the game at the first POI, where

players are introduced to the mysterious ghost figure.

The players were required to access each POI in

order to progress through the game story. For the sake

of simplicity usually preferred for school tours, the

order of the POIs is linear with a fixed ending (Figure

3).

Figure 3: A bird’s eye view map of the school campus, with

the sequence of in-game POIs marked in green.

With each POI reached and a new shard is

collected, players discover more information about

the school’s heritage and finally unveil the identity of

the ghost at the last POI (Figure 4). Information was

given through in-game narration, dialogues between

the player and the non-playable characters (NPCs), or

multimedia resources embedded in the game.

Figure 4: A screenshot of the game showing part of the

narration and the dialogues between the player and the non-

playable “supernatural” character.

The multimedia resources served to complement

the textual information given to players through

character dialogues and narration, such as

The Preservation of Heritage in a School Campus with Augmented Reality (AR) and Game-Based Learning

703

photographs of past school events, and links to a

website with a maneuverable 3D model of a heritage

monument on the campus (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A maneuverable 3D model by the National

Heritage Board of the Clock Tower national monument on

the Hwa Chong Institution campus, which players access

during the game.

Quiz segments were included in the game (Figure

6) to prompt players to search for relevant

information either in the physical environment or on

the internet, such that the learning activity is

meaningfully situated in a relevant context (de Souza

e Silva and Delacruz, 2006).

2.2 Research Design

A mixed methods concurrent triangulation design

was adopted in this study to combine qualitative and

quantitative approaches. Quantitative data from the

Situational Interest Scale (see 3.3) and qualitative

data from participant feedback (see 3.2) were

compared to determine if there is convergence,

differences, or some combination (Creswell, 2009).

Figure 6: A screenshot of one of the quizzes in the game.

2.3 Situational Interest Scale

This study used the Situational Interest Scale devised

by Chen et al (1999), which includes 24 items spread

across 5 dimensions of situational interest– Novelty,

Challenge, Exploration Intention, Instant Enjoyment,

and Attention Demand– as well as the Total Interest

domain. Each item was to be scored on a 5-point

Likert scale, with 5 being Very true. The items of the

Exploration Intention dimension were modified from

the original context in physical education to fit the AR

game-based learning activity in this study.

In the study, the items were shown to participants

in a randomised sequence using a Google Form

survey which also collected qualitative feedback.

The participants played the game on campus

under the researcher’s supervision. Subsequently, the

survey hosted on Google Forms was disseminated via

WhatsApp text and completed by the participants

individually.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Content Retention

The student participants were asked to score how

much they knew about their school heritage before

ERSeGEL 2024 - Workshop on Extended Reality and Serious Games for Education and Learning

704

and after the game on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1

being Not at all. The knowledge score increased from

a mean score of 2.1 before the game to 4 after the

game, showing content retention from the game in the

short term. However, further data collection for long-

term content retention was not undertaken due to the

time frame given for the study.

3.2 Thematic Analysis

In this study, a Google form was used to collect

qualitative feedback on the game experience from all

participants, with the following prompts:

1. What did you like about the game?

2. What did you not like about the game?

The data was first read without coding. Then,

individual statements were analysed to highlight

significant text, such as “narration”, “plot”, and

“GPS” (Global Positioning System), and categorised

into the limitations and strengths of the game. To

minimise interpretation bias, 2 researchers were

involved in reviewing the data. The themes that

ultimately emerged from the analysis were Content,

Game Mechanics, and External Factors (see

Appendix A).

Many players chose to comment on the game’s

narrative, plot, or dialogues, which indicates that their

situational interest is influenced by these factors. In

particular, participant P8, the only one who proposed

the game should have a branching storyline instead of

a linear one, also had the lowest average score for

Exploration Intention.

The game’s laggy GPS was pointed out by 3 out

of the 10 participants, which is more than that of any

other limitations. This could be because such

technical problems take away the immersion factor

that AR game-based environments are often praised

for, or simply because the obstruction to the gameplay

is a source of annoyance for players. Regardless, it

meant that players considered technical problems in

the game mechanics to be a critical limitation, which

corroborates our literature that inaccurate GPS

signals can cause unpleasant gaming experiences

(Fränti and Fazal, 2023).

3.3 Situational Interest Scale

The scores of 10 student participants for the

Situational Interest Scale (Chen et al., 1999) were

recorded. The distribution of the participants’ scores

in the 4 dimensions and also the Total Interest domain

is represented on the respective histograms.

All items in the scale were scored on a 5-point

Likert scale, from 1 (Very untrue) to 5 (Very true). A

total of 24 items were shown to participants in a

randomised order to check consistency in answers,

and reverse coding was not used. The individual

participant’s score for each dimension of the scale

was recorded by taking the mean score of their

answers to the 4 items under the respective

dimensions.

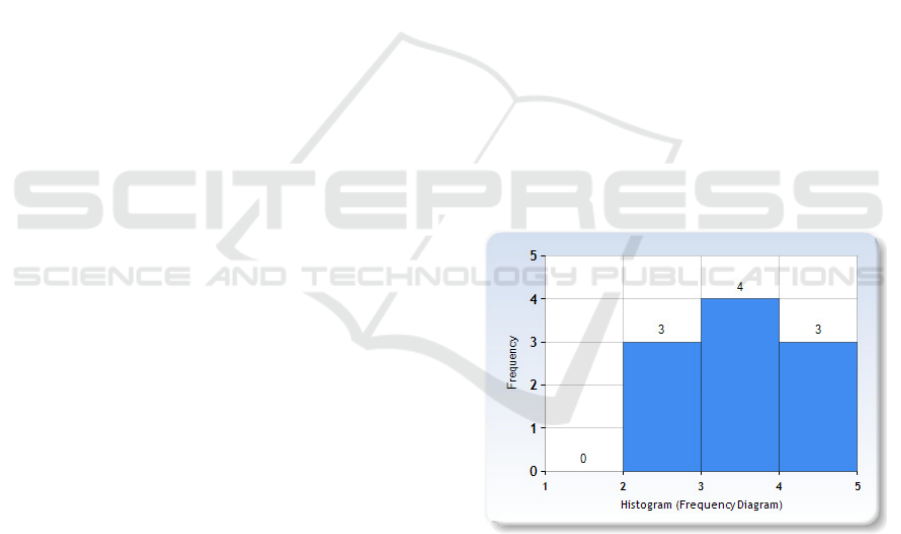

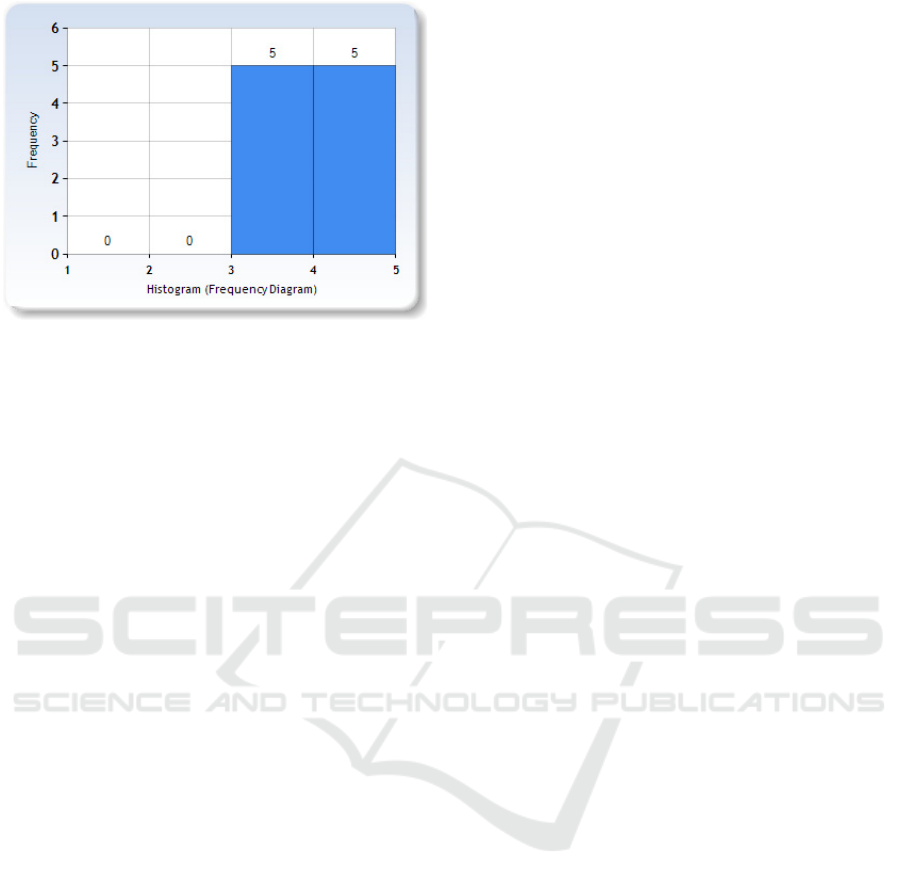

For the Exploration Intention dimension, Figure 7

illustrates that 70% of the participants fall within the

range of 3 to 5. The participants with mean scores

below 3 in this dimension suggested distinct

limitations of the game experience across content

presentation and game mechanics, from the game’s

lack of a “branching storyline”, lack of coverage on

“more secluded places that we usually don’t go to”,

to the game design which requires players to walk.

The player feedback substantiates existing literature

that a location target layout that creates a clear linear

sequence may not present a sufficient challenge and,

in turn, reduce player enjoyment (Schiefele, 2009).

2 out of 3 participants with mean scores of 4 and

above noted the content presentation of an

“interesting”, “coherent” narrative as a strength,

while the other participant falling in this range

indicated the game’s incorporation of information

that can be found physically to be a strength.

Figure 7: Histogram of Exploration Intention dimension.

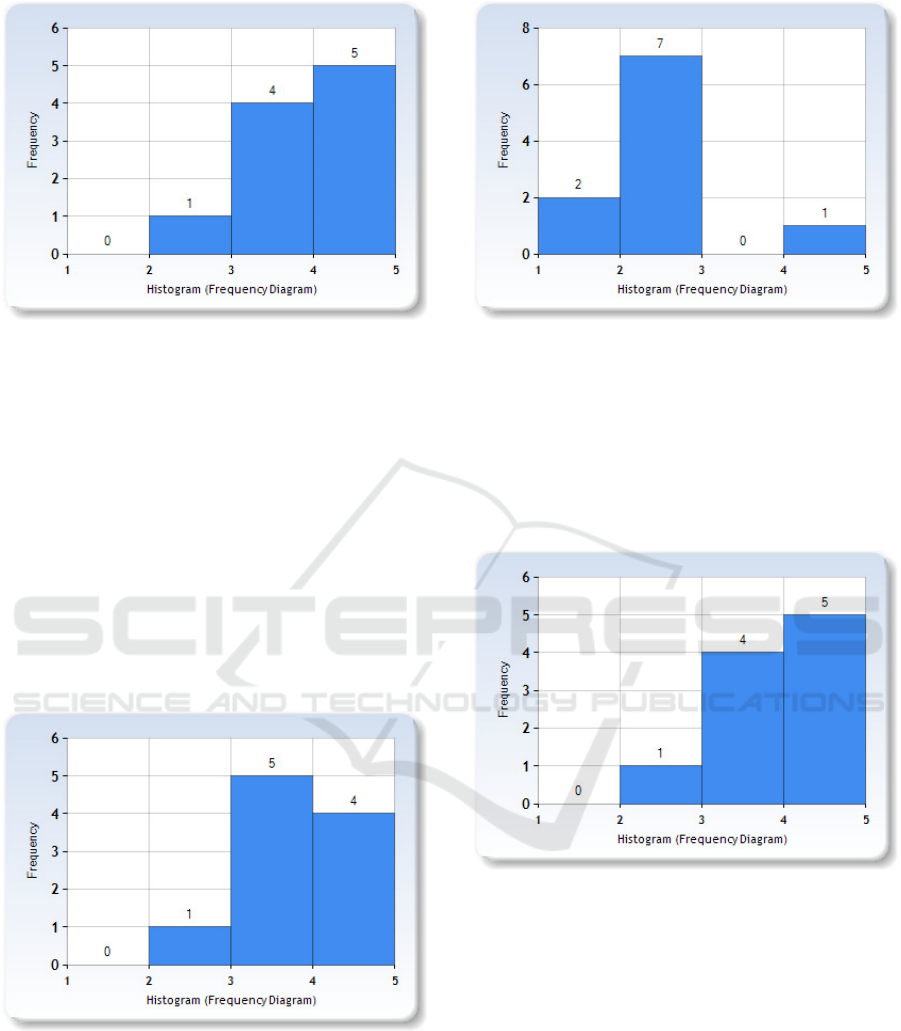

Figure 8 shows that 90% of the participants scored

the Instant Enjoyment dimension positively with

mean scores of 3 and above. Of the 5 participants

falling in the 4 to 5 score range, 4 highlighted content

presentation as the strength of the game. It stands as

a logical inference that content presentation is a key

influence on enjoyment. The outlier participant who

had a mean score below 3 in this dimension

particularly mentioned a lack of interest in the topic

of the game.

The Preservation of Heritage in a School Campus with Augmented Reality (AR) and Game-Based Learning

705

Figure 8: Histogram of Instant Enjoyment dimension.

In the Attention Demand dimension, 90% of the

participants had mean scores of 3 and above, as

represented by Figure 9. It is significant to mention

that all 4 participants falling in the highest score range

of 4 to 5, also scored 4 and above in the Instant

Enjoyment dimension. This aligns with reasonable

expectations that the participants who enjoyed the

game the most also had higher attention quality

during the experience, as enjoyment has been linked

with better concentration in students (Lucardie,

2014). It was noted that the outlier participant scoring

below 3 in this dimension was also scoring below 3

in the Exploration Intention dimension, citing the

walking required by the game as a limitation.

Figure 9: Histogram of Attention Demand dimension.

With regards to the Challenge dimension, 90% of

the participants faced little to no challenge playing the

game, as evidenced by Figure 10. It is worth

highlighting that the outlier participant in this

dimension was observed struggling to find the correct

answer for some quiz segments in the game, which

may have impacted the score.

Figure 10: Histogram of Challenge dimension.

Figure 11 illustrates that 90% of the participants

scored the Novelty dimension at 3 or above,

supporting our literature review that there had not yet

been a widespread application of serious games in

education (Almeida and Simoes, 2019) despite the

increasing abundance of such games and the

availability of technology.

Figure 11: Histogram of Novelty dimension.

Overall, all participants positively scored the

Total Interest dimension, as shown by Figure 12,

indicating an overall positive and engaging game

experience for the 10 participants. Referencing Figure

8, this result also substantiates the study by Chen et

al. (2001) that Challenge may play a less important

role in influencing situational interest, especially in

the context of a task that is more physical, as the game

experience constructed for this study does not require

any conceptual understanding but requires physical

movement.

ERSeGEL 2024 - Workshop on Extended Reality and Serious Games for Education and Learning

706

Figure 12: Histogram of Total Interest dimension.

4 DISCUSSION

Both quantitative and qualitative results reflected

fairly similar answers across 10 participants, with

reasonable outliers to support existing literature on

external factors that contribute to variances in players’

situational interest besides the gameplay experience

itself, such as environmental variables e.g. teaching

styles, learning duration or grouping (Chen et al.,

2001). This reveals that, overall, HeritageByte as an

augmented reality game-based learning environment

has achieved an expected degree of success.

To further assess the degree of effectiveness of the

gameplay experience, we rely on 2 criteria -

situational interest (which we sometimes refer to

interchangeably with player enjoyment) and content

retention. On situational interest, 100% of

participants indicated some level of interest (see

Figure 10), which is significant because our literature

review has established interest and general

engagement as important factors in learners’

motivation. On content retention, 100% of

participants indicated an increase in their knowledge

of the subject matter (i.e. the heritage of the school)

after the game by at least 1 point on a 5-point Likert

scale. This result corroborates the literature on the

potential of hybrid reality games in teaching site-

specific history (de Souza e Silva and Delacruz,

2006). This also substantiates existing literature that

serious games can “[provide] concrete, compelling

contexts” for cultural heritage content which may be

harder to appreciate when de-contextualized

(Economou, 1998; Belotti, 2012).

An unavoidable limitation of any serious games

used for the learning of school heritage is the presence

of players’ inherent prejudice against history as a

boring, tedious and content-heavy topic. This is one

of the key motivations behind the increasing

incorporation of serious games into the teaching of

these topics. Specifically, the potential of serious

games as a medium for heritage learning is due to the

belief that the fun and engaging gameplay experience

is able to combat learners’ previous lack of interest in

the topic, which is to say, triggering sufficient

situational interest for them to voluntarily learn more

about the topic. However, in our study, despite the use

of a serious game, which was unanimously agreed on

by all players as being able to pique their enjoyment

(Instant Enjoyment) and curiosity to learn more

(Exporation Intention), one participant (P2) still noted

the lack of interest in the topic as the factor that had

significantly reduced their interest in the game. It could

either be perceived as an outlier or that the design

limitations of the game raised by various other players

had reduced the overall effectiveness of the game.

In addition, a small sample size was used in this

study due to time restraints. The student participants

involved in this study were aged 17-18 years old,

hence the findings of this study may not apply to other

learner groups, for example, younger children, due to

factors such as the development of sustained attention

(Hobbiss and Lavie, 2024). Additionally, the game

used in this study was constructed around the specific

heritage context, and unique geography of the campus

chosen. Hence, future research is required to attain a

deeper understanding of principles of design that

apply to all campuses in developing such location-

based games.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This project aims to explore the potential for a more

widespread application of AR game-based learning

environments in delivering content about school

heritage. Overall, our results corroborate existing

research on the effectiveness of this medium in

producing positive knowledge retention and

engagement during the learning process.

The study shed light on the significance of game

design elements, including the presentation aspect

e.g. narrative, and the technical aspect e.g. GPS, on

players’ situational interest. Most significantly, the

content presentation aspect of the game had a strong

positive influence on the Instant Enjoyment and

Exploration Intention dimensions, which suggests the

narratives employed in the adventure RPG genre

positively influence situational interest in this use

case. We can conclude that narratives in AR game-

based environments may be key to making school

The Preservation of Heritage in a School Campus with Augmented Reality (AR) and Game-Based Learning

707

heritage more tangible, as a means of preservation.

Future work can delve into the relationship between

specific game elements and the dimensions of

situational interest to develop design principles in

crafting such AR game-based experiences.

Feedback on the game’s lack of branching

narratives and lack of content coverage on more niche

locations corroborate the common perception of

serious games being too boring and predictable to

keep players engaged. Whereas these limitations were

deliberate design choices to ensure a reasonable

walking distance in a single game session (Fränti and

Fazal, 2023), it raises the question of the balance

between the pedagogical and entertainment aspects of

such a serious game. More secluded locations and

branching narratives in a location-based game, where

learning tasks are connected to relevant POIs, will

likely deviate from the “serious” aspect of the game

but may increase player motivation through perceived

in-game autonomy (Ryan et al., 2006). Future work

should consider carefully the balance between the

“serious” and “game” aspects while designing game-

based learning environments to ensure both

entertainment and education criteria are met (Manuel

et al., 2019).

Ultimately, this study was fruitful in gaining some

insight into the potential of employing AR game-

based learning environments in the subject of school

heritage preservation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Dr

Lim Yang Teck Kenneth from the National Institute

of Education for his invaluable guidance and

feedback throughout the project; along with his team,

Ahmed and Richard, who generously provided

technical knowledge and expertise.

REFERENCES

Almeida, F., & Simoes, J. (2019). The role of serious

games, gamification and Industry 4.0 Tools in the

Education 4.0 Paradigm. Contemporary Educational

Technology, 10(2), 120–136. https://doi.org/10.30935/

cet.554469

Balela, M.S., & Mundy, D.P. (2015). Analysing Cultural

Heritage and its Representation in Video Games.

DiGRA '15 - Proceedings of the 2015 DiGRA

International Conference, 12.

Barrère, C. (2016). Cultural heritages: From official to

informal. City Cultural Society, 7(2), 87–94.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2015.11.004

Bellotti, F., Berta, R., De Gloria, A., D'ursi, A. and Fiore,

V. (2012). A serious game model for cultural heritage.

Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage

(JOCCH), 5. 10.1145/2399180.2399185.

Carmigniani, J., & Furht, B. (2011). Augmented reality: An

overview. Handbook of Augmented Reality, 3-46.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0064-6_1

Chen, A., Darst, P. W., & Pangrazi, R. P. (1999). What

constitutes situational interest? Validating a construct

in physical education. Measurement in Physical

Education and Exercise Science, 3(3), 157-180.

Chen, A., Darst, P. W., & Pangrazi, R. P. (2001). An

examination of situational interest and its sources.

British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(3), 383–

400. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158578

Cozza, M., Isabella, S., Di Cuia, P., Cozza, A., Peluso, R.,

Cosentino, V., Barbieri, L., Muzzupappa, M., & Bruno,

F. (2021). Dive in the Past: A Serious Game to Promote

the Underwater Cultural Heritage of the Mediterranean

Sea. Heritage, 4(4), 4001-4016. https://doi.org/10.33

90/heritage4040220

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative,

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.).

Sage Publications, Inc.

DaCosta, B., & Kinsell, C. (2023). Serious Games in

Cultural Heritage: A Review of Practices and

Considerations in the Design of Location-Based

Games. Education Sciences, 13(1), 1-25.

https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010047

de Souza e Silva, A., & Delacruz, G. C. (2006). Hybrid

reality games reframed. Games and Culture, 1(3), 231–

251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412006290443

Economou, M. (1998) The evaluation of museum

multimedia applications: lessons from research.

Museum Management and Curatorship, 17(2), 173-

187. doi: 10.1080/09647779800501702

Fränti, P., & Fazal, N. (2023). Design principles for content

creation in location-based games. ACM Transactions

on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and

Applications, 19(5s), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3

583689

Hobbiss, M. H., & Lavie, N. (2023). Sustained selective

attention in adolescence: Cognitive development and

predictors of distractibility at school. Journal of

Experimental Child Psychology, 238, 105784.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2023.105784

Jones, C., & Papangelis, K. (2019). Reflective Practice:

Lessons Learnt by Using Board Games as a Design

Tool for Location-Based Games. Lecture Notes in

Geoinformation and Cartography, 291–307.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14745-7_16

Lehto, A., Luostarinen, N., & Kostia, P. (2020). Augmented

Reality Gaming as a Tool for Subjectivizing Visitor

Experience at Cultural Heritage Locations—Case

Lights On!. Journal on Computing and Cultural

Heritage, 13(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3415142

Liarokapis, F., Kouřil, P., Agrafiotis, P., Demesticha, S.,

Chmelík, J., & Skarlatos, D. (2017). 3D modelling and

mapping for virtual exploration of underwater

archaeology assets. The International Archives of the

ERSeGEL 2024 - Workshop on Extended Reality and Serious Games for Education and Learning

708

Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial

Information Sciences, XLII-2/W3, 425-431. https://

doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-xlii-2-w3-425-2017

Lim, K.Y.T. and Lim, R. (2020). Semiotics, memory and

augmented reality: History education with learner-

generated augmentation. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 51(3), 673-691. https://doi.org/10.1111/

bjet.12904

Liu, H., & Wong, S.-K. (2004). Singapore Chinese Society

in Transition: Business, Politics, and Socio-Economic

Change. New York: Peter Lang Pub.

Lucardie, D. (2014). The impact of fun and enjoyment on

adult’s learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 142, 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbsp

ro.2014.07.696

Manuel, P.-C. V., José, P.-C. I., Manuel, F.-M., Iván, M.-

O., & Baltasar, F.-M. (2019). Simplifying the Creation

of Adventure Serious Games with Educational-

Oriented Features. Journal of Educational Technology

& Society, 22(3), 32–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/

26896708

Olson, R., & Wagler, M. (2011). Afield in Wisconsin:

Cultural Tours, Mobile Learning, and Place-based

Games. Western Folklore, 70(3/4), 287–309.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/24551260

Othman, M. K., Aman, S., Anuar, N. N., & Ahmad, I.

(2021). Improving Children's Cultural Heritage

Experience Using Game-based Learning at a Living

Museum. Journal on Computing and Cultural

Heritage, 14(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1145/345

3073

Ryan, R. M., Rigby, C. S., & Przybylski, A. (2006). The

motivational pull of video games: A self-determination

theory approach. Motivation and Emotion, 30(4), 344–

360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8

Schiefele, U. (2009). Situational and Individual Interest. In

K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of

Motivation at School (pp. 197-222). Routledge/Taylor

& Francis Group.

Sim, C. (n.d.). Special Assistance Plan schools. Singapore

Infopedia. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?

cmsuuid=9648a15d-33a3-4622-b91b-12aec4fe7ee2

Smith, G. A., & Sobel, D. (2010). Place- and Community-

Based Education in Schools. New York: Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203858530

Volkmar, G., Wenig, N., & Malaka, R. (2018). Memorial

Quest - a location-based serious game for Cultural

Heritage Preservation. Proceedings of the 2018 Annual

Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play

Companion Extended Abstracts. https://doi.org/

10.1145/3270316.3271517

Whitton, N. (2012). Games-Based Learning. In: Seel, N.M.

(Eds.) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning (pp.

1337-1340). Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/

10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_437

Ying, O. L., Hipiny, I., Ujir, H. and Samson Juan, S. F,

(2021). Game-based Learning using Augmented

Reality. 2021 8th International Conference on

Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE),

344-348. doi: 10.1109/ICCCE50029.2021.9467187

Yun, H. (2023). Combining Cultural Heritage and Gaming

Experiences: Enhancing Location-Based Games for

Generation Z. Sustainability, 15(18), 13777.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813777

APPENDIX A

Table 1: Table showing thematic analysis of qualitative

feedback from participants, who are represented as the

letter P and are numbered from P1 to P10 for anonymity.

Strengths

Content

(Presentation)

● P2: “I like the positive, funny

narration.”

● P3: “Cute and interactive”

● P5, P7: “The dialogue”

● P8: “Uses various forms (eg

videos, 3D models) to teach

concepts

Content (Plot) ● P1: “Very interesting plot.”

● P9: “the trail was meaningful and

the storyline was coherent”

Game

Mechanics

● P10: “info we can actually find

instead of guessing randomly”

● P6: “it was a new way to explore

the school”

● P4: “It’s quite easy to play”

External

Factors

Limitations

Content

(Presentation)

● P1: “it wasn’t narrated out loud.

It would have been more

interactive if it [was]”

● P4: “The dialogues could be a bit

longer”

● P5: “few dialogue”

Content (Plot) ● P8: “No branching storyline”

● P6: “Could have been to more

secluded places that we usually

don’t go to”

Game

Mechanics

● P7: “The fact that I had to walk”

● P3, P9, P10: Laggy GPS

External

Factors

● P2: “the thing is I don’t like the

topic [on the school]”

The Preservation of Heritage in a School Campus with Augmented Reality (AR) and Game-Based Learning

709

APPENDIX B

This study involves the use of the Situational Interest

Scale proposed by Chen, Darst & Pangrazi (1999).

The Situational Interest Scale includes 5

dimensions: Exploration Intention, Instant

Enjoyment, Attention Demand, Challenge and

Novelty, excluding Total Interest. There are 4 items

per dimension, and 4 items for Total Interest, making

up a total of 24 items. Revisions were made to the

Exploration Intention dimension to fit the context of

the study without changing the original meaning of

the statements.

Participants were required to rate each statement

on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very untrue) to 5

(very true). Statements were randomly placed in the

questionnaire completed by participants.

__________________________________________

Exploration Intention (original):

● I want to discover all the tricks in this

activity.

● I want to analyze it to have a grasp on it.

● I like to find out more about how to do it.

● I like to inquire into details of how to do it.

Revised statements to adapt to the context of the study

(AR game-based learning):

● I want to discover all the information that

was in the game.

● I want to study the information in the game

in detail to have a grasp on it.

● I like to find out more about the information

given in the game.

● I like to inquire into the details of the

information in the game.

__________________________________________

Instant Enjoyment:

● It is an enjoyable activity to me.

● This activity is exciting.

● The activity inspires me to participate.

● This activity is appealing to me.

__________________________________________

Attention Demand:

● My attention was high.

● I was very attentive all the time.

● I was focused.

● I was concentrated.

__________________________________________

Challenge:

● It is a complex activity.

● This activity is a demanding task.

● This activity is complicated.

● It is hard for me to do this activity.

__________________________________________

Novelty:

● This activity is new to me.

●

This activity is fresh.

● This is a new-fashioned activity for me to

do.

● This is an exceptional activity.

__________________________________________

Total Interest:

● This activity is interesting.

● This activity looks fun to me.

● It is fun for me to try this activity.

● This is an interesting activity for me to do.

__________________________________________

Cronbach’s a: .78, .80, .90, .91, .90 for above

dimensions respectively.

ERSeGEL 2024 - Workshop on Extended Reality and Serious Games for Education and Learning

710