Development of a Patient-Embodied Experience, How and Why?

Krista Hoek

a

, Monique van Velzen

b

and Elise Sarton

c

Department of Anaesthesiology, LUMC, Albinusdreef 2, 2333ZA, Leiden, The Netherlands

Keywords: VR, Therapeutic Language and Communication, Ethnographic Phenomenology, Health Care Education,

Patient-Embodied Experience, Proteus-Effect.

Abstract: Introduction: The rise of immersive technologies, particularly virtual reality (VR), has significantly impacted

medical education. In patient-embodied VR, through VR headsets, learners can embody patient's perspective,

offering a secure and immersive learning encounter. This communication outlines a framework for crafting

patient-embodied experiences, drawing from our VR endeavours aimed at enhancing therapeutic

communication skills in medical education. Methods: Our framework includes a development process with

consideration of user experience, technical implementation, content creation and validation. Central to content

creation is the collaborative construction of a patient journey, involving the involved parties via storyboards

and scripts distinguishing direct and indirect actions. Results: For our patient-embodied experience, the

cooperative development of the patient journey, script and storyboard included an initial version created by

the main researcher after study of landmark articles on therapeutic communication and fieldwork. Validation

was achieved through two group sessions with healthcare providers who consented to participate.

Conclusions and practice implications: The findings and insights presented can contribute to the growing

knowledge in the field of educational VR development. They demonstrate the feasibility and potential of

leveraging immersive technologies to create engaging and impactful virtual experiences. Hitherto, further

validation may evaluate how they influence believes and attitudes of healthcare providers towards therapeutic

communication.

1 INTRODUCTION

Medical education has been incorporating elements

of experiential learning for several decades, and the

specific use of immersive technologies has gained

more prominence in recent years. In particular,

learning with virtual reality (VR), or immersive

virtual environments (IVEs) aligns with the

Constructivist Theory, which suggests that learners

actively construct their knowledge and understanding

of the world by building upon their existing mental

frameworks. In an immersive learning environment,

learners are given the opportunity to explore,

discover, and make meaning from their experiences

(Whitman, 1993)

In virtual reality (VR), immersive learning

incorporates various sensory modalities to enhance

multisensory engagement enabling embodiment.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1984-3182

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0289-6432

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-4403-3815

Embodiment is the possibility in VR to visually

substitute a person's real body by a life-sized virtual

one, seen from the person's own first-person

perspective. In other words, when we place a VR

headset on, our virtual bodies momentarily substitute

our real bodies, a phenomenon known as the Proteus

effect (Fox et al., 2013). Multisensory and motor

systems interconnect during cognitive processing.

During VR, embodiment can increase users’

engagement and provide emotional fidelity invoking

a sense of presence creating realistic emotional and

neurocognitive responses (Bem, 1972; Navarro et al.,

2022).

When using VR as educational tool, learners have

the ability to experience a full 360-degree view,

providing them with unrestricted access and freedom

to explore their surroundings. This contrasts to

traditional video experiences, where the audience's

perspective is limited to a fixed viewpoint as depicted

758

Hoek, K., van Velzen, M. and Sarton, E.

Development of a Patient-Embodied Experience, How and Why?.

DOI: 10.5220/0012755800003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 758-764

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

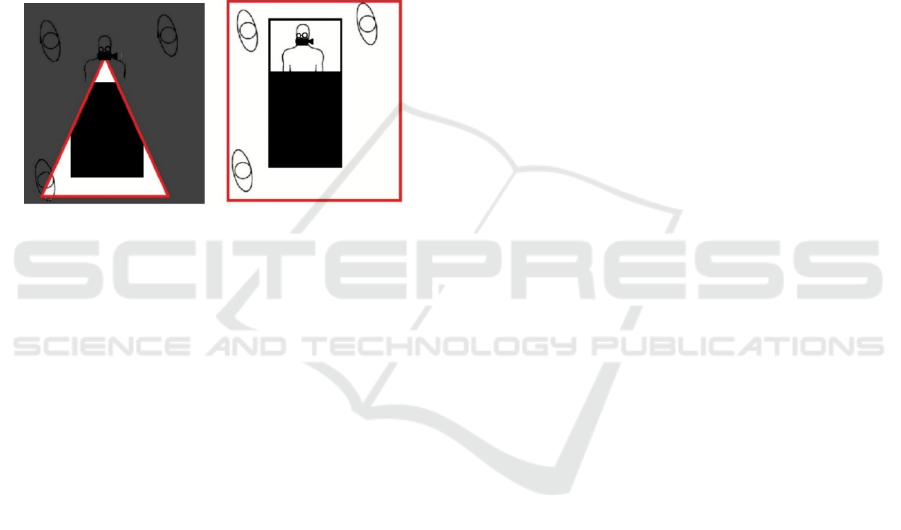

in Figure 1. The distinctive aspect of VR lies in its

participatory nature. In VR, writers, directors, and

producers, referred to as builders, do not have the

ability to dictate how learners engage with the story.

Instead, they can only invite participation, allowing

learners to choose where to direct their attention and

which aspects of the story to focus on (O’Sullivan et

al., 2018). This stands in contrast to conventional

storytelling, where a storyteller transmits the

narrative to listeners. Traditional videos typically

provide viewers a fixed perspective. The screen acts

as a window into the world of the video, and viewers

can only observe the events and scenes from the

specific viewpoint chosen by the director as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Red outlines show the extent of what a camera can

film in 90 vs 360 degrees of freedom. Left: 90 degrees of

freedom of traditional film, Right: 360 degrees of freedom

of VR.

In healthcare, a growing emphasis on patient-

centered care, and consumerism in medicine has

exemplified the importance of effective physician-

patient communication (Santana et al., 2018) and the

use of IVEs as an educational tool in this context

(“The Effects of Viewing an Uplifting 360-Degree

Video on Emotional Well-Being Among Elderly

Adults and College Students Under Immersive

Virtual Reality and Smartphone Conditions,” 2020;

Tang et al., 2022). We will refer to patient-embodied

VR as the specific VR application where a learner

who puts on the VR headset virtually becomes the

patient. Given that this immersive transformation has

the capacity to affect self-perception, attitudes,

convictions, and conduct in both implicit and explicit

ways (Bian et al., 2015; Fox et al., 2013; Navarro et

al., 2022), our hypothesis posits that it holds

substantial promise as an exceedingly effective and

innovative pedagogical approach in education on

communication skills.

An example of the use of patient-embodied VR

can be found in our work published recently (Hoek et

al., 2023a, 2023b). We developed two patient-

embodied experiences to create a possibility for

healthcare providers to feel what it is like to become

a patient. In these VR experiences, the learner

experiences the sequential stages of a patient

undergoing elective general anesthesia and surgery,

with nuanced shifts in language and interactions. We

will describe how we have developed these

experiences, and what important lessons we have

learned that can be used by researchers aiming to

develop-embodied VR experiences.

2 METHODS

This prospective exploratory research was carried out

at the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC,

Leiden, the Netherlands), a large tertiary academic

teaching hospital. The protocol was approved by the

Institutional Science Committee and obtained a

waiver from the Institutional Review Board

(NWMO-LUMC).

Informed consent was obtained prior to

inclusion, participation was voluntary and privacy

rights were in alignment with the Declaration of

Helsinki and GDPR guidelines. Data was collected

and recorded between February 2019 to December

2020. Participants received no financial

compensation.

2.1 Participants and Procedures

Healthcare providers working in the OR were invited

to participate in the development of the patient-

embodied VR experiences. They were recruited

between January 2019 and May 2019. The procedure

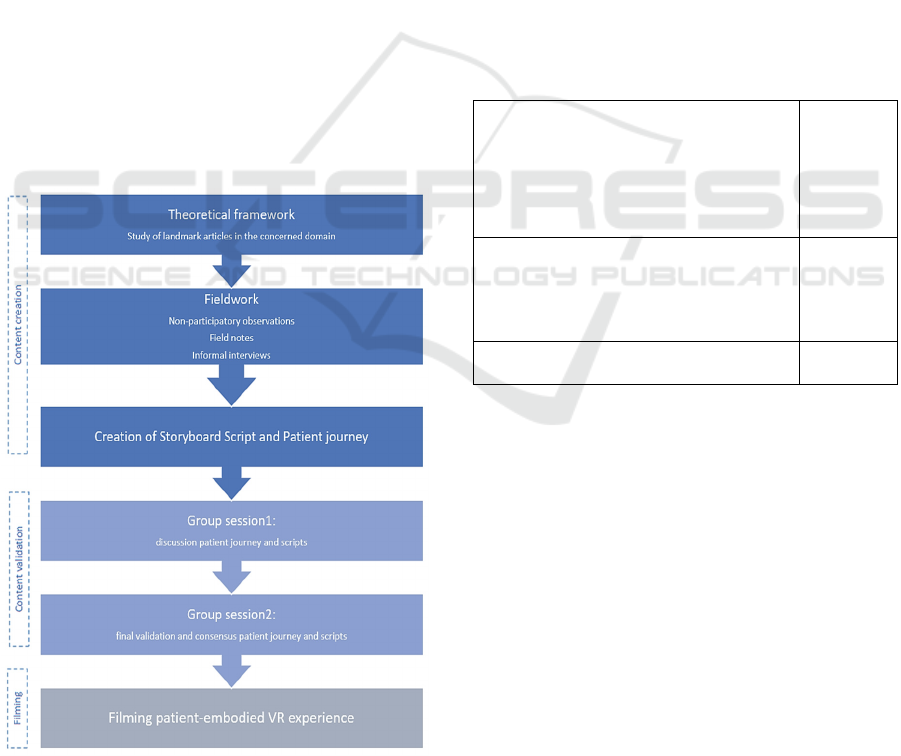

encompassed content creation, content validation,

and filming and editing of the VR experiences as

shown in Figure 2.

2.2 Content Creation

To create the storyboard and script of the patient

journey, a theoretical framework needed to consider

the study of landmark articles in the concerned

domain. In our case, Landmark patient-centered

studies were used to include important aspects of

lived patient experiences in preoperative settings

(Ben-Amitay et al., 2006; Butt, 2021; Derksen et al.,

2013; Kain et al., 2004; Kain et al., 2006; Lang et al.,

2005; Maranets & Kain, 1999; Smith & Mishra, 2010;

Swayden et al., 2012).

Secondly, fieldwork of the researcher (KH)

included informal interviews with healthcare

providers and patients, along with observations to

gather data was used to create an initial script for the

patient journeys as shown in Figure 2.

Development of a Patient-Embodied Experience, How and Why?

759

2.3 Content Validation

Group sessions are an adapted tool to validate the

storyboard and script (Stewart et al., 2007). In our

study, a first group session was held to discuss and

adapt the scripts.

Group input such as photographs, focused and

selective observation notes, reflective notes and

commentaries were used to write a second version of

the patient journeys. A second group session implied

a final validation where the scripts were discussed

and adapted until consensus was reached; that is until

the final script was consented by all group members

(Briggs et al., 2005) as shown in Figure 2.

The specific linguistic features were further

validated by an independent hypnotherapist based on

validated and relevant research (Boselli et al., 2018;

Lang, 2019; Lang & Berbaum, 1997; Lang et al.,

2005; Swayden et al., 2012; Watzlawick, 1978; Zech

et al., 2014).

2.4 Filming and Editing

Asking healthcare providers to play their own role has

several advantages as its economical, and the actors

may identify themselves very easily with their own

Figure 2 structure of the study participation.

professional role. We asked the developers to play

their own professional role, e.g. a surgeon would play

the surgeon. An anaesthetic nurse volunteered to play

the patient, as she had been a surgical patient several

times before.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Case Study Description

Nine healthcare providers participated in the

development of the patient-embodied VR

experiences. Six were OR nurses , one was a surgeon

and two were anaesthesiologist-hypnotherapists. One

hypnotherapist who was not affiliated with our

hospital did not participate in the filming of the

experiences. The majority was female (82%).

Demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the VR

development team and study participants.

Clinical role

Anaesthesiologist-hypnotherapist

CRNA (Nurse anaesthetist)

Preoperative holding area nurse

Operating room nurse

Surgeon

2

2

3

1

1

Years of practice

<1year

1-5years

5-10years

>10years

1

3

1

4

Sex

Male/Female

2/7

3.2 Development of the

Patient-Embodied VR Experiences

Between February 2019 and December 2019 two

scripts and storyboards were created: the positive and

negative patient-embodied VR experience.

Guidelines of several digital platforms were used

(Newton, 2016; O’Sullivan et al., 2018). Filming was

performed using a GoPro

®

camera, editing was

performed using Movavi

®

enabling the experiences

to be available on most common VR headsets. Also,

an online Youtube version was uploaded making it

possible to view the experience online.

The final durations of the experiences were 12

minutes and 19 seconds for the negative experience,

and 10 minutes and 36 seconds for the positive

experience.

ERSeGEL 2024 - Workshop on Extended Reality and Serious Games for Education and Learning

760

The story-world needed to be as consistent with

reality as possible, using objects, personas, and

actions to stimulate the sense of immersive presence.

3.2.1 Storyboard and Script

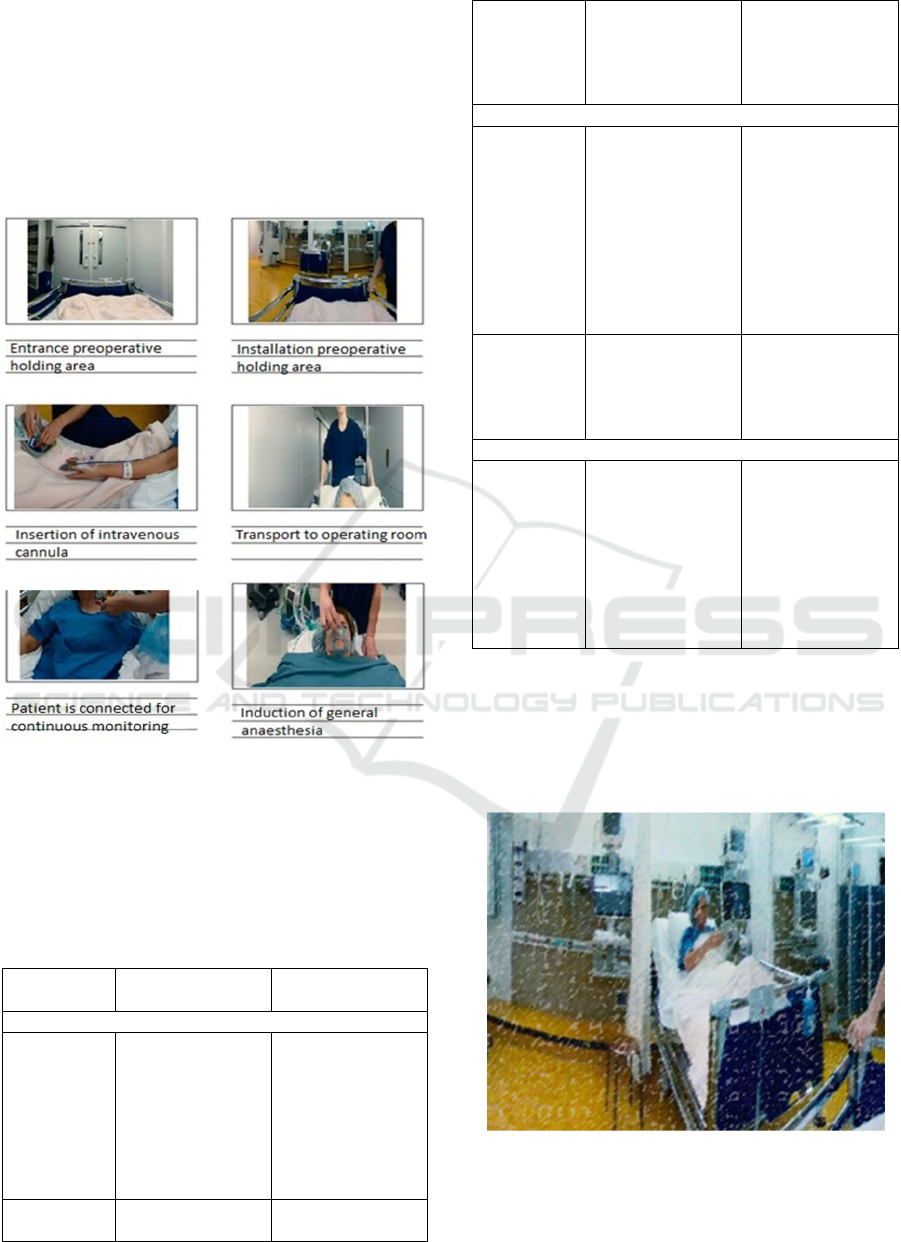

We developed a storyboard with the main scenes as

shown in Figure 3 including all direct interactions

with the patient.

Figure 3: Storyboard patient-embodied VR experience.

We developed a script with ‘shadow actions’ visible

if the learner would look around. An overview of the

main differences in setting, direct interactions and

shadow actions can be found in Table 2.

Table 2: Overview of main difference in setting,

interactions and shadow actions.

Negative

experience

Positive experience

Setting

Preoperative

holding area

No (distraction)

activities for other

patients

No preventive

measures for

delirium prevention

Other patients use a

tablet or read a

magazine

Curtains opened,

visible clock,

noises of

monitoring

minimalized

Operation

room

Radio on Noises minimalized

Alarms and sounds

of continuous

monitoring on.

Surgical equipment

partially displayed

No visible surgical

equipment

Direct interactions

Contact with

preoperative

holding area

-Patient is ignored

when she requests

to go to the toilet

-Nurse does not ask

any personal

questions while she

places the IV

cannula

-Nurse sits next to

the patient

-Nurse uses

hypnotic distraction

methods during the

placement of the IV

cannula

-Nurse responds to

the concerns of the

patient.

Contact with

anaesthesio-

logist

Contact with

anaesthesiologist

with little rapport.

Anaesthesiologist

asks personal

questions before the

patient is taken into

the OR

Shadow interactions

Preoperative

holding area

OR nurse passes as

the patient is

brought to the

preoperative

holding area, he

tells his colleague

there is a bleeding

in the OR, and he

needs to hurry

OR nurse passes as

the patient is

brought to the

preoperative

holding area. He

holds something in

his arms, but is

discrete.

3.2.2 Setting

In the positive experience, another patient present is

able to read a magazine as shown in Figure 4. This is

a distraction method that may increase comfort while

the patients await their surgery (Pati & Nanda, 2011).

Figure 4: Positive experience: another patient reads a

magazine.

Development of a Patient-Embodied Experience, How and Why?

761

3.2.3 Direct Interactions

There are changes in attitude of the health care

providers with or without a direct therapeutic

relationship. One example is the communication style

of the anaesthesiologist just before the start of the

inductive phase of anaesthesia (patient is induced into

a state of unconsciousness and analgesia (pain relief)

before the start of the surgical procedure) as shown in

Figure 5.

In the negative video, the anaesthesiologist

administers the medication, however, the

communication shows limited effort to establish

rapport (Butt, 2021; Hall et al., 1995; Hoek et al.,

2023a). Furthermore, the potential side effects of the

drugs are explicitly mentioned, thereby increasing the

likelihood of the patient experiencing these adverse

effects (Lang et al., 2005; Zech et al., 2014).

In the positive experience, the anaesthesiologist

uses hypnotic linguistic techniques to induce

relaxation (Boselli et al., 2018), enhance focus and

promote a smooth start of general anaesthesia. The

anaesthesiologist sits beside the patient (Swayden et

al., 2012).

Figure 5: Anaesthesiologist sits next to the patient, uses

suggestive language to induce relaxation.

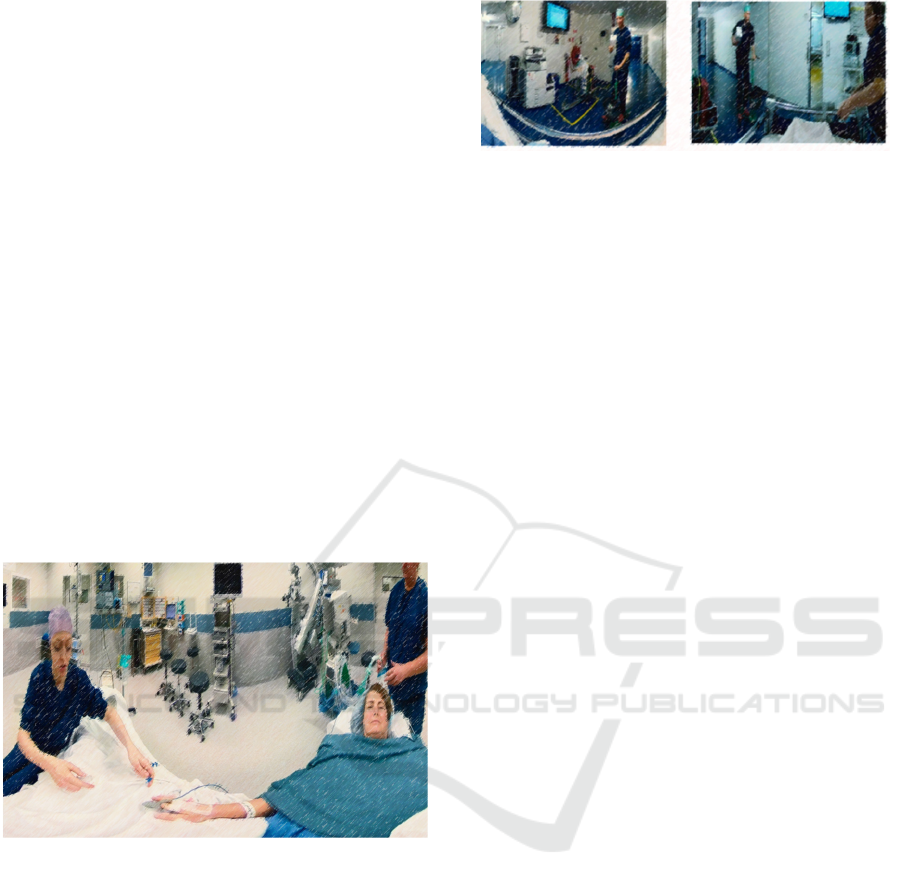

3.2.4 Shadow Actions

An example of a suggestion used in the final script

was having an OR-nurse pass by to bring blood for

the transfusion of another patient to enhance

authenticity of the dynamics of the operating theatre.

Subtle changes between the experiences are shown in

Figure 6.

One portrays an OR-nurse that politely smiles to

the patients without showing any concerns. The other

portrays an OR-nurse that expresses a sense of

urgency. He seems bothered, and tells the

preoperative nurse he has to deliver blood. The

preoperative nurse seems worried.

Figure 6: Left: the operating room (OR) nurse remains

silent and smiles politely without showing his concerns.

Right: the OR nurse conveys a sense of urgency to bring

blood to another patient, and the preoperative nurse appears

annoyed and worried.

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

4.1 Discussion

This study describes the development of two patient-

embodied VR experiences. The specific linguistic

features were validated by an independent

hypnotherapist and were based on validated and

relevant research (Boselli et al., 2018; Lang, 2019;

Lang & Berbaum, 1997; Lang et al., 2005; Swayden

et al., 2012; Watzlawick, 1978; Zech et al., 2014).

Internal validity of the VR experiences was

confirmed given that healthcare providers

participated in the development of these experiences

themselves. Between the two experiences, small

changes in setting, interactions and shadow actions

would implicitly suggest a more or less welcoming

experience. Indeed, the development included

addition of these several elements enhancing

authenticity of the VR experiences.

This type of immersive storytelling with VR

offers for learners a possibility to create their own

story in 360°; as they were able to look around freely

in VR. Additionally, healthcare providers played their

own roles during the filming of the scenes.

4.2 Limitations

One of the limitations of the VR experiences lies in

the limited interaction within the VR-environment.

The learner had the ability to observe their

surroundings; however, due to the recorded nature of

the experiences, learners were not able to freely move

around as they would have in a virtual environment

utilizing computer-generated 3D video imagery.

We selected this setting based on the believe that

a patient typically finds themselves confined to a

hospital bed with limited mobility or free choices. We

contend that utilizing a genuine operating theatre and

ERSeGEL 2024 - Workshop on Extended Reality and Serious Games for Education and Learning

762

real actors enhances fidelity, thereby intensifying the

sense of immersion.

4.3 Innovation

The findings and insights presented in this study can

contribute to the growing knowledge in the field of

educational VR development. They demonstrate the

feasibility and potential of leveraging immersive

technologies to create engaging, authentic and

impactful virtual experiences (Hoek et al., 2023a)

4.4 Conclusion

By using immersive VR technology, one can create

an interactive and engaging virtual environment that

allows learners to experience a simulated reality, that

is the experience of being a patient.

This development process involves careful

consideration of user experience, technical

implementation, content creation and validation. In

our opinion, key elements of the content creation

should be based on the cooperative development of a

patient journey, with participation of the involved

parties using a storyboard and script that distinguishes

between direct actions and indirect (shadow) actions.

4.5 Future Directions and Study

Validation

The findings of this study can contribute to further

research and healthcare education programs avid to

use experiential learning with patient-embodied VR.

We conclude with a call for further research to fully

unlock the potential and drawbacks of patient-

embodied VR as an educational tool and its

usefulness in medical training. Also, further research

may examine how patient-embodied VR might affect

patient reported outcomes like preoperative anxiety.

Initial validation of our patient-embodied

experience consisted of a qualitative study analyzing

the lived experience of anaesthesiologists (Hoek et

al., 2023a). Further validation may include evaluation

of the effects of the implementation of a training in

therapeutic communication with an integrated

patient-embodied VR experience.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all healthcare providers participating in the

development of the VR experiences.

COMPETING INTERESTS

This research did not receive any specific grant from

funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-

for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

Bem, D. (1972). Self-perception theory (Vol. 6). Academic

Press.

Ben-Amitay, G., Kosov, I., Reiss, A., Toren, P., Yoran-

Hegesh, R., Kotler, M., & Mozes, T. (2006). Is elective

surgery traumatic for children and their parents? J

Paediatr Child Health, 42(10), 618-624.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00938.x

Bian, Y., Zhou, C., Tian, Y., Wang, P., & Gao, F. (2015).

The Proteus Effect: Influence of Avatar Appearance on

Social Interaction in Virtual Environments. HCI,

Boselli, E., Musellec, H., Bernard, F., Guillou, N., Hugot,

P., Augris-Mathieu, C., Diot-Junique, N., Bouvet, L., &

Allaouchiche, B. (2018). Effects of conversational

hypnosis on relative parasympathic tone and patient

comfort during axillary brachial plexus blocks for

ambulatory upper limb surgery: A Quasiexperimental

Pilot Study. Int J Clin Exp Hypn, 66(2), 134-146.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2018.1421355

Briggs, R., Kolfschoten, G., & de Vreede, G.-J. (2005).

Toward a Theoretical Model of Consensus Building.

Butt, M. F. (2021). Approaches to building rapport with

patients. Clinical Medicine, 21(6), e662-e663.

https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2021-0264

Derksen, F., Bensing, J., & Lagro-Janssen, A. (2013).

Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a

systematic review. Br J Gen Pract, 63(606), e76-84.

https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X660814

Fox, J., Bailenson, J., & Tricase, L. (2013). The

embodiment of sexualized virtual selves: The Proteus

effect and experiences of self-objectification via

avatars. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 930–938.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.027

Hall, J. A., Harrigan, J. A., & Rosenthal, R. (1995).

Nonverbal behavior in clinician—patient interaction.

Applied and Preventive Psychology, 4(1), 21-37.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-

1849(05)80049-6

Hoek, K., van Velzen, M., & Sarton, E. (2023a). Patient-

embodied virtual reality as a learning tool for

therapeutic communication skills among

anaesthesiologists: A phenomenological study. Patient

Education and Counseling, 114, 107789. https://doi.org/

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2023.107789

Hoek, K., van Velzen, M., & Sarton, E. (2023b). Response

to correspondance on patient-embodied virtual reality

as a learning tool for therapeutic communication skills

among anaesthesiologists: A phenomenological study.

Patient Educ Couns, 117, 107980. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.pec.2023.107980

Development of a Patient-Embodied Experience, How and Why?

763

Kain, Z. N., Caldwell-Andrews, A. A., Maranets, I.,

McClain, B., Gaal, D., Mayes, L. C., Feng, R., &

Zhang, H. (2004). Preoperative anxiety and emergence

delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviors.

Anesth Analg, 99(6), 1648-1654. https://doi.org/10.12

13/01.Ane.0000136471.36680.97

Kain, Z. N., Mayes, L. C., Caldwell-Andrews, A. A., Karas,

D. E., & McClain, B. C. (2006). Preoperative anxiety,

postoperative pain, and behavioral recovery in young

children undergoing surgery. Pediatrics, 118(2), 651-

658. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2920

Lang, E. (2019). Comfort Talk®: From the Waiting Room

to the Treatment Suite. Dtsch Z Zahnarztl Hypn, 25(1),

22-24.

Lang, E. V., & Berbaum, K. S. (1997). Educating

interventional radiology personnel in nonpharmaco-

logic analgesia: effect on patients' pain perception.

Acad Radiol, 4(11), 753-757. https://doi.org/10.1016/

s1076-6332(97)80079-7

Lang, E. V., Hatsiopoulou, O., Koch, T., Berbaum, K.,

Lutgendorf, S., Kettenmann, E., Logan, H., &

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2005). Can words hurt? Patient-

provider interactions during invasive procedures. Pain,

114(1-2), 303-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.200

4.12.028

Maranets, I., & Kain, Z. N. (1999). Preoperative anxiety

and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth

Analg, 89(6), 1346-1351. https://doi.org/10.1097/

00000539-199912000-00003

Navarro, J., Peña, J., Cebolla, A., & Baños, R. (2022). Can

Avatar Appearance Influence Physical Activity? User-

Avatar Similarity and Proteus Effects on Cardiac

Frequency and Step Counts. Health Commun, 37(2),

222-229. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1834

194

Newton, K. (2016). The Storyteller’s Guide to the Virtual

Reality Audience. Stanford d.school. https://medium.

com/stanford-d-school/the-storyteller-s-guide-to-the-

virtual-reality-audience-19e92da57497

O’Sullivan, B., Alam, F., & Matava, C. (2018). Creating

Low-Cost 360-Degree Virtual Reality Videos for

Hospitals: A Technical Paper on the Dos and Don’ts

[Tutorial]. J Med Internet Res, 20(7), e239.

https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9596

Pati, D., & Nanda, U. (2011). Influence of positive

distractions on children in two clinic waiting areas.

Herd, 4(3), 124-140. https://doi.org/10.1177/19375

8671100400310

Santana, M. J., Manalili, K., Jolley, R. J., Zelinsky, S.,

Quan, H., & Lu, M. (2018). How to practice person-

centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expect,

21

(2), 429-440. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12640

Smith, A. F., & Mishra, K. (2010). Interaction between

anaesthetists, their patients, and the anaesthesia team.

Br J Anaesth, 105(1), 60-68. https://doi.org/10.1093/

bja/aeq132

Stewart, D., Shamdasani, P., & Rook, D. (2007). Focus

Groups (2nd ed.) https://doi.org/10.4135/97814129

91841

Swayden, K. J., Anderson, K. K., Connelly, L. M., Moran,

J. S., McMahon, J. K., & Arnold, P. M. (2012). Effect

of sitting vs. standing on perception of provider time at

bedside: a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns, 86(2), 166-

171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.024

Watzlawick, P. (1978). The language of change: Elements

of therapeutic communication. W W Norton & Co.

Whitman, N. (1993). A review of constructivism:

understanding and using a relatively new theory. Fam

Med, 25(8), 517-521.

Zech, N., Seemann, M., & Hansen, E. (2014). [Nocebo

effects and negative suggestion in anesthesia].

Anaesthesist, 63(11), 816-824. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s00101-014-2386-8

ERSeGEL 2024 - Workshop on Extended Reality and Serious Games for Education and Learning

764