Perception of Privacy Tools for Social Media: A Qualitative Analysis

Among Japanese

Vanessa Bracamonte

1

, Yohko Orito

2

, Yasunori Fukuta

3

, Kiyoshi Murata

3

and Takamasa Isohara

1

1

KDDI Research, Inc., Saitama, Japan

2

Faculty of Collaborative Regional Innovation, Ehime University, Ehime, Japan

3

School of Commerce and Centre for Business Information Ethics, Meiji University, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords:

Privacy Concern, Privacy Tools, Social Media, User Study.

Abstract:

Social media platforms are used worldwide, and privacy risks are encountered by all users regardless of coun-

try. Therefore, privacy-enhancing tools that automatically detect relevant information in a users’ post could

be useful globally, but perception of such tools has not been widely investigated. To address this issue, we

conducted a qualitative analysis of perception in Japan, where there is high social media use, to understand

what are users’ opinions and privacy concerns towards this type of privacy tools. We find that Japanese users’

perception of privacy tool appears to be influenced by an overall sense of distrust towards apps and developers

and by general privacy concerns. On the other hand, specific privacy concerns due to the nature of the privacy

tool are less frequent, and there were not marked differences in perception when compared to concerns towards

a non-privacy tool. The findings suggest that the acceptance of privacy tools in Japan would be influenced by

the general sense of anxiety for privacy.

1 INTRODUCTION

In social media platforms, users post information that

they may not realize reveals personal details about

themselves or others. Later, the users might regret re-

vealing their private information and may suffer con-

sequences from this unconscious sharing (Wang et al.,

2011; Mao et al., 2011; Sleeper et al., 2013).

To help avoid the unintentional reveal of personal

information, there have been proposals of privacy-

enhancing tools which automatically recognize when

private information is being disclosed, alert the user

and anonymize the content involved (Caliskan Islam

et al., 2014; Tesfay et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Guar-

ino et al., 2022). Studies conducted among USA so-

cial media users have shown that such tools are con-

sidered useful for privacy protection, but at the same

time they appear to bring forth concerns about the se-

curity and privacy risks of the tool itself (Bracamonte

et al., 2021).

Many social media platforms are used by users

from all over the world and consequently the solu-

tions provided for privacy protection would be help-

ful for all users. However, users from different coun-

tries can have different concerns related to informa-

tion privacy (Lowry et al., 2011), and these differ-

ences might be reflected on their opinion and accep-

tance of privacy-enhancing tools.

In this paper, we conduct a qualitative analysis

to understand the perception of Japanese social me-

dia users towards privacy tools, focusing on privacy-

related issues and concerns. Specifically, we address

the following research questions:

• Do opinions of the privacy tools include aware-

ness of privacy-related issues?

• What are the reasons for the perception of privacy

concern towards privacy tools?

• Are the responses related to a privacy tool qualita-

tively different from those related to a non-privacy

tool?

To answer these questions, we qualitatively ana-

lyzed the responses of 505 participants to open-ended

questions on their opinion and privacy concerns to-

wards an hypothetical tool for social media content.

The hypothetical tool corresponded to one of four

groups consisting of a combination of the factors of

type of tool (Privacy and Non-privacy) and the type

of data the tool analyzed (Image or Text).

The findings show that themes related to privacy

awareness, such as the value of privacy protection

and concern for surveillance, can be identified among

Bracamonte, V., Orito, Y., Fukuta, Y., Murata, K. and Isohara, T.

Perception of Privacy Tools for Social Media: A Qualitative Analysis Among Japanese.

DOI: 10.5220/0012762000003767

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT 2024), pages 151-162

ISBN: 978-989-758-709-2; ISSN: 2184-7711

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

151

the Japanese respondents’ opinions towards the pri-

vacy tool. And distrust towards apps and develop-

ers, as well as general privacy concern, were iden-

tified as themes that appeared frequently in the rea-

sons for privacy concerns towards the privacy tools.

On the other hand, specific privacy concerns reasons,

with the exception of data collection, were less fre-

quent overall. In addition, we did not identify marked

qualitative differences between the responses of par-

ticipants who viewed a privacy tool compared to those

who viewed a non-privacy tool. These findings con-

tribute to a wider understanding of the challenges for

the design of privacy-enhancing tools for social media

in other contexts.

2 RELATED WORK

Users encounter problems and have regrets brought

on by revealing too much information on social media

sites (Sleeper et al., 2013). Users can leak informa-

tion through text and images, and research has pro-

posed ways to detect that information and alert the

user. For example, (Tesfay et al., 2019) developed a

tool that analyzed Twitter data to detect and catego-

rize privacy sensitive information included in users’

tweets. (Li et al., 2019) proposed a system which

made use of bystander detection and face matching

techniques to to detect and hide users in photos. These

automated tools require some level of access to pri-

vate information to be able to provide privacy pro-

tections, and therefore can themselves be the target

of privacy concerns. (Bracamonte et al., 2021) con-

ducted a user study on perception of this type of pri-

vacy tools and found that worries about privacy were

mentioned more frequently than usefulness or perfor-

mance aspects. Follow-up work also reported that

there was a higher level of surveillance concern to-

wards privacy tools than towards tools that behaved

similarly but were not for privacy (Bracamonte et al.,

2022).

These studies have been conducted with partici-

pants in English-speaking countries such as USA and

Canada, but social media platforms are used all over

the world. In Japan, social media and social network-

ing services are widely used by people from all demo-

graphics, with the number of social media users esti-

mated to be around 105.8 million in 2023 (Statista,

2023). While social media sites have gained popu-

larity in Japanese society, this has also resulted in so-

cial problems due to the inappropriate dissemination

of personal information and leakage of private infor-

mation, and the government has cautioned against be-

havior such as sharing photos that include location in-

formation (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Commu-

nications (Japan), 2023).

According to the results of surveys on Japanese

online services users’ attitudes towards privacy and

towards personal data protection (Murata and Orito,

2013; Murata et al., 2014; Orito et al., 2013; Orito

and Murata, 2014), many users recognize the impor-

tance of privacy protection. On the other hand, the re-

search also found that privacy attitudes can depend on

the context, and Japanese users were not so concerned

about privacy policies and privacy seals when using

social media and online shopping sites (Orito et al.,

2013), and had limited understanding of the business

models of companies that acquire, store, share and

use personal information (Orito and Murata, 2014),

as well as of the concept of privacy itself. Earlier

research (Adams et al., 2011) has reported that on

Japanese social media sites such as Mixi, users re-

frained from disclosing private information, so there

is the possibility of a change in attitudes due to the

type of platform or due to the users themselves. These

studies suggest that although Japanese users are aware

of the importance of privacy protection, their actual

usage may not reflect adequate approaches and prac-

tical behaviors for the protection of privacy.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Survey Design

We prepared a survey in which participants were

shown a tool description and interface, and then were

asked to give their opinion about it. Participants were

assigned to one of four groups, randomly, and the

groups were defined by the combination of the fac-

tor of type of tool (Privacy or Non-privacy) and the

data analyzed by the tool (Image or Text). The sur-

vey design and tool interfaces were adapted for the

Japanese participants from (Bracamonte et al., 2022).

The translation process is explained in the next sec-

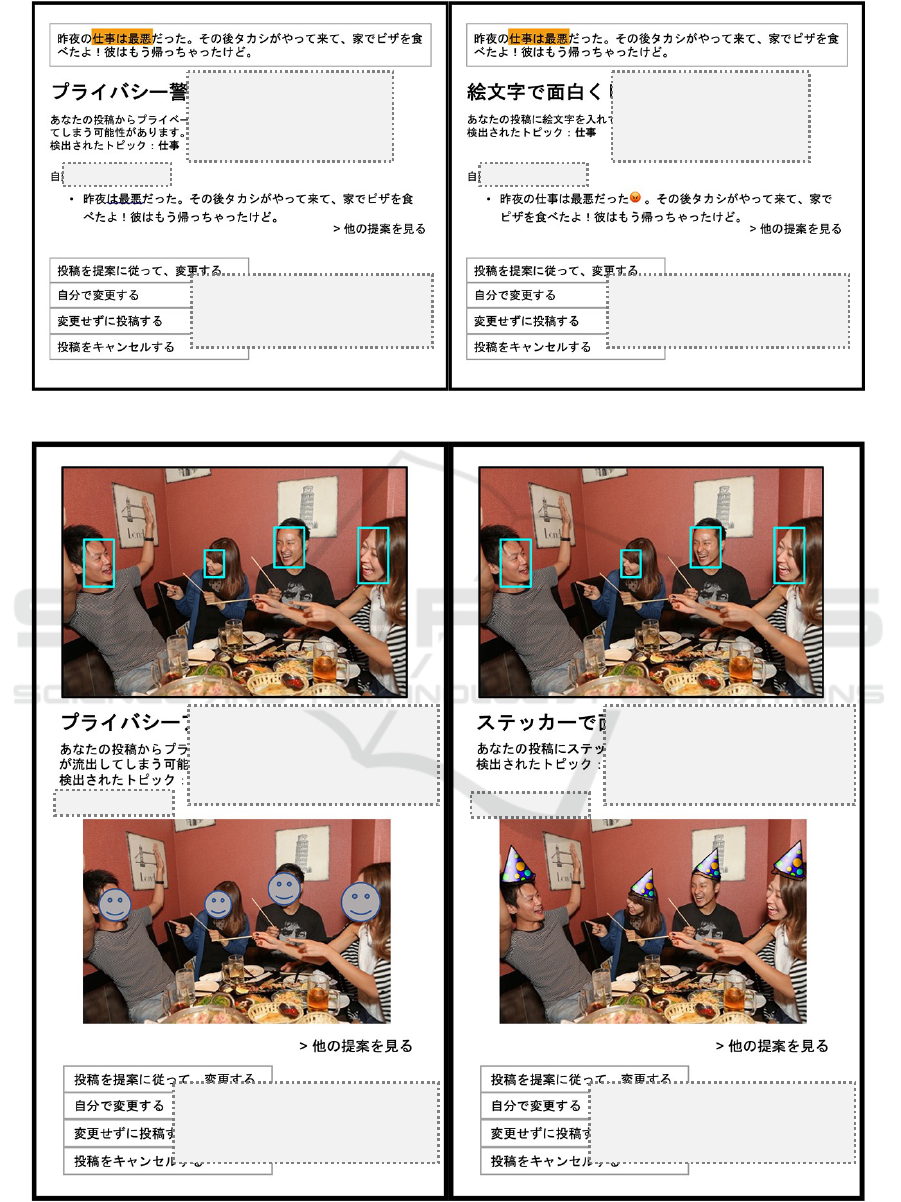

tion. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the detail of the tool

interfaces.

The overall design of the interfaces was similar for

all groups, with the only differences being related to

the type of tool (purpose) and the data (content) it ana-

lyzed. The hypothetical tools were also described in a

similar way, except when referring to the purpose and

content. To obtain opinions about the tools, we asked

the participants to “Please explain your reasons for

agreeing/disagreeing to the previous questions about

the app”, where “previous questions” referred to Lik-

ert scale questions such as “I would use this app in my

daily life”, “I can think of people I know who would

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

152

Make it fun with emojis!

Your post can be enhanced

with emojis

Topic detected: Work

Privacy alert!

Your post may reveal private

or sensitive information.

Topic detected: Work

Suggestion: Suggestion:

Change the post to the suggestion

Change the post manually

Post without change

Cancel posting

Change the post to the suggestion

Change the post manually

Post without change

Cancel posting

Figure 1: Interface for the experiment (translations added). Privacy (left) and Non-privacy (right) text tool.

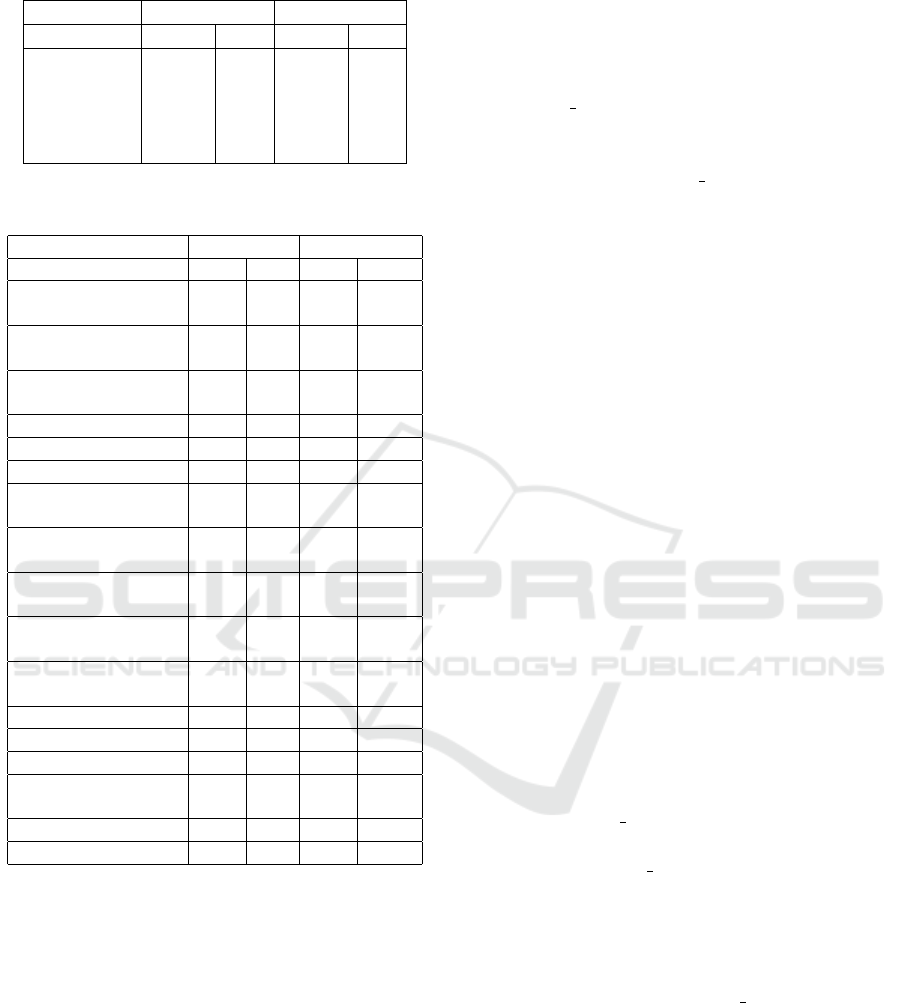

Make it fun with stickers!

Your post can be enhanced with

stickers

Topic detected: Party, drinks,

bystanders

Privacy alert!

Your post may reveal private or

sensitive information.

Topic detected: Party, drinks,

bystanders

Change the post to the suggestion

Change the post manually

Post without change

Cancel posting

Change the post to the suggestion

Change the post manually

Post without change

Cancel posting

Suggestion:

Suggestion:

Figure 2: Interface for the experiment (translations added). Privacy (left) and Non-privacy (right) image tool. Photos have a

CC0 license (public domain).

Perception of Privacy Tools for Social Media: A Qualitative Analysis Among Japanese

153

use this app”, “Using the app would get annoying”,

and “The app’s automatic suggestion is satisfying”,

adapted from (Hasan et al., 2019).

To gather the details of participants’ privacy con-

cerns towards the tools, we asked them to “Please

explain your reasons for agreeing/disagreeing to the

previous questions on privacy concerns about the

app”. The “previous questions” referred to questions

adapted from the Mobile Users’ Information Privacy

Concerns (MUIPC) scale (Xu et al., 2012), which

consists of the dimensions of Perceived surveillance

(adapted from (Smith et al., 1996): “I believe that the

location of my mobile device would be monitored at

least part of the time by the app”, “I am concerned

that the app could be collecting too much informa-

tion about me”, “I am concerned that the app could

monitor my activities on my mobile device”), Per-

ceived intrusion (adapted from (Xu et al., 2008): “I

feel that as a result of my using the app, others would

know about me more than I am comfortable with”,

“I believe that as a result of my using the app, in-

formation about me that I consider private would be

more readily available to others than I would want”, “I

feel that as a result of my using the app, information

about me would be out there that, if used, will invade

my privacy”) and Secondary use of personal informa-

tion (adapted from (Smith et al., 1996): “I am con-

cerned that the app could use my personal informa-

tion for other purposes without notifying me or get-

ting my authorization”, “When I give personal infor-

mation to use the app, I am concerned that it could use

my information for other purposes”, “I am concerned

that the app could share my personal information with

other entities without getting my authorization”). The

answers to the Likert scale questions are outside the

scope of this paper and are reported in (Bracamonte

et al., 2023).

3.2 Translation

All the text content, including the tool description and

interface, and the survey questions, was translated to

Japanese by a native speaker and independently re-

viewed by two Japanese native speakers. The trans-

lation was then revised with the feedback from the

two reviewers. Next, the translated content was back-

translated into English by other two Japanese native

speakers who were fluent in English. Finally, the orig-

inal and back-translated versions were checked by a

fluent English speaker, who validated that they were

comparable. In addition, the posts in the text-based

tools were adapted to refer to Japanese contexts where

necessary. With regards to the photos in the image-

based tools, these were adapted by choosing photos

that depicted Japanese people.

3.3 Participant Recruitment

An online survey company in Japan was used to re-

cruit participants and we specified a demographic

(age and gender) proportion similar to (Bracamonte

et al., 2022). At the beginning of the survey, we in-

formed participants about the purpose and character-

istics of the study and asked for their consent to par-

ticipate. Only participants who consented proceeded

to answer the survey.

The Ethical Review Committee at the Faculty of

Collaborative Regional Innovation (Ehime Univer-

sity, Japan) reviewed the study and approved it in

February 2023.

3.4 Qualitative Analysis

We used a hybrid qualitative analysis approach: we

combined a deductive approach that used a priori cat-

egories adapted from (Bracamonte et al., 2022) with

a general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006). New

categories were identified from the responses based

on the research objectives. An initial check of the data

was conducted by going through all responses. At this

stage we identified responses outside of the scope of

the analysis, where participants only answered “Don’t

know” or left the answer blank. After this step, the

principal coder developed and refined the codes for

the responses and categorized them. A second coder

then independently categorized the responses.

We evaluated the inter-rater reliability between the

two coders using Cohen’s kappa (Hallgren, 2012).

The analysis was conducted separately for each code,

due to some responses belonging to multiple cate-

gories. For the question on the opinion about the

tools, the mean of the kappas was 0.8 (minimum value

of 0.48). For the question on the reasons for privacy

concern towards the tools, the mean was 0.73 (min-

imum value of 0.48). In both cases, the inter-rater

reliability coefficients were within acceptable ranges.

4 RESULTS

We obtained a total of 540 responses, of which 35

were removed due to not being intelligible or show-

ing lack of comprehension, resulting in a valid sam-

ple of 505 respondents. The sample demographics are

detailed in Table 1. The age mean and gender distri-

bution was similar in all groups.

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

154

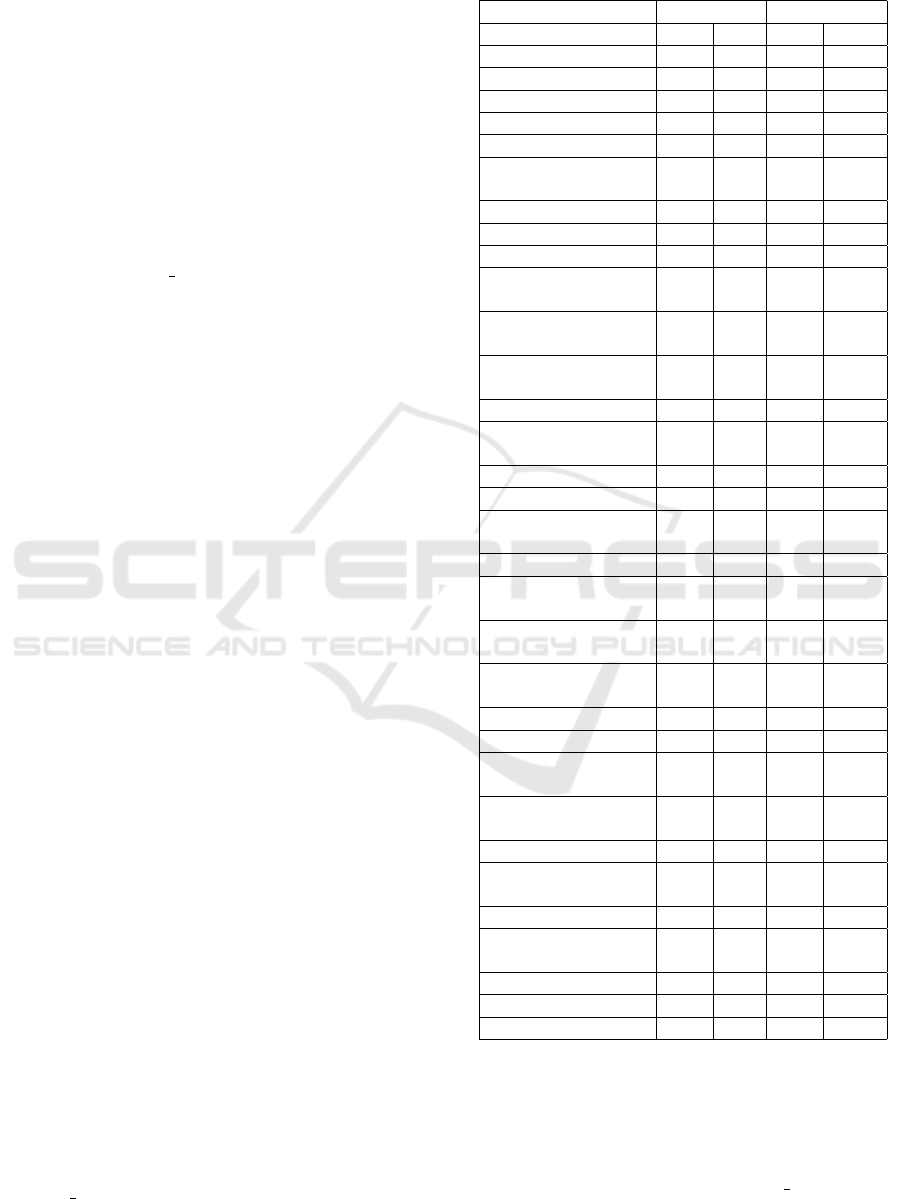

Table 1: Sample demographics.

Privacy NonPrivacy

Image Text Image Text

Total (n) 125 120 130 130

Age (mean) 36.3 37.4 37.29 36.9

Gender (n)

Female 46 48 46 48

Male 79 72 84 82

Table 2: Categories of answers about opinion about the

tools.

Category Privacy NonPrivacy

Img Txt Img Txt

Valuable for pri-

vacy protection

11 2 1 0

Privacy dimen-

sions

5 5 3 0

Feeling of being

assured

11 11 2 0

Self-efficacy 1 4 3 2

Unnecessary 7 19 14 22

Self-expression 0 6 6 16

Doubt effective-

ness

5 16 16 21

Not sure how to

use it

4 1 1 0

Bothersome and

time consuming

9 22 7 13

No opportunity to

use

13 5 5 5

Need to use to de-

cide

2 0 4 0

Convenient 13 6 14 21

Useful for others 5 1 1 1

Interesting 1 0 9 1

Not suitable for

themselves

0 0 1 4

Other app is better 0 0 2 0

Other 14 10 16 14

4.1 Reasons for Opinions About the

Privacy Tools

We report the results focusing on discussions of pri-

vacy, but also include the report of other relevant cate-

gories. The full list of identified categories are shown

in Table 2.

4.1.1 Privacy Concern-Related Reasons

Valuable for Privacy Protection. There were re-

spondents who recognized the value of the privacy

tool for its stated purpose. These were most often

found for the privacy tool for images, such as in the

following example:

“Our privacy is often violated nowadays.

Therefore, I would recommend others to use

the application like this. It is not so difficult to

use that anyone feels no stress when using it.”

(Privacy Image)

“...I think it is better to conceal their faces us-

ing the app so that their privacy can be prop-

erly protected.” (Privacy Image)

These respondents understood the scenario of a

potential privacy risk situation and how the privacy

tool could be used to manage those risks. For the

image privacy tool, the responses also showed un-

derstanding that sharing photos of others’ faces could

be a problem and recognized that the tool could help

avoid the privacy risk. Some respondents specifi-

cally mentioned the value of an automatic system that

would replace the manual tasks that are necessary for

privacy and personal data protection.

For the privacy tool for text, there were very few

responses of this category. Interestingly, we also iden-

tified one respondent who mentioned how the non-

privacy image tool could be adapted for use to protect

privacy.

Privacy Dimensions. There were also mentions of

concerns related to specific privacy dimensions such

as surveillance and perceived intrusion in their opin-

ion about the privacy tools. For example, there were

respondents who were concerned about privacy inva-

sion and data collection, due to the use of facial recog-

nition:

“... I think we should carefully consider the

use of this app, because it entails the risk of an

invasion of privacy caused by facial recogni-

tion.” (Privacy Image)

“Our facial information can be collected by

the app.” (Privacy Image)

These concerns were not limited to the privacy

tools. There were also instances in which respondents

worried about data collection in the non-privacy tool.

“...I would rather worry about providing photo

data to the app.” (NonPrivacy Image)

Feeling of Being Assured. Respondents mentioned

that the privacy tool gave them some assurance, and

that the alerts would be useful to avoid privacy-related

risks. Respondents recognized the convenience of be-

ing able to properly find and hide the faces of others

that have been unintentionally included in the picture.

These responses show that there is awareness of the

risks involved in revealing other people’s faces:

Perception of Privacy Tools for Social Media: A Qualitative Analysis Among Japanese

155

“I think it’s wrong to post others’ faces on-

line without their permission, putting aside

my own face. So, I think it is nice that the

app hides others’ face in the picture automati-

cally.” (Privacy Image)

There were also respondents who recognized that

there are risks even in the absence of malicious neg-

ligence and recognized the convenience of preventing

them:

“This application is useful to prevent an unin-

tended trouble caused by an indiscreet mes-

sage posted on SNSs, which enable us to

easily publish messages online... ” (Pri-

vacy Text)

4.1.2 Other Reasons

Among categories that were not specifically about pri-

vacy concerns, we identified reasons with a relation

to privacy protection or to the acceptance of privacy

tools.

Self-Efficacy. Some respondents reported the belief

in their own skill, where they are confident in their

full ability to make proper judgements about posting

content. In the case of the privacy tools, this was nat-

urally related to the purpose of privacy protection:

“When I post a photo online, I’m always care-

ful about the protection of my and others’ pri-

vacy. Therefore, I can make proper decisions

regarding privacy protection without AI sup-

port.” (Privacy Image)

“All we have to do is being careful about the

protection of our own privacy. Using this app

is just time consuming.” (Privacy Text)

Unnecessary. Respondents also felt that the privacy

tool was not necessary, either because they felt that

had no need of it or because they did not understand

the importance of privacy protection.

Doubt Effectiveness. Respondents also indicated

that they did not think that the privacy tool would be

effective for its purpose:

“It is difficult to decide whether the app’s sug-

gestions are appropriate or not. If everyone

revises as suggested by the app, the diversity

in expressions would be deteriorated. It is nice

for me that ideas I’m not aware of are offered.

If I use this app, I will create sentences prop-

erly by reference to the app’s suggestions.”

(Privacy Text)

“The app’s suggestions are not always under-

standable and acceptable. Such suggestions

should be given with the rationales for them.

Or, any user can understand how they protect

their privacy.” (Privacy Text)

Respondents had questions about the scope of facial

recognition, for example, and about understanding

why the privacy tool gave such an alert.

Respondents also appeared to exhibit doubt to-

wards the AI used in the hypothetical tools, regardless

of purpose:

“I would not like to depend on AI too much.”

(NonPrivacy Image)

“This app can be regarded as a tool for pre-

censorship using AI. This violates our free-

dom of expression.” (Privacy Text)

This last response is notable due to the term freedom

of expression, which is not frequently used among

Japanese respondents.

Self-Expression. For the text privacy tool, we iden-

tified responses that emphasized the importance of

self-expression. Respondents worried about the origi-

nality of the content and wanted to be able to commu-

nicate in their own words. Importantly, respondents

mentioned that they were worried about risks due to

de-contextualization of their posts or that it would be

different from what they had intended.

Bothersome and Time Consuming. Another cat-

egory frequently found among responses was the

worry or expectation that the privacy tool would be

annoying or complicated to use:

“I usually pay attention to others’ suggestions

when posting something online. This app

forces me to duplicate my efforts and is thus

bothersome.” (Privacy Text)

“If the app can detect privacy problems when

I post something online with no need for acti-

vating it, it is acceptable. Or, I don’t want to

use it.” (Privacy Image)

For this type of respondents, it may be just a matter of

operational time and effort. Conversely, if the privacy

tool was easy to use they might be feel it is accept-

able to use it. However, this type of opinion does not

imply that there is understanding of the importance of

privacy protection. These responses also offer an ex-

planation of why the privacy tool is considered both-

ersome, because there is a sense that it is too much

trouble to go back and redo the work.

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

156

No Opportunity to Use. Some respondents con-

sidered that there would have no opportunity to use

the privacy tool anyway, since they do not put other

personal information social networking sites without

proper permission. This may be typical of respon-

dents who are not active on social media or consider

themselves to be conscientious.

Convenient. On the positive side, there were re-

spondents that found the privacy tool convenient, be-

cause they consider that the tool eliminates having to

do the task on their own:

“It would reduce the effort to hide faces with

stamps” (Privacy Image)

Respondents also valued the options being presented

to help them make a decision. That is, they valued the

ability to resolve the confusion and difficulty of mak-

ing decisions about word choices, for example. What

was not clear is whether these respondents understand

the importance of privacy protection or whether they

were only judging the convenience.

Other. Finally, there were also respondents who

had different other reasons for their opinion of the

privacy tool, such as that it would be acceptable to

use if it was popular. Popularity or reputation can

be a source of assurance, and this perception may be

strong in Japan (Murata et al., 2014).

4.2 Reasons for Privacy Concern

Towards the Privacy Tools

We report the results focusing on categories related

to privacy and trust, and on categories which may in-

fluence acceptance of privacy tools. The full list of

identified categories are shown in Table 3.

4.2.1 Reasons Related to Privacy Concern

Dimensions

We found reasons related to all three of the dimen-

sions of privacy concern.

Data Collection. Respondents showed concerns

about their data being collected, and this category of

responses was one of the most frequent among all cat-

egories. We found that there was even acknowledg-

ment the risk of giving data even to protect privacy:

“I understand this app is designed to protect

users’ privacy. However, I’m concerned about

the app’s protecting our privacy in exchange

for our providing personal data to it.” (Pri-

vacy Text)

Table 3: Categories of answers about privacy concerns to-

wards the tools.

Category Privacy NonPrivacy

Img Txt Img Txt

Data collection 11 22 14 16

Tracking 5 12 2 8

Know about me 4 5 9 7

Sell/Share data 2 3 1 3

Data misuse 3 3 1 1

Institutional

(dis)trust

10 5 5 8

Tool (dis)trust 20 13 16 7

No concern 6 8 6 11

No interest 0 1 0 2

Gave up on pri-

vacy

5 1 6 6

Perception of

profit motivation

1 0 0 0

Worry (vague in-

secure feeling)

2 2 5 4

Security risk 8 10 9 9

Limited informa-

tion

4 0 0 1

Nothing to hide 0 1 0 0

Self-efficacy 0 3 3 2

Avoidance of un-

necessary apps

0 3 4 3

Tool permissions 2 2 0 0

Unknown reputa-

tion

0 0 2 0

Bothersome and

time consuming

1 2 0 0

Unclear effective-

ness

6 9 6 7

Unnecessary 0 2 4 3

Convenient 2 1 2 1

General privacy

concern

15 13 19 13

Other privacy con-

cern

4 4 4 3

Data processing 3 4 1 1

No information

about the tool

0 0 0 0

Assurance 4 4 0 0

Avoid posting in-

formation

2 1 3 0

Self-expression 0 0 2 2

New app distrust 0 0 2 1

Other 11 8 14 16

However, data collection concerns in general were

found for all types of tools:

“I’m afraid that my use of this app on a daily

basis would promote the collection of my per-

sonal data including those about my work and

human relationships.” (NonPrivacy Text)

Perception of Privacy Tools for Social Media: A Qualitative Analysis Among Japanese

157

Tracking. The respondents showed vague concerns

and uncomfortable feelings about being tracked, and

indicated a general dislike of the feeling of being “ob-

served”. We noted that for the text privacy tool, it ap-

peared to be related to people’s emotion and feeling,

whereas for image it appeared to be more superficial.

We hypothesize that the sense of surveillance is per-

haps stronger for text data.

“This application makes me feel that my ev-

eryday life is watched remotely more than I

currently suppose.” (Privacy Text)

“I feel that I’m not free at all owing to the app

and it’s indescribably creepy. Also, I feel it

monitors me. I don’t like these feelings. I

don’t need an application of this kind.” (Pri-

vacy Text)

Sell/Share Data. There was concerned expressed

about secondary use for commercial purposes and for

AI learning:

“I wonder if the app can learn personal stuff

from many photos and automatically send the

resultant data to somewhere else (e.g. to an

overseas server) for upgrading the app’s per-

formance through integrating it with data from

other sources.” (Privacy Image)

However, for most respondents, it appeared to be dif-

ficult to express this concern in detail and responses

with this level of knowledge about online systems

were few. In addition, respondents seemed to recog-

nize that there is a risk that personal data may be used

without malicious intent:

“Even if the app is operated without any mali-

cious intent, I can be a potential target of data

misuse through collecting my personal data

down to the last detail...” (Privacy Text)

Data Misuse. Only a few respondents exhibited un-

derstanding of how the app business model worked

and were worried about the misuse of their data, for

both the privacy and non-privacy tools. The following

response is remarkable also for being one of the few

direct reference to the privacy policy, which was not

often mentioned:

“For example, the misuse would lead to an in-

crease in the number of ads I receive, despite

the privacy policies that plausibly describe, for

example, they don’t identify an individual per-

son.” (NonPrivacy Image)

Know About Me. Finally, we identified intrusion-

related concerns such as obtaining knowledge about

the user. A few respondents mentioned in particular

private companies:

“I cannot support this system, because it is

outrageous that human rights violations are

committed by nothing but a private company.”

(Privacy Text)

4.2.2 Trust-Related Reasons

Institutional (Dis)trust. We identified responses

which indicated both trust and distrust towards apps

and providers in general:

“No one trusts on SNSs.” (Privacy Image)

“I think, in the current day, application devel-

opers properly develop and operate their apps.

Additionally, if users carefully download and

use apps, no harm would be caused.” (Pri-

vacy Text)

In both privacy and non-privacy groups, there were re-

spondents who mentioned their general low trust to-

wards apps. Some respondents did not provide de-

tailed information about their concern and may not be

considering specific effects of privacy risks. Rather,

they may seek to avoid any problem by avoiding use

of apps. Sometimes the respondents also indicated

general trust towards app developers, but these also

did not have a specific reason.

Tool (Dis)trust. Many respondents also reported

distrusting the tool itself, both in the privacy and non-

privacy groups. Most answers did not include detailed

reasons, but there were a few responses that appeared

to indicate specific anxiety regarding privacy, which

is perhaps unusual among Japanese (Murata et al.,

2014):

“Given that privacy policies, which declare

they never violate anyone’s privacy, are not

necessarily complied with now, I cannot agree

with the use of this app.” (Privacy Image)

The responses also revealed how general (dis)trust af-

fects certain apps, in this case new and perhaps not

widely disseminated apps:

“Unless 100% safety and security in pri-

vacy are guaranteed, I can’t help but worry

about my privacy. I feel new applications are

more suspicious than existing apps.” (NonPri-

vacy Image)

4.2.3 Privacy Mindset

No Concern. In some cases, respondents reported

they did not have any concerns about privacy regard-

less of the type of tool:

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

158

“I don’t think my private life is being exposed

by just using the app.” (NonPrivacy Image)

“I don’t perceive any risk such as personal

data leakage caused by an app that only cor-

rects sentences.” (NonPrivacy Text)

It may be that these respondents do not consider a

privacy risk anything other than a leak, and that data

analysis by apps in general does not lead to a privacy

violation. In these cases, they do not appear to con-

sider that the data may be shared outside of the apps

and it may be that the respondents do not understand

data processes in apps in general.

No Interest. We also identified a few Japanese re-

spondents that reported no interest in privacy issues,

rather no concern:

“Sensitivity to privacy depends on the person,

but I am not aware of it so much. Personal data

protection is not a serious issue. My home ad-

dress data should be protected, though.” (Pri-

vacy Text)

“I don’t worry about my privacy. It’s no prob-

lem for me that my personal data is collected

unless it contains credit card data or the like.”

(NonPrivacy Text)

Here the respondents do not consider an invasion

of privacy anything except the case of leakage of

personal information about financial assets, such as

credit card information. This type of responses indi-

cates a lack of interest in privacy protection and a lack

of perceived risk.

Gave up on Privacy. Some respondents seemed to

think that privacy risks are so common that they have

given up worrying about the risks themselves.

“Using any website entails a risk at least to an

extent. So, we don’t need to worry about it

more than necessary.” (NonPrivacy Image)

“We have no privacy nowadays.” (Pri-

vacy Image)

The responses also included some extreme views that

there is no privacy once the personal information has

been disseminated. The respondents mentioned that,

therefore, they had given up on privacy protection in

the current situation due to mistrust, and consequently

also given up on checking whether privacy protection

was being provided. However, we note that this type

of responses did not appear to reflect a serious feeling,

but rather resignation and a realistic point of view.

Security Risk. Respondents seemed to understand

that it is difficult for individuals to recognize how

the tools work (both privacy and non-privacy) and are

aware that there is a security risk of information being

leaked.

“I’m very worried that this app would collect

and store my data while using it. The risk

of the leaks of my data bothers me.” (Pri-

vacy Image)

“The news of data leaks, which is occasion-

ally reported, discomforts me. Moreover, I’m

concerned about invisible or unreported harms

caused by the leaks.” (Privacy Text)

“Undetected data leaks associated with online

application usage have often occurred. So,

there is no reason that I can believe this ap-

plication is no problem.” (NonPrivacy Image)

There were also responses that seemed to show anx-

iety that the damage caused by information leaks

would not be properly reported and analyzed. Japan

has experienced cases of data leakage, some which

involved children’s data (Nikkei Asia, 2014) which

were widely reported and concerned the general pub-

lic. This type of incidents might be behind the re-

spondents’ worry about things that cannot be “seen”.

This is an understandable concern, since it is difficult

for users to understand the extent of security risks and

how the privacy tool works.

General Privacy Concern. This category was one

of the most frequently found in the responses. How-

ever, it mostly consisted of very general statements

about worry for privacy overall, without further de-

tail.

4.2.4 Perceived Control

Data Processing. Respondents felt that not enough

information was provided about how the privacy tool

worked and that increased their concern. This was

also the case for some respondents in the non-privacy

groups. These respondents recognized that the tool’s

mechanism or business model was not clear to them:

“I am not sure how the app works, and there-

fore I don’t know how much personal data will

be provided.” (Privacy Image)

“I don’t know what algorithm is working, so

I can’t judge whether the app is acceptable or

not.” (NonPrivacy Text)

Tool Permissions. Some respondents also reported

concern about the settings provided by the privacy

Perception of Privacy Tools for Social Media: A Qualitative Analysis Among Japanese

159

tools, and how much control they would have over

it:

“I think the application will not cause a seri-

ous problem, unless application management

settings or the like are automatically con-

trolled.” (Privacy Image)

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Opinion About the Privacy Tool

On the whole, many respondents did not feel the need

to use a privacy tool. However, there were also re-

sponses that made mention of how the privacy tool

was valuable for privacy and could provide assurance

that privacy risks could be avoided. The results show

that there were respondents who mentioned privacy

concerns (related to surveillance and intrusion) in the

answers about their general opinion of the privacy

tool, which indicates that there is awareness of pri-

vacy issues among the Japanese respondents’. While

this may not be an overall tendency among all respon-

dents, but rather the opinion of a limited group, it

does provide a view that this kind of privacy aware-

ness is present in the Japanese users and that the pri-

vacy tool can have a priming effect that brings it forth.

It was also notable that a number of respondents re-

ported concerns related to privacy dimensions in the

non-privacy tool groups, without being asked directly

about it.

The results also show that there are participants

who have thought about the risks of social media and

the convenience of a privacy tool for protecting their

privacy on these platforms. The privacy tool for im-

ages tended to be positively evaluated as a mechanism

to enhance privacy protection of images uploaded on-

line. However, in general many respondents felt that

the tools could become annoying or that it would

take too much effort to use them. Ease of use and

usefulness are important factors for the acceptance

of privacy-enhancing technology (Abu-Salma et al.,

2017), and therefore the perception that the tools are

troublesome might stop people from using them.

We found that a few respondents also reported

wanting to feel in control of their privacy and felt a

lack of freedom of expression due to the tool. The de-

sign of automated tools for social media privacy may

be challenged by trying to find a balance between ease

of use and control. This balance could be achieved by

providing flexible options for those users that require

them, but also providing easy-to-use default settings

or by automatically running the tool. Similar opin-

ions were also expressed for the non-privacy tool, so

in addition, this may be evidence of a lack of trust in

AI or automated processes to some extent. Although

not from a privacy perspective, it shows an aversion to

being controlled by technologies. This type of users

may not want their own posts to be modified by AI

technology, even for privacy reasons.

We also observed that the privacy tool for text

tended to be more negatively evaluated as unneces-

sary or ineffective, in contrast with the privacy tool

for images. This brings the question of whether the re-

spondents considered that posting images online was

more likely to result in risk of violating one’s own pri-

vacy or the privacy of others compared to text post-

ing. Nevertheless, it is difficult to say whether the

respondents who positively evaluated the privacy tool

for image have a clear definition of privacy and its im-

portance. Data protection may not be not itself an end

for them.

5.2 Privacy Concern Reasons

Respondents showed concern about malicious mech-

anisms built in the tools and of insidious intent of

the tool provider or operator. They were particularly

worried that their personal data would be collected

and stored covertly by the tool and shared among

other parties, regardless of under which condition

the tool was used. Respondents also had somewhat

vague concerns about the reliability of the tools. They

pointed out the risks of unauthorized personal data

sharing, tracking, data leaks and data security risks.

The results show that respondents were aware of

the importance of privacy protection, but this aware-

ness appeared to lead to a vague concern about pri-

vacy and security issues when using the tools. One of

the few exceptions was that respondents specifically

mentioned face recognition, although the description

in the study mentioned other types of information that

could be detected by the hypothetical tool. The design

of the interface might have led respondents to assume

that the tool only detected people’s faces in images to

protect their privacy. But images can contain other in-

formation related to privacy issues like locations and

events. Examples of these were included in the inter-

face as detected information, but were not mentioned

by the respondents. For text-based tools, there were

also many respondents who worried about privacy is-

sues such as data collection, and those who acknowl-

edged the importance of privacy protection and high-

lighted the potential risks caused by the usage of on-

line apps.

That this type of detailed responses was present

indicates that there are Japanese users who possess

a level of privacy knowledge, although they may not

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

160

be the majority. General anxiety or worry was more

common overall, which may be due to a lack of

knowledge about issues such as the existence of data

brokers in Japan, as opposed to the USA, for exam-

ple. In addition, Japanese participants may lack un-

derstanding of the way that online platforms work.

Rather, respondents showed a general uncertainty that

personal data would “probably” be used, but may not

understand in detail how.

In general, the respondents’ answers indicated that

in many cases privacy concerns and distrust were di-

rected to all kinds of apps, rather than specifically to

the tools in the survey. Respondents considered that

information security and data protection could not be

completely ensured as long as they used online ap-

plications, including social media sites. Respondents

seemed to be ambivalent about using online services

in terms of privacy risks. On the one hand, respon-

dents may not trust in the benevolence of companies

which provide general online services or in the quality

of their online applications. On the other hand, how-

ever, they may feel that they cannot avoid the use of

online services for convenience in their everyday life.

For example, when using hospital services it would

difficult for a user to avoid providing personal infor-

mation, but in those cases there is an expectation that

providing information will not cause harm and that

the data will not be shared.

Research has found that in practice, privacy pre-

serving behavior depends on the context. (Fukuta

et al., 2022) conducted an experimental survey to in-

vestigate the type of information that app users check

when selecting and downloading apps, which showed

that participants paid little attention to the disclosure

of personal information to the app developer when

selecting an app. Japanese students in the study ap-

peared to choose apps with little or no concern about

details such as what personal information they were

providing, for what purpose and whom was the de-

veloper to which the information was being provided.

These Japanese students downloaded many apps but

at the same time believed that privacy is important.

There is a possibility that this type of users might

show acceptance of a privacy tool, that even if the

tool is considered bothersome they might think it is

acceptable if it helps them with privacy awareness.

5.3 Limitations

We were specifically interested in the opinions of

Japanese social media users, who frequently make use

such platforms, who have reported being concerned

about their privacy online, and who could therefore

potentially benefit from the use of privacy tools. How-

ever, the findings among this sample may not be eas-

ily generalizable to other populations. In addition, for

the qualitative analysis we based the categorization on

privacy research conducted among a USA sample and

created new categories as a result of the information

uncovered in the Japanese responses. We found sim-

ilarities and differences with previous research, and

we do not reject the possibility that a different cod-

ing approach could reveal additional perspectives. Fi-

nally, we presented participants with a non-interactive

prototype of the tools and a brief description, and ob-

tained their opinions based on that information. The

use of a privacy tool was outside the scope of this

study, but real interaction may affect how Japanese

users perceive the benefits, disadvantages, or risks of

these tools. Future research should consider evalu-

ating privacy concerns with interactive prototypes or

actual use.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we conducted a qualitative analysis of

responses of Japanese social media users to open-

ended questions on their opinion and privacy con-

cerns towards a privacy tool and compared them to re-

sponses towards a non-privacy tool. The results sug-

gest that respondents’ opinions were influenced by

general privacy concerns along with an overall dis-

trust of apps and providers. Although there were

some surveillance and intrusion worries due to the

nature of the privacy tool, these were not frequent,

and few respondents gave detailed reasons for their

concern. When compared to the opinions about a

non-privacy tool, we found similar results that suggest

general privacy anxiety, rather than specific concerns.

The findings suggest that among Japanese users, a pri-

vacy tool for social media content would face chal-

lenges that are the result of an attitude of general con-

cern about the privacy risks of online apps.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The second, third and fourth authors were supported

by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 20K02000,

22K02063, 23K01545.

REFERENCES

Abu-Salma, R., Sasse, M. A., Bonneau, J., Danilova, A.,

Naiakshina, A., and Smith, M. (2017). Obstacles to

the adoption of secure communication tools. In 2017

Perception of Privacy Tools for Social Media: A Qualitative Analysis Among Japanese

161

IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pages

137–153.

Adams, A. A., Murata, K., Orito, Y., and Parslow, P. (2011).

Emerging social norms in the UK and Japan on pri-

vacy and revelation in SNS. The International Review

of Information Ethics, 16:18–26.

Bracamonte, V., Orito, Y., Murata, K., Fukuta, Y., and Iso-

hara, T. (2023). Privacy Concerns Towards Privacy

Tools for Social Media Content: A Comparison be-

tween Japan and the USA. Computer Security Sympo-

sium 2023 CSS2023, pages 1435–1442.

Bracamonte, V., Pape, S., and Loebner, S. (2022). “All apps

do this”: Comparing privacy concerns towards privacy

tools and non-privacy tools for social media content.

Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol., 2022(3).

Bracamonte, V., Tesfay, W. B., and Kiyomoto, S. (2021).

Towards exploring user perception of a privacy sensi-

tive information detection tool. In ICISSP, pages 628–

634.

Caliskan Islam, A., Walsh, J., and Greenstadt, R. (2014).

Privacy detective: Detecting private information and

collective privacy behavior in a large social network.

In Proceedings of the 13th Workshop on Privacy in

the Electronic Society, WPES ’14, pages 35–46, New

York, NY, USA. ACM.

Fukuta, Y., Murata, K., and Orito, Y. (2022). Personal In-

formation Disclosure as a Secondary Action of Con-

sumer Purchase Behaviour. In Proceedings of 83th

Annual Conference of the Japan Society for Informa-

tion and Management, pages 95–98.

Guarino, A., Malandrino, D., and Zaccagnino, R. (2022).

An automatic mechanism to provide privacy aware-

ness and control over unwittingly dissemination of

online private information. Computer Networks,

202:108614.

Hallgren, K. A. (2012). Computing Inter-Rater Reliabil-

ity for Observational Data: An Overview and Tuto-

rial. Tutorials in quantitative methods for psychology,

8(1):23–34.

Hasan, R., Li, Y., Hassan, E., Caine, K., Crandall, D. J.,

Hoyle, R., and Kapadia, A. (2019). Can Privacy

Be Satisfying?: On Improving Viewer Satisfaction

for Privacy-Enhanced Photos Using Aesthetic Trans-

forms. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, page 367.

ACM.

Li, F., Sun, Z., Li, A., Niu, B., Li, H., and Cao, G. (2019).

HideMe: Privacy-Preserving Photo Sharing on Social

Networks. In IEEE INFOCOM 2019 - IEEE Confer-

ence on Computer Communications, pages 154–162.

Lowry, P. B., Cao, J., and Everard, A. (2011). Privacy

concerns versus desire for interpersonal awareness in

driving the use of self-disclosure technologies: The

case of instant messaging in two cultures. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 27(4):163–200.

Mao, H., Shuai, X., and Kapadia, A. (2011). Loose tweets:

an analysis of privacy leaks on twitter. In Proceedings

of the 10th annual ACM workshop on Privacy in the

electronic society, pages 1–12.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

(Japan) (2023). Precautions for the use of SNS.

https://www.soumu.go.jp/main\ sosiki/cybersecurity/

kokumin/enduser/enduser\ security02\ 05.html.

Murata, K. and Orito, Y. (2013). Internet Users’ Online

Privacy Protection Awareness: Ideal and Reality. In

Proceedings of 67th Annual Conference of the Japan

Society for Information and Management, pages 65–

68.

Murata, K., Orito, Y., and Fukuta, Y. (2014). Social

attitudes of young people in Japan towards online

privacy. Journal of Law, Information and Science,

23(1):[137]–157.

Nikkei Asia (2014). Customer data leak deals blow to

Benesse. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Customer-

data-leak-deals-blow-to-Benesse.

Orito, Y. and Murata, K. (2014). How do users recognise

business models and privacy protection of social me-

dia companies? In Proceedings of 68th Annual Con-

ference of the Japan Society for Information and Man-

agement, pages 157–160.

Orito, Y., Murata, K., and Fukuta, Y. (2013). Do online

privacy policies and seals affect corporate trustwor-

thiness and reputation? The International Review of

Information Ethics, 19(0):52–65.

Sleeper, M., Cranshaw, J., Kelley, P. G., Ur, B., Acquisti, A.,

Cranor, L. F., and Sadeh, N. (2013). “I read my Twit-

ter the next morning and was astonished” A Conversa-

tional Perspective on Twitter Regrets. In Proceedings

of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Com-

puting Systems, CHI ’13, pages 3277–3286.

Smith, H. J., Milberg, S. J., and Burke, S. J. (1996).

Information Privacy: Measuring Individuals’ Con-

cerns about Organizational Practices. MIS Quarterly,

20(2):167–196.

Statista (2023). Number of social media users in japan

from 2019 to 2023 with a forecast until 2028.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/278994/number-

of-social-network-users-in-japan/.

Tesfay, W. B., Serna, J., and Rannenberg, K. (2019). Pri-

vacyBot: Detecting Privacy Sensitive Information in

Unstructured Texts. In 2019 Sixth International Con-

ference on Social Networks Analysis, Management

and Security (SNAMS), pages 53–60.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A General Inductive Approach

for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. American

Journal of Evaluation, 27(2):237–246.

Wang, Y., Norcie, G., Komanduri, S., Acquisti, A., Leon,

P. G., and Cranor, L. F. (2011). ”I regretted the minute

I pressed share”: A qualitative study of regrets on

Facebook. In Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium

on Usable Privacy and Security, SOUPS ’11.

Xu, H., Dinev, T., Smith, H., and Hart, P. (2008). Exam-

ining the Formation of Individual’s Privacy Concerns:

Toward an Integrative View. ICIS 2008 Proceedings.

Xu, H., Gupta, S., Rosson, M. B., and Carroll, J. M. (2012).

Measuring mobile users’ concerns for information pri-

vacy. In International Conference on Information Sys-

tems, ICIS 2012, International Conference on Infor-

mation Systems, ICIS 2012, pages 2278–2293.

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

162