A Cascade of Consequences: Improving an Accident Analysis Method by

Learning from a Real Life Telecommunications Accident

Hans C. A. Wienen

1

, Faiza A. Bukhsh

1

, Eelco Vriezekolk

2

and Luís Ferreira Pires

1

1

Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Twente, Netherlands

2

Dutch Authority for Digital Infrastructure, Netherlands

Keywords:

Telecommunications, Accident Analysis, Incident Analysis.

Abstract:

Telecommunications networks are vital enablers of modern society. Large accidents in these networks that

cause their unavailability can therefore have a severe impact on the functioning of society. Learning from

these accidents can help prevent them and thus make our society more resilient. In this paper, we present

an accident analysis method (TRAM) which we have developed by extending the AcciMap method and we

report on its application to analyse a severe accident in a telecommunications network. We validate notation

for representing and breaking positive feedback loops in a network breakdown, and we suggest a method to

enhance the prioritisation of recommendations derived from our analysis. Furthermore, our research reveals

that splitting the analysis based on the expertise of the method’s participants negatively impacts the efficiency

of the overall process.

1 INTRODUCTION

Telecommunications networks constitute one of the

critical infrastructures that make society work. Much

attention is therefore paid to the stability and re-

silience of these networks. When accidents

1

do oc-

cur, accident analysis yields insights that can help pre-

vent future accidents and improve the stability and re-

silience of telecommunications networks.

Our research aims to improve existing accident

analysis methods in the telecommunications sector. In

our previous case studies, we designed and validated

an accident analysis method called TRAM, which en-

ables the modelling and analysis of the distinctive fea-

tures associated with incidents in telecommunications

and cyberattacks (Wienen et al., 2019; Wienen et al.,

2024). Our investigation is carried out in real-world

corporate settings, characterized by time constraints

and limited collaboration opportunities in which these

companies operate. This precludes us from con-

ducting controlled experiments. Instead we apply

TAR (Technical Action Research) (Wieringa, 2014)

to identify new issues during the tests and validation

of our accident analysis method. We put our method

1

In the telecommunications domain, accidents are of-

ten referred to as ‘incidents’ . This paper will consistently

use the term ‘accident’ to align with the terminology in the

accident analysis field.

to the test in an uncontrolled environment, and as the

tests progress, the method is adapted to handle un-

expected issues encountered during those tests, hence

yielding an improved version of the method.

As outlined in our previous case study (Wienen

et al., 2024), we concluded that the current version

of TRAM lacks the ability to model positive feedback

loops, while these types of loops can play a crucial

role in telecommunications accidents. We also ob-

served that the number of recommendations for im-

provement TRAM yielded was large. Prioritising rec-

ommendations for implementation is not trivial, yet

TRAM originally did not give guidelines on how to

make these choices.

TRAM prescribes that subject matter experts

should discuss causes and consequences that lead to

the accident being analysed. We have seen in pre-

vious research (Wienen et al., 2019; Wienen et al.,

2024) that splitting the group according to different

phases in the accident can increase the efficiency of

the method, but we wanted to investigate if splitting

the group according to expertise yields a further in-

crease in efficiency. Together with a large telecom-

munications operator we performed a case study in

which we could analyse a large incident in a telecom-

munications network that led to the large scale un-

availability of telecommunications services in a West-

ern European country. In the analysis of this acci-

62

Wienen, H., Bukhsh, F., Vriezekolk, E. and Ferreira Pires, L.

A Cascade of Consequences: Improving an Accident Analysis Method by Learning from a Real Life Telecommunications Accident.

DOI: 10.5220/0012762800003756

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications (DATA 2024), pages 62-70

ISBN: 978-989-758-707-8; ISSN: 2184-285X

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

dent, we investigate these three questions (notation

for a feedback loop, prioritising recommendations

and splitting the group according to expertise).

This article makes the following contributions:

(i) it validates the new notation we introduced in

(Wienen et al., 2024); (ii) it suggests ways to priori-

tise the implementation of recommendations resulting

from TRAM; and (iii) it discusses the impact of split-

ting the analysis over two groups of experts according

to expertise.

The paper is further structured as follows: Sec-

tion 2 discusses accident analysis methods; Section 3

describes the TRAM method; Section 4 describes the

accident that we used to improve and validate TRAM.

Section 5 presents the results of the application of

TRAM to this accident and Section 6 discusses these

results. Section 7 concludes this paper.

2 ACCIDENT ANALYSIS

METHODS

Three different families of accident analysis methods

can be identified in the literature (Hollnagel, 2002;

Hollnagel and Goteman, 2004; Wienen et al., 2018):

Sequential Methods. Methods that represent an ac-

cident as the outcome of a sequence of events.

Epidemiological Methods. Methods that represent

an accident as the outcome of a sequence of events

that could take place in an environment in which

the measures that should have inhibited the se-

quence to result in an accident were malfunction-

ing or missing. They take the socio-technical

context into consideration, also discussing aspects

such as company culture, risk management, bud-

geting choices and safety regulations.

Systemic Methods. Methods that not only take the

socio-technical context into account, but try to

model the system in which the accident has devel-

oped, thus also looking at the tight links between

parts of the system, positive and negative feed-

back loops and discrepancies between the men-

tal model based on which operators take decisions

and the physical reality that they are influencing.

Some methods do not fall into one of the three afore-

mentioned families; these methods are mostly ad hoc

and the subject of very limited research (Wienen et al.,

2018).

The development of the three families is chrono-

logical. The sequential methods were developed

first. The Fault Tree Analysis method (Vesely et al.,

1981) is an example of such a method. Starting in

the 1990s, the relevance of the socio-technical con-

text became apparent, and the first epidemiological

methods were developed (Reason, 1990; Rasmussen,

1997). Finally, in the 2000s, system-theoretical as-

pects were introduced, resulting in the development

of systemic methods, such as STAMP (Leveson, 2004)

and FRAM (Hollnagel and Goteman, 2004). This evo-

lution was triggered by new accidents that could not

satisfactorily be analysed by the existing methods.

The relevance of the socio-technical context became

evident after, amongst others, the Bhopal disaster, the

Challenger explosion and the Chernobyl nuclear dis-

aster (Reason, 1990). The development of the sys-

temic methods started as software took a more promi-

nent role in both the design and the running of sys-

tems, thereby creating new vectors for disaster (Leve-

son, 2004).

In our research, we started with the most cited epi-

demiological method, namely AcciMap (Rasmussen,

1997; Branford et al., 2009), rather than a systemic

method. Systemic methods take more effort as they

typically include a data gathering and analysis phase

to model the context of the accident (Salmon et al.,

2012). This phase is too expensive, since it involves

an analysis of the organisation (including training

programs and company regulations), government pol-

icy and regulations, and regulatory bodies (Salmon

et al., 2012) which costs a considerable amount of ef-

fort. Systemic methods are therefore not appropriate

for most commercial companies.

When we performed our first case study with

AcciMap for an accident in telecommunications (a

DDOS-attack on a Western European telecommunica-

tions provider) (Wienen et al., 2019) we observed that

ICT aspects were given too little attention in the Ac-

ciMap methods described in literature. These aspects

form a critical part of any telecommunications opera-

tor and of the technology that also enables malicious

actions, such as cyberattacks. We introduced the ICT

layer to better analyse these aspects and we also de-

vised several ways to improve the efficiency of the

method. These changes gave rise to the Telecommu-

nications related AcciMap (TRAM) method.

3 TRAM

TRAM is an extension of the Generic AcciMap Method

by Branford (Branford et al., 2009), which is a way

to apply AcciMap and to make it practically useful.

In its essence, the Generic AcciMap Method maps a

graph of causes and consequences to a set of layers

that represent the organisation in which the accident

occurred, the external world, the physical world in

A Cascade of Consequences: Improving an Accident Analysis Method by Learning from a Real Life Telecommunications Accident

63

outdated

design

principles

ddos attack

misconfigured

firewall

unavailable

services

untrained staff

market

pressure

lower prices

insufficient

funds

External

Organisation

ICT

Physical / Actor

Outcomes

T

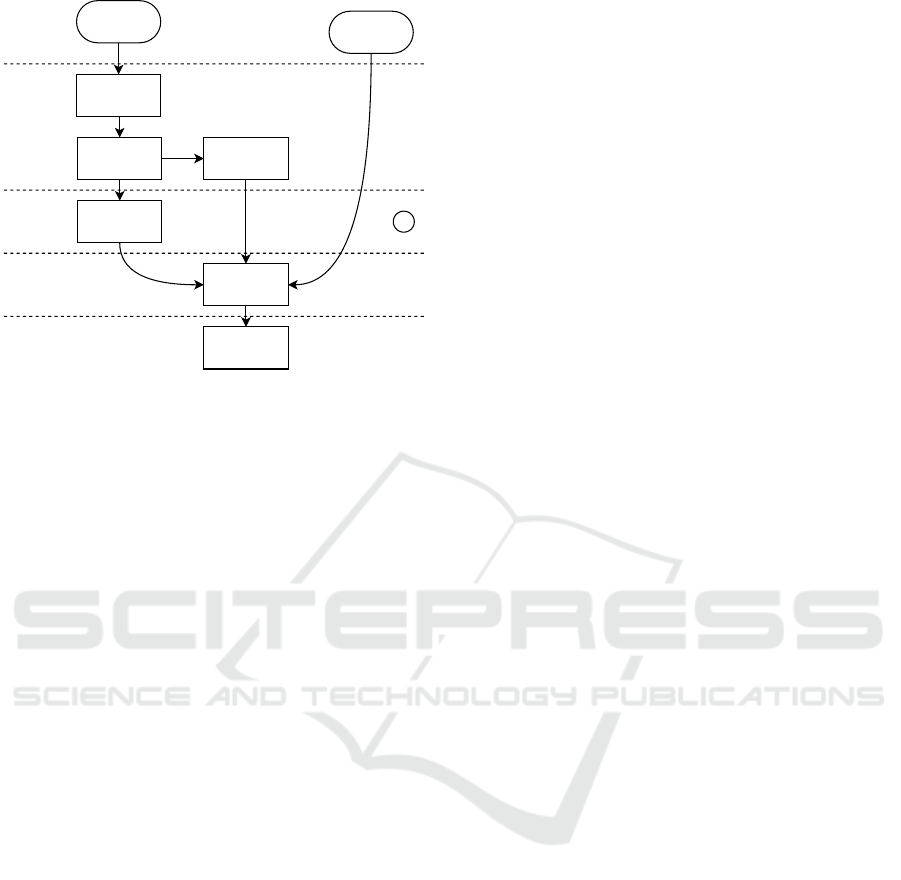

Figure 1: A constructed example of a TRAM diagram.

which actors perform actions and a layer that contains

the outcomes.

3.1 Method Overview

Figure 1 shows an example of a TRAM diagram. Our

additions to the Generic AcciMap Method are indi-

cated by T

l

in the figure and in the text that follows.

To apply TRAM, we organise workshops with sub-

ject matter experts from the organisation in which the

accident occurred. We then analyse the accident ac-

cording to the following steps:

1. Prepare the Analysis Workshop. Study avail-

able documentation to prepare the analysis

workshops and to draw up a list of participants.

2. T

l

Identify the Physical Path. Identify the tech-

nical failures that caused the accident and draw a

diagram representing these technical failures. In

this way, a common picture is formed among the

participants in neutral terms, helping avoid the

‘blame game’.

3. T

l

Split the Accident and the Group. The acci-

dent can sometimes be split into two distinct

phases, such as e.g. a short-lasting power outage

and a subsequent longer service outage, or the on-

set of the actual accident and the resolution of the

crisis situation caused by the accident. If this is the

case, split the group so that each phase of the acci-

dent is analysed by the staff involved in that phase.

4. Identify the Outcomes. Identify the conse-

quences of the accident. These may be detrimen-

tal, but also beneficial, such as using the crisis to

implement long-delayed improvements.

5. Identify the Causal Factors. Identify all causal

factors (these are the nodes in the causal chain of

events or the boxes in the diagram). In this step,

it is pertinent that the group does not limit itself to

actual events, but also takes into account measures

that were supposed to stop the development of the

accident or mitigate consequences, but failed.

6. T

l

Identify the Appropriate Layer. A TRAM di-

agram is layered, containing layers for External,

Organisational, ICT and Physical/Actor causal fac-

tors. Each causal factor is plotted in a layer.

7. T

l

Bring the Groups and the Diagrams To-

gether. If the group has been split in step 3, the

groups are now recombined, review each other’s

diagrams and combine the diagrams.

8. Fill Gaps and Check Logic. In this step, the

group walks through the whole causal chain, iden-

tifying missing causal factors and faulty links, fi-

nalising the diagram.

9. Formulate Recommendations. For each causal

factor, the group discusses how to prevent those

factors from happening, how to control them if they

are happening and how to compensate or mitigate

the consequences once the factor has happened.

These recommendations must be formulated in ac-

tionable form as they are the harvest of the analy-

sis.

When creating TRAM, we added steps and layers as

indicated above. We also defined additional nota-

tion to indicate positive feedback loops and heuris-

tics to discuss Crisis Management after the acci-

dent occurred. This resulted in a 25% more effi-

cient approach by splitting the group and avoiding

discussions about blame, as well as a more effective

approach by clearly indicating ICT aspects and by

adding Crisis Management to the analysis (Wienen

et al., 2024).

3.2 Positive Feedback Loops

TRAM diagrams are cause-and-effect diagrams, so

that in essence they are directional non-circular

graphs. In (Wienen et al., 2024) a positive feedback

loop was instrumental in causing the accident. Ade-

quately representing these loops in a strict cause-and-

effect diagram is hard, because it either requires a

repetitive string of actions, or the positive feedback

loop must be modelled as a single event. However,

in the latter case, the parts that make up the loop and

the way to break it are not represented. This is why

we introduced new notation to represent these loops.

We relaxed the non-circularity requirement, enabling

us to draw the feedback loop with adequate details to

show where the loop could be interrupted. The nota-

tion consists of a valve symbol (▷◁) to indicate where

DATA 2024 - 13th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

64

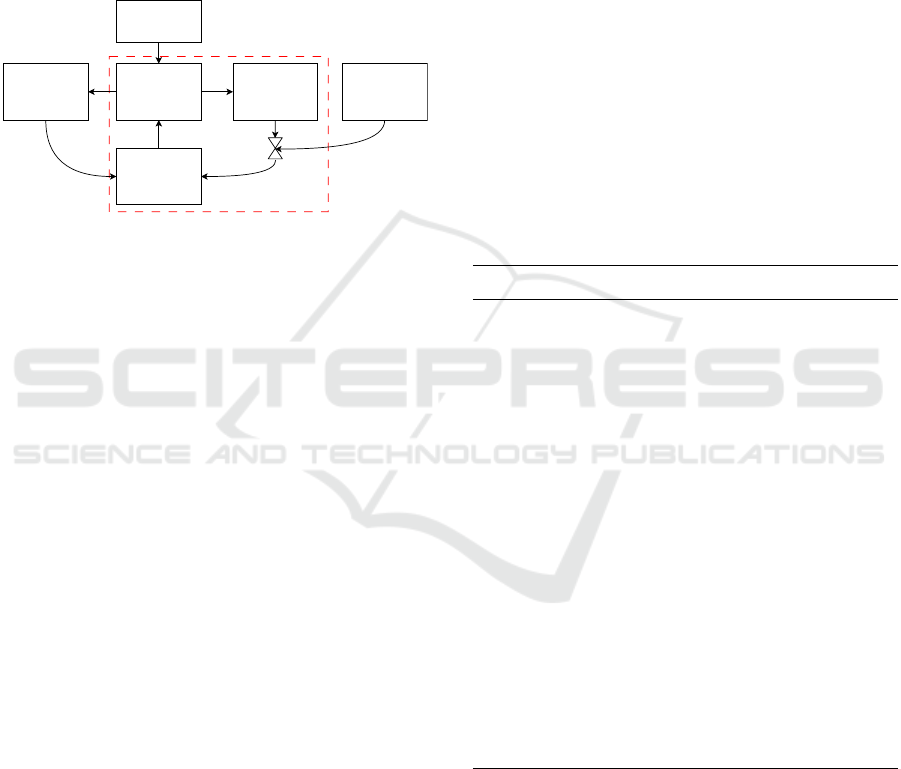

the loop was interrupted and which action interrupted

the loop. Figure 2 shows an example of this nota-

tion. This is the actual feedback loop that appeared in

our case study. The numbers in the boxes refer to the

numbers in Figure 3. The feedback loop is indicated

by the dashed red box; the action to break the feed-

back loop is indicated by the square with the arrow

pointing at the middle of the ▷◁ symbol, while the ▷◁

symbol itself indicates the link that is cut to break the

loop.

signalling storm

as signalling

volume

grows(#38)

4G subscribers

cannot attach to

network (#40)

phones keep

trying to

reconnect to 4G

service (#35)

block access to

network for all

phones

massive switch

to 2G and 3G

(#34)

complete stop of

HSS (#37)

Figure 2: Application of the notation we introduced

in (Wienen et al., 2024) to the feedback loop that was in-

strumental in the accident in this case study.

3.3 Prioritising Recommendations

Previous applications of the method (Wienen et al.,

2019; Wienen et al., 2024) yielded many recommen-

dations (136 recommendations in Case Study 1 and

63 recommendations in Case Study 2). Choosing

which recommendations to implement and in what or-

der is not trivial. For this reason, we wanted to inves-

tigate in the current case study if we could prioritise

the recommendations according to two methods: (i) a

cost-benefit analysis in which we use a scale from 1

to 5 on both axes and (ii) a maturity model.

Many maturity models are described in the litera-

ture (Smit, 2005; Mahal, 2008; Junttila, 2014; Reis

et al., 2017; Malone et al., 2020) and some mod-

els even describe how to build maturity models, such

as (Maier et al., 2012). (Junttila, 2014) identifies

six different maturity model development processes,

while(Malone et al., 2020) describes 21 different ma-

turity models for 6 different domains, such as Busi-

ness Intelligence, Human Resources and Software

Development / Technology. Maturity models typi-

cally have two dimensions (Lacerda and von Wangen-

heim, 2018): (i) one dimension that describes process

areas, capabilities or characteristics of the domain,

and (ii) one dimension that describes the maturity the

organisation has achieved in one of the process areas

or capabilities in the first dimension.

We chose to use discrete levels for the maturity

dimension instead of a continuous scale so that the

participants in the case study can more easily order

the different recommendations. The majority of the

maturity models in (Malone et al., 2020) (13 out of

21) and in (Lacerda and von Wangenheim, 2018) (8

out of 11) use 5 levels of maturity, so we also used 5

levels. By giving descriptions to the different levels,

the participants have heuristics to assign recommen-

dations to a level.

We took the description of the levels from a study

by (Lacerda and von Wangenheim, 2018). In this

study, the authors identify eleven models, of which

four use the same scales, while the other seven use

scales that are all distinct. Three models in (Malone

et al., 2020) use the same scales as the four in (Lac-

erda and von Wangenheim, 2018). These are all ma-

turity models in the Software Development / Technol-

ogy domain. All other maturity models in (Malone

et al., 2020) use distinct names for the levels. The

common scales are shown in Table 1; we adapted the

descriptions to make them more generic.

Table 1: Common scale in Maturity Models, adapted from

(Lacerda and von Wangenheim, 2018).

Stage Description

1 – Initial No processes exist; work is

done according to the individ-

ual’s own preferences and ap-

proaches differ between applica-

tions

2 – Repeatable Work is done according to a re-

peatable approach which exists

in the employee’s mind

3 – Defined Work is done according to a doc-

umented procedure

4 – Managed Work is done according to a doc-

umented procedure and the pro-

cedure is evaluated and adapted

on a frequent basis to improve

efficiency and adaptability to

changes in the environment of

the work

5 – Optimising Data is gathered and used to im-

prove the efficiency and effec-

tiveness of the procedures

To reduce the complexity of prioritising the rec-

ommendations even further, we decided to cluster the

recommendations and only prioritise the recommen-

dations inside a cluster. To this end, we planned to let

the researchers and the staff from the telecommunica-

tions operator cluster recommendations according to

their business function. We named the resulting clus-

ters according to the business function and we named

these functions capabilities, Our intention was for the

A Cascade of Consequences: Improving an Accident Analysis Method by Learning from a Real Life Telecommunications Accident

65

subject matter experts to prioritise the different rec-

ommendations, taking into account that some recom-

mendations require that other recommendations are

implemented first. The subject matter experts would

then map all recommendations on the maturity scale

in Table 1, and that would define the priority of each

recommendation.

3.4 Review of the Diagrams

Drawing up the diagram is a lot of work: in our

previous case studies (Wienen et al., 2019; Wienen

et al., 2024), it took 2 or 3 workshops to complete

all 9 steps. We observed that efficiency is improved

by documenting the diagrams using a drawing tool

(draw.io) and sending digital copies out for review

between the different workshops. This enhancement

improves quality by introducing an additional online

review round, while also boosting efficiency by al-

lowing remarks to be processed offline. This, in turn,

avoids consuming valuable time from the subject mat-

ter experts.

4 ACCIDENT

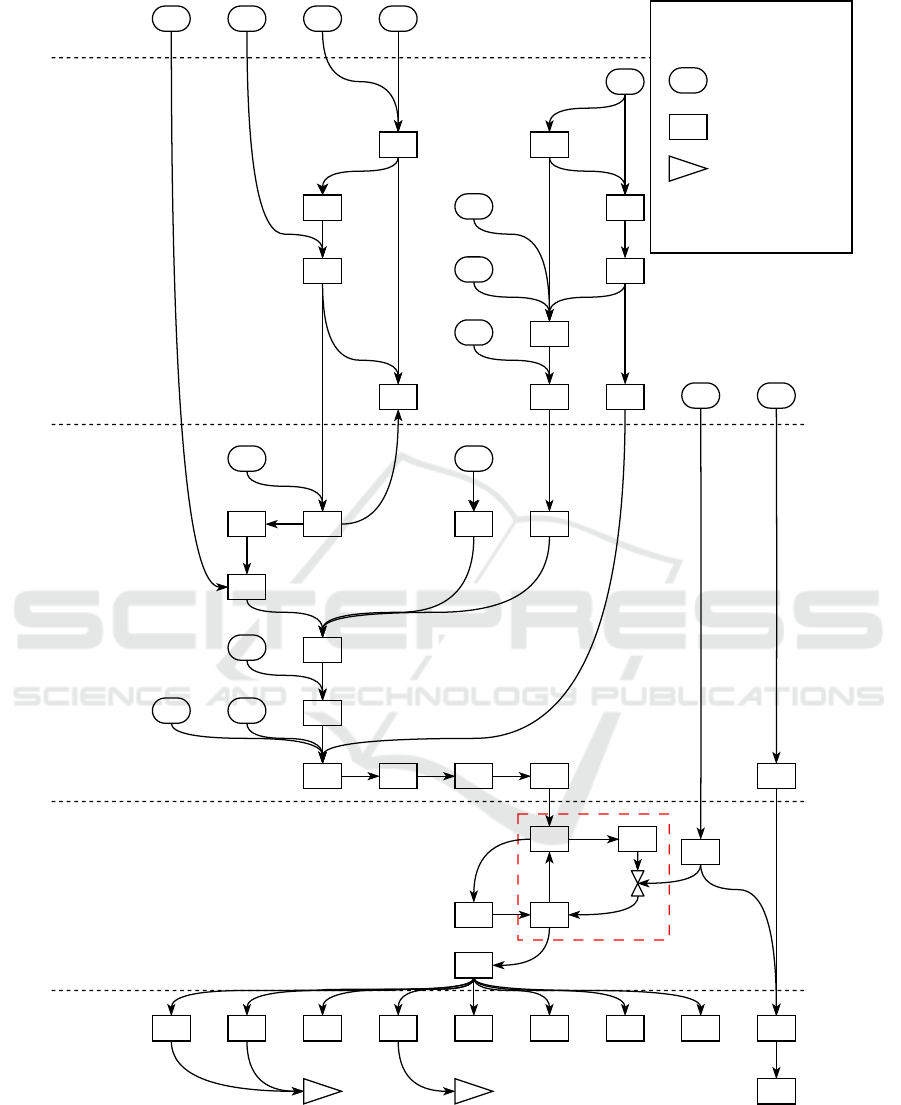

Due to the sensitive nature of the accident, we use

the pseudonym Gamma for the name of the com-

pany. Furthermore, some details have been left out

as they may reveal their identity. This is also the rea-

son why we use numbers instead of descriptive text in

the boxes in Figure 3.

4.1 Cause: Congestion

Sometime in 2018, Gamma virtualised a key com-

ponent of their network (an STP, or Signal Transfer

Point which is a routing device used to set up phone

calls). This device had been operational for a while

until Gamma needed to roll out a change in the de-

vice’s configuration. In preparation for this change,

Gamma created a snapshot (a backup) of the virtual

STP, so that a rollback could be executed in case any-

thing went wrong after the change.

During the creation of this snapshot, the virtual

STP became unresponsive for a few seconds. Dur-

ing this time, another network element (the HSS, or

Home Subscriber Server, which is the database that

contains information about subscribers and the ser-

vices they use) sent traffic to the STP that the STP

could not acknowledge. This caused a buffer over-

run in the HSS, resulting in a complete stop of the

HSS. Due to this stop, subscribers could no longer

access the network’s 4G service. Their devices then

switched to 2G and 3G all at the same time, while si-

multaneously trying to reach the 4G service, resulting

in a signalling storm that subsequently overloaded the

HSS and caused a complete loss of service.

Gamma resolved the issue by blocking access to

the network for all phones and then restarting the

HSS. By controlled release of the phones in small

batches, service could be restored. Figure 3 shows the

TRAM diagram of the accident. It includes the positive

feedback loop (# 40 – # 35 – # 38 – # 40) that caused

the congestion which resulted in the network break-

down (# 41). The triangles with A and B are connec-

tions to the diagrams that represent the consequences.

These diagrams are not included in this paper.

4.2 Consequence: Crisis

Gamma was not prepared for this crisis, since for bud-

getary reasons they had no centralised crisis commu-

nication organisation and no adequate tooling. Fur-

thermore, the Gamma staff only had Gamma sub-

scriptions for their phone, basically rendering the

whole organisation unable to communicate internally

during the first period of the crisis. The only available

channel for communication was a WhatsApp group,

severely hindering adequate communication during

the crisis.

Since company Gamma is the telecommunica-

tions service provider for the government and for

the hospitals of their country, communications within

the government broke down, and hospitals could no

longer be reached. The Ministry of Economic Affairs,

which was aware of the crisis before the company’s li-

aison was, held them to account. This led to further

reputation damage.

5 RESULTS OF THE ACCIDENT

ANALYSIS

We analysed the accident with TRAM in four work-

shops, namely two with technical staff and two with

communications staff, uncovering 91 causal factors,

leading to 65 outcomes. In the workshops, 265 rec-

ommendations the company could implement were

identified.

5.1 Feedback Loop

As shown in Figure 3, a feedback loop was instrumen-

tal in the breakdown of the network. Breaking that

loop enabled the company to restore service. Using

the notation we introduced in the previous case study

DATA 2024 - 13th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

66

External

Organisation

ICT

Physical / Actor

Outcomes

1 2 3 4

5

6 7

8

10

12

14

15

17

18

19 21

23

24 25

26

28

32

33

34

35

36 37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52

53A B

30

27

209

2922

16

13

11

31

Legend

x

y

start event - not

further analysed

event with

analysed cause

B

link to another

part of the

diagram (not

shown in this

paper)

Figure 3: TRAM diagram of the technical part of the accident.

(Wienen et al., 2024), we were able to model both the

feedback loop itself and the interruption of the feed-

back loop. The level of detail yielded recommenda-

tions for both the prevention and the interruption of

the feedback loop, thus validating and justifying the

notation.

A Cascade of Consequences: Improving an Accident Analysis Method by Learning from a Real Life Telecommunications Accident

67

5.2 Prioritisation by Maturity Level

After formulating the recommendations with the par-

ticipants of the workshops, we had a follow-up work-

shop with the company’s business continuity man-

agers. In this workshop, we clustered the recommen-

dations, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Clusters of recommendations.

Cluster description # recommen-

dations

Manage Communications 107

Manage Crisis 81

Manage Growth and Maturity 16

Manage Problem 10

Manage Reporting 1

Manage Resilience 44

Manage Resolution of Situation 6

We then asked the business continuity managers to

share the clustered recommendations with the partici-

pants in the workshops and ask them to order the rec-

ommendations according to dependence (which rec-

ommendations could be implemented right away, and

which were dependent on other recommendations that

needed to be implemented first) and according to ur-

gency (which recommendations needed to be imple-

mented as soon as possible and which could wait).

This information, together with the recommendation

itself, would enable us to plot them on the scale shown

in Table 1.

Unfortunately, the business continuity managers

were not able to incite the participants into complet-

ing this task, which prevented us from achieving these

specific results. For the same reason, we were not

able to formulate costs and benefits either. This il-

lustrates one of the difficulties frequently encountered

when applying TAR.

A way to circumvent this unresponsiveness of the

participants after the workshops are done is to en-

sure that the analysis has a sponsor at senior manage-

ment level. The results are aimed at improving the re-

silience of the company, thereby helping assure busi-

ness continuity. This is a responsibility of the board

and therefore senior management sponsorship can be

justified. Senior management can compel employees

to cooperate, while the business continuity managers

can only ask.

5.3 Splitting the Group According to

Expertise

The workshops started during the COVID-19 pan-

demic, when gatherings were prohibited, so we per-

formed our workshops online, using Microsoft Teams

and Excel to run the workshop. This had an impact on

efficiency, and the way the workshops were run was

not comparable to the previous workshops we con-

ducted, in which people gathered in a room around a

brown paper wall. This makes it impossible to draw

conclusions about efficiency with respect to splitting

the groups according to expertise.

We did notice, however, that in the workshops we

had a harder time making certain that ‘the other side’

(operations versus communications) was not blamed.

We did not observe the sharing of ideas between dif-

ferent areas of expertise in the workshops, unlike

what we saw in our previous case studies. In the

workshops of those case studies, the interaction led

to a common goal of learning from the accident on a

broader scale than just within individual departments.

6 DISCUSSION

In this section, we discuss the main lessons of our case

study.

Feedback Loop. Adding the notation for feedback

loops has two benefits:

1. It allows to represent one of the material causes of

the accident, giving more insight in the develop-

ment of the accident and possible ways to prevent

such a feedback loop from occurring at all.

2. It shows how the positive feedback loop can

be broken. Breaking the feedback loop gives

valuable recommendations for future accidents in

which this feedback loop plays a role. Identifying

its solution enables the organisation to draw up

step-by-step instructions for managing this type of

situation.

Prioritisation. We were not able to prioritise the

recommendations with company Gamma, as we never

received their feedback. We propose to involve se-

nior management to instruct staff to cooperate with

the analysis.

By identifying clusters of recommendation, we

were however able to formulate candidates for capa-

bilities that could be part of a maturity model. This

preliminary result needs to be validated in other case

studies.

DATA 2024 - 13th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

68

Splitting the Group According to Expertise. Al-

though we were not able to make a quantitative com-

parison of the efficiency of the meetings, we did ob-

serve that splitting the group along lines of expertise

removed a valuable aspect of the previous case stud-

ies: the sense of a common goal between different de-

partments and achieving an atmosphere in which the

principle of ‘no blame’ could be applied more easily.

However, due to the different circumstances in which

we conducted this case study as compared with our

previous study (Wienen et al., 2024), we cannot draw

general conclusions from this observation.

Threats to Validity. A threat to the validity of our

results is that these are the results of a single case

study (in the case of the notation for the positive feed-

back 2 case studies). The capabilities for telecom-

munications business continuity are drawn from the

recommendations, which, in turn, are a result of the

actual accident. Other accidents may yield different

capabilities.

Another threat to the validity is that the workshops

were conducted online due to COVID lock downs. It

is not possible to distinguish between the impact of

online working and the effect of splitting up the group

according to expertise.

7 FINAL REMARKS

In this paper, we discussed the application and en-

hancements of TRAM, which is a method for analysing

accidents initially targeted to the telecommunications

domain. In our research, we observed that by ex-

plicitly representing feedback loops we could identify

areas that run the risk of starting a cascade of con-

sequences in a positive feedback loop, causing even

more damage to the organisation.

We observed that splitting the group according to

expertise is counterproductive and we identified busi-

ness capabilities that may form a basis for a matu-

rity model for business continuity for telecommuni-

cations. Furthermore, we proposed to obtain a spon-

sor at senior management level to ensure cooperation

from the organisation.

Further research into capability maturity models

for Business Continuity Management can give new

insights into ways to prioritise recommendations. Fit-

ting the recommendations for crisis management to

a crisis management framework may also give new

insights into prioritisation. Our clustering of recom-

mendations can be seen as a first proposal for the ca-

pabilities needed for business continuity for telecom-

munication companies, both from the aspects of pre-

venting an accident that threatens business continu-

ity and from the aspect of crisis management. The

adequacy of the clusters and their applicability as a

means for prioritising recommendations also merits

further research. Future research can also apply ad-

vanced data analytics to the analysis of the recom-

mendations, such as clustering techniques based on

NLP for discovering new capabilities. Finally, future

research may show the effect of senior management

level involvement on the prioritisation of the recom-

mendations and staff involvement.

REFERENCES

Branford, K., Naikar, N., and Hopkins, A. (2009). Guide-

lines for accimap analysis. In Hopkins, A., editor,

Learning from High Reliability Organisations, chap-

ter 10. CCH Australia Ltd.

Hollnagel, E. (2002). Understanding accidents-from root

causes to performance variability. In IEEE 7th Human

Factors Meeting, pages 1–1 – 1–6. New Century, New

Trends. Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE 7th Conference

on Human Factors and Power Plants.

Hollnagel, E. and Goteman, O. (2004). The functional res-

onance accident model. Proceedings of cognitive sys-

tem engineering in process plant, 2004:155–161.

Junttila, J. (2014). A Business Continuity Management Ma-

turity Model. Master’s thesis, University of Turku.

Lacerda, T. C. and von Wangenheim, C. G. (2018). System-

atic literature review of usability capability/maturity

models. Computer Standards & Interfaces, 55:95–

105.

Leveson, N. (2004). A new accident model for engineering

safer systems. Safety Science, 42(4):237–270.

Mahal, A. (2008). Business Continuity Management Matu-

rity Model for Banks in U.A.E. Master’s thesis, The

British University in Dubai.

Maier, A. M., Moultrie, J., and Clarkson, P. J. (2012).

Assessing Organizational Capabilities: Reviewing

and Guiding the Development of Maturity Grids.

IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management,

59(1):138–159.

Malone, N., Hernandez, M., Reardon, A., and Liu, Y.

(2020). Advanced Distributed Learning Capability

Maturity Model. Technical report, US Department of

Defense — Defense Human Resource Activity.

Rasmussen, J. (1997). Risk management in a dynamic soci-

ety: a modelling problem. Safety science, 27(2):183–

213.

Reason, J. (1990). The contribution of latent human failures

to the breakdown of complex systems. Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Bio-

logical Sciences, 327(1241):475–484.

Reis, T. L., Mathias, M. A. S., and Oliveira, O. J. d. (2017).

Maturity models: identifying the state-of-the-art and

the scientific gaps from a bibliometric study. Sciento-

metrics, 110(2):643–672.

A Cascade of Consequences: Improving an Accident Analysis Method by Learning from a Real Life Telecommunications Accident

69

Salmon, P., Goode, N., Lenne, M., Finch, C., and Cassell,

E. (2012). Understanding accident causation in led

outdoor activities: development of an accident anal-

ysis framework. Injury Prevention, 18(Supplement

1):A240–A240.

Smit, N. (2005). Business Continuity Management - a Ma-

turity Model. Master’s thesis, Erasmus University

Rotterdam.

Vesely, W. E., Goldberg, F. F., Roberts, N. H., and Haasl,

D. F. (1981). Fault tree handbook. Technical Report

0492, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Wienen, H. C. A., Bukhsh, F. A., Vriezekolk, E., Fer-

eira Pires, L., and Wieringa, R. J. (2024). Squeez-

ing the lemon: Using accident analysis for recom-

mendations to improve the resilience of telecommu-

nications organizations. Accepted for publication in

ICEIS 2024.

Wienen, H. C. A., Bukhsh, F. A., Vriezekolk, E., and

Wieringa, R. J. (2018). Learning from accidents: A

systematic review of accident analysis methods and

models. International Journal of Information Systems

for Crisis Response and Management (IJISCRAM),

10(3):42–62.

Wienen, H. C. A., Bukhsh, F. A., Vriezekolk, E., and

Wieringa, R. J. (2019). Applying generic AcciMap to

a DDoS attack on a Western-European telecom oper-

ator. In Proceedings of the 16th ISCRAM Conference,

pages 528–535.

Wieringa, R. J. (2014). Design Science Methodology

for Information Systems and Software Engineering.

Springer.

DATA 2024 - 13th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

70