Kex-Filtering: A Proactive Approach to Filtering

Fabrizio Baiardi

1 a

, Filippo Boni

1 b

, Giovanni Braccini

1 c

, Emanuele Briganti

2

and Luca Deri

1,3 d

1

Dip. di Informatica, Universita di Pisa, Largo Bruno Pontecorvo, Pisa, Italy

2

ReeVo Cloud & Cyber Security, Italy

3

Ntop, Italy

Keywords:

IP Blacklist, Hash, Botnet, Hassh, SSH Configuration, Honeypot, Network Fingerprint.

Abstract:

Kex-Filtering is a method to identify malicious nodes by analyzing their configuration when they try to connect

as clients to an SSH server. The process adopts the hassh hashing network fingerprinting standard to discover

and record the distinct configurations of malicious SSH clients. The method computes an MD5 hash during

the SSH handshake when the client and server exchange their SSH configurations, including a specific range of

algorithms to establish a secure SSH channel. Kex-Filtering fully exploits that, to simplify botnet management,

a large number of nodes of a botnet share the same configuration of their SSH clients. Experimental data

collected through honeypots confirm that Kex-Filtering stops a large percentage of attacks and it results in a

very low number of false positives and negatives even when using few hashes.

1 INTRODUCTION

IP blacklists are the most popular method to iden-

tify and block SSH attacks. One of its weaknesses

is low effectiveness against rapidly expanding large-

scale botnets that continually evolve and add new

nodes. It is challenging to continuously update con-

ventional IP blacklists to keep pace with the rapid

evolution and extension of botnets.

This paper introduces Kex-Filtering, a new

method to identify attacks from a botnet. Its defini-

tion is based on data we have collected in 8 months

from 4 honeypots in the Azure and the AWS data cen-

tres. The honeypots have been the targets of more

than 20,000 attacks where 98.5 per cent of these at-

tacks were automated and most were produced by

botnets categorized as Mirai-like, the new generation

of botnets leverages derivative or enhanced Mirai-like

code that does not rely on compromised IoT devices

or other vulnerable systems only. According to our

data, libssh 4 was the most common client finger-

print in SSH attacks, accounting for over 65 per cent

of total incidents. This led us to define and evalu-

ate Kex-Filtering, an approach to identify malicious

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9797-2380

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3433-4469

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-2013-7233

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8084-1667

nodes based on a fingerprint of the SSH client config-

urations in these nodes. This approach to discovering

connections from botnet nodes largely differs from

conventional IP-filtering methods because it does not

use a blacklist of IP addresses to filter incoming SSH

connections. Instead, Kex-Filtering analyzes the con-

figuration of the client connecting to the SSH server

and compares it against known malicious configura-

tions. A successful comparison implies that the client

belongs to a botnet. Experimental results confirm that

Kex-Filtering is much more effective than traditional

IP blacklists because even a small blacklist with less

than 15 patterns can block up to 98.5 per cent of at-

tackers with a very low number of false positives.

Furthermore, the proposed solution is proactive be-

cause it filters out an IP address autonomously, upon

discovering it is configured maliciously. Lastly, Kex-

Filtering detects an attack as soon as the TCP hand-

shake is completed, effectively preventing the attacker

from executing malicious commands. This can stop

and identify attacks at the root.

Kex-Filtering should be seen as an integration

rather than as a replacement for standard IP blacklists

as it adds to filtering the capability to dynamically up-

date an IP blacklist with the addresses of those hosts

that match known malicious client configurations. In

this way, Kex-Filtering not only blocks connections

from these IPs but, as confirmed by the data we have

collected, it strongly simplifies the identification and

528

Baiardi, F., Boni, F., Braccini, G., Briganti, E. and Deri, L.

Kex-Filtering: A Proactive Approach to Filtering.

DOI: 10.5220/0012788700003767

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT 2024), pages 528-535

ISBN: 978-989-758-709-2; ISSN: 2184-7711

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

blacklisting of SSH attackers, particularly those using

nodes belonging to botnets.

We review related work in Sect.2. The following

sections describe, respectively, the architecture of the

honeypots to collect data and how the analysis of the

data collected by our honeypots has suggested the def-

inition of Kex-Filtering. Sect. 5 describes the experi-

ments we have run to evaluate Kex-Filtering and then

Sect. 6 compares its performances against the one of

IP blacklists. The last section outlines future works.

2 RELATED WORKS

Previous work has suggested adopting a filtering

mechanism based on duplicate hashes. This includes

(Gasser et al., 2014) that has used the results of a mas-

sive internet scan implemented in 2013 and (Byth-

wood et al., 2023) but they do not evaluate the ef-

fectiveness of the adoption of duplicate hashes. (Du-

launoy et al., 2022) uses SSH hashes to classify SSH

servers rather than to identify botnets. Also (Heino

et al., 2022) outlines the feasibility of filtering based

on hashes but it is focused on web applications. The

number of hashes collected in (Shamsi et al., 2022) is

too low to result in effective filtering. Our work gener-

alizes the solutions previously proposed (Heino et al.,

2023) and it includes a performance evaluation of the

adoption of hassh filtering to discover malicious SSH

connections. The performance evaluation is built on

the large amount of data the honeypots have collected.

An alternative method for SSH fingerprinting is

JA4SSH (Foxio, 2024). While hassh aims to fin-

gerprint SSH applications, JA4SSH focuses on fin-

gerprinting SSH sessions by analyzing the encrypted

traffic exchanged during the connection. Even this

fingerprint may detect attack patterns and behaviours

but this paper will primarily focus on the adoption of

the hassh fingerprinting to discover malicious nodes

before they can implement an attack.

The deployment of honeypots in clouds has been

previously examined. Earlier research (Kelly et al.,

2021) has explored the correlation between the popu-

larity of cloud providers and the frequency of attacks.

Unlike studies focused on popularity, currently the

adoption of honeypots shifts its emphasis to a more

security-centered approach. A similar shift can be ob-

served in the recent work by Orca Security (Security,

2023). They deployed honeypots storing cloud access

keys across multiple providers and measured the in-

terval from deployment to the discovery and exploita-

tion of the keys.

3 HONEYPOTS FOR DATA

COLLECTION

The definition of Kex-Filtering has been suggested

by the analysis of data collected by a set of honey-

pots. We have used four honeypots, two of which

were hosted on AWS and the other two on Azure

cloud. The resulting dataset spans 8 months and in

these months more than 20000 distinct IPs of attack-

ers have produced more than 400000 attacks.

All these honeypots used Cowrie (Oosterhof,

2015) a medium-interaction honeypot and supported

the SSH protocol. Furthermore, for further investiga-

tions, in one honeypot on each cloud, we configured

the Dionaea low-interaction honeypot citesethia2019

for multi-protocol support.

Table 1: Deployment Details of the Honeypots.

Honeypot Cloud Plt. Protocols

Azure A Azure SSH, FTP, SMB, HTTP

Azure B Azure SSH

AWS A AWS SSH, FTP, SMB, HTTP

AWS B AWS SSH

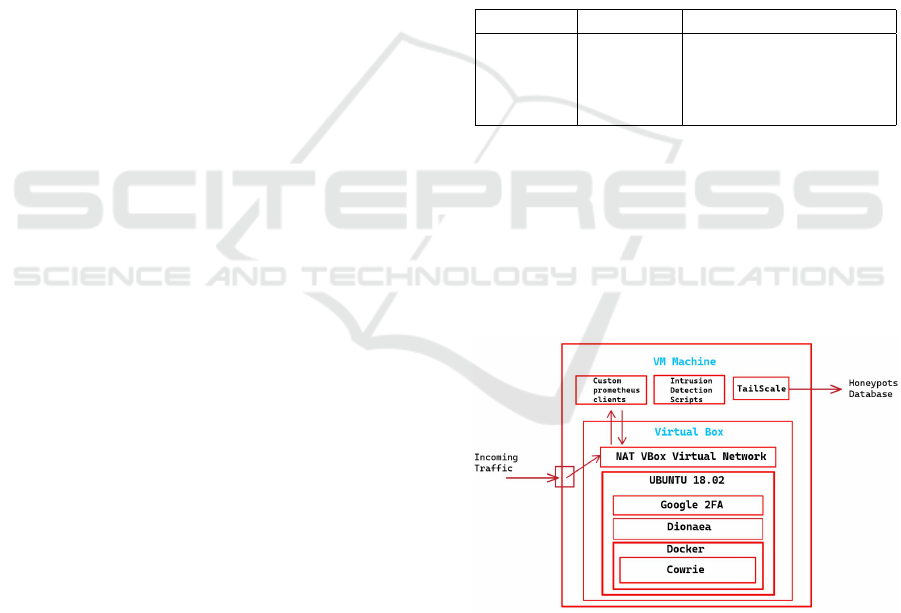

Each honeypot server exploits both virtual ma-

chines (VMs) and Docker containers (Inc., 2013) to

build a scalable and isolated environment where VMs

act as protective barriers between the network and

the hosted honeypots. We have used this solution to

effectively confine potential security breaches within

the containers themselves, thereby preserving the host

system’s integrity.

Figure 1: Architecture of the Honeypot Machine.

To improve the robustness of our honeypots, each

one also includes a sophisticated alert system that ac-

tivates immediately when access is granted to either

the host or the virtual machine. In addition, we have

deployed a protective protocol to suspend the oper-

ations of either the Docker container or the VM as

soon as an unauthorized login is attempted. To se-

Kex-Filtering: A Proactive Approach to Filtering

529

cure access to the VMs themselves, we have hardened

them with a two-factor authentication (2FA) system.

For real-time monitoring and time-series data analy-

sis, we have integrated the Prometheus

1

time-series

database with our VMs and honeypots using custom

scripts. In this way, we can measure not only log data

but the environment metrics of the VMs too. Lastly,

since Prometheus is primarily a metric collection tool,

we have paired it with Grafana

2

for data visualiza-

tion. (Labs, 2021).

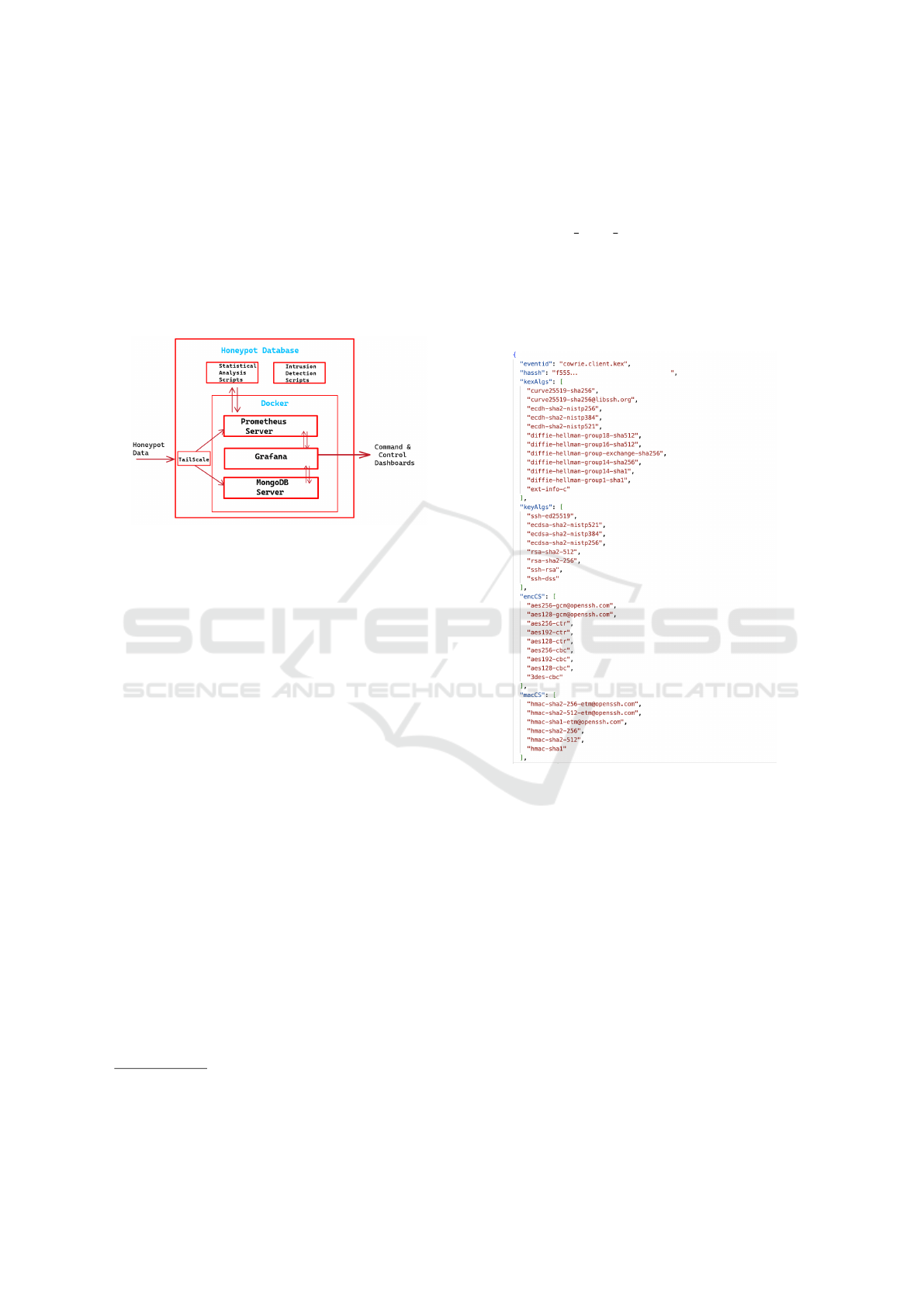

Figure 2: Honeypot Server Architecture.

Each honeypot securely transmits the data it col-

lects to a server (see Fig. 2) hosting both Prometheus

and MongoDB through the Tailscale network

3

for en-

hanced privacy and security.

The integration of Tailscale, for safe data transfer-

ring, Prometheus for time series generation, Grafana

for data visualization, and MongoDB for efficiently

storing the dataset for finer-grained analysis, results

in a robust and secure ecosystem for collecting, stor-

ing, and analyzing honeypot data.

4 FINGERPRINTING BOTNETS

This section describes Kex-Filtering in some detail,

starting from the fingerprinting of the configuration

of some botnet nodes.

4.1 Hash Fingerprinting

We have adopted the hassh hashing method to fin-

gerprint and record the configurations of SSH clients.

This method generates a unique MD5 hash for a spe-

cific combination of the encryption algorithms the

client supports. The hash is computed during the SSH

handshake and after the initial TCP three-way hand-

shake when the client and server exchange their SSH

1

https://prometheus.io

2

https://www.grafana.com/

3

https://tailscale.com

configurations as shown in Fig. 3. One of the data the

client and the server exchange is the list of supported

algorithms that play a crucial role in establishing a

secure SSH channel. These configurations are trans-

mitted via SSH MSG KEXINIT packets in clear text.

We use the algorithms in the list and their transmis-

sion order to produce a fingerprint to identify partic-

ular client applications or their unique setups (Sales-

force, 2018). We refer to this aspect of the SSH pro-

tocol as KEX (key exchange), and henceforth, hassh

hashes will be denoted as ”KEX hashes”.

Figure 3: Some Information the SSH Handshake Ex-

changes.

The data our honeypots have collected confirms

that attacks from distinct nodes sharing the same hash

apply nearly identical strategies and execute the same

commands. This suggests that nodes within the same

botnet are usually configured with the same SSH

client and hence they have the same KEX hashes.

Consequently, the KEX hash can detect attacks from

all the nodes from the same botnet.

This method has identified one of the most domi-

nant botnets. This botnet is linked to the Outlaw crim-

inal gang and it includes more than 8000 IP addresses

that have attacked our honeypots. It is responsible for

more than 48 per cent of the attacks against the bot-

nets we have deployed.

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

530

4.2 Kex Hashes Distribution

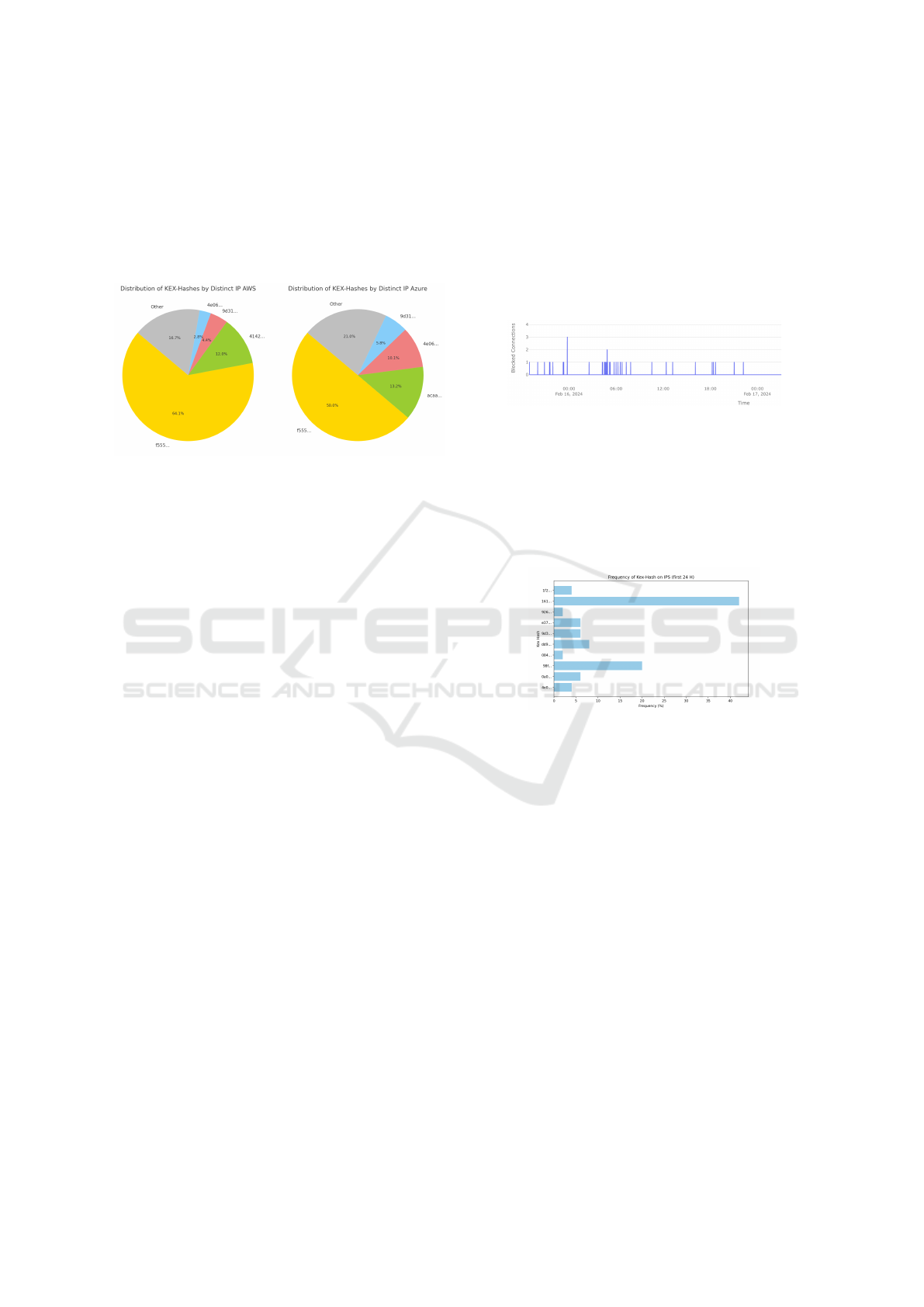

We show the effectiveness of Kex-Filtering through

the HASSH hashes produced by the four previously

described honeypots.

Figure 4: Top 3 KEX hashes in Azure & AWS

As shown in Fig. 4 the top three KEX hashes

cover 94 per cent of attacks in the AWS dataset and

approximately 90 per cent of those in the Azure one.

We also notice that 70 per cent of the attacks against

Azure share the same KEX hash (Hash 1).

This confirms the potential of Kex-Filtering, as

it succeeds in blocking about 92 per cent of attacks

when using just 3 KEX Hashes. Our dataset included

about 100 unique KEX hashes collected across both

cloud providers. This is a much smaller dataset than

one storing attacking IPs (over 20000). It is also

smaller than a standard IP blacklist.

Figure 5: Distribution of KEX hashes Across Providers.

Fig. 5 shows the hashes distribution with a large

intersection between the KEX hashes collected by

the honeypots in the two clouds. The intersection

among attack vectors across the two clouds confirms

that Kex-Filtering identifies the same botnets in both

clouds.

After discovering the similarity in KEX hash dis-

tributions for both clouds, we have merged and ana-

lyzed the two datasets. The resulting bar chart shows

the top 15 KEX hashes for the overall data and their

prevalence as a percentage of total occurrences in

both environments.

The data in Fig. 6 shows the striking prevalence

of just one KEX hash that is identified by its initial se-

quence ”f555...”. This hash is remarkably widespread

for both cloud providers. According to our dataset,

about 63 per cent of the SSH attacks on our honeypots

Figure 6: Top 15 KEX hashes in Azure & AWS.

in the two environments are associated with this hash.

The prominence of this single KEX hash offers a sig-

nificant opportunity for mitigating the largest fraction

of these attacks. The adoption of a filter that only tar-

gets this hash could potentially neutralize up to 63 per

cent of SSH attacks. This confirms the effectiveness

of Kex-Filtering. The outcomes of our analysis fur-

ther support this effectiveness because a concise set

of just 15 blacklisted hashes can discover and block

98.5 per cent of the SSH attacks in the dataset.

4.3 Effectiveness of KEX Hashes

The collected data reveals the strikingly limited num-

ber of KEX hashes that are used. This observa-

tion suggested an investigation into the underlying

reasons, building upon our analysis of the OutLaw

Crypto-Botnet’s source code. As already mentioned,

several botnets, notably those based on the Mirai

source code, mostly use the same attack code and

therefore use the same SSH clients with the same con-

figuration. This shared configuration simplifies the at-

tacker tasks because the creation of a distinct configu-

ration for each botnet node is much more complex and

expensive. This implies that a large number of botnet

nodes share the same KEX hash and that botnets us-

ing similar, unchanged codes can be readily identified

through their KEX hashes.

Figure 7: Percentage of Attackers with OutLaw KEX hash.

The widespread use of the KEX hash ’f555’ has

been directly linked to attacks attributed to the Out-

Law botnet. The correlation of IP addresses identified

as OutLaw nodes and those using the ’f555’ hash con-

firms that no node identified through Kex-Filtering is

Kex-Filtering: A Proactive Approach to Filtering

531

a false positive and all the nodes are actual members

of an operating botnet. This confirms that the pro-

posed method can discover malicious nodes and iden-

tify the botnet they belong to. This information may

be essential to fully exploit information from threat

intelligence about possible attackers and their TTPs

(Xiong et al., 2022)

Figure 8: Distribution of Unique IP per Hash.

Fig. 8 shows the distribution of unique IPs as-

sociated with each KEX hash. Notably, the hash

beginning with ’f552’ emerges as the predominant

choice among attackers, consistent across all cloud

providers. Remarkably, the five hashes in the graphs

jointly represent about 82 per cent of the attackers

when considering both Azure and AWS. This shows

that by filtering just these five KEX hashes, Kex-

Filtering can both detect and block in the initial stages

of the SSH handshake nearly all malicious actors tar-

geting the SSH protocol.

5 EXPERIMENTAL EVALUATION

Building upon the preliminary results previously de-

scribed, this section investigates the practical applica-

tion of Kex-Filtering.

To achieve a robust evaluation, we have developed

a standalone system independent of the one to collect

hashes. This avoids any bias due to the evaluation set-

up.

The system we have developed is a custom rule-

based intrusion prevention system (IPS) that corre-

lates the KEX hashes of connecting clients with the

repository of hashes collected by our honeypots. As

soon as the IPS discovers a hash match within the

dataset, ie a potentially malicious connection, it im-

mediately stops the SSH handshake. Furthermore,

in response to a KEX hash match, the IPS dynami-

cally updates an IP blacklist to block traffic originat-

ing from the corresponding host not only on SSH but

across all the services.

5.1 Performance Analysis

We ran the IPS for two days using the most significant

50 hashes from the honeypot data. The decision to

increase the number of hashes from the original 15

hashes is due to the distinct network environment

under test. This test, even if very short, has produced

some insights into the effectiveness of the proposed

method.

Figure 9: Timeline of Blocked Connections by Kex-

Filtering.

In total, the IPS was targeted by 202 SSH connec-

tions. During the first 24 hours, the system effectively

blocked 99.5 per cent of attempted attacks, 52 con-

nections out of 53. Remarkably, just 2 of these hashes

have accounted for over 60 per cent of the blocked

attackers (as shown in Fig: 10)

Figure 10: Hits Distribution in Blacklisted Hashes (first

24h).

The bar chart in Fig: 10 shows that in the first 24

hours, our IPS works at the expected rate. It also con-

firms that KEX-Filtering is effective even when it uses

few hashes.

The effectiveness has a drastic drop in the next 24

hours, as it blocks just a mere 35 per cent of the mali-

cious traffic (14.8 per cent blocked in these 24 hours).

The reduced effectiveness is due to a data shift be-

cause our honeypots collected the data three months

before we deployed the IPS. In the elapsed months,

new botnets with fresh KEX hashes have emerged and

one of them has targeted our IPS (Quinonero-Candela

et al., 2009), (Storkey, 2009).

In particular, on the second day, the IPS was tar-

geted by a new swarm of attacks identified by a KEX

hash beginning with ”aca”. This source of attacks

uses distinct IP addresses for each connection.

The usage of distinct IP addresses with the same

KEX hash strongly suggests the attacker operates

through a botnet. This confirms that nodes with the

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

532

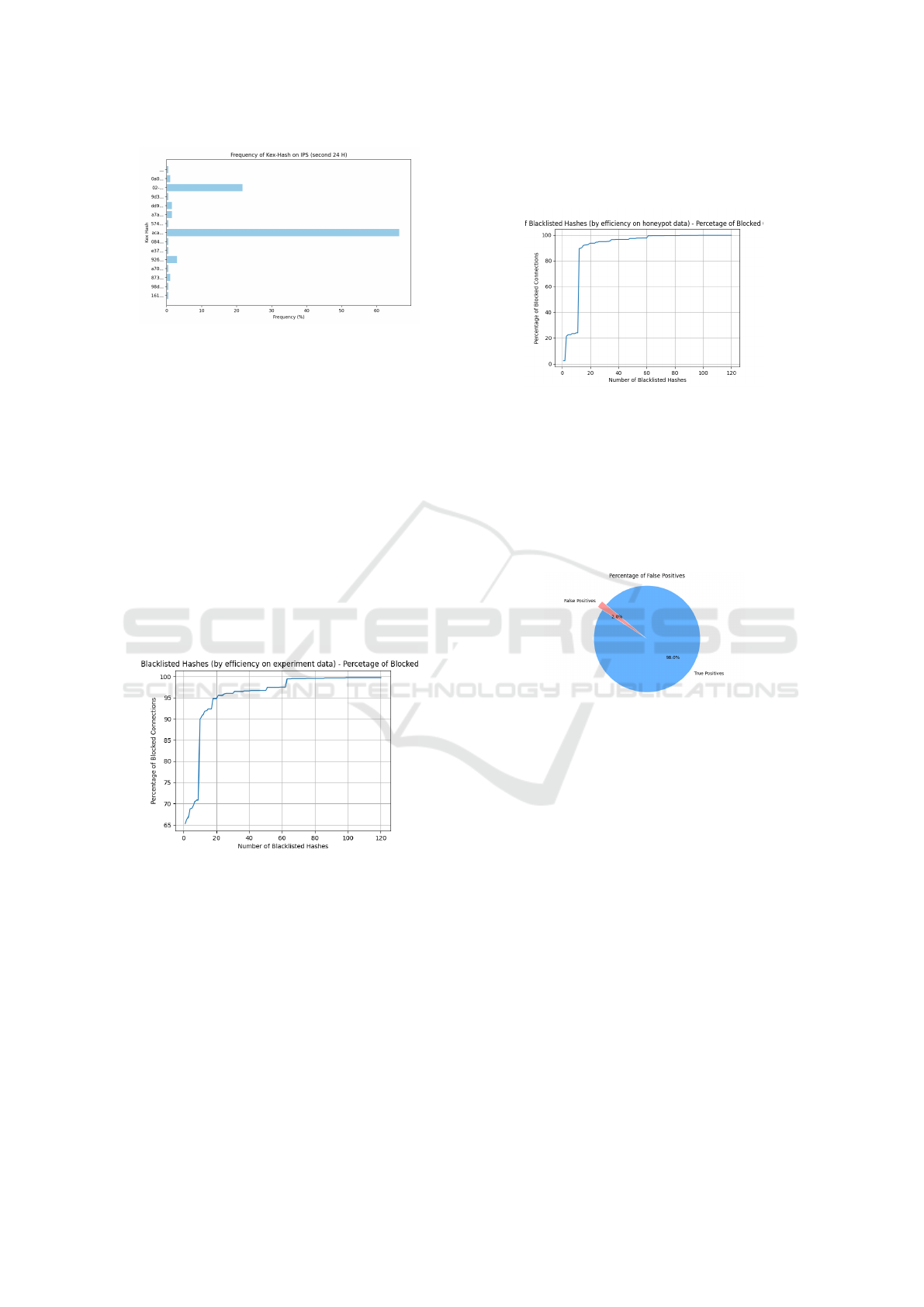

Figure 11: The Hashes Observed by the IPS (second 24h).

same KEX hash belong to the same botnet and it

validates the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Moreover, it also confirms the effectiveness of Key-

Filtering even when using a small set of hashes pro-

vided that this set is dynamically updated to cover

new botnets.

A possible solution uses honeypots to gather new

data that is used to continuously update the IPS sys-

tems about new botnets.

The next analysis shows how the blocking rate of

the proposed method correlates with the number of

used KEX hashes. It confirms that even when Key-

Filtering uses just a few entries, it can stop most of the

attackers blocked by the whole hash list. This high-

lights the effectiveness of Kex-filtering even with a

small list.

Figure 12: Blocking Rate as a Function of KEX Hashes.

Fig. 12 shows how the blocking rate of the IPS we

have developed changes depending on the number of

hashes present in the blacklist it uses. In this chart, the

KEX hashes are arranged by their effectiveness in the

experiment. We observe that when Kex-Filtering em-

ploys just a single hash (the first point on the chart),

the percentage of blocked connections jumps to 65%.

This points out that in the 48 hours of activity, a sig-

nificant percentage of the attackers that Key-Filtering

blocks come from the same botnet. If we move to

the right on the x-axis of the graph, we see that when

Key-Filtering uses about 20 hashes its effectiveness is

close to a horizontal line in the two days. The next

chart shows the same data as in Fig. 12, but now

the data are structured according to the popularity of

KEX hashes leveraging historic honeypot data:

Figure 13: Blocking Rate vs the Number of Hashes.

Fig. 13 shows the performance of the first entries

of the blacklist, ordered by efficiency on the honeypot

data. Initially, the performance of these entries is not

satisfactory but the inclusion of less than 20 additional

entries results in a remarkable surge in performance,

reaching a block rate of 90%. This suggests that the

hash of the botnet targeting our honeypot was eventu-

ally added to the blacklist.

Figure 14: Percentage of False Positives.

According to Fig 14, just 2% of the collected Kex

hashes belong to benign ssh clients (myceliumbroker,

2024). This shows that Kex-Filtering can effectively

identify malicious SSH clients, as it successfully dis-

tinguishes them from benign ones. In fact, none of

the hashes in the blacklist for this test belongs to well-

known benign SSH clients.

5.2 Auto-Learning Hashes

We investigate the usage of KEX hashes identified as

malicious in some days to create a dynamic list of

hashes to be used the next day. This could result in

a highly effective setup of Kex-Filtering. The only

problem to be considered in a production server envi-

ronment is due to false positives. We mitigate this

problem by defining a whitelist of IP addresses to

avoid blocking known good hashes.

This experiment considered the hashes collected

in the previous days as malicious because the node

running the IPS is never accessed by a non-malicious

actor.

Kex-Filtering: A Proactive Approach to Filtering

533

The analysis presented here is based on a week-

long deployment of the IPS on the same machine used

for the analysis previously described.

Figure 15: Blocked Attackers as a Function of Training.

Fig. 15 shows how the number of training days

affects the percentage of attacks blocked on the fol-

lowing day. According to these results, the data col-

lected in just one day results in an effectiveness rate

on the following day of about 95 per cent, The ef-

fectiveness steadily increased to full protection (100

per cent) when using the previous four days as train-

ing. However, on the fifth day, efficiency decreased

to 70 per cent. This may be due to a new botnet that

was idle in the previous days, as in previous analy-

ses. Despite this, the effectiveness of Key-Filtering

consistently remains very high.

6 KEX-FILTERING VS IP

BLACKLISTS

This section compares the performance of our solu-

tion against the one of state-of-the-art IP blacklists.

This experiment has compared the performances of

the two solutions in the two days of deployment.

6.1 Configuring the Solutions

We have considered three types of IP blacklists: a

daily blacklist based on the IPs observed in the pre-

vious 24 hours, and two historical blacklists that also

consider previous malicious IPs. These two lists

are the ”Alpha” IP Blacklist and the more complete

”Alpha 7” blacklist that, on average, includes about

54,700 IPs. We used open-source blacklists produced

by the Stratosphere Lab.

4

.

On each day, we extracted the attackers’ IPs and

cross-referenced them against the IP blacklist for the

same day.

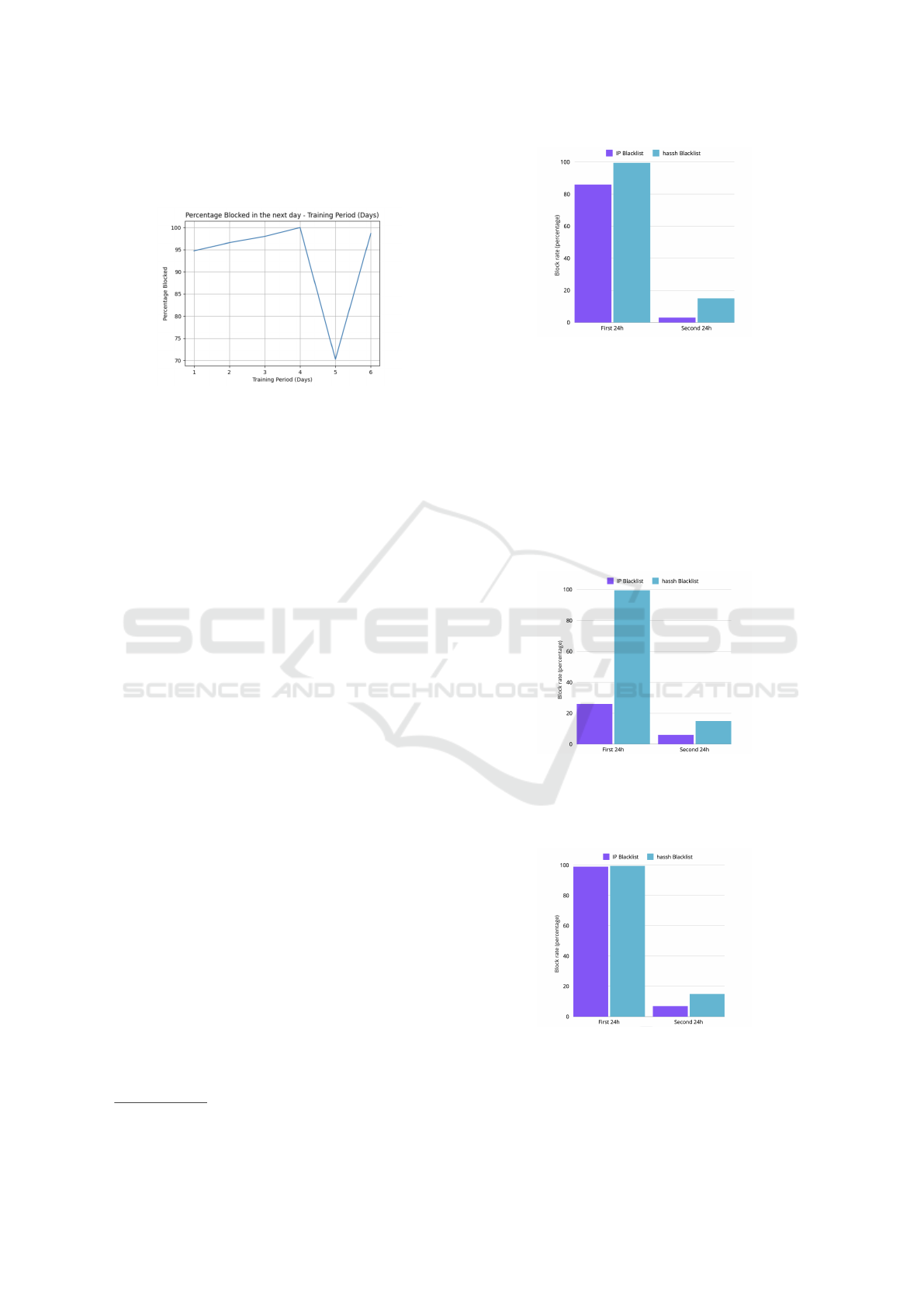

Fig. 16 shows that on the first day, the IP Black-

list blocks over 80 per cent of the attackers, while

4

https://www.stratosphereips.org

Figure 16: Blocking rate of Daily IP Blacklist vs Kex-

Filtering.

Kex-Filtering blocks 99.5 per cent of the attackers.

These percentages take into account that the deploy-

ment started at 7 PM while the blacklist we have used

covers three consecutive days.

On the second day, the IP blacklist only blocks 3

per cent of attackers, just 2 out of 67 IPs, whereas

Kex-Filtering blocked 14.8 per cent of malicious

connections. Despite its large performance decline,

because of the reasons previously explained, Kex-

Filtering is still more effective than IP blacklist.

Figure 17: Blocking rate of AIP Alpha vs Kex-Filtering.

Kex-Filtering results in a better performance

while the IP blacklist blocked very few attackers, even

when using it in the next 24 hours.

Figure 18: Blocking Rate of AIP Alpha7 vs Kex-Filtering.

These IP blacklists include more than 54,700 en-

tries. In the first 24 hours, their performance and the

one of Kex-Filtering are similar as they both detected

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

534

almost any attackers. However, on the second day,

despite its size, the IP blacklist only blocks 7.3 per

cent of malicious traffic, while Kex-Filtering blocks

about 14.7 per cent of the same traffic. As already

discussed, the under-performance of the IP blacklist

may be due to a new botnet it did not include.

6.2 Overall Evaluation

Our experimental evaluation confirms the better per-

formance of Kex-Filtering provided that we adopt the

same update strategy of IP blacklists. As an exam-

ple, developments (Deri and Fusco, 2023) show that

a solution that merges the six most popular file-based

IP blacklists discovers less than 50 per cent of attack-

ers. Furthermore, current botnets such as the OutLaw

defeat conventional IP blacklists by launching attacks

from new hosts as they expand. Instead, evading Kex-

Filtering is more challenging because this requires up-

dating the SSH clients in the current botnet nodes with

a large overhead due to the sheer volume of botnet

nodes. Even the adoption of distinct SSH client con-

figurations for each victim node is highly complex as

it requires a large and diverse set of configurations

that should be properly managed. This results in a

large overhead for the botnet owner. Instead, Kex-

Filtering only requires a check against a small dataset

of hashes where each hash can block attacks from sev-

eral nodes. This enhances efficiency and it strength-

ens the defence against a broader range of attackers.

This is in stark contrast to IP blacklist which usually

involves tens of thousands of entries (i.e. the Alpha7

blacklist includes more than 54700 IPs), where each

one blocks attacks from a single host only. Further-

more, IP blacklists usually have a short life because

of the volatile nature of IP addresses. Instead, the life

of Kex hashes should be as long as one of the cur-

rent botnet nodes, offering reliable identification and

filtering with a low rate of false positives.

7 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

Our experimental evaluation confirms the effec-

tiveness of Kex-Filtering a simpler technique than

IP filtering. However, given their relative merits,

we plan to integrate Kex and IP filtering to define

a more comprehensive solution for mitigating and

detecting attackers. A first example is the simple

IPS previously described that uses the output of

Kex-Filtering to update IP blacklists.

REFERENCES

Bythwood, W., Kien, A., and Vakilinia, I. (2023). Finger-

printing bots in a hybrid honeypot. pages 76–80.

Deri, L. and Fusco, F. (2023). Evaluating ip blacklists ef-

fectiveness.

Dulaunoy, A., Huynen, J.-L., and Thirion, A. (2022). Ac-

tive and passive collection of ssh key material for cy-

ber threat intelligence. Digital Threats: Research and

Practice, 3(3):1–5.

Foxio (2024). JA4+ Network Fingerprinting. https://blog.f

oxio.io/ja4\%2B-network-fingerprinting.

Gasser, O., Holz, R., and Carle, G. (2014). A deeper un-

derstanding of ssh: Results from internet-wide scans.

In 2014 IEEE Network Operations and Management

Symposium (NOMS), pages 1–9.

Heino, J., Gupta, A., Hakkala, A., and Virtanen, S. (2022).

On usability of hash fingerprinting for endpoint appli-

cation identification. pages 38–43.

Heino, J., Hakkala, A., and Virtanen, S. (2023). Categoriz-

ing tls traffic based on ja3 pre-hash values. Procedia

Computer Science, 220:94–101. 14th Int. Conf. on

Ambient Systems, Networks and Technologies Net-

works (ANT).

Inc., D. (2013). Docker: Empowering app development for

developers. https://www.docker.com.

Kelly, C., Pitropakis, N., Mylonas, A., Mckeown, S., and

Buchanan, W. (2021). A comparative analysis of hon-

eypots on different cloud platforms. Sensors, 21.

Labs, G. (2021). Grafana: The open observability platform.

Accessed: 2023-07-29.

myceliumbroker (2024). Hassh clients dataset.

Oosterhof, M. (2015). Cowrie ssh/telnet honeypot.

Quinonero-Candela, J., Sugiyama, M., Lawrence, N., and

Schwaighofer, A. (2009). Dataset Shift in Machine

Learning. MIT Press.

Salesforce (2018). Hassh: A network fingerprinting stan-

dard for ssh. https://github.com/salesforce/hassh.

Security, O. (2023). Orca security ‘2023 honeypotting in

the cloud report’ reveals attackers weaponize exposed

cloud secrets in as little as two minutes.

Shamsi, Z., Zhang, D., Kyoung, D., and Liu, A. (2022).

Measuring and clustering network attackers using

medium-interaction honeypots. pages 294–306.

Storkey, A. (2009). When training and test sets are dif-

ferent: characterizing learning transfer, dataset shift.

Machine Learning, 30(1):3–28.

Xiong, W., Legrand, E.,

˚

Aberg, O., and Lagerstr

¨

om, R.

(2022). Cyber security threat modeling based on the

mitre enterprise att&ck matrix. Software and Systems

Modeling, 21(1):157–177.

Kex-Filtering: A Proactive Approach to Filtering

535