The Game of One More Idea: Gamification of Managerial Group

Decision-Making in Software Engineering

Hannes Salin

a

School of Information and Engineering, Dalarna University, Borl

¨

ange, Sweden

Keywords:

Gamification, Managerial Decision-Making, Group Decisions, Software Engineering, Game Design.

Abstract:

Gamification is widely used and explored for improving learning and increase motivation. However, it has

not been further explored in the context of software engineering managerial decision making, as a supportive

tool in engaging both the individual and the team when making managerial group decisions. By applying a

framework for game- and study design, we develop a card-based game for managerial group decision making,

specifically for software engineering management teams. Our study is an industrial exploratory case study at

the Swedish Transport Administration, where the decision-making game is tested on a management team. The

aim of the study was to evaluate the perceived effects on the team’s engagement and overall decision-making

process. Our experiments showed that the perceived engagement and confidence in making group decisions

using the game was improved. Although difficult to conclude general remarks, the results give indications that

the decision making process could benefit using the card game.

1 INTRODUCTION

Managerial decision-making is a crucial part of any

organization, covering a wide range of decisions from

daily operational tasks to strategic decisions that can

make long-term impact. In the field of software

engineering (SE), making these decisions becomes

even more complex. Depending on the organizational

structure, engineering managers not only have to lead

their teams but also be part of important technology

choices, security strategies, development methodolo-

gies; being technical as a manager is expected and

also proven to be a success factor (Kalliamvakou

et al., 2019). Moreover, soft skills such as team col-

laboration and communication is also highly impor-

tant to consider (Galster et al., 2022). Combining

these required soft and technical skills with the com-

plex landscape of decisions to be made, SE managers

would benefit by using supportive tools or decision

frameworks that support their decision making.

Although not typically used in the context of pro-

viding decision-making support, gamification could

potentially be used for putting more focus on a task

(Pedreira et al., 2015). Gamification refers to using

game-like elements in non-game situations to make

tasks more engaging and effective (Deterding et al.,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6327-3565

2011). It is extensively applied to induce behavioral

changes across individual, cultural, and social con-

texts (AlMarshedi et al., 2017). The methodology is

in particular used for increasing motivation and ef-

ficiency in learning, e.g., within the e-learning con-

text (Khaldi et al., 2023), but also in improved knowl-

edge creation (Elidjen et al., 2022). Further, in Khaldi

et al., (2023) it was also concluded that gamification

as analyzed from a general management perspective

implies that it incorporates fun, engagement, learn-

ing, and data-driven decision-making. Hence, the

methodology have the potential to increase the en-

gagement and efficiency in the managerial context.

However, contrasting results are also found where

managerial gamification has indicated demotivation

and less performance (Liu and Wang, 2020). There-

fore, with unclear results in how this methodology can

impact group decisions, we consider yet one more di-

mension: the software engineering manager context.

Thus, given the decision making complexity for the

SE manager, introducing gamification into manage-

rial decision-making could therefore be explored if

better and more efficient decision making is possible.

By better we primarily refer to the notion of reflexive

as coined by Alvesson et al., namely to think criti-

cally about one’s actions and decisions, and the un-

derlying assumptions that provide guidance (Alves-

son et al., 2016). This is not equivalent to simply re-

Salin, H.

The Game of One More Idea: Gamification of Managerial Group Decision-Making in Software Engineering.

DOI: 10.5220/0012845400003753

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Software Technologies (ICSOFT 2024), pages 59-66

ISBN: 978-989-758-706-1; ISSN: 2184-2833

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

59

flect on one’s decision and the potential outcomes, but

also think critically about the options and what leads

to one’s conclusions. We use this notion and apply it

to managerial group decision making, as the ability to

be more reflexive within a management team, hence

implying a more dynamic group reflective process.

This paper provides preliminary experiment-

based research using a developed prototype card

game, supporting managerial decision making. The

primary aim of the game is decision support to SE

management teams, where managers collaborate in

a wide range of decisions. By adding a gamifica-

tion element into such management team, we perform

experiments in how the chosen game could improve

the ability to increase the individual engagement of a

manager, and how the perceived improvement of man-

agerial group decision making is affected. Our study

consists of a case study of a managerial SE team in

one of the larger Swedish public sector agencies.

The rest of the paper is outlined as follows: the re-

maining of this section includes related work and our

formulated research questions. Section 2 describes

out chosen research methodology, experiment design,

the game development process and output, and a de-

scription of the target company of the case study. Sec-

tion 3 summarizes the result from the experiment, sec-

tion 4 the discussion and analysis of the results, and

we conclude the paper in section 5.

1.1 Related Work

In general, the idea of utilizing gamification in a man-

agement context is not new; a comprehensive sys-

tematic review in the field categorizes several differ-

ent areas within the managerial context and proposes

a framework for analyzing them separately (Wanick

and Bui, 2019). However, none of the categories

identified were specifically within managerial deci-

sion making in the SE context. Moreover, a case

study in managerial decision making was conducted

(Cechella et al., 2021), but within the banking con-

text. Gamification in the SE context is also heavily

studied, several literature reviews have classified dif-

ferent use case areas and frameworks, e.g., (Barreto

and Franc¸a, 2021; Pedreira et al., 2015; de Paula Porto

et al., 2021). However, the primary focus is on the

software engineer-, developer- and architecture roles

and not managerial decision making.

Using card based games for decision making has

been tested in other contexts than SE, e.g., in mili-

tary decision making (Medhurst et al., 2009). Exper-

iments were conducted where cards revealing pieces

of information was used and presented sequentially.

Players was then using the cards to assess different

scenarios for deciding if escalation was needed or

not. Another context investigated, however not us-

ing cards, is in water governance; it was found that

the creation of game-based methods that facilitate

participatory decision-making is also shaped by the

broader principles of group decision making (Aubert

et al., 2019). These findings along with (Aubert et al.,

2022), (Zhou, 2014) and (Schriek et al., 2016) sug-

gests that gamifying decision making does provide

benefits, however not fully evaluated within the con-

text of SE managerial decision making.

1.2 Research Questions

Since the current literature on gamification in the SE

context does not include managerial decision-making

explicitly, in particular engineering manager group

decisions, we address the following research ques-

tions:

• RQ1: Can card-based gamification improve the

perceived quality of SE group managerial deci-

sion making?

• RQ2: Can card-based gamification increase the

individual engagement in SE group managerial

decision making?

2 METHOD

The chosen method is an exploratory case study since

we seek to find preliminary insights of what gamifica-

tion in the managerial decision making within the SE

context can bring forward; hence we are not evaluat-

ing a theory. This approach is suggested by Yin (Yin,

2009) and further elaborated in (Bell et al., 2022).

The case study is over a selected group of managers

at the target company, and thus isolated in their con-

text and working environment. Data collection and

analysis is conducted using a mixed-method approach

(Bell et al., 2022) where quantitative data is collected

using anonymous survey sheets, and qualitative data

is collected via free text surveys and semi-structured

interviews (Bell et al., 2022).

2.1 Gamification Design

As a foundation, we based the construction of our

game using the framework proposed in (Aubert et al.,

2019) and further tested and adapted in (Aubert et al.,

2022). In essence it provides a procedure where the

game construction is build upon the “what, why, who,

when and where” questions, leading to a game-based

approach, specifically the game’s context. The ”why”

ICSOFT 2024 - 19th International Conference on Software Technologies

60

question focuses on the aims and results of the game,

while the ”who” question mainly considers the indi-

viduals involved and their processes. The ”where and

when” questions delve into the situation’s context,

shaping the design encapsulated in the ”how” ques-

tion. This framework thus enables one to design the

most effective game-based approach in order to reach

the targeted outcomes of the gamification, but also

be able to assess it adequately (Aubert et al., 2019).

Hence, the questions provide the context which leads

to defining the game and what type of study is needed

for the assessment.

As noted in (Aubert et al., 2022) we also con-

sider the challenge of individualism vs. collectivism,

namely to balance the competitive factor such that de-

cisions made are not solely driven by individual agen-

das, but instead towards team achievement. Using

the gameficiation ontology proposed in (Garc

´

ıa et al.,

2017) we outline our game-based approach using the

framework from Aubert et al. as follows:

• What. Managerial group decision making

within the SE context, specifically decisions

relating to technology adoption/investment, re-

organizational matters, tools and software devel-

opment strategies etc. Since the organization con-

sists of several SE units, the management team

needs to collectively make such strategic deci-

sions and then implement them throughout the or-

ganization’s different hierarchies.

• Why. The main purpose of the game is to in-

crease the individual engagement in the group de-

cision making process, and to enable the group

to be more reflexive (Alvesson et al., 2016) in a

more structured way. Namely, enable the group

to be more engaged and at the same time thinking

more critically and aiming for data-driven deci-

sions. The goal is to contribute with as many in-

puts and ideas as possible to drive the reflexivity

forward.

• Who. The players are engineering managers, re-

sponsible for the software development teams and

operations. The management team lead, the head

of the department, is also part of the game, acting

as the entity allowed to make any final decisions

when there is no consensus in the group.

• When. The game should be played any time

there is a group decision to be made, and typi-

cally during the normal management team meet-

ings that occur weekly. Moreover, free form meet-

ings with no agendas also occur weekly with the

goal of catching new or un-planned events; these

meetings can also be used if group decisions are

needed on an ad-hoc basis. However, temporal

contraints are needed, e.g., time-boxing so that

decision are not stalled.

• Where. The game is suited for co-located teams,

however future research should implement and

evaluate digitized versions of the game to under-

stand effects in distributed teams.

The details of the development of the game rules

and structure is described in subsequent sections.

2.2 Development of the Game

2.2.1 Planning Poker

The game was developed with inspiration from the

classic planning poker card game used in agile sprint

planning (Grenning, 2002). Although planning poker

does not have a gamification parameter (no player

can really win against the others), it provides other

effects such as reducing optimism bias (Mahni

ˇ

c and

Hovelja, 2012). Moreover, as summarized by Mah-

nic and Hovelja (2012) planning poker builds upon

the Delphi method which is a structured communi-

cation technique that uses rounds of anonymous sur-

veys to collect data from experts on a subject, aiming

for consensus or insightful predictions on complex is-

sues. However, in planning poker there is no elements

of anonymization. Our proposed game uses the same

foundational structure as in planning poker by allow-

ing all players contribute with their perspective (al-

lowed to play cards that indicate an idea, perspective

or opinion). Another structure is that each round en-

forces a group discussion aiming to reach consensus

or majority after a number of iterations of gameplay.

2.2.2 Card Game Design

The competitive element in our game is based on the

idea of using cards, having in mind that the game

should be possible to digitize if needed, e.g., for dis-

tributed teams; some research indicates that specif-

ically trading card game design fulfills this transi-

tion if needed (Marchetti and Valente, 2015). Now, a

competitive game aiming for collective decision mak-

ing should avoid promoting a single solution in it-

self, but instead allowing participants to freely share

their thoughts or providing them with an overview of

various potential compromises (Aubert et al., 2022).

Hence, our construction emphasises this concept by

adding a rule of being able to express either ideas by

playing idea cards, or express the need for more dis-

cussion by playing brainstorming cards. These two

rules will allow the players to be able to share opin-

ions in a structured way, and ensure more time if nec-

essary. To balance the players’ freedom, an overall

The Game of One More Idea: Gamification of Managerial Group Decision-Making in Software Engineering

61

What?

Why?

Who?

When?

Where?

Game design

Planning poker

Exploratory case study

Study design

Aubert et al. framework

denes

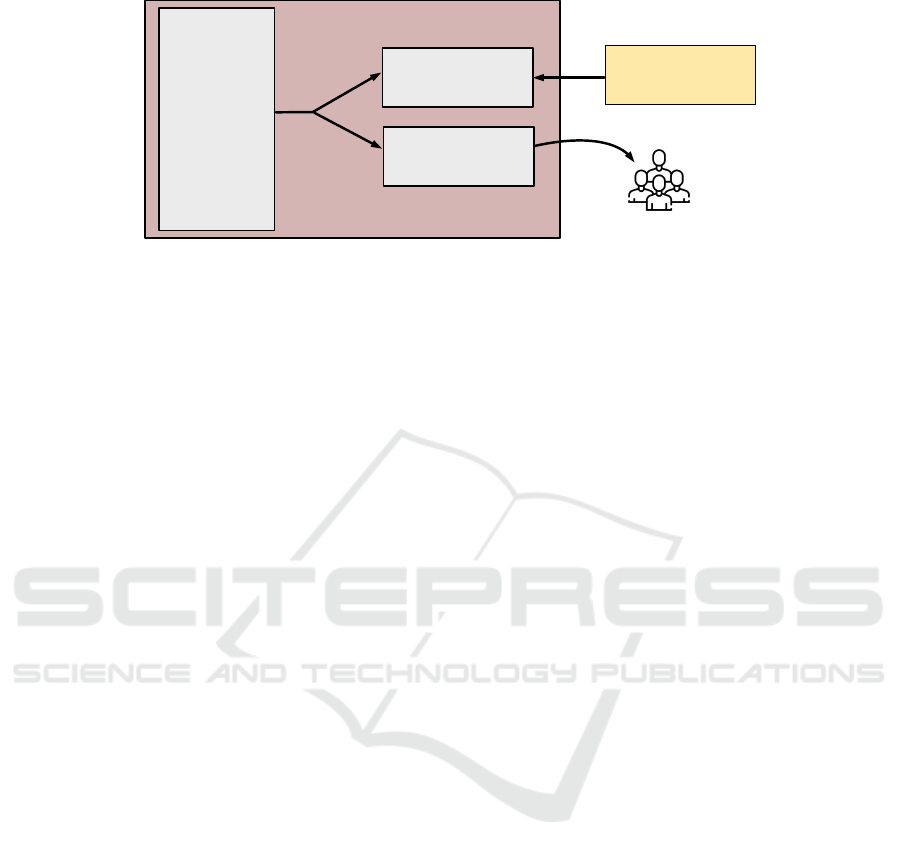

Figure 1: The overall methodology, where the framework by Aubert et al., (2022) is the foundation and planning poker

inspired the game structure. The game was evaluated in an exploratory case study with a selected SE management team.

game master is needed, whom is able to have the fi-

nal saying in situations where players get stuck or no

majority/consensus is reached. Finally, the gamifica-

tion element is of collecting points by achievement,

where each player is rewarded a point (or token) for

every new idea that is presented in the discussion of

a problem/decision. This will enforce creativity and

engagement.

The cards were designed in Affinity Designer and

all graphics were generated using DALL-E (OpenAI,

2021). When generating the card pictures (figures and

symbols), a gender diversity perspective was consid-

ered to spread to occurrence of female and male de-

pictions evenly. A simplified overview of the chosen

methodology is depicted in Fig. 1.

2.2.3 Rules of the Game

In the proposed game, each manager is equipped with

a deck of cards at the beginning of each (weekly)

management meeting. The deck includes the cards

”Low Risk,” ”Medium Risk,” ”High Risk,”, ”I Agree,”

”I Disagree,” a variety of ”Let’s Brainstorm” cards,

”Coffee Break”, ”Parking Lot”, ”Final Decision,” and

”Idea” cards. When a decision is needed and the dis-

cussion starts, the gameplay starts. One player is cho-

sen as the game master (GM) (who has the highest

mandate to make decisions). The game is divided

into two phases: discussion and decision, where for

former is iterative and the latter is the step where the

final decision is made. We outline the two phases as

follows:

• Discussion Phase: the team time boxes the dis-

cussion into 10 minute blocks. During a block the

team discusses the matter and each player may

play an idea card if an idea for solution, a new

perspective or a question that follows by a new

collective insight is given. After the 10-minute

block ends the team goes round the table and

play one risk card each to indicate the individual

perception of risk involved in the current status

of their decision making process. After all risk

cards are played, another round the table is run

where everyone has the opportunity to play a cof-

fee break card indicating the need for a pause, a

final decision card indicating the need for making

a decision now without having more blocks, or a

brainstorming card indicating the need for at least

one more round of discussion. The GM either de-

cides to continue the discussion and thus accept-

ing any brainstorming cards played or switch the

game into the decision phase. If there is diversity

in the perceived risk, i.e., many players have very

different opinions on what risk level the matter has

(from the first round the table), the GM can decide

to run another block regardless of the outcome

of the second round the table. Before the block

ends, each player gets a token or point for every

idea card they played during the block. At any

time during the discussion, any player can play

the parking lot card indicating that the current dis-

cussion has deviated and should be ”parked” for

later. Similarly, the agree- and disagree cards can

be played at any time to indicate a player’s opin-

ion towards an idea, risk opinion or other situa-

tion.

• Decision Phase: If the team reaches a state where

a final decision is needed to be made, the deci-

sion phase starts. Everyone count the number

of tokens or points collected from the previous

phase. At this stage there should be at least one

proposed decision. The GM makes the final deci-

sion and if that turns out to be a previously played

idea from any of the players, that player receives

one more token. The game ends by that deci-

sion and the player with the most number of to-

kens wins. Preferably, the tokens should be saved

and collected incrementally every time the game

is played. Thus, the team can have monthly or an-

ICSOFT 2024 - 19th International Conference on Software Technologies

62

nually milestones rewarding creative and engag-

ing individuals.

COFFEE BREAK

HIGH RISK

Figure 2: Example card design, a coffee break card and high

risk card. All graphics are prompted in DALL-E.

To summarize: players play idea cards to present

new suggestions and other cards to express their opin-

ions on the discussions. The game progresses with

players contributing ideas and reactions, culminating

when the final decision card is played, otherwise di-

versity in perceived risk or the collective need for

further brainstorming, drives the game into another

iteration. The player who has used the most num-

ber of idea cards by this point wins, emphasizing ac-

tive engagement but also rewarding creativity in the

decision-making process.

2.3 Experiment Design

The experiment is constructed by a series of game-

plays, where each play was not determined before-

hand but instead used on any current decision to be

made in the management group. The head of the team

was GM in all instances. For each gameplay a tem-

plate of data was filled by the GM with the purpose to

provide data for the experiment, e.g., gameplay time,

number of iterations and so forth. All gameplays were

scheduled to occur at the standard team meetings in

Q1 2024.

After each game all participants will be asked to

fill an anonymous survey (pen and paper), indicating

the perceived effect of the game in the decision mak-

ing. Three questions were formulated where the an-

swer scale was i Likert scale from 1 to 5 defined as

follows: 1 = worse compared to not using the game,

2 = slightly worse compared to not using the game,

3 = indifferent, 4 = slightly better compared to not

using the game, 5 = better compared to not using the

game. The survey questions were:

• Q1: How was the decision making process (dis-

cussion) compared to not using the game?

• Q2: How confident were you in the final decision?

• Q3: How engaging were you during the decision

making process (discussion)?

Each participant will also be asked to fill a free

text entry of feedback of the game. After the game-

play phase of the experiment, a series of short semi-

structured interviews was planned with two of the par-

ticipants. The interview scheme was based on the fol-

lowing interview questions:

• IQ1: What effects did you experience in the group

decision making when using the game?

• IQ2: Did you have opportunities to challenge

other people’s perspective and be challenged

yourself during the gameplay?

• IQ3: What were the main benefits and drawbacks

of using the game?

• IQ4: Any suggestions for improvements of the

game design, rules, or applicability?

The main aim of the experiment is two-folded: to

capture the experience of using the game as in per-

ceived support (or no support) when making a group

decision, and to capture the level of increased, de-

creased or non-influenced engagement in the manage-

rial group decision (on an individual level). By using

Q3 with IQ1 and IQ2 we would get indications on

the reflexive dimension, i.e., if the player is pushed

towards thinking over the options with engagement,

and possibly showing increase of creativity. The score

cards will indicate these perceptions, however with

the risk of bias and non-statistically significance due

to the small sample size. Since this case study ex-

periment is more of finding indications in a selected

case study, this experiment could be up-scaled in fu-

ture studies with both control groups and larger sam-

ple size (multiple management teams). Therefore, we

limit this particular experiment run in the context of

the target company.

2.4 Target Group Description

We performed the experiment on a software engineer-

ing management team at the Swedish Transport Ad-

ministration’s ICT division. The team was selected

due to convenience sampling and the team size was

n = 7 individuals. All engineering managers were

responsible for several software development teams,

and one manager was also responsible for two opera-

tion (DevOps) teams focused on 24/7 operations and

incident management of the organization’s applica-

tions. The age spread was between 38 and 61 years

old, and all team members had previous manager

roles. None of the participants had tried gamification

methods previously and was not aware of the tech-

nique. Typical types, and not exclusively, of group

The Game of One More Idea: Gamification of Managerial Group Decision-Making in Software Engineering

63

decisions the team handled were strategic topics such

as how to manage the growing amount of contractors,

defining team and organizational structures, invest-

ment options such as training or conferences for the

employees and defining key performance indicators.

3 RESULTS

The experiment was run as a gameplay session on-

site at the target company, with 4 gameplays. The

mean values of the survey scoring from the partic-

ipants are shown in Tab. 1. The management team

was running the game on-site at the company, and at

the time the team’s HR partner was also present but

did not participate in the game. A short introduction

of the rules (5 minutes) was given by the GM before

starting the meeting. The gameplays were then run

every time there was a topic of discussion that needed

a decision to be made. The first round was made in

two blocks and finalized after 18 minutes. One de-

cision was made quickly (under 10 min.) and one

decision was postponed to the next meeting due to

time constraints (after 2 blocks the time was running

out). 4 of the players played idea cards, 2 players

played risk cards during the discussion and 2 play-

ers played agree/disagree cards during the discussion.

One player did not play any cards at all in any game-

play. No one asked for clarifications of the rules or

purpose. After each session the survey score cards

were filled in and collected by the GM. The free text

entries was not filled in by any of the players.

Table 1: The resulting mean values ¯x

i

for each survey ques-

tion i, for the gameplays in the experiment. Time refers to

mean gameplay time, and mean number of 10 minute blocks

that was used.

¯x

1

¯x

2

¯x

3

Mean time Mean blocks

4.0 4.0 4.4 15 min. 2

Two interviews were made, each took about 10

minutes and was on-site: one with player A and one

with player B. Player A was interviewed the same day

after the experiment, and player B was interviewed

2 weeks later. Although a limitation of the valid-

ity of the study with only two interviews, it would

indicate some directions on how the game was per-

ceived. For each question-response pair, we denoted

keywords (coding) if the response related to any of

the reflexive dimensions such as reflection, creative,

thinking, challenge etc. Not all keywords were men-

tioned. We summarize the answers in Tab. 2 as rep-

resentative quotes from A and B respectively, where

keywords are in bold.

Table 2: Summary of semi-structured interviews with

player A and B, keywords in bold.

Question Summary

IQ1 (A) Helped in being more creative.

Made it fun.

IQ1 (B) Made me think more.

IQ2 (A) Using the cards was tricky at first

but made me think [reflect] more

about options.

IQ2 (B) Hard to asses, maybe. People

seemed creative.

IQ3 (A) It made the meeting more fun.

”Sexifying” the decision-making

part. Unclear to see if the scoring

part will motivate me. To get more

benefits, the game should be run

continuously so everyone get used

to it.

IQ3 (B) It was easier to visualize our deci-

sion process. For people that usu-

ally does not talk much, maybe this

approach could help. Inspire if you

are not too creative.

IQ4 (A) Maybe have a digital version that

can be shared on a screen.

IQ4 (B) Hard to tell if there could be any im-

provements, I need to play more.

4 DISCUSSION

The results suggest that the game was improving the

individual engagement in the decision making pro-

cess (high mean values of Q1-Q3) and that the in-

terviewees expressed increase in creativity and fun.

These expressed notions could indicate a higher level

of motivation as expected effect from the gamification

method. The reflexive dimension is difficult to cap-

ture, but the mean value of Q3 (level of engagement

in the decision making) was 4.4 and the answers from

IQ1-IQ3 suggests that the players was indeed thinking

more during the game and found it more fun to engage

in the decision making, thus reflecting and weighing

options could partly be factors that are affected. No

feedback was given for the rules or the game design,

therefore we conclude that these factors was not sig-

nificant for this particular experiment. However, on a

large scale study we would expect to find minor ad-

justments on the cards and/or rules.

The mean time of all gameplays (15 min.) can be

considered short, although depending on what deci-

sion is to be made. Only two blocks in general was

ICSOFT 2024 - 19th International Conference on Software Technologies

64

used for the decisions to be made, with the excep-

tion of one decision that was postponed and the game

had to be cancelled due to time constraints. From

this preliminary data we can suspect that the game

could influence the temporal aspect of the team’s de-

cision making. Without the possibility to benchmark

the decision making speed for the examined group

of study, we would still argue that the time boxing

component of the game contributes to the speed of

progress (Muller, 2009).

One player did not play any card at all during the

whole experiment, and the current experiment design

was not suited for capturing that type of factors. In

the context of digital gamification, the level of partic-

ipation can increase (Barata et al., 2013) by applying

gamification methods, but it is uncertain if this would

apply to our case. Thus, the experiment design could

be further developed into capturing the participation

level, e.g., asking questions on confidence and mo-

tivation to be active in the game. Moreover, it was

less focus on trying to win the game according to the

interviews, i.e., no mentioning of score or competi-

tive perspectives. Instead, just playing the game itself

seemed to initiate engagement and creativity. There-

fore, it would be of interest to investigate further if the

competitive component is necessary or if the cards as

such would be enough to trigger the participants in

engaging more into the decision-making process.

We propose that for future work an up-scale of the

experiment should be made, i.e., run the game in mul-

tiple management teams and preferably have one con-

trol group making decisions without the game during

the experiment. Such up-scale study could indicate

more general results, however if it is still within the

frame of a case study we cannot draw any firm gen-

eralized conclusions. Another suggestion is to adapt

the game further with new perspectives used in group

decision making, e.g., adjustment for teams that are in

different maturity stages (one set of rules for a newly

compiled team, and another set of rules for a more

mature but low-performing team, and so on). Finally,

a thorough study of the game’s effects but digitized so

that distributed teams can use it, would be interesting

since nowadays, especially in post-pandemic times,

the likelihood that the management team is co-located

is not as high as before.

4.1 Threats to Validity

The internal validity can be affected by the fact that

the chosen team in the experiment was via conve-

nience sampling, hence there is a risk that the team is

not representative for a typical SE management team.

Moreover, we did not have a control group to compare

the results, however, since we measured the perceived

effects of the game, it would be hard to calculate dif-

ferences against a control group. This would be rele-

vant for further studies in behavioral SE.

The external validity can be challenged in part

when it comes to generalization. The experiments

were run within in a very specific environment (the

target company) and specific group (the management

team). However, the experiment design is simple

and easy to replicate, thus any further studies could

strengthen the results if applied in other environments

and teams. Following the argument by Ghaisas et al.

(Ghaisas et al., 2013) we could expect some general-

ization by similarity. This means that the character-

istics of the case study use case (size or type of or-

ganization, culture, projects) SE management teams

with similar attributes might respond similarly as in

our study. Hence, while our study does not offer a

complete generalization, it provide insights that could

be relevant in similar settings.

5 CONCLUSIONS

These preliminary results indicate that the game in-

deed improved the selected group’s (perceived) de-

cision making according to the survey and interview

responses. Therefore, we have provided an answer

to RQ1, but with the reservation that further studies

(e.g., longitudinal case studies) are needed for under-

standing underlying factors to the results and improve

the statistical significance. The individual engage-

ment was also increased by using the game in the de-

cision making, the results from Q3 alone strongly in-

dicate this (mean value of 4.4 of 5). Therefore, RQ2

is answered, however we have not provided evidence

that the SE context has any influence. We can there-

fore not conclude if the increased engagement has any

relation to the SE management context or manage-

ment contexts in general. Overall, the game of one

more idea seems to indicate benefits to managerial de-

cision making.

The game is available for free on GitHub:

https://github.com/hannessalin/research-

code/tree/main/decision-card-game with cards

and game rules for printing.

REFERENCES

AlMarshedi, A., Wanick, V., Wills, G. B., and Ranchhod, A.

(2017). Gamification and behaviour. Gamification:

Using game elements in serious contexts, pages 19–

29.

The Game of One More Idea: Gamification of Managerial Group Decision-Making in Software Engineering

65

Alvesson, M., Blom, M., and Sveningsson, S. (2016). Re-

flexive leadership: Organising in an imperfect world.

Sage.

Aubert, A. H., McConville, J., Schmid, S., and Lienert, J.

(2022). Gamifying and evaluating problem structur-

ing: A card game workshop for generating decision

objectives. EURO Journal on Decision Processes,

10:100021.

Aubert, A. H., Medema, W., and Wals, A. E. (2019). To-

wards a framework for designing and assessing game-

based approaches for sustainable water governance.

Water, 11(4):869.

Barata, G., Gama, S., Jorge, J., and Gonc¸alves, D. (2013).

Improving participation and learning with gamifica-

tion. In Proceedings of the First International Confer-

ence on gameful design, research, and applications,

pages 10–17.

Barreto, C. F. and Franc¸a, C. (2021). Gamification in

software engineering: A literature review. In 2021

IEEE/ACM 13th International Workshop on Cooper-

ative and Human Aspects of Software Engineering

(CHASE), pages 105–108.

Bell, E., Bryman, A., and Harley, B. (2022). Business re-

search methods. Oxford university press.

Cechella, F., Abbad, G., and Wagner, R. (2021). Leverag-

ing learning with gamification: An experimental case

study with bank managers. Computers in Human Be-

havior Reports, 3:100044.

de Paula Porto, D., de Jesus, G. M., Ferrari, F. C., and Fab-

bri, S. C. P. F. (2021). Initiatives and challenges of

using gamification in software engineering: A sys-

tematic mapping. Journal of Systems and Software,

173:110870.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. (2011).

From game design elements to gamefulness: defin-

ing ”gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th Inter-

national Academic MindTrek Conference: Envision-

ing Future Media Environments, MindTrek ’11, page

9–15, New York, NY, USA. Association for Comput-

ing Machinery.

Elidjen, Hidayat, D., and Abdurachman, E. (2022).

The roles of gamification, knowledge creation,

and entrepreneurial orientation towards firm perfor-

mance. International Journal of Innovation Studies,

6(4):229–237.

Galster, M., Mitrovic, A., Malinen, S., and Holland, J.

(2022). What soft skills does the software industry

*really* want? an exploratory study of software po-

sitions in new zealand. In Proceedings of the 16th

ACM / IEEE International Symposium on Empirical

Software Engineering and Measurement, ESEM ’22,

page 272–282, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Garc

´

ıa, F., Pedreira, O., Piattini, M., Cerdeira-Pena, A., and

Penabad, M. (2017). A framework for gamification

in software engineering. Journal of Systems and Soft-

ware, 132:21–40.

Ghaisas, S., Rose, P., Daneva, M., Sikkel, K., and Wieringa,

R. J. (2013). Generalizing by similarity: Lessons

learnt from industrial case studies. In 2013 1st Inter-

national Workshop on Conducting Empirical Studies

in Industry (CESI), pages 37–42.

Grenning, J. (2002). Planning poker or how to avoid

analysis paralysis while release planning. Hawthorn

Woods: Renaissance Software Consulting, 3:22–23.

Kalliamvakou, E., Bird, C., Zimmermann, T., Begel, A.,

DeLine, R., and German, D. M. (2019). What makes

a great manager of software engineers? IEEE Trans-

actions on Software Engineering, 45(1):87–106.

Khaldi, A., Bouzidi, R., and Nader, F. (2023). Gamification

of e-learning in higher education: a systematic litera-

ture review. Smart Learning Environments, 10(1):10.

Liu, B. and Wang, J. (2020). Demon or angel: an explo-

ration of gamification in management. Nankai Busi-

ness Review International, 11(3):317–343.

Mahni

ˇ

c, V. and Hovelja, T. (2012). On using planning poker

for estimating user stories. Journal of Systems and

Software, 85(9):2086–2095.

Marchetti, E. and Valente, A. (2015). Learning via game

design: From digital to card games and back again.

Electronic Journal of E-learning, 13(3):pp167–180.

Medhurst, J., Stanton, I., Bird, H., and Berry, A. (2009).

The value of information to decision makers: an ex-

perimental approach using card-based decision gam-

ing. Journal of the Operational Research Society,

60(6):747–757.

Muller, G. (2009). System and context modeling—the role

of time-boxing and multi-view iteration. In Systems

Research Forum, volume 3, pages 139–152. World

Scientific.

OpenAI (2021). DALL-E: Creating Images from Text. http

s://openai.com/research/dall-e. Accessed: [2024-02-

02].

Pedreira, O., Garc

´

ıa, F., Brisaboa, N., and Piattini, M.

(2015). Gamification in software engineering–a sys-

tematic mapping. Information and software technol-

ogy, 57:157–168.

Schriek, C., van der Werf, J. M. E., Tang, A., and Bex,

F. (2016). Software architecture design reasoning: A

card game to help novice designers. In Software Ar-

chitecture: 10th European Conference, ECSA 2016,

Copenhagen, Denmark, November 28–December 2,

2016, Proceedings 10, pages 22–38. Springer.

Wanick, V. and Bui, H. (2019). Gamification in manage-

ment: a systematic review and research directions. In-

ternational Journal of Serious Games, 6(2):57–74.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and meth-

ods, volume 5. sage.

Zhou, Q. (2014). The princess in the castle: Challenging

serious game play for integrated policy analysis and

planning.

ICSOFT 2024 - 19th International Conference on Software Technologies

66